Abstract

Using the stress process model, the authors investigate whether individuals in interracial relationships experience greater risk for past-year mood and anxiety disorder compared with their same-race relationship counterparts. The authors also assess interracial relationship status differences in external stressors (i.e., discrimination and negative interactions with family) and whether stress exposure explains mental disorder differences between individuals in interracial versus same-race romantic partnerships. Data are from the National Survey of American Life (2001–2003). Results show that individuals in interracial relationships are at greater risk for anxiety disorder (but not mood disorder) relative to those in same-race relationships. Interracially partnered individuals also report more discrimination from the public and greater negative interactions with family. External stressors partially explain the higher risk for anxiety disorder among individuals in interracial partnerships. This study addresses a void in the literature on discrimination, family relationships, and health for the growing population of individuals in interracial unions.

Keywords: interracial relationships, mental health, anxiety, discrimination

Research documents that exposure to stress is unequally distributed in the population and promotes inequalities in health for families (Carr and Springer 2010). For instance, adults in interracial relationships have poorer mental health than those in same-race unions. Specifically, adults in interracial relationships have higher psychological distress (Barr and Simons 2014; Bratter and Eschbach 2006; Miller, Catalina et al. 2022; Miller and Kail 2016), more depressive symptoms (Kroeger and Williams 2011; Wong and Penner 2018), and poorer self-rated health (Barr and Simons 2014; Miller and Kail 2016) compared with those in same-race relationships, though these patterns differ by the racial combination of the pair (Bratter and Eschbach 2006; Kroeger and Williams 2011; Miller, James, and Roy 2022). In some instances, depending on racial combination, interracial coupling can have positive impacts on self-rated health (specifically for non-Black men partnered with Black women) (Miller, Catalina et al. 2022). Nevertheless, several questions remain with regard to our understanding of interracial relationships and mental health. First, although previous research has assessed psychological symptoms, it has not examined the association between interracial relationship status and mental disorder. Second, though several explanations have been offered, empirical examination of reasons for this group’s poorer mental health is limited. Two prominent explanations include experiences with discrimination from the public and disapproval of the relationship by family members. Prior research assessing discrimination experienced by interracial couples is usually qualitative (Childs 2005; Dainton 1999; Killian 2002; Luke and Carrington 2000; McNamara, Tempenis, and Walton 1999; O’Brien 2008; Rosenblatt, Karis, and Powell 1995; Steinbugler 2012), and research on family dynamics usually focus on levels of social support (Bratter and Whitehead 2018; Hohmann-Marriott and Amato 2008), rather than negative interactions. For example, recent quantitative research regarding social support shows that mothers of biracial infants perceive less support from family members (Bratter and Whitehead 2018). Related, Hohmann-Marriott and Amato (2008) found that couples in racially-mixed relationships have less access to instrumental support (provision for a place to stay, emergency babysitting, and money from family) than those in same-race relationships. As such, receiving less social support (though not empirically examined in our study) from family members could precede or be the by-product of negative familial interactions (which we examine).

To fill gaps in the literature on interracial relationship status and health, three questions guide this research: (1) Is being in an interracial relationship (dating, cohabiting, or married) associated with mental disorder? (2) Do individuals in interracial relationships experience more discrimination from the public and negative interactions with family members than their same-race counterparts in intraracial relationships? and (3) If being in an interracial relationship is associated with mental disorder, will stressors (discrimination and negative network dynamics with family members) explain this association? Black and White people in interracial relationships are the focus of this study because these two racialized groups are positioned at opposite ends of the racial hierarchy (Bonilla-Silva 2003). When a Black or White individual forms a romantic relationship with someone of another racial group, the negative responses of others are in part due to differences in the person’s position in the racial hierarchy vis-á-vis their romantic partner’s position.

We make use of the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), a nationally representative psychiatric epidemiology survey developed to assess mental health among U.S. Black adults. Despite its age, NSAL has multiple strengths. First, NSAL allow us to transition from assessing psychological symptoms to assessing mental disorder. Second, determining whether external stressors explain the poorer psychological well-being of individuals in an interracial relationship (found in other studies) necessitate valid and reliable measures. NSAL stress measures explored here (i.e., discrimination and negative interactions with family) meet these criteria (Krieger et al. 2005; Lincoln, Taylor, and Chatters 2012; Taylor, Kamarck, and Shiffman 2004).

Background

Interracial marriages increased exponentially in the United States beginning in the 1960s (Gullickson 2006). In 2000, the year before data collection began for NSAL, approximately 3 percent of White and 7 percent of Black people intermarried (Lee and Edmonston 2005); in addition, 15 percent of cohabitating individuals were in interracial partnerships (Bianchi and Casper 2001). Around that same time, a national survey revealed that 16 percent of White and 2 percent of Black people strongly disapproved of their family members being in interracial relationships, with only 31 percent of White and 48 percent of Black people strongly approving (Bobo 2001).

Interracial Relationship Status as a Devalued Social Position

This study applies major tenets of the stress process model (SPM) to the experience of individuals in interracial relationships. The theoretical underpinning of SPM is that an individual’s location in the social structure (i.e., their social status) differentially exposes him/her to stressors, which can damage mental health (Pearlin 1999; Pearlin et al. 1981). Social status is “connected to virtually every component of the stress process,” influencing exposure to stress, access to resources, as well as mental health (Pearlin 1999:398). Moreover, race, as a social status, represents an important aspect of personal identification and social valorization or devaluation. Race is treated as a social status in SPM. Although we agree, race is also a social structure, rooted in structural racism permeating polices and institutions in America and not simply individualistic in nature or production (Bonilla-Silva 1997). Like Miller (2014) and Tillman and Miller (2017), we posit that being in an interracial relationship is a devalued social position because interracial relationships are marginalized. Being a racial minority or the romantic partner of someone of a devalued racial group exposes one to social stressors. Racial groups are placed on an invisible racial hierarchy that appears relatively fixed for some groups (Whites and Blacks) but may be flexible for other groups (Hispanics and Asians) (Bonilla-Silva 2003; Gans 1999; Lee and Bean 2004). Being in a mixed-race relationship reveals the social construction of racial privilege. Becoming a member of an interracial relationship can lead to diminished or enhanced social status because of the race/ethnicity of one’s partner (Childs 2005; O’Brien 2008).

Research demonstrates that White people prefer that their relatives marry other White people (and oppose interracial relationships) because other groups (especially Black people) are considered inferior to White individuals and less desirable socially, culturally, and economically (Bonilla-Silva and Forman 2000; Feagin, Vera, and Batur 2000; O’Brien 2008; Rosenblatt et al. 1995). White people who prefer marriage to White individuals often do so for racist reasons (Childs 2005; O’Brien 2008; Rosenblatt et al. 1995).

Childs (2005) and Rosenblatt and colleagues (1995) found that in contrast to White persons, Black people prefer romantic in-group relationships as a reaction to racism, because they are aware of racism perpetuated by White people toward them and aware of how other racial groups negatively view them. African-American persons may be regarded as “sellouts” and as having decreased pride in their racial group if they interracially date or marry (Childs 2005; Judice 2008; McNamara et al. 1999). Related, some Black individuals believe that Black persons who interracially date or marry have rejected the Black community (Childs 2005; Killian 2002; McNamara et al. 1999).

Latino persons cite the preservation of cultural aspects of their identity—speaking the ethnic language, observance of cultural holidays, knowledge of preparing cultural foods—as reasons for their preferences for same-ethnic relationships (O’Brien 2008). When Latino individuals’ opposition is specific and not merely a general preference for in-group relationships, they usually reject a romantic relationship with a Black person. The rejection is usually for racist reasons centered on the belief that Black people are culturally inferior (e.g., they live in poverty and have a poor work ethic). O’Brien (2008) also found that Latinos fear that dating or marriage to a Black person might jeopardize their potential to become “honorary Whites.” In essence, although race affects how one experiences marriage and health in same-race relationships (Goodwin 2003; Harris, Lee, and DeLeone 2010; Mouzon 2014; Roxburgh 2014), it is also the case in interracial relationships.

