ABSTRACT

Each prokaryotic domain, Bacteria and Archaea, contains a large and diverse group of organisms characterized by their ultrasmall cell size and symbiotic lifestyles (potentially commensal, mutualistic, and parasitic relationships), namely, Candidatus Patescibacteria (also known as the Candidate Phyla Radiation/CPR superphylum) and DPANN archaea, respectively. Cultivation-based approaches have revealed that Ca. Patescibacteria and DPANN symbiotically interact with bacterial and archaeal partners and hosts, respectively, but that cross-domain symbiosis and parasitism have never been observed. By amending wastewater treatment sludge samples with methanogenic archaea, we observed increased abundances of Ca. Patescibacteria (Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738) and, using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), discovered that nearly all of the Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 cells were attached to Methanothrix (95.7 ± 2.1%) and that none of the cells were attached to other lineages, implying high host dependency and specificity. Methanothrix filaments (multicellular) with Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 attached had significantly more cells with no or low detectable ribosomal activity (based on FISH fluorescence) and often showed deformations at the sites of attachment (based on transmission electron microscopy), suggesting that the interaction is parasitic. Metagenome-assisted metabolic reconstruction showed that Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 lacks most of the biosynthetic pathways necessary for cell growth and universally conserves three unique gene arrays that contain multiple genes with signal peptides in the metagenome-assembled genomes of the Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 lineage. The results shed light on a novel cross-domain symbiosis and inspire potential strategies for culturing CPR and DPANN.

KEYWORDS: Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR), Candidatus Patescibacteria, Archaea, Candidatus Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738, symbiosis, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), shotgun metagenomic analysis

OBSERVATION

One major lineage of the domain Bacteria, Candidatus Patescibacteria (also known as the Candidate Phyla Radiation/CPR superphylum) (1, 2), is a highly diverse group of bacteria that widely inhabits natural (3, 4) and artificial ecosystems (5–7) and is characterized by its small cell and genome sizes (8) and by its poor (genomically predicted) abilities to synthesize cellular building blocks (4), which is suggestive of a symbiotic dependency for cell growth. Most members remain uncultured, leaving major knowledge gaps in the range and nature of their symbioses (i.e., commensal, mutualistic, and parasitic relationships) (3), although a few cultivation-based and microscopy-based studies have demonstrated host-specific symbiotic and parasitic interactions between Ca. Patescibacteria and other bacteria; e.g., Ca. Saccharimonadia with Actinomycetota (formerly known as Actinobacteria) (9) and Ca. Gracilibacteria with Gammaproteobacteria (10, 11). This suggested a specialization toward bacteria-bacteria symbioses, especially given the parallels with DPANN, an archaeal analog which has only been observed to interact with other archaea (4, 12); however, one study has reported symbiosis between Ca. Patescibacteria and eukarya (13), indicating that the Ca. Patescibacteria host range reaches beyond bacteria. Here, based on our previous observations of predominant Ca. Patescibacteria members and methanogenic archaea (“methanogens”) (6, 7), we hypothesize that some Ca. Patescibacteria may symbiotically interact with archaea and use exogenous archaea to culture potential archaea-dependent Ca. Patescibacteria.

To create conditions conducive to the growth of archaea-dependent Ca. Patescibacteria, we took a strategy similar to that of virus or phage cultivation, in which exogenous methanogenic archaea were grown in the presence of Ca. Patescibacteria that would presumably grow using molecules derived from these active hosts (i.e., through symbiosis and parasitism). We chose acetate-utilizing methanogens as the partners, as they ubiquitously inhabit methanogenic ecosystems (5, 6, 14), form symbiotic interactions with bacteria (14), utilize an energy source (acetate) that is generally noninhibitory to organotrophs (unlike other methanogen substrates, such as H2 or formate [15]), and conveniently have a highly distinguishable cell morphology/structure that is easily differentiable from those of other organisms (i.e., easily traceable under a microscope). To culture Ca. Patescibacteria that may interact with archaea, we used microbial community samples from a bioreactor (“sludge”) that was particularly abundant in Ca. Patescibacteria (7) as starting material and amended them with acetate-utilizing methanogens (Methanothrix soehngenii GP6 and Methanosarcina barkeri MS) as symbiotic partners and acetate as an energy source for the archaea (Text S1). Potential growth factors (yeast extract, various amino acids, and nucleoside monophosphates) were also provided, as Ca. Patescibacteria are known to have poor biosynthetic capacities (4).

