Abstract

We present a case of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in a previously immunocompetent patient. At the time of presentation, he was co-infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. This case demonstrates how infectious diseases besides human immunodeficiency virus can lead to immunosuppression for patients, placing them at risk of opportunistic infections.

Key words: co-infection, Cryptococcus, leishmaniasis, opportunistic infection

Abstract

Les auteurs présentent le cas d’une leishmaniose viscérale (LV) chez un patient auparavant immunocompétent. Au moment de consulter, il était co-infecté par un Cryptococcus neoformans. Ce cas démontre que, conjuguées au virus d’immunodéficience humaine, les maladies infectieuses peuvent provoquer une immunosuppression et rendre les patients vulnérables à des infections opportunistes.

Mots-clés : co-infection, Cryptococcus, infection opportuniste, leishmaniose

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection caused by organisms within the Leishmania genus. Different species can cause four clinical syndromes, including cutaneous, mucocutaneous, disseminated cutaneous, and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) (1). VL is caused by Leishmania donovani, seen mostly in India, East Africa, and the Middle East and Leishmania infantum, seen mostly in South and Central America, North Africa, and Europe. The former traditionally infects a wide range of individuals in terms of age and immune status while the latter has traditionally infected children and those with immunosuppression (2). However, cases in adults have been rising in the last few years (3).

Case report

A 71-year-old man with a previous history of thalassemia trait presented with 9 months of progressive fatigue and 3 months of fevers, drenching night sweats, and an 11 kg weight loss. In the past month, he had complained of a dry cough and shortness of breath.

He had previously worked in a steel factory, owned a hobby farm, and had been exposed to bat feces. He was born in Italy and had immigrated to Canada 55 years previous. His travel history included trips to Italy, most recently 3 years prior. He had not travelled to Asia, the Middle East, or Africa. He had no risk factors for HIV infection.

His examination was unremarkable with normal vital signs except for a temperature of 38.2°C. His investigations included negative urine and blood cultures and normal chest radiograph. He had pancytopenia with hemoglobin of 97 g/L (baseline 120), platelet count of 80 × 109/L and absolute neutrophil count of 1.7 × 109/L. He had positive antinuclear antibody (ANA), positive anti-dsDNA (double-stranded) antibody at 25 IU/mL, normal complement, negative rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). A bone marrow biopsy revealed 20%–25% plasma cells but was otherwise not diagnostic. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed splenomegaly of 18 cm that had a diffuse heterogeneous nature.

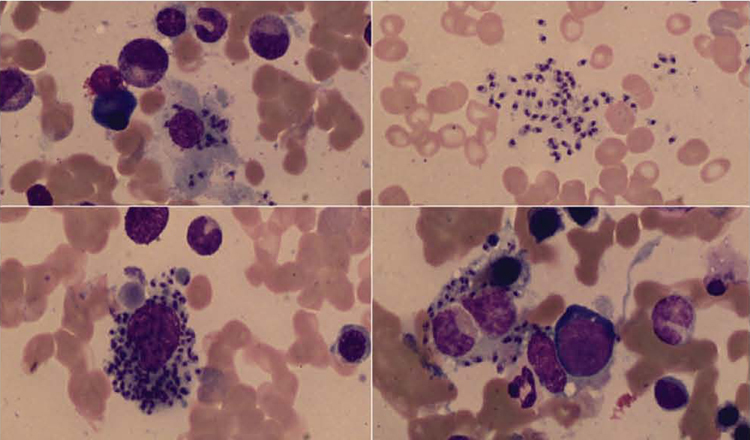

Figure 1:

On Hematoxylin and Eosin stains, the bone marrow biopsy showed increased histiocytes with cytoplasmic filling by 1.7–2.0 micron-sized organisms identified as Leishmania

Given the new oral ulcers, pancytopenia, and positive biomarkers, he met the diagnostic criteria for lupus and was started on 50 mg oral prednisone daily, with symptomatic improvement. Another bone marrow biopsy was completed to follow-up the previous findings about a week following the initiation of prednisone.

The bone marrow aspirate, using Wright’s stain showed numerous intra- and extra-cellular organisms within macrophages and monocytes. On H&E stains, the bone marrow biopsy showed increased histiocytes with cytoplasmic filling by organisms 1.7 to 2.0 microns in size. Grocott and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stains were negative.

