Abstract

Community integration is important to address among homeless-experienced individuals. Little is known about helping veteran families (families with a parent who is a veteran) integrate into the community after homelessness. We sought to understand the experiences of community integration among homeless-experienced veteran families. We used a two-stage, community-partnered approach. First, we analysed 16 interviews with homeless-experienced veteran parents (parents who served in the military; n = 9) living in permanent housing and providers of homeless services (n = 7), conducted from February to September 2016, for themes of community integration. Second, we developed a workgroup of nine homeless-experienced veteran parents living in a permanent housing facility, who met four times from December 2016 to July 2017 to further understand community integration. We audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed the interviews and workgroups for community integration themes. For the analysis, we developed community integration categories based on interactions outside of the household and built a codebook describing each topic. We used the codebook to code the individual interviews and parent workgroup sessions after concluding that the workgroup and interview topics were consistent. Findings were shared with the workgroup. We describe our findings across three stages of community integration: (a) first housed, (b) adjusting to housing and the community, and (c) housing maintenance and community integration. We found that parents tended to isolate after transitioning into permanent housing. After this, families encountered new challenges and were guarded about losing housing. One facilitator to community integration was connecting through children to other parents and community institutions (e.g. schools). Although parents felt safe around other veterans, many felt judged by non-veterans. Parents and providers reported a need for resources and advocacy after obtaining housing. We share implications for improving community integration among homeless-experienced veteran families, including providing resources after obtaining housing, involving schools in facilitating social connections, and combating stigma.

Keywords: community integration, families, homeless persons, housing, qualitative research, social integration, veterans

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Veteran homelessness has dropped nearly 50% in the United States (US) since 2009 (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development, 2020). This progress is tied to efforts of the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) homeless service programs, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing Programs and rapid-rehousing and homelessness prevention through Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) (Austin et al., 2014; Silverbush et al., 2017).

Although permanent housing is essential to addressing homelessness (Evans et al., 2019), community integration – belonging to and participating within the community – is also important to address among veterans who have experienced homelessness (hereafter ‘homeless-experienced’ veterans) (Chinchilla, Gabrielian, Glasmeier, et al., 2019; Chinchilla, Gabrielian, Hellemann, et al., 2019; McColl et al., 2001). Wong and Solomon (2002) conceptualised community integration for individuals in supportive housing as comprised of physical, social and psychological components. Physical integration involves participating in physical activities in one’s community; social integration includes social roles and interactions with community members; and psychological integration refers to a sense of belonging (Wong & Solomon, 2002). Although community integration is important for recovery, research demonstrates the challenges of addressing community integration among adults in supportive housing (Tsai et al., 2012). Yanos et al. (2004) found that individuals with severe mental illness voiced challenges, including difficulty being housed alone, safety concerns, and fears of fitting in among some neighbourhoods, after receiving housing. Homeless-experienced individuals living in scatter-site settings may guard themselves against becoming close to others due to exploitation fears (Henwood et al., 2015).

Veterans are a subset of the homeless-experienced population that may face dual issues of community integration – both integrating into the civilian community after military service and after homelessness (Elnitsky & Kilmer, 2017). Further, thirty percent of female veterans and 9% of male veterans had dependent children when homeless (Tsai et al., 2015). Despite growing research about community integration among individual adults, community integration after homelessness among veteran families is poorly understood.

Stressors that may impact community integration for homeless-experienced families include child welfare involvement (Shinn et al., 2017), and parenting and mental health stressors (Hayes et al., 2013; Paquette & Bassuk, 2009; Zabkiewicz et al., 2014). Typical family programs consist of case management in housing programs that do not address community integration (Bassuk et al., 2014). Although SSVF successfully houses veteran families, it is a rapid-rehousing and short-term crisis response program that does not focus on longer-term community integration (Silverbush et al., 2017).

Qualitative inquiry is a powerful tool to understand community integration among under-resourced populations (Israel et al., 2005). Yet, qualitative studies examining community integration largely concentrate on individuals with severe mental illness and homeless experiences, rather than parents with children in supportive housing. One study identified experiences of receiving help, minimising risk, avoiding stigma, and giving back as important for community integration among individuals with severe mental illness (Bromley et al., 2013). Authors found that having a severe mental illness – which is less prevalent among homeless-experienced parents with children – played a role in shaping the type of community valued by participants, particularly communities that felt safe and supportive (Bromley et al., 2013; Tsai et al., 2015). Prior work has also focused on social integration. One study showed that homeless-experienced veterans in stable housing relied on formal (case management) and informal (12-step sponsors and peers) supports to remain housed; authors concluded a need for greater social supports in maintaining housing (Gabrielian et al., 2018). An Australian study found that housing did not lead to social integration, and individuals relied on prior connections with homeless peers (Bower et al., 2018). Similarly, a meta-synthesis of individuals with mental illness living in supportive housing found issues of loneliness and stigma (Watson et al., 2019). One study of formerly homeless mothers found that none received assistance for integrating into their new communities (Tischler, 2008). Another study of formerly homeless mothers found that having children increased psychological integration (Nemiroff et al., 2011). Although these studies are important, they do not highlight the experiences of veteran families.

