Keywords: aorta, macrophages, T cells, vascular remodeling, Windkessel function

Abstract

We have shown that excessive endothelial cell stretch causes release of growth arrest-specific 6 (GAS6), which activates the tyrosine kinase receptor Axl on monocytes and promotes immune activation and inflammation. We hypothesized that GAS6/Axl blockade would reduce renal and vascular inflammation and lessen renal dysfunction in the setting of chronic aortic remodeling. We characterized a model of aortic remodeling in mice following a 2-wk infusion of angiotensin II (ANG II). These mice had chronically increased pulse wave velocity, and their aortas demonstrated increased mural collagen. Mechanical testing revealed a marked loss of Windkessel function that persisted for 6 mo following ANG II infusion. Renal function studies showed a reduced ability to excrete a volume load, a progressive increase in albuminuria, and tubular damage as estimated by periodic acid Schiff staining. Treatment with the Axl inhibitor R428 beginning 2 mo after ANG II infusion had a minimal effect on aortic remodeling 2 mo later but reduced the infiltration of T cells, γ/δ T cells, and macrophages into the aorta and kidney and improved renal excretory capacity, reduced albuminuria, and reduced evidence of renal tubular damage. In humans, circulating Axl+/Siglec6+ dendritic cells and phospho-Axl+ cells correlated with pulse wave velocity and aortic compliance measured by transesophageal echo, confirming chronic activation of the GAS6/Axl pathway. We conclude that brief episodes of hypertension induce chronic aortic remodeling, which is associated with persistent low-grade inflammation of the aorta and kidneys and evidence of renal dysfunction. These events are mediated at least in part by GAS6/Axl signaling and are improved with Axl blockade.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY In this study, a brief, 2-wk period of hypertension in mice led to progressive aortic remodeling, an increase in pulse wave velocity, and evidence of renal injury, dysfunction, and albuminuria. This end-organ damage was associated with persistent renal and aortic infiltration of CD8+ and γ/δ T cells. We show that this inflammatory response is likely due to GAS6/Axl signaling and can be ameliorated by blocking this pathway. We propose that the altered microvascular mechanical forces caused by increased pulse wave velocity enhance GAS6 release from the endothelium, which in turn activates Axl on myeloid cells, promoting the end-organ damage associated with aortic stiffening.

INTRODUCTION

Research in hypertension has traditionally focused on abnormalities of arterioles that modulate systemic vascular resistance. Altered mechanics of larger central arteries, particularly the aorta, are increasingly recognized, however, as having a major role in the genesis of end-organ damage in hypertension (1). The primary function of large arteries is to store elastic energy as they distend during systole and to use this energy to augment blood flow as they recoil during diastole. This capacitance or Windkessel function allows healthy central arteries to decrease the workload on the heart and improve flow to critical organs such as the heart, brain, and kidney (2, 3). In diverse conditions, including aging, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and cigarette smoking, the central arteries remodel and their Windkessel function declines (4–7). It is thought that stiffening of the central arteries increases transmission of systolic pressure into the microcirculation, thereby imparting increased pulsatility in the smaller resistance vessels. Indeed, Rosenberg et al. (8) recently showed that transmission of pulsatile blood flow into intracerebral vessels is markedly increased during resistance exercise in older adults compared with younger individuals, and this correlates with pulse wave velocity. Likewise, Suri et al. (9) found an inverse relationship between pulse wave velocity and both white matter integrity and cognitive performance in 542 subjects in the Whitehall II study. Importantly, these findings are relevant to renal damage. Woodward et al. (10) used mediation analysis to show that the renal artery pulsatile index seems to be an important determinant of reduced renal vascular cortical volume and albuminuria. Likewise, in the Jackson Heart study, arterial stiffness and increased aortic pulsatility were associated with reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria in African Americans (11).

An important consideration regarding the end-organ damage associated with aortic stiffening is whether this is simply due to mechanical injury caused by increased pulsatility or whether there are molecular signals released from vascular cells that promote dysfunction and injury. If the latter were true, then blockade of such a pathway might prevent consequent disease. In this regard, we have recently shown that increased cyclical stretch of endothelial cells leads to release of the protein growth arrest specific 6 (GAS6), which in turn activates the tyrosine kinase Axl on monocytes (12). This action of GAS6/Axl signaling initiates a cascade of events that promotes renal and vascular inflammation and worsens blood pressure elevation (13). Axl activation was found to cause transformation of monocytes to a dendritic cell-like phenotype. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of Axl prevented elevations in systolic blood pressure and accumulation of renal immune cells.

In the present study, we established and characterized a mouse model of long-term aortic remodeling caused by a brief period of hypertension and examined the effect of Axl blockade on consequent target organ, specifically renal damage. Our findings suggest a new therapeutic approach to prevent and possibly reverse consequences of aortic remodeling following an episode of hypertension.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice at 12 wk of age were randomly selected from their cages and assigned to sham or angiotensin II (ANG II) infusion groups. A 2-wk episode of hypertension was induced by subcutaneous implantation of osmotic minipumps to deliver ANG II at a rate of 490 ng/kg/min. Multiple prior studies from our laboratory have shown that this dose of ANG II consistently raises blood pressure to 160 to 165 mmHg (12–21) but does not cause aortapathies such as aortic dissection observed with higher doses. Sham animals were implanted with osmotic minipumps containing vehicle. Following 2 wk, the mice were reanesthetized and the osmotic minipumps were removed. Blood pressure (BP) was measured using the noninvasive tail cuff method by a blinded observer. A subset of mice was randomized to be treated with an Axl inhibitor (R428 at 25 mg/kg in DMSO + dH2O; drinking water; MedChem Express), whereas others were treated with DMSO vehicle beginning 2 mo after either sham or ANG II infusion. Mice were provided with normal chow and treated in their cages with either R428 or vehicle added to their water for the ensuing 2 mo. At the time points indicated, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, their chest immediately opened, a 23-gauge needle inserted into the left ventricle, and the right atrium opened. Heparinized saline was then infused into the left ventricle at a pressure of 110 mmHg until the right atrial effluent was cleared of blood. For studies using immunohistochemistry, the mice were subsequently perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde at this pressure. All experimental procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Flow Cytometry

To quantify immune cell infiltration, the descending thoracic and abdominal aortas were minced with scissors, and the kidneys were mechanically dissociated using a single gentleMACS C tube dissociator system (Miltenyi). These tissues were then incubated at 37°C for 30 min with collagenase D (2 mg/mL) and DNAse I (100 µg/mL) in RPMI 1640 medium with 5% FBS. Kidney homogenates were filtered through a 70-mm cell strainer and centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min, and the pellet was then resuspended in 3 mL of Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer (Invitrogen Cat. No. 00-4333-57) for 3 min according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resultant single-cell suspensions were then washed and stained for the indicated surface markers. Flow cytometry was performed using Cytek Aurora (Cytek, Bethesda, MD), and data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc) software. Dead cells were excluded using live/dead staining, and gates were established using fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls. The absolute number of infiltrating cells of each type was calculated using counting beads added for each analysis. Results were expressed as the number of cells per aorta or kidney. Antibodies used and their fluorophore conjugates are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for flow cytometry

| Antibody | Fluorochrome | Clone | Company | Catalog No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zombie NIR fixable viability kit | Zombie NIR | BioLegend | 423106 | |

| Anti-CD4 | PerCP-Cy5.5 | GK1.5 | BioLegend | 100434 |

| Anti-IFNγ | BV421 | XMG1.2 | BioLegend | 505829 |

| Anti-F4/80 | PE-Cy5 | BM8 | BioLegend | 123112 |

| Anti-γ/δ TCR | APC-Cy7 | GL3 | BioLegend | 118143 |

| Anti-CD3 | BV510 | 145-2C11 | BioLegend | 100353 |

| Anti-CD45 | FITC | 30-F11 | BioLegend | 103108 |

| Anti-CD8 | PE-Cy7 | 53-6.7 | BioLegend | 100722 |

| IL-17A | APC | TC11-18H10.1 | BioLegend | 506916 |

Intrinsic Aortic Mechanical Properties

Following overnight shipment in an iced physiological solution, aortas were cleaned of perivascular tissue, and the intercostal branches were ligated using single strands from a braided 7-0 nylon suture. Vessels were then cannulated on pulled glass micropipettes, secured with proximal and distal ligatures using 6-0 silk suture, and tested mechanically using a custom computer-controlled biaxial device as previously described (22). Tests yielded cyclic pressure-diameter and axial force-length data, from which were calculated biaxial metrics such as wall stress, stiffness, and energy storage. This method analyzes properties of the aorta independent of extravascular supporting structures encountered in vivo. Previous studies over years within our laboratory have confirmed that overnight cold storage has no significant effect on measured passive geometrical or mechanical metrics, a finding that was recently confirmed independently by another group (23).