Blood cultures were obtained, and Cryptococcus neoformans was isolated from two of eight sets using the BacT/Alert FAN aerobic bottle (bioMérieux Canada, Inc., St. Laurent, Québec). Bone marrow was sent to a reference laboratory for culture by the Isolator system (Oxoid, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Nepean, Ontario) and grew C. neoformans. Serum Cryptococcal latex agglutination (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, Ohio) was positive at a titre of 1:4 in serum and was negative in spinal fluid. The spinal fluid cell count, protein, and glucose were normal. C. neoformans was identified using routine methods, which included urease positive, germ tube negative, characteristic microscopic morphology on cornmeal, VITEK 2 yeast identification card (bioMérieux), and VITEK MS.

Blood and bone marrow cultures were negative for histoplasmosis. Molecular detection using real-time polymerase chain (PCR) for Leishmania spp was positive from the bone marrow biopsy. PCR was completed, as initial cultures did not yield histoplasmosis and, given his place of birth, he was expected to have positive serology for Leishmania. Serology was positive for L. donovani with a titre of 1:512 (positive ≥1:16). L. donovani and L. infantum are species within the L. donovani complex, and are both detected by recognized serological assays for VL. HIV serology was negative. His CD4 count was suppressed, at 100 cells/mm3 with a CD4-to-CD8 ratio of 17%.

He was treated with liposomal amphotericin B at 4 mg/kg/day for 14 days. He was subsequently stepped down to posaconazole 400 mg oral twice daily. After the result of the histoplasmosis serology was negative, he was switched to fluconazole 400 mg oral daily to complete the maintenance therapy for disseminated cryptococcosis for 8 weeks. His Leishmania results were not available until after he was already on fluconazole. His symptoms resolved by the end of therapy. His recent repeat CD4 count had increased to 470 cells/mm (ratio 20%), and his complete blood count values had returned to his baseline values.

Discussion

The case presented an HIV-negative patient with concurrent infections of VL and cryptococcosis is unusual. To our knowledge, this has not been previously described together in the literature. We hypothesize that he was infected with leishmaniasis for a prolonged period, resulting in weakened cell-mediated immunity and therefore resultant opportunistic infection. The C. neoformans was likely acute as he did not have central nervous system (CNS) involvement by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. Cryptococcus in the bloodstream is easily able to cross the blood–brain barrier and colonize brain tissue (4). We do not believe the patient ever had lupus, and we recognize that the prednisone treatment clouds the issues, especially with respect to the C. neoformans co-infection.

The bone marrow aspirate using Wright’s stain demonstrated intra- and extra-cellular organisms within reactive macrophages/monocytes. Organisms were oval, non-budding approximately 2.0 microns, with a histiocytic reaction with irregular rounded bodies on H&E stain. Fungal stains (PAS and Grocott) were negative. The differential diagnosis of intracytoplasmic organisms in bone marrow includes Leishmania, Histoplasma, Toxoplasma and Penicillium marneffei. Because of the growth of Cryptococcus from blood and bone marrow culture, Cryptococcus was also considered. The absence of staining using PAS and Grocott was consistent with leishmaniasis; however, the kinetoplast was difficult to discern. Paraffin sections may not show the kinetoplast clearly depending on the plane of sections (5). Differentiation of “yeast-like” or rounded forms can be difficult based solely on tissue pathology (6). The diagnosis of Leishmania was substantiated by PCR detection of Leishmania using the paraffin block from the bone marrow biopsy and by serology.

He was initially treated for histoplasmosis as given his recent exposure to bat guano and only remote travel to Italy it was thought the more likely diagnosis at the time of initial treatment. He had completed 4 weeks of therapy before the Leishmania results became available, and he was already much improved; therefore, we did not alter our treatment plan to reflect the Leishmania treatment recommendations better.

Leishmaniasis was probably present for several years as he had not been in an area endemic for Leishmania for at least 3 years. The typical incubation period is 2 to 6 months but has been described in the literature from weeks to years (2). Prolonged incubation periods are likely the result of years of asymptomatic infection. Asymptomatic cases are quite common, with 18 asymptomatic cases for every one symptomatic case (7). L. infantum is generally the strain of Leishmania found in Italy. Given the cross-reactivity of the serology testing, it is likely this gentleman had L. infantum. He had not had any travel to areas that predominantly have L. donovani.

