Abstract

Background: The increasing prevalence and subsequent mortality due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among Indian prisoners are often ignored by policymakers. This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to analyze the rising burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in Indian prisons and estimate the pooled prevalence of depression among Indian prisoners. Methods: A total 9 studies were chosen in accordance with PRISMA guidelines that investigated the burden of NCDs in Indian prisons and were published between January 2010 and August 2022. Statistical analysis was performed in STATA Version 16 software, and the funnel plot was used to identify publication bias. Results: A total of 167 articles were identified, and 9 were included in this analysis. The pooled prevalence of depression among prisoners was 48.78% (95% CI, 27.24–70.55%). According to the review, prisoners showed a significant prevalence of moderate to severe depression, dental caries, poor periodontal condition, and suicide ideation. This study is the first to analyze NCDs prevalence among Indian prisoners. Poor mental and dental health standards and the virtual absence of healthcare facilities necessitate governmental actions to boost inmates’ health. It is essential to develop preventative interventions for this extremely isolated and vulnerable group in addition to diagnosing and treating noncommunicable diseases. Conclusions: Our study findings will enable decision-makers to structure and develop appropriate preventative and curative programs for inmates’ general wellbeing.

Keywords: noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), prevalence, prisoners, prisoners health, mental health, prevention, systematic review

1. Introduction

A “prison” is any jail or place where inmates are kept permanently or temporarily on the state government’s special or general instructions, including all lands and structures that are connected to it. It does not, however, include any places designated as subsidiary jails or used to imprison inmates who are just under the police’s care [1]. Prisoners are disproportionately comprised of members of the most underprivileged member of society with poor health and untreated chronic illnesses. This specific group of society is a neglected part of society. Their health issues are rarely addressed. They are significantly more susceptible to illness than the rest of the population because their health status is influenced by both their surroundings and the prisons in which they are incarcerated. At the end of 2021, there were 1306 prisons in India, with a 113.8% occupancy rate [2]. However, 44.1% of inmates are between the ages of 18 to 30, while 42.9% are between the ages of 30–50. In 2020, 1642 natural deaths were reported in the prisons of India, out of which cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) accounting 31.1%, followed by 14.5% for lung ailments and 4.2% for various types of cancer [3]. To ensure that prison health services satisfy the needs of their prisoners, accurate estimates of the prevalence of chronic diseases must be obtained among the prisoner population as it continues to grow, along with the number of elderly inmates. It is well-recognized that chronic infectious diseases are more common in jails. Still, less is known about the prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among inmates, particularly in the context of India.

According to the WHO, the four major NCDs are diabetes, malignancies, chronic respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular diseases. NCD-related mortality accounts for around 3/4 of the global population, or 31.4 million people [4]. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are responsible for 60% of all mortality in India [5]. Even though NCDs impact people from all socioeconomic backgrounds, there are clear differences in the burden of NCDs, with those who are more vulnerable and have lower socioeconomic status were adversely affected [6].

There are no incidence or prevalence studies on NCDs in the prisoner population in India, and the available research appears to be limited to local descriptive health needs assessments. As a result, due to the dearth of scientific knowledge on the prevalence of NCDs in this vulnerable population, we conducted this analysis to assess the burden of non-communicable diseases among society’s most marginalized groups as well as the approaches to deal with the same.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

