Abstract

The main objective of this research paper is to examine the influence of perceived support (i.e., organizational support and social support) on life satisfaction (i.e., current and anticipated life satisfaction), which is hypothesized to increase restaurant employees’ loyalty organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and decrease their intentions to leave the restaurant industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the moderating effects of employees’ resilience and employment status are also examined. Analyzing the responses of 609 restaurant employees using structural equation modeling (SEM), findings revealed that all direct effects were supported, except for the effect of anticipated life satisfaction on intention to leave the restaurant industry. Lastly, the moderating role of resilience in the relationships between current life satisfaction and restaurant employees’ loyalty OCB and intentions to leave the industry was confirmed. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed in detail.

Keywords: Organizational and social support, Life satisfaction, Loyalty organizational citizenship behavior, Intentions to leave, Resilience, Employment status

1. Introduction

It will come as no surprise that satisfied workers tend to be more productive (Bellet et al., 2019). The support that employees receive from their organizations, known as perceived organizational support (POS), has been shown to have a strong positive effect on overall job satisfaction (Riggle et al., 2009) and organizational loyalty (Kim et al., 2004, Susskind et al., 2000), as well as a negative influence on turnover intentions (Cho et al., 2009). Perceived social support (PSS), on the other hand, is the support that an individual receives from friends, family, and acquaintances and, while more subjective than POS, has been considered to be especially important in difficult situations (Zimet et al., 1988).

Life satisfaction, being the self-perceived evaluation and outlook that an individual has about their overall life (Pavot and Diener, 2008), was shown to be an integral component of a person’s subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1985), and was found not only to be influenced by an individual’s current situation, but also by the evaluation of anticipated life satisfaction (Baranik et al., 2019). While POS was previously found to have a positive effect on job satisfaction, the latter construct, in turn, has been linked to the life satisfaction of restaurant employees (Hight and Park, 2018). This is particularly pertinent during stressful times, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, with two out of three restaurant workers having lost their jobs or been furloughed, equating to eight million laid-off restaurant workers by April 2020 (National Restaurant Association, 2020). It is at such times that the presence of positive support systems could help individuals to maintain a positive outlook on their present and projected life satisfaction.

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its first United States case reported in January 2020 (Holshue et al., 2020), had resulted in around 200,000 U.S. deaths by early October 2020 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), with most states having mandated closing or restricting foodservice establishments by April 2020 (Restaurant Law Center, 2020). Although by June 2020 most states had started to permit restaurants to reopen, albeit with various restrictions (Sontag, 2020), many consumers reported being unlikely to dine at restaurants due to concerns about the COVID-19 virus, and by September 2020 over 100,000 restaurants had closed (National Restaurant Association, 2020). These health concerns have resulted in a more stressful work environment for those restaurant employees still working, as many of them are concerned about contracting the virus and spreading it to their family members and other acquaintances (Simonetti, 2020).

Given the alarming statistics on job losses in the restaurant industry, coupled with altered working conditions, the question of organizational loyalty arises. The concept of loyalty organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), introduced by Van Dyne et al. (1994), reflects an employee’s allegiance to the organization that he/she works for through the promotion of the organization’s interests to outsiders (Bettencourt et al., 2001). Previous studies have found that employees’ organizational commitment had stronger effects on citizenship behaviors among part-time employees than full-time workers (Cho and Johanson, 2008) while, in a hospitality context, OCB was found to affect job satisfaction (Jung and Yoon, 2015), organizational identification (Teng et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2017), depersonalization (Kang and Jang, 2019), positive psychological capital (Lee et al., 2017), and positive group affective tone (Tang and Tsaur, 2016a). However, no previous study is known to have investigated the relationship between employees’ life satisfaction and loyalty OCB in a restaurant setting, and certainly, not during a stressful period such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given the nuanced nature of human responsiveness to external stimuli and, by extension, the complexities characterizing the interaction between the organization and the employee, this study has adopted a multi-theoretical framework to serve as the foundation of the hypotheses offered. By drawing from the social exchange theory (SET) (Emerson, 1976), organizational support theory (OST) (Eisenberger et al., 1986), and spillover theory (Sirgy et al., 2001), the current study sets out to investigate the effects of POS and PSS on current and future life satisfaction and how these, in turn, affect loyalty OCB and intentions to leave the restaurant industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. While several studies in the hospitality literature have investigated the relationship between employees’ job satisfaction and short-term turnover intentions (e.g., Bufquin et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2015; Chen and Wang, 2019; Ferreira et al., 2017; Hight and Park, 2019), few have examined the relationship between employees’ life satisfaction and intentions to leave their career or industry. Further, no studies have done so during a crisis such as a pandemic.

