Abstract

Sacbrood virus (SBV) infects larvae of the honeybee (Apis mellifera), resulting in failure to pupate and death. Until now, identification of viruses in honeybee infections has been based on traditional methods such as electron microscopy, immunodiffusion, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Culture cannot be used because no honeybee cell lines are available. These techniques are low in sensitivity and specificity. However, the complete nucleotide sequence of SBV has recently been determined, and with these data, we now report a reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) test for the direct, rapid, and sensitive detection of these viruses. RT-PCR was used to target five different areas of the SBV genome using infected honeybees and larvae originating from geographically distinct regions. The RT-PCR assay proved to be a rapid, specific, and sensitive diagnostic tool for the direct detection of SBV nucleic acid in samples of infected honeybees and brood regardless of geographic origin. The amplification products were sequenced, and phylogenetic analysis suggested the existence of at least three distinct genotypes of SBV.

Sacbrood is a condition affecting the brood of the honeybee, resulting in larval death. Larvae with sacbrood fail to pupate, and ecdysial fluid, rich in sacbrood virus (SBV), accumulates beneath their unshed skin, forming the sac for which the condition is named. Infected larvae change in color from pearly white to pale yellow, and shortly after death they dry out, forming a dark brown gondola-shaped scale 5. SBV may also affect the adult bee, but in this case obvious signs of disease are lacking 2, 4. Such bees may, however, have a decreased life span 4, 7, 15. Sacbrood occurs most frequently in spring, when the colony is growing most rapidly and large numbers of susceptible larvae and young adults are available 4.

Although sacbrood was first described in 1913 and was attributed to virus infection in 1917 16, the causative agent itself, SBV, was not characterized until 1964 9. SBV is one of many insect viruses generally referred to as picornavirus-like. This presumed similarity has been based largely on biophysical properties and the presence of an RNA genome 13; SBV particles are 28 nm in diameter, nonenveloped, round, and featureless in appearance 3, 10. The genomic RNA resembles that of rhinoviruses in base composition (G + C = 37 to 39%), and the virus is acid labile 6, 12, 14. Three structural proteins (25, 28, and 31.5 kDa) have been reported in SBV 6, 8. A small VP4-like protein has not been detected 11. SBV is the first honeybee virus to be completely sequenced; the genomic RNA is longer (8,832 nucleotides [nt]) than that of typical mammalian picornaviruses (approximately 7,500 nt) and contains a single, large open reading frame (nt 179 to 8752) encoding a polyprotein of 2,858 amino acids. The genomic organization of SBV clearly resembles that of typical members of the Picornaviridae, with structural genes at the 5′ end and nonstructural genes at the 3′ end arranged in a similar order. Sequence comparison suggested that SBV is distantly related to infectious flacherie virus of the silkworm, a virus that possesses a genome of similar size and gene order 11.

The role of viruses in honeybee pathogenesis is of increasing concern; recent evidence shows that virus-induced disease can be exacerbated and persistent infections activated by infestation with the parasitic mite Varroadestructor, and the incidence of mite infestation is also rising. Furthermore, the consequences of virus infections are becoming more significant, since infections today have repercussions beyond their direct impact on honey production. Environmental pollution has dramatically reduced (or even eradicated) the populations of many insect species, and the role of bees as essential pollinators for plants has become paramount. Virus-induced population decrease among honeybees thus affects not only the bee-farming economy but also other aspects of agriculture (especially fruit production) and plant ecology. Consequently, it is surprising that these agents have not been studied and so little is known about their molecular biology.

Until now, laboratory diagnosis of honeybee viruses was based on electron microscopic identification of the virus particles and traditional methods of antigen detection such as immunodiffusion assays, radioimmunoassay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Most of these assays show low sensitivity and specificity or exhibit nonspecific reactions 1; also, differentiation between virus types is difficult or impossible by such conventional methods. Diagnosis and further study are also complicated, since there are no honeybee cell lines and viruses cannot be isolated and propagated in vitro. One goal of our study was therefore to establish a sensitive molecular method to detect SBV directly in samples of diseased honeybees and their brood. From the published complete nucleotide sequence of SBV 11, we developed five different reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assays specific for SBV, each amplifying a different region of the SBV genome. The amplicons were sequenced without subcloning, and the sequences were compared. Phylogenetic trees were constructed to examine the genetic relatedness of SBV specimens from different geographic regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

Infected honeybees and larvae used in this study (16 different samples) originated from various geographic regions: mainland Europe (Austria and Germany), the United Kingdom, India, Nepal, and South Africa. They were collected from sacbrood outbreaks between 1996 and 1999 and sent to us by collaborating colleagues. The samples had been diagnosed as SBV infected based on disease symptoms and confirmed by immunodiffusion test or ELISA. As negative controls, samples were included which were free of any detectable virus. To assess specificity, samples which were infected with other picornavirus-like honeybee viruses, such as acute bee paralysis virus or black queen cell virus, were also tested. The samples were stored frozen at −80°C until analyzed.

Isolation of RNA.

SBV-infected bees and larvae as well as control samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen, diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water was added, and the suspension was centrifuged at 1,700 × g for 5 min. Then 140 μl of the supernatant was used for RNA extraction, employing the QIAmp viral RNA purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Primer design.