The file containing materials and methods. Download Text S1, PDF file, 0.2 MB (172.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

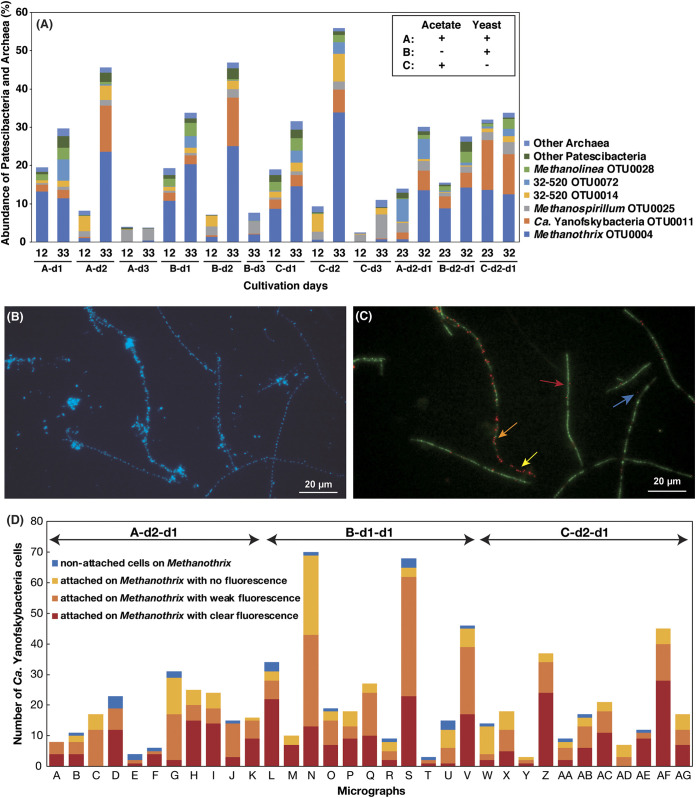

In the cultivation experiments, we performed serial dilutions (10−1, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−6, defined as d1–d4) of the sludge-methanogen mixture to help eliminate low-abundance bacteria that may have interfered with the Ca. Patescibacteria growth. In some cultures with confirmed gas production, we detected the enrichment (increased relative abundances up to 12.1% in A-d2 on day 33) of a population of an uncultured clade of Ca. Patescibacteria, namely, Ca. Yanofskybacteria OTU0011, which belongs to class Ca. Paceibacteria (formerly known as Parcubacteria/OD1 [1]) (Fig. 1A), and we also observed many small cells (<1 μm in diameter) that were consistently attached to cells with a morphology characteristic of Methanothrix (long rods of approximately 0.8 μm in diameter with blunt ends strung together, forming multicellular filaments), with the number of attached cells increasing as the culture aged (Fig. S1A and S1B). To further eliminate other nontarget populations in the culture (i.e., “enrich” the target organisms), we subcultured those abundant in small cells and microscopically confirmed the continued physical attachment of small cells with Methanothrix-like cells (Fig. S1C and S1D). Three independent subcultures (defined as A-d2-d1, B-d1-d1, and C-d2-d1) retaining Ca. Yanofskybacteria (each amended with acetate and/or yeast extract) with high abundance (1.7 to 13.1%) (Fig. 1A) were used for further microscopy observation.

FIG 1.

(A) Relative abundance of predominant Candidatus Patescibacteria and Archaea in the culture systems based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. Micrographs of (B) 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride staining and (C) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) obtained from culture system B-d1-d1 on day 23 as well as the (D) counted numbers of Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells in 33 micrographs. (C) The microorganisms in the panel were labeled with Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe (red) and Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe (green). Blue, yellow, orange, and red arrows in (C) indicate nonattached Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells on Methanothrix, attached on Methanothrix with no fluorescence, attached on Methanothrix with weak fluorescence, and attached on Methanothrix with clear fluorescence, respectively, and these colors are consistent with those in the bar diagrams of (D). Culture systems were amended with (A) acetate and yeast extract, (B) yeast extract, and (C) acetate for carbon sources. A-d2-d1, B-d1-d1, and C-d2-d1 were subcultures transferred from A-d2, B-d1, and C-d2, respectively.