Additionally, the moderating effects of resilience and employment status are also investigated. Resilience refers to an individual’s ability to maintain composure and normal functioning in the face of adversity, conflict, or change (Luthans, 2002), particularly relevant during the challenging conditions of the pandemic. Employment status refers to those restaurant employees still working versus the large number of workers that have been furloughed during the pandemic, as working and resilient employees may benefit more from the positive effects of life satisfaction on loyalty OCB and industry turnover intentions than their furloughed and psychologically vulnerable counterparts.

The current study, therefore, sets out to answer the following research questions:

RQ 1: What is the influence of support systems (i.e., POS and PSS) on life satisfaction?

RQ 2: Does life satisfaction increase restaurant employees’ loyalty organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and decrease their intentions to leave the restaurant industry during the COVID-19 pandemic?

RQ 3: Does employees’ resilience and employment status (i.e., “working” versus “furloughed” employees) moderate the relationship between life satisfaction and loyalty OCB?

RQ 4: Does employees’ resilience and employment status (i.e., “working” versus “furloughed” employees) moderate the relationship between life satisfaction and intentions to leave the restaurant industry?

The obtained results will assist restaurant employees, who are still working or have been furloughed during the pandemic, to find important solutions regarding social support systems and psychological resources, which may improve their life satisfaction in both the short and long terms. Such attitudinal outcomes are hypothesized to lead them to adopt further organizational citizenship behaviors and maintain their willingness to remain working in the restaurant sector. As a result, restaurateurs will be able to apply the study’s findings in their day-to-day interactions with employees, so that the latter can flourish within their restaurant companies.

2. Literature review

2.1. Perceived organizational support and perceived social support

According to OST, employees tend to develop a generalized perception regarding the extent to which their employer cares about their welfare (Eisenberger et al., 1986, Kurtessis et al., 2015). These perceptions are based on employees’ confidence that the organization values their contribution and is willing to meet their socioemotional needs through various rewards. Along these lines, POS is related to employees' overall perceptions of the amount of concern shown by the organization for their well-being and the value of their contributions (Guchait et al., 2015). Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002) conducted a meta-analysis of POS and indicated that three major categories of favorable treatment received by employees (i.e., fairness, supervisor support, and organizational rewards and favorable job conditions) were associated with POS. Employees generally seek a reciprocal balance by basing their attitudes and behaviors on the organization's support (Eisenberger et al., 1990). Hence, employees believe their performance will be rewarded in the future as their reciprocal expectancy is increased by POS (Eisenberger et al., 2001).

Accordingly, OST facilitates the observation of the employee-organization relationship from the employees’ viewpoint and, hence, has been of considerable interest in organizational behavior literature. Based on another meta-analysis by Kurtessis et al. (2015), OST successfully predicted both the antecedents and consequences of POS. The study found the antecedents of POS to be leadership, employee–organization context, human resource practices, and working conditions, while employee’s orientation toward the organization and work, employee performance, and well-being were identified as consequences of POS.