To identify unmet need and inform programs for veteran families, we sought to understand the community integration experiences and barriers of homeless-experienced veteran families living in permanent housing. We analysed interviews conducted with homeless-experienced veteran parents and homeless service providers, and workgroup sessions with homeless-experienced veteran parents, to highlight the voices of veteran families and inform recommendations for enhancing community integration.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Design: Qualitative, community-partnered, two-stage approach

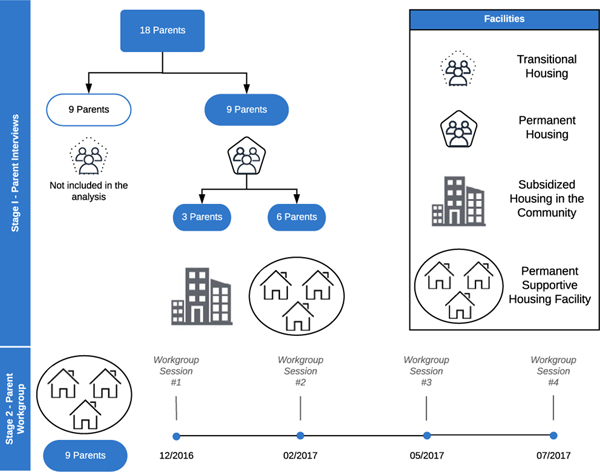

We utilised a two-stage, community-partnered participatory research approach, using a qualitative descriptive design, to highlight the voice of participants (Jones & Wells, 2007). The purpose of stage 1 was to develop an initial understanding of the experiences and barriers to community integration of recently housed veteran families through analysing interviews conducted with parents and providers for themes of community integration. The purpose of stage 2 was to assemble a workgroup of parents in permanent supportive housing to develop an enhanced understanding of community integration through discussion amongst homeless-experienced parents, including testing the interview themes to see if they were shared among workgroup members, and eliciting recommendations for services (Figure 1). Community partners, including homeless-experienced veteran parents and homeless service providers, helped develop the individual interview guide and provided feedback on findings. The Institutional Review Board reviewed all materials and formally designated all activities as quality improvement activities.

FIGURE 1.

Parent interviews and workgroup sessions. In Stage 1, we analyzed interviews conducted with homeless-experienced veteran parents and providers of homeless services for an initial understanding of community integration. We included 9 parents living in permanent housing in the analysis. Of the 9 parents living in permanent housing, 3 were living in subsidized housing in the community, and 6 at a permanent supportive housing facility. In Stage 2, we developed a workgroup of 9 recently housed parents living at one permanent supportive housing facility who met for four sessions

2.2 |. Stage 1: Individual interviews with parents and providers

As part of a larger project to understand the experiences, barriers and needs of homeless-experienced veteran families, we conducted 25 semi-structured interviews from February to September 2016 with 18 homeless-experienced veteran parents (homeless within 2 years), and seven homeless services providers. This paper concentrates on the topic of community integration after obtaining housing through an analysis of the interviews completed with veteran parents living in permanent housing at the time of the interviews (n = 9), and homeless services providers (n = 7). We did not include the nine parents living in transitional housing as these parents had not obtained permanent housing (Figure 1).

2.2.1 |. Procedures

For the larger project, we recruited veteran parents who: (a) had a recent homelessness history (within 2 years), (b) had custody of and were living with a child/youth, and (c) were VA healthcare eligible. We recruited parents from multiple Southern California facilities serving homeless-experienced veteran families, including one transitional housing facility, one transitional and permanent supportive housing organisation, one permanent supportive housing facility, and a VA homeless clinic. Transitional housing facilities provide interim housing, and permanent supportive housing facilities provide long-term housing with rent assistance and case management (Bassuk et al., 2014). We recruited providers working with homeless-experienced veteran families from four transitional and permanent supportive housing facilities, including facilities where we recruited parents.

We recruited veteran parents through letters, flyers, and referrals. Homeless service providers were recruited through staff referrals. We purposefully sampled veteran mothers and fathers living with their child/youth and providers from sites that served homeless-experienced veteran families, given the clandestine nature of family homelessness. Parents and providers met eligibility criteria for the larger project. Across the sites, providers’ roles included providing case management, supportive services and clinical programming. All parents interviewed were veterans; we did not interview veterans’ partners. We were limited by the Paperwork Reduction Act (1995) – designed to minimise burdens on the public by federally sponsored data collection without additional permissions – to interviewing nine mothers and nine fathers.

The interviews were conducted in English by a trained interviewer and child psychiatrist (RIM) in confidential areas at the residence or VA facility. Participants were asked about being a mother or father in the context of different sectors of their lives affected by homelessness (e.g. relationships, health/mental health, children, transport, shelter, food, safety, income). The semi-structured interview guide asked participants: (a) the experience of being a veteran mother or father when homeless; (b) barriers/facilitators to services within each sector; and (c) recommendations for improving services. Providers were asked parallel questions covering the same sectors (e.g. their experiences working with homeless-experienced veteran families, barriers/facilitators to services within the sectors, and recommendations for improvement). Prior to obtaining verbal consent, the interviewer ensured that all participants understood that involvement in interviews was confidential, voluntary, would not affect housing and could be stopped. Parents also completed a brief demographic questionnaire. Parents received vouchers to exchange for $25 in cash at the VA facility; providers were not compensated. All interviews lasted up to 60 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed.

