Abstract

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) continues to be a major health problem worldwide, causing considerable morbidity and mortality due to peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. The aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. A PRISMA systematic search appraisal and meta-analysis were conducted. A systematic literature search of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Scopus, and Google Scholar was conducted up to August 2022. Generic, methodological and statistical data were extracted from the eligible studies, which reported the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. A random effect meta-analysis was conducted on crude sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath test rates. Heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran’s Q and I2 tests. The literature search yielded a total of 5267 studies. Of them, 41 articles were included in the final analysis, with a sample size ranging from 50 to 21857. The sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection ranged between 64–100% and 60.5–100%, respectively. The current meta-analysis showed that the sensitivity points of estimate were 92.5% and 87.6%, according to the fixed and random models, respectively. In addition, the specificity points of estimate were 89.9% and 84.8%, according to the fixed and random models, respectively. There was high heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 98.128 and 98.516 for the sensitivity and specificity, respectively, p-value < 0.001). The 13C/14C-urea breath tests are highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, H. pylori, meta-analysis, sensitivity, specificity, urea breath tests

1. Introduction

The spiral-shaped bacteria Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) can be found attached to the stomach’s epithelial lining or in the gastric mucous layer [1]. H. pylori continues to be a serious health issue in the world, contributing significantly to morbidity and mortality from stomach cancer and peptic ulcer disease [2]. More than 90% of duodenal ulcers and up to 80% of stomach ulcers are brought on by H. pylori [3]. Recent research has demonstrated a link between chronic H. pylori infection and the emergence of stomach cancer [4]. Additionally, H. pylori infection affects almost two-thirds of the world’s population [5]. According to earlier estimates, more than 50% of people worldwide have H. pylori in their upper gastrointestinal tracts [6,7], with developing nations having a higher prevalence of this illness. In addition, in countries with poor sanitation, 90% of the adult population can be affected [8].

Most H. pylori-infected people never experience any signs of the infection, whereas H. pylori causes chronic active, chronic persistent, and atrophic gastritis in both adults and children [9]. Furthermore, contamination with H. pylori causes gastric and duodenal ulcers [10]. Additionally, the infection has been linked to the emergence of several malignancies [11]. Comparatively to those who are not infected with H. pylori, infected individuals have a 2- to 6-fold greater risk of developing gastric cancer and mucosal-associated lymphoid-type (MALT) lymphoma [12]. Additionally, extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the listed organs (stomach, esophagus, colon, rectum, or tissues around the eye) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (stomach) lymphoid tissue cancers have also been linked to H. pylori [13,14].

Researchers have hypothesized that H. pylori influences or protects against a variety of different disorders, but many of these connections are still debatable [15]. According to certain research, H. pylori may play a significant part in the natural ecology of the stomach, such as by affecting the types of bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract [16]. Other research points to the potential benefits of non-pathogenic H. pylori strains in normalizing stomach acid output and controlling appetite [17]. People who have active duodenal or gastric ulcers or a known history of ulcers should be tested for H. pylori and should be treated if discovered to be infected. Following resection of early gastric cancer and for low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, screening for and managing H. pylori infection is advised [18].

Invasive and non-invasive testing techniques can also be used to diagnose H. pylori infection [19]. An invasive method to check for H. pylori infection is an endoscopic biopsy. The best way to identify H. pylori infection is to combine a fast urease test or microbial culture with a histological study of two sites following an endoscopic biopsy [20]. The carbon urea breath test, stool antigen testing, and blood antibody tests are a few non-invasive tests for H. pylori infection that may be appropriate [18].

The 13C and 14C tests are two urea breath test (UBTs) that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Both exams are reasonably priced and provide real-time results availability. Although the radiation dose is relatively low (approximately 1 microCi) [21] and the 14C-UBT uses a radioactive isotope, some doctors may prefer the 13C test since it is non-radioactive compared to 14C, especially in young children and pregnant women. 14C-UBT has a high degree of diagnostic accuracy [22].

However, it should be noted that the UBT has occasionally failed to provide an accurate diagnosis because its accuracy has frequently been compared to stomach biopsies, the gold standard, and it is widely recognized that the latter test is prone to sampling error (because of the discontinuous H. pylori colonization of the gastric mucosa). For instance, the low specificity (e.g., high rate of false positives) of the UBT in some of the comparison studies may actually be attributable to the test’s low sensitivity [23]. This has been confirmed by some writers who discovered that numerous UBT results that appeared to be false positives were actually correct results, as was amply demonstrated by the examination of additional multiple biopsy specimens taken from the same patients who underwent a second gastroscopy [24].

To confirm H. pylori colonization and to track its eradication, UBT is advised. A positive UBT results in an active H. pylori infection, necessitating treatment or additional testing using invasive techniques. Initial H. pylori treatment involves either triple, quadruple, or sequential therapy regimens, all of which contain a proton pump inhibitor in addition to a variety of antibiotics; treatment durations typically range from 7 to 14 days [25].

The patient is given either 13C or 14C-labeled urea to drink during this test. Rapid urea metabolization by H. pylori results in absorption of the tagged carbon. If H. pylori is present, the tagged carbon can subsequently be quantified as carbon dioxide in the patient’s exhaled breath [26].

Numerous changes have been suggested since Graham et al.’s initial description of the 13C-UBT to precisely detect H. pylori infection [27]. Changes have been made to the test meal type, the period of breath collection, the cut-off values, and the equipment used to determine isotope enrichment, among other things. A definitive standardization of this test has not yet been established, despite the fact that many variations to the UBT approach have been suggested and a large number of studies pertaining to its methodology have been published. Hence, the current systematic review aims to determine the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PRISMA Guidelines and Protocol Registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis were produced following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Table S1). The study protocol was registered at The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, registration No. CRD42022354308).

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

The author systematically and comprehensively searched English articles published in PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Scopus, and Google Scholar without a region or time limit. To increase the search scale, a combination of search strategies was carried out; First: search MESH (medical subject heading) using the following terms: “13C UBT”, “14C UBT”, and “Helicobacter Pylori Infection” (Table S2); Second free-text search using the following search keywords: “Helicobacter pylori”, “H. pylori”, “Helicobacter infection”, “dyspepsia”, “gastritis”, “urea breath test”, “breath test”, “13C-UBT”, “14C-UBT”, “UBT”, “Sensitivity”, and “Specificity”. Boolean operator (OR) was used to combine synonyms, and (AND) was used to combine the cases with tests.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria (Inclusion/Exclusion)

Articles studied the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. However, articles where the end measure was not the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, review articles, case report articles, non-English language articles, articles lacking pertinent data, and articles without full text, were excluded.

2.4. Study Screening

The EndNote V.X8 software was employed for the article screening process management. The duplicates were omitted, then the author meticulously selected the included articles by screening the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the articles.

2.5. Data Extraction

The required data were extracted in a standardized table that included the following headings: name of the first author and year of publication, country of the study, the population of the study, the sample size of the study, mean age of the study participants, gender of the study participants, study design, name of UBT (13C or 14C), the dose of 13C/14C -urea, using of infrared, the cut-off UBT threshold, the used gold standard for H. pylori detection, the duration from ingestion of carbon isotope to the collection of post-ingestion exhaled air, diagnostic sensitivity percentages, and diagnostic specificity percentages.