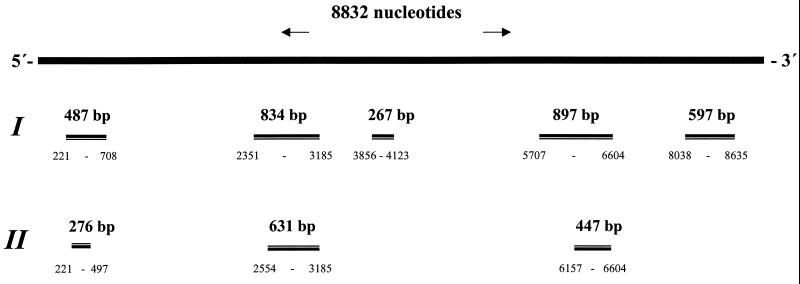

Five pairs of oligonucleotide primers were selected from the published SBV-UK genome 11 using the Primer Designer program (Scientific & Educational Software, version 3.0). The primers were chosen to target different regions of the genome in order to obtain sequence information from conserved as well as more variable regions. For three of these primer pairs, internal primers were also designed in order to perform seminested PCR. The sequences, orientations, and locations of these oligonucleotide primers are given in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Nucleotide positions refer to the SBV-UK sequence (GenBank accession no. AF092924).

TABLE 1.

Primers selected for SBV RT-PCR and seminested PCR

| Primera | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Nucleotide positionsb | Amplified product length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SB1 f | ACC AAC CGA TTC CTC AGT AG | 221–240 | 487 |

| SB2 r | CCT TGG AAC TCT GCT GTG TA | 689–708 | |

| SB3 r, s-n | TCT TCG TCC ACT CTC ATC AC | 478–497 | 276 |

| SB6 f | GTG GCA GTG TCA GAT AAT CC | 2351–2370 | 834 |

| SB7 r | GTC AGA GAA TGC GTA GTT CC | 3166–3185 | |

| SB8 f, s-n | GCG TAG ACC AGT GTT GTT GT | 2554–2573 | 631 |

| SB9 f | ACC GTT GTC TGG AGG TAG TT | 3856–3875 | 267 |

| SB10 r | GCC GCA TTA GCT TCT GTA GT | 4104–4123 | |

| SB11 f | ATA TAC GGT GCG AGA ACT GC | 5707–5726 | 897 |

| SB12 r | CTC GGT AAT AAC GCC ACT GT | 6585–6604 | |

| SB13 f, s-n | CTG GAT GAG AGC GAA TGA AG | 6157–6176 | 447 |

| SB14 f | AAT GGT GCG GTG GAC TAT GG | 8038–8057 | 597 |

| SB15 r | TGA TAC AGA GCG GCT CGA CA | 8616–8635 |

FIG. 1.

Locations of the amplified PCR products within the SBV genome. (I) RT-PCR products amplified with primer pairs SB1-SB2, SB6-SB7, SB9-SB10, SB11-SB12, and SB14-SB15. (II) Seminested PCR products.

RT-PCR.

SBV RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA, and five regions of the genome were amplified by using a continuous RT-PCR method, in which reverse transcription and DNA amplification take place in one uninterrupted reaction (one-tube assay). We used a reaction volume of 50 μl and tested three different RT-PCR kits in parallel: the Titan one-tube RT-PCR system (Roche Diagnostics), the Access RT-PCR system (Promega), and the Qiagen one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). The PCR assays were carried out according to the manufacturers' recommendations. The Access RT-PCR system (Promega), which allows variable Mg2+ concentrations, was optimized in this respect; an Mg2+ concentration of 1 mM proved best. Besides the controls mentioned above, negative controls lacking RNA or DNA template were also included in every run (including seminested analysis). All amplifications were performed in GeneAmp PCR System 2400 thermal cyclers (Perkin Elmer). In all cases, 40 rounds of amplification were carried out.

Seminested PCR.

Any samples that failed to yield a product on first-round PCR were also analyzed in seminested PCR. This was performed using 3 μl of the first-round PCR assay mixtures and the appropriate primers (Table 1). The 50-μl reaction mixtures contained 35 μl of RNase-free water, 5 μl of 10× RT-PCR buffer with Mg2+ (1.5 mM MgCl2 final concentration) (Perkin Elmer), 4 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix (10 mM each), 1 μl of the forward primer (40 pmol), 1 μl of the reverse primer (40 pmol), 1 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide, and 0.25 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega; 1.25 U, final concentration) in storage buffer B. This reaction mixture was subjected to 40 cycles with an initial incubation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by heat denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, primer annealing at 55°C for 20 s, and DNA extension at 72°C for 1 min. Thereafter, the samples were maintained at 72°C for 7 min for the final extension. To avoid possible amplicon carryover, special precautions were taken when performing seminested PCR. These precautions included the use of the NCC (non-cross contamination) system from MWG Biotech, consisting of special PCR tubes and unique openers which were designed to minimize possible contaminations. Also, seminested PCR was carried out in a separate room on a different floor with completely separate equipment.

Gel electrophoresis.

The PCR products (20 μl) were electrophoresed in a 1.2% Tris acetate-EDTA–agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Bands were photographed in an Eagle Eye II UV gel imaging system (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Fragment sizes were determined with reference to a 100-bp ladder (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Nucleotide sequencing and computer analyses.