2.2.2 |. Data analysis

Research team members reviewed the interview transcripts for major domains of inquiry regarding community integration, determined as consisting of any interactions outside the household. One team member (RIM) selected quotes relating to community integration. Next, three members trained in qualitative analysis (RIM, SF, GR) preliminarily developed categories of community integration (e.g. interaction with veterans, interaction with others). We used Solomon and Wong’s framework of community integration to develop the codebook (Wong & Solomon, 2002). One team member (RIM) pile sorted all quotes regarding community integration into the chosen categories. To ensure consistency, a second team member (SF) independently matched the community integration quotes to the determined categories; a kappa was calculated to be >0.70 indicating sufficient agreement. Any discrepancies were settled by a third team member (NB) independently matching the quotes to the categories. Analysis confirmed saturation of themes, that ideas fit within the thematic categories and no new ideas or themes were introduced (Bowen, 2008). We used Microsoft Excel (2016) to manage the codes. We discussed the themes with workgroup parents to protect against researcher bias.

2.3 |. Stage 2: Parent workgroup

To expand upon information from the interviews and to obtain further recommendations, we assembled a workgroup of homeless-experienced veteran parents (n = 9) from a permanent supportive housing facility in Southern California serving predominantly veteran families. The workgroup sessions occurred from December 2016 to July 2017 (Figure 1).

2.3.1 |. Procedures

Veteran parents were recruited through flyers and letters at the housing facility. Parents were eligible to participate in the workgroup if they were a veteran eligible for services, had a history of homelessness within 2 years, were guardians of and living with a child/youth, and could participate. One parent who volunteered to participate could not confirm being a veteran eligible for services; all other volunteers met criteria.

The workgroup met for four 90-min sessions. We held the sessions during family gatherings at the facility around seasonal festivities (winter holidays, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, and July Fourth). While workgroup parents met privately, family members worked on crafts/family activities with staff. Four sessions were led by one team member (RIM), assisted by another trained team member (SF) for three sessions. Parents were informed that participation was voluntary, confidential, would not affect their housing, and could be discontinued. Verbal consent was obtained before sessions. Workgroup members were provided with $20 vouchers redeemable for cash for each session. Sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed.

The first session focused on developing an understanding of community integration. The second session focused on barriers encountered when integrating into the community. Parents engaged in a group data elicitation technique and listed barriers to integrating into the community on notecards and sorted them into groups. During the third session, parents reviewed and validated community integration findings from the interviews and previous groups. In the fourth session, parents discussed community integration recommendations. Parents gave self-reported information about their race/ethnicity, and number of children.

2.3.2 |. Data analysis

After reviewing the session transcripts and concluding that the topics discussed were consistent with the individual interviews, we elected to use the codebook for community integration developed in Stage 1 to code the sessions. Three team members (RIM, SF, NB) coded the transcripts using qualitative data analysis software Atlas-ti Version 7.1 (ATLAS.ti, 2013). To ensure completeness, we used a general rule of including text if there were doubts. We discussed questionable text as a team, and resolved all discrepancies with the team leader (RIM) through iterative discussion.

3 |. FINDINGS

3.1 |. Demographic characteristics

3.1.1 |. Interviews

Table 1 captures the demographics of the nine parents interviewed. Table 2 summarises the provider settings.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of parents individually interviewed

| (N = 9) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 44.4% |

| Female | 55.6% |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black/not Latino | 11.1% |

| Latino/any race | 55.6% |

| Caucasian/not Latino | 22.2% |

| 2+ races/not Latino | 11.1% |

| Age | |

| Mean | 39.3 years |

| Median number of children/youth in custody | |

| Median | 1 child |

| Age range of children | |

| Range | 8 months-17 years |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 22.2% |

| Married/living with significant other | 44.4% |

| Divorced | 33.3% |

| Reported most recent episode of homelessness | |

| Mean | 6.56 months |

| Range | 2–12 months |

TABLE 2.

Settings of providers interviewed

| Providers (N = 7) | Settings |

|---|---|

| Provider 1 | Transitional housing |

| Provider 2 | Transitional housing |

| Provider 3 | Permanent supportive housing |

| Provider 4 | Permanent supportive housing |

| Provider 5 | Transitional housing |

| Provider 6 | Transitional housing and permanent housinga |

| Provider 7 | Transitional housing and permanent housinga |

Note: Although some providers worked in transitional housing facilities, all providers had knowledge of family experiences after receiving permanent supportive housing from working with homeless-experienced veteran families.

Provider 6 and 7 worked in transitional housing settings but provided services to clients in both settings.

3.1.2 |. Workgroup

Nine veteran parents (six mothers, three fathers) participated in the workgroup sessions. Between three and seven parents attended each session. Three mothers did not return after the first, and one joined after the second session. All lived in the same permanent supportive housing facility. Parents were not asked about marital status, however some self-reported living with a partner, some were single. Parents had a median number of two children. Of the workgroup members who disclosed their race/ethnicity, one identified as other, one as Native American, one as White, and one as Black.

3.2 |. Thematic findings

There was concordance in the themes across the individual interviews and workgroup sessions. The themes generated in the workgroup aligned with and validated the individual interviews; no additional themes were generated. We present the findings of the individual interviews and workgroup sessions together.

