Abstract

We expressed a protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in order to evaluate the humoral immune responses to the C-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein 1 of Plasmodium vivax. This protein (Pv20018) had a molecular mass of 18 kDa and was reactive with the sera of individuals with patent vivax malaria on immunoblotting analysis. The levels of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies against Pv20018 were measured in 421 patients with vivax malaria (patient group), 528 healthy individuals from areas of nonendemicity (control group 1), and 470 healthy individuals from areas of endemicity (control group 2), using the indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method. To study the longevity of the antibodies, 20 subjects from the patient group were also tested for the antibody levels once a month for 1 year. When the cutoff values for seropositivity were determined as the mean + 3 × standard deviation of the antibody levels in control group 1, both IgG and IgM antibody levels were negative in 98.5% (465 of 472) of control group 2. The IgG and IgM antibodies were positive in 88.1% (371 of 421) and 94.5% (398 of 421) of the patient group, respectively. The IgM antibody became negative 2 to 4 months after the onset of symptoms, whereas the IgG antibody usually remained positive for more than 5 months. In conclusion, indirect ELISA using Pv20018 expressed in S. cerevisiae may be a useful diagnostic method for vivax malaria.

Malaria is the most prevalent parasitic disease in the world, and Plasmodium vivax is the second most prevalent species causing malaria, with a yearly estimate of 35 million cases worldwide 11. P. vivax exhibits two distinct types of incubation-relapse patterns, that apparently depend upon its geographical origin. The Chesson strain of New Guinea is a good example of the tropical type of pattern, which is characterized by an early attack, a short latent period, and then a relapse. In contrast, the St. Elizabeth strain of the temperate type exhibits an early primary attack, followed by a long latency of 6 to 11 months. It is thereafter succeeded by a series of relapses occurring at short intervals.

Vivax malaria was an endemic disease in the Republic of Korea (ROK) until the 1970s. However, no indigenous malaria had been reported in the ROK since 1984, and the ROK was considered to be free from malaria at that time. It was not until 1993 that the first reemerging vivax malaria developed near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) in a young soldier who apparently had no history of traveling abroad. Since then, the number of malaria cases has increased exponentially year after year in the northwestern part (the northern part of the Kyonggi Province) of the ROK, reaching more than 1,700 cases in 1997 and approximately 4,000 cases in 1998 4, 7, 9, 24. One of the characteristics of Korean vivax malaria is a prolonged incubation period, which lasts up to 1 year, in a large proportion of patients 26.

Among the proteins of the erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium, merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP1) has been the most intensively studied as a potential target for protective immunity. This protein is synthesized as a precursor with a high molecular mass (180 to 230 kDa) during the stage of schizogony, and it is later processed into several of the major merozoite surface proteins 16. During the invasion process, proteolytic cleavage releases most of the molecule from the merozoite surface, and only a 19-kDa fragment of the C-terminal region is carried into the invaded erythrocytes 1, 2. The biological importance of MSP1 for parasite survival remains to be elucidated. However, it has been well established that antibodies which recognize its C-terminal region inhibit merozoite invasion in vitro 5, 6, 25 and confer passive immunity to naïve mice 3. The potential of this molecule for vaccine development has motivated researchers to study the generation of recombinant proteins containing portions of MSP1. Several recombinant proteins based on the MSP1 sequence of different Plasmodium species have been used to immunize rodents and monkeys. Recent studies have demonstrated that such recombinant proteins can elicit a significant protective immune response 22.

There have been relatively few studies done on the immune response to P. vivax infection. The N-terminal region of the MSP1 of P. vivax (PvMSP1) has been expressed in Escherichia coli 8, 21, 23 and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells 13. In a study performed in Brazil, it was reported that the N-terminal region of PvMSP1 was immunogenic. However, 40% of the individuals with patent infection did not have detectable levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) to the recombinant proteins representing the N-terminal region of PvMSP1, even after multiple malaria attacks. The N- and C-terminal regions of PvMSP1 were also expressed as glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins, respectively, and the recombinant proteins were tested in Brazilian patients with vivax malaria 30. The results of this study showed that 51.4% of the patients were seropositive for the recombinant proteins representing the N-terminal regions of the PvMSP1, and 64.1% of the patients were positive for the proteins representing the C-terminal regions of PvMSP1. However, immune responses against the PvMSP1 from P. vivax of the temperate type have not been studied in detail as of yet.