The PCR products amplified by the Qiagen one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) were excised from the gel and extracted using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence-based sequencing PCR was performed employing the ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin Elmer) with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, including all the required components for the sequencing reaction except the primers. The primers used for the sequencing PCR were identical to those employed in the RT-PCR stage but at a concentration of 4 pmol. The reaction mixture consisted of 4 μl of Big Dye Terminator Ready Reaction Mix, 1 μl of primer (4 pmol), 5 to 15 μl of gel-extracted DNA, and distilled water to a final volume of 20 μl. The thermal profile for the sequencing PCR was 96°C for 30 s (denaturation), 50°C for 10 s (primer annealing), and 60°C for 4 min (primer extension). After 30 cycles, the PCR products obtained were purified by precipitating the DNA with 70% ethanol solution containing 0.5 mM MgCl2, incubating the mixture at room temperature for 10 min, centrifuging at 16,060 × g for 25 min (also at room temperature), and, after discarding the supernatant, adding the ABI Prism template suppression reagent denaturing buffer (Perkin Elmer). Finally, shortly before the samples were put into the sequencer, they were boiled for 2 min and then placed rapidly on ice. All PCR products were sequenced in both directions by the automatic sequencing system ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin Elmer).

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were compiled and aligned using the Align Plus program (Scientific & Educational Software, version 3.0, serial no. 43071) and verified by visual inspection. Genetic relatedness between SBV samples was performed by phylogenetic tree construction using the programs contained in the Phylogeny Inference package (PHYLIP) (version 3.57c). The reliability of the trees was tested by bootstrap resampling analysis of 100 replicates generated with the SEQBOOT program of the PHYLIP package. Distance matrices were computed using the DNADIST/neighbor-joining program (PHYLIP package), choosing a transition/transversion ratio of 2.0.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences described in this paper were submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers AF284616 to AF284644 and AF284648 to AF284691.

RESULTS

Analysis of sacbrood specimens by RT-PCR.

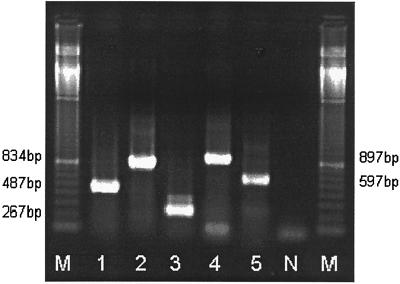

The aim of this study was to establish a rapid and sensitive molecular method to detect SBV in samples of infected honeybees and brood. Five pairs of SBV-specific primers were designed (Table 1), amplifying different regions of the genome (Fig. 1), based on the only available SBV nucleotide sequence, which has been derived from a natural outbreak of sacbrood in the United Kingdom 11 (GenBank accession no. AF092924). A total of 16 different samples of SBV-infected honeybees and brood from Austria, Germany, the United Kingdom, India, Nepal, and South Africa were received. They were collected between 1996 and 1999 and stored frozen until processed. With very few exceptions, the samples tested positive in all five RT-PCR assays developed and with all RT-PCR kits tested. PCR products of the expected sizes were observed as clear electrophoretic bands (Fig. 2). Amplification products were never detected in the negative controls.

FIG. 2.

Detection of SBV in honeybees and brood by RT-PCR assays amplifying five different regions (lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) of the SBV genome. The amplification products were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. Lanes M, DNA size markers (100-bp ladder); lane N, negative control.

In general, all three RT-PCR kits employed in our study performed similarly well. With a few exceptions, the Titan one-tube RT-PCR system (Roche Diagnostics) and the Access RT-PCR system (Promega) resulted in reproducibly high levels of PCR products. Although all of the SBV-specific primers were successful in some or all reactions, we optimized the reactions obtained by the Access RT-PCR system for magnesium ion concentration and annealing temperature in order to reduce nonspecific amplification and increase product yield; the best results were achieved with a final magnesium concentration of 1 mM, an annealing temperature of 55°C, and 40 cycles of iteration. Compared to the above two RT-PCR systems, the Qiagen one-step RT-PCR kit, which includes a hot-start DNA polymerase and is designed for highly efficient and specific RT-PCR, proved to be superior. With this system, all samples tested were already positive in the first-round PCR with high yields of product, while with the other two kits a few samples resulted in an insufficient amount of PCR product or were even negative after first-round PCR but proved positive by subsequent seminested PCR.

Sequence analysis and comparison.

The amplicons were identified as SBV by sequencing and Blast search against the database. In total, 73 RT-PCR products were characterized: 14 derived from primer pair SB1-SB2, 15 from primer pair SB6-SB7, 15 from SB9-SB10, 13 from SB11-SB12, and 16 from primer pair SB14-SB15. In total, the sequences derived from the five PCR target regions covered 37.7% of the SBV genome. After sequencing, it was possible to align 2,767 nt from each sample covering 31.3% of the total SBV genome. Sequence similarity between these SBV sequences was determined with the Align Plus program using the published sequence 11 as a reference. Figures 3 to 10 present the results of this analysis and show all the nucleotide alignments (plus selected amino acid alignments) for each region and percent identity. Phylogenetic trees were constructed, and tree reliability was tested by bootstrap analysis of 100 replicates. All five genomic regions analyzed yielded highly similar trees; a typical example is presented in Fig. 11.

