Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is characterized by exercise intolerance. Muscle blood flow may be reduced during exercise in PAH; however, this has not been directly measured. Therefore, we investigated blood flow during exercise in a rat model of monocrotaline (MCT)-induced pulmonary hypertension (PH). Male Sprague-Dawley rats (∼200 g) were injected with 60 mg/kg MCT (MCT, n = 23) and vehicle control (saline; CON, n = 16). Maximal rate of oxygen consumption (V̇o2max) and voluntary running were measured before PH induction. Right ventricle (RV) morphology and function were assessed via echocardiography and invasive hemodynamic measures. Treadmill running at 50% V̇o2max was performed by a subgroup of rats (MCT, n = 8; CON, n = 7). Injection of fluorescent microspheres determined muscle blood flow via photo spectroscopy. MCT demonstrated a severe phenotype via RV hypertrophy (Fulton index, 0.61 vs. 0.31; P < 0.001), high RV systolic pressure (51.5 vs. 22.4 mmHg; P < 0.001), and lower V̇o2max (53.2 vs. 71.8 mL·min−1·kg−1; P < 0.0001) compared with CON. Two-way ANOVA revealed exercising skeletal muscle blood flow relative to power output was reduced in MCT compared with CON (P < 0.001), and plasma lactate was increased in MCT (10.8 vs. 4.5 mmol/L; P = 0.002). Significant relationships between skeletal blood flow and blood lactate during exercise were observed for individual muscles (r = −0.58 to −0.74; P < 0.05). No differences in capillarization were identified. Skeletal muscle blood flow is significantly reduced in experimental PH. Reduced blood flow during exercise may be, at least in part, consequent to reduced exercise intensity in PH. This adds further evidence of peripheral muscle dysfunction and exercise intolerance in PAH.

Keywords: blood flow, exercise, PAH, pulmonary hypertension, skeletal muscle

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a devastating progressive disorder in which thrombosis, proliferation, inflammation, and remodeling of the lung vasculature lead to a narrowing of pulmonary arteries and subsequent right ventricular (RV) pressure overload, dilation, and ultimately failure (1). Significant strides have been made in understanding complex PAH pathophysiology; however, patient prognosis remains poor (2) and a cure remains elusive. Importantly, even with optimal pharmacological treatment, patients with PAH still suffer from reduced quality of life and a profound exercise intolerance (3–5). This dysfunction is characterized by lower maximal aerobic capacity (6, 7), compromised pulmonary function (8, 9), reduced muscle strength and power (10–13), and early-onset dyspnea and fatigue (7, 14). As such, interest in the connection between PAH pathophysiology and exercise limitation has increased in recent years, revealing complex central and peripheral abnormalities because of the disease (15).

Previous work has shown that compromised RV function, including an inability to maintain stroke volume and subsequent left ventricular (LV) filling limits cardiac output at the onset of exercise in PAH (16). In addition, it has been observed that patients display chronotropic incompetence (17), RV/LV dyssynchrony (18–20), and reduced myocardial contractility (21). In addition, increased pulmonary vascular resistance reduces RV cardiac output [Waxman (8)], and compromised respiratory dynamics (22–24) have been implicated as contributors to exercise intolerance in the disease. Importantly, abnormalities specific to skeletal muscle have also been shown to limit exercise performance in both patients with PAH and animal models. Upper and lower body muscle strength and endurance are reduced (11, 12, 25–27), and these limitations have been directly associated with functional performance. In addition, skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction and reliance on nonoxidative metabolism have been identified both in patient studies (12, 28) and supported by our group and others in animal models (29, 30). Finally, several investigators have shown that reduced capillarity and microcirculation in skeletal muscle blunts exercise capacity (13, 27, 31) indicating morphological changes that develop as a consequence of disease.

Although it is clear that multiple factors play a role in limiting exercise in PAH, it is still uncertain whether exercise limitations in PAH are due to reduced blood flow to skeletal muscle. Adequate blood flow is essential to the maintenance of exercise, however, to the best of our knowledge, skeletal muscle blood flow has not been directly measured in PAH. Indeed, interrogating the role of oxygen delivery to exercising muscle during exercise has recently been identified as an important knowledge gap that requires further investigation (15). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to characterize directly measured blood flow in an animal model of PH. We hypothesized that in rats with experimental PH, skeletal muscle blood flow would be reduced at both rest and during moderate-intensity exercise.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical Approval

The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Indiana University, which is in compliance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (∼200 g; Charles River Chicago, IL) were used in this study. Only male rats were studied because the model used [i.e., monocrotaline (MCT) injection] does not reliably produce a PH phenotype in the female rat (32), likely due to differing metabolism of MCT in the liver (33, 34). All animals were housed in pairs in the Indiana University animal facility and fed standard rat chow and water ad libitum. The rats were maintained at an ambient temperature of 21°C–24°C with a 12 h-12 h dark-light cycle.

PH Induction and Experimental Groups

PH was induced via a single MCT injection [60 mg/kg, sq in sterile phosphor-buffered saline (PBS), Sigma Aldrich] that reliably produces a severe PAH phenotype at ∼4 wk postinjection (35). Control animals (CON) received vehicle (saline, sc). Animals were then grouped as MCT (n = 23) and CON (n = 16) for phenotyping, with sub-groups from those (MCT, n = 8 and CON, n = 7) included in blood flow analysis. The timeline for PH induction and subsequent measures are described in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Study protocol. MCT, monocrotaline; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure.

Treadmill Familiarization and Aerobic Capacity Testing

As running is a skilled activity for rats, familiarization to the rodent motorized treadmill was performed for 4 days before exercise testing. The familiarization protocol involved 4 × 5 min runs that gradually increased treadmill speed (8–12 m/min) and incline (0°–15°). These inclines and speeds are similar to those experienced during maximal aerobic testing. Familiarization runs were limited to minimize chronic training effects before baseline testing. A mild electric stimulus at the back of the treadmill chamber promoted the learning of running behavior, and the ability of the rat to run successfully was documented through this familiarization period. “Cueing,” including the use of verbal encouragement, treadmill lane taps, and group running were used to promote consistent running toward the front of the treadmill belt. If a rat contacted the stimulus three consecutive times without the ability to recover to the front of the treadmill belt, the familiarization session was terminated.