In Vivo Measure of Pulse Wave Velocity

Following anesthesia with isoflurane, mice were placed in the supine position and hair removed from their abdomen and chest with depilatory cream. Ultrasound images of the descending thoracic and abdominal aortas and Doppler measures of pulse wave velocity were obtained.

Renal Function Studies

The ability to excrete a sodium and volume load was assessed as previously described (15). Briefly, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of normal saline equal to 10% of their body weight and were immediately placed in a metabolic chamber for 4 h. The volume of urine produced in 4 h was recorded and total urine sodium determined using flame photometry. Spot urines were obtained for albumin and creatinine. Urine was stored at −80°C until assays were performed.

Assays for Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin, Albumin, and Creatinine

Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL; R&D Systems), albumin, and creatinine were quantified by ELISA as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Seven-millimeter sections of thoracic aorta were stained with Masson’s trichrome or Picrosirius red to assess vascular collagen. Immunostaining for α smooth muscle actin was used to quantify medial thickness. Adventitial and medial cross-sectional areas were quantified using planimetry. No image manipulation was performed.

Histology and Renal Tubular Injury Scoring

Tubules were scored by evaluating 10 fields per animal on periodic acid Schiff (PAS)-stained sections at ×40 magnification, as previously published (24, 25). Images were scanned and not further altered. Each field was blindly scored for dilated tubules, loss of proximal tubule brush border, cellular vacuolization, tubular degeneration, and casts. Fields were scored 0 (normal, no abnormalities observed), 1 (≤25% abnormal field), 2 (≤50% abnormal), 3 (≤75% abnormal), or 4 (100% abnormal) and were averaged to generate a tubular injury score for each animal.

Human Studies

We enrolled nine consecutive patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting in whom transesophageal echocardiograms and Doppler measures of aortic pulse wave velocity are routinely performed simultaneously with measures of intraarterial pressure. We calculated aortic compliance from images of the descending thoracic aorta as follows: (systolic diameter − diastolic diameter)/(systolic pressure − diastolic pressure). Blood samples obtained during these procedures were transferred to our laboratory and immediately subjected to flow cytometry to quantify CD1c+/Axl+/Siglec6+ cells and total phospho-Axl cells.

Statistical Analysis and Data Presentation

Data are presented as means ± SE. Normality of data distribution was ascertained using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Unpaired t tests were used to compare two normally disturbed variables. For comparison of 2 × 2 design, an aligned rank test for overall significance and interactions was used, followed by post hoc comparisons of relevant values using a Mann–Whitney test and Bonferroni corrections. Reported P values reflect the Bonferroni correction. Data were analyzed in R and GraphPad Prism. R2 values for the correlations between pulse wave velocity and aortic compliance with phospho-Axl+ cells and Axl+/Siglec6+ dendritic cells (ASDCs) were quantified using Spearman’s coefficients. Sample sizes were determined using power analyses using G*Power to ensure a power of 0.85 at a P value of 0.05.

RESULTS

Persistent Aortic Remodeling and Loss of Windkessel Function after 2 Wk of Hypertension

Systolic BP averaged 120 ± 0.9 and 119 ± 2.9 mmHg 1 wk after cessation of sham or ANG II infusion, respectively, and remained at this normal range throughout the 6-mo recovery period (Fig. 1A). Despite this normalization of BP, we observed persistent aortic remodeling, as evidenced by Masson’s trichrome blue and Picrosirius red staining (Fig. 1B). Both the vascular adventitia (Fig. 1C) and the media, identified by α-actin immunostaining (Fig. 1D), remained thickened at 2 and 4 mo in mice that received ANG II. At 6 mo, there was regression of medial thickness such that these were no longer statistically different between mice that had received ANG II or sham infusion (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Effects of a prior 2-wk episode of hypertension on aortic morphology. A: blood pressures measured at 1 wk and 2, 4, and 6 mo following a 2-wk infusion of ANG II (n = 5–8 per group). B: examples of hematoxylin and eosin, Picrosirius red, and Masson’s trichrome staining of sections from the perfusion-fixed thoracic aorta from sham and ANG II mice at 2, 4, and 6 mo following ANG II infusion. C: quantifies the adventitial area, obtained from planimetry of Masson’s trichrome images (n = 5–9). D and E: examples of smooth muscle α-actin staining and quantification of medial area from these images (n = 5–9). Table: results of overall comparisons that were performed using aligned rank transformation analysis of variance. Between-group comparisons were made with a Mann–Whitney test followed by a Bonferroni correction. P values reflect this correction.

Passive aortic mechanical properties at 0, 2, 4, and 6 mo after 2 wk of ANG II infusion are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2. When loaded at a pressure of 100 mmHg, the internal diameter was reduced in mice immediately after ANG II infusion compared with sham-infused mice but was not statistically different at the following times (Fig. 2A). Circumferential material stiffness, a value normalized to vascular volume, was always reduced following ANG II infusion compared with sham infusion (Fig. 2B). Loaded aortic wall thickness, reflecting both the medial and adventitial layers, was increased in mice that had received ANG II, and this persisted for 2, 4, and 6 mo (Fig. 2C). Importantly, stored energy, reflecting the Windkessel function, was diminished by almost 50% in the mice that had experienced 2 wk of ANG II infusion compared with sham-infused mice at all times examined (Fig. 2D). In sham-infused animals, there was also a modest age-dependent decrease in stored energy at 6 mo.

Figure 2.

Short- and long-term effects of a 2-wk episode of hypertension on aortic mechanics. Mice underwent a 2-wk infusion of ANG II as in Fig. 1, and aortas were studied as previously described. Comparisons are shown for immediately after and 2, 4, and 6 mo following a 2-wk infusion of either vehicle (sham) or ANG II for aortic loaded internal diameter (A), circumferential stiffness (B), loaded thickness (C), and stored energy (D). Values are n = 5 for each group, and overall comparisons were performed using two-way ANOVA. When significance was indicated, a Sidak’s multiple comparison was performed to detect differences between groups.

Table 2.

Passive aortic mechanics immediately after 2, 4, and 6 mo post-ANG II

| Descending Thoracic Aorta-Fixed Pressure |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 Ctrl (8 mo old) | 0 mo |

2 mo |

4 mo |

6 mo |

|||||

| Post-sham | Post-ANG II | Post-sham | Post-ANG II | Post-sham | Post-ANG II | Post-sham | Post-ANG II | ||

| N | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Unloaded dimensions | |||||||||

| Wall thickness, μm | 107 ± 3.9 | 112 ± 2.7 | 191 ± 4.6 | 110 ± 4.8 | 149 ± 12.8 | 117 ± 5.7 | 159 ± 7.4 | 124 ± 2.6 | 158 ± 10.4 |

| Outer diameter, μm | 956 ± 21 | 888 ± 9 | 1,142 ± 34 | 928 ± 15 | 1,089 ± 41 | 924 ± 19 | 1,006 ± 27 | 972 ± 17 | 1,031 ± 28 |

| Axial length, mm | 4.56 ± 0.25 | 4.93 ± 0.16 | 5.28 ± 0.22 | 5.78 ± 0.45 | 5.60 ± 0.34 | 5.21 ± 0.53 | 5.64 ± 0.45 | 6.64 ± 0.28 | 6.32 ± 0.48 |

| Loaded dimensions (pressure = 100) | |||||||||

| Outer diameter, μm | 1,422 ± 21.3 | 1,344 ± 11.7 | 1,358 ± 33.3 | 1,467 ± 21.2 | 1,506 ± 45.4 | 1,372 ± 28.2 | 1,386 ± 24.2 | 1,448 ± 36.2 | 1,405 ± 40.5 |

| Wall thickness, μm | 44 ± 1.9 | 41 ± 0.6 | 108 ± 6.9 | 41 ± 2.2 | 69 ± 7.2 | 44 ± 2.0 | 72 ± 4.8 | 51 ± 1.0 | 76 ± 5.4 |

| Inner radius, µm | 667 ± 10.9 | 631 ± 6.2 | 570 ± 18.4 | 692 ± 8.9 | 684 ± 24.3 | 642 ± 12.9 | 621 ± 11.4 | 673 ± 17.5 | 627 ± 21.5 |

| In vivo axial stretch (−) | 1.49 ± 0.01 | 1.64 ± 0.01 | 1.35 ± 0.02 | 1.53 ± 0.02 | 1.42 ± 0.01 | 1.61 ± 0.02 | 1.43 ± 0.03 | 1.48 ± 0.02 | 1.37 ± 0.02 |