Based on the norms of reciprocity, POS has been associated with lower turnover intentions (Cho et al., 2009) and higher organizational loyalty (Kim et al., 2004, Susskind et al., 2000). Furthermore, POS was also found to be related to a stronger customer orientation demonstration by employees (Chow et al., 2006) and improved job performance (Karatepe, 2012). Likewise, POS was linked to beneficial outcomes regarding employees (e.g., job satisfaction, affective commitment, positive mood) and organizations (e.g., performance, lessened withdrawal behaviors) (Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002).

Also, there has been extensive research on the outcomes of a strong social network. For example, social support was found to have strong relationships with physical well-being, such as physical health and mortality, including sub-factors of disease, disease maintenance, the severity of diseases, and disease recovery (Seeman, 1996). Further, social support has been found to have a negative relationship with mental health, such as loneliness, depression, and emotional well-being (Wang et al., 2018). Finally, social support has a significant influence on physiological health, which is often a precursor to many of the physical and mental ailments noted above (Seeman, 1996).

Perceived social support (PSS), on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of the amount of support available to him/her from family, friends, and anyone within their social circle. This can include immediate family members (e.g., a spouse or parent) or personal acquaintances (e.g., close friends and confidants) (Uchino, 2004). As a construct, PSS is distinct for several reasons. First, this construct refers to the subjective view of an individual; hence, actual consumption or receipt of the support is not measured. This is because the perceived quantity and quality of one’s social support is sufficient to influence various individual factors, such as loneliness, self-esteem, and self-efficacy (Uchino, 2009). As a result, the perception of a strong social support group can become a tool to alleviate stressful situations. For example, a person with the perception of a strong social network may overcome initial feelings of inadequacy in the face of a difficult task or situation (Zimet et al., 1988), such as a pandemic. POS and PSS may also influence life satisfaction.

2.2. Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction is the self-perceived evaluation and outlook that individuals have about their overall lives (Pavot and Diener, 2008). Researchers have used this construct as a nuanced measure of satisfaction that results from an individual's decisions across various domains of his/her life, such as satisfaction with work, family, and relationships (Cain et al., 2018, Demerouti et al., 2005, Peterson et al., 2005). In general, scholars have distinguished two distinct perspectives of life satisfaction: a top-down approach and a bottom-up approach (Erdogan et al., 2012). The top-down approach to life satisfaction analyzes how an individual’s psychological characteristics, such as emotional stability, can influence perceptions of life satisfaction (Steel et al., 2008). Relevant to the current study, the bottom-up approach assesses life satisfaction as the outcome of satisfaction across various life domains, including work, family, and health (Erdogan et al., 2012).

Accordingly, the concept of spillover can also be applied in this study. Prior research has found that happenings (i.e., interactions, attitudes, emotions) from one domain of an individual’s life, such as work domain, can impact or spillover into another domain, such as home life, financial life, or social life (Ragland and Ames, 1996). There are two types of spillover, namely horizontal and vertical. Horizontal spillover refers to the impact that one life domain can have on a neighboring life domain (Sirgy et al., 2001). When analyzing spillover in the context of an individual’s well-being, researchers have pointed out that the concept of bottom-up vertical spillover is more appropriate, because the bottom-up spillover approach suggests that satisfaction or dissatisfaction within the lower ranking domains (i.e., family, social, job) will vertically spillover into the dominant domain (i.e., life satisfaction) (Sirgy et al., 2001). Research within this perspective has consistently found that positive perceptions across various life domains increase an individual’s overall life satisfaction and vice versa (Demerouti et al., 2005, Grzywacz and Marks, 2000).

Furthermore, prior research has identified that life satisfaction is an integral component of a person’s subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1985), which has recently gained the attention of national leaders who concluded that improving an individual’s life satisfaction could assist in creating and maintaining an overall positive disposition about one's current and future prospects; and such prospects could, in turn, influence the overall welfare and productivity of a nation (Diener et al., 2013). Given the current pandemic and its negative impacts on the hospitality industry, especially the restaurant industry, it is important to understand which antecedents can influence life satisfaction and the overall well-being of restaurant employees.