We expressed the C-terminal region of PvMSP1 in S. cerevisiae and measured the IgM levels, as well as the IgG levels against the C-terminal region of PvMSP1, in order to study the humoral immune response to PvMSP1. We also determined the longevity of the immune response to PvMSP1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

In order to study the sensitivity and specificity of the antibody test, healthy individuals from areas of nonendemicity (control group 1), healthy individuals from areas of endemicity (control group 2), and vivax malaria patients (patient group) were enrolled in this study. Individuals in control group 1 were recruited from a group of healthy soldiers serving at Daejeon City or Choongcheong Province, where malaria does not occur. Control group 1 consisted of 528 subjects. Blood samples from these soldiers were collected in late July when the incidence of malaria reaches its peak level in the ROK. Individuals in control group 2 were recruited from a group of soldiers serving near the DMZ, where malaria is endemic. Those who had a history of malaria were excluded. Control group 2 consisted of 472 subjects, and blood samples were also collected in July. All of the subjects in the controls groups were male and between the ages of 20 and 25.

The patient group included 421 soldiers who were admitted to military hospitals because of patent malaria between May 1998 and October 1999. All of these patients were also male and between 20 and 25 years of age. All were admitted from 1 to 7 days after the onset of symptoms. Two-thirds were admitted within 3 days of the onset of symptoms (mean, 3.1 days). Blood samples were taken before the administration of antimalarial drugs.

To determine the longevity of the antibody response, 20 soldiers from the patient group were tested once a month for up to 1 year after treatment. Two subjects from the patient group were admitted due to recurring malaria, one subject at 8 months after the primary infection and the other subject at 3 months after the primary infection. Blood from these patients was also collected every month for 1 year after treatment of the recurrent malaria.

All the blood samples used in this study were collected after verbal consent and voluntary agreement in writing.

Diagnosis of P. vivax malaria.

The diagnoses of vivax malaria were made by microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears stained with Giemsa staining. To uncover individuals with asymptomatic parasitemia among control groups 1 and 2, vivax malaria parasites were detected using a nested-PCR amplification 27.

Construction of expression vector pYLJ-MSP.