Phase-contrast micrographs of (A–D) the small cells attached on Methanothrix-like cells in culture systems A-d2 on day 33 (A and B) and C-d2-d1 on day 23 (C and D). Yellow squares indicate high magnification parts of (A) and (B). White arrows indicate the colorless cells of the Methanothrix-like structure. Download FIG S1, JPG file, 1.2 MB (1.2MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Through fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), which allowed for the differentiation of target populations with fluorescence microscopy, we successfully verified that the small cells attached to the surfaces of the Methanothrix filaments were indeed Ca. Yanofskybacteria (with probes MX825 and Pac_683, respectively) (Fig. 1B and C; also see Fig. S2–S4). Across all subcultures, most Methanothrix filaments (59.3 ± 5.3%) were physically associated with Ca. Yanofskybacteria, and, more importantly, nearly all of the Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells (95.7 ± 2.1%) were attached to Methanothrix filaments, with none attached to other hosts and only a small fraction remaining (4.2 ± 2.1%) unattached, showing that the physical attachment and symbiosis are Methanothrix-specific (Fig. 1D).

Micrographs of (A and E) phase-contrast, (B and F) 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride staining, and (C, D, G, and F) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) obtained from culture system A-d2-d1 on day 23. (C and G) The Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe and (D and H) the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe. Blue, yellow, orange, and red arrows indicate nonattached Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells on Methanothrix, attached on Methanothrix with no fluorescence, attached on Methanothrix with weak fluorescence, and attached on Methanothrix with clear fluorescence, respectively, and these colors are consistent with those in the bar diagrams in Fig. 1D. Download FIG S2, JPG file, 1.7 MB (1.8MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