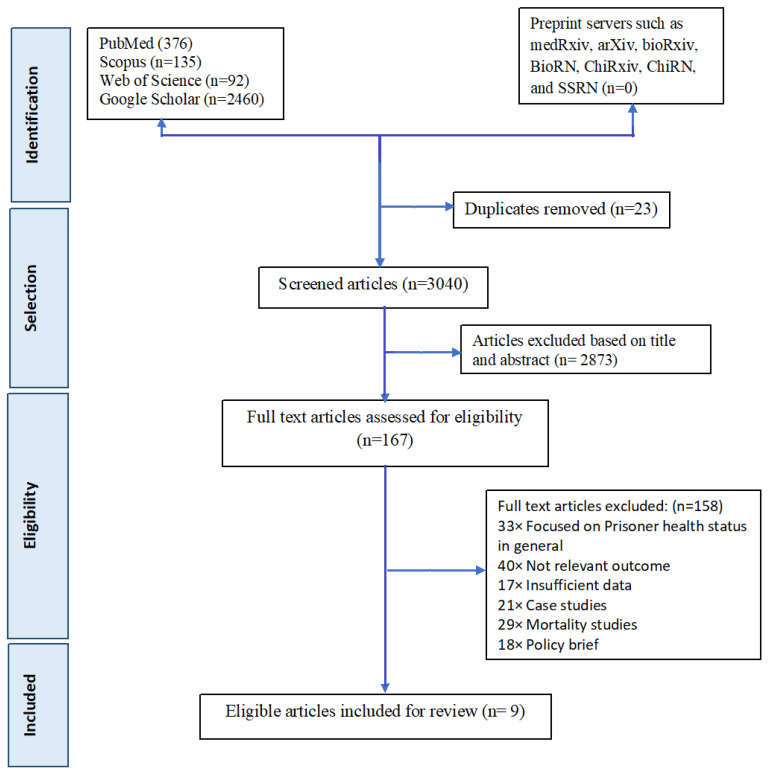

Four electronic databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus) were searched for publications published between 1 January 2010, and 1 January 2022. Initially, 376 articles from PubMed, 2460 articles from Google Scholar, 92 from Scopus, and 135 from Web of Science were discovered; however, 3040 items were reviewed, and after the exclusion of publications based on title and abstract, a comprehensive review of 167 articles were conducted, with 9 papers being selected for review.

The search terms included “NCDs,” “psychiatric disorders”, “cardiovascular diseases”, “Anaemia”, “Chronic respiratory illnesses”, “Oral disorders”, “Cancer” and “Musculo Skeletal disorder”, along with “prisoners”, “inmates”, and “India”. The essential phrases were used both separately and in conjunction with Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. To find relevant publications on the study’s title, MeSH terms with an asterisk were applied (Table A1). To handle citations and expedite the review process, articles were downloaded to Zotero. We looked for papers that were published between 2010 and 2022.

2.2. Data Extraction and Management

Two authors independently searched the papers. If there was a disagreement over the choice of an article, two of the co-authors discussed it and reached an agreement. If the two lead reviewers were discordant about the article’s eligibility, a third co-author was consulted to thoroughly assess the article and help to decide about the inclusion of the study. Reviewers ultimately discovered 9 articles that were relevant to the main topic. To maintain scientific accuracy in reporting searched publications, the Preferred Reporting Standard of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist was followed (Figure 1). The reviewers attentively read these 9 publications before tabulating their results.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for included studies in systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of NCDs among prisoners of India.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The COCOPOP (Condition, Context, and Population) paradigm was used to examine the eligibility of the included publications in this systematic review and meta-analysis [7]. Prisoners were the study population (POP), the condition (CO) was the prevalence of NCDs, and the context (CO) was only Indian studies. The lists of precise inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in Table A2.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Two (2) authors independently assessed the studies using the NHLBI-Quality assessment tool [8]. Table A3 displays the results for all investigations across all fourteen domains.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

By dividing the number of positive individuals by the total number of study participants, the prevalence of mental health disorders (Moderate-Severe depression) was determined. The I2 test was used to evaluate the heterogeneity of the studies used in this meta-analysis. The degree of variation between research is referred to as heterogeneity. According to the I2 values of less than 25%, 25–50%, and more than 50%, the studies’ heterogeneity was categorized as low, moderate, and high, respectively [9]. A significant amount of heterogeneity among the papers made up the meta-analysis. Therefore, a random-effect model with a 95% confidence interval was utilized to estimate the overall effect. p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant when performing the meta-analysis using STATA software (version 16, STATA Corp).