2.6. Quality Assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATFQS), established by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) [28], was used to assess the quality of the included studies. Each article underwent eight items of the tool, which were individually scored as “1” denotes strong, “2” denotes moderate, and “3” denotes poor quality. Thereafter, the overall rating for each study was calculated based on the following criteria: “1” denotes strong (no ratings of weak), “2” denotes moderate (one rating of weak), and “3” denotes weak quality (two or more weak ratings) [29].

2.7. Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis was achieved by using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (CMA, version 3, BioStat, Tampa, FL, USA). The Fail-Safe N test was employed to calculate the effect size values of the included studies.

Publication bias was identified by the funnel plot, and Begg’s and Mazumdar’s rank correlation tests were used to detect the potential publication bias among the included articles. Kendall’s tau is used to understand the strength of the relationship between two variables.

The I-squared (I2) statistic was used to measure the heterogeneity between the included articles, and values of 25%, 50%, and 75% are regarded as low, moderate, and high estimations, respectively [30]. A non-significant level of statistical heterogeneity is assumed when the p-value > 0.05. The implementation of a random-effect model was prompted by the substantial level of variability [31].

The Meta-Disc 1.4 software was used in the analysis of the likelihood ratio for positive and negative test (LR+ and LR-), and symmetric receiver operating characteristics (SROC) curve.

3. Results

3.1. Search Findings

A total of 5,267 articles were obtained from the search in the five databases: PubMed (n = 1756), Web of Science (n = 512), EMBASE (n = 187), Scopus (n = 867), and Google Scholar (n = 1945). The remained number of articles after omitting the duplicates was 2377. Then, 1363 and 1015 articles were removed by title and abstract screening, respectively. The full texts of the remained 248 articles were assessed. Finally, 207 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The screening process resulted in 41 articles being accepted for qualitative synthesis and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Articles selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Articles

The majority of the included articles were published in 2003 (six), followed by 2000 (four), 2002 (four), 1998 (two), 2001 (two), 2005 (two), 2007 (two), 2009 (two), 2021 (two), and one for 1989, 1991, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2004, 2008, 2011, 2012, 2015, 2017, 2018, and 2019. The majority of the articles were conducted in China (seven), followed by Japan (three), Taiwan (three), Spain (three), Turkey (three), the United States (two), Italy (two), and one from Germany, Australia, Brazil, Belgium, Poland, Mexico, Estonia, India, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, Israel, South Korea, Indonesia, New Zealand, Singapore, Pakistan, and Austria. The vast majority of the articles were cross-sectional in design. Only one study was performed on children, and the rest recruited adults. The sample size of the articles ranged between 50 and 21857 participants. Out of the 41 included articles, only 12 articles reported the sensitivity and specificity of 14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. Obtained breath samples were analyzed using an isotope-selective, non-dispersive infrared spectrometer in only nine articles. The duration from ingestion of carbon isotope to the collection of post-ingestion exhaled air ranged between 5–30 minutes. The sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection ranged between 64–100% and 60.5–100%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

The extracted data from the included articles.

| The First Author (Year) | Country | Study Population | Sample Size | Mean Age (Year) | Gender (M:F) |

Study Design | Name of UBT (13C/14C) | Dose of 13C/14C-Urea | Infrared Assisted | Cut-Off UBT Threshold | Reference Standard | Time | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyor et al. 1989 [32] | Australia | Patients underwent upper GI endoscopy | 63 | 58.8 | 33:30 | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | NM | Histo and/or culture | Every 5 min for 30 min |

94.0 | 93.0 |

| Marshall et al. 1991 [33] | United States |

Patients underwent gastroscopy with biopsy | 153 | NM | NM | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | >6% | Combined (Culture, RUT and histo) |

30 min after administration |

97.0 | 100.0 |

| Hilker et al. 1996 [34] | Germany | Patients underwent urea breath test and gastroscopy with biopsy | 174 | 46 | 68:106 | Retrospective cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | >250 | Histo | 30 min after administration |

94.6 | 100.0 |

| Allardyce et al. 1997 [35] | New Zealand |

Patients with dyspeptic symptoms | 63 | 56.5 | 37:26 | Cross-sectional | 14C | 37 | No | 82% DPM | Histo or (Biopsy and rapid urea test) |

30 min and 60 min post ingestion |

100.0 | 95.0 |

| Perri et al. 1998 [36] | Belgium | Patients underwent upper GI endoscopy | 172 | 39.7 | 14:158 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | 3.3% | Histo and/or culture | Every 15 min for one h after ingestion of the urea solution |

96.0 | 93.5 |

| Wang et al. 1998 [37] | Taiwan | Patients underwent routine upper GI endoscopy | 152 | NM | NM | Cross-sectional | 13C | 100 mg | No | 2.0 | Histo and/or culture | 30 min after ingestion | 99.0 | 93.0 |

| Van der Hulst et al. 1999 [38] | Italy | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms | 199 | 48 | 105:94 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | Yes | >5% | Histo and culture | 30 min after administration |

96.0 | 97.0 |

| Chen et al. 2000 [39] | Japan | Patients underwent GI endoscopy | 169 | 53.9 | 101:68 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | 2.5% | Combined (Histo and serology) |

20 min after normal respiration |

100.0 | 96.0 |

| Hahn et al. 2000 [40] | United States | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 67 | 58.8 | 61:6 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | >2.3% | Combined (Histo, UBT and serology) |

30 min after administration |

95.0 | 97.0 |

| Riepl et al. 2000 [41] | Austria | Patients underwent gastroscopy with biopsy | 100 | 51.6 | 51:49 | Cross-sectional | 13C | 100 mg | Yes | >4% | Combined three tests (Histo, UAT and culture) |

NM | 92.0 | 94.0 |

| Peng et al. 2000 [42] | China | Patients with gastritis and dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 136 | 47.6 | 66:70 | Prospective cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | 4.8% | Culture or combined (Histo and RUT) |

15 min after ingestion | 93.8 | 89.1 |

| Wong et al. 2000 [43] | China | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 202 | 49 | 90:112 | Cross-sectional | 13C | 75 mg | No | 5.0% | Histo and/or culture | 30 min after ingestion | 96.5 | 97.7 |

| Wong et al. 2001 (a) [44] | China | Patients underwent upper GI endoscopy for the investigation of dyspepsia or for follow-up after H. pylori eradication and/or ulcer healing | 206 | 48.9 | 97:109 | Cross-sectional | 13C | 50 mg | No | 3.0% | Histo and/or culture | 30 min after ingestion | 96.0 | 98.2 |

| Wong et al. 2001 (b) [45] | China | Patients with dyspepsia underwent upper GI endoscopy | 294 | 47.6 | 100:194 | Cross-sectional | 13C | 75 mg | No | 5.0% | Culture or combined (Histo and RUT) |

30 min after ingestion | 92.6 | 96.9 |

| Gomes et al. 2002 [46] | Brazil | Patients underwent GI endoscopy | 137 | 46.7 | 70:67 | Cross-sectional | 14C | 185 | No | 1000–2000 CPM | Combined (Histo and RUT) |