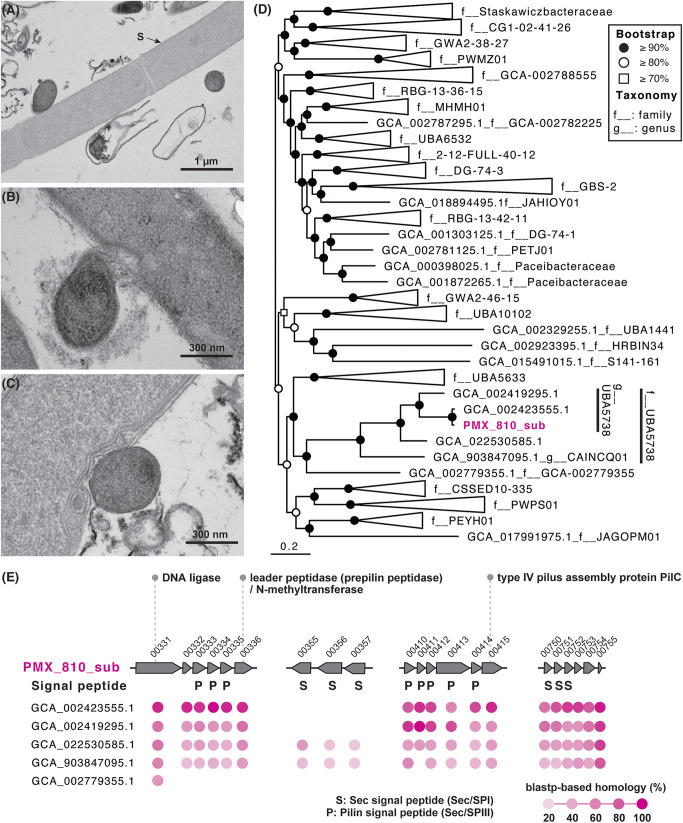

Compared to the Methanothrix filaments that were free of ectosymbionts in the cultures, those physically associated with more than 5 Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells contained significantly larger areas (P < 0.05 for all cultures) with low ribosomal activity (based on FISH fluorescence) (Fig. S5). Moreover, a major fraction of the Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells (18.8 ± 1.9%) were associated with these low-activity Methanothrix cells. Though highly qualitative, many of the Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells (39.6 ± 6.1%) were attached to Methanothrix cells with weak fluorescence (e.g., Fig. S2H, S3H, and S4H), which may reflect the negative influence of attachment. Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), we further observed that Methanothrix (sheathed filamentous cells) (16, 17) often had deformed cell walls where submicron coccoid-like cells (presumably Ca. Yanofskybacteria; 0.46 ± 0.13 μm long and 0.36 ± 0.07 μm wide, 0.0377 ± 0.0200 μm3 calculated cell volumes) were attached (Fig. 2A–C). The clearly negative influence of Ca. Yanofskybacteria implies that the symbiosis between Ca. Yanofskybacteria and Methanothrix is parasitic.

FIG 2.

(A–C) Transmission electron micrographs of small coccoid-like submicron cells attached on the Methanothrix-like cells in culture system A-d2 on day 40. S indicates sheath structures of the Methanothrix-like cells. (D) Phylogenetic tree of order Ca. Paceibacterales based on concatenated phylogenetic marker genes of GTDBtk 2.0.0 (ver. r207). The phylogenetic position of the metagenomic bin PMX_810_sub is shown in pink color. (E) Gene arrays containing multiple genes with signal peptides in Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 and the family level uncultured lineage GCA-002779355. P and S indicate the sec signal peptide and the pilin signal peptide, respectively. The pink colored circles indicate a BLASTP-based homology (threshold of ≤ 1e−10) with metagenomic bin PMX_810_sub. No annotated genes are hypothetical proteins (based on the annotation using BlastKOALA in Table S3). Abbreviated locus tags are shown in (E) (e.g., “PMX_810_sub_00331” as “00331” in the row of PMX_810_sub).

Micrographs of (A and E) phase-contrast, (B and F) 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride staining, (C, D, G, and F) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) obtained from culture system B-d1-d1 on day 23. (C and G) The Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe and (D and H) the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe. Blue, yellow, orange, and red arrows indicate nonattached Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells on Methanothrix, cells attached on Methanothrix with no fluorescence, cells attached on Methanothrix with weak fluorescence, and cells attached on Methanothrix with clear fluorescence, respectively, and these colors are consistent with those in the bar diagrams in Fig. 1D. Download FIG S3, JPG file, 2.0 MB (2.1MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Micrographs of (A and E) phase-contrast, (B and F) 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride staining, (C, D, G, and F) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) obtained from culture system C-d2-d1 on day 23. (C and G) The Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe and (D and H) the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe. White arrows indicate Methanothrix-cells without Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells. Blue, yellow, orange, and red arrows indicate nonattached Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells on Methanothrix, cells attached on Methanothrix with no fluorescence, cells attached on Methanothrix with weak fluorescence, and cells attached on Methanothrix with clear fluorescence, respectively, and these colors are consistent with those in the bar diagrams in Fig. 1D. Download FIG S4, JPG file, 1.9 MB (1.9MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Cell length proportions of clear fluorescence of Methanothrix filamentous cells calculated based on fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) signals using the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe and the Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe. The Methanothrix cells attached with >5 Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells were chosen for calculation. The statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s t test. Download FIG S5, JPG file, 1.2 MB (1.3MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Through shotgun metagenomic analysis, we successfully recovered a metagenome-assembled genome of Ca. Yanofskybacteria (PMX_810_sub; 0.8 Mb in total) and nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences (Fig. 2D; Fig. S6; Tables S1 and S2). Based on 43 marker genes for Ca. Patescibacteria (1), the completeness and contamination of PMX_810_sub were estimated to be 90.7% and 0%, respectively. Phylogenetic classification based on SILVA v138.1 and GTDB r207 taxonomy confirmed the classification of the Ca. Yanofskybacteria (99.7% similarity with FPLM01004990) (Fig. S6; Table S2) and the Ca. Patescibacteria family UBA5738 of the order Paceibacterales (Fig. 2D; Table S1). The metagenome-assembled genome PMX_810_sub lacks many biosynthetic pathways (e.g., those for the biosynthesis of amino acids and fatty acids) (Table S3), suggestive of a host-dependent or partner-dependent lifestyle, as was also observed for other Ca. Patescibacteria members (4). Previously, gene arrays that contain small signal peptides have been found in pathogenic bacterial genomes and in Ca. Patescibacteria (18), which may be related to their parasitic potential (19). Indeed, all of the metagenome-assembled genomes that were affiliated with Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 contained genes for protein secretion systems (e.g., SecADEFGY) (Table S3) and universally conserved three unique gene arrays that contained multiple genes with signal peptides that could be recognized by the aforementioned systems (and one additional gene array conserved in the two deep-branching genomes) (Fig. 2D and E). Interestingly, all of the genes included in these arrays encode hypothetical proteins, suggesting that, if these genes are involved in interactions with the host, the mechanism is unrelated to known forms of parasitism. Further investigation using transcriptomics and proteomics is necessary to clarify the mechanisms behind the parasitism by this organism and lineage.