3. Results

This review covered 2676 prisoners from various Indian central and district level prisons. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of studies examining NCD among prisons in India. Most of the prisoners were male and belonged to the age group of 18–96 years. However, the socio-economic status of the majority of the prisoners belongs to the low-middle income group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of studies examining NCD among Prisons in India (N = 9).

| SL No | Author/YOP | Study Design | Sample | Prevalence | NCD Type | Age | Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||||||

| 1 | Tripathy et al., 2022 [10] | Cross-sectional | 105 | 27.6% | Depression | 18–65 | Male | |

| 2 | Kumar V et al., 2013 [11] | Cross-sectional | 118 | 33% | Psychiatric disorders | 19–66 | Male | Female |

| 3 | Ayirolimeethal A et al., 2014 [12] | Cross-sectional | 255 | 68.60% | Psychiatric disorders | 18–78 | Male | Female |

| 4 | Goyal SK et al., 2011 [13] | Cross-sectional | 500 | 23.80% | Psychiatric disorders | NA | Male | Female |

| 5 | Harave S V et al., 2021 [14] | Cross-sectional | 28 | 57.13% | Depression | 30–60 | Male | Female |

| 6 | Gupta R et al., 2013 [15] | Cross-sectional | 870 | 59.80% 58.60% 21.30% |

Oral Mucosal lesions Dental Fluorosis Dental caries |

18–85 | Male | Female |

| 7 | Arjun NT et al., 2014 [16] | Cross-sectional | 244 | 54.2% 14.8% 12.8% 35.80% |