| In vivo circumferential stretch (−) | 1.62 ± 0.02 | 1.68 ± 0.02 | 1.32 ± 0.04 | 1.74 ± 0.03 | 1.53 ± 0.05 | 1.65 ± 0.01 | 1.55 ± 0.02 | 1.65 ± 0.02 | 1.52 ± 0.03 |

| Systolic Cauchy stresses, kPa | |||||||||

| Circumferential | 202 ± 9.4 | 207 ± 4.4 | 72 ± 5.7 | 227 ± 10.2 | 140 ± 20.4 | 194 ± 7.3 | 117 ± 7.7 | 177 ± 3.8 | 113 ± 9.7 |

| Axial | 165 ± 8.2 | 223 ± 7.0 | 66 ± 7.1 | 201 ± 13.9 | 119 ± 16.8 | 184 ± 9.3 | 109 ± 10.3 | 156 ± 5.2 | 97 ± 9.7 |

| Systolic linearized stiffness, MPa | |||||||||

| Circumferential | 1.33 ± 0.01 | 1.28 ± 0.07 | 0.67 ± 0.03 | 1.45 ± 0.04 | 0.98 ± 0.28 | 1.30 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 1.36 ± 0.12 | 1.14 ± 0.18 |

| Axial | 1.29 ± 0.06 | 2.21 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 2.01 ± 0.08 | 1.34 ± 0.21 | 1.84 ± 0.20 | 1.26 ± 0.11 | 1.89 ± 0.14 | 1.25 ± 0.15 |

| Systolic stored energy, kPa | 48 ± 3.0 | 57 ± 2.0 | 12 ± 1.9 | 59 ± 4.3 | 31 ± 4.8 | 52 ± 2.5 | 26 ± 2.6 | 42 ± 1.2 | 23 ± 2.4 |

| Distensibility, 1/MPa | 20 ± 1.3 | 21.30 ± 1.01 | 13.41 ± 1.75 | 17.53 ± 1.09 | 15.98 ± 1.06 | 19.45 ± 1.81 | 17.70 ± 1.39 | 13.68 ± 0.75 | 10.77 ± 1.35 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of mice/group.

Brief Hypertension Induces Long-Term Changes in Aortic Gene Expression

In keeping with sustained histomechanical effects of a brief episode of hypertension, we observed marked changes in the aortic transcriptome 2 and 4 mo after exposure to sham versus ANG II infusion (Fig. 3). For this analysis, we eliminated rare transcripts (<10 copies) and used a false discovery rate of 0.010 (gray line in Fig. 3, A–C). We observed 469 genes that were significantly different in aortas of mice that received ANG II versus sham infusion 2 mo earlier, with the majority being downregulated (Fig. 3, A and D). A similar comparison identified 535 genes that were differentially expressed between mice 4 mo after either ANG II or sham infusion (Fig. 3, B and D). By 6 mo, differences in gene expression between these groups were minimal (Fig. 3, C and D). There was almost no overlap of gene expression profiles at 2 and 4 mo and no genes were consistently changed at all time points (Fig. 3D). The most upregulated gene at 2 mo was early growth response (Egr) 3, a transcriptional regulator that has been implicated in T-cell differentiation and polarization (26). Apold1 was also markedly upregulated 2 mo following ANG II infusion. Apold1, also known as the vascular early response gene or VERGE, has been implicated as an early response gene to endothelial stress, and it modulates endothelial permeability (27). Several genes that encode skeletal muscle contractile proteins, including myosin heavy chains 1 and 2, were upregulated at this time (Fig. 3E). The most downregulated gene at 2 mo was Wif1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling (Fig. 3, A and D). At 4 mo, the most upregulated gene was complement factor H-related protein 2 (Fig. 3E), which inhibits the alternate pathway of complement activation (28). The most significantly increased genes included the macrophage marker CD68, C-C motif ligand 8 (CCl8), also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein-2, and membrane spanning 4a7 (Ms4a7), a member of the MSA4 tetraspanin family expressed on macrophages (29).

Figure 3.

Transcriptomic changes in aortic gene expression following a 2-wk episode of hypertension. Values are from RNA sequencing from aortas of four mice in each group. A–C: volcano plots of significantly up- and downregulated genes. Gray line delineates false discovery rate of 0.10. D: Venn diagram summarizing the number of genes that were significantly different between sham- and ANG II-infused mice at ×3. E: heat maps of the top 20 up- and downregulated genes at 2 and 4 mo.

Progressive Renal Injury after Hypertension

In population studies, aortic stiffening appears to predispose to renal dysfunction and albuminuria (11, 30), and renal dysfunction can further promote hypertension and renal damage in a feed-forward fashion. We, therefore, examined parameters of renal function in mice following the 2-wk episode of hypertension. Mice that had received a sham infusion 2 mo earlier excreted 88 ± 7% of an acute volume load in the ensuing 4 h. This response was similar 4 and 6 mo after a sham infusion. In contrast, mice that had been exposed to ANG II at 2, 4, and 6 mo earlier excreted 51 ± 9%, 48 ± 9%, and 63 ± 10% of this volume challenge, respectively (Fig. 4A). Two-way ANOVA indicated that the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio increased in the months following ANG II infusion compared with sham infusion (Fig. 4B). Likewise, periodic acid Schiff staining, indicative of tubular injury, was also increased in the months following ANG II infusion (Fig. 4, C–E).

Figure 4.

Persistent effects of hypertension on renal function. A: response to a volume challenge. Mice were injected with normal saline (ip) and immediately placed in a metabolic chamber for 4 h with urine output measured. B: urinary albumin/creatinine levels determined using ELISAs. C and D: representative periodic acid Schiff (PAS) stains for renal tubular injury. E: mean values for PAS scores at 2, 4, and 6 mo. Table: results of the aligned rank transformation ANOVA for these parameters. When between-group significance was indicated, a post hoc Mann–Whitney test followed by a Bonferroni correction was performed (n = 6–8).

Effect of Axl Inhibition on Parameters of Aortic Remodeling, Mechanical Properties, and In Vivo Pulse Wave Velocity following Hypertension

The aforementioned studies indicated that a 2-wk period of hypertension causes sustained aortic remodeling and renal dysfunction. We previously reported that GAS6/Axl signaling plays a critical role in immune activation in hypertension and that mechanical stretch stimulates release of GAS6 from the endothelium (12). Given that aortic stiffening can increase the propagation of pulse waves into the microcirculation, we investigated the effect of Axl blockade in modulating renal and aortic inflammation after ANG II-induced hypertension. Again, mice received either 2 wk of ANG II or vehicle infusion by osmotic minipump. Mice were then randomized to receive the Axl inhibitor R428 (25 mg/kg) in the drinking water beginning 2 mo after cessation of ANG II. Given that the aortic morphology and mechanics and parameters of renal dysfunction were relatively stable from 4 to 6 mo, we focused these studies on the 4-mo timepoint. As in the studies presented in Fig. 1A, blood pressure was normal 1 wk after cessation of ANG II infusion, and we found no difference in blood pressure in mice that received R428 versus those that did not at 4 mo following the infusion (Fig. 5A). Examples of Elastica van Gieson’s stains and birefringent images of Picrosirius red stains of aortas are shown in Fig. 5B and quantified in Fig. 5, C–F. We observed an increase in total areas of collagen and elastin in mice that received ANG II without R428 treatment but not in those that received R428 (Fig. 5, C and D). When expressed as a percent volume change, elastin was not significantly changed by either ANG II or R428 treatment, nor did we observe a difference in the adventitial to medial collagen ratio (Fig. 5, E and F). No major changes in the percentage of either thick or thin aortic collagen were apparent using birefringence imaging (data not shown). Biaxial mechanical testing showed that R428 treatment caused a decrease in aortic internal diameter independent of ANG II exposure (Fig. 5G) and prevented the increase in loaded aortic wall thickness caused by ANG II (Fig. 5H). As shown in Fig. 2D, we observed a decrease in material stiffness in aortas of mice that had received ANG II infusion (Fig. 5I). Interestingly, R428 treatment reduced aortic energy storage in mice that had not received ANG II infusion but had no statistically significant effect on aortic stored energy in mice that had received ANG II infusion (Fig. 5F). Statistical analysis of the R428 treatment on aortic mechanics is shown in Table 3. These measures of aortic mechanics ex vivo might not reflect in vivo aortic properties, which are influenced by extravascular structures, including perivascular fibrotic material. To assess aortic stiffness in vivo, we measured pulse wave velocity in another subset of mice. Similar to prior reports (31), in sham-treated mice, aortic pulse wave velocity averaged 326 ± 3 cm/s (Fig. 5K). This was increased by almost 50% in mice that had received ANG II infusion 4 mo earlier. Notably, R428 treatment increased pulse wave velocity in sham-treated mice and had no effect in mice that had received ANG II infusion. Taken together, these findings confirm the data presented in Fig. 2 showing that prior ANG II treatment has dramatic and persistent effects on aortic remodeling and that these changes, likely together with extravascular alterations, increase pulse wave velocity in vivo. Blockade of Axl only moderately alters ex vivo mechanical properties and paradoxically increases aortic pulse wave velocity in animals that did not receive ANG II infusion.