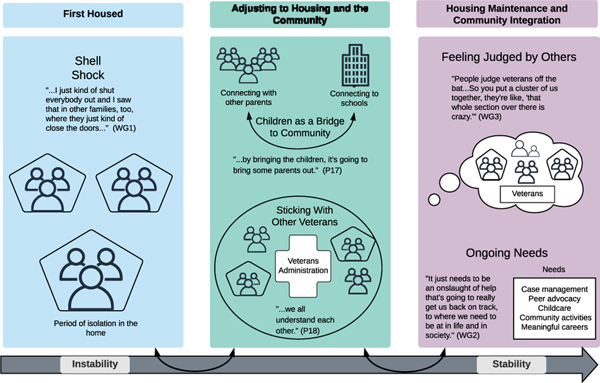

Different stages of transition after receiving permanent housing became obvious from the participants’ stories. We identified three stages of community integration for homeless-experienced veteran families from the data: (a) first housed, (b) adjusting to housing and the community, and (c) housing maintenance and community integration. Across these stages, experiences were divided into: (a) housing experiences and (b) social interactions. Below, we present the themes across stages of the community integration process with supportive quotes. Figure 2 depicts the conceptual model of community integration among homeless-experienced veteran families derived from the interviews and workgroup findings.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual model for community integration among homeless-experienced veteran families. When families were first housed they often underwent a stage of “shell shock,” in which they isolated within their homes while navigating the transition from homelessness to being housed. During the next stage, as families adjusted to being housed and to the community, many drew upon support from other veteran families. During this stage, parents conveyed that children can serve as a bridge to other parents and institutions in the community, such as schools. During the stage of housing maintenance and community integration, parents expressed feeling judged or misunderstood by non-veterans in the community and needing ongoing supports to continue to move forward. Arrows underneath the stages denote that although the overall trajectory is towards stability, families can move back and forth between the experiences. P, parent; WG, workgroup

3.3 |. First housed

3.3.1 |. Housing experience: Shell shock

A theme developed of families experiencing ‘shell shock’ when they obtained permanent housing. This theme consisted of parents turning inward, remaining at home, and isolating. Although this theme was strongest among workgroup parents who were living in the same housing facility, it was also described in many interviews. One workgroup member described witnessing this process among families at the facility:

“…they’ve been through whatever they’ve been through, their hardship, they…close the doors and be like a cocoon….” (WG 1)

Parents and providers described that isolating could be due to safety concerns and to safeguard against additional trauma. Providers explained a fear of re-traumatisation among parents with PTSD, especially women with military sexual trauma (MST):

“…there’s a lot of military sexual trauma, domestic violence, PTSD….They might know their next door neighbor but there’s also this fearfulness of what are they going to ask me….” (Provider 3)

Parents also described isolating due to emotional difficulties of navigating the transition from homelessness to obtaining housing. One parent voiced this struggle to leave homelessness stressors behind:

“When you’ve been stressing so long and you wake up in the morning, you figure out how you’re going to feed your kids at night, where you guys are going to stay at night, what’s going to be stolen from you today….I think the longer you’re here [permanent housing], the more relaxed you get.” (WG 3)

A housing provider echoed this sentiment, explaining how she tried to help parents adjust by telling them, “…this is your home. You can unpack the boxes” (Provider 3).

Parents described positive reasons for isolating. One mother, who was homeless with her young child for months before receiving housing explained:

“I think that they’re really happy in their home…knowing that they can just stretch and [have] a peace of mind because the children can play….maybe this is probably the first best place they’ve ever had.” (Parent 17)

3.3.2 |. Social interactions: Offering support to others

As a result of this initial period of ‘shell shock’, social interaction was often kept to a minimum. Parents described this as taxing:

“…they [other families] just kind of close the doors and just deal with our kids in our own home….And it was very difficult…because there wasn’t anybody for me to talk to….” (WG 1)

However, parents who had been through this stage described empathising with newly housed families and offering support. One father presented a bible study to other veteran parents, while a mother provided help, “…my neighbor, I told her if you need something, just let me know” (Parent 17).

3.4 |. Adjusting to housing and the community

3.4.1 |. Housing experience: Which fire do you put out?

After the initial period of obtaining housing, a theme developed of ongoing challenges and threats to the family’s well-being, including fears of losing housing. One parent explained, “…you feel like…this is too good to be true. When is it going to go?” (WG 3). Another described, “I’m constantly saying to my kids, ‘don’t touch nothing….We may get evicted’” (WG 3).

Parents described new and different challenges during the transition:

“Help us figure out the transition because we’ve got new problems now. It was easier when you’re homeless because you know what you got to do….” (WG 3)

They brought up problems managing time (“do I have to pay this bill today or can I rest today…?” (WG 3)), finding employment, obtaining benefits, and addressing mental health. A parent described this constant juggle:

“If you’re worried about the kids, you forget about the food or the car….” (WG 1)

One provider detailed the stressors families faced in permanent housing:

“There’s food scarcity. There’s a lot of transportation issues….cars aren’t running well or they need gas or they overstretched their credit or their income….” (Provider 3)

Money remained a concern. A father living in federally subsidised housing with his daughter commented on this fear:

“...I still have that fear, what if I don’t get that money for this, am I going to lose everything? What’s going to happen with my daughter?” (Parent 13)