Depression Schizophrenia Anxiety Disorder Oral mucosal lesions |

34–96 | Male | |

| 8 | Kumar D et al., 2013 [1] | Cross-sectional | 300 | 18% 84% 4% 7.33% |

Musculo skeletal disorder Anaemia Hypertension Dental Carries |

20–50 | Male | Female |

| 9 | Nagrale et al., 2014 [17] | Cross-sectional | 256 | 98.50% 82% |

Periodontal disease Dental Carries |

18–27 | Male | Female |

3.1. Mental Health Status in the Prisons

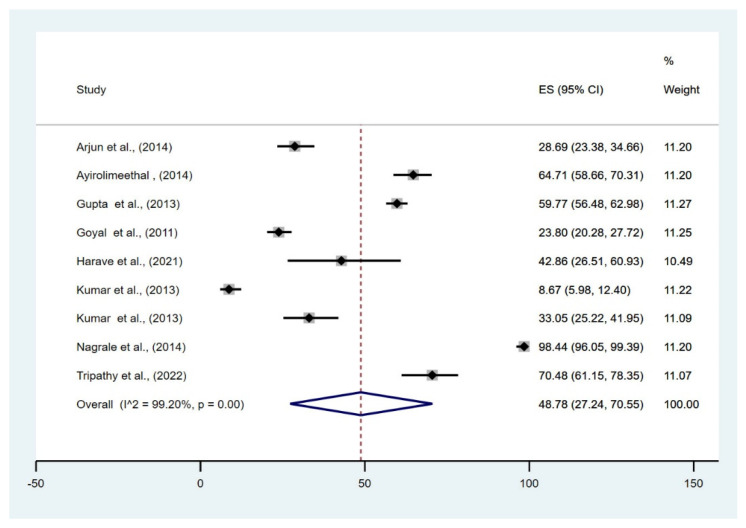

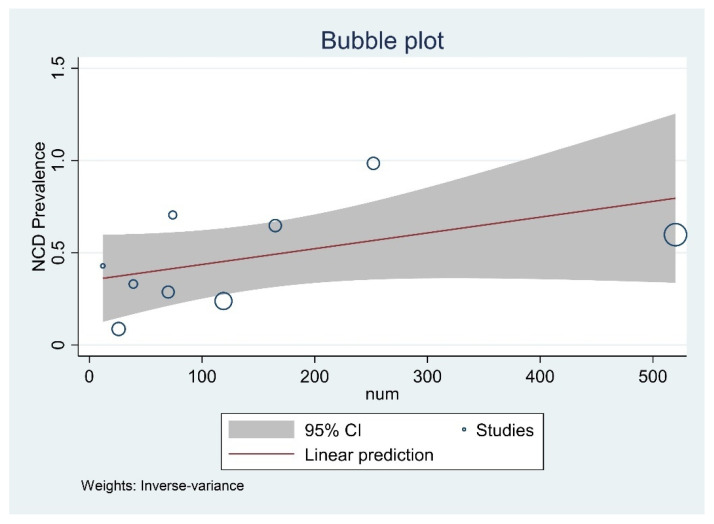

Six studies evaluated the prisoners’ mental health. The meta-analysis of the moderate-severe depression data reported that the pooled prevalence among prisoners was 48.78% (95% CI, 27.24–70.55%) across all district and central prisons of India. Since there was no heterogenicity included in the study, a fixed model was used (I2 = 99.20%, p = 0.001) (Figure 2). The bubble plot depicted that the studies that reported a higher prevalence of depression tend to have a larger sample size (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of pooled magnitude of NCDs among prisoners of India [1,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Figure 3.

Bubble plot with 95% Confidence interval of pooled prevalence of NCDs among prisoners of India.

The majority of the research papers reported that depression is the most common psychiatric disorder among inmates. For instance, a study reported that 23.8% of the imprisoned people at Central Jail in Amritsar had psychiatric illnesses other than substance misuse [13]. Among the prisoners, depression, schizophrenia-like symptoms, and suicidal ideation were the most often seen mental health issues. Inmates of an Odisha jail were found to have severe to moderate depression in 53.3% of cases, according to a study by Tripathy et al. [10]. According to this study, the educational status and level of social support from family members and other jail prisoners were the major determinants of depression behind bars. A similar study found that 33% of offenders in Kota’s major jail had psychiatric problems overall, with 6.7% having psychotic disorders, 16.1% having depressive disorders, and 8.5% having anxiety disorders [11]. Another study conducted in the district jail in Kozhikode, Kerala, discovered that 6.3% of prisoners had psychosis, 13.7% had adjustment issues, 4.3% had mood disorders, and 19.2% had antisocial personality disorder. A significant percentage of male prisoners (69.7%) were found to have a current mental health issue [12].

Another study, however, found that 0.67% of prisoners displayed signs of schizophrenia, while 1% of prisoners had severe depression and seizures [1]. This finding, supported by another study done in the Central Jail of Belgaum, represents that the majority of the prisoners had low depression; however, the prevalence of moderate to severe depression was 4.85%. In the early stages of conviction, depression (57.13%) was substantially more prevalent. Inmates who had been incarcerated for more than six years had a prevalence of 42.85%. In contrast, those who had been incarcerated for less than six years had a quite high prevalence of 57.13%, indicating that the length of the prison sentence was negatively connected with depression [14].

3.2. Publication Bias

Egger’s test for a regression intercept gave a p-value of 0.974, indicating no evidence of publication bias.

3.3. Prevalence of Oral Disease

4 studies assessed the oral health status of the inmates. Most of the studies reported that dental caries is the most common type of oral health issue faced by prisoners, followed by oral mucosal lesions and dental fluorosis. A study revealed a similar finding carried out in a Karnataka prison that 98.5% of people had periodontal disease, and 82.42% had dental caries. Most inmates (98%) did not receive any form of dental care while incarcerated. The study also relates prisoners’ dental issues to unhealthy habits, including smoking and the use of smokeless tobacco [18]. Another study conducted in the central jail of Bhopal among both the psychiatric and non-psychiatric inmates reported that the overall prevalence of oral lesions was 34.8%, comprising psychiatric inmates (39.3%) and non-psychiatric inmates (30.3%) [16].

Most of the studies depicted that majority of the prisoners have poor oral health, for instance, one of the studies conducted in the District Jail of Mathura reported that 79% of the prisoners had a poor periodontal condition and dental caries, followed by 59.8% inmates had pro-mucosal lesions. However, this study also reported that all the inmates demonstrated signs of dental fluorosis; 58.6% had mild, 27.8% had moderate, and 4.3% had severe fluorosis [15]. On the contrary, another study conducted in the Central Jail of Gulbarga city reported that only 7.33% of inmates had dental caries among all the prisoners [1].