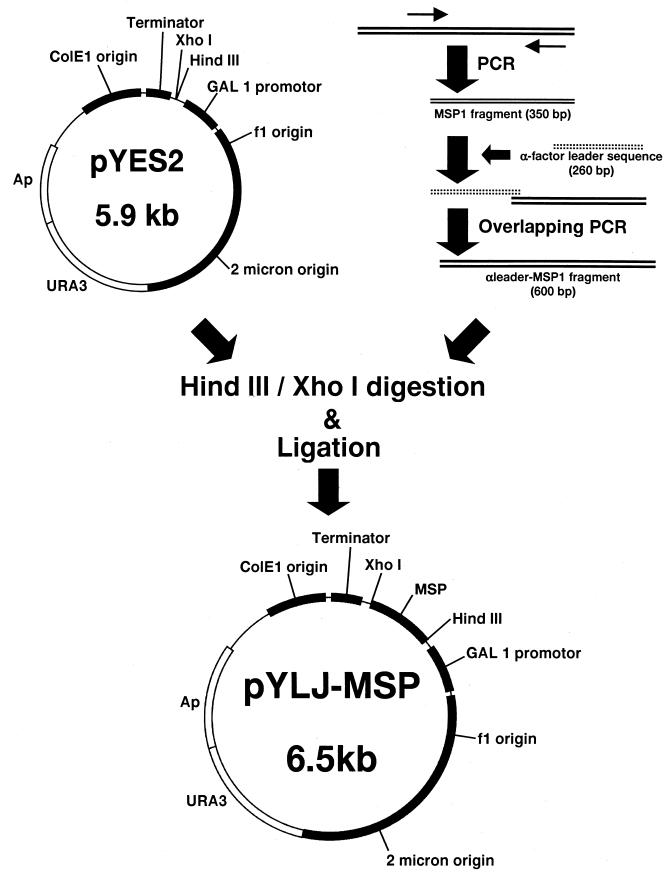

The construction of the pYLJ-MSP is shown schematically in Fig. 1. Genomic malaria DNA was prepared from the blood of a patient with Korean vivax malaria. The patient was a soldier serving at Yeoncheon (the northern part of the Kyonggi Province), which has been one of the most prevalent areas for vivax malaria, in the summer of 1998. Using genomic malaria DNA from the patient as a template, the DNA sequence encoding amino acids Asn1622-Ser1729 was amplified by PCR. The first PCR was done using primers 1 and 3, and the second PCR was done using primers 2 and 3 (Table 1). After initial denaturation (30 s at 94°C), 36 cycles of amplification (94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s) were performed. To create pBC-Pv200-ct657, the amplified DNA was ligated into an EcoRV-digested pBluescript KS(+) vector.

FIG. 1.

Construction of pYLJ-MSP. Two amplified DNAs of P. vivax and the alpha-factor leader sequence were linked by overlapping PCR. The alpha leader-MSP1 and pYES2 were digested with HindIII and XhoI and ligated to create pYLJ-MSP.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers for construction of pYLJ-MSP

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5′-AAA AAA GTC GAC GCC AAA AAG GCC GAG CTG G-3′ |

| 2 | 5′-AAA AAA GTC GAC GAG AAG TAC CTC CCG TTC C-3′ |

| 3 | 5′-AAA AAA ATC GAT TTA AAG CTC CAT GCA CAG G-3′ |

| 4 | 5′-TCT CTA GAT AAG AGAa AAC GAG TCC AAG GAA-3′ |

| 5 | 5′-AAA CTC GAGb TCAc GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG GTGd GCT ACA GAA AAC TCC-3′ |

| 6 | 5′-AAA AAG CTT ATG AGA TTT CCT TCA-3′ |

| 7 | 5′-TCT CTT ATC TAG AGA TAC CC-3′ |

The 3′ terminal sequence of alpha-Factor leader is underlined.

XhoI.

Stop codon.

His tag sequence.

pBC-Pv200-ct657 was amplified using PCR with primers 4 and 5 under the same conditions mentioned above. Alpha interferon-pLBC, including the yeast alpha leader sequence (S. cerevisiae containing alpha interferon-pLBC, available from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures; accession number KCTC0051BP), was amplified with primers 6 and 7 under the same PCR conditions. To create alpha-Pv200-19, the two amplified DNAs were linked with primers 6 and 5 by overlapping PCR under the same PCR conditions. pYES-2 vector and alpha-Pv200-19 were ligated to create pYLJ-MSP after digestion with HindIII and XhoI. pYLJ-MSP was transformed into the S. cerevisiae strain INVSC1. The transformants were propagated and induced as previously described 15.

Expression of the C-terminal region of PvMSP1 in S. cerevisiae.

The expression of the pYLJ-MSP as a secreted product from S. cerevisiae has been described in detail in a previous study 18. The pYLJ-MSP, with a six-histidine residue at the C-terminal end, was purified from culture supernatant by adsorption onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) column and subsequently eluted with a phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The eluted products were concentrated and purified again using Sephacryl S-200 (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) gel filtration chromatography. They were then used as the antigen for indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The final products were confirmed by Western blotting and amino acid sequence analysis.

Indirect ELISA.

Serum from each individual was tested for reactivity with the PvMSP1 recombinant proteins by indirect ELISA as described in several previous studies 19, 21, 31. In brief, each well of a 96-well enzyme immunoassay-radioimmunoassay plate (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) was coated with 50 ng of affinity-purified recombinant proteins diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), incubated overnight at 4°C, and then washed three times with PBS-Tween. The plates were blocked at 37°C for 1 h with 5% normal goat serum (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in PBS-Tween Serum samples were added to duplicate wells at a 1:200 dilution. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, unbound material was washed away, and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG or IgM (Sigma), diluted to 1:40,000, was added to each well. After another hour of incubation at 37°C, the excess labeled antibody was washed away, and a reaction was developed using the o-phenylene diamine (Sigma) substrate system. The plates were read at 490 nm on a Titertek Multiskan Plus MK II ELISA reader (Labsystems, Lugano, Switzerland).