Phylogenetic tree of Candidatus Paceibacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. The 16S rRNA gene-based tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method implemented in the ARB program. The operational taxonomic units (OTUs) obtained in this study are shown in bold type in the tree. Sequences that match those of the Pac_683 probe are shown in red font. Download FIG S6, JPG file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of the metagenomic bins from the Candidatus Patescibacteria enrichment cultures observed in this study. Download Table S1, XLSX file, 0.03 MB (33.6KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of the recovered 16S rRNA gene sequences from culture system A-d2-33 using EMIRGE software. Download Table S2, XLSX file, 0.02 MB (17.4KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of the annotation of metagenomic bin PMX_810_sub using DRAM, BlastKOALA, and SignalP annotation software. Download Table S3, XLSX file, 0.2 MB (176.2KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

In total, through the first successful cultivation and enrichment of the Ca. Patescibacteria class Ca. Paceibacteria (to which Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 belongs), we discovered that Ca. Patescibacteria/CPR can symbiotically interact with the domain Archaea. The obtained results suggest that the observed interaction between Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 and Methanothrix is a host-specific parasitism. Although the host range and the preference of Ca. Yanofskybacteria/UBA5738 remain unclear, the observed ability of Ca. Patescibacteria to interact with methanogenic archaea, a central group of organisms in anaerobic ecosystems, warrants further investigation into how parasitism may influence ecology and carbon cycling. As the presented archaea cocultivation strategy was effective in culturing Ca. Patescibacteria that were inhabiting methanogenic environments, we anticipate that the further refinement of cocultivation combined with gene and protein expression will allow for the characterization of the details of the symbiosis between Ca. Patescibacteria and Archaea, the determination of the diversity of archaea-dependent Ca. Patescibacteria, and, ultimately, the elucidation of the influence of these organisms’ interactions on anaerobic ecology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partly supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI JP16H07403 and JP21H01471, a matching fund between the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) and Tohoku University, and by research grants from the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (G-2019-1-052 and G-2022-1-014). We thank Riho Tokizawa, Yuki Ebara, and Tomoya Ikarashi at AIST for their technical assistance.

K. Kuroda and T.N. designed this study. K. Kuroda performed the sampling, cultivation, microscopy, and sequence analysis. K. Kuroda, K.Y., R.N., K. Kubota, M.K.N., and T.N. interpreted the data. K. Kuroda, M.K.N., and T.N. wrote the manuscript with input from all coauthors. All authors have read and approved the manuscript submission.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Kyohei Kuroda, Email: k.kuroda@aist.go.jp.

Masaru K. Nobu, Email: m.nobu@aist.go.jp.

Takashi Narihiro, Email: t.narihiro@aist.go.jp.