Maximal oxygen consumption (V̇o2max) was measured using an indirect calorimetry system paired with the motorized rodent treadmill (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Gas analyzer calibrations were conducted before testing using standardized gas mixtures (20.97%–20.98% O2, 0.044% CO2 measured to within 0.01% of the target concentration—Praxair, Indianapolis, IN). Baseline rate of oxygen consumption (V̇o2) was monitored for 3–5 min until stabilization, and this was recorded as “resting V̇o2” an incremental treadmill running protocol [modified from Kemi et al. (36)] was then administered, using 3 min stages as follows: 8 m/min at 5° (warm up), 8 m/min at 15°, 9.8 m/min at 15°, and 11.6 m/min at 15°, etc., with the speed continuing to increase by 1.8 m/min every 3 min until test completion. Flow rate to the chamber was 4.34 L/min, and V̇o2 was measured at 20 s intervals throughout. The test was terminated when V̇o2 plateaued despite increasing workload, or if the rat was unable to maintain running after three consecutive electrical stimuli without recovery to the front of the treadmill belt. The highest V̇o2 measured in the minute following test completion was recorded as V̇o2max and expressed relative to body weight (mL·min−1·g−1). The final V̇o2max test was used to determine relative exercise intensities for blood flow analysis.

Voluntary Wheel Running

For measurement of volitional wheel running activity, rats were familiarized for 24 h in a cage equipped with a computer-monitored running wheel (Lafayette Instruments, model 80850S Scurry Rat Activity Wheel), with wheel revolutions recorded by 86115 Scurry Sensor/Counter, 86130 Interface, and 86165 Scurry Software, connected to a computer interface for complete data collection (3 s sample rate), analysis, and charting. Voluntary running distance (in m) was subsequently measured over a single 12 h dark cycle.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed 1 day before blood flow testing. Rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in an induction box and then placed on the heated platform with a nose cone and maintained at 1%–2%. The hair was clipped over the chest, and fine hair was removed using a depilatory cream. The skin was cleaned with wet gauze squares. Ultrasonic gel was placed over the chest for the echo procedure, and an ultrasonic probe of ∼6 cm by 8 cm was placed in contact with the gel. Two-dimensional short-axis and long-axis images were acquired by using a high-resolution ultrasound system as previously described (37). Upon determination of all echocardiographic end points, rats were recovered from anesthesia and placed into a heated cage to recover. All images were obtained by a blinded sonographer.

Surgical Preparation and Blood Flow Measurement

Blood flow to skeletal muscle was measured via injection of fluorescent microspheres as initially described by Ishise et al. (38) and Glenny et al. (39) during and after moderate intensity running (50% V̇o2max) for MCT and CON. Rats were anesthetized by inhaled isoflurane and then orotracheally intubated with a catheter (14 ga) and mechanically ventilated using a tidal volume of 6 mL/kg and a rate of 65–70 breaths/min. End expiratory pressures were at 3–4 cmH2O by a water overflow on the expiratory limb of the ventilator. The rats were placed on a servo-controlled heated tray that maintains the animal temperature at 37°C. Animals were shaved (total abdominal and thoracic surfaces), and the skin was cleansed with Betadine and ethanol (ETOH). The animal was fixed to the operating table with adhesive tape and covered with a sterile drape with a hole allowing access to the surgical area. The animal was administered carprofen (5 mg/kg: 0.1–0.5 mL, sq) before surgery. The right carotid artery and caudal (tail) artery were cannulated via cutdowns through small skin incisions. Arterial and airway pressures were measured continuously. Normal saline boluses (10 mL/kg) were given at the beginning of the procedure to replace blood loss from surgery, blood sampling, and ongoing insensible losses during surgery. After placement, tubing was tunneled subcutaneously between the scapulae, and tied in with ∼25 cm of the external line access for microsphere delivery and reference blood sampling in carotid and caudal lines. Incisions were closed using silk suture for muscle layers and monofilament suture for skin. After surgery was completed, animals were placed back in the cage for recovery (minimum >1 h) in preparation for exercising and resting blood flow measures. To mitigate the potential anticipatory response demonstrated in trained rats (40) exercise measures were carried out before those at rest. In both conditions, fluorescent microspheres were prepared for infusion by sonicating for >5 min and vigorously vortexing for >1 min. The caudal artery line was flushed with 0.5 mL saline to encourage effective bleed-back of reference blood. Running was initiated at a moderate intensity as determined by calculating 50% V̇o2max as described. After 3 min of running at the predetermined intensity to establish a steady state, fluorescent microspheres (n = ∼400,000, Red 580/620, Molecular Probes) were injected over 10 s into the carotid cannula. The line was subsequently flushed with 0.5 mL heparinized saline to ensure all spheres were successfully injected. Ten seconds before microsphere infusion, collection of a reference blood sample from the caudal cannula was begun using a motorized syringe withdrawal pump (Kent Scientific, CT). Blood was collected for 60 s at a constant rate of 1 mL/min. After the exercise measures, the rat rested for 1-h before determination of resting blood flow. At this time, a second microsphere infusion of a different color (n = ∼400,000, Yellow-Green, 500/545, Molecular Probes) was performed in the same manner.

Plasma Lactate

Plasma lactate was measured using a small sample of arterial blood from the caudal line used for reference blood sampling. Approximately 10 µL of blood was withdrawn after the reference blood sample and immediately analyzed using a portable lactate analyzer (Lactate Pro, Sports Resource Group), previously used to measure blood lactate in exercising rats (41, 42).

Invasive Hemodynamics

Immediately after resting blood flow and lactate measures, rats were anesthetized by inhalation of isofluorane-O2 mixture (5%), orotracheally intubated, and mechanically ventilated under isofluorane maintenance (2%). The left carotid artery was cannulated with PE-50 tubing and the right internal jugular vein with a 2-F Millar catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX). Surgery was performed on a servo-controlled heated tray that maintained the animal temperature at 37°C. Recordings of pulmonary and systemic pressures were achieved within 30 min following transfer out of the treadmill chamber. Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) were assessed in room air and recorded simultaneously.