3.4. Other NCDs

We did not find many studies that surveyed the prisoners’ major NCD status. We found just a single report which revealed that among the prisoners, the prevalence of anaemia, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, presbyopia, senile cataract and myopia, acute conjunctivitis, conductive deafness, otitis media, and circulatory system diseases was 84%, 2.33%, 1%, 3.67%, 2.67%,0.67%, 1.67%, 0.67% and 4%, respectively [1].

4. Discussion

Most research on the prevalence of NCDs and the treatment needs of prisoners has been conducted in Western countries. A thorough search of the literature revealed studies on the health status of prisoners in India. Still, the majority of these studies focused on the knowledge assessment of prisoners’ general health status, and very few studies were conducted on the burden of NCDs among prisoners, indicating that their health status is frequently neglected. Due to the dearth of available data, the present study aimed to evaluate the NCD burden among Indian inmates. This review of 9 studies provides a partial overview of the burden of NCDs among the inmates as a smaller number of studies addresses the issues of NCDs among the most neglected population of society. According to our findings, depression is the most common type of mental condition among prisoners. The main factors influencing this are a lack of social support and substance misuse. This finding is supported by another systematic review conducted in LMICs found that the estimated pooled prevalence of major depression among prisoners was 16% (11.7–20.8), which is considerably higher than the general population [19].

The study reported that the pooled prevalence among prisoners was 48.78% (95% CI, 27.24–70.55%) which is in line with another meta-analysis conducted in the prison of Ethiopia reported that the pooled prevalence of depression among Ethiopian prisoners was 44.45 (95% CI: 40.28, 48.61). The depression prevalence among Nepali prisoners also reported nearly similar results [20]. Our study also reported a low prevalence of schizophrenia among the prisoners, which is aligned with another study by Falissard et al., who found that 3.8% of French inmates had schizophrenia and 17.9% had major depression. In developing nations like India, the prevalence of mental diseases is low compared to Western nations [21].

A high proportion of significant mental illness among Indian prisoners may be attributed to the country’s poor community mental health-care facilities, which have yet to reach its socially disadvantaged and marginalized citizens. According to reports, low-resource environments have a higher occurrence of human rights violations involving detained people with mental health disorders, particularly those with psychotic illnesses [22].

This present study finds that among all oral problems, the prevalence of dental caries is more common among prisoners. These findings are in agreement with a multicentered oral health survey carried out in 2007–2008 in collaboration with WHO India and the Government of India’s Department of Health, which discovered that the prevalence of dental caries ranged from 23.0% to 71.5% in 12-year-old and from 48.1% to 86.4% in adults aged 35–45 years. On the other hand, the prevalence of dental caries among older adults aged 65 to 74 years ranged from 51.6–95.1%. The occurrence of periodontal disease in adults ranged from 15.32% to 77.9%, while in the aging population, it ranged from 19.9% to 96.1% [22]. However, Kumar et al. conducted a review that reported that, irrespective of their age and gender, most prisoners have periodontal disease and tooth decay. The study also concluded that the prison population exhibited a higher risk of tooth cavities and poor periodontal health than the general population [23].

This review finds that the anaemia prevalence among the prisoners was quite high compared to the general population, this finding is supported by a study conducted by Lokpo et al., which reported anaemia prevalence among the prisoners of Ho Central Prisons was 31.86% [24].

4.1. Recommendations

The present review yields several recommendations. Early detection, appropriate management, and prompt follow-ups are essential for the efficient monitoring and management of health conditions among prisoners. Delayed diagnosis and recently found outcomes may lead to increased morbidity, mortality, and the burden of the diseases. Due to barriers brought on by substance abuse and a lack of active follow-up, some people run the risk of not obtaining services even when they are diagnosed with an illness in time for treatment. Therefore, a pragmatic intervention program can be developed to provide preventive and curative care to prisoners. However, it is challenging for prisoners to obtain timely and effective medical care since most jails, especially those in developing countries, are understaffed and under-resourced.