Researchers have found that life satisfaction is not solely influenced by one's current situation, but also by the perception of anticipated life satisfaction. In other words, assessing an individual's true satisfaction with life requires an understanding of their current view of life in conjunction with their outlook about their future life. Prior research on stressful situations, such as economic recessions, layoffs, and furloughs, found that employees tend to experience a resource loss which, in turn, negatively affects perceptions of optimism about their current and future psychological state (Baranik et al., 2019). However, in the presence of a positive support system from employers and social circles, individuals could maintain a positive outlook during times of hardship, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, POS has been linked with positive attitudinal outcomes, such as affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Kurtessis et al., 2015), and job satisfaction has been found to have a positive relationship with the life satisfaction of restaurant employees (Hight and Park, 2018). In addition, prior research has demonstrated that PSS is associated with lower levels of depression and higher levels of life satisfaction (Uchino, 2004). Since POS and PSS measure an individual’s perception, rather than actual receipt of support, it is logical to assume that if someone believes they have a strong support system, which may enhance their current life satisfaction, the same support system will probably play a role in their anticipated life satisfaction. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a

Perceived organizational support will positively affect employees’ current life satisfaction.

H1b

Perceived organizational support will positively affect employees’ future life satisfaction.

H2a

Perceived social support will positively affect employees’ current life satisfaction.

H2b

Perceived social support will positively affect employees’ future life satisfaction.

2.3. Loyalty organizational citizenship behavior

Social exchange theory (SET) refers to a process where one actor initiates an interaction, either positive or negative, with another actor (Emerson, 1976). In turn, the receiving actor reacts with a reciprocating response that usually mirrors the type of treatment received (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Therefore, SET posits that, in the presence of a positive initiating interaction, receivers will respond in a similar, positive manner (Gouldner, 1960), and that there is an implicit obligation for employees to return a favor after receiving a favor or benefit from another person or group (Blau, 1964). Thus, employees who perceive a high-quality social exchange relationship with their employer could exhibit behaviors deemed preferable by their employer, such as increased instances of trust and loyalty (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005).

This logic is similar to the findings of the person-organization (P-O) fit theory, which posits that individuals who find congruence between their personal values and those of their employer illustrate more robust organizational commitment levels (Verquer et al., 2003); and of the person-situation theory, which posits that the interaction of personal traits and organizational situations can predict an employee’s behavior in the work environment (Kenrick and Funder, 1988). Thus, when a firm offers support or incentives that enable an employee to meet their professional or personal objectives, it is logical to suggest that employees may exhibit positive behavioral outcomes such as organizational commitment (Stewart and Barrick, 2004). Further, Bagozzi’s (1992) attitude theory posits that the cognitive evaluations of events, outcomes, and situations precede affective reactions, which in turn influence an individual’s intentions and behaviors. It implies that organizations’ support of their employees can lead to favorable outcomes such as job satisfaction, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors.

The concept of loyalty organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) was first introduced by Van Dyne et al. (1994) and later referred to as “loyal boosterism” (Moorman et al., 1998) and “allegiance” (Borman and Motowidlo, 1993), among other terms. Loyalty OCB reflects an employee’s allegiance to the organization that he/she works for, through the promotion of the organization’s interests and image to outsiders (Bettencourt et al., 2001). Other types of service-oriented OCBs do exist, such as service delivery OCB and participation OCB. However, because employees’ job attitudes account for the most variance in loyalty OCB (Bettencourt et al., 2001), and given that the current study is assessing the relationship between employees’ life satisfaction and OCB, only loyalty OCB will be taken into consideration. Loyalty OCB is an interesting concept to examine, as it affects a variety of work-related and performance outcomes, such as service quality (Bienstock et al., 2003), employees’ continuance of employment, and intention to leave for monetary incentives (Cho and Johanson, 2008), as well as customer loyalty (Castro et al., 2004) and restaurants’ inspection scores (Bienstock et al., 2003).