Tissue Processing

Immediately after hemodynamic measurements, rats were euthanized under anesthesia (5% isofluorane-O2 mixture) via exsanguination and bilateral pneumonectomy as a secondary means of euthanasia, which also allowed for immediate access to the diaphragm and heart muscles. Right ventricular hypertrophy was assessed by measuring the Fulton index [weight of the RV divided by weight of the left ventricle plus septum (S); RV/(LV + S)]. Sections of RV and muscle [biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius (GA), soleus (SL), rectus femoris (RF), vastus lateralis (VL)] were then snap-frozen in liquid N2 then stored at −80°C for later biochemical analysis and imaging. Samples from the same muscle groups were collected from the contralateral leg for blood flow quantification. Muscles were weighed and placed in 5% ethanolic potassium hydroxide for 48 h for tissue degradation. Samples were regularly vortexed to ensure full degradation. Reference blood samples collected during exercise and at rest were processed in the same fashion. After degradation, samples were reverse filtered through 5-μm polyamide mesh filters (Sterlitech). Each filter was carefully placed into a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube (Thermo Fisher), and 1 mL of cellosolve acetate (2-ethoxyethyl acetate, 98%, Sigma Aldrich) was added to each of the tubes to degrade microspheres and expose the fluorescence. At 1 h tubes were vortexed to ensure maximum exposure to cellosolve acetate. This was repeated at 2 h. Samples of 100 μL from each tube were then loaded in duplicate into a 96-well plate in preparation for spectroscopic analysis.

Blood Flow Quantification

All fluorescence measurements were made using a SpectraMax i3x microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Red fluorescence (representing exercising flow) was measured at an excitation of 580 nm and an emission of 620 nm, and yellow-green fluorescence (representing resting flow) was measured at an excitation of 500 nm and an emission of 545 nm. Tissue blood flow was calculated using Eq. 1 (39, 43):

| (1) |

Blood flow units are calculated (presented as mL·min−1·100 g−1 of tissue; at rest) by dividing the calculated flow by the recorded muscle sample weight at the time of harvest. Exercising blood flows are presented as relative to power output at time of microsphere infusion (mL·min−1·100 g−1/W). Power was calculated using Eq. 2:

| (2) |

Bilateral kidney flow was used as a measure of adequate microsphere mixing and subsequent uniform systemic blood flow in vivo, with a discrepancy of >20% in flow across right and left kidneys resulting in that animal being disregarded from blood flow analysis.

Capillarization

To determine if muscle capillarization differed between MCT and CON rats, immunofluorescent staining was performed with frozen sections from two different sampled muscles, the predominantly type I (slow twitch) soleus, and the predominantly type II (fast twitch) extensor digitorum longus (EDL). The midsection of frozen muscles was cut, embedded in OCT (Fisher Scientific), and frozen at −80°C until subsequent tissue sectioning. Muscles were sectioned at 8 µm using a cryostat (Reichert-Jung Frigocut 2800) at −20°C and mounted on Superfrost Plus Microscope Slides (Fisher Scientific). Slides were submerged in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. They were subsequently air-dried and stored at –80°C in preparation for staining. After three washes in phosphor-buffered saline with Tween (PBS-T, Fisher Scientific) sections were incubated for 48 h at 4°C with an antibody cocktail containing 1:500 dilution wheat germ agglutinin (W6748 WGA-oregon green 488 conjugate 5 mg, Thermo Fisher), 1:75 dilution lectin (isolectin GS-IB4 alexaFluor 594 conjugate, Thermo Fisher) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) vehicle (Thermo Fisher). Negative controls were processed similarly, with antibodies replaced by incubation in TBS only. Slides were washed three times in PBS-T, after which coverslips containing DAPI ProLong Gold (Fisher Scientific) for nuclei staining were mounted to slides and fixed using Biotium Covereslip Sealant (Biotium, CA). Tissue sections were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 inverted fluorescence microscope (NY). Three different fields were imaged in each tissue section (9 per muscle sample). Green, red, and blue images were taken at their optimal exposure times and exported to ImageJ (NIH). A technician blinded to group assignments counted myocyte and capillary numbers in each field and calculated capillary-to fiber ratio for all muscle sections.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (San Diego, CA). Data are presented as means ± SE. Differences at α level of 0.05 (P < 0.05) were considered statistically significant. In addition to analyzing blood flow measured within each harvested skeletal muscle, a “compiled blood flow” variable was also created by averaging resting flow and separate exercising flow in individual muscles for each rat. Parametric T-testing for comparison between MCT and CON groups was performed for the following measurements: echocardiography [stroke volume, cardiac output, cardiac index, RV thickness, pulmonary acceleration time (PAT), and total peripheral resistance index (TPRi)], RV hypertrophy (Fulton Index, RV weight) RVSP, RVSP/MAP, body weight and aerobic capacity (V̇o2max), and exercise behavior (voluntary wheel running) and capillarization. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by group assignment and muscle was used to interrogate differences in blood flow. Pearson product correlations were used to determine relationships between blood flow and metabolic/disease measures.

RESULTS

PH Phenotype

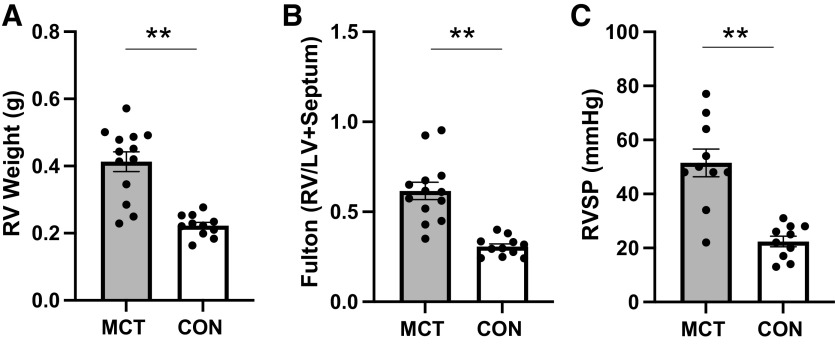

Four weeks after MCT injection, rats showed a PH phenotype (Fig. 2, A–C) as expected, demonstrated by an increased RV weight (0.22 ± 0.01 vs. 0.41 ± 0.03, P = <0.001), increased Fulton index (0.62 ± 0.05 vs. 0.31 ± 0.02, P = <0.001), and increased RVSP (51.5 ± 5 vs. 22.4 ± 2 mmHg, P = <0.001) compared with CON. Echocardiography revealed elevated RV thickness and significant declines in cardiac function in MCT with reduced stroke volume, cardiac output, cardiac index, pulmonary acceleration time, and a significantly increased pulmonary resistance index (Table 1).

Figure 2.

A–C: PH phenotype as evidenced by increased RV weight (0.22 ± 0.01 vs. 0.41 ± 0.03), increased Fulton index (0.62 ± 0.05 vs. 0.31 ± 0.02), and increased RVSP (51.5 ± 5 vs. 22.4 ± 2 mmHg) in MCT (n = 12–13) compared with CON (n = 11). **P ≤ 0.001. CON, control; MCT, monocrotaline; RV, right ventricle; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure.