Cryptococcus was likely secondary to chronic immunosuppression from leishmaniasis, with steroids playing an enhancing role. The patient had been on steroids for about a week before the repeat bone marrow biopsy and then his blood cultures were taken a few days later. Lupus can also place patients at increased risk of infection; however, rheumatology believed this patient not to have lupus and prednisone was stopped. He has not had any further symptoms following his successful treatment of his leishmaniasis to suggest that he indeed had lupus. Leishmaniasis has been well documented as an agent causing cell-mediated immunosuppression without a definitive mechanism. In experimental hamster models, there is a 40% reduction in CD4+ T cells (8). Patients with active leishmaniasis can have negative intradermal skin tests for Leishmania antigen and also have decreased the production of interleukin 2, 10 and gamma- interferon (9). After completion of treatment, they often become responsive to Leishmania antigen (7). Observational studies have demonstrated that secondary bacterial infections are often implicated as the cause of death in patients with VL (10).

C. neoformans is an opportunistic infection that became more common following the HIV epidemic. The yeast lives in the soil worldwide, and disease is believed to start with inhalation of the fungus, but the primary pulmonary infection often goes unnoticed in immunocompetent patients (11,12). Those with HIV become more prone to Cryptococcus when their CD4 count drops below 100 cells/mm3. Increased rates of cryptococcosis have also been documented in patients with isolated CD4 T cell lymphocytopenia, suggesting that the CD4 count, regardless of the cause, is an important contributor to disease (12).

In conclusion, we present a case of cryptococcosis likely resulting from immunosuppression from VL. It is important to recognize that chronic disseminated infections other than HIV can be a source of clinically significant immunosuppression. In treating patients with VL, clinicians should be aware of potential co-infection.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Kevin Woodward, Chris Hillis, Mark Crowther, Irwin Walker, Catherine Ross, Ronen Foley, and the National Reference Centre for Parasitology at McGill University.

Competing Interests:

Dr Yamamura reports advisory board roles with Merck and Verity outside the submitted work.

Ethics Approval:

N/A

Informed Consent:

N/A

Registry and the Registration No. of the Study/Trial:

N/A

Animal Studies:

N/A

Funding:

No funding was received for this work.

Peer Review:

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Awasthi A,Mathur RK,Saha B. Immune response to Leishmania infection. Indian J Med Res. 2004;119(6):238–58. Medline: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Griensven J,Diro E. Visceral leishmaniasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26(2):309–22. 10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.005. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cota GF,Gomes LI,Pinto BR, et al. Dyarrheal syndrome in a patient co-infected with Leishmania infantum and Schistosoma manosoni. Case Rep Med. 2012:Article ID 240512. 10.1155/2012/240512. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozubowski L,Heitman J, Profiling a killer the development of Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36(1):78–94. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00286.x. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofman V,Brousset P,Mougneau E, et al. Immunostaining of visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum using monoclonal antibody (19–11) to the Leishmania homologue of receptors for activated C-kinase. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;120(4):567–74. 10.1309/R3DK4MR3W6E5PH17. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sangoi AR,Rogers WM,Longacre TA,Montoya JG,Baron EJ,Banaei N. Challenges and pitfalls or morphologic identification of fungal infections in histologic and cytologic specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131(3):364–75. 10.1309/AJCP99OOOZSNISCZ. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCall LI,Zhang WW,Matlashewski G, Determinants for the development of visceral leishmaniasis disease. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(1):e1003053. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003053. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto H,Lindoso JA. Immunity and immunosuppression in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37(4):615–23. 10.1590/S0100-879X2004000400020. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvalho EM,Bacellar O,Barral A,Badaro R,Johnson WD. Antigen-specific immunosuppression in visceral leishmaniasis is cell mediated. J Clin Invest. 1989;83(3):860–4. 10.1172/JCI113969. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasyar N,Alborzi A,Pouladfar GR. Evaluation of serum procalcitonin levels for diagnosis of secondary bacterial infections in visceral leishmaniasis patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(1):119–21. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0079. Medline: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silvasangeetha K,Harish BN,Sujatha S,Parija SC,Dutta TK. Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis diagnosed by blood culture. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25(3):282–4. 10.4103/0255-0857.34777. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powderly W. Current approach to the acute management of cryptococcal infections. J Infect. 2000;41(1):18–22. 10.1053/jinf.2000.0696. Medline: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]