All optical densities at 490 nm (OD490 values) represented the binding of either IgG or IgM to the recombinant protein after subtraction of the binding values of the same serum to PBS alone. Each serum was tested in duplicate, and the OD490 values were averaged. To overcome the differences between plates, all OD490 values were converted into correction values. The serum of the soldier from the patient group who had one of the highest values of IgG and IgM was selected and added to duplicate wells of all of the tested plates as a positive control. The average OD490 of the positive control was converted into 2, and the average OD490 values of all of the tested samples were calculated as follows: [(average OD490 of tested sample − average OD490 of PBS only) × 2]/(average OD490 of positive control − average OD490 of PBS only).

RESULTS

Detection of P. vivax parasites by nested PCR.

P. vivax parasites were detected in all of the soldiers in the patient group by nested PCR before the treatment, but were not detected in any of the soldiers in control group 1. Among 472 whole blood samples from control group 2 collected at the area of endemicity, P. vivax parasites were detected in two soldiers by nested PCR. These soldiers had no clinical signs or symptoms of malaria at the time of our sampling.

Recombinant proteins expressing the C-terminal regions of PvMSP1.

The carboxy-terminal 18-kDa region of Pv200 contains two epidermal growth factor-like domains. The recombinant protein encoding amino acids of this region, Asn1622-Ser1729, were expressed. Coomassie-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels showed that this recombinant protein had a molecular weight of 18 kDa and that the protein was reactive with the serum of individuals with patent malaria on Western blot analysis (data not shown).

Anti-Pv20018 antibody levels in the malaria-naïve control groups and P. vivax malaria patients.

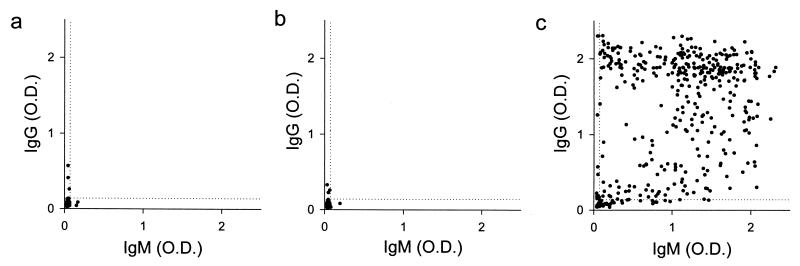

The anti-Pv20018 antibody levels are shown in Fig. 2. In control group 1, the mean value and standard deviation (SD) of the IgG levels were 0.053 and 0.029, respectively, and those of the IgM levels were 0.040 and 0.010, respectively. In control group 2, the mean value and SD of the IgG levels were 0.050 and 0.027, respectively, and those of the IgM levels were 0.039 and 0.010, respectively. In the patient group, the mean value and SD of the IgG levels were 1.31 and 0.75, respectively, and those of the IgM levels were 1.03 and 0.62, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Anti-Pv20018 antibody levels of individuals in each group. Results are shown for control group 1 (528 healthy, malaria-naïve soldiers working in areas of nonendemicity) (a), control group (470 healthy, malaria-naïve soldiers working in areas of endemicity) (b), and the patient group (421 soldiers with patent malaria infection) (c). The horizontal dotted line and the vertical dotted line represent the cutoff values for seropositivity. The cutoff values were determined as mean + 3 × SD of the antibody levels in control group 1 (i.e., corrected OD490 = 0.14 for IgG and corrected OD490 = 0.07 for IgM).