Table 1.

Echocardiographic measurements

| CON (n = 16) | MCT (n = 16) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RV thickness, m | 1.53 ± 0.1 | 2.27 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Stroke volume, µL | 264 ± 11 | 218 ± 13 | 0.011 |

| Cardiac output, mL/min | 86 ± 4 | 65 ± 5 | 0.001 |

| Cardiac index, mL·min−1·g−1 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.008 |

| PAT, ms | 32 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 0.004 |

| TPRi | 43 ± 6 | 77 ± 16 | 0.02 |

| HR | 331 ± 7 | 308 ± 7 | 0.02 |

CON, control; HR, heart rate; MCT, monocrotaline; PAT, pulmonary acceleration time; RV, right ventricle.

Body weight, treadmill maximal aerobic capacity (V̇o2max), and 12-h volitional wheel running distance were not different between groups pre-MCT/vehicle injection (P > 0.05); however, at final time point, body weight (335.3 ± 44.4 vs. 400.3 ± 38.8 g, P = <0.001) and V̇o2max (53.1 ± 15.3 vs. 72.2 ± 8 mL/kg−1/min−1, P = <0.001) were significantly lower for the MCT (n = 18) rats compared with their CON (n = 14) counterparts and tended to be lower in wheel running distance (498 ± 550 vs. 912 ± 638 m, P = 0.08), consistent with the expected phenotype. Furthermore, MCT demonstrated a significantly greater decline in V̇o2max from pre- to final time points when compared with CON (−13.1 ± 1.9% vs. −38.9 ± 7.8%, P = 0.003).

Blood Flow

Figure 3 demonstrates blood flow at rest and when expressed relative to power output during exercise across all muscles for MCT and CON. At rest, no significant differences are seen between groups, however, during exercise, skeletal muscle blood flow was significantly reduced in MCT compared with CON (P ≤ 0.001).

Figure 3.

Resting (A) and exercising (B) blood flow in MCT (n = 7) vs. CON (n = 8). At rest, no significant difference is seen between groups (P = 0.35). When expressed relative to power output during exercise, blood flow is significantly lower in MCT vs. CON (P = <0.001). BF, biceps femoris; CON, control; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; GA, gastrocnemius; MCT, monocrotaline; RF, rectus femoris, SL, soleus; ST, semitendinosus; TA, tibialis anterior; VL, vastus lateralis.

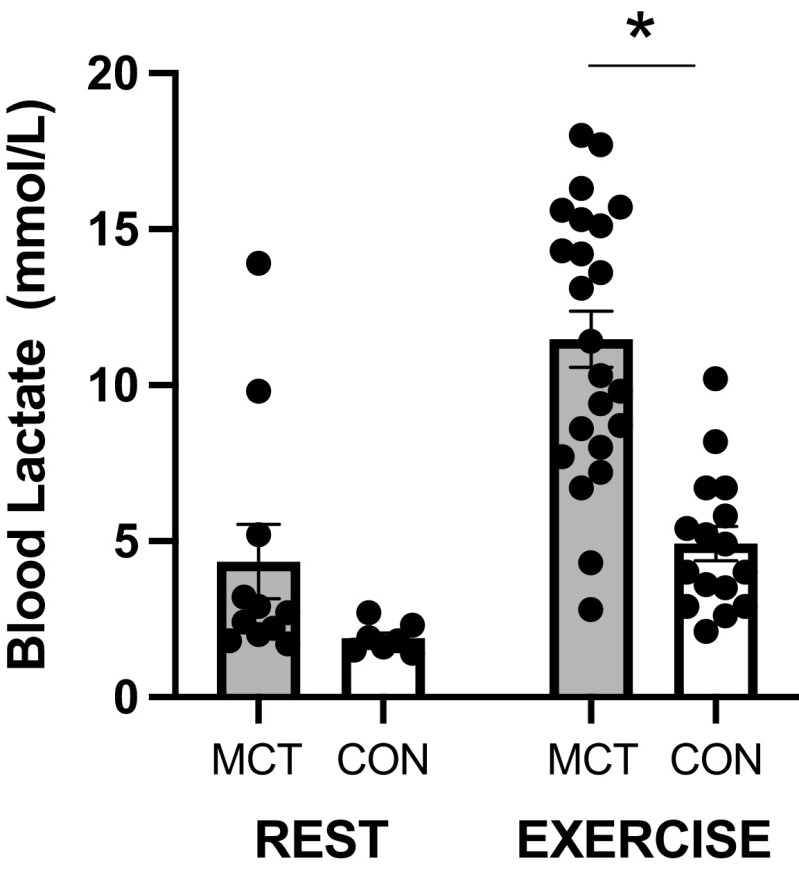

Metabolism

Blood lactate (Fig. 4) was not statistically different at rest in MCT compared with CON (P > 0.05); however, during exercise, blood lactate was significantly elevated in MCT rats versus CON (P = 0.002).

Figure 4.

Evidence of altered metabolism during exercise via increased blood lactate in MCT (n = 23) vs. CON (n = 16). *P ≤ 0.05. CON, control; MCT, monocrotaline.

Exercising blood lactate was inversely correlated to exercising blood flow in the EDL, tibialis anterior, and soleus (Fig. 5, A–C), and tended to be related to reduced blood flow in other muscles sampled as well, including the gastrocnemius (r = −0.53, P = 0.08) and biceps femoris (r = −0.57, P = 0.05). When expressed as a compiled value for all skeletal muscles tested (average of eight muscles), a significant inverse association for blood flow with blood lactate during exercise was also observed (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Exercising blood lactate was inversely correlated to exercising blood flow in the EDL (A), tibialis anterior (B), and soleus (C), and a significant inverse association for blood flow with blood lactate during exercise was also observed when blood flow is expressed as a compiled value for all skeletal muscles (D) (n-12). EDL, extensor digitorum longus; SL, soleus; TA, Tibialis anterior.

Although there was no association for skeletal muscle blood flow at rest with any indicators of disease severity, there was a tendency for blood flow during exercise to be lower in animals with a more severe PH phenotype, such as with higher Fulton index (r = −0.48, P = 0.06) and lower cardiac output (r = 0.59, P = 0.09).