Individuals occupying devalued social statuses experience heightened risk for mental health problems (Turner and Avison 2003). In accordance with our argument that individuals in interracial relationships occupy a devalued social status, interracial relationship status is also associated with poor mental health. However, previous research has only examined unspecified and/or global measures of health among adults (Barr and Simons 2014; Bratter and Eschbach 2006; Kroeger and Williams 2011; Miller and Kail 2016) and adolescents (Miller 2014; Tillman and Miller 2017) in interracial relationships. In this study we assess whether interracial relationship status is associated with mental disorder among Black and White adults. In alignment with past research as well as theoretical expectations set forth by SPM, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 1a: Compared with individuals in same-race relationships, being in an interracial relationship will be associated with higher risk for mood disorder.

Hypothesis 1b: Compared with individuals in same-race relationships, being in an interracial relationship will be associated with higher risk for anxiety disorder.

Interracial Relationship Status and Stress Exposure

Consistent with the SPM tenet that lower social status will be associated with greater stress exposure (Pearlin 1999; Pearlin et al. 1981), individuals in interracial relationships may experience greater exposure to stress (i.e., discrimination and negative interactions with family) compared with people in same-race relationships. Major discrimination involves a past event that interferes with upward mobility (Kessler et al. 1994). Incidents of major discrimination toward individuals in interracial relationships are voiced by participants in qualitative research (Childs 2005; Judice 2008; McNamara et al. 1999; Nemoto 2009; Root 2001; Rosenblatt et al. 1995; Steinbugler 2012) and official criminal reports (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs 2011, 2012). Examples of major discrimination experienced by this group include unfair treatment by the police, steering by real estate agents into segregated or undesirable neighborhoods, as well as physical threats and attacks (Childs 2005; Judice 2008; McNamara et al. 1999; Root 2001; Rosenblatt et al. 1995; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs 2004, 2011, 2012).

Everyday discrimination is a recent occurrence of unfair treatment involving assaults on one’s character (e.g., being treated with less courtesy and respect) (Kessler et al. 1994). Nearly two thirds (64 percent) of Black-White couples are subjected to negative social bias from the public (Dainton 1999) and qualitative research points out the everyday discrimination this group encounters (Childs 2005; Judice 2008; McNamara et al. 1999; Nemoto 2009; Root 2001; Rosenblatt et al. 1995; Steinbugler 2012). Interracial couples are likely to experience everyday discrimination, such as inferior treatment in restaurants or while shopping, racist obscenities yelled by strangers, and difficulties with neighbors (Childs 2005; Judice 2008; McNamara et al. 1999; Nemoto 2009; Root 2001; Rosenblatt et al. 1995; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs 2004, 2011, 2012).

Both major and everyday discrimination occur and have been experienced by interracial couples as shown in qualitative research and criminal justice reports (Childs 2005; Judice 2008; McNamara et al. 1999; Nemoto 2009; Root 2001; Rosenblatt et al. 1995; Steinbugler 2012; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs 2004, 2011, 2012; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs 2012). Although interracial couples share being in a race-discordant relationship, not all social experiences of racial/ethnic groups are the same. For example, previous research shows that Latinos are less likely to report everyday discrimination compared with Black and White persons (Ayalon and Gum 2011). Similarly, Black and White persons in interracial relationships might experience different types of discrimination. Accordingly, we consider both major and everyday discrimination as stressors in this study.

To understand the experiences of people in interracial relationships, we must not only examine unfair treatment from the public (i.e., discrimination) but also negative interactions with relatives. Romanic relationships do not exist in solitude but are socially embedded in social contexts. This social context includes interactions with family members, which can influence how a relationship is experienced (Bryant and Conger 1999; Bell and Hastings 2015; Greif and Saviet 2020; Huston 2000). The level by which family members approve, accept, and tolerate the relationship is likely a valid and particular concern for those in mixed-race relationships.1 Negative interactions with family can be particularly upsetting because this stressor comes from those with whom a person likely loves and has a long and permanent history (Bolger et al. 1989; Neighbors 1997). Examples of negative interactions reported in qualitative studies with relatives include verbal criticism of one’s partner, refusal to acknowledge the partner, negative comments about biracial children, and racist jokes (Childs 2005; Dainton 1999; Killian 2002; Luke and Carrington 2000; McNamara et al. 1999; O’Brien 2008; Osuji 2014; Rosenblatt et al. 1995; Steinbugler 2012). However, Yahirun (2020) found little difference between the emotional closeness individuals in interracial/ethnic marriage feel toward their mothers compared with those in same-race/ethnicity unions. Nevertheless, family networks more broadly may prove problematic and disruptive for individuals in interracial partnerships.

Given the preponderance of evidence from past research, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2a: Individuals in interracial relationships will experience greater exposure to major discrimination compared with their same-race relationship counterparts.

Hypothesis 2b: Individuals in interracial relationships will experience greater exposure to everyday discrimination compared with their same-race relationship counterparts.

Hypothesis 2c: Individuals in interracial relationships will experience greater negative interactions with family compared with their same-race relationship counterparts.

Stress Exposure, Mental Health, and Interracial Relationship Status

SPM proposes that differential exposure to stress can explain status differences in mental health (Pearlin 1999; Turner 2013; Turner and Avison 2003). Accordingly, we propose that stress exposure may explain any observed mental disorder differences between individuals in interracial and same-race relationships. Given the prevalence, gravity, and enduring bias interracial couples encounter, discrimination may be a primary stressor underlying poorer psychological health for those in interracial pairings compared with those in monoracial pairings. Discrimination functions to reinforce symbolic boundaries between advantaged and disadvantaged relationships. Previous research demonstrates a positive link between perceived discrimination and mood disorder (Gibbons et al. 2004; Seaton et al. 2008) as well as anxiety disorder (Alang, McAlpine, and McClain 2021; Gaylord-Harden and Cunningham 2009). Because of the potential for disproportionately higher exposure to discrimination among individuals in interracial relationships, we offer the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Major discrimination will partially explain the association between interracial status and the presence of mood disorder.

Hypothesis 3b: Everyday discrimination will partially explain the association between interracial status and the presence of mood disorder.

Hypothesis 3c: Major discrimination will partially explain the association between interracial status and the presence of anxiety disorder.

Hypothesis 3d: Everyday discrimination will partially explain the association between interracial status and the presence of anxiety disorder.

Despite being on the receiving end of unfair treatment from the public, negative family interactions may be even more problematic for the mental health of individuals in interracial relationships. Awareness that relatives devalue one’s relationship can be deleterious to health because one must always be on guard about others’ reactions to the relationship. Regardless of interracial status, negative relationships with family members exert negative effects on health (Bryant, Conger, and Meehan 2001; Goodwin 2003; Timmer and Veroff 2000) and are linked to poorer psychological functioning (Krause 2005; Rook 1992) and negative affect (Newsom et al. 2003). Even infrequent negative interactions undermine mental and physical health (Krause 2005; Rook 1992). Regarding individuals in interracial relationships, weak parental support is associated with depressive symptoms (Henderson and Brantley 2019; Rosenthal et al. 2019) and stigma from family is associated with anxiety symptoms (Rosenthal et al. 2019). None of these studies, however, assess mental health using psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Our final hypotheses are related to the role of negative interactions with family:

Hypothesis 3e: Negative interactions with family will partially explain the association between interracial status and the presence of mood disorder.

Hypothesis 3f: Negative interactions with family will partially explain the association between interracial status and the presence of anxiety disorder.

The Present Study

This study of how stress exposure influences mental health among interracial relationships (compared with monoracial relationships) contributes to several bodies of research: the sociology of the family, sociology of health and illness, and the study of race and racism. This study speaks to the sociology of the family by showing how an alternative family formation (other than a same-race formation) has implications for family dynamics and health outcomes. Previous research has demonstrated a health advantage for married persons (Goldman, Korenman, and Weinstein 1995; Lillard, Brien, and Waite 1995). However, not all marriages are equal. Studying interracial relationships also raises questions about whether and how the effects of discrimination experienced by the couple may filter to the children from such relationships.