30 min post ingestion |

95.0 | 98.3 |

| Kato et al. 2002 [47] | Japan | Children underwent upper GI endoscopy | 232 | 11.9 | 136:84 | Cross-sectional | 13C | 100 mg | Yes | 3.5% | Combined (Histology and rapid urease) and/or culture |

20 min after ingestion | 97.8 | 98.5 |

| Kopański et al. 2002 [48] | Poland | Patients with chronic gastritis | 92 | 45.5 | 56:36 | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | >5% | Combined (Culture, serology, UBT and urine test for C-urea) |

30 min after administration |

100.0 | 89.5 |

| Chua et al. 2002 [49] | Singapore | Patients underwent esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy | 100 | 45 | 70:30 | Prospective cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | NM | Histo and/or culture | 30 min after ingestion | 94.2 | 100.0 |

| Chen et al. 2003 [50] | Taiwan | Patients underwent upper pan-endoscopy |

586 | 45.7 | 306:280 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | Yes | ≥2% | Culture alone or RUT | 20 min after drinking solution |

97.8 | 96.8 |

| Gatta et al. 2003 [51] | Italy | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms | 200 | 53 | 87:113 | Prospective cross-sectional | 13C | 75 | No | NM | Combined (Histology and rapid urease) and/or culture |

30 min post ingestion |

100.0 | 100.0 |

| Gomollon et al. 2003 [52] | Spain | Patients underwent upper GI endoscopy | 314 | 54.1 | 146:168 | Prospective cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | ≥5% | Culture and/or Combined (Histo and RUT) |

30 min post ingestion |

97.3 | 100.0 |

| Valdepérez et al. 2003 [53] | Spain | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms | 85 | 41.6 | 43:44 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | NM | Histo and RUT | 30 min after administration |

92.0 | 100.0 |

| Wong et al. 2003 [54] | China | Patients underwent upper GI endoscopy | 200 | 48.4 | 87:113 | Cross-sectional | 13C | 100 mg | Yes | 1.2% | Culture or combined (Histo and RUT) |

30 min after ingestion | 100.0 | 98.0 |

| Öztürk et al. 2003 [55] | Turkey | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms | 75 | 41 | 56:19 | Cross-sectional | 14C | 37 | No | 100 DPM | Histology | NM | 81.0 | 75.0 |

| Urita et al. 2004 [56] | Japan | Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 129 | 60.3 | 54:75 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | 2.5% | Combined (Histology and rapid urease) and/or culture |

30 min after ingestion | 97.7 | 94.0 |

| Gurbuz et al. 2005 [57] | Turkey | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 65 | 42.4 | 22:46 | Cross-sectional | 14C | 37 | No | >50 CPM | Combined tests (Histo and RUT) |

10 min after drinking solution |

89.7 | 77.8 |

| Peng et al. 2005 [58] | China | Patients underwent routine upper GI endoscopy | 100 | 51.5 | 57:43 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | 5% | Culture or combined (Histo and RUT) |

30 min after ingestion | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Ortiz-Olvera et al. 2007 [59] | Mexico | Patients underwent gastroscopy with biopsy | 88 | 45 | 49:39 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | >4.22% | Culture and/or combined (Histo and RUT) |

30 min after administration |

90.2 | 93.3 |

| Rasool et al. 2007 [60] | Pakistan | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 94 | 40.8 | 60:34 | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | >50 CPM | Two reference tests. Patient did both separately: (1) Histo; (2) RUT |

After 10 min | 92.0 | 93.0 |

| Özdemir et al. 2008 [61] | Turkey | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 89 | 45 | 30:59 | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | 25 < CPM as Heliprobe |

Combined; any 2 positive (RUT, PCR and histo) |

10 min after drinking solution |

89.8 | 100.0 |

| Calvet et al. 2009 [62] | Spain | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms | 199 | 48.2 | 92:107 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | Yes | 8.5% | Any two positive (Histopathology, RUT, UBT, and fecal serology) |

20 min after drinking solution |

99.2 | 60.5 |

| Peng et al. 2009 [63] | Taiwan | Patients underwent upper GI endoscopy | 100 | 55 | 56:44 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | Yes | 4.8% | Culture or combined (Histo and RUT) |

15 min after drinking solution |

100.0 | 95.7 |

| Bruden et al. 2011 [64] | Estonia | Patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy | 280 | 48 | 95:185 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | ≥5% | Culture or (Histo and RUT) |

NM | 93.0 | 88.0 |

| Wardi et al. 2012 [65] | Israel | Patients with partial gastrectomy underwent upper GI endoscopy | 76 | 69.9 | 61:15 | Retrospective cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | 5% | Combined (Histology and rapid urease) and/or culture |

Within 10 to 15 minutes |

64.0 | 91.0 |

| Sahni et al. 2015 [66] | India | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 50 | NM | NM | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | NM | Histo and/or culture | 20 min after administration |

88.0 | 83.0 |

| Li et al. 2017 [67] | China | Patients with gastric cancer | 21,857 | 45.6 | 9360:12,497 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | ≥2.0% | Combined (Histology and rapid urease) and/or culture |

30 min after administration |

94.5 | 92.9 |

| El-Shabrawi et al. 2018 [68] | Egypt | Children with dyspeptic symptoms |

60 | 7.2 | 30:30 | Prospective cross-sectional | 13C | NM | No | >4.0% | Histo and/or culture | 30 min after after ingestion |

89.5 | 95.5 |

| Kwon et al. 2019 [69] | South Korea | Patients with proven H. pylori infection undergone upper GI endoscopy | 562 | 56.3 | 280:282 | Prospective cross-sectional | 13C | NM | Yes | 2.5% | Combined (Histology and rapid urease) and/or culture |

20 minutes after administration | 91.7 | 81.3 |

| Alzoubi et al. 2020 [70] | Jordan | Patients with gastrointestinal diseases symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 60 | 37.3 | 24:36 | Cross-sectional | 13C | NM | Yes | NM | Histo and/or culture | 30 min after ingestion | 94.1 | 76.9 |

| Miftahussurur et al. 2021 [71] | Indonesia | Patients with dyspeptic symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 55 | 19 | 36:19 | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | 57 | Combined (Histology and rapid urease) and/or culture |

10 min after ingestion | 92.3 | 97.6 |

| Hussein et al. 2021 [72] | Iraq | Patients with gastrointestinal diseases symptoms underwent upper GI endoscopy | 115 | 40.3 | 80:35 | Cross-sectional | 14C | NM | No | NM | Histo and/or culture | 10 min after ingestion | 97.5 | 97.0 |