Stephen J. Giovannoni, Oregon State University

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown CT, Hug LA, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Castelle CJ, Singh A, Wilkins MJ, Wrighton KC, Williams KH, Banfield JF. 2015. Unusual biology across a group comprising more than 15% of domain Bacteria. Nature 523:208–211. doi: 10.1038/nature14486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Waite DW, Rinke C, Skarshewski A, Chaumeil PA, Hugenholtz P. 2018. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol 36:996–1004. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He C, Keren R, Whittaker ML, Farag IF, Doudna JA, Cate JHD, Banfield JF. 2021. Genome-resolved metagenomics reveals site-specific diversity of episymbiotic CPR bacteria and DPANN archaea in groundwater ecosystems. Nat Microbiol 6:354–365. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00840-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castelle CJ, Brown CT, Anantharaman K, Probst AJ, Huang RH, Banfield JF. 2018. Biosynthetic capacity, metabolic variety and unusual biology in the CPR and DPANN radiations. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:629–645. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mei R, Nobu MK, Narihiro T, Kuroda K, Muñoz Sierra J, Wu Z, Ye L, Lee PKH, Lee P-H, van Lier JB, McInerney MJ, Kamagata Y, Liu W-T. 2017. Operation-driven heterogeneity and overlooked feed-associated populations in global anaerobic digester microbiome. Water Res 124:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narihiro T, Nobu MK, Bocher BTW, Mei R, Liu WT. 2018. Co-occurrence network analysis reveals thermodynamics-driven microbial interactions in methanogenic bioreactors. Environ Microbiol Rep 10:673–685. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuroda K, Narihiro T, Shinshima F, Yoshida M, Yamaguchi H, Kurashita H, Nakahara N, Nobu MK, Noguchi TQP, Yamauchi M, Yamada M. 2022. High-rate cotreatment of purified terephthalate and dimethyl terephthalate manufacturing wastewater by a mesophilic upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor and the microbial ecology relevant to aromatic compound degradation. Water Res 219:118581. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakai R. 2020. Size matters: ultra-small and filterable microorganisms in the environment. Microbes Environ 35. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME20025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He X, McLean JS, Edlund A, Yooseph S, Hall AP, Liu SY, Dorrestein PC, Esquenazi E, Hunter RC, Cheng G, Nelson KE, Lux R, Shi W. 2015. Cultivation of a human-associated TM7 phylotype reveals a reduced genome and epibiotic parasitic lifestyle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:244–249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419038112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yakimov MM, Merkel AY, Gaisin VA, Pilhofer M, Messina E, Hallsworth JE, Klyukina AA, Tikhonova EN, Gorlenko VM. 2022. Cultivation of a vampire: ‘Candidatus Absconditicoccus praedator’. Environ Microbiol 24:30–49. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreira D, Zivanovic Y, López-Archilla AI, Iniesto M, López-García P. 2021. Reductive evolution and unique predatory mode in the CPR bacterium Vampirococcus lugosii. Nat Commun 12:2454. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dombrowski N, Lee J-H, Williams TA, Offre P, Spang A. 2019. Genomic diversity, lifestyles and evolutionary origins of DPANN archaea. FEMS Microbiol Lett 366:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong J, Qing Y, Guo X, Warren A. 2014. “Candidatus Sonnebornia yantaiensis”, a member of candidate division OD1, as intracellular bacteria of the ciliated protist Paramecium bursaria (Ciliophora, Oligohymenophorea). Syst Appl Microbiol 37:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saha S, Basak B, Hwang J-H, Salama E-S, Chatterjee PK, Jeon B-H. 2020. Microbial symbiosis: a network towards biomethanation. Trends Microbiol 28:968–984. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nobu MK, Narihiro T, Mei R, Kamagata Y, Lee PKH, Lee P, McInerney MJ, Liu W. 2020. Catabolism and interactions of uncultured organisms shaped by eco-thermodynamics in methanogenic bioprocesses. Microbiome 8:111. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00885-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Touzel JP, Prensier G, Roustan JL, Thomas I, Dubourguier HC, Albagnac G. 1988. Description of a new strain of Methanothrix soehngenii and rejection of Methanothrix concilii as a synonym of Methanothrix soehngenii. Int J Syst Bacteriol 38:30–36. doi: 10.1099/00207713-38-1-30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dueholm MS, Larsen P, Finster K, Stenvang MR, Christiansen G, Vad BS, Bøggild A, Otzen DE, Nielsen PH. 2015. The tubular sheaths encasing Methanosaeta thermophila filaments are functional amyloids. J Biol Chem 290:20590–20600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.654780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLean JS, Bor B, Kerns KA, Liu Q, To TT, Solden L, Hendrickson EL, Wrighton K, Shi W, He X. 2020. Acquisition and adaptation of ultra-small parasitic reduced genome bacteria to mammalian hosts. Cell Rep 32:107939. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Méheust R, Burstein D, Castelle CJ, Banfield JF. 2019. The distinction of CPR bacteria from other bacteria based on protein family content. Nat Commun 10:4173. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12171-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The file containing materials and methods. Download Text S1, PDF file, 0.2 MB (172.3KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Phase-contrast micrographs of (A–D) the small cells attached on Methanothrix-like cells in culture systems A-d2 on day 33 (A and B) and C-d2-d1 on day 23 (C and D). Yellow squares indicate high magnification parts of (A) and (B). White arrows indicate the colorless cells of the Methanothrix-like structure. Download FIG S1, JPG file, 1.2 MB (1.2MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Micrographs of (A and E) phase-contrast, (B and F) 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride staining, and (C, D, G, and F) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) obtained from culture system A-d2-d1 on day 23. (C and G) The Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe and (D and H) the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe. Blue, yellow, orange, and red arrows indicate nonattached Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells on Methanothrix, attached on Methanothrix with no fluorescence, attached on Methanothrix with weak fluorescence, and attached on Methanothrix with clear fluorescence, respectively, and these colors are consistent with those in the bar diagrams in Fig. 1D. Download FIG S2, JPG file, 1.7 MB (1.8MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Micrographs of (A and E) phase-contrast, (B and F) 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride staining, (C, D, G, and F) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) obtained from culture system B-d1-d1 on day 23. (C and G) The Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe and (D and H) the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe. Blue, yellow, orange, and red arrows indicate nonattached Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells on Methanothrix, cells attached on Methanothrix with no fluorescence, cells attached on Methanothrix with weak fluorescence, and cells attached on Methanothrix with clear fluorescence, respectively, and these colors are consistent with those in the bar diagrams in Fig. 1D. Download FIG S3, JPG file, 2.0 MB (2.1MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Micrographs of (A and E) phase-contrast, (B and F) 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride staining, (C, D, G, and F) fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) obtained from culture system C-d2-d1 on day 23. (C and G) The Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe and (D and H) the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe. White arrows indicate Methanothrix-cells without Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells. Blue, yellow, orange, and red arrows indicate nonattached Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells on Methanothrix, cells attached on Methanothrix with no fluorescence, cells attached on Methanothrix with weak fluorescence, and cells attached on Methanothrix with clear fluorescence, respectively, and these colors are consistent with those in the bar diagrams in Fig. 1D. Download FIG S4, JPG file, 1.9 MB (1.9MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Cell length proportions of clear fluorescence of Methanothrix filamentous cells calculated based on fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) signals using the Methanothrix-targeting MX825-FITC probe and the Ca. Yanofskybacteria-targeting Pac_683-Cy3 probe. The Methanothrix cells attached with >5 Ca. Yanofskybacteria cells were chosen for calculation. The statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s t test. Download FIG S5, JPG file, 1.2 MB (1.3MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Phylogenetic tree of Candidatus Paceibacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. The 16S rRNA gene-based tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method implemented in the ARB program. The operational taxonomic units (OTUs) obtained in this study are shown in bold type in the tree. Sequences that match those of the Pac_683 probe are shown in red font. Download FIG S6, JPG file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, jpg) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of the metagenomic bins from the Candidatus Patescibacteria enrichment cultures observed in this study. Download Table S1, XLSX file, 0.03 MB (33.6KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of the recovered 16S rRNA gene sequences from culture system A-d2-33 using EMIRGE software. Download Table S2, XLSX file, 0.02 MB (17.4KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Summary of the annotation of metagenomic bin PMX_810_sub using DRAM, BlastKOALA, and SignalP annotation software. Download Table S3, XLSX file, 0.2 MB (176.2KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2022 Kuroda et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.