Regarding the study of health and illness, one’s health status does not simply reflect biological exposure to pathogens. In the case of interracial couples, the presence of mental disorder can speak to the impact of stressful racialized experiences because of intimate social interaction with someone of a racial group different than one’s own. Thus, it is not simply how one’s race affects exposure to racism and its subsequent impact on health but how crossing racial boundaries affects something seemingly quite personal as health.

As it relates to the sociology of race and racism, the experiences of interracial couples are important to study because it is an exemplar of the complex nature of racism’s operation in society. Discrimination is often regarded as a “Black” or minority issue. However, studying the racialized experiences of interracial couples show how racism is a societal issue. Entering an interracial relationship is a means through which White persons can personally feel the racial hierarchy that positions White persons at the top and Black persons at the bottom. Studying interracial couples’ experiences reveal racism’s consequences (e.g., health), often exposing covert sentiments regarding racial groups different than one’s own. This occurs either because people challenge the established racial hierarchy by seeing others as racial equals (by desiring and accepting a race-discordant spouse) or by establishing an intimate association with someone of a racial group different than their own.

Data and Method

Data are from NSAL, a premier psychiatric epidemiological survey providing a nationally representative sample and national estimates of psychiatric disorders among Black Americans (Heeringa et al. 2004; Jackson et al. 2004). Despite being collected in the early 2000s (2001–2003), NSAL is well suited for this analysis for several reasons. NSAL is the only large-scale dataset that enables an assessment of both interracial relationship status and discrimination; this is a critical strength, as other data sources do not allow an examination of explanatory mechanisms underlying the relatively worse mental health of individuals in interracial relationships compared with their same-race relationship counterparts. Generally, prior quantitative research pertaining to interracial couples uses the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) (Kroeger and Williams 2011; Vaquera and Kao 2005; Wang, Kao, and Joyner 2006; Wong and Penner 2018). Although Add Health includes depression and anxiety symptom measures, mental disorder is not assessed. The Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study, a more recent survey that asks about interracial relationship status, does not include measures assessing unfair treatment (Bratter and Whitehead 2018).

The NSAL includes 5,191 non-Hispanic Black (hereafter Black) (3,570 African Americans, 1,621 Afro-Caribbeans) and 891 non-Hispanic White (hereafter White) respondents. The overall NSAL response rate was 71.3 percent. Surveys were conducted in English, and the majority were in person (86 percent) (Heeringa et al. 2004; Jackson et al. 2004). On the basis of 1990 U.S. census estimates, respondents were drawn from census blocks where at least 10 percent of residents were Black. White NSAL respondents also resided in the same census tracts from which the Black sample was drawn.

Given that the sample was composed of Black and White respondents, we are unable to assess the psychological impact of interracial romantic partnerships for non-Black ethnic minorities. In addition, respondents’ reporting on their partner’s race or ethnicity is not sufficiently detailed to make meaningful comparisons between different racial combinations (e.g., Black-White, Black-Asian) among interracial couples.

In our analytic sample, 2,297 respondents were not married, cohabiting, or dating at the time of interview and were removed. In the data, 466 respondents had missing data on key study measures. For example, 310 respondents did not report the racial background of their romantic partners, and 86 respondents did not have data on mental health. To provide context for the high number of missing responses on race of the romantic partner, only respondents who reported being in relationships for at least one year were queried about the racial background of their partners. We consider this a strength, as a longer length of time in a relationship may reflect greater commitment, as opposed to a casual or less serious relationship. Only respondents with complete data were retained. Thus, the restricted sample for the analysis includes 3,136 respondents (n = 322 in interracial relationships, n = 2,814 in same-race relationships). Of respondents in interracial romantic partnerships, 262 were Black and 60 were White.

Dependent Measures

Mental health was captured by any 12-month mood disorder and any 12-month anxiety disorder. To make determinations about the presence of a psychiatric disorder in the past year, the World Mental Health Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used. This instrument assesses the most common and severe mental disorders using diagnostic criteria established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Any 12-month mood disorder was coded 1 if respondents met criteria for a mood disorder (e.g., major depressive episode, bipolar I and II). Any 12-month anxiety disorder was coded 1 if respondents met criteria for an anxiety disorder (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, panic attack).

Independent Measures

Interracial relationship status was assessed using the question “Please tell me which group best describes your (spouse’s/partner’s) race: Black or African American, White, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, or Pacific Islander?” In the public use data, however, racial categories included Black, White, and other. Using this item as well as the respondent’s self-identified race (i.e., Black or White), we constructed a binary measure of interracial status that distinguished between those in interracial (1) versus same-race (0) relationships. As noted earlier, 322 respondents were in interracial relationships. Of those 322 respondents in interracial relationships, the racial combinations included a Black respondent with a White partner (n = 78), a White respondent with a Black partner (n = 23), a Black respondent with an “other race” partner (n = 184), and a White respondent with an “other race” partner (n = 37).

We assess five measures of stress exposure: major discrimination, everyday discrimination, race-related major discrimination, race-related everyday discrimination, and negative interactions with relatives. In the context of interracial relationships, it is important to assess perceived discrimination, irrespective of the reason, as well as whether discrimination was attributed to race. This distinction is critical because individuals in interracial romantic partnerships may not recognize discrimination when it occurs or may attribute the discrimination to other characteristics because of a denial of racism or because of an endorsement of color-blind logics of race (Childs 2005). Moreover, past research confirms that the health effects of racial versus nonattributional reasons for discrimination are distinct (Brown 2001). Major discrimination and everyday discrimination (Essed 1991; Williams et al. 1997) were used to assess unfair treatment regardless of attribution. Major discrimination is an index of the number of respondent-reported experiences of nine major events: (1) unfairly fired, (2) unfairly denied a promotion, (3) unfairly not hired, (4) stopped, searched, questioned, physically threatened or abused by the police, (5) prevented from moving into a neighborhood, (6) denied a bank loan, (7) lived in a neighborhood where neighbors made life difficult, (8) unfairly discouraged by a teacher or an adviser from continuing education, or (9) received service that was worse than what other people received. Respondents answered yes (1) or no (0) to each experience, and a summed index was created with a possible range of 0 to 9. Because less than 6 percent of respondents reported more than three events, responses were truncated so that the measure ranges from 0 to 3 or more.

For everyday discrimination, respondents were queried regarding the frequency with which they experienced 10 occurrences of unfair treatment: (1) being treated with less courtesy than others, (2) being treated with less respect than others, (3) receiving poorer service than others at restaurants or stores, (4) being treated as if you are not smart by others, (5) others being afraid of you, (6) being perceived as dishonest by others, (7) people acting like they are better than you, (8) being called names and insulted by others, (9) being threatened or harassed, and (10) being followed around in stores (Essed 1991; Williams et al. 1997). Response options included: “never” (0), “less than once a year” (1), “a few times a year” (2), “a few times a month” (3), “at least once a week” (4), and “almost everyday” (5). A mean standardized scale was created (α = .89). Standardized scores range from −0.92 to 3.26, with higher scores reflecting more frequent discrimination.

Two measures capture discrimination attributed to race. For race-related major discrimination, respondents who answered the major discrimination items were asked to select a primary reason for each event, with options including ancestry or national origin, gender, race, age, height or weight, shade of skin color, or other. Consistent with prior research (Mouzon et al. 2017), a selection of ancestry, national origin, ethnicity, race, or skin color as the reason for one or more of the unequal experiences denotes race-related major discrimination (1). Race-related everyday discrimination was assessed using a single question posed to respondents after reporting their responses to the everyday discrimination scale items: “What do you think was the main reason for these experiences?” Response options included ancestry or national origin or ethnicity, gender or sex, race, age, height, skin color, sexual orientation, weight, income or educational level, or other. A selection of ancestry or national origin or ethnicity, race, or skin color as a reason for the unequal experience denotes race-related everyday discrimination (1). The race-related everyday discrimination question was asked once (after the battery of everyday discrimination questions); thus, this is an overall measure of why the respondent perceived unfair daily treatment across several situational contexts.