3.3. Unified Findings

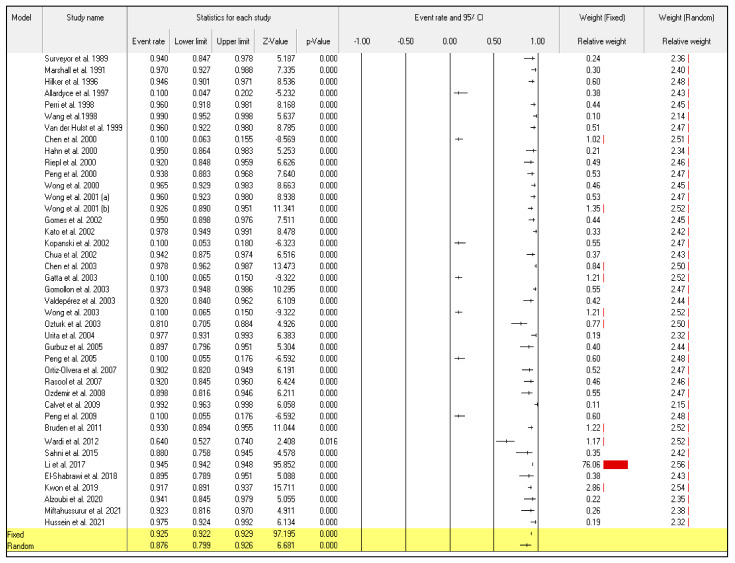

The effect analysis of the 41 included articles ii the current meta-analysis showed that the sensitivity points of estimate were 0.925 and 0.876 according to the fixed and random models, respectively. In addition, the specificity points of estimate were 0.899 and 0.848 according to the fixed and random models, respectively. The Q value calculated by the homogeneity test shows that sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection data have a heterogenous structure (Q = 2137.239; p < 0.001) and (Q = 2689.815; p < 0.001). Accordingly, the author achieved the current meta-analysis following the random-effects model to reduce the misapprehensions produced by the article’s heterogenicity. The total actual heterogeneity between the included articles (tau value) was 1.830 and 1.809 for sensitivity and specificity, respectively.

The obtained high level of heterogeneity, I-squared (I2), 98.128, and 98.516 for the sensitivity and specificity, respectively, indicating that the random effect model for meta-analysis should be applied (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect analysis of included articles.

| Model | Effect Size and 95% Interval | Test of Null (2-Tail) | Heterogeneity | Tau-Squared | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Number of Studies | Point of Estimate | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Z-Value | p-Value | Q-Value | df (Q) | p-Value | I-Squared | Tau Squared | Standard Error | Variance | Tau |

| Sensitivity | ||||||||||||||

| Fixed | 41 | 0.925 | 0.922 | 0.929 | 97.195 | 0.000 | 2137.239 | 40 | 0.000 | 98.128 | 3.350 | 2214 | 4.902 | 1.830 |

| Random | 41 | 0.876 | 0.799 | 0.926 | 6.681 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Specificity | ||||||||||||||

| Fixed | 41 | 0.899 | 0.895 | 0.903 | 95.535 | 0.000 | 2689.815 | 40 | 0.000 | 98.516 | 3.272 | 2.239 | 5.014 | 1.809 |

| Random | 41 | 0.848 | 0.760 | 0.908 | 5.937 | 0.000 | ||||||||

3.4. The Sensitivity and Specificity of 13C/14C-Urea Breath Tests in the Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori Infection

Even though the random-effect meta-analysis showed a high heterogeneity among articles, I2 = 98.128, the pooled event rates and (95%CIs) for the sensitivity and specificity were 0.876 (95%CI: 0.799–0.926) and 0.848 (95%CI: 0.760–0.908), respectively (Figure 2) and (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot from the fixed and random-effects analysis: the sensitivity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Figure 3.

Forest plot from the fixed and random-effects analysis: the specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