Capillarization

There were no significant differences in capillarization between MCT and CON for either of the two skeletal muscles sampled, the predominantly type I muscle soleus and the predominantly type II muscle EDL (Table 2, Fig. 6).

Table 2.

Capillary density

| Muscle | CON, n = 8–9 (Capillaries per Myocyte) |

MCT, n = 9–13 (Capillaries per Myocyte) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDL | 0.96 ± 0.0 | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 0.12 |

| Soleus | 1.42 ± 0.1 | 1.45 ± 0.1 | 0.85 |

CON, control; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; MCT, monocrotaline.

Figure 6.

Representative images of immunofluorescent staining of muscle tissue imaged at ×10 magnification. Capillaries (yellow, as overlay of green and red), myocyte membrane (glycoproteins, green), vasculature (lectin, red), nuclei (DAPI, blue) in soleus muscle sections. CON, control; MCT, monocrotaline.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate skeletal muscle blood flow at rest and during exercise in a PH animal model. We determined that rats with MCT-induced PH and right heart disease have reduced skeletal muscle blood flow during moderate intensity exercise when compared with healthy controls, supporting previous work in both left heart failure (44–46) and preliminary investigations into the hemodynamic responses to exercise in patients with PAH (13, 47). In addition, we observed a significant relationship between reduced skeletal blood flow and increased blood lactate during exercise. These findings add to the growing body of evidence demonstrating the significance of muscle maladaptation in this disease.

The relative contributions of both central and peripheral dysfunction as they relate to impaired performance in PAH continue to be debated. Undoubtedly, RV compromise attenuates cardiac output response to exercise stress (16–21); however, peripheral manifestations of the disease are now well established as additional contributors to observed performance decrements. Previous work demonstrates that exercise intolerance can occur independently of cardiac responses in PAH (13, 23), and improvements in physical function may occur without significant central changes (48–50), supporting an important role of the periphery. We propose that reduced skeletal muscle blood flow may pose a potentially important limitation to exercise tolerance as well.

A prior report of impaired skeletal muscle blood flow in an MCT rat model of cardiac disease included only resting measures and was limited to two muscles (43). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to directly measure skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise in an experimental PAH model and to demonstrate a robust deficiency across several muscle groups. It is well established that at the onset of exercise, blood flow and, therefore, oxygen delivery are increased to meet the rising metabolic demands of skeletal muscle (46, 51), and there is a growing body of evidence that this response is compromised in PAH. Most notably, it has been demonstrated that circulatory abnormalities at the skeletal muscle level may contribute to a reduced exercise performance. Evidence of microcirculatory loss (27), reduced oxygen saturation/extraction (13, 31), and slower hyperemia responses (47) have all been suggested as peripheral mechanisms restricting exercise tolerance in PAH. Our data obtained from directly measured blood flow in a PAH model provides further evidence of circulatory dysfunction as a peripheral contributor to disease sequelae.

Blood flow limitations during exercise have been characterized to a greater extent in left heart failure, and although absolute values for blood flow are somewhat variable, the data tend to support the findings in this study. Drexler et al. (44) demonstrated a significant reduction to the gastrocnemius during maximal exercise in an infarct model of heart failure. Later work in a similar model noted that rats more severely afflicted demonstrated the most profound decrements in blood flow to exercising muscles (45). Interestingly, our data closely mirrors this classic work as we describe higher resting blood flow in the soleus muscle in comparison to the quadriceps and ankle flexors/extensors. Although these early studies advanced a novel insight into exercise intolerance in left heart failure, they have since been supported by multiple investigations into exercises responses in the disease, comprehensively reviewed by Poole et al. (46) and Hirai et al. (52). It has been shown that central limitations in heart failure only partially explain a reduction in blood flow to working muscles in LHF. Although a reduced cardiac output may decrease the speed and magnitude of blood supply to skeletal muscle at the onset of exercise, systemic vasoconstriction, vascular stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, inflammatory markers, and reduced NO bioavailability are all postulated as factors culminating in compromised exercising blood flow in the disease (46).

In PAH, angiogenic deficiencies and microcirculatory loss have been implicated in reduced exercise tolerance. Potus et al. (27) described a significant correlation between downregulated angiogenic signaling in the quadriceps muscles of patients with PAH and exercise intolerance. In line with these findings, reduced capillarization was demonstrated in the RV of an MCT rat model, secondary to downregulation of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 pathway (53). This would indicate a microcirculatory myopathy that extends to both the myocardium and peripheral muscle in PAH. Although reduced skeletal muscle capillarity could potentially provide an explanation for reduced blood flow, we did not see a significant difference in capillary numbers between MCT and CON rats. Although we report slightly lower capillary-to-fiber ratios than previously described (54), we note greater capillarization of the primarily type I soleus compared with type II EDL (55). Regardless, in each muscle MCT did not induce rarefaction at the myocyte level. This contrasts the aforementioned report of reduced capillarity in the RV after 6 wk post-MCT injection (53). It is possible that more time is needed post-PH induction to see such changes at the skeletal muscle level, or more significantly, that this model may not represent muscle abnormalities as seen in patients with PAH. With that said, our results would seem to contradict that of Potus et al. (27) who showed that exercise intolerance was related to microcirculatory dysfunction in patients, concomitant with a capillary loss in quadriceps muscle. However, compelling evidence would seem to suggest that microcirculatory function rather than morphology better explains the control of blood flow to skeletal muscle during exercise (56). Indeed, a recent study in an MCT rat has demonstrated muscle oxygen delivery is compromised via reduced red blood cell flux, velocity, and decreased capillary supporting flow in resting skeletal muscle (57), further indicating the importance of hemodynamic control as a contributor to muscle dysfunction in the disease. As such, future mechanistic investigations aimed at explaining reduced muscle blood flow during exercise in this model should likely focus here.

There was a tendency for exercising blood flow to relate to disease measures, including RV hypertrophy and cardiac output. It should be noted while cardiac output was measured at rest via echocardiography, it may be the case that an exercise stimulus is required to elucidate the connection between central and peripheral dysfunction in this model. Prior evidence has shown that exercise stress (such as that carried out in an incremental exercise test) may be required to identify physiological abnormalities that are central to disease progression, and may have an important diagnostic role in the clinical setting (58, 59). Indeed, the presence of increased RV pressures during exercise have been suggested as a precursor to resting PH (60); however, the variable nature of responses to exercise in healthy individuals has made defining an “exercise pulmonary hypertension” an ongoing challenge (61). However, it is clear the integrated nature of the exercise response can shed light on a host of clinically relevant factors, including the metabolic, ventilatory, and cardiovascular abnormalities present in the disease (4), and ultimately determine the severity of the disease and patient prognosis (62).