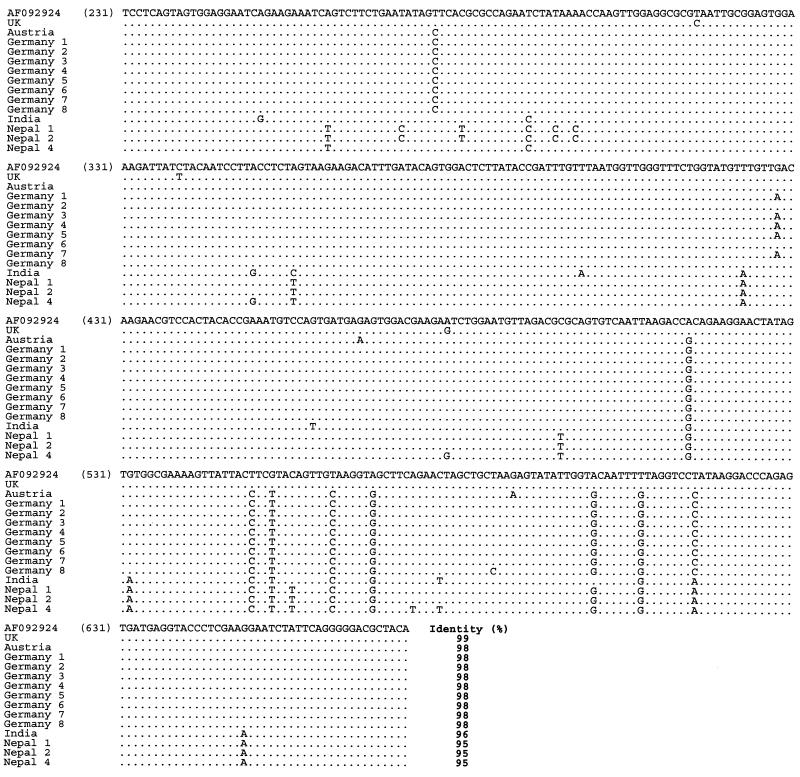

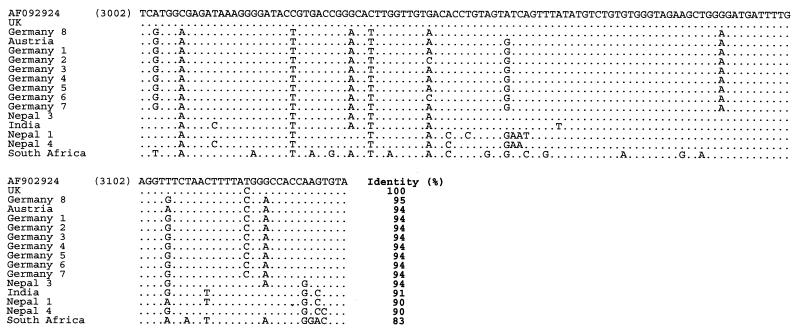

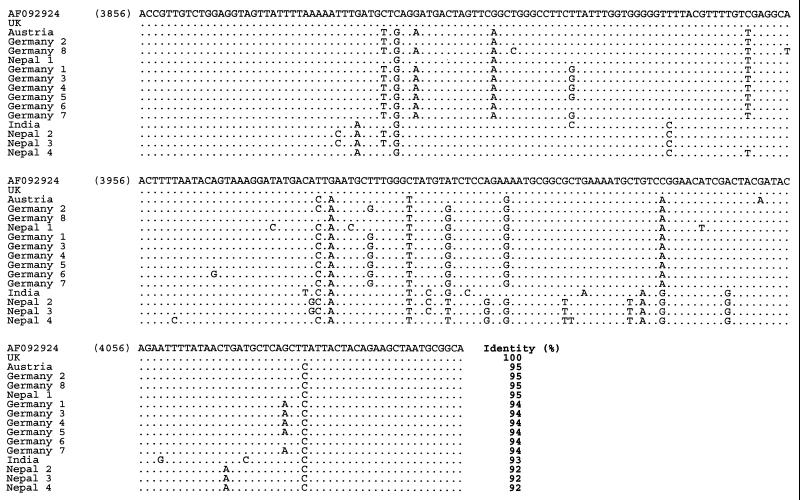

FIG. 3.

Multiple alignment of the nucleotide sequences of SBV samples from various geographic regions obtained with primer pair SB1-SB2 (nucleotide positions 231 to 673 according to reference strain AF092924). The sequences obtained with this primer pair have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AF284616 to AF284629.