Last, negative interactions with family members was assessed using three items that queried the extent to which family members (other than spouse or partner): “criticize you and the things you do,” “make too many demands on you,” and “try to take advantage of you.” Response options included “never” (0), “not too often” (1), “fairly often” (2), and “very often” (3). A summed index was created with a possible range of 0 to 9 (Lincoln et al. 2012). Higher scores indicate a greater frequency of negative encounters with family.

Control Measures

We control for two aspects of relationships that may also be relevant for mental health. First, we adjust for relationship status, distinguishing among respondents who are married (reference), cohabiting (but unmarried), and dating but not cohabiting. Second, relationship satisfaction, a measure of relationship quality, assesses the level of satisfaction with one’s current relationship (Bryant et al. 2008; Lincoln, Taylor, and Jackson 2008). Response options include: “very dissatisfied” (1), “somewhat dissatisfied” (2), “somewhat satisfied” (3), and “very satisfied” (4). Higher values reflect better relationship quality.

We adjust for several sociodemographic correlates of mental health. Ethnicity distinguishes among African American (reference), Afro-Caribbean, and White respondents. Sex distinguishes between women (1) and men (0). Age is measured in years (range = 18–90 years). Nativity distinguishes between U.S. born (1) and foreign born (0). Number of children in the household ranges from zero to four or more. Annual household income is a continuous measure, measured in $10,000s, and top-coded at $200,000 (Erving 2021). Values range from 0 to 20. Educational attainment distinguishes among less than high school (reference), high school, some college, and college graduate. Region of residence include South (reference), Northeast, Midwest, and West.

Analytic Strategy

The analysis proceeds in the following steps. First, descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1 to identify differences in mood disorder, anxiety disorder, stress exposure, and controls by interracial relationship status. Second, binary logistic regression models are used to identify the association between interracial relationship status and mental health in Table 2 (12-month mood disorder) and Table 3 (12-month anxiety disorder). The first model adjusts for relationship-related and sociodemographic controls. Models 2, 3, and 4 introduce three sets of stressors (i.e., major and everyday discrimination, race-related discrimination, and negative interactions with family) one at a time. Then, model 5 adjusts for all stressors. Third, we assessed whether stress exposure mediated the relationship between interracial relationship status and mental disorder. Reductions in the magnitude and significance of the odds ratios (ORs) across models that adjust for stressors provide only suggestive evidence of mediation. Therefore, we conducted formal mediation analyses using the medeff command (Hicks and Tingley 2011) in Stata (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Mediation results are reported in Table 4. We present unweighted analyses, which were conducted using Stata 16.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Measures (n = 3,136).

| Same Race (n = 2814) |

Interracial (n = 322) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Proportion | SD | Mean/Proportion | SD | Significance | |

| Dependent measures | |||||

| Any 12-month mood disorder | .06 | .08 | |||

| Any 12-month anxiety disorder | .l4 | .20 | * | ||

| Stressors (range) | |||||

| Major discrimination (0 to 3) | 1.08 | l.l2 | 1.37 | l.l8 | * |

| Everyday discrimination (−.92 to 3.26) | −.02 | .68 | .l5 | .75 | * |

| Race-related major discrimination (0 or 1) | .20 | .23 | |||

| Race-related everyday discrimination (0 or 1) | .50 | .50 | |||

| Negative interactions with family (0 to 9) | 2.45 | 2.23 | 2.83 | 2.41 | * |

| Controls (range) | |||||

| Relationship status | |||||

| Married (reference) | .57 | .45 | * | ||

| Cohabiting | .l2 | .l7 | * | ||

| Dating, but not cohabiting | .31 | .38 | * | ||

| Relationship satisfaction (1 to 4) | 3.48 | .70 | 3.43 | .75 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| African American (reference) | .59 | .49 | * | ||

| Afro-Caribbean | .25 | .32 | * | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | .l6 | .l9 | |||

| Female | .59 | .49 | * | ||

| Age (years) (18 to 90) | 41.71 | 14.30 | 38.75 | 13.78 | * |

| U.S. born | .79 | .75 | |||

| Number of children in household (0 to ≥4) | .65 | 1.00 | .60 | .93 | |

| Household income (in $l0,000s) (0 to ≥20) | 4.32 | 3.35 | 4.29 | 3.45 | |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| less than high school (reference) | .21 | .l7 | * | ||

| High school | .35 | .35 | |||

| Some college | .24 | .28 | |||

| College graduate | .20 | .20 | |||

| Region | |||||

| South (reference) | .59 | .43 | * | ||

| Northeast | .26 | .36 | * | ||

| Midwest | .l0 | .l0 | |||

| West | .05 | .11 | * | ||

Source: National Survey of American Life (2001–2003).

Significantly different at p < .05 by t test.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios of Binary Logistic Regressions Predicting 12-Month Mood Disorder (n = 3,136).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interracial relationship | 1.217 (.286) | 1.060 (.255) | 1.208 (.285) | 1.107 (.266) | .992 (.243) |

| Stressors | |||||

| Major discrimination | 1.223** (.091) | 1.179* (.0897) | |||

| Everyday discrimination | 1.869*** (.208) | 1.654*** (.198) | |||

| Race-related major discrimination | 1.173 (.222) | 1.119 (.218) | |||

| Race-related everyday discrimination | 1.411 (.25l) | .962 (.184) | |||

| Negative interactions with family | 1.268*** (.039) | 1.214*** (.039) | |||

| Controls | |||||

| Cohabitinga | 1.022 (.243) | .951 (.229) | 1.016 (.242) | .931 (.226) | .900 (.220) |

| Dating, but not cohabiting | .816 (.161) | .847 (.168) | .824 (.162) | .793 (.159) | .825 (.166) |

| Relationship satisfaction | .557*** (.051) | .612*** (.057) | .562*** (.051) | .603*** (.057) | .640*** (.061) |

| Afro-Caribbeana | 1.160 (.347) | 1.220 (.369) | 1.167 (.349) | 1.194 (.363) | 1.261 (.385) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.895** (.407) | 2.354*** (.522) | 2.352*** (.562) | 2.177*** (.480) | 2.487*** (.622) |

| Female | 1.349 (.237) | 1.725** (.316) | 1.392 (.245) | 1.286 (.228) | 1.596* (.296) |

| Age | .983* (.007) | .989 (.007) | .984* (.007) | .988 (.007) | .991 (.007) |

| U.S. born | 1.448 (.435) | 1.248 (.374) | 1.435 (.430) | 1.311 (.396) | 1.216 (.367) |

| Number of children in household | 1.100 (.082) | 1.114 (.084) | l.l0l (.083) | 1.080 (.082) | 1.095 (.084) |

| Household income | .893** (.032) | .895** (.032) | .890** (.032) | .901** (.032) | .900** (.032) |

| High schoola | .868 (.179) | .899 (.189) | .859 (.177) | .923 (.194) | .943 (.201) |

| Some college | .804 (.190) | .778 (.187) | .782 (.185) | .825 (.198) | .817 (.199) |

| College graduate | .968 (.267) | .950 (.268) | .940 (.259) | 1.039 (.291) | 1.025 (.292) |

| Northeasta | 1.437 (.326) | 1.259 (.294) | 1.410 (.321) | 1.306 (.303) | 1.187 (.281) |

| Midwest | 2.317*** (.500) | 2.140*** (.471) | 2.326*** (.503) | 2.199*** (.485) | 2.074** (.463) |

| West | 1.305 (.446) | 1.121 (.391) | 1.290 (.442) | 1.354 (.469) | 1.209 (.426) |

Source: National Survey of American Life (2001–2003).

Note: Values in parentheses are standard errors.