We have demonstrated a significant relationship between reduced skeletal muscle blood flow and increased blood lactate accumulation during exercise in a PH rat model. Indeed, the high lactates in combination with low muscle blood flows would suggest a severe heart failure phenotype, further supported by the aforementioned decline in cardiac function and significant RV hypertrophy in MCT rats. We suggest that our results may in fact underestimate the reduced blood flow and lactate correlation, which is significantly strengthened when any potentially errant rat data is removed from the analysis (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, a well-established hallmark of the abnormal exercise response in PAH is a metabolic disturbance (12, 15, 28). Moreover, it has previously been shown that high levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase indicative of metabolic abnormality independently predicts functional status in patients with PAH (63). Lactate and hydrogen ions accumulate in the blood as a result of several interrelated mechanisms, including a reliance on nonaerobic glycolysis, conversion of pyruvate to lactate, and reduced systemic clearance via lactate oxidation contributing to the onset of fatigue [comprehensively reviewed by Poole et al. (64)]. Previous work in PAH has shown an early accumulation of lactate relative to exercise intensity (4), indicating an ineffective switch from aerobic to anaerobic means of ATP production. Several mechanisms may explain this phenomenon in PAH, including blunted cardiac response to exercise (7, 8, 16, 26) and muscle adaptations that compromise oxidative metabolism (10–12, 28, 29). Our results suggest an association between cardiovascular maladaptation’s driven by disease and a metabolic disturbance that may limit exercise capacity in PAH. Further investigation should therefore interrogate the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in exercise limitation for this population.

We note limitations in this study. Although the monocrotaline model has been widely used in pulmonary hypertension research for decades, the mechanisms by which pulmonary pressure and hemodynamic abnormalities arise may not adequately replicate human disease. In addition, there is compelling evidence that multiple organ systems are impacted by MCT administration. Some 50 years ago Roth et al. (65) noted injuries to the liver, kidneys, and lungs of rats exposed to MCT in drinking water. More recently, this has been supported by a number of studies reporting vascular changes in the lungs of MCT-treated rats, leading to the idea of an “MCT-syndrome” proposed by Gomez-Arroyo et al. (66). As such, we are unable to definitively state that the skeletal muscle changes are solely a result of PH modeling without a more direct effect of MCT on skeletal muscle morphology and function. Indeed, we recommend the further study of MCT on skeletal muscle tissue more broadly, as undoubtedly this model will continue to be implemented in PH animal studies. Crucially, MCT does not reliably induce a PH phenotype in the female rat (32). As such, future investigations should assess alternative models, with the inclusion of female animals highly encouraged. Although our results demonstrate blood flow was lower in MCT animals relative to power output during exercise, this difference may be partially due to different absolute exercise intensities between groups. Finally, although we have demonstrated reduced skeletal muscle blood flow in an MCT rat, the mechanisms behind this deficit remain to be elucidated. We have shown that capillary rarefaction in this model is likely not a determining factor, hence future work should focus on vascular function as it is related to muscle perfusion.