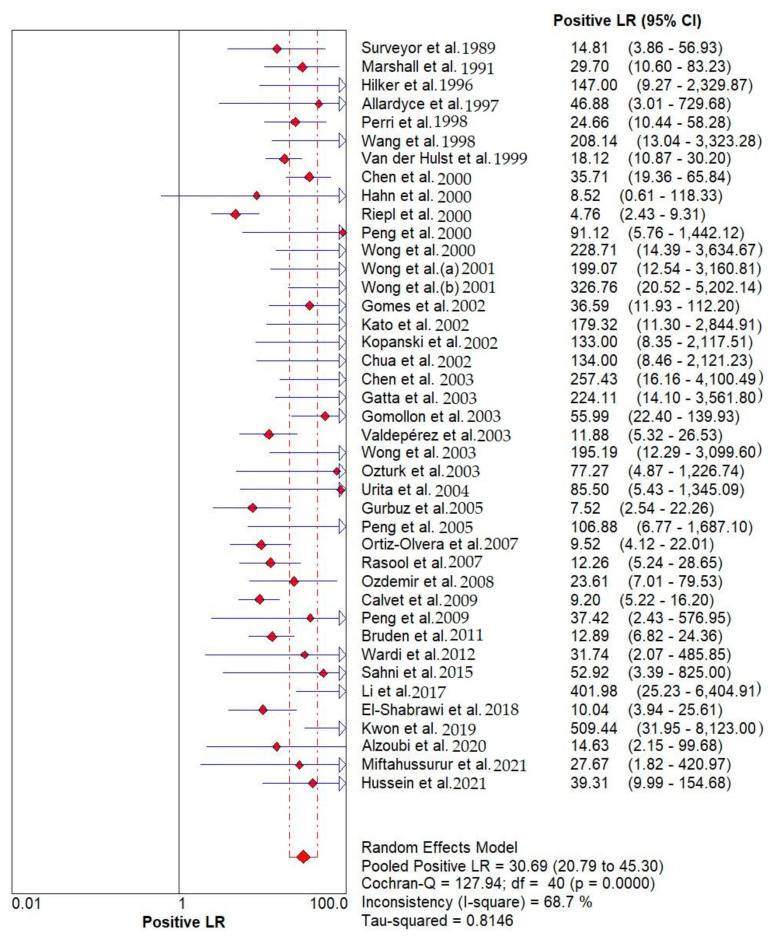

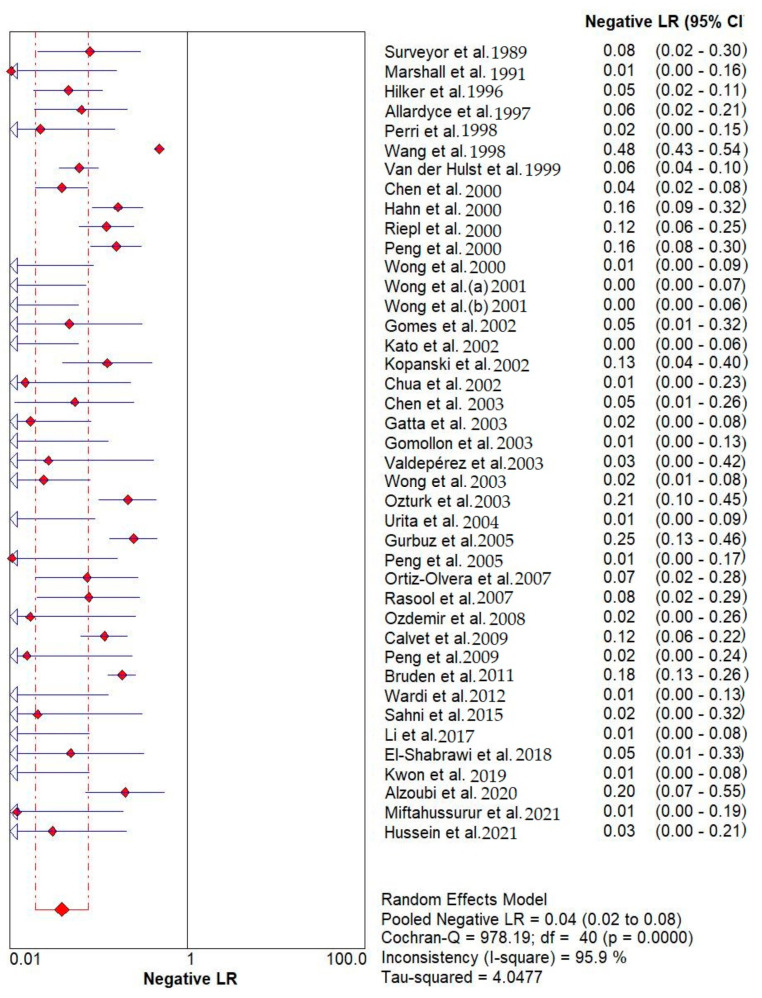

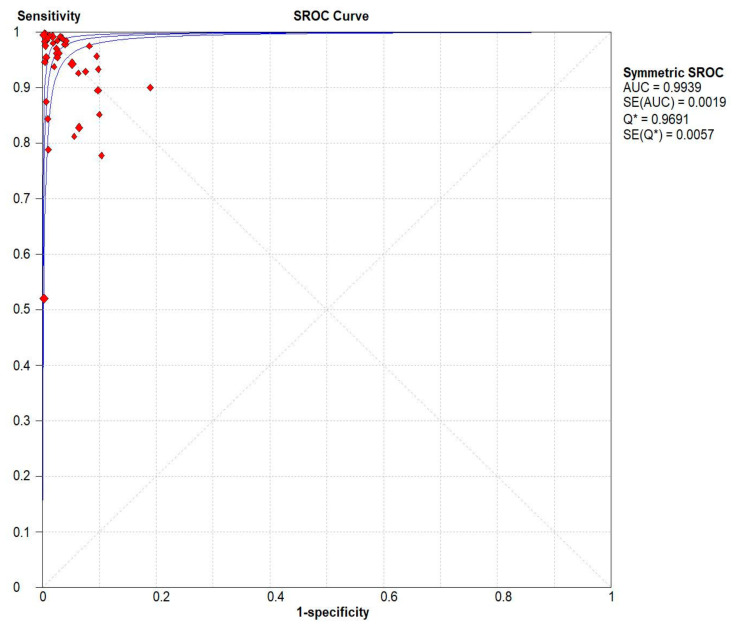

Results indicated that the 13C/14C-urea breath tests have very high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. The pooled urea breath test result. overall likelihood ratio for positive test, overall likelihood ratio for negative test and the symmetric receiver operating characteristics (SROC) curve are presented in Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 4.

Pooled urea breath test result. Overall likelihood ratio for positive test [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Figure 5.

Pooled urea breath test result. Overall likelihood ratio for negative test [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Figure 6.

Pooled urea breath test result. Symmetric receiver operating characteristics (SROC) curve.

3.5. Fail-Safe N Method

The Fail-Safe N was employed to assess the robustness of a significant result by calculating how many studies with effect size zero could be added to the meta-analysis before the result lost statistical significance. The Z-values for observed studies for sensitivity and specificity were 44.48086 and 40.05841, respectively, indicating that the effect value achieved by our meta-analysis is susceptible to publication bias (Table 3).

Table 3.

Classic and Orwin’s Fail-Safe N findings.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Fail-Safe N Method | Orwin’s Fail-Safe N Method | Classic Fail-Safe N Method | Orwin’s Fail-Safe N Method | ||||

| Z-value for observed studies | 44.48086 | The event rate is observed in studies | 0.92518 | Z-value for observed studies | 40.05841 | The event rate is observed in studies | 0.89914 |

| The p-value for observed studies | 0.00000 | The criterion for a “trivial” event rate | 0.50000 | The p-value for observed studies | 0.00000 | The criterion for a “trivial” event rate | 0.50000 |

| Alpha | 0.05000 | Mean event rate in missing studies | 0.50000 | Alpha | 0.05000 | Mean event rate in missing studies | 0.50000 |

| Tails | 2.00000 | Number of missing studies that would bring the p-value to > alpha (N value) | The criterion must fain between other values | Tails | 2.00000 | ||

| Z for alphas | 1.95996 | Z for alphas | 1.95996 | Number of missing studies that would bring the p-value to > alpha (N value) | The criterion must fain between other values | ||

| Number of observed studies | 41.00000 | Number of observed studies | 41.00000 | ||||

| Number of missing studies that would bring the p-value to > alpha (N value) | 1077.00000 | Number of missing studies that would bring the p-value to > alpha (N value) | 7086.00000 | ||||

3.6. Rank Correlation

Begg and Mazumdar test showed a moderate relationship between the sensitivity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, tau with and without continuity correction; values were 0.28729 and 0.28851, respectively. Furthermore, a strong relationship between the sensitivity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, tau with and without continuity correction values were 0.39560 and 0.39683, respectively. Egger’s test for a regression intercept provided p-values of 0.02528 and 0.02771 for sensitivity and specificity, respectively, indicating the presence of publication bias (Table 4).

Table 4.

Kendall’s tau with/without continuity correction and Egger’s regression intercept.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|

| Kendall’s S Statistic (P-Q) | 236.000 | 325.00000 |

| Kendall’s tau with continuity correction | ||

| Tau | 0.28729 | 0.39560 |

| z-value for tau | 2.63951 | 3.63915 |

| p-value (1-tailed) | 0.00415 | 0.00014 |

| p-value (2-tailed) | 0.900830 | 0.00027 |

| Kendall’s tau without continuity correction | ||

| Tau | 0.28851 | 0.39683 |

| z-value for tau | 2.65074 | 3.65038 |

| p-value (1-tailed) | 0.00402 | 0.00013 |

| p-value (2-tailed) | 0.00803 | 0.00026 |

| Egger’s regression intercept | ||

| Intercept | −3.12604 | −3.39677 |

| Standard error | 1.34367 | 1.48526 |

| 95% low limit (2-tailed) | −5.84387 | −6.40099 |

| 95% upper limit (2-tailed) | −0.40820 | −0.39254 |

| t-value | 2.32648 | 2.28698 |

| df | 39.00000 | 39.00000 |

| p-value (1-tailed) | 0.01264 | 0.01385 |

| p-value (2-tailed) | 0.02528 | 0.02771 |

3.7. Publication Bias

The asymmetric funnel plots of the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection suggest publication bias (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Publication bias of the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection.

The subgroup analysis showed that both 13C/14C-urea breath tests have high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection without a significant difference (Table 5).