3.4.2 |. Social interactions: Children as a bridge

During this period, children in the families often served as the bridge to interacting with other parents and community institutions. A workgroup parent explained, “…the kids have to pull us as parents to get outside of the house, so they’re able to play” (WG 2). Interactions occurred at local WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children) offices, parks, schools, and churches. One parent kept her sons in their previous school to keep their peer relationships intact, despite driving long distances to the school. Parents explained how schools serve as a hub:

“…your world is around your children, which is going to involve their school and their activities.” (WG 4)

However, multiple parents felt like strangers to those around them and called for structured child and family activities to build community. One mother explained:

“We live in a community full of other veterans and I know that there’s other kids here….how come they haven’t focused on the children here if this is family?” (Parent 14)

3.4.3 |. Social interactions: Sticking with other veterans

Most parents interviewed individually and in the workgroup desired to be among other veterans during the transition into the community. Parents described comfort in their proximity to other veterans and felt that veteran families understood and trusted each other, and shared values: “…all of us have that one connection that we’re all prior military” (WG 1). One mother living in an apartment in the community noted, “I feel safe when I’m around my veterans” (Parent 6). Some parents felt that being around other veterans helped with community integration:

“…there’s a camaraderie with people that are military that I think it helps with the assimilation.” (Parent 11)

Parents in housing facilities with other veterans relied on each other for assistance:

“…we help each other out. If I need to go somewhere and I don’t have a car, our neighbors do. And we do the same.” (Parent 18)

3.5 |. Housing maintenance and community integration

3.5.1 |. Social interactions: Feeling judged by others

Despite their interactions through schools and with neighbours, an overwhelming theme was evident of veterans feeling judged by civilians. One parent, who felt negatively viewed for being both a veteran and formerly homeless questioned, “how are we supposed to get… outside in the community, if we’re steady being ridiculed…?” (WG 2). A mother described feeling doubly judged for being recently homeless and disabled; she felt others assumed she was receiving financial compensation for her disability and should be more financially stable:

“…they’re thinking like, ‘okay, you should be rich. You should be able to live above normal people’…being a disabled vet and homeless is bad…people look at it like, ‘oh, wow, you know, you’re disabled and you could do this, you could do that.’ I’m like, ‘no, you can’t’.”(Parent 6)

Parents described feeling misunderstood by civilians and providers about their skillsets when seeking employment. One father commented:

“…I came from working on…an F18…when someone’s life depending on you…and then you come back and they’re [provider] telling you things like oh, you’re going to work security for $6…You were in the military and it’s kind of like a slap in the face….” (Parent 11)

Parents in the workgroup perceived heightened judgement and felt viewed as ‘crazy’ by civilians because they lived within the same housing facility as other veterans and were associated with the military. Although not universal, some workgroup parents felt judged by staff and parents at their child’s school. One parent reported:

“I think it’s a biasness that they [the school staff] have. Once you show them or tell them that you were homeless and you’re a veteran, they automatically can assume stuff about you.” (WG 4)

Additionally, families in the workgroup felt that too many veteran families in their housing facility were involved with child protective services (CPS); they felt particularly discriminated against and judged for their parenting. Further, parents described previously receiving onsite services to address parenting stressors (e.g. anger management classes), that were no longer available. They recommended bringing back these services and making other programs available, such as services for alcohol or substance use problems, or for managing stress, to address family stressors and demonstrate they were working on challenges:

“… if you have problems managing stress, you are using resources just to show, yes, I am working on this….You [CPS] can’t come and say I’m not doing this to better my life with my children….” (WG 4)

Despite these concerns, parents felt it was important to share their strengths:

“…if I can spread the word to let people know that there is military in your community and you have to accept us regardless of how crazy we may be. We’re still human beings….We did something that no one else has done.” (WG 3)

3.5.2 |. Housing experience: Need for a ‘waterfall’ of help

Parents and providers expressed that parents continued to need supports, including case management, advocacy, employment, childcare, transportation, and assistance moving forward after housing. Parents and providers described supports paradoxically lessening upon receiving permanent housing (compared to when parents were homeless), which they viewed as a critical time of need. One parent illustrated the level of resources needed:

“It has to be like a waterfall of helping with issues when it comes down to our kids…It just needs to be an onslaught of help that’s going to really get us back on track, to where we need to be at in life and in society.” (WG 2)

Parents felt that an advocate or liaison – someone who understood the issues they were facing and could interface with community institutions, particularly schools – could be helpful:

“If you could introduce yourselves to the schools and be like, ‘hey, these are families that some of them are going through some tough things’.” (WG 4)

Providers confirmed this concern for ongoing supports. One provider who worked with families receiving transitional and permanent supportive housing services and followed up with families after obtaining housing, described a need for more robust ‘aftercare case management’ including following families after they obtained permanent housing and focusing on case management, mental health and life skills (Provider 7). This provider also recommended connecting families to a family peer mentoring program:

“...why don’t you adopt the family in for the summer…”.

Although providers felt that community integration was important, they often did not have the resources to help veteran parents in this process. For example, one provider wanted a vehicle to transport families to mental health or social services in the community, yet was told this was not part of the job duties.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Veteran parents experienced challenges throughout the stages of the community integration process. Our findings provide implications for facilitating community integration among veteran families through Wong and Solomon’s (2002) dimensions of community integration: (a) Social, (b) Physical, and (c) Psychological.