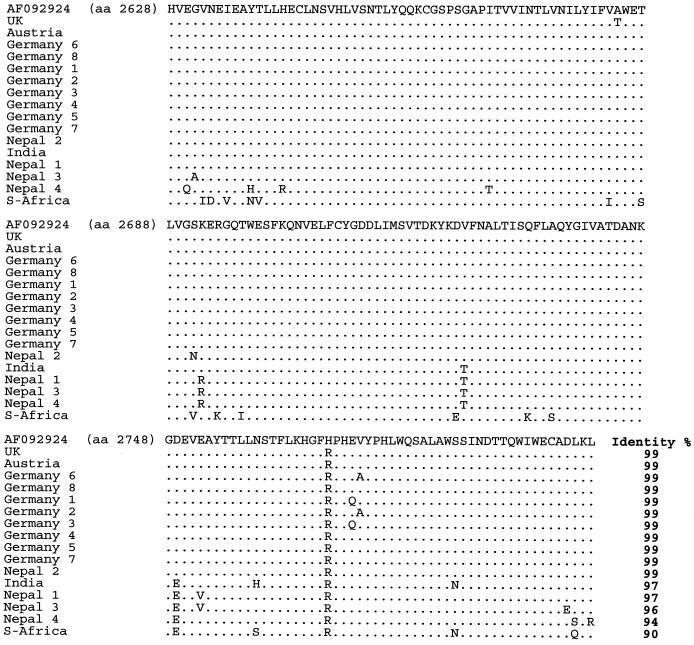

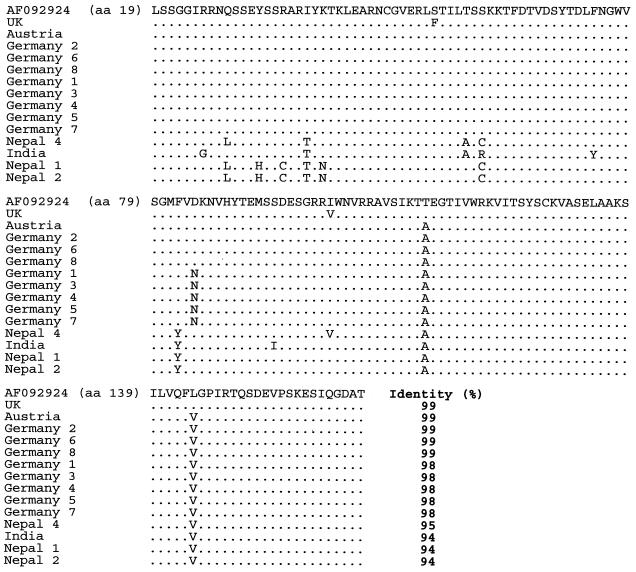

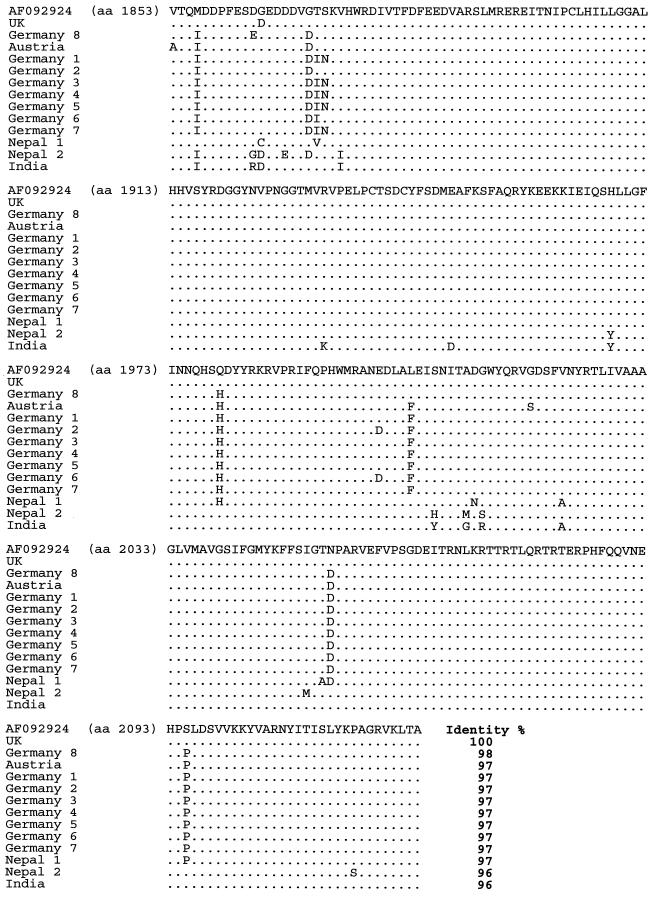

FIG. 10.

Multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences obtained with primer pair SB14-SB15 (amino acid positions 2628 to 2801 according to reference strain AF092924).

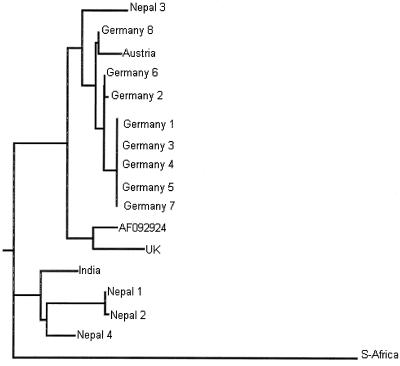

FIG. 11.

Phylogenetic tree illustrating the genetic relationship among SBV strains generated by the DNADIST/neighbor-joining program; the South African sample was used as an outgroup.

At least three distinct genetic lineages of SBV could be identified: a European genotype (with Central European and British subtypes), a Far Eastern genotype representing the Thai SBVs and consisting of strains from India and Nepal, and a distinct third genotype originating from South Africa. The Central European subtype includes strains from Austria and Germany, while the British subtype consists of the prototype strain AF092924 (SBV-UK; GenBank) and another isolate from the United Kingdom.