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis.

| Subgroup | Number of Articles | Sensitivity Effect Size and 95% Confidence Interval |

Specificity Effect Size and 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Urea Breath Tests | 29 | 0.791 (0.742–0.825) | 0.750 (0.700–0.786) |

| 14C-Urea Breath Tests | 12 | 0.780 (0.702–0.831) | 0.766 (0.685–0.816) |

4. Discussion

H. pylori continues to be a serious health issue in the world, contributing significantly to morbidity and mortality from stomach cancer and peptic ulcer disease [1]. Testing for H. pylori is advised in some cases of dyspepsia, after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer, for first-degree relatives with gastric cancer, and in the presence of peptic ulcer disease or low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma [2]. There are numerous testing techniques, both invasive and non-invasive. Endoscopy is necessary for invasive techniques including histology, culture, and fast urease in order to take stomach mucosa biopsies. Despite the excellent specificity of these tests, their sensitivity may be compromised by the localized localization of the infection in the stomach [73]. Additionally, endoscopy might be too resource-intensive and lab facilities might not be able to culture the organism in the under-developed countries, where H. pylori are most common [74].

The carbon urea breath test, stool antigen testing, and blood antibody tests are a few non-invasive tests for H. pylori infection that may be appropriate [3]. The spiral bacterium H. pylori, which has been linked to gastritis, stomach ulcers, and peptic ulcer disease, can be quickly diagnosed by the urea breath test [4]. It is predicated on H. pylori’s capacity to transform urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide. Leading society guidelines support urea breath tests as the primary non-invasive option for identifying H. pylori both before and after treatment [5]. Patients in this study ingest urea that has been labeled with either radioactive carbon-14 or non-radioactive carbon-13, a rare isotope. The detection of isotope-labeled carbon dioxide in the exhaled breath during the following 10 to 30 minutes reveals that the urea was divided; this reveals the presence of urease in the stomach and, consequently, the presence of H. pylori bacteria [6]. The urea breath test has some limitations because it only detects active H. pylori infections; as a result, it will detect less urease if antibiotics are reducing the number of H. pylori present, or if the stomach’s acidity is lower than usual. The test should only be carried out 14 days after ceasing the use of the acid-reducing medicine, such as proton pump inhibitors, or 28 days after ceasing antibiotic therapy. Additionally, a reservoir of H. pylori in dental plaque, according to some physicians, may also have an impact on the outcome of the urea breath test [7].

Determining the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the detection of H. pylori infection was the purpose of the current systematic review and meta-analysis. In all, 5267 studies were found in the literature search for the current meta-analysis. A sample size ranging from 50 to 21857 articles from among them that met the inclusion criteria were included in the final analysis. The primary findings of the present meta-analysis demonstrated that the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the detection of H. pylori infection were between 64 and 100% and 60.5 and 100%, respectively. Further analysis revealed that the fixed and random models’ respective sensitivity points of estimation were 92.5% and 87.6%. The specificity points of estimate for the fixed and random models were 89.9% and 84.8%, respectively.

We showed in this meta-analysis that the 13C/14C-urea breath tests are very sensitive and specific for identifying H. pylori infection. In addition to being non-invasive, the urea breath test has the benefit of offering a thorough evaluation independent of the potential sampling error associated with endoscopic biopsy. Other drawbacks of the biopsy tests include their reliance on the pathologist’s expertise and experience, as well as studies that have shown intern observer variability [8]. The diagnosis of H. pylori infection can be made using a variety of invasive and non-invasive techniques, including endoscopy with biopsy, immunoglobulin titer serology, stool antigen analysis, and the UBT. The non-invasive, user-friendly characteristics of UBT make it possible that this detection technology will be adopted in many therapeutic situations. In the diagnostic assessment of dyspeptic patients with comorbidities that enhance their risk of upper endoscopy, who are unable to undergo upper endoscopy, or who have known or suspected stomach atrophy, UBT can be helpful. The findings of the study imply that UBT has a good diagnostic specificity for identifying H. pylori infection in dyspeptic patients. However, the UBT is an expensive procedure that necessitates specialized carbon dioxide monitoring equipment and radioactive material management infrastructure [9].

The current meta-analysis also revealed that there was significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 98.128 and 98.516 for the sensitivity and specificity, respectively, p-value 0.001), which may be attributed to the use of various types of reference standards, timing between capsule consumption and testing, or differences in the methodological quality of the included studies. The nature of the radioisotope meal and specific patient characteristics may also affect within-study variability, in addition to the urease activity of the oral flora which can affect the reading of the urea breath test, the cut-off value and the time to take the reading after the meal ingestion which were not clearly stated in many of the studies involved. However, despite the fact that our research was unable to identify this difference, it is quite likely that test performance varies across individuals with varied pre-test risks.

Despite earlier meta-analyses discussing the sensitivity and specificity of 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, this study provides updated evidence-based information using a comprehensive search of electronic databases for pertinent publications. The significant drawbacks were the considerable heterogeneity that remained unexplained despite several subgroup analyses, and the fact that only papers published in English were included. In addition, this meta-analysis calculated the sensitivity and specificity of both 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, therefore, separated analysis for 13C and 14C-urea breath tests is recommended. Adults and children who had non-invasive tests to diagnose H. pylori were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The majority of the articles only enrolled symptomatic participants, hence the conclusions of this study only apply to those who have symptoms. Most studies did not include individuals with prior gastrectomy, recent antibiotic or proton pump inhibitor use, or recent gastrectomy. The results of this study therefore do not apply to these populations.

5. Conclusions

For the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, the 13C/14C-urea breath tests are extremely sensitive and specific. The results of this investigation should therefore be regarded with caution because considerable heterogeneity also limits the usefulness of diagnostic meta-analytic estimates. In addition, this meta-analysis calculated sensitivity and specificity of both 13C/14C-urea breath tests in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, therefore, separated analysis for 13C and 14C-urea breath tests is recommended.