4.1 |. Social

Parents described the community integration process as long and tenuous, with families sequestering in their homes. Although there is little described about this adjustment period for veteran families, this echoes findings from non-veterans after receiving housing, including isolating due to exploitation concerns, worries about trust, and avoiding negative relationships (Henwood et al., 2015). After living in crowded transitional housing settings, and being in ‘survival mode,’ many families seemed to need time to decompress on their own, enjoy their surroundings and become used to a permanent setting. The experience is similar in some ways to the reintegration process of non-homeless veterans and their spouses post-deployment as they learn to cope with their ‘new normal’ (Freytes et al., 2017). Others have described homeless-experienced individuals preferring solitude to having to deal with people, especially those previously living in crowded settings (Piat et al., 2018). Some participants interviewed attributed this isolation to fear about re-traumatisation, especially among mothers with MST. This is not surprising given rates of trauma among homeless veterans (Washington et al., 2010) and concerns about trusting others after the betrayals of trust that many homeless women experience (Padgett et al., 2006). Individuals with substance use histories living in supportive housing demonstrated similar patterns of isolation related to fear from past trauma (Raphael-Greenfield & Gutman, 2015). Yet, this isolation is concerning given the prominent role that social connection plays in well-being for families (McPherson et al., 2014; Putnam, 2000).

Following the stage of isolation, families described new challenges but reduced support. Previous research demonstrates staff feeling limited in addressing community integration and needing more resources to address the longer-term needs of veterans, and among civilians, more resources needed to help parents integrate (Chinchilla, Gabrielian, Glasmeier, et al., 2019; Tischler, 2008). Our findings indicated that some providers may not be adequately trained or empowered with resources to address community integration. They may not be aware of the unique needs that families described, such as advocating in schools, particularly if getting newly acquainted with families in supportive housing. This could be addressed by training homeless service providers on community integration needs voiced by veteran families exiting homelessness (e.g. working with schools, facilitating family activities, and assisting with tasks such as paying bills). Although some providers checked on families after obtaining housing, our findings validate the need for a comprehensive ‘aftercare program’ or ongoing support after obtaining housing for veteran families.

Despite the stage of isolation, parents and providers highlighted experiencing support from other recently housed veteran families. This contrasts findings from mostly male veterans in permanent supportive housing, who avoided other veterans due to concerns they were in different stages of mental health or substance use recovery (Chinchilla, Gabrielian, Glasmeier, et al., 2019). This concern did not come up among our population, which may be related to lower rates of severe mental illness and substance use disorders among homeless-experienced veteran parents (Tsai et al., 2015). Given this finding, a veteran family peer navigator model provided by the VA could help families through community integration. Peer navigators are employed for homeless-experienced individuals and veterans with mental illness and substance use (Oh & Rufener, 2017), and are associated with improvements in engagement (Corrigan, Pickett, et al., 2017), health, and quality of life (Corrigan, Sheehan, et al., 2017). Homeless-experienced veteran parents might serve as navigators to help other families build social relationships and access family activities.

4.2 |. Physical

After the stage of ‘shell shock’ many parents described the importance of linking to the community through their children (including through churches and social service offices) and offering support to neighbours with children. Women with children are known to have greater integration than women without, which is thought to be related to more opportunities for community participation (Nemiroff et al., 2011). Further, some parents expressed the centrality of children’s schools to community interactions. The US McKinney-Vento Act defines the rights of homeless students and the responsibilities schools have to them (Sulkowski & Joyce-Beaulieu, 2014). Schools could build upon their role in the community by linking recently housed veteran families to services and helping them physically integrate. Although prior findings demonstrate how to support community integration for individual adults, these findings show a critical need to structure community integration efforts around children and families in novel ways to enhance community integration of veteran families.

4.3 |. Psychological

Veteran parents often felt judged by non-veteran community members. Stigma is a noted concern among homeless-experienced individuals who are integrating into the community (Bower et al., 2018; Bromley et al., 2013). Stigma is inversely correlated to psychological integration (Prince & Prince, 2002). Veteran advocacy groups and peers could dispel misconceptions and provide education regarding veteran family experiences and strengths to address stigma. Schools could use stigma-reduction efforts to combat the feeling of judgement some parents experienced.

Additionally, CPS involvement was a source of perceived judgement. Parents were rightfully concerned; family homelessness increases the risk of out-of-home placement (Park et al., 2004), which can compound family trauma (Ijadi-Maghsoodi et al., 2019). Fear about CPS involvement and judgement of parenting can negatively impact families’ community integration and affect parents reaching out for help, leading to further isolation and stress. Families called for increased programs addressing family challenges to prevent CPS involvement. In a prior study, formerly homeless mothers also recommended parenting support (Tischler, 2008). This demonstrates a need for preventive parenting interventions and family support programs for recently housed veteran families, either delivered at the VA or community settings.