Figure 5.

Effect of Axl blockade on blood pressure and aortic mechanics. Mice underwent a 2-wk infusion of ANG II; then, 2 mo after cessation of this infusion, R428 was added to the drinking water or not for the ensuing 2 mo. A: systolic blood pressure estimated by tail-cuff measures (n = 5). B: examples of Elastica van Gieson’s stains (top) and birefringent images of Picrosirius stains of aortas. C–F: quantification of elastin and collagen areas (n = 5). Values were compared using an unpaired t test. G–J: parameters of aortic mechanics in sham- and ANG II-treated mice with and without R428 treatment (n = 5 for each). K: pulse wave velocity (PWV) measured by Doppler ultrasound in anesthetized mice (n = 2 or 3 for each). Table: results of overall comparisons that were performed using aligned rank transformation analysis of variance. Between-group comparisons were made with a Mann–Whitney test followed by a Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

Effect of R428 on passive mechanics 4 months after ANG II

| Descending Thoracic Aorta-Fixed Pressure (4 mo) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-sham | Post-sham + R428 | Post-ANG II | Post-ANG II + R428 | |

| N | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Unloaded dimensions | ||||

| Wall thickness, μm | 117 ± 5.7 | 110 ± 1.8 | 159 ± 7.4 | 123 ± 4.4 |

| Outer diameter, μm | 924 ± 19 | 834 ± 49 | 1,006 ± 27 | 876 ± 57 |

| Axial length, mm | 5.21 ± 0.53 | 4.74 ± 0.31 | 5.64 ± 0.45 | 5.31 ± 0.49 |

| Loaded dimensions (pressure = 100) | ||||

| Outer diameter, μm | 1,372 ± 28.2 | 1,183 ± 69.7 | 1,386 ± 24.2 | 1,236 ± 77.4 |

| Wall thickness, μm | 44 ± 2.0 | 48 ± 1.8 | 72 ± 4.8 | 54 ± 3.5 |

| Inner radius, µm | 642 ± 12.9 | 543 ± 34.8 | 621 ± 11.4 | 564 ± 38.0 |

| In vivo axial stretch (−) | 1.61 ± 0.02 | 1.46 ± 0.01 | 1.43 ± 0.03 | 1.46 ± 0.03 |

| In vivo circumferential stretch (−) | 1.65 ± 0.01 | 1.57 ± 0.03 | 1.55 ± 0.02 | 1.57 ± 0.03 |

| Systolic Cauchy stresses, kPa | ||||

| Circumferential | 194 ± 7.3 | 151 ± 10.9 | 117 ± 7.7 | 141 ± 11.7 |

| Axial | 184 ± 9.3 | 165 ± 7.4 | 109 ± 10.3 | 147 ± 13.0 |

| Systolic linearized stiffness, MPa | ||||

| Circumferential | 1.30 ± 0.07 | 1.18 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 1.06 ± 0.09 |

| Axial | 1.84 ± 0.20 | 2.00 ± 0.17 | 1.26 ± 0.11 | 1.89 ± 0.29 |

| Systolic stored energy, kPa | 52 ± 2.5 | 37 ± 2.6 | 26 ± 2.6 | 34 ± 3.9 |

| Distensibility, 1/MPa | 19.45 ± 1.81 | 15.76 ± 1.42 | 17.70 ± 1.39 | 16.50 ± 1.15 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of mice/group.

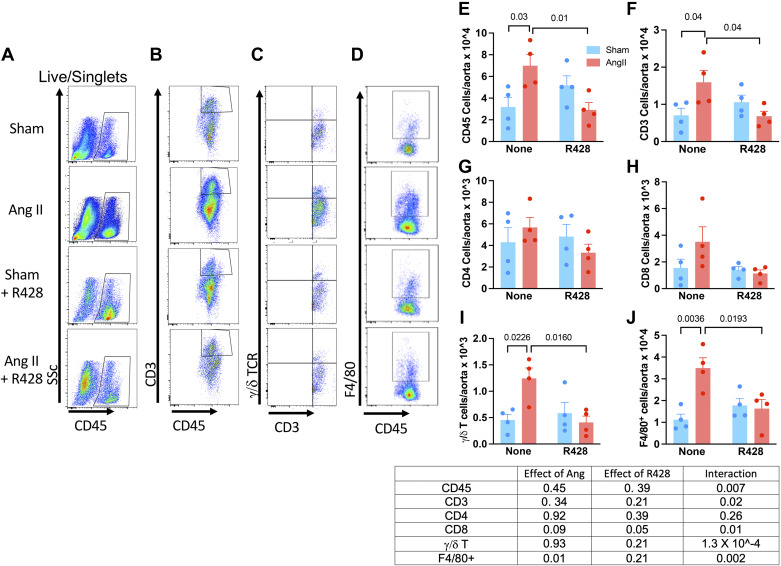

Axl Inhibition Reduces Aortic Inflammation after 2 Wk of Hypertension

Flow cytometry was used to quantify total aortic leukocytes (CD45+), T lymphocytes (CD3+), monocyte/macrophages (F4/80+), and γδ T cells 4 mo after cessation of ANG II infusion (Fig. 6). We observed persistent increases in total aortic leukocytes (Fig. 6, A and D), T cells (CD3+ cells, Fig. 6, B and E), and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6F). Treatment with R428 normalized each of these cell types in the aorta. Among live singlets, there were few CD4+ cells present in the aortas at this time, and these were not different between the sham- and ANG II-treated animals and were not changed by R428 treatment (Fig. 6G). Notably, there was substantial accumulation of γ/δ T cells in aortas of mice that had experienced prior hypertension, and this was likewise normalized by R428 administration (Fig. 6, C and H). Intracellular staining revealed a significant increase in IFNγ-producing CD8+ and γ/δ T lymphocytes, which was completely prevented with Axl inhibition (Fig. 7, A and B). Likewise, IL-17A+ γ/δ T cells were markedly increased in mice with prior hypertension, and this was likewise normalized by R428 (Fig. 7E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that GAS6/Axl signaling contributes to the accumulation of aortic immune cells and their production of inflammatory cytokines in the months following a brief episode of hypertension.

Figure 6.

Aortic-infiltrating cells 4 mo after a 2-wk episode of hypertension and effect of Axl blockade. Single-cell suspensions from aortic homogenates were subjected to flow cytometry. A–D: example flow plots. Mean data ± SE are compared between mice that had received ANG II vs. sham infusions with or without Axl blockade with R428 for total leukocytes (CD45; E), T cells (CD3; F), CD4+ T cells (G), CD8+ T cells (H), γ/δ T cells (I), and F4/80+ cells (J). Table: results of aligned rank transformation and subsequent two-way ANOVA. Data are n = 4 for all.

Figure 7.

Intracellular staining for IFNγ and IL-17A in subsets of aortic-infiltrating T cells. Mean data ± SE for aortic cells from mice that had received either sham or ANG II infusion with and without treatment with the Axl inhibitor R428 for IFNg in CD4+, CD8+, and γ/δ T cells (A, C, and D) and IL-17A in CD4+ and γ/δ T cells (B and E). Data represent further analysis of samples from Fig. 6 and were analyzed with aligned rank transformed ANOVA and a Mann–Whitney post hoc test with Bonferroni correction. Data are n = 4 for all.

Renal Inflammation Persists following an Episode of Hypertension but Is Ameliorated by Blockade of GAS6/Axl Signaling

We also used flow cytometry to estimate the presence of immune cells in the kidneys of mice 4 mo after the 2-wk infusion of ANG II. The gating strategy for these analyses was the same as that shown in Fig. 6, A–D, for aortic cells. Total leukocytes (CD45+ cells, Fig. 8A) and CD3+ T cells (Fig. 8B) were increased by the prior episode of hypertension, but these values were normalized by R428 therapy. As in the aorta, there were few CD4+ cells in the kidneys, and these were similar between groups (Fig. 8C). Although we did not detect a significant increase in CD8+ T cells in the kidneys because of prior hypertension, R428 significantly decreased these cells in both the sham- and ANG II-infused animals (Fig. 8D). In accord with our findings in the aorta, mice that had ANG II infusion 4 mo earlier exhibited a significantly greater number of renal γ/δ T cells, and strikingly, R428 reduced these cells in both the sham and ANG II groups (Fig. 8E). There was a trend for macrophages to be increased by the prior infusion of ANG II, but R428 significantly reduced these F4/80+ cells (Fig. 8F). Intracellular staining revealed that few renal γ/δ T cells produced IFNγ, and these were increased in mice that received ANG II and paradoxically further increased by R428 treatment (Fig. 8G). Among γ/δ T cells, there was a marked increase in those producing IL-17A among mice that previously received ANG II infusion, but this was also prevented by R428 treatment (Fig. 8H).