Acknowledgments

The author would extend her gratitude to King Saud University for supplying the analysis program. The author is grateful to Samer Abuzerr and Saeed M. Kabrah for their help in some data analysis, article screening, data extraction, and reviewing the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics12102428/s1, Table S1: PRISMA recommendations checklist; Table S2: PubMed search strategy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol of the study was registered at The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, registration No. CRD42022354308).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared that there is no conflict of interest in this work.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pop R., Tăbăran A.-F., Ungur A.P., Negoescu A., Cătoi C. Helicobacter Pylori-induced gastric infections: From pathogenesis to novel therapeutic approaches using silver nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1463. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14071463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford A.C., Yuan Y., Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2020;69:2113–2121. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gisbert J., Calvet X. Helicobacter pylori-negative duodenal ulcer disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;30:791–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan L., Chen Y., Chen F., Tao T., Hu Z., Wang J., You J., Wong B.C., Chen J., Ye W. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric cancer prevention: Updated report from a randomized controlled trial with 26.5 years of follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:154–162.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lahner E., Carabotti M., Annibale B. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in atrophic gastritis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2373. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niknam R., Fattahi M., Sepehrimanesh M., Safarpour A.R. Estimation of Helicobacter pylori positivity in peoples who lived in Kavar city, southern of Iran; Proceedings of the 15th Iranian International Congress of Gasteroentrology and Hepatology (ICGH 2015); Shiraz, Iran. 1–4 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zamani M., Ebrahimtabar F., Zamani V., Miller W., Alizadeh-Navaei R., Shokri-Shirvani J., Derakhshan M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018;47:868–876. doi: 10.1111/apt.14561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamiya S., Backert S. Helicobacter Pylori in Human Diseases. Volume 1149 Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2019. AEMB. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piscione M., Mazzone M., Di Marcantonio M.C., Muraro R., Mincione G. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: A controversial relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:630852. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.630852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung H.-K., Kang S.J., Lee Y.C., Yang H.-J., Park S.-Y., Shin C.M., Kim S.E., Lim H.C., Kim J.-H., Nam S.Y. Evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea 2020. Gut Liver. 2021;15:168. doi: 10.5009/gnl20288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liou J.-M., Malfertheiner P., Lee Y.-C., Sheu B.-S., Sugano K., Cheng H.-C., Yeoh K.-G., Hsu P.-I., Goh K.-L., Mahachai V. Screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer prevention: The Taipei global consensus. Gut. 2020;69:2093–2112. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konturek J.W. Discovery by Jaworski of Helicobacter pylori and its pathogenetic role in peptic ulcer, gastritis and gastric cancer. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Pol. Physiol. Soc. 2003;54:23–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo S.-H., Yeh K.-H., Lin C.-W., Liou J.-M., Wu M.-S., Chen L.-T., Cheng A.-L. Current status of the spectrum and therapeutics of helicobacter pylori-negative mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Cancers. 2022;14:1005. doi: 10.3390/cancers14041005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreri A.J., Montalbán C. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the stomach. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007;63:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laird-Fick H.S., Saini S., Hillard J.R. Gastric adenocarcinoma: The role of Helicobacter pylori in pathogenesis and prevention efforts. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016;92:471–477. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-133997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gravina A.G., Zagari R.M., De Musis C., Romano L., Loguercio C., Romano M. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases: A review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ackerman J. The ultimate social network. Sci. Am. 2012;306:36–43. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0612-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenström B., Mendis A., Marshall B. Helicobacter pylori: The latest in diagnosis and treatment. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2008;37:608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabbagh P., Mohammadnia-Afrouzi M., Javanian M., Babazadeh A., Koppolu V., Vasigala V.R., Nouri H.R., Ebrahimpour S. Diagnostic methods for Helicobacter pylori infection: Ideals, options, and limitations. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;38:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3414-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mentis A., Lehours P., Mégraud F. Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2015;20:1–7. doi: 10.1111/hel.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leide-Svegborn S., Stenström K., Olofsson M., Mattsson S., Nilsson L.-E., Nosslin B., Pau K., Johansson L., Erlandsson B., Hellborg R. Biokinetics and radiation doses for carbon-14 urea in adults and children undergoing the Helicobacter pylori breath test. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1999;26:573–580. doi: 10.1007/s002590050424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raju G., Smith M., Morton D., Bardhan K. Mini-dose (1-microCi) 14C-urea breath test for the detection of Helicobacter pylori. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1027–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perri F., Festa V., Clemente R., Quitadamo M., Andriulli A. Methodological problems and pitfalls of urea breath test. Ital. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1998;30:S315–S319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epple H., Kirstein F., Bojarski C., Frege J., Fromm M., Riecken E., Schulzke J. 13C-Urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori diagnosis and eradication correlation to histology, origin of ‘false’results, and influence of food intake. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997;32:308–314. doi: 10.3109/00365529709007677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chey W.D., Wong B.C. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferwana M., Abdulmajeed I., Alhajiahmed A., Madani W., Firwana B., Hasan R., Altayar O., Limburg P.J., Murad M.H., Knawy B. Accuracy of urea breath test in Helicobacter pylori infection: Meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG. 2015;21:1305. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i4.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham D., Evans D., Jr., Alpert L., Klein P., Evans D., Opekun A., Boutton T. Campylobacter pylori detected noninvasively by the 13C-urea breath test. Lancet. 1987;329:1174–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)92145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armijo-Olivo S., Stiles C.R., Hagen N.A., Biondo P.D., Cummings G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: Methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012;18:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas H. Effective Public Health Practice Project. McMaster University; Hamilton, ON, Canada: 2003. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DerSimonian R., Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: An update. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2007;28:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surveyor I., Goodwin C.S., Mullan B.P., Geelhoed E., Warren J.R., Murray R.N., Waters T.E., Sanderson C.R. The 14C-urea breath-test for the detection of gastric Campylobacter pylori infection (for editorial comment, see page 426; see also page 431) Med. J. Aust. 1989;151:435–439. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb101252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall B.J., Plankey M.W., Hoffman S.R., Boyd C.L., Dye K.R., Frierson Jr H.F., Guerrant R.L., McCallum R.W. A 20-minute breath test for Helicobacter pylori. Am. J. Gastroenterol. Springer Nat. 1991;86:438–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilker E., Domschke W., Stoll R. 13C-urea breath test for detection of Helicobacter pylori and its correlation with endoscopic and histologic findings. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1996;47:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allardyce R.A., Chapman B.A., Tie A.B., Burt M.J., Yeo K.J., Keenan J.I., Bagshaw P.F. 37 kBq 14C-urea breath test and gastric biopsy analyses of H. pylori infection. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1997;67:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perri F., Clemente R., Festa V., Annese V., Quitadamo M., Rutgeerts P., Andriulli A. Patterns of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and delayed gastric emptying. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2082–2088. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W.-M., Lee S.-C., Ding H.-J., Jan C.-M., Chen L.-T., Wu D.-C., Liu C.-S., Peng C.-F., Chen Y.-W., Huang Y.-F. Quantification of Helicobacter pylori infection: Simple and rapid 13C-urea breath test in Taiwan. J. Gastroenterol. 1998;33:330–335. doi: 10.1007/s005350050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Der Hulst R.W., Hensen E.F., Van Der Ende A., Kruizinga S.P., Homan A., Tytgat G.N. Laser-assisted 13C-urea breath test; a new noninvasive detection method for Helicobacter pylori infection. Nederlands Tijdschrift Geneeskunde. 1999;143:400–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X., Haruma K., Kamada T., Mihara M., Komoto K., Yoshihara M., Sumii K., Kajiyama G. Factors that affect results of the 13C urea breath test in Japanese patients. Helicobacter. 