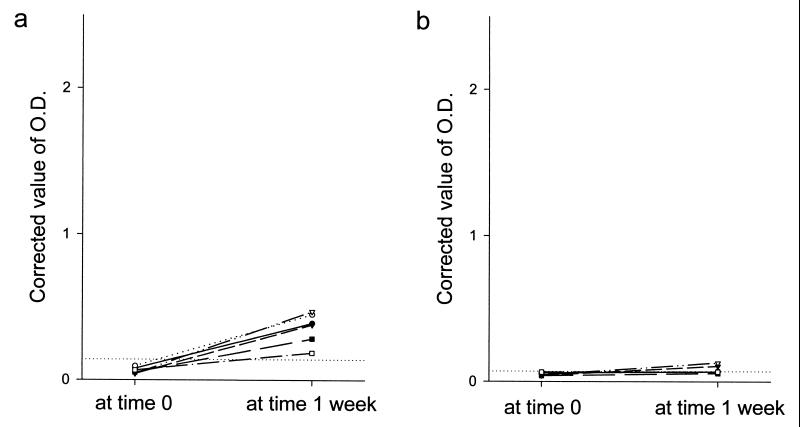

When the cutoff values for seropositivity were determined as mean + 3 × SD of the antibody levels in control group 1 (i.e., 0.14 for IgG and 0.07 for IgM), both IgG and IgM antibody levels were below the cutoff values in 98.5% (465 of 472) of control group 2. The IgG and IgM antibody levels were positive in 88.1% (371 of 421) and 94.5% (398 of 421) of the patient group, respectively. Both IgG and IgM antibody levels were below the cutoff values in 12 subjects from the patient group. Six of these subjects were retested 1 week after the first test, and their antibody levels had converted to seropositive. However, in all six of these subjects the levels of IgG antibody were below 0.48, and their IgM antibody levels were below 0.13 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Seroconversion of the antibody levels of six patients who were seronegative at the first blood collection. These patients were tested again one week after the first test, and their IgG antibody levels had converted to seropositive (a). However, their IgM levels were below 0.13 at the second test (b). The horizontal dotted lines represent the cutoff values of IgG (corrected OD490 = 0.14) and IgM (corrected OD490 = 0.07), respectively.

In the two patients with recurrent malaria, the IgG levels were both 2.30. This was the second highest value in the patient group. Their IgM levels were 0.06 and 0.045, respectively.

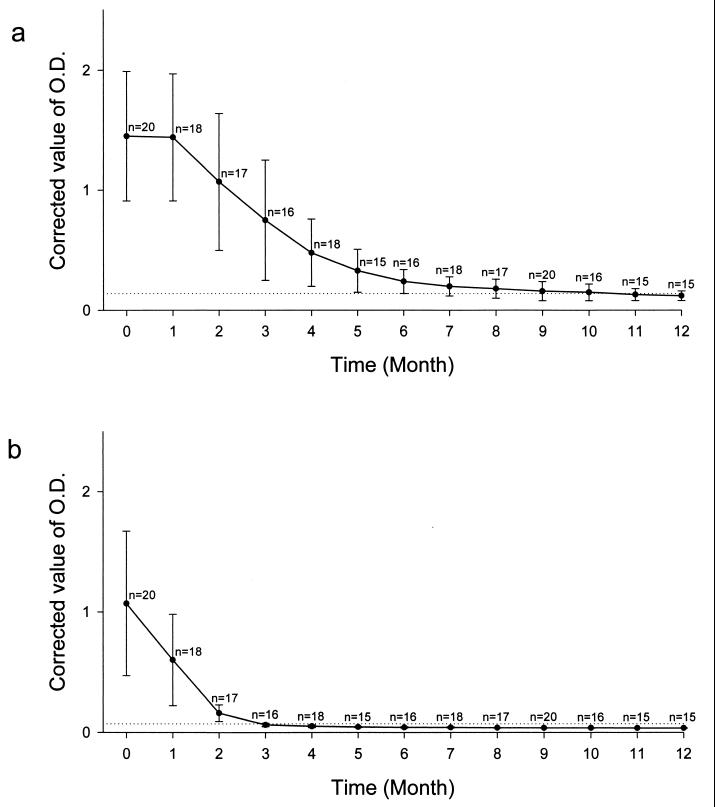

Longevity of anti-Pv200 antibody responses.