In conclusion, we have shown that in a PAH animal model, skeletal blood flow is significantly reduced during moderate-intensity exercise. These findings can be linked to previous work in this area, most notably that tissue oxygen supply and extraction are reduced in patients with PAH. We further observed an association between exercising blood flow and lactate accumulation, suggesting that both central and peripheral factors may lead to metabolic disturbance and exercise limitation in the disease. These findings lend weight to the developing idea that pharmacologic, exercise, and/or nutritional strategies specifically aimed at combating skeletal muscle dysfunction in PAH are warranted and may ultimately provide a novel adjuvant treatment method.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grant R15 HL121661 (to M. B. Brown).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.M.L., T.L., and M.B.B. conceived and designed research; G.M.L., A.D.T., D.A.G., A.J.F., and M.B.B. performed experiments; G.M.L., A.R.C., and M.B.B. analyzed data; G.M.L., T.L., A.R.C., and M.B.B. interpreted results of experiments; G.M.L., A.R.C., and M.B.B. prepared figures; G.M.L. and M.B.B. drafted manuscript; G.M.L., T.L., A.R.C., and M.B.B. edited and revised manuscript; G.M.L., A.D.T., D.A.G., A.J.F., T.L., A.R.C., and M.B.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Galiè N, Palazzini M, Manes A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: from the kingdom of the near-dead to multiple clinical trial meta-analyses. Eur Heart J 31: 2080–2086, 2010. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, Jaïs X, Cottin V, Prevot G, Picard F, de Groote P, Jevnikar M, Bergot E, Chaouat A, Chabanne C, Bourdin A, Parent F, Montani D, Simonneau G, Humbert M, Sitbon O. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 50: 1700889, 2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00889-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Babu AS, Arena R, Myers J, Padmakumar R, Maiya AG, Cahalin LP, Waxman AB, Lavie CJ. Exercise intolerance in pulmonary hypertension: mechanism, evaluation and clinical implications. Expert Rev Respir Med 10: 979–990, 2016. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2016.1191353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neder JA, Ramos RP, Ota-Arakaki JS, Hirai DM, D'Arsigny CL, O'Donnell D. Exercise intolerance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. The role of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12: 604–612, 2015. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-558CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tran DL, Lau EMT, Celermajer DS, Davis GM, Cordina R. Pathophysiology of exercise intolerance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respirology 23: 148–159, 2018. doi: 10.1111/resp.13141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arena R, Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Myers J, Guazzi M. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: an evidence-based review. J Heart Lung Transplant 29: 159–173, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun XG, Hansen JE, Oudiz RJ, Wasserman K. Exercise pathophysiology in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 104: 429–435, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hc2901.093198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waxman AB. Exercise physiology and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 55: 172–179, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deboeck G, Niset G, Lamotte M, Vachiéry JL, Naeije R. Exercise testing in pulmonary arterial hypertension and in chronic heart failure. Eur Respir J 23: 747–751, 2004. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00111904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Batt J, Ahmed SS, Correa J, Bain A, Granton J. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 50: 74–86, 2014. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0506OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Man FS, van Hees HW, Handoko ML, Niessen HW, Schalij I, Humbert M, Dorfmüller P, Mercier O, Bogaard HJ, Postmus PE, Westerhof N, Stienen GJ, van der Laarse WJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Ottenheijm CA. Diaphragm muscle fiber weakness in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 1411–1418, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0354OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mainguy V, Maltais F, Saey D, Gagnon P, Martel S, Simon M, Provencher S. Peripheral muscle dysfunction in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax 65: 113–117, 2010. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.117168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malenfant S, Potus F, Mainguy V, Leblanc E, Malenfant M, Ribeiro F, Saey D, Maltais F, Bonnet S, Provencher S. Impaired skeletal muscle oxygenation and exercise tolerance in pulmonary hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc 47: 2273–2282, 2015. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. D'Alonzo GE, Gianotti LA, Pohil RL, Reagle RR, DuRee SL, Fuentes F, Dantzker DR. Comparison of progressive exercise performance of normal subjects and patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest 92: 57–62, 1987. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malenfant S, Lebret M, Breton-Gagnon É, Potus F, Paulin R, Bonnet S, Provencher S. Exercise intolerance in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insight into central and peripheral pathophysiological mechanisms. Eur Respir Rev 30: 200284, 2021. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0284-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holverda S, Gan CT, Marcus JT, Postmus PE, Boonstra A, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Impaired stroke volume response to exercise in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 1732–1733, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Provencher S, Chemla D, Hervé P, Sitbon O, Humbert M, Simonneau G. Heart rate responses during the 6-minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 27: 114–120, 2006. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00042705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Badagliacca R, Papa S, Valli G, Pezzuto B, Poscia R, Reali M, Manzi G, Giannetta E, Berardi D, Sciomer S, Palange P, Fedele F, Naeije R, Vizza CD. Right ventricular dyssynchrony and exercise capacity in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 49: 1601419, 2017. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01419-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hill AC, Maxey DM, Rosenthal DN, Siehr SL, Hollander SA, Feinstein JA, Dubin AM. Electrical and mechanical dyssynchrony in pediatric pulmonary hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 31: 825–830, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marcus JT, Gan CT, Zwanenburg JJ, Boonstra A, Allaart CP, Gotte MJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Interventricular mechanical asynchrony in pulmonary arterial hypertension: left-to-right delay in peak shortening is related to right ventricular overload and left ventricular underfilling. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 750–757, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spruijt OA, de Man FS, Groepenhoff H, Oosterveer F, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Bogaard HJ. The effects of exercise on right ventricular contractility and right ventricular-arterial coupling in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191: 1050–1057, 2015. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2271OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aslan GK, Akinci B, Yeldan I, Okumus G. Respiratory muscle strength in patients with pulmonary hypertension: the relationship with exercise capacity, physical activity level, and quality of life. Clin Respir J 12: 699–705, 2018. doi: 10.1111/crj.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Breda AP, Pereira de Albuquerque AL, Jardim C, Morinaga LK, Suesada MM, Fernandes CJ, Dias B, Lourenço RB, Salge JM, Souza R. Skeletal muscle abnormalities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. PloS One 9: e114101, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saglam M, Vardar-Yagli N, Calik-Kutukcu E, Arikan H, Savci S, Inal-Ince D, Akdogan A, Tokgozoglu L. Functional exercise capacity, physical activity, and respiratory and peripheral muscle strength in pulmonary hypertension according to disease severity. J Phys Ther Sci 27: 1309–1312, 2015. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bauer R, Dehnert C, Schoene P, Filusch A, Bärtsch P, Borst MM, Katus HA, Meyer FJ. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Med 101: 2366–2369, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Manders E, Rain S, Bogaard HJ, Handoko ML, Stienen GJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Ottenheijm CA, de Man FS. The striated muscles in pulmonary arterial hypertension: adaptations beyond the right ventricle. Eur Respir J 46: 832–842, 2015. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02052-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Potus F, Malenfant S, Graydon C, Mainguy V, Tremblay E, Breuils-Bonnet S, Ribeiro F, Porlier A, Maltais F, Bonnet S, Provencher S. Impaired angiogenesis and peripheral muscle microcirculation loss contribute to exercise intolerance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190: 318–328, 2014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0383OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malenfant S, Potus F, Fournier F, Breuils-Bonnet S, Pflieger A, Bourassa S, Tremblay E, Nehmé B, Droit A, Bonnet S, Provencher S. Skeletal muscle proteomic signature and metabolic impairment in pulmonary hypertension. J Mol Med (Berl) 93: 573–584, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brown MB, Chingombe TJ, Zinn AB, Reddy JG, Novack RA, Cooney SA, Fisher AJ, Presson RG, Lahm T, Petrache I. Novel assessment of haemodynamic kinetics with acute exercise in a rat model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Exp Physiol 100: 742–754, 2015. doi: 10.1113/EP085182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Enache I, Charles AL, Bouitbir J, Favret F, Zoll J, Metzger D, Oswald-Mammosser M, Geny B, Charloux A. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction precedes right ventricular impairment in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Mol Cell Biochem 373: 161–170, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1485-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tolle J, Waxman A, Systrom D. Impaired systemic oxygen extraction at maximum exercise in pulmonary hypertension. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40: 3–8, 2008. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318159d1b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bal E, Ilgin S, Atli O, Ergun B, Sirmagul B. The effects of gender difference on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 32: 766–774, 2013. doi: 10.1177/0960327113477874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lafranconi WM, Huxtable RJ. Hepatic metabolism and pulmonary toxicity of monocrotaline using isolated perfused liver and lung. Biochem Pharmacol 33: 2479–2484, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kasahara Y, Kiyatake K, Tatsumi K, Sugito K, Kakusaka I, Yamagata S-I, Ohmori S, Kitada M, Kuriyama T. Bioactivation of monocrotaline by P-450 3A in rat liver. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 30: 124–129, 1997. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199707000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hessel MH, Steendijk P, den Adel B, van der Laarse A. Characterization of right ventricular function after monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in the intact rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 291: H2424–H2430, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00369.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kemi OJ, Loennechen JP, Wisloff U, Ellingsen O. Intensity-controlled treadmill running in mice: cardiac and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93: 1301–1309, 2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00231.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown MB, Neves E, Long G, Graber J, Gladish B, Wiseman A, Owens M, Fisher AJ, Presson RG, Petrache I, Kline J, Lahm T. High-intensity interval training, but not continuous training, reverses right ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction in a rat model of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R197–R210, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00358.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ishise S, Pegram BL, Yamamoto J, Kitamura Y, Frohlich ED. Reference sample microsphere method: cardiac output and blood flows in conscious rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 239: H443–H449, 1980. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.4.H443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Glenny RW, Bernard S, Brinkley M. Validation of fluorescent-labeled microspheres for measurement of regional organ perfusion. J Appl Physiol (1985) 74: 2585–2597, 1993. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.5.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Armstrong RB, Hayes DA, Delp MD. Blood flow distribution in rat muscles during preexercise anticipatory response. J Appl Physiol (1985) 67: 1855–1861, 1989. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.5.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu SS, Lau CP, Tung YF, Huang SW, Chen YH, Shih HC, Tsai SC, Lu CC, Wang SW, Chen JJ, Chien EJ, Chien CH, Wang PS. Lactate stimulates progesterone secretion via an increase in cAMP production in exercised female rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Physiol 271: E910–E915, 1996. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.5.E910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kato M, Kurakane S, Nishina A, Park J, Chang H. The blood lactate increase in high intensity exercise is depressed by Acanthopanax sieboldianus. Nutrients 5: 4134–4144, 2013. doi: 10.3390/nu5104134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vescovo G, Ceconi C, Bernocchi P, Ferrari R, Carraro U, Ambrosio GB, Libera LD. Skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain expression in rats with monocrotaline-induced cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Relation to blood flow and degree of muscle atrophy. Cardiovasc Res 39: 233–241, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Drexler H, Faude F, Höing S, Just H. Blood flow distribution within skeletal muscle during exercise in the presence of chronic heart failure: effect of milrinone. Circulation 76: 1344–1352, 1987. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.6.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Musch TI, Terrell JA. Skeletal muscle blood flow abnormalities in rats with a chronic myocardial infarction: rest and exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H411–H419, 1992. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Poole DC, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Musch TI. Muscle oxygen transport and utilization in heart failure: implications for exercise (in)tolerance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1050–H1063, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00943.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dimopoulos S, Tzanis G, Manetos C, Tasoulis A, Mpouchla A, Tseliou E, Vasileiadis I, Diakos N, Terrovitis J, Nanas S. Peripheral muscle microcirculatory alterations in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot study. Respiratory Care 58: 2134–2141, 2013. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chan L, Chin LMK, Kennedy M, Woolstenhulme JG, Nathan SD, Weinstein AA, Connors G, Weir NA, Drinkard B, Lamberti J, Keyser RE. Benefits of intensive treadmill exercise training on cardiorespiratory function and quality of life in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Chest 143: 333–343, 2013. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fox BD, Kassirer M, Weiss I, Raviv Y, Peled N, Shitrit D, Kramer MR. Ambulatory rehabilitation improves exercise capacity in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Card Fail 17: 196–200, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mereles D, Ehlken N, Kreuscher S, Ghofrani S, Hoeper MM, Halank M, Meyer FJ, Karger G, Buss J, Juenger J, Holzapfel N, Opitz C, Winkler JRG, Herth FFJ, Wilkens H, Katus HA, Olschewski H, Grünig E. Exercise and respiratory training improve exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with severe chronic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 114: 1482–1489, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.618397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sarelius I, Pohl U. Control of muscle blood flow during exercise: local factors and integrative mechanisms. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 199: 349–365, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hirai DM, Musch TI, Poole DC. Exercise training in chronic heart failure: improving skeletal muscle O2 transport and utilization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H1419–H1439, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00469.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sutendra G, Dromparis P, Paulin R, Zervopoulos S, Haromy A, Nagendran J, Michelakis ED. A metabolic remodeling in right ventricular hypertrophy is associated with decreased angiogenesis and a transition from a compensated to a decompensated state in pulmonary hypertension. J Mol Med (Berl) 91: 1315–1327, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Poole DC, Mathieu-Costello O, West JB. Capillary tortuosity in rat soleus muscle is not affected by endurance training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 256: H1110–H1116, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Armstrong RB, Phelps RO. Muscle fiber type composition of the rat hindlimb. Am J Anat 171: 259–272, 1984. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001710303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Laughlin MH, Davis MJ, Secher NH, van Lieshout JJ, Arce-Esquivel AA, Simmons GH, Bender SB, Padilla J, Bache RJ, Merkus D, Duncker DJ. Peripheral circulation. Compr Physiol 2: 321–447, 2012. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schulze KM, Weber RE, Horn AG, Colburn TD, Ade CJ, Poole DC, Musch TI. Effects of pulmonary hypertension on microcirculatory hemodynamics in rat skeletal muscle. Microvasc Res 141: 104334, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2022.104334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hsu S, Houston BA, Tampakakis E, Bacher AC, Rhodes PS, Mathai SC, Damico RL, Kolb TM, Hummers LK, Shah AA, McMahan Z, Corona-Villalobos CP, Zimmerman SL, Wigley FM, Hassoun PM, Kass DA, Tedford RJ. Right ventricular functional reserve in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 133: 2413–2422, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Farina S, Correale M, Bruno N, Paolillo S, Salvioni E, Badagliacca R, Agostoni P; “Right and Left Heart Failure Study Group” of the Italian Society of Cardiology. The role of cardiopulmonary exercise tests in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 27: 170134, 2018. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0134-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Medarov BI, Jogani S, Sun J, Judson MA. Readdressing the entity of exercise pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Med 124: 65–71, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, Williams PG, Souza R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 53: 1801913, 2019. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Paolillo S, Farina S, Bussotti M, Iorio A, PerroneFilardi P, Piepolil MF, Agostoni P. Exercise testing in the clinical management of patients affected by pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur J Prev Cardiol 19: 960–971, 2012. doi: 10.1177/1741826711426635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hu EC, He JG, Liu ZH, Ni XH, Zheng YG, Gu Q, Zhao ZH, Xiong CM. High levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase correlate with the severity and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Exp Ther Med 9: 2109–2113, 2015. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Poole DC, Rossiter HB, Brooks GA, Gladden LB. The anaerobic threshold: 50+ years of controversy. J Physiol 599: 737–767, 2021. doi: 10.1113/JP279963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Roth RA, Dotzlaf LA, Baranyi B, Kuo CH, Hook JB. Effect of monocrotaline ingestion on liver, kidney, and lung of rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 60: 193–203, 1981. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gomez-Arroyo JG, Farkas L, Alhussaini AA, Farkas D, Kraskauskas D, Voelkel NF, Bogaard HJ. The monocrotaline model of pulmonary hypertension in perspective. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L363–L369, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00212.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]