Figure 8.

Flow cytometric analysis of renal-infiltrating cells 4 mo after a 2-wk episode of hypertension and effect of Axl blockade. Single-cell suspensions of renal homogenates were stained for the indicated surface markers and then fixed and permeabilized for assessment of intracellular levels of IFNγ and IL-17A. Mean data ± SE are compared between mice that had received ANG II vs. sham infusions with or without Axl blockade with R428 for total leukocytes (CD45; A), T cells (CD3; B), CD4+ T cells (C), CD8+ T cells (D), γ/δ T cells (E), F4/80+ cells (F), IFNg+ γ/δ T cells (G), and IL-17A+ γ/δ T cells (H). Table: results of aligned rank transformation ANOVA. Data are n = 5 or 6 for all.

Immune Cells Doublets Are Present in the Aorta and Kidney following an Episode of Hypertension and Are Reduced by Axl Blockade

In the process of analyzing our flow cytometric analysis, we discovered that a slight adjustment of the forward scatter area versus forward scatter height gates revealed events that were positive for CD4, CD8, and F4/80 (Fig. 9A). Although such cell conjugates have traditionally been considered technical artifacts, recent studies have suggested that these may reflect biologically relevant cell/cell interactions, in particular immune synapse formation between antigen-presenting cells and T cells (32, 33). We therefore quantified the presence of these complexes and found a trend for F4/80/CD3 doublets (Fig. 9B) to be increased in the aortas of mice that had previously received ANG II infusion and for this to be abrogated in mice treated with R428. A similar trend was noted for complexes of F4/80 and CD4+ cells. Most notably, F4/80/CD8+ T-cell complexes and CD4/CD8+ T-cell complexes were increased in mice with prior hypertension and were prevented by R428 treatment (Fig. 9B and embedded in Fig. 9, table). Fewer complexes were observed in the kidney, and these were not affected by prior ANG II treatment or R428 (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

Evidence on myeloid/T-cell interaction in aortas and kidneys of mice 4 mo after ANG II-induced hypertension and effect of R428. A: adjusted forward scatter/side scatter gating. B: presence of clusters of F4/80+ cells with all T cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+/CD8+-clustered cells. C: a similar analysis for renal cells. Table: results of aligned rank transformation two-way ANOVA. Data are n = 5 or 6 for all.

Renal Injury and Dysfunction Persist after an Episode of Hypertension and Are Improved by Axl Blockade

In keeping with a functional consequence of persistent renal inflammation encountered in this model of aortic stiffening, we found that urinary NGAL was markedly increased 4 mo after ANG II infusion and was normalized by R428 treatment (Fig. 10A). We also analyzed the diuretic response to a volume challenge caused by an intraperitoneal injection of normal saline equivalent to 10% of body weight and found that this was diminished in mice that had received ANG II infusion 4 mo earlier; this too was prevented by R428 administration (Fig. 10B). Tubular injury, as reflected by PAS scoring, was increased in mice that had received ANG II infusion 4 mo earlier and was normalized by R428 treatment. Taken together, these data suggest that inhibiting Axl signaling reduces renal dysfunction and damage after ANG II-induced hypertension.

Figure 10.

Prolonged evidence of renal injury and dysfunction following an episode of hypertension and improvement with Axl blockade. A: urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels measured by enzyme-linked immunoassays. B: urine excretion of a volume challenge. C and D: example of tubular injury and the tubular injury score as assessed by periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining. Table: results of overall comparisons that were performed using aligned rank transformation ANOVA. Between-group comparisons were made with a Mann–Whitney test followed by a Bonferroni correction. P values reflect this correction.

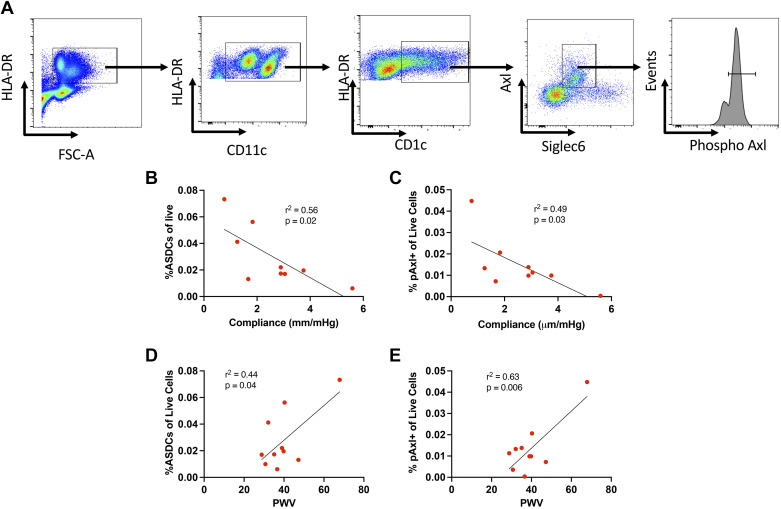

Relationship between Aortic Compliance, Pulse Wave Velocity, and Axl Activation in Humans

Demographics of humans studied are shown in Table 4. All were undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, and the majority were Caucasian, were male, and had hypertension; however, at the time of the study, their mean arterial pressure was normal. The gating strategy used to detect circulating ASDCs (CD1c+/Axl+/Siglec6+) is shown in Fig. 11A. Circulating AS cells, as a percentage of CD45 cells, were inversely proportional to aortic compliance and directly proportional to pulse wave velocity (Fig. 11, C and D). Likewise, the percentage of CD45 cells that were phospho-Axl+ correlated inversely with aortic compliance and directly with pulse wave velocity (Fig. 11, E and F). These data support the concept that aortic stiffness affects Axl activation in humans.

Table 4.

Demographics of humans studied

| Characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| Subjects, n | 9 |

| Age, yr | 70 [62, 71] |

| Female | 1 (11) |

| Height, cm | 178 [170, 180] |

| Weight, kg | 81.6 [74.4, 90.5] |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25 [23, 31] |

| African-American ancestry | 2 (22) |

| Medical history | |

| Congestive heart failure | 3 (33) |

| Hypertension | 8 (89) |

| Current smoking | 2 (22) |

| Diabetes | 5 (56) |

| Hemodynamic data | |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 61 [51, 68] |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 83 [73, 91] |

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2 | 1.9 [1.6, 2.2] |

Binary characteristics are reported as n (%) and continuous characteristics as medians [25th percentile, 75th percentile].

Figure 11.

Relationship of aortic compliance and pulse wave velocity (PWV) to Axl+/Siglec6+ dendritic cells (ASDCs) and phospho-Axl (pAxl)+ cells. Transesophageal echocardiograms and measures of PWV were obtained in nine patients during cardiac surgery. Simultaneously collected blood samples were analyzed for circulating ASDCs and pAxl+ cells. A: gating strategy for live/singlet cells. B and C: relationships of ASDCs and %pAxl+ live cells to aortic compliance. D and E: relationships of ASDCs and %pAxl+ live cells to PWV.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we characterized a model of persistent aortic remodeling following a brief episode of hypertension and showed that it recapitulates features of human aortic remodeling observed in aging, hypertension, and obesity. Mice exposed to 2 wk of hypertension caused by ANG II infusion developed persistent aortic remodeling characterized by collagen deposition, thickening of the aortic media and adventitia, and a striking and persistent loss of energy storage, reflecting reduced Windkessel function. These perturbations were associated with effects on the kidney, including albuminuria, elevated urinary NGAL, and a reduced capacity to excrete a volume challenge. These studies indicate a role of GAS6/Axl signaling in causing persistent inflammation and renal injury and suggest that blockade of this pathway is a therapeutic option to prevent ongoing effects of aortic remodeling on end organs.

Our ex vivo analysis of aortic mechanics and morphology confirmed persistent aortic thickening for 6 mo following a 2-wk episode of hypertension. Material stiffness, which reflects distensibility normalized to wall thickness, was significantly reduced at the 2- and 4-mo timepoints. It is emphasized that this metric reflects intrinsic properties of the aorta after removing the supporting structures present in vivo. This reduction in intrinsic stiffness likely reflects incomplete and inefficient remodeling following an episode of hypertension, perhaps involving changes in the collagen III to I ratios and perhaps loss of collagen undulation or gain of cross links. A striking finding of our study was the persistent loss of stored energy, which was reduced by 80% immediately after the 2-wk infusion of ANG II and did not recover during the ensuing 6 mo. This loss of stored energy property reflects the inability of the aorta to recoil in diastole and could affect diastolic perfusion and enhance end-organ damage. In vivo, we found that pulse wave velocity measured by Doppler ultrasound was increased in mice that had received ANG II infusion 4 mo earlier, likely reflecting the perivascular fibrosis that is obvious in Figs. 1 and 5.