The mean value of the IgG levels of 20 tested patients had decreased to near the cutoff value by 10 months after the treatment (Fig. 4a). Antibody levels of IgG started to be converted to seronegative in 4 patients 6 months after the treatment, and the total number of seronegatives increased to 6 patients 7 months after the treatment, and to 11 patients 10 months after the treatment. However, the IgG levels of 6 of the patients did not convert to seronegative until 1 year after the treatment.

FIG. 4.

Changes in the mean values of anti-Pv20018 antibody levels in 20 patients with vivax malaria. The horizontal dotted lines represent the cutoff values of IgG (corrected OD490 = 0.14) and IgM (corrected OD490 = 0.07), respectively. (a) Change in the mean value of IgG; (b) change in the mean value of IgM. n denotes the number of patients tested at each time point. Error bars, SD.

The mean value of the IgM levels of these patients decreased below the cutoff value 3 months after the treatment (Fig. 4b). The IgM levels were seropositive in only 2 out of 18 patients 4 months after treatment. The IgM levels had converted to seronegative in these 20 patients by 5 months after the treatment.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we expressed the C-terminal region of the PvMSP1 and evaluated the humoral immune response to this antigen by indirect ELISA. Recombinant Pv20018 had a molecular mass of 18 kDa, and it had the same amino acid sequence as the Sal-I strain in this region 13. Out of the various antigens to P. vivax, the antibody response against the circumsporozoite protein has been the most intensively studied. Previous studies have demonstrated that the levels and frequency of antibodies against the circumsporozoite protein were higher in individuals in areas of endemicity than in those in areas of nonendemicity 28, 31. However, the circumsporozoite protein has been found to have low immunogenicity 17, and more than 20% of the patients in one study did not have detectable antibody levels against circumsporozoite protein at the early stages of symptom development 10.

One previous study demonstrated that PvMSP1 is expressed on the surface of almost all parasites in the erythrocytic stage 16. The mean parasite count in Korean vivax malaria patients with patent malaria infection has been measured at approximately 5,000/μl 14. This results in sufficient immune recruitment by PvMSP1 in individuals with patent malaria infection. Therefore, we chose PvMSP1 instead of the circumsporozoite as our candidate antigen for the serodiagnosis of patent malaria infection.

In this study, the sensitivity of the test for IgG against PvMSP was higher (88.1%) than in previous studies, which have reported sensitivity levels of 50 to 60% 29, 30. The major difference between our study and the previous ones is the system employed for the expression of PvMSP1. Yeast cells were used for the expression system in our study, whereas an E. coli system was employed in the previous studies. Glycosylation processes, which play an important role in creating the three-dimensional conformation of glycoproteins, do not occur in E. coli cells. However, they do occur effectively in yeast cells 12. Because PvMSP1 is a glycoprotein, the yeast expression system may be more effective in mimicking PvMSP1 than the E. coli expression system. This difference may explain the improved sensitivity in our study.

When mean + 2 × SD of the antibody levels in control group 1 was regarded as the cutoff value for positive reactions (i.e., 0.11 for IgG and 0.06 for IgM), the sensitivity of the test was 97.9% (412 of 421), and the specificity was 96.4% (455 of 472) in control group 2. When mean + 3 × SD of the antibody levels in control group 1 was regarded as the cutoff value for positive reactions (0.14 for IgG and 0.07 for IgM), the sensitivity of the test was 97.1% (409 of 421), and the specificity was 98.5% (465 of 472) in control groups 2. Therefore, we chose mean + 3 × SD of the antibody levels in control group 1 as the cutoff value for seropositivity.

Of the 472 healthy soldiers in the areas of endemicity, two (0.4%) had asymptomatic parasitemia, which was detected by PCR. Anti-Pv200 antibody levels were significantly raised in both of them (i.e., IgG of 1.2 and 0.8, and IgM of 0.8 and 0.9, respectively).