4.4 |. Limitations

Our findings had several limitations. First, the number of parents interviewed without additional permissions were limited by the Paperwork Reduction Act (1995). Nevertheless, we reached thematic saturation, and provider interviews and the workgroup validated our findings. Second, our findings only reflect the experiences of veteran parents living in housing facilities in Southern California, and not the experiences of those in less-resourced regions, those who may not volunteer to participate, and those who have not remained permanently housed. Third, our workgroup sessions may only reflect the experiences at this particular facility and city. Finally, we only involved veterans associated with the VA healthcare system; caution must be used in extrapolating these experiences to other healthcare systems, including civilians without the same housing/healthcare resources.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

Beyond identifying barriers, parents and providers voiced concrete recommendations to improve community integration that can inform programs and practices for veteran families. These include providing transportation to access community services, facilitating family activities at housing facilities to bring families together and normalise stressors after obtaining housing, offering parenting support and stress reduction, and promoting community activities (including at schools) centred around children to develop social connections. Although we identified practical recommendations, future studies should focus on predictors and long-term outcomes of community integration among homeless-experienced veteran families and interventions to facilitate community integration. Future studies should also examine the process of community integration using a gender lens, and with a larger and more varied sample size, including examining the roles of providers in more detail. Our findings suggest that providers should understand the community integration needs of veteran families exiting homelessness, and address community integration to improve well-being and housing outcomes of this important population.

What is known about this topic?

There is growing recognition of the importance of community integration when addressing homelessness.

The experience of community integration is poorly understood among homeless-experienced veteran families.

Services for homeless-experienced families often do not focus on supporting community integration after obtaining permanent housing.

What this paper adds?

Interviews with homeless-experienced veteran parents and service providers revealed that veteran families would often initially isolate in their homes after obtaining permanent housing, followed by grappling with new challenges and fears about losing housing.

Although parents described feeling supported by other homeless-experienced veteran families, they often felt judged and misunderstood by civilians in the community.

Veteran families need ongoing advocacy, case management and support after obtaining permanent housing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health or the United States Government. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Nicholas Brown for his help in conducting the qualitative analysis. We are so appreciative of the parents and providers for sharing their valuable time and important insights with us.

Funding information

This work was supported by a locally initiated project award (LIP-65-160) from the HSR&D Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation & Policy at the Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and a Greater Los Angeles Veteran Affairs Research Enhancement Award Program (REAP). Dr. Ijadi-Maghsoodi was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations through the VA Advanced Fellowship in Women’s Health during this work. Dr. Ijadi-Maghsoodi receives funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K12DA000357 and the Greater Los Angeles VA UCLA Center of Excellence for Veteran Resilience and Recovery. Dr. Moore is funded by the National Clinician Scholars Program at the Greater Los Angeles VA and the UCLA Department of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research. Dr. Cohenmehr was supported by the Dean’s Leadership in Health and Science Scholarship at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine. She was supported by the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and the Community Health Sciences Department through a summer internship during this work.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Author elects not to share data: These findings are from qualitative data; while de-identified, the nature of the data does not ensure complete anonymity for participants. Participants did not give permission for their data to be available publicly for other studies to use.

REFERENCES

- ATLAS.ti. (2013). ATLAS.ti (Version 7.1) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://atlasti.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Austin EL, Pollio DE, Holmes S, Schumacher J, White B, Lukas CV, & Kertesz S. (2014). VA’s expansion of supportive housing: Successes and challenges on the path toward Housing First. Psychiatric Services, 65(5), 641–647. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, DeCandia CJ, Tsertsvadze A, & Richard MK. (2014). The effectiveness of housing interventions and housing and service interventions on ending family homelessness: A systematic review. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(5), 457–474. 10.1037/ort0000020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GA. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137–152. 10.1177/1468794107085301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bower M, Conroy E, & Perz J. (2018). Australian homeless persons’ experiences of social connectedness, isolation and loneliness. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(2), e241–e248. 10.1111/hsc.12505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley E, Gabrielian S, Brekke B, Pahwa R, Daly KA, Brekke JS, & Braslow JT. (2013). Experiencing community: Perspectives of individuals diagnosed as having serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 64(7), 672–679. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla M, Gabrielian S, Glasmeier A, & Green MF. (2019). Exploring community integration among formerly homeless veterans in project-based versus tenant-based supportive housing. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(2), 303–312. 10.1007/s10597-019-00473-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla M, Gabrielian S, Hellemann G, Glasmeier A, & Green M. (2019). Determinants of community integration among formerly homeless veterans who received supportive housing. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 472. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Pickett S, Schmidt A, Stellon E, Hantke E, Kraus D, Dubke R; Community Based Participatory Research Team. (2017). Peer navigators to promote engagement of homeless African Americans with serious mental illness in primary care. Psychiatry Research, 255, 101–103. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, Sheehan L, Morris S, Larson JE, Torres A, Lara JL, Paniagua D, Mayes JI, & Doing S. (2017). The impact of a peer navigator program in addressing the health needs of Latinos with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 69(4), 456–461. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnitsky CA, & Kilmer RP. (2017). Facilitating reintegration for military service personnel, veterans, and their families: An introduction to the special issue. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(2), 109. 10.1037/ort0000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WN, Kroeger S, Palmer C, & Pohl E. (2019). Housing and urban development–Veterans Affairs supportive housing vouchers and veterans’ homelessness, 2007–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1440–1445. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freytes IM, LeLaurin JH, Zickmund SL, Resende RD, & Uphold CR. (2017). Exploring the post-deployment reintegration experiences of veterans with PTSD and their significant others. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(2), 149–156. 10.1037/ort0000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielian S, Young AS, Greenberg JM, & Bromley E. (2018). Social support and housing transitions among homeless adults with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41(3), 208. 10.1037/prj0000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MA, Zonneville M, & Bassuk E. (2013). The SHIFT study: Final report. American Institute for Research. Retrieved from https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/SHIFT_Service_and_Housing_Interventions_for_Families_in_Transition_final_report.pdf