Consistent with these functional changes, we found an evolution of aortic gene expression profiles at 2 and 4 mo after this brief episode of hypertension. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analyses revealed several pathways that likely have local and systemic impact. Several inflammatory pathways were upregulated at 2 mo, and notably, the most downregulated pathway was that of smooth muscle contraction. This was typified by upregulation of skeletal muscle myosin heavy chains Myh1 and Myh2 and an 80% downregulation of Myh11 (light green symbol, Fig. 3A), a smooth muscle myosin. These changes possibly reflect a dedifferentiation of the smooth muscle phenotype. Notably, the NADPH oxidase catalytic subunit Nox4 was downregulated by 80% (P = 4 × 10−13) at 2 mo (blue symbol, Fig. 3A). Clempus et al. (34) showed that Nox4 is required for the maintenance of the differentiated vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype, for it modulates the expression of calponin and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain. In keeping with this, we also observed an 82% downregulation of calponin-1 (P = 8.8 × 10−9). These findings are of interest because recent work from our groups has shown that effective vasoreactivity plays an important role in controlling matrix turnover by vascular cells and that loss of smooth muscle contractile capacity can lead to maladaptive remodeling (35). The most downregulated gene at 2 mo was Wif1 (dark green symbol, Fig. 3A), a negative regulator of Wingless-type (WNT) signaling, which in turn modulates tissue growth factor-β signaling and fibrosis (36). The most upregulated gene at 4 mo was complement factor H-related protein 2 (Cfhr2). Its role in aortic remodeling remains undefined, but Eberhardt et al. (28) showed that it inhibits complement 3 (C3) convertase and, ultimately, the alternative complement pathway. Three of the most significantly changed genes include Cd68, Ms4A7, and Ccl8, which might reflect or influence myeloid infiltration, as noted in our flow cytometric analysis of the aortas at 4 mo. Notably by 6 mo, changes in gene expression had essentially resolved. Although the precise roles of these transcriptional changes remain to be defined, the evolutionary profile of gene expression after a period of hypertension is congruent with a prolonged process of remodeling.

An important conclusion of the present studies is that the GAS6/Axl pathway seems to mediate a portion of the aortic and renal inflammation following ANG II infusion. Inhibition of this pathway by administration of R428 markedly reduced infiltration of immune cells in both the kidney and the aorta, normalized the ability of the kidney to eliminate a volume challenge, and normalized urinary NGAL levels, a marker of renal interstitial injury. We have recently shown that activated endothelial cells release increased amounts of GAS6, which in turn can modulate the phenotype of adjacent monocytes toward an activated, dendritic cell-like phenotype (12). In this prior study, we showed that Axl and GAS6 levels in freshly harvested human endothelial cells correlated with other markers of endothelial activation, including nitrotyrosine levels, intracellular adhesion molecule-1 expression, and the accumulation of isolevuglandin protein adducts, a consequence of oxidative injury. The precise mechanisms by which Axl signaling is enhanced in the months following a period of hypertension remain undefined but could relate to persistent endothelial activation, perhaps because of altered hemodynamics.

We have previously shown that oxidative injury contributes to aortic stiffening (37) and that GAS6 stimulation of human monocytes to form Axl+/Siglec6+ (AS) dendritic cells is prevented by scavenging hydrogen peroxide with PEG catalase (12). Likewise, we found that AS cells accumulate the highest amount of isolevuglandins, a peroxidation product of arachidonic acid. Thus, another mechanism by which oxidative signaling can contribute to the long-term consequence of hypertension involves GAS6/Axl signaling.

In the present study, we found that circulating ASDCs and the presence of phospho-Axl+ cells correlate with parameters of aortic stiffening in humans. We have previously shown that human endothelial cells activated by 10% cyclical stretch release GAS6, which in turn activates human monocytes to form ASDCs, as characterized by the acquisition of CD1 and Siglec6 and increased surface expression of Axl (12). These events can be blocked by addition of R428 and by inhibition of GAS6 release using siRNA treatment of endothelial cells. Likewise, exposure of human monocytes to GAS6 promotes formation of ASDCs, as characterized by these markers and dendrite formation. In response to GAS6, phosphorylation of Axl is increased in monocytes. Thus, our measures of levels of circulating ASDCs and the levels of phospho-Axl+ cells in humans likely indicate that aortic stiffening and the resultant increases in pulse wave velocity affect long-term GAS6/Axl signaling in vivo.

A striking finding in the current study was the accumulation of γ/δ T cells in the kidneys and aorta 4 mo after the brief episode of hypertension. More than 96% of circulating T cells possess α/β T-cell receptors and the remaining 2% to 4% are γ/δ T cells. These cells arise early in development and populate peripheral tissue in waves (38). Of note, Caillon et al. (39) showed that mice lacking γ/δ T cells are protected against ANG II-induced hypertension. Interestingly, γ/δ T cells display a complex response to butyrophilin-like and butyrophilin type I transmembrane proteins and other stimulants, including phosphoproteins (40). Butyrophilins share homology to B7 ligands, which are critically important in the activation of α/β T cells, and are essential for development of experimental hypertension (41). γ/δ T cells can produce both IL-17A and IFNγ, which both contribute to hypertension (17, 19). Notably, we previously described a role of IL-17A in enhancing collagen formation by aortic fibroblasts and in mediating aortic stiffening (42). Although we found few of these cells in the aorta, there were as many γ/δ T cells as α/β CD8+ T cells in the kidney. In both the aorta and the kidney, γ/δ T cells were significantly increased by the prior ANG II exposure and were reduced by R428 treatment. Their role in mediating renal and vascular dysfunction and damage remains unclear and understanding how GAS6/Axl signaling affects their activation and function and what is the role of butyrophillins in long-term response to hypertension merits future study.

Another interesting finding in the current study was the prevalence of T-cell and myeloid doublets that were apparent on a slight shift of gating for single cells in flow cytometry. Such complexes have traditionally been thought to represent technical artifacts, but recent studies have suggested that they likely reflect immune activation in vivo (32) and can be formed in vitro upon stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) or 6-kDa early secreted antigenic target (ESAT 6) peptides (33). Habtamu et al. recently showed that the formation of these complexes was increased in samples from patients with active TB and that NFκB is translocated to the nucleus of T cells involved in such complexes. Using imaging flow cytometry, Burel et al. (32) showed that these complexes involve colocalization of LFA1 and ICAM1 at the interface of these cells, indicative of immune synapse formation. Our studies included aortic and renal homogenates and revealed complexes of cells expressing F4/80 and both CD4 and CD8 in the flow cytometry events. Unlike Burel et al. and Habtamu et al., we observed colocalization with F4/80, a marker of differentiated myeloid cells, rather than monocytes with T cells in these tissues. This likely reflects the propensity for monocytes to convert to macrophages and DCs upon transmigration into tissue. The presence of CD4 and CD8 doublets is also of interest. CD4+ cells express class I MHC and thus could present antigen to CD8+ T cells. It is also possible that these T-cell subsets simultaneously interact with antigen-presenting (F4/80+) cells. A very recent study has shown that killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs)+/CD8 T cells can interact with and suppress pathogenic CD4+ T cells in humans with autoimmune diseases and COVID19 (43). Thus, although the finding of cell conjugates might reflect technical artifacts, it may also reflect active immune synapse formation, suggesting ongoing immune activation for months after an episode of hypertension. The fact that these were increased in the aorta suggests that it might be a site for persistent immune activation following an episode of hypertension. Future studies with imaging flow cytometry, analysis of potential synapses between these cells, and how these are affected by Axl blockade will be of interest.

An interesting finding in our studies is that in sham-infused animals, R428 therapy paradoxically reduced stored energy. Although statistically not significant, in mice not treated with ANG II, there was also a trend for R428 to increase CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, and γ/δ T cells in the aorta; to increase the number of these cells producing IFNγ and IL-17A; and to increase pulse wave velocity. In accord with this, both anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory roles of GAS6/Axl signaling have been described. In autoimmune diseases, this pathway is thought to dampen inflammation (44) and is being studied for treatment of cancer (45). In contrast, we have shown that GAS6 acting on Axl can activate IL-1β formation in DCs and promotes experimental hypertension. R428 treatment and genetic deletion of Axl in either somatic or bone-marrow-derived cells blunted hypertension in response to ANG II. Likewise, GAS6 levels are elevated in humans with sepsis (46), chronic renal failure (47), and obesity (48). It is interesting to speculate that the cardiovascular effects of Axl/GAS6 signaling depend on the background level of inflammation, such that in the setting of low inflammation, this pathway enhances immune activation, whereas in the setting of high inflammation, it is inhibitory.