In this study, the levels and frequency of antibodies against PvMSP1 were similar in the malaria-naïve individuals in the areas of nonendemicity to those in the areas of endemicity. In contrast, it has been reported that the levels and frequency of antibodies against the circumsporozoite protein were higher in malaria-naïve individuals in areas of endemicity than in malaria-naïve individuals in areas of nonendemicity 28, 31. These findings suggest that PvMSP1 may not be a useful antigen in detecting individuals who have been infected with sporozoites but have not yet passed into the erythrocytic stage. In order to detect these individuals, the antigenicity must come into being during the prehepatic stage and must be maintained into the erythrocytic stage. However, PvMSP1 is expressed only during the erythrocytic stage 20, and thus the specific immune response was not available to differentiate the individuals in the areas of endemicity from those in the areas of nonendemicity.

Of note is the fact that the IgG antibody was positive as early as 3 days after the onset of symptoms. In many infectious diseases, it can take 2 to 4 weeks before the seroconversion of the IgG antibody occurs. This strongly suggests that patients have parasitemia long before they develop symptoms. Indeed, the period of asymptomatic parasitemia (prepatent parasitemia plus patent parasitemia) of vivax malaria is known to be 6 to 10 days. The six patients in whom IgG levels were seroconverted had very low IgM levels (Fig. 3). Two explanations may be possible for the low IgM levels. Firstly, because of the affinity maturation during the development of IgG, IgG antibody may have higher affinity to the MSP1 antigen than IgM antibody. Secondly, IgG levels as well as IgM levels were low in the six patients, and this suggests that they might be poor responders to the MSP1 antigen.

The longevity of IgG was more than 1 year in one-third of our subjects, and the longevity of IgM was more than 3 months in most of them. Therefore, we suggest that caution be used when interpreting a positive antibody test.

In the ROK, one-third of all blood donors had traditionally been soldiers. However, since the vivax malaria epidemic began, the number of soldiers donating blood has sharply decreased, because more than half of all of the vivax malaria cases occur in soldiers. A microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears is the standard procedure for the diagnosis of malaria. However, microscopic examination is highly time-consuming and labor-intensive. Therefore, it is not a practical method for mass testing, such as screening donated blood. For this purpose, antibody testing using an immunoassay may be a more useful and efficient method.