2000;5:98–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahn M., Fennerty M.B., Corless C.L., Magaret N., Lieberman D.A., Faigel D.O. Non-invasive tests as a substitute for histology in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2000;52:20–26. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.106686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riepl R., Folwaczny C., Otto B., Klauser A., Blendinger C., Wiebecke B., König A., Lehnert P., Heldwein W. Accuracy of 13C-urea breath test in clinical use for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Z. für Gastroenterol. 2000;38:13–19. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-15278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng N.J., Hsu P.I., Lee S.C., Tseng H.H., Huang W.K., Tsay D.G., Ger L.P., Lo G.H., Lin C.K., Tsai C.C. A 15-minute [13C]-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000;15:284–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong W., Wong B., Wong K., Fung F., Lai K., Hu W., Yuen S., Leung S., Lau G., Lai C. 13C-urea breath test without a test meal is highly accurate for the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;14:1353–1358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong W., Wong B., Li T., Wong K., Cheung K., Fung F., Xia H., Lam S. Twenty-minute 50 mg 13C-urea breath test without test meal for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;15:1499–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong B., Wong W., Wang W., Tang V., Young J., Lai K., Yuen S., Leung S., Hu W., Chan C. An evaluation of invasive and non-invasive tests for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;15:505–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomes A.T.B., Coelho L.K., Secaf M., Módena J.L.P., Troncon L.E.d.A., Oliveira R.B.d. Accuracy of the 14C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2002;120:68–70. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802002000300002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kato S., Ozawa K., Konno M., Tajiri H., Yoshimura N., Shimizu T., Fujisawa T., Abukawa D., Minoura T., Iinuma K. Diagnostic accuracy of the 13C-urea breath test for childhood Helicobacter pylori infection: A multicenter Japanese study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1668–1673. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kopański Z., Jung A., Wasilewska-Radwańska M., Kuc T., Schlegel-Zawadzka M., Witkowska B. Comparative diagnostic value of the breath test and the urine test with 14C-urea in the detection of the Helicobacter pylori infection. Nucl. Med. Rev. 2002;5:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chua T., Fock K., Teo E., Ng T. Validation of 13C-Urea Breath Test for the Diagnosis of Helicobacter Pylori Infection in the Singapore Population. Singap. Med. J. 2002;43:408–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen T.S., Chang F.Y., Chen P.C., Huang T.W., Ou J.T., Tsai M.H., Wu M.S., Lin J.T. Simplified 13C-urea breath test with a new infrared spectrometer for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2003;18:1237–1243. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gatta L., Vakil N., Ricci C., Osborn J., Tampieri A., Perna F., Miglioli M., Vaira D. A rapid, low-dose, 13C-urea tablet for the detection of Helicobacter pylori infection before and after treatment. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;17:793–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gomollon F., Ducons J., Santolaria S., Omiste I.L., Guirao R., Ferrero M., Montoro M. Breath test is very reliable for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in real clinical practice. Dig. Liver Dis. 2003;35:612–618. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(03)00373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valdepérez J., Vicente R., Novella M., Valle L., Sicilia B., Yus C., Gomollón F. Is the breath test reliable in primary care diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection? Aten. Primaria. 2003;31:93–97. doi: 10.1016/S0212-6567(03)79144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong W., Lam S., Lai K., Chu K., Xia H., Wong K., Cheung K., Lin S., Wong B. A rapid-release 50-mg tablet-based 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;17:253–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Öztürk E., Yeşilova Z., Ilgan S., Arslan N., Erdil A., Celasun B., Özgüven M., Dağalp K., Ovali Ö., Bayhan H. A new, practical, low-dose 14C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection: Clinical validation and comparison with the standard method. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2003;30:1457–1462. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urita Y., Hike K., Torii N., Kikuchi Y., Kanda E., Kurakata H., Sasajima M., Miki K. Breath sample collection through the nostril reduces false-positive results of 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig. Liver Dis. 2004;36:661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gurbuz A., Ozel A., Narin Y., Yazgan Y., Baloglu H., Demirturk L. Is the remarkable contradiction between histology and 14C urea breath test in the detection of Helicobacter pylori due to false-negative histology or false-positive 14C urea breath test? J. Int. Med. Res. 2005;33:632–640. doi: 10.1177/147323000503300604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng N.-J., Lai K.-H., Liu R.-S., Lee S.-C., Tsay D.-G., Lo C.-C., Tseng H.-H., Huang W.-K., Lo G.-H., Hsu P.-I. Capsule 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG. 2005;11:1361. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nayeli N.O.-O., Villota S.M., Wong I.G., Valencia J.B., Muñoz L.C. Validation of a simplified 13C-urea breath test method for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2007;99:392–397. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082007000700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rasool S., Abid S., Jafri W. Validity and cost comparison of 14carbon urea breath test for diagnosis of H. Pylori in dyspeptic patients. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG. 2007;13:925. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Özdemir E., Karabacak N.I., Deḡertekin B., Cırak M., Dursun A., Engin D., Ünal S., Ünlü M. Could the simplified 14C urea breath test be a new standard in non-invasive diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection? Ann. Nucl. Med. 2008;22:611–616. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calvet X., Sánchez-Delgado J., Montserrat A., Lario S., Ramírez-Lázaro M.J., Quesada M., Casalots A., Suárez D., Campo R., Brullet E. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori: A reappraisal. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:1385–1391. doi: 10.1086/598198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peng N.-J., Lai K.-H., Lo G.-H., Hsu P.-I. Comparison of non-invasive diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection. Med. Princ. Pract. 2009;18:57–61. doi: 10.1159/000163048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bruden D.L., Bruce M.G., Miernyk K.M., Morris J., Hurlburt D., Hennessy T.W., Peters H., Sacco F., Parkinson A.J., McMahon B.J. Diagnostic accuracy of tests for Helicobacter pylori in an Alaska Native population. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG. 2011;17:4682. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i42.4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wardi J., Shalev T., Shevah O., Boaz M., Avni Y., Shirin H. A rapid continuous-real-time 13C-urea breath test for the detection of Helicobacter pylori in patients after partial gastrectomy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012;46:293–296. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823eff09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sahni H., Palshetkar K., Shaikh T.P., Ansari S., Ghosalkar M., Oak A., Khan N. Comparison between rapid urease test and carbon 14 urea breath test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. IJRMS. 2017;3:2362–2365. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20150632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Z.-X., Huang L.-L., Liu C., Formichella L., Zhang Y., Wang Y.-M., Zhang L., Ma J.-L., Liu W.-D., Ulm K. Cut-off optimization for 13C-urea breath test in a community-based trial by mathematic, histology and serology approach. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:2072. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02180-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Shabrawi M., Abd El-Aziz N., El-Adly T.Z., Hassanin F., Eskander A., Abou-Zekri M., Mansour H., Meshaal S. Stool antigen detection versus 13C-urea breath test for non-invasive diagnosis of pediatric Helicobacter pylori infection in a limited resource setting. Arch. Med. Sci. 2018;14:69–73. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.61031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kwon Y.H., Kim N., Yoon H., Shin C.M., Park Y.S., Lee D.H. Effect of citric acid on accuracy of 13C-urea breath test after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in a region with a high prevalence of atrophic gastritis. Gut Liver. 2019;13:506. doi: 10.5009/gnl18398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alzoubi H., Al-Mnayyis A.a., Al Rfoa I., Aqel A., Abu-Lubad M., Hamdan O., Jaber K. The use of 13C-urea breath test for non-invasive diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in comparison to endoscopy and stool antigen test. Diagnostics. 2020;10:448. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10070448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miftahussurur M., Windia A., Syam A.F., Nusi I.A., Alfaray R.I., Fauzia K.A., Kahar H., Purbayu H., Sugihartono T., Setiawan P.B. Diagnostic value of 14C urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori detection compared by histopathology in indonesian dyspeptic patients. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2021;14:291. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S306626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hussein R.A., Al-Ouqaili M.T., Majeed Y.H. Detection of Helicobacter Pylori infection by invasive and non-invasive techniques in patients with gastrointestinal diseases from Iraq: A validation study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0256393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kalem F., Ozdemir M., Baysal B. Investigation of the presence of Helicobacter pylori by different methods in patients with dyspeptic complaints. Mikrobiyoloji Bul. 2010;44:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dore M.P., Pes G.M. What is new in Helicobacter pylori diagnosis. An overview. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:2091. doi: 10.3390/jcm10102091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.