Additionally, Indian prisoners are not well-aware of the need for medical care. The complexities in obtaining authorization to do medical examinations, treatments, and diagnostic tests inside prisons highlight the need for additional public health research in India. More data and research are required to determine the variables affecting the health status of the population in prison, not only in India but also in developing countries. Determining if incarceration or other systemic factors contribute more to the elevated risk of NCD is equally crucial. Furthermore, future research initiatives may include cross-sectional surveys to ascertain the prevalence and type of NCDs and risk factors related to them among prisoners. The appropriate timeframe for active case chasing among prisoners or follow-up screening after release should be determined. A follow-up study of the suggested service supply would also be valuable. It would also be beneficial to implement treatments to assess self-management support.

4.2. Limitations

One of the key limitations of this systematic review is the variation in the sample sizes of prisoners analyzed in the various studies. Even though we have included studies conducted in different regions of India, resulting in a geographically varied sample, it would have been assumed that the prevalence of oral health and mental health concerns would vary significantly due to differences in jail systems, access to counsellors, dentist, food habits, and data collection processes. Furthermore, the studies included in this review were all relied on observational data.

5. Conclusions

The epidemic has caused tremendous disruption in society, but it has also highlighted that “business as usual” falls short of meeting the unmet needs of disadvantaged people. This must be an opportunity to reset our society’s moral compass to ensure that historical injustices are mitigated, that everyone has access to health care, and that no one is left behind.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The adjusted search terms as per searched electronic databases.

| Database | No | Search Query | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | |||

| #1 | (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((NCD) OR (Non-communicable diseases)) OR (cancer)) OR (cardiovascular diseases)) OR (ischemic heart disease)) OR (neoplasm)) OR (mental health)) OR (depression)) OR (loneliness)) OR (oral health)) OR (periodontal status)) OR (oral cancer)) OR (diabetes)) OR (diabetes mellitus)) OR (anemia))) OR (chronic diseases)) OR (non-infectious diseases)) OR (hypertension)) OR (Atherosclerosis)) OR (stroke)) OR (Cerebrovascular Disorders)) OR (Myocardial Ischemia)) OR (Heart Failure)) OR (Heart Diseases)) OR (acute coronary syndrome)) OR (hypertensive heart disease)) OR (cardiac failure)) OR (myocardial infarction)) OR (HTN)) OR (vascular disease)) OR (double vessel disease)) OR (glucose tolerance)) OR (tumour)) OR (tumors)) OR (Neoplasms by Site)) OR (oral diseases)) OR (blood pressure)) OR (chronic kidney diseases)) OR (osteoarthritis)) OR (Alzheimer’s disease)) OR (cataracts)) OR (chronic lung illnesses)) OR (endocrine disorders)) OR (neuropsychiatric conditions)) OR (digestive diseases)) OR (rheumatoid arthritis)) OR (mental disorders)) OR (major depressive disorders)) OR (schizophrenia)) OR (anxiety disorders)) AND (India))) | 244,684 | |

| #2 | ((((((((((((((prisoners) OR (prison)) OR (jail)) OR (correctional settings)) OR (criminals)) OR (detention centre)) OR (gaol)) OR (detainee)) OR (incarceration)) OR (“correctional facilities” [All Fields])) OR (correctional settings)) OR (offender)) AND (India)))) | 1284 | |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 376 | |

| Scopus | |||

| #1 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (Non-communicable diseases) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (NCD) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (cardiovascular diseases) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (cancer) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (Diabetes)) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (Chronic lung diseases))AND (India))) | ||

| #2 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (prison) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (jail) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (detainee) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (incarceration) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (Inmates)) AND (India))) | ||

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 135 | |

| Web of Science | |||

| #1 | Non-communicable diseases (All Fields) or NCDs (All Fields) or cardiovascular diseases(All Fields) or cancer (All Fields) or Diabetes(All Fields) or Chronic lung diseases (All Fields) orAnemia (All Fields) or Psychiatric disorder (All Fields) or Oral Health (All Fields) AndIndia (All Fields) | ||

| #2 | Prison (All Fields) or Inmates (All Fields) or Detainee (All Fields)or incarceration (All Fields) AndIndia (All Fields) | ||