The reference categories for relationship status, ethnicity, education, and region are married, African American, less than high school, and South, respectively.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios of Binary Logistic Regressions Predicting 12-Month Anxiety Disorder (n = 3,136).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interracial relationship | 1.426* (.227) | 1.289 (.210) | 1.418* (.226) | 1.349 (.219) | 1.238 (.204) |

| Stressors | |||||

| Major discrimination | 1.292*** (.065) | 1.262*** (.066) | |||

| Everyday discrimination | 1.576*** (.125) | 1.473*** (.126) | |||

| race-related major discrimination | 1.307* (.165) | 1.209 (.156) | |||

| Race-related everyday discrimination | 1.226 (.141) | .861 (.108) | |||

| Negative interactions with family | 1.196*** (.026) | 1.149*** (.026) | |||

| Controls | |||||

| Cohabitinga | 1.538** (.240) | 1.454* (.231) | 1.535** (.240) | 1.456* (.231) | 1.417* (.227) |

| Dating, but not cohabiting | 1.067 (.140) | 1.092 (.145) | 1.077 (.142) | 1.047 (.140) | 1.072 (.144) |

| Relationship satisfaction | .646*** (.043) | .705*** (.048) | .653*** (.044) | .689*** (.047) | .732*** (.051) |

| Afro-Caribbeana | .963 (.194) | .992 (.202) | .971 (.196) | .985 (.200) | 1.013 (.207) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.189 (.182) | 1.390* (.219) | 1.381 (.230) | 1.276 (.199) | 1.356 (.233) |

| Female | 1.694*** (.197) | 2.135*** (.261) | 1.748*** (.205) | 1.653*** (.194) | 2.048*** (.252) |

| Age | .989** (.004) | .992 (.005) | .989* (.004) | .992 (.004) | .994 (.005) |

| U.S. born | 1.402 (.283) | 1.218 (.247) | 1.391 (.280) | 1.334 (.271) | 1.208 (.246) |

| Number of children in household | 1.023 (.054) | 1.025 (.055) | 1.025 (.054) | 1.004 (.054) | 1.012 (.055) |

| Household income | .947* (.021) | .943** (.020) | .945** (.020) | .950* (.020) | .946* (.020) |

| High schoola | .798 (.111) | .811 (.115) | .787 (.110) | .830 (.118) | .834 (.120) |

| Some college | .701* (.112) | .664* (.108) | .686* (.110) | .707* (.114) | .680* (.112) |

| College graduate | .826 (.152) | .777 (.146) | .807 (.149) | .861 (.160) | .817 (.155) |

| Northeasta | 1.259 (.187) | 1.107 (.170) | 1.239 (.185) | 1.172 (.177) | 1.063 (.164) |

| Midwest | 1.536** (.243) | 1.376* (.222) | 1.524** (.241) | 1.459* (.235) | 1.320 (.216) |

| West | .989 (.234) | .856 (.208) | .985 (.234) | 1.011 (.241) | .899 (.219) |

Source: National Survey of American Life (2001–2003).

Note: Values in parentheses are standard errors.

The reference categories for relationship status, ethnicity, education, and region are married, African American, less than high school, and South, respectively.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 4.

Mediation Analysis for 12-Month Anxiety Disorder.

| Average Mediation | Average Direct Effect | % of Total Effect Mediated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stressor | |||

| Major discrimination | .010 | .035 | 21.80 |

| Everyday discrimination | .009 | .038 | 18.43 |

| Race-related major discrimination | .001 | .044 | 2.94 |

| Race-related everyday discrimination | <.001 | .046 | <.01 |

| Negative interactions with family | .007 | .038 | 15.49 |

Source: National Survey of American Life (2001–2003).

Note: Mediation analysis is based on use of the medeff command in Stata. Mediation analysis is based on a model that adjusts for all study controls.

Results

Descriptive statistics, by same-race versus interracial relationship status, are reported in Table 1. In terms of mental health, 6 percent of individuals in same-race relationships and 8 percent of individuals in interracial relationships experienced a mood disorder in the past year. Those in interracial relationships (20 percent) have significantly higher rates of 12-month anxiety disorder relative to those in same-race relationships (14 percent). With regard to stress exposure, three significant differences emerge: major discrimination, everyday discrimination, and negative interactions with family members are relatively higher among individuals in interracial relationships compared with their same-race relationship counterparts. Thus, hypothesis 2a, 2b, and 2c are supported. Interestingly, no differences in race-related (major and everyday) discrimination were present.

With regard to the study controls, same-race relationship status is associated with higher rates of marriage (57 percent vs. 45 percent among interracial relationships) but lower rates of cohabiting (12 percent vs. 17 percent) and dating (31 percent vs. 38 percent). Individuals in racially homogenous relationships were more likely to be African American yet less likely to be Afro-Caribbean than those in interracial romantic partnerships. Individuals in interracial romantic partnerships were more likely to be male (51 percent) and younger (38.75 years) compared with those in same-race relationships (41 percent male, 41.71 years of age). With regard to education, individuals in same-race unions were more likely to have less than a high school diploma (21 percent) compared with those in interracial unions (17 percent). The regional distribution of same-race and interracial couples also differs in that same-race couples are more likely to reside in the South (59 percent) than interracial couples (43 percent). However, respondents in interracial partnerships have greater representation in the Northeast (36 percent) and West (11 percent) than their same-race relationship counterparts (26 percent in Northeast, 5 percent in the West).

Table 2 presents ORs from binary logistic regression models assessing the association between interracial relationship status and any 12-month mood disorder. In model 1, which adjusts for controls, those in cross-racial romantic partnerships do not significantly differ from those in same-race relationships. Thus, hypothesis 1a is unsupported. After adjusting for major and everyday discrimination in model 2, race-related discrimination in model 3, and negative interactions with family members in model 4, the OR for interracial relationship status is not altered substantially in terms of magnitude nor statistical significance. In model 5, the full model, which adjusts for all three sets of stressors, the interracial relationship OR is not significant. In other words, there appear to be no discernable differences in 12-month mood disorder for individuals in same-race versus cross-racial relationships. However, consistent with stress theory, in the full model, major discrimination (OR = 1.179, p < .05), everyday discrimination (OR = 1.654, p < .001), and negative interactions with family (OR = 1.214, p < .001) are associated with greater odds of 12-month mood disorder. With respect to study control measures, relationship satisfaction is associated with lower risk for 12-month mood disorder. Compared with African Americans, White respondents have higher risk for 12-month mood disorder. Women have greater risk for 12-month mood disorder. Higher household income is associated with lower risk, while residing in the Midwest (compared with the South) is associated with greater risk for 12-month mood disorder. Because no differences in 12-month mood disorder by interracial relationship status were identified, mediation analyses were not explored. As such, hypotheses related to mood disorder, hypothesis 3a, 3b, and 3e, are unsupported.

In Table 3, the association between interracial relationship status and 12-month anxiety disorder is investigated with binary logistic regression analysis. ORs are reported. In model 1, adjusting for study controls, interracial relationship status is associated with 1.426 (p < .05) greater odds of 12-month anxiety relative to those in same-race partnerships. Thus, hypothesis 1b is supported. In model 2 which includes nonspecific major and everyday discrimination, interracial relationship status is no longer statistically significant, but the OR remains substantial, at 1.289. Major discrimination (OR = 1.292, p < .001) and everyday discrimination (OR = 1.576, p < .001) are associated with greater odds of 12-month anxiety disorder. Model 3 includes race-related discrimination: race-related major discrimination (OR = 1.307, p < .05) is associated with greater odds of 12-month anxiety disorder yet interracial relationship status remains significant (OR = 1.418, p < .05). In model 4, negative interactions with family (OR = 1.196, p < .001) is associated with greater odds of 12-month anxiety disorder. In model 4, the OR for interracial status is no longer significant, but the OR is 1.349. Last, in the full model (model 5), interracial relationship status is no longer significant (OR = 1.238). In addition, major discrimination (OR = 1.262, p < .001), everyday discrimination (OR = 1.473, p < .001), and negative interactions with family (OR = 1.149, p < .001) are related to greater odds of 12-month anxiety disorder. These results overall suggest that everyday and major discrimination and negative interactions with family members explain the higher risk for past-year anxiety disorder among individuals in interracial relationships compared with their counterparts in same-race partnerships. With regard to study controls, cohabiters have higher odds of past-year anxiety disorder than the married. Higher relationship satisfaction, being male, higher household income, and some college (compared with less than high school) is associated with lower risk for 12-month anxiety disorder.