There are important limitations and caveats of our current study. The numbers of infiltrating T cells and macrophages we observed in the aorta and kidney are in keeping with prior reports (14, 19, 49); however, as we have discussed previously (19), the process of preparing single-cell suspensions for flow cytometry leads to unavoidable loss of cells, such that estimates likely reflect trends in numbers of cells rather than absolute numbers. To avoid further loss of cells, we did not use an activating step to estimate the numbers of cells producing IFNγ and IL-17A, and it is likely that the percentage of cells we detected capable of producing these cytokines would have been increased if these cells were stimulated by phorbol ester and calcium ionophore. The number of doublets we observed (Fig. 9) is admittedly low, but if these indeed reflect immune cell interactions, these are transient events, and our data likely reflect snapshots in time that are repeatedly occurring in vivo. The finding that these doublets are 10-fold higher in the aorta than in the kidney suggests that the aorta might serve as a site of persistent immune activation following even a brief period of hypertension.

Our current findings have potential clinical significance. As an example, women with hypertension during pregnancy have a lifelong increased risk of cardiovascular events (50, 51) and have increased pulse wave velocity, compatible with aortic stiffening (52). There is also evidence that blood pressure variability between clinic visits worsens end-organ damage (53). It is conceivable that such swings in blood pressure permanently impair the mechanical properties of large central arteries, leading to inflammatory responses in target organs like the kidney. In such conditions, targeting the Axl/GAS6 pathway might have therapeutic potential. It is also possible that strategies to target γ/δ T cells might prove effective in preventing the long-term effects of an episode of hypertension. Findings such as these underscore the concept that even after control of hypertension, there is ongoing, persistent risk that requires surveillance and that therapies for this are needed.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R35HL140016 and P01HL129941 (to D. G. Harrison), R01HL155105 (to J. D. Humphrey), R35GM145375 (to F. L. Billings), K23GM129662 (to M. G. Lopez), and R01HL105297; Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award K08 HL153789-01 (to D. M. Patrick); Ruth L. Kirschstein NIH Grant F32HL132937 (to J. P. Van Beusecum); American Heart Association Grant 17SDG33670829 (to L. Xiao); and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) BLRD Career Development Awards IK2BX005376 (to D. M. Patrick) and 1IK2BX005605 (to J. P. Van Beusecum).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.C., J.P.V.B, J.D.H., and D.G.H. conceived and designed research; W.C., J.P.V.B., L.X., D.M.P., M.A., M.G.L., F.T.B., C.C. A.W.C., and J.D.H. performed experiments; W.C., J.P.V.B., L.X., D.M.P., M.A., S.Z., M.G.L., F.T.B., C.C. A.W.C., J.D.H., and D.G.H. analyzed data; W.C., J.P.V.B., L.X., D.M.P., S.Z., M.G.L., F.T.B., C.C., A.W.C., J.D.H., and D.G.H. interpreted results of experiments; W.C., L.X., D.M.P., C.C., J.D.H., and D.G.H. prepared figures; W.C. and D.G.H. drafted manuscript; W.C., J.P.V.B., L.X., D.M.P., M.A., S.Z., M.G.L., F.T.B., C.C., A.W.C., J.D.H., and D.G.H. edited and revised manuscript; W.C., J.P.V.B., L.X., D.M.P., M.A., S.Z., M.G.L., F.T.B., C.C., A.W.C., J.D.H., and D.G.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Bart Spronck for technical advice. The Vanderbilt Translational Pathology Shared Resource prepared histological sections for analysis. Online graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com and published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adji A, O'Rourke MF, Namasivayam M. Arterial stiffness, its assessment, prognostic value, and implications for treatment. Am J Hypertens 24: 5–17, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Rourke MF, Hashimoto J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 1–13, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Safar ME. Arterial aging–hemodynamic changes and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Cardiol 7: 442–449, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell GF, Guo CY, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, Vita JA, Vasan RS, Levy D. Cross-sectional correlates of increased aortic stiffness in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 115: 2628–2636, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.667733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dietrich T, Schaefer-Graf U, Fleck E, Graf K. Aortic stiffness, impaired fasting glucose, and aging. Hypertension 55: 18–20, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Payne RA, Wilkinson IB, Webb DJ. Arterial stiffness and hypertension: emerging concepts. Hypertension 55: 9–14, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.090464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitchell GF, DeStefano AL, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Chen MH, Vasan RS, Vita JA, Levy D. Heritability and a genome-wide linkage scan for arterial stiffness, wave reflection, and mean arterial pressure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 112: 194–199, 2005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenberg AJ, Schroeder EC, Grigoriadis G, Wee SO, Bunsawat K, Heffernan KS, Fernhall B, Baynard T. Aging reduces cerebral blood flow regulation following an acute hypertensive stimulus. J Appl Physiol (1985) 128: 1186–1195, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00137.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suri S, Chiesa ST, Zsoldos E, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Griffanti L, Mahmood A, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M, Deanfield JE, Ebmeier KP. Associations between arterial stiffening and brain structure, perfusion, and cognition in the Whitehall II Imaging Sub-study: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 17: e1003467, 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woodard T, Sigurdsson S, Gotal JD, Torjesen AA, Inker LA, Aspelund T, Eiriksdottir G, Gudnason V, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Levey AS, Mitchell GF. Mediation analysis of aortic stiffness and renal microvascular function. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1181–1187, 2015. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nagarajarao HS, Musani SK, Cobb KE, Pollard JD, Cooper LL, Anugu A, Yano Y, Moore JA, Tsao CW, Dreisbach AW, Benjamin EJ, Hamburg NM, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF, Fox ER. Kidney function and aortic stiffness, pulsatility, and endothelial function in African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Kidney Med 3: 702–711.e1, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Beusecum JP, Barbaro NR, Smart CD, Patrick DM, Loperena R, Zhao S, de la Visitacion N, Ao M, Xiao L, Shibao CA, Harrison DG. Growth arrest specific-6 and Axl coordinate inflammation and hypertension. Circ Res 129: 975–991, 2021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Beusecum JP, Barbaro NR, McDowell Z, Aden LA, Xiao L, Pandey AK, Itani HA, Himmel LE, Harrison DG, Kirabo A. High salt activates CD11c+ antigen-presenting cells via SGK (serum glucocorticoid kinase) 1 to promote renal inflammation and salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 74: 555–563, 2019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 204: 2449–2460, 2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Trott DW, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Saleh MA, Itani H, Norlander AE, Wu J, Goldstein A, Arendshorst WJ, Madhur MS, Chen W, Li CI, Shyr Y, Harrison DG. Oligoclonal CD8+ T cells play a critical role in the development of hypertension. Hypertension 64: 1108–1115, 2014. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirabo A, Fontana V, de Faria AP, Loperena R, Galindo CL, Wu J, Bikineyeva AT, Dikalov S, Xiao L, Chen W, Saleh MA, Trott DW, Itani HA, Vinh A, Amarnath V, Amarnath K, Guzik TJ, Bernstein KE, Shen XZ, Shyr Y, Chen SC, Mernaugh RL, Laffer CL, Elijovich F, Davies SS, Moreno H, Madhur MS, Roberts J, Harrison DG. DC isoketal-modified proteins activate T cells and promote hypertension. J Clin Invest 124: 4642–4656, 2014. doi: 10.1172/JCI74084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 55: 500–507, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saleh MA, McMaster WG, Wu J, Norlander AE, Funt SA, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Xiao L, Chen W, Itani HA, Michell D, Huan T, Zhang Y, Takaki S, Titze J, Levy D, Harrison DG, Madhur MS. Lymphocyte adaptor protein LNK deficiency exacerbates hypertension and end-organ inflammation. J Clin Invest 125: 1189–1202, 2015. doi: 10.1172/JCI76327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Itani HA, Xiao L, Saleh MA, Wu J, Pilkinton MA, Dale BL, Barbaro NR, Foss JD, Kirabo A, Montaniel KR, Norlander AE, Chen W, Sato R, Navar LG, Mallal SA, Madhur MS, Bernstein KE, Harrison DG. CD70 exacerbates blood pressure elevation and renal damage in response to repeated hypertensive stimuli. Circ Res 118: 1233–1243, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.308111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gongora MC, Qin Z, Laude K, Kim HW, McCann L, Folz JR, Dikalov S, Fukai T, Harrison DG. Role of extracellular superoxide dismutase in hypertension. Hypertension 48: 473–481, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000235682.47673.