- Henwood BF, Stefancic A, Petering R, Schreiber S, Abrams C, & Padgett DK. (2015). Social relationships of dually diagnosed homeless adults following enrollment in housing first or traditional treatment services. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 6(3), 385–406. 10.1086/682583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Quan M, Horton J, Ryan GW, Kataoka S, Lester P, Milburn NG, & Gelberg L. (2019). Youth growing up in families experiencing parental substance use disorders and homelessness: A high-risk population. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 29(10), 773–782. 10.1089/cap.2019.0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker AE (Eds.). (2005). Methods in community- based participatory research for health. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, & Wells K. (2007). Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(4), 407–410. 10.1001/jama.297.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl MA, Davies D, Carlson P, Johnston J, & Minnes P. (2001). The community integration measure: Development and preliminary validation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82(4), 429–434. 10.1053/apmr.2001.22195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson KE, Kerr S, McGee E, Morgan A, Cheater FM, McLean J, & Egan J. (2014). The association between social capital and mental health and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: An integrative systematic review. BMC Psychology, 2(1), 7. 10.1186/2050-7283-2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excel Microsoft. (2016). Computer Software Retrieved from https://office.microsoft.com/excel

- Nemiroff R, Aubry T, & Klodawsky F. (2011). From homelessness to community: Psychological integration of women who have experienced homelessness. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(8), 1003–1018. 10.1002/jcop.20486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, & Rufener C. (2017). Veteran peer support: What are the mechanisms? Psychiatric Services, 68(4), 424. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Hawkins RL, Abrams C, & Davis A. (2006). In their own words: Trauma and substance abuse in the lives of formerly homeless women with serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(4), 461–467. 10.1037/1040-3590.76.4.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paperwork Reduction Act. (1995). 5 C.F.R. § 1320.

- Paquette K, & Bassuk EL. (2009). Parenting and homelessness: Overview and introduction to the special section. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(3), 292–298. 10.1037/a0017245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Metraux S, Broadbar G, & Culhane DP. (2004). Child welfare involvement among children in homeless families. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 83(5), 423–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piat M, Sabetti J, & Padgett D. (2018). Supported housing for adults with psychiatric disabilities: How tenants confront the problem of loneliness. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(2), 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince PN, & Prince CR. (2002). Perceived stigma and community integration among clients of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(4), 323. 10.1037/h0095005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael-Greenfield EI, & Gutman SA. (2015). Understanding the lived experience of formerly homeless adults as they transition to supportive housing. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 31(1), 35–49. 10.1080/0164212X.2014.1001011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Brown SR, & Gubits D. (2017). Can housing and service interventions reduce family separations for families who experience homelessness? American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(1–2), 79–90. 10.1002/ajcp.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverbush M, Kuhn J, & Southcott L. (2017). FY 2017 annual report Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/homeless/ssvf/docs/SSVF_FY2017_AnnualReport_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski ML, & Joyce-Beaulieu DK. (2014). School-based service delivery for homeless students: Relevant laws and overcoming access barriers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 711. 10.1037/ort0000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischler V. (2008). Resettlement and reintegration: Single mothers’ reflections after homelessness. Community, Work & Family, 11(3), 243–252. 10.1080/13668800802133628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Mares AS, & Rosenheck RA. (2012). Does housing chronically homeless adults lead to social integration? Psychiatric Services, 63(5), 427–434. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Rosenheck RA, Kasprow WJ, & Kane V. (2015). Characteristics and use of services among literally homeless and unstably housed US veterans with custody of minor children. Psychiatric Services, 66(10), 1083–1090. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. (2020). The 2019 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2019-AHAR-Part-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Washington DL, Yano EM, McGuire J, Hines V, Lee M, & Gelberg L. (2010). Risk factors for homelessness among women veterans. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(1), 82–91. 10.1353/hpu.0.0237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J, Fossey E, & Harvey C. (2019). A home but how to connect with others? A qualitative meta-synthesis of experiences of people with mental illness living in supported housing. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(3), 546–564. 10.1111/hsc.12615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YLI, & Solomon PL. (2002). Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: A conceptual model and methodological considerations. Mental Health Services Research, 4(1), 13–28. 10.1023/a:1014093008857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Barrow SM, & Tsemberis S. (2004). Community integration in the early phase of housing among homeless persons diagnosed with severe mental illness: Successes and challenges. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(2), 133–150. 10.1023/B:COMH.0000022733.12858.cb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabkiewicz DM, Patterson M, & Wright A. (2014). A cross-sectional examination of the mental health of homeless mothers: Does the relationship between mothering and mental health vary by duration of homelessness? British Medical Journal Open, 4(12), e006174. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Author elects not to share data: These findings are from qualitative data; while de-identified, the nature of the data does not ensure complete anonymity for participants. Participants did not give permission for their data to be available publicly for other studies to use.