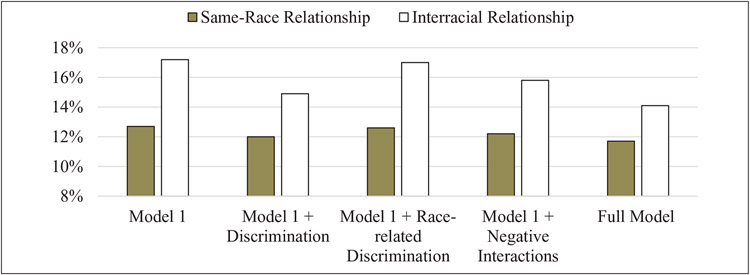

To provide a visual representation of the association between interracial relationship status and past-year anxiety disorder, predicted probabilities on the basis of the models presented in Table 3 are shown in Figure 1. Predicted probabilities were produced setting all other covariates at their means. In model 1, which adjusts for study controls, the predicted probability of past-year anxiety was 12.7 percent for individuals in same-race and 17.2 percent for those in interracial relationships (a difference of 4.5 percent; see bars above “Model 1”). Accounting for major and everyday discrimination reduces the predicted probability to 12.0 percent for same-race relationship and 14.9 percent for individuals in interracial partnerships (see bars above “Model 1 + Discrimination”). Accounting for race-related discrimination does not alter the predicted probability of anxiety disorder for individuals in interracial relationships. Adjusting for negative interactions with family, however, reduces the predicted probability of past-year anxiety disorder to 12.2 percent for same-race relationships and 15.8 percent for individuals in interracial relationships (see bars above “Model 1 + Negative Interactions”). After accounting for all three sets of stressors, the predicted probability of 12-month anxiety is reduced to 11.7 percent for those in same-race relationships and 14.1 percent for those in interracial partnerships (a difference of 2.4 percent). In sum, observed changes in predicted probabilities across models suggests that stress exposure explains some (but not all) of the difference in past-year anxiety disorder between individuals in same-race and interracial relationships. A formal mediation analysis, however, is necessary to confirm this conjecture.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of 12-month anxiety disorder by interracial relationship status.

Note: Predicted probabilities are based on models 1 to 5 in Table 3. All covariates were set at their means.

In Table 4, results from mediation analyses for 12-month anxiety disorder are reported. Each stressor had to be tested for mediation one at a time. The column reporting the percentage of total effect mediated is of particular interest for our purposes. The mediation analysis reveals that 21.80 percent of the association between interracial relationship status and 12-month anxiety disorder is explained by major discrimination. Hypothesis 3c is supported. Approximately 18.43 percent of the interracial relationship-anxiety disorder association is explained by everyday discrimination; thus, hypothesis 3d is supported. As anticipated (on the basis of results presented in Table 3), race-related (major or everyday) discrimination does not mediate a substantial portion of the association between interracial relationship status and past-year anxiety disorder. However, negative interactions with family members mediated 15.49 percent of the association between interracial relationship status and 12-month anxiety disorder. As such, hypothesis 3f is supported. Collectively, the stressors explored here explain 58.66 percent of the heightened risk for 12-month anxiety disorder for individuals in interracial relationships compared with those in same-race partnerships.

Discussion

Using the SPM as a framework, this study explored whether external stressors, specifically major and everyday discrimination and negative family interactions, would explain differences in mental disorder for those in racially mixed relationships compared with those in same-race relationships. This study systematically examined the effect of discrimination and negative interactions on the mental health of those in interracial relationships using NSAL. The inclusion of stress measures is paramount because scholars have speculated that these factors might explain poorer outcomes for those in interracial unions but have not generally empirically investigated the relationship. Our findings show that external factors play a role in the negative penalties on health that affect Black and White persons in interracial relationships. These effects are rather large in that symptoms of poor mental health were not examined, but instead the presence of mental disorder.

Our first research question asked whether being in an interracial relationship (dating, cohabiting, or married) was associated with mental disorder. After adjusting for sociodemographic factors, those in interracial relationships had higher odds of anxiety disorder compared with those in mixed-race partnerships, but not mood disorder. This result indicates that the stress of being in an interracial relationship might be more detrimental to health than previously thought. Being in an interracial relationship is associated with psychological symptoms (Barr and Simons 2014; Bratter and Eschbach 2006; Kroeger and Williams 2011; Miller and Kail 2016; Rosenthal et al. 2019; Wong and Penner 2018), but also psychological disorder, namely anxiety disorder. Taken together, the findings suggest that individuals in interracial relationships may not be sad (manifested as mood disorder) but instead worried (manifested as anxiety) about anticipated or perceived discrimination because of their devalued relationship.

Next, we asked whether individuals in interracial relationships experience more discrimination from the public and negative interactions with family members than their same-race counterparts in intraracial relationships. Consistent with our theoretical expectations, individuals in interracial relationships reported more major and everyday discrimination. We then asked whether discrimination and negative network dynamics with family members would explain the association between interracial status and mental disorder. We found that major and everyday discrimination partially mediated the relationship between being in an interracial relationship and anxiety disorder. Surprisingly race-related major and race-related everyday discrimination did not mediate the linkage between interracial relationship status and mental disorder. Indeed, discrimination from being in an interracial relationship is not simply a result of one’s race but the intersection of one’s race with another person’s race. Regarding family dynamics, results show that those in mixed-race relationships report more negative interactions with family and a greater frequency of negative interactions with family partially mediates the relationship between interracial status and anxiety disorder.

In the 20 years since NSAL was collected, the United States has witnessed family and demographic changes. A reasonable question may be, have things changed for the better or worse for people in interracial relationships? In terms of health, discrimination has and continues to exert a negative influence on health (Clark, Salas-Wright, and Whitfield 2015; Gaylord-Harden and Cunningham 2009; Hunte and Barry 2012; Lewis, Cogburn, and Williams 2015; Nadimpalli et al. 2016; Paradies et al. 2015). As such, our understanding of interracial relationships and its association with mental health likely remains negative. In terms of the experience of being in an interracial relationship, research shows that racial attitudes among young White Americans (those most likely to have more tolerant racial attitudes) have changed more so in form, but not substance; color-blind racism existed 20 years ago (Bonilla-Silva 2003) and persists to the present day (Forman and Lewis 2015). Bonilla-Silva (2003) found that a significant portion of White Americans express doubts and concerns about the viability of interracial romantic partnerships, with some drawing attention to potential racism and other challenges for children of interracial unions. Although a smaller proportion of Black Americans in the same study reported concerns about interracial relationships, they expressed concerns about potential rejection and exclusion from family members of a White romantic partner.

In the contemporary era, there will likely be more social interaction between people of different racial groups on varying levels because of an increase in interracial romantic relationships and the widespread promotion of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” efforts across societal institutions. Findings from this research suggest that the promotion and presence of cross-racial relationships (intimate and platonic), despite their increase, does not equate to greater societal acceptance. As such, in this contemporary era we should be vigilant in interrogating how the consequences of increasingly diverse social interactions differentially affect racial groups (Ince 2022). In sum, we believe our results are germane to present-day dynamics because of the unrelenting pervasiveness of racism in U.S. society.