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xiao L, do Carmo LS, Foss JD, Chen W, Harrison DG. Sympathetic enhancement of memory T-cell homing and hypertension sensitization. Circ Res 126: 708–721, 2020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bersi MR, Bellini C, Wu J, Montaniel KR, Harrison DG, Humphrey JD. Excessive adventitial remodeling leads to early aortic maladaptation in angiotensin-induced hypertension. Hypertension 67: 890–896, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van der Bruggen MM, Reesink KD, Spronck PJM, Bitsch N, Hameleers J, Megens RTA, Schalkwijk CG, Delhaas T, Spronck B. An integrated set-up for ex vivo characterisation of biaxial murine artery biomechanics under pulsatile conditions. Sci Rep 11: 2671, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheng H, Fan X, Lawson WE, Paueksakon P, Harris RC. Telomerase deficiency delays renal recovery in mice after ischemia-reperfusion injury by impairing autophagy. Kidney Int 88: 85–94, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Patrick DM, de la Visitación N, Krishnan J, Chen W, Ormseth MJ, Stein CM, Davies SS, Amarnath V, Crofford LJ, Williams JM, Zhao S, Smart CD, Dikalov S, Dikalova A, Xiao L, Van Beusecum JP, Ao M, Fogo AB, Kirabo A, Harrison DG. Isolevuglandins disrupt PU.1-mediated C1q expression and promote autoimmunity and hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus. JCI Insight 7: e136678, 2022. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.136678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miao T, Symonds ALJ, Singh R, Symonds JD, Ogbe A, Omodho B, Zhu B, Li S, Wang P. Egr2 and 3 control adaptive immune responses by temporally uncoupling expansion from T cell differentiation. J Exp Med 214: 1787–1808, 2017. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Regard JB, Scheek S, Borbiev T, Lanahan AA, Schneider A, Demetriades AM, Hiemisch H, Barnes CA, Verin AD, Worley PF. Verge: a novel vascular early response gene. J Neurosci 24: 4092–4103, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4252-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eberhardt HU, Buhlmann D, Hortschansky P, Chen Q, Böhm S, Kemper MJ, Wallich R, Hartmann A, Hallström T, Zipfel PF, Skerka C. Human factor H-related protein 2 (CFHR2) regulates complement activation. PLoS One 8: e78617, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silva-Gomes R, Mapelli SN, Boutet MA, Mattiola I, Sironi M, Grizzi F, Colombo F, Supino D, Carnevale S, Pasqualini F, Stravalaci M, Porte R, Gianatti A, Pitzalis C, Locati M, Oliveira Mj, Bottazzi B, Mantovani A. Differential expression and regulation of MS4A family members in myeloid cells in physiological and pathological conditions. J Leukoc Biol 111: 817–836, 2021. doi: 10.1002/JLB.2A0421-200R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim ED, Tanaka H, Ballew SH, Sang Y, Heiss G, Coresh J, Matsushita K. Associations between kidney disease measures and regional pulse wave velocity in a large community-based cohort: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 682–690, 2018. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hartley CJ, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Pham TT, Entman ML. Noninvasive determination of pulse-wave velocity in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H494–H500, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burel JG, Pomaznoy M, Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Weiskopf D, da Silva Antunes R, Jung Y, Babor M, Schulten V, Seumois G, Greenbaum JA, Premawansa S, Premawansa G, Wijewickrama A, Vidanagama D, Gunasena B, Tippalagama R, deSilva AD, Gilman RH, Saito M, Taplitz R, Ley K, Vijayanand P, Sette A, Peters B. Circulating T cell-monocyte complexes are markers of immune perturbations. eLife 8: e46045, 2019. doi: 10.7554/eLife.46045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Habtamu M, Abebe M, Aseffa A, Dyrhol-Riise AM, Spurkland A, Abrahamsen G. In vitro analysis of antigen induced T cell-monocyte conjugates by imaging flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods 460: 93–100, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clempus RE, Sorescu D, Dikalova AE, Pounkova L, Jo P, Sorescu GP, Schmidt HH, Lassègue B, Griendling KK. Nox4 is required for maintenance of the differentiated vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 42–48, 2007. [Erratum in Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: e8, 2007]. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251500.94478.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eberth JF, Humphrey JD. Reduced smooth muscle contractile capacity facilitates maladaptive arterial remodeling. J Biomech Eng 144: 044503, 2022. doi: 10.1115/1.4052888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Akhmetshina A, Palumbo K, Dees C, Bergmann C, Venalis P, Zerr P, Horn A, Kireva T, Beyer C, Zwerina J, Schneider H, Sadowski A, Riener MO, MacDougald OA, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH. Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF-β-mediated fibrosis. Nat Commun 3: 735, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wu J, Saleh MA, Kirabo A, Itani HA, Montaniel KR, Xiao L, Chen W, Mernaugh RL, Cai H, Bernstein KE, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, Curci JA, Barbaro NR, Moreno H, Davies SS, Roberts LJ, Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Immune activation caused by vascular oxidation promotes fibrosis and hypertension. J Clin Invest 126: 50–67, 2016. doi: 10.1172/JCI80761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ribot JC, Lopes N, Silva-Santos B. γδ T cells in tissue physiology and surveillance. Nat Rev Immunol 21: 221–232, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caillon A, Mian MOR, Fraulob-Aquino JC, Huo KG, Barhoumi T, Ouerd S, Sinnaeve PR, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. γδ T cells mediate angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Circulation 135: 2155–2162, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hayday AC, Vantourout P. The innate biologies of adaptive antigen receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 38: 487–510, 2020. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-102819-023144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vinh A, Chen W, Blinder Y, Weiss D, Taylor WR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, Harrison DG, Guzik TJ. Inhibition and genetic ablation of the B7/CD28 T-cell costimulation axis prevents experimental hypertension. Circulation 122: 2529–2537, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu J, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Trott DW, Saleh MA, Xiao L, Madhur MS, Chen W, Harrison DG. Inflammation and mechanical stretch promote aortic stiffening in hypertension through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Circ Res 114: 616–625, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li J, Zaslavsky M, Su Y, Guo J, Sikora MJ, van Unen V et al. KIR+CD8+ T cells suppress pathogenic T cells and are active in autoimmune diseases and COVID-19. Science 376: eabi9591, 2022. doi: 10.1126/science.abi9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vago JP, Amaral FA, van de Loo FAJ. Resolving inflammation by TAM receptor activation. Pharmacol Ther 227: 107893, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tanaka M, Siemann DW. Therapeutic targeting of the Gas6/Axl signaling pathway in cancer. Int J Mol Sci 22: 9953, 2021. doi: 10.3390/ijms22189953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ekman C, Linder A, Akesson P, Dahlbäck B. Plasma concentrations of Gas6 (growth arrest specific protein 6) and its soluble tyrosine kinase receptors Axl in sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndromes. Crit Care 14: R158, 2010. doi: 10.1186/cc9233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee IJ, Hilliard B, Swami A, Madara JC, Rao S, Patel T, Gaughan JP, Lee J, Gadegbeku CA, Choi ET, Cohen PL. Growth arrest-specific gene 6 (Gas6) levels are elevated in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 4166–4172, 2012. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu KS, Hung YJ, Lee CH, Hsiao FC, Hsieh PS. The involvement of GAS6 signaling in the development of obesity and associated inflammation. Int J Endocrinol 2015: 202513, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/202513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xiao L, Kirabo A, Wu J, Saleh MA, Zhu L, Wang F, Takahashi T, Loperena R, Foss JD, Mernaugh RL, Chen W, Roberts J, Osborn JW, Itani HA, Harrison DG. Renal denervation prevents immune cell activation and renal inflammation in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res 117: 547–557, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fraser A, Nelson SM, Macdonald-Wallis C, Cherry L, Butler E, Sattar N, Lawlor DA. Associations of pregnancy complications with calculated cardiovascular disease risk and cardiovascular risk factors in middle age: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Circulation 125: 1367–1380, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Skjaerven R, Wilcox AJ, Klungsøyr K, Irgens LM, Vikse BE, Vatten LJ, Lie RT. Cardiovascular mortality after pre-eclampsia in one child mothers: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ 345: e7677, 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Orabona R, Sciatti E, Sartori E, Vizzardi E, Prefumo F. The impact of preeclampsia on women's health: cardiovascular long-term implications. Obstet Gynecol Surv 75: 703–709, 2020. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parati G, Torlasco C, Pengo M, Bilo G, Ochoa JE. Blood pressure variability: its relevance for cardiovascular homeostasis and cardiovascular diseases. Hypertens Res 43: 609–620, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]