It is thus hypothesized that restaurant employees, who receive sufficient organizational and social support, will tend to experience increased life satisfaction in both the short and long terms. This, in turn, will lead them to adopt improved loyalty OCB at their restaurants. Such propositions support prior findings regarding the effect of life satisfaction on job performance (e.g., Duckworth et al., 2009; Jones, 2006; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). However, to the authors’ knowledge, no study thus far has assessed the relationship between employees’ life satisfaction and loyalty OCB in a restaurant setting, and certainly not during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a

Employees’ current life satisfaction will positively affect employees’ loyalty organizational citizenship behavior.

H3b

Employees’ future life satisfaction will positively affect employees’ loyalty organizational citizenship behavior.

2.4. Intentions to leave the industry

When analyzing why employees remain loyal to their employer and their career, scholars have often drawn from the attachment theory, which suggests that individuals possess innate tendencies to attract and remain close with other supportive figures who can help alleviate physical or psychological stressors (Mikulincer et al., 2002). While originally developed to understand why individuals become attached to others, scholars have recently used this theory to describe how attachment can extend beyond individual relationships to relationships with companies (Yip et al., 2018). This logic is similar to the social information processing theory, which suggests that an organization’s social environment may influence employee attitudes and behaviors toward the organization (Salancik and Pfeffer, 1978). Hence, if employees perceive that their employer provides adequate support within the workplace, especially during times of distress, they are likely to exhibit favorable behavioral outcomes, including organizational commitment and loyalty (Wang et al., 2014).

While much of the existing hospitality literature related to satisfaction and turnover has focused on the relationship between employees’ job satisfaction and short-term turnover intentions (e.g., Bufquin et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2015; Chen and Wang, 2019; Ferreira et al., 2017; Hight and Park, 2019), few studies have examined the relationship between employees’ life satisfaction (i.e., current and future) and intentions to leave their career or industry. For instance, in a seminal study by Ghiselli et al. (2001), restaurant employees’ life satisfaction was linked with an intention to imminently leave their current employment. Likewise, in a study by Erdogan et al. (2012), a meta-analysis revealed statistically significant negative average weighted correlations between life satisfaction and immediate turnover intentions. Hence, it is reasonable to suggest that if employees receive sufficient organizational and social support, they will tend to experience increased current and anticipated life satisfaction, which will lower their probability of wanting to leave their careers in the restaurant industry. Based on the aforementioned literature and theoretical frameworks, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a

Employees’ current life satisfaction will negatively affect employees’ intentions to leave the restaurant industry.

H4b

Employees’ future life satisfaction will negatively affect employees’ intentions to leave the restaurant industry.

2.5. The moderating effect of resilience

Since the onset of COVID-19, many restaurants have shifted business functions to minimize the spread of the virus. Although over 100,000 US restaurants had closed by September 2020, many of those still operating have survived by quickly adapting and shifting their business model to focus on take-out, limited dine-in offerings, and new menus, all while maintaining recommended social distancing guidelines (National Restaurant Association, 2020). Adapting to challenging conditions is something that scholars have sought to explore, since individuals vary in their response to external stimuli, especially in situations that are deemed stressful or traumatic. While analyzing how a person responds to stressful situations, scholars have noted that resilience can explain why some individuals seem to adapt to stressful situations better than others (Luthans et al., 2006). Given that resilience can impact an individual’s reaction and performance in the face of a challenge (Luthans, 2002), this study sought to identify whether restaurant employees’ resilience may impact their behavioral outcomes (i.e., loyalty OCB and intention to leave the restaurant industry).

Resilience refers to when individuals maintain composure and normal functioning in the presence of adversity, conflict, and in some cases, positive changes (Luthans, 2002). Resilience is considered to be a psychological resource, and those who exhibit higher levels of resilience tend to exhibit more favorable behavioral outcomes in the workplace, such as organizational commitment, job satisfaction, well-