Every study comes with limitations, and this study is no different. The discrimination questions in NSAL do not ask specifically whether discrimination has occurred because of the interracial nature of one’s relationship. Qualitative research suggests that much of the treatment against interracial couples is subtle in nature, such as receiving stares from others and racist comments voiced by people. Such instances are not directly captured in NSAL measures. Nonetheless, prior research has also used the Everyday Discrimination Scale to assess discriminatory experiences among interracial couples (Rosenthal et al. 2019). Specifying questions to make them reflective of those in interracial relationships would likely lead to a greater endorsement of discrimination and a stronger association between discrimination and psychiatric disorder.

A second limitation is that Black and White persons in interracial relationships are analyzed as one group. This could be problematic because in some studies, Black individuals have better mental health than White individuals, but in other studies, Black persons have a similar mental health profile as White persons (Jackson 1997; Mouzon 2014; Mouzon et al. 2017; Pamplin and Bates 2021). Third, we include dating respondents in the analysis. Dating couples may have somewhat different experiences than married or cohabiting couples (particularly with family members); however, it is reasonable to assume that the public does not differentiate in terms of discrimination between dating versus married or cohabiting partners and relationship status is not always readily apparent.

This research highlights findings from a cross-sectional data source. Future research should examine the mental health of individuals in interracial relationships over time. It is possible that the negative effects of being in an interracial relationship may weaken over time. Qualitative research finds that long-term partnerships generally experience decreased opposition over time from relatives, either because the family comes to see the partner as a racial/ethnic exception, begins to view race/ethnicity in a different way, or unites because of the birth of a child (Childs 2005; Judice 2008; McNamara et al. 1999; Root 2001; Rosenblatt et al. 1995). Additionally, over time, mixed-race couples may develop strategies for dealing with discrimination that protect their well-being.

LeBlanc, Frost, and Wight (2015) called for an integration of the SPM, minority stress theory, and couple-level minority stress theory, for understanding how status (e.g., racial minority) and role-based (e.g., partner or spouse) stress affect mental health through discrimination (minority stressors) and relational stress (conflict between couples). With respect to stress theory, this research suggests that romantic dyadic relationships may influence exposure to stressors and subsequent health through social association for individuals in interracial pairings. Social inequality may exist because of the intersection between one’s own social characteristics (i.e., one’s race) and the social characteristics of those with whom one forms an intimate relationship (i.e., their partner’s race). The social association has a strong impact on health (as does one’s personal social characteristics). As surveys begin to ask about the race and ethnicity of one’s partner, researchers can conduct research to understand how couple-level minority stressors that stem from stigmatized relationships, specifically interracial partnerships, affect these marginalized couples.

Families are increasingly becoming more diverse; yet interracial couples still remain largely invisible in society. Interracial couples do not see themselves widely represented in the media, couples with children are presumed to not be the parents, and children of these unions are not given texts and classes that support their family unit (Onwuachi-Willig and Willig-Onwuachi 2009). Family members and others concerned about people who cross the color line for intimacy should be aware of how they influence the experience of those in interracial relationships. Regarding practice, family therapists, psychologists, family advocates, and practitioners should be trained in understanding the unique experiences of interracial couples. Such training would enable practitioners to effectively support the socioemotional needs and healthy family functioning of interracial families.

Although the rate of intermarriage has increased over time and surveys indicate greater acceptance of these relationships, research documents that people in interracial relationships experience stigma and discrimination (Childs 2005; Dainton 1999; Killian 2002; Luke and Carrington 2000; McNamara et al. 1999; O’Brien 2008; Rosenblatt et al. 1995; Rosenthal et al. 2019; Steinbugler 2012). However, some racial groups are viewed as more acceptable marital partners than other racial groups. In 2009, research using the 2008 American Community Survey showed that 80 percent of respondents were comfortable with intermarriage by a family member, but acceptance differed with specification of the race of the hypothetical partner. Within one’s own family, respondents were more comfortable with intermarriages in which the spouse would be White (81 percent), followed by Asian (75 percent), then Hispanic (73 percent), and last Black (66 percent) (Livingston and Brown 2017). Indeed, in our study, Black-White romantic partnerships were less common than Black-other and White-other romantic partnerships. This confirms, somewhat, the notion that Black-White unions are still the most taboo and less frequent compared with Black and White individuals’ marrying other ethnic minority groups. What do we make of these findings overall? Killian (2013) reminded us that the interpretation of the percentage of people who oppose and accept interracial relationships are dependent on the individual. In one regard, the increasing number of people who approve or support the legalization of intermarriage points to improvement in racial tolerance and social distance; on the other hand, persistence in the number of people who disapprove of such relationships show continued intolerance for interracial relationships. Thus, improvement exists though intolerance persists.

Taken together, these findings show how racism affects the most intimate of relationships. Racism experienced by individuals in interracial relationships has implications for explaining racial dynamics at the meso level. Supplemental analysis, not shown, show that race-related everyday discrimination influences the mental health of Black respondents in interracial relationships more so than those in same-race relationships, though they experience everyday discrimination with similar prevalence. This suggests that the racism interracial couples experience is largely perpetuated in spaces they frequent (e.g., restaurants, workplaces, grocery stores, and community gatherings). Our findings might help explain why diversity and inclusion efforts fall short when they are not coupled with concerted efforts to address racist behavior and sentiments. In other words, diversity may exist in such spaces, but racist behavior persists and has negative consequences for people. A change in norms at the meso level is needed. More work is needed to document experiences of discrimination at the meso-level and to uncover the unconscious biases that people hold and the microaggressions experienced in such settings. Only then can we eradicate these inequities.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Erving recognizes funding from a grant from the National Institutes of Health (grant P30 AG015281) and the Michigan Center for Urban African American Aging Research.

Biographies

Amy Irby-Shasanmi is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at Indiana University–Purdue University, Indianapolis. As a scholar, she examines the health status and health care experiences of racial/ethnic minorities. To do this, in one line of work, she investigates the association between social relationships, social support, and well-being. In another line of research, she investigates health across the life course and last, she examines unfair treatment in medical settings.

Christy L. Erving is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology and the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Using theories, concepts, and perspectives from several research areas, her program of research focuses on clarifying and explaining status distinctions in health. Her primary research areas explore how race, ethnicity, gender, and immigrant status intersect to produce health differentials; the relationship between physical and mental health; psychosocial determinants of Black women’s health; and the Black-White mental health paradox.

Footnotes

Although the implicit assumption is that a person shares the same racial identity as their family members, this may not be the case. A person in an interracial relationship could be a member of a cross-racial adoption (and thus be a different race than family members) or one of the person’s relatives may have intermarried or dated someone of another race. Research shows that college students are more likely to interracially date if several of their own family members have dated interracially (Miller, Catalina et al. 2022).

References

- Alang Sirry, McAlpine Donna, and McClain Malcolm. 2021. “Police Encounters as Stressors: Associations with Depression and Anxiety across Race.” Socius 7. Retrieved September 8, 2022. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023121998128. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon Liat, and Gum Amber M.. 2011. “The Relationships between Major Lifetime Discrimination, Everyday Discrimination, and Mental Health in Three Racial and Ethnic Groups of Older Adults.” Aging and Mental Health 15(5):587–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr Ashley, and Simons Ronald. 2014. “A Dyadic Analysis of Relationship and Health: Does Couple-Level Context Condition Partner Effects?” Journal of Family Psychology 28(4):448–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell Gina Castle, and Hastings Sally O.. 2015. “Exploring Parental Approval and Disapproval for Black and White Interracial Couples.” Journal of Social Issues 71(4):755. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne, and Casper Lynne. 2001. Continuity and Change in the American Family. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger Niall, DeLongis Anita, Kessler Ronald, and Schilling Elizabeth. 1989. “Effects of Daily Stress on Negative Mood.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57(5):808–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo Lawrence. 2001. “Racial Attitudes and Relations at the Close of the Twentieth Century.” Pp. 264–301 in America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences, edited by Smelser N, Wilson WJ, and Mitchell F. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. 1997. “Rethinking Racism: Toward a Structural Interpretation.” American Sociological Review 62(3):465–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. 2003. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo, and Forman Tyrone A.. 2000. “‘I Am Not a Racist but …’: Mapping White College Students’ Racial Ideology in the USA.” Discourse & Society 11(1):50–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bratter Jenifer L., and Eschbach Karl. 2006. “‘What about the Couple?’ Interracial Marriage and Psychological Distress.” Social Science Research 35(4):1025–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bratter Jenifer, and Whitehead Ellen. 2018. “Ties That Bind? Comparing Kin Support Availability for Mothers of Mixed-Race and Monoracial Infants.” Journal of Marriage and Family 80(4):951–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Tony N. 2001. “Measuring Self-Perceived Racial and Ethnic Discrimination in Social Surveys.” Sociological Spectrum 21(3):377–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant Chalandra, and Conger Rand. 1999. “Marital Success and Domains of Social Support in Long-Term Relationships: Does the Influence of Network Members Ever End?” Journal of Marriage and Family 61(2):437–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant Chalandra, Conger Rand, and Meehan Jennifer. 2001. “The Influence of In-Laws on Change in Marital Success.” Journal of Marriage and Family 63(3):614–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant Chalandra M., Taylor Robert Joseph, Lincoln Karen D., Chatters Linda M., and Jackson James S.. 2008. “Marital Satisfaction among African Americans and Black Caribbeans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life.” Family Relations 57(2):239–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr Deborah, and Springer Kristen. 2010. “Advances in Families and Health Research in the 21st Century.” Journal of Marriage and Family 72(3):743–61. [Google Scholar]