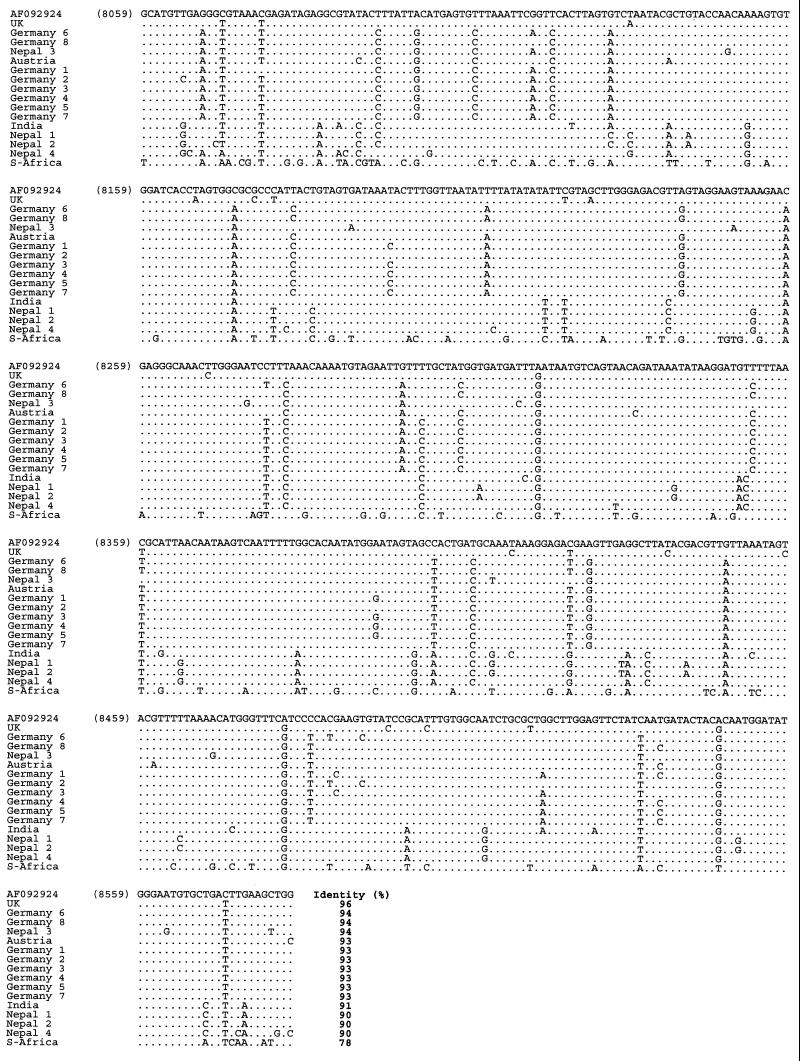

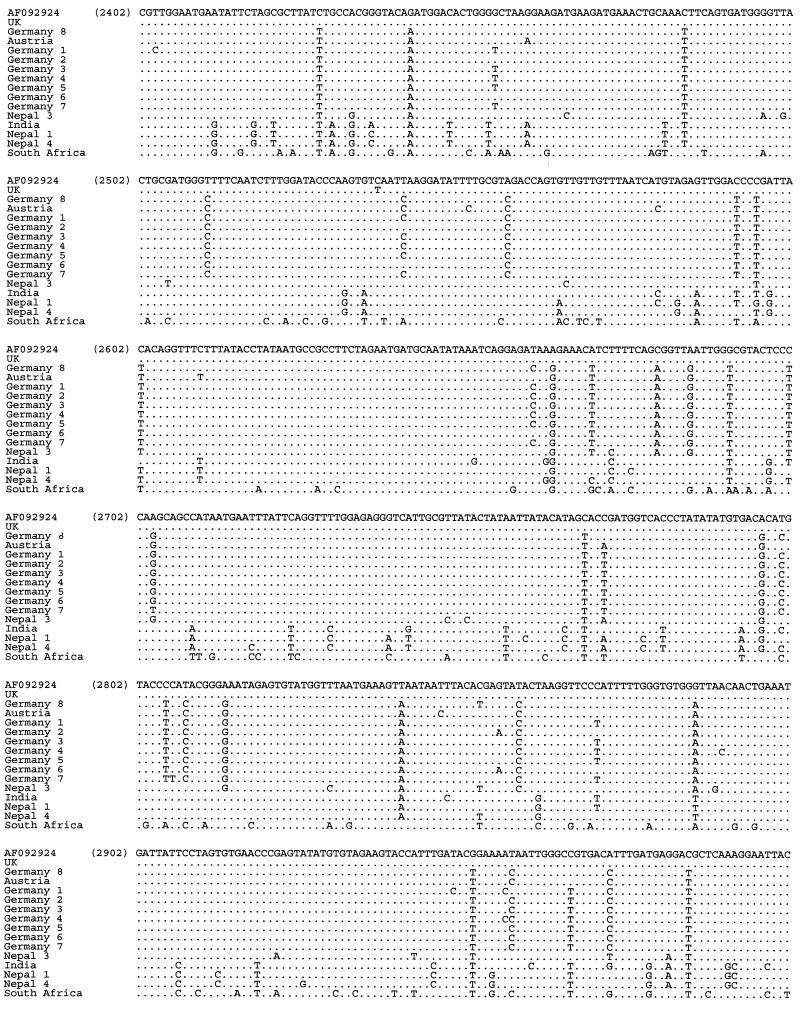

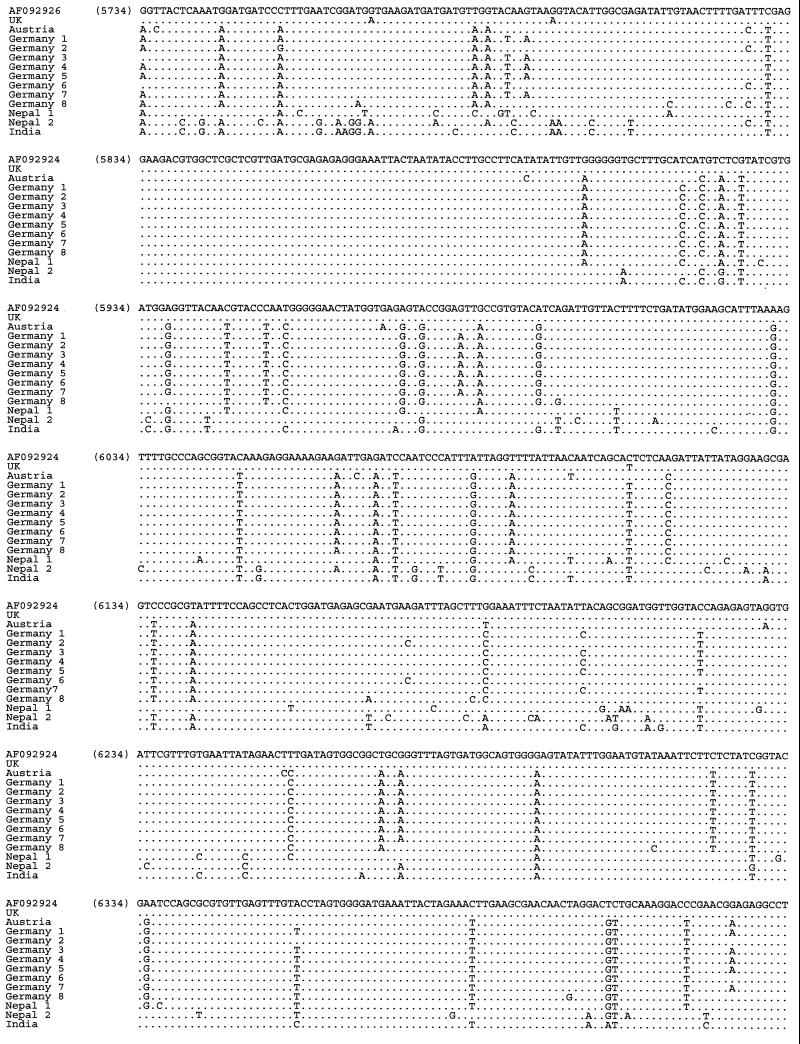

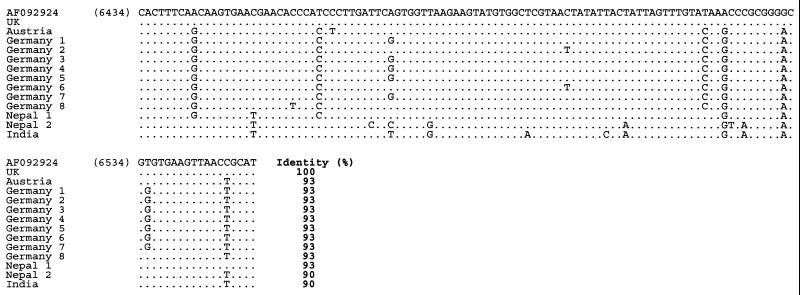

Nucleotide sequence identities ranged from 78 to 100%. The highest homology (95 to 100%) was found close to the 5′ end of the genome, especially in the region amplified with primers SB1 and SB2 (nt 221 to 708). The greatest divergence was observed near the 3′ end (SB14 and SB15; nt 8059 to 8582). Identity decreased to 78% in this region (e.g., comparing the South African SBV sequence with the British SBV-UK reference sequence). This observation held true not only between the three proposed genotypes but also within the genotypes, although in these cases the degree of variation was lower. The amino acid variability among the samples was similar to the variability at the nucleotide level, and phylogenetic trees based on amino acid sequences showed branches identical to those in the nucleotide-based trees.

The European strains formed a homogeneous cluster, with nucleotide sequence identity rates ranging between 93 and 100%. The degree of amino acid variability was 0 to 3% within this genotype. The British strain (British subtype) showed the highest sequence homologies (96 to 100%) with the reference sequence, which is not surprising, because both strains were obtained from the United Kingdom. European strains were well conserved, and only a few changes in sequence were noted; German strains differed by 0 to 2% from each other, and a similar extent of divergence was seen between German and Austrian strains (1%). However, the Austrian SBV sequence was altered at different positions from those which varied between German strains.

In a similar fashion, the Far Eastern viruses were well conserved within the cluster (0 to 3% divergence), although the degree of variation between the Indian and Nepalese strains (1 to 3%) can clearly be seen in the alignment (Fig. 3 to 7). However, distinct sequence variation was noted between the European and Far Eastern genotypes not only at the nucleotide level (up to 10%), but also at the amino acid level (up to 6%). The extent of this difference is sufficient to support the existence of two distinct genogroups and is clearly visible in the phylogenetic trees (Fig. 11).

FIG. 7.

Multiple alignment of the nucleotide sequences of SBV samples from various geographic regions obtained with primer pair SB14-SB15 (nucleotide positions 8059 to 8582 according to reference strain AF092924). The sequences obtained with this primer pair have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF284676 to AF284691.