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | 92 | |

| Google Scholar | ((((((((((((((prisoners) OR (prison)) OR (jail)) OR (correctional settings)) OR (criminals)) OR (detention centre)) OR (gaol)) OR (detainee)) OR (incarceration)) OR (“correctional facilities” [All Fields])) OR (correctional settings)) OR (offender)) AND (India)))) | ||

| with at least one of the words | Non communicable disease | 25,200 | |

| with at least one of the words | Prisoners or inmate or jail or culprit or detainee or victim and India | 15,700 | |

| Final | 2460 | ||

Table A2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Male or Female Any length of time in prison Any age group |

Prisoners of war Recently released/parole Young offenders Secure Psychiatric Units Prison population sub-groups |

| Disease |

|

Communicable disease Trauma/accidents Studies focused only Dental Carries Prevalence of risk factors for disease (such as obesity, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking, alcohol, drug use etc) Pre-cancerous change (CIN, CIS etc) |

| Outcome | Prevalence measured from routine data sources such as; prison databases, medical notes, prescription lists, physical examinations, diagnostic tests, survey or self-reported | Prison as a risk factor for a disease in a wider population |

| Data is age-stratified or presented for those aged 50 years or older only | Mortality studies | |

| Study | Prevalence studies, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, case control studies, surveys | Qualitative, policy, opinion, case-studies, case-series studies |

| India Published between 2010–2022 English Language |

||

| Published and Un-published data | ||

Table A3.

Quality assessment of studies examining NCD among Prisons in India (N = 9) [1,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

| Authors/DOP | Tripathy et al., 2022 [10] | Kumar V et al., 2013 [11] | Ayirolimeethal A et al., 2014 [12] | Goyal SK et al., 2011 [13] | Harave S V et al., 2021 [14] | Dhanker k et al., 2013 [15] | Arjun NT et al., 2014 [16] | Kumar D et al., 2013 [1] | Nagrale et al., 2014 [17] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not Reported | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not Reported |

| 5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? | Yes | Yes | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| 6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured? | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| 7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Not Reported | Not Reported | Cannot Determine |

| 8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)? | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Cannot Determine | Yes | Cannot Determine | Yes |

| 9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| 11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| 13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| 14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Final remarks | Good | Good | Fair | Fair | Fair | Fair | Good | Good | Fair |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M., S.T. and B.K.P.; methodology, S.M., S.T., B.K.P. and V.K.C.; software, S.M. and B.K.P.; validation, S.M. and S.T.; resources, S.K.; data curation, R.K.S., S.M., S.T. and B.K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, B.K.P., B.N.-K. and V.K.C.; supervision, B.K.P.; project administration, B.K.P. and V.K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kumar S.D., Kumar S.A., Pattankar J.V., Reddy S.B., Dhar M. Health Status of the Prisoners in a Central Jail of South India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2013;35:373. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.122230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prison Statistics India 2020 | National Crime Records Bureau. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)]; Available online: https://ncrb.gov.in/en/prison-statistics-india-2020.

- 3.Prison Statistics India | National Crime Records Bureau. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)]; Available online: https://ncrb.gov.in/en/prison-statistics-india.

- 4.World Health Organization Noncommunicable Diseases. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- 5.Sub Centre H. Module for Multi-Purpose Workers (MPW)-Female/Male on Prevention, Screening and Control of Common Non-Communicable Diseases. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)]; Available online: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Module%20for%20Multi-Purpose%20Workers%20-%20Prevention%2C%20Screening%20and%20Control%20of%20Common%20NCDS_2.pdf.

- 6.World Health Organization Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018. World Health Organization. 2018; 223. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)]. Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274512.