In conclusion, PvMSP1 is an adequate antigen for the serodiagnosis of patent malaria infection, since sufficient amounts of antibody are induced in almost all individuals with patent malaria infection at an early stage of symptom development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the soldiers of the ROK Army who voluntarily participated in this study and their medical and executive officers. We also thank Young-Hoon Kim for his critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a Korean Military Medical Association grant for the fiscal year 1999 and by a grant (03-99-022) from the Seoul National University Hospital Research Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackman M J, Heidrich H G, Donachie S, McBridge J S, Holder A A. A single fragment of a malaria merozoite surface protein remains on the parasite during red blood cell invasion and is the target of invasion-inhibiting antibodies. J Exp Med. 1990;172:379–382. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackman M J, Ling I T, Nicholls S C, Holder A A. Proteolytic processing of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 produces a membrane-bound fragment containing two epidermal growth factor-like domains. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90127-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns J M, Parke L A, Daly T M, Cavacini L A, Weidanz W P, Long C A. A protective monoclonal antibody recognizes a variant-specific epitope in the precursor of the major merozoite surface antigen of the rodent malarial parasite Plasmodium yoelii. J Immunol. 1989;142:2835–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai I H, Lim G I, Yoon S N, Oh W I, Kim S J, Chai J Y. Occurrence of tertian malaria in a male patient who has never been abroad. Korean J Parasitol. 1994;32:195–200. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1994.32.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang S P, Gibson H L, Lee N C, Barr P J, Hui G S. A carboxyl-terminal fragment of Plasmodium falciparum gp 195 expressed by a recombinant baculovirus induces antibodies that completely inhibit parasite growth. J Immunol. 1992;149:548–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chappel J A, Holder A A. Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit Plasmodium falciparum invasion in vitro recognize the first growth factor-like domain of merozoite surface protein-1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;60:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90141-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho S Y, Kong Y, Park S M, Lee J S, Lim Y A, Chae S L, Kho W G, Lee J S, Shim J C, Shin H K. Two vivax malaria cases detected in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1994;32:281–284. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1994.32.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Portillo H A, Levitus G, Camargo L M A, Ferreira M U, Mertens F. Human IgG responses against the N-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein 1 of Plasmodium vivax. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87(Suppl. III):77–84. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761992000700010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feighner B H, Park S I, Novakoski W L, Kelsey L L, Strickman D. Reemergence of Plasmodium vivax malaria in the Republic of Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:295–297. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke E D, Lucas C M, Chauca G, Wirtz R A, Hinostroza S. Antibody response to the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium vivax in naturally infected humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46:320–326. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.46.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galinski M R, Barnwell J W. Plasmodium vivax: merozoites, invasion of reticulocytes, and considerations for malaria vaccine development. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:20–29. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)80641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gemmill T R, Trimble R B. Overview of N- and O-linked oligosaccharide structures found in various yeast species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1426:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson H L, Tucker J E, Kaslow D C, Krettli A U, Collins W E, Kiefer M C, Bathurst I C, Barr P J. Structure and expression of the gene for Pv200, a major blood-stage surface antigen of Plasmodium vivax. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:325–334. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90230-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hale T R, Halpenny G W. Malaria in Korean veterans. Can M A J. 1953;68:444–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinnen A, Hicks J B, Fink G R. Transformation of yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:1929–1933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.4.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holder A A. The precursor to major merozoite surface antigens: structure and role in immunity. Prog Allergy. 1988;41:72–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones T R, Yuan L F, Marwoto H A, Gordon D M, Wirtz R A, Hoffman S L. Low immunogenicity of a Plasmodium vivax circumsporozoite protein epitope bound by a protective monoclonal antibody. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:837–843. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaslow D C, Hui G S N, Kumar S. Expression and antigenicity of Plasmodium falciparum major merozoite surface protein (MSP119) variants secreted from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;63:283–289. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaslow D C, Kumar S. Expression and immunogenicity of the C-terminal of a major blood-stage surface protein of Plasmodium vivax, Pv20019, secreted from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Immunology Lett. 1996;51:187–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemp D J, Coppel R L, Anders R F. Repetitive proteins and genes of malaria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:181–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levitus G, Mertens F, Speranca M A, Camargo L M A, Ferreira M U, del Portillo H A. Characterization of naturally acquired human IgG responses against the N-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein 1 of Plasmodium vivax. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:68–76. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto S, Yukitake H, Kanbara H, Yamada T. Long-lasting protective immunity against rodent malaria parasite infection at the blood stage by recombinant BCG secreting merozoite surface protein-1. Vaccine. 1999;18:832–834. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mertens F, Levitus G, Ferreira M U, Camargo L M A, Dutra A P, del Portillo H A. Longitudinal study of naturally acquired humoral immune responses against the merozoite surface protein 1 of Plasmodium vivax in patients from Rondonia, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:383–392. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paik Y H, Ree H I, Shim J C. Malaria in Korea. Jpn J Exp Med. 1988;58:55–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirson P J, Perkins M E. Characterization with monoclonal antibodies of a surface antigen of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. J Immunol. 1985;134:1946–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shute P G, Lupascu G, Branzei P, Maryon M, Constantinescu P, Bruce-Chwatt L J, Draper C C, Killick-Kendrick R, Garnham P C. A strain of Plasmodium vivax characterized by prolonged incubation: the effect of numbers of sporozoites on the length of the prepatent period. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1977;70:474–481. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(76)90132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu X P, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario V E, Thaithong S, Brown K N. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snow R W, Shenton F C, Lindsay S W, Greenwood B M. Sporozoites, antibodies, and malaria in children in a rural area of The Gambia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1989;83:559–568. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1989.11812388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soares I S, da Cunha M G, Silva M N, Souza J M, del Portillo H A, Rodrigues M M. Longevity of naturally acquired antibody responses to the N- and C-terminal regions of Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 1. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:357–363. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soares I S, Levitus G, Souza J M, der Portillo H A, Rodrigues M M. Acquired immune responses to the N- and C-terminal regions of Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 1 in individuals exposed to malaria. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1606–1614. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1606-1614.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wirtz R A, Rosenberg R, Sattabongkot J, Webster H K. Prevalence of antibody to heterologous circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium vivax in Thailand. Lancet. 1990;336:593–595. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]