The South African SBV differed remarkably from both European genotype viruses (11 to 22%) and also from the Far Eastern genotype viruses (7 to 13%) at the nucleotide level. Striking divergence was also present at the amino acid level, although the degree of variation was lower, between 2 and 10% for the European-type SBVs and between 1 and 7% for the Far Eastern-type viruses. Due to the high divergence of this single SBV from South Africa compared to the other two types (see also the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 11), we propose that a third SBV genotype may exist, although additional samples from South Africa have to be analyzed to confirm this conclusion.

DISCUSSION

Although the condition sacbrood was described at the beginning of the 20th century and attributed to a virus infection 16, the causative agent itself, SBV, was not characterized until 1964 9. Most of the honeybee viruses detected to date are picornavirus-like positive-stranded RNA viruses. While classical characterization of these viruses has been carried out, only very limited information is available at the molecular level. SBV was the first virus of the honeybee for which the genome organization and complete nucleotide sequence were determined 11. On the other hand, nothing is known so far regarding the variability of this virus in samples collected from outbreaks in different locations. We have shown that there are potentially three distinct groupings of SBV around the world. However, this may not simply reflect geographic isolation: the Far Eastern type includes strains from India and Nepal, and in this location sacbrood is an important disease of the eastern honeybee, Apis cerana, causing severe clinical symptoms in this host. The European honeybee, Apis mellifera, seems to be rather resistant to this SBV type. This suggests that some of the differences detected here may result from adaptation to a different host rather than from simple geographic clustering. In this regard we note that one of the Nepalese samples (Nepal 3) grouped closely with the European genotype (Fig. 11). Indeed, this virus originated from a Nepalese SBV-infected A. mellifera and not from A. cerana. Thus, both genotypes of virus seem to be present in Nepal but induce disease in different species. More detailed investigation will be required to resolve this question and eventually to allow us to interpret the significance of differences in genome sequence to virus biology.

All five RT-PCR procedures described here could be used in principle for further phylogenetic analyses; however, primer pairs SB1-SB2, SB6-SB7, and SB14-SB15 proved to be the most useful and amplified all SBV types equally well. The first two pairs seem to reveal the greatest conservation between strains, while the last should be more useful for investigations of divergence. We therefore suggest the use of these two RT-PCR assays for diagnostic purposes.

FIG. 4.

Multiple alignment of the nucleotide sequences of SBV samples from various geographic regions obtained with primer pair SB6-SB7 (nucleotide positions 2402 to 3133 according to reference strain AF092924). The sequences obtained with this primer pair have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF284630 to AF284644.

FIG. 5.

Multiple alignment of the nucleotide sequences of SBV samples from various geographic regions obtained with primer pair SB9-SB10 (nucleotide positions 3856 to 4105 according to reference strain AF092924). The sequences obtained with this primer pair have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF284661 to AF284675.

FIG. 6.

Multiple alignment of the nucleotide sequences of SBV samples from various geographic regions obtained with primer pair SB11-SB12 (nucleotide positions 5734 to 6551 according to reference strain AF092924). The sequences obtained with this primer pair have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF284648 to AF284660.

FIG. 8.

Multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences obtained with primer pair SB1-SB2 (amino acid positions 19 to 165 according to reference strain AF092924).

FIG. 9.

Multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences obtained with primer pair SB11-SB12 (amino acid positions 1853 to 2124 according to reference strain AF092924).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson D L. A comparison of serological techniques for detecting and identifying honeybee viruses. J Invertebr Pathol. 1984;44:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D L, Gibbs A J. Transpuparial transmission of Kashmir bee virus and sacbrood virus in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) Ann Appl Biol. 1989;114:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey L. Honey bee pathology. Annu Rev Entomol. 1968;13:191–212. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey L. The multiplication and spread of sacbrood virus of bees. Ann Appl Biol. 1969;63:483–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1969.tb02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey L. Recent research on honey bee viruses. Bee World. 1975;56:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey L. Viruses attacking the honey bee. Adv Virus Res. 1976;20:271–304. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey L, Fernando E F W. Effects of sacbrood virus on adult honey bees. Ann Appl Biol. 1972;72:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey L, Carpenter J M, Woods R D. A strain of sacbrood virus from Apis cerana. J Invertebr Pathol. 1982;39:264–265. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey L, Gibbs A J, Woods R D. Sacbrood virus of the larval honey bee (Apis mellifera Linnaeus) Virology. 1964;23:425–429. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(64)90266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brčák J, Kralik O. On the structure of the virus causing sacbrood of the honey bee. J Invertebr Pathol. 1965;7:110–111. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(65)90166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh R C, Ball B V, Willcocks M M, Carter M J. The nucleotide sequence of sacbrood virus of the honey bee: an insect picorna-like virus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1514–1549. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee P E, Furgala B. Sacbrood virus: some morphological features and nucleic acid type. J Invertebr Pathol. 1965;7:502–505. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore N F, Reavy B, King L A. General characteristics, gene organisation and expression of small RNA viruses of insects. J Gen Virol. 1985;66:647–659. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman JFE, Brown F, Bailey L, Gibbs A J. Some physico-chemical properties of two honey-bee picornaviruses. J Gen Virol. 1973;19:405–409. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D-I, Moller F E. The division of labor and queen attendance behaviour of nosema-infected worker honey bees. J Econ Entomol. 1970;63:1539–1541. [Google Scholar]

- 16.White G F. Sacbrood. U S Dep Agric Bull. 1917;431:1–55. [Google Scholar]