- Childs Erica Chito. 2005. Navigating Interracial Borders: Black-White Couples and Their Social Worlds. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Trenette, Salas-Wright Christopher, and Whitfield Keith. 2015. “Everyday Discrimination and Mood and Substance Use Disorders: A Latent Profile Analysis with African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans.” Addictive Behaviors 40:119–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dainton Marianne. 1999. “African-American, European-American, and Biracial Couples’ Meanings for and Experiences in Marriage.” Pp. 147–67 in Communication, Race, and Family: Exploring Communication in Black, White, and Biracial Families, edited by Socha TJ and Diggs RC. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Erving Christy L. 2021. “The Effect of Stress Exposure on Major Depressive Episode and Depressive Symptoms among U.S. Afro-Caribbean Women.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 56(12):2227–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essed Philomena. 1991. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin Joe R., Vera Hernan, and Batur Pinar. 2000. White Racism: The Basics. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Forman Tyrone, and Lewis Amanda. 2015. “Beyond Prejudice? Young Whites’ Racial Attitudes in Post–Civil Rights America, 1976 to 2000.” American Behavioral Scientist 59(11):1394–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Gans Herbert J. 1999. “The Possibility of a New Racial Hierarchy in the Twenty-First Century United States.” Pp. 371–90 in The Cultural Territories of Race: Black and White Boundaries, edited by Lamont M. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden Noni, and Cunningham Jamila A.. 2009. “The Impact of Racial Discrimination and Coping Strategies on Internalizing Symptoms in African American Youth.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 38(4):532–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons Frederick, Gerrard Meg, Cleveland Michael, Wills Thomas, and Brody Gene. 2004. “Perceived Disorder and Substance Use in African American Parents and Their Children: A Panel Study.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86(4):517–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Noreen, Korenman Sanders, and Weinstein Rachel. 1995. “Marital Status and Health among the Elderly.” Social Science & Medicine 40(12):1717–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin Paula. 2003. “African American and European American Women’s Marital Well-Being.” Journal of Marriage and Family 65(3):550–60. [Google Scholar]

- Greif Geoffrey L., and Saviet Micah. 2020. “In-Law Relationships among Interracial Couples: A Preliminary View.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 30(5):605–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gullickson Aaron. 2006. “Black/White Interracial Marriage Trends, 1850–2000.” Journal of Family History 31(3):289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Kathleen Mullen, Lee Hedwig, and DeLeone Felicia Yang. 2010. “Marriage and Health in the Transition to Adulthood: Evidence for African Americans in the Add Health Study.” Journal of Family Issues 31(8):1106–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa Steven G., Wagner James, Torres Myriam, Duan Naihua, Adams Terry, and Berglund Patricia. 2004. “Sample Designs and Sampling Methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES).” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13(4):221–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson Andrea, and Brantley Mia. 2019. “Parents Just Don’t Understand: Parental Support, Religion and Depressive Symptoms among Same-Race and Interracial Relationships.” Religions 10(3):162–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks Raymond, and Tingley Dustin. 2011. “Causal Mediation Analysis.” Stata Journal 11(4):605–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann-Marriott Bryndl, and Amato Paul. 2008. “Relationship Quality in Interethnic Marriages and Cohabitation.” Social Forces 87(2):825–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hunte Haslyn, and Barry Adam. 2012. “Perceived Discrimination and DSM-IV-Based Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use Disorder.” American Journal of Public Health 102(12):e111–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston Ted. 2000. “The Social Ecology of Marriage and Other Intimate Unions.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 62(2):298–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ince Jelani. 2022. “‘Saved’ by Interaction, Living by Race: The Diversity Demeanor in an Organizational Space.” Social Psychology Quarterly 85(3):259–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson James S., Torres Myriam, Caldwell Cleopatra H., Neighbors Harold W., Nesse Randolph M., Taylor Robert Joseph, Trierweiler Steven J., et al. 2004. “The National Survey of American Life: A Study of Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Influences on Mental Disorders and Mental Health.” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13(4):196–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Pamela. 1997. “Role Occupancy and Minority Mental Health.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38(3):237–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judice Cheryl Y. 2008. Interracial Marriages between Black Women and White Men. Amherst, NY: Cambria. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald, McGonagle Katerine, Zhao Shanyang, Nelson Christopher, Huges Michael, Eshleman Suzann, Wittchen Hans-Ulrich, et al. 1994. “Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of DSM-III-R Psychiatric Disorder in the United States.” Archives of General Psychiatry 51(1):8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian Kyle D. 2002. “Dominant and Marginalized Discourses in Interracial Couples’ Narratives: Implications for Family Therapists.” Family Process 41(4):603–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian Kyle. 2013. Interracial Couples, Intimacy, and Therapy: Crossing Racial Borders. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal. 2005. “Negative Interaction and Heart Disease in Late Life: Exploring Variations by Socioeconomic Status.” Journal of Aging and Health 17(1):28–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger Nancy, Smith Kevin, Naishadham Deepa, Hartman Cathy, and Barbeau Elizabeth. 2005. “Experiences of Discrimination: Validity and Reliability of a Self-Report Measure for Population Health Research on Racism and Health.” Social Science & Medicine 61(7):1576–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger Rhiannon A., and Williams Kristi. 2011. “Consequences of Black Exceptionalism: Interracial Unions with Blacks, Depressive Symptoms, and Relationship Satisfaction.” Sociological Quarterly 52(3):400–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc Allen, Frost David M., and Wight Richard. 2015. “Minority Stress and Stress Proliferation among Same-Sex and Other Marginalized Couples.” Journal of Marriage and Family 77(1):40–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jennifer, and Bean Frank D.. 2004. “America’s Changing Color Lines: Immigration, Race/Ethnicity, and Multiracial Identification.” American Review of Sociology 30:221–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Sharon, and Edmonston Barry. 2005. “New Marriages, New Families: U.S. Racial and Hispanic Intermarriage.” Population Bulletin. Vol. 60. Washington, DC. Population Reference Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Tené, Cogburn Courtney, and Williams David. 2015. “Self-Reported Experiences of Discrimination and Health: Scientific Advances, Ongoing Controversies, and Emerging Issues.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 11:407–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard Lee A., Brien Michael J., and Waite Linda J.. 1995. “Premarital Cohabitation and Subsequent Marital Dissolution: A Matter of Self-Selection?” Demography 32(3):437–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Karen D., Taylor Robert Joseph, and Chatters Linda M.. 2012. “Correlates of Emotional Support and Negative Interaction Among African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans.” Journal of Family Issues 34(9):1262–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]