- 7.Eriksen M.B., Frandsen T.F. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (Pico) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: A systematic review. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018;106:420–431. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantrell A., Croot E., Johnson M., Wong R., Chambers D., Baxter S.K., Booth A. Quality Appraisal of Included Studies. NIHR Journals Library; Southampton, UK: 2020. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553267/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsegaye R., Mulisa D., Wakuma B., Etafa W., Mosisa G., Turi E., Fetensa G., Oluma A., Seyoum D., Fekadu G., et al. The magnitude of depressive disorder and associated factors among prisoners in Ethiopia; implications for nursing care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2021;14:100289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2021.100289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tripathy S., Behera D., Negi S., Tripathy I., Behera R.M. Burden of depression and its predictors among prisoners in a central jail of Odisha, India. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Indian J. Psychiatry. 2022 64:295–300. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_668_21. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35859554/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar V., Daria U. Psychiatric morbidity in prisoners. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2013;55:366. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.120562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayirolimeethal A., Ragesh G., Ramanujam J., George B. Psychiatric morbidity among prisoners. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2014;56:150. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.130495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal S.K., Singh P., Gargi P.D., Goyal S., Garg A. Psychiatric morbidity in prisoners. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Indian J. Psychiatry. 2011 53:253–257. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.86819. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51847710_Psychiatric_morbidity_in_prisoners. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harave V.S., Nandakumar B.S., Guruprasad D.V. A cross-sectional study of depression among death row convicts from a south Indian state. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Kerala J. Psychiatry. 2021 34:35–39. Available online: https://kjponline.com/index.php/kjp/article/view/259. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta R., Dhanker K., Ingle N., Kaur N. Oral Health Status and Treatment Needs of Inmates in District Jail of Mathura City—A Cross Sectional Study. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];J. Oral Health Community Dent. 2013 7:24–32. doi: 10.5005/johcd-7-1-24. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334514731_Oral_Health_Status_and_Treatment_Needs_of_Inmates_in_District_Jail_of_Mathura_City_-_A_Cross_Sectional_Study. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arjun T.N., Sudhir H., Sahu R.N., Saxena V., Saxena E., Jain S. Assessment of oral mucosal lesions among psychiatric inmates residing in central jail, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India: A cross-sectional survey. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Indian J. Psychiatry. 2014 56:265–270. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.140636. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25316937/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagarale R.G., Nagarale G., Shetty P.J., Prasad K. Oral Health Status And Treatment Needs Of Prisoners Of Dharwad, India. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Int. J. Dent. Health Sci. 2014 1:849–860. Available online: https://nebula.wsimg.com/993b8ab58378793ec34f8130bd33fb92?AccessKeyId=44189AF8BC7E3D5EEFEF&disposition=0&alloworigin=1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baranyi G., Scholl C., Fazel S., Patel V., Priebe S., Mundt A.P. Severe mental illness and substance use disorders in prisoners in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Lancet Glob Health. 2019 7:e461–e471. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30539-4. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2214109X18305394/fulltext. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrestha G., Yadav D.K., Sapkota N., Baral D., Yadav B.K., Chakravartty A., Pokharel P.K. Depression among inmates in a regional prison of eastern Nepal: A cross-sectional study. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];BMC Psychiatry. 2017 17:348. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1514-9. Available online: https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-017-1514-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aishatu Y., Armiya U., Obembe A., Moses D.A., Tolulope O.A. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among inmates in Jos maximum security prison. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Open J Psychiatr. 2013 3:12–17. Available online: http://www.scirp.org/Html/3-1420130_27381.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jack H.E., Fricchione G., Chibanda D., Thornicroft G., Machando D., Kidia K. Mental health of incarcerated people: A global call to action. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 5:391–392. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30127-5. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2215036618301275/fulltext. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health And Family Welfare Govto National Oral Health Policy. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];2021 Available online: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/N_56820_1613385504626.pdf.

- 23.Kumar J., Collins A.C., Alam M.M. Oral Health Status of Prisoners in India: A Systematic Review. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Rev. Artic. Saudi J. Oral Dent. Res. 2017 2:140–146. Available online: https://saudijournals.com/media/articles/SJODR-26140-146.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lokpo S.Y., Osei-Yeboah J., Owiredu W.K., Agordoh P., Kortei N.K., Mensah D., Peter N., Ussher F.A., Ameke L.S., Dei Dika N., et al. Evaluation of dietary patterns and haematological profile of apparently healthy officers of the Central Prisons in the Ho municipality. A cross sectional study. [(accessed on 10 October 2022)];Sci. Afr. 2020 7:e00284. doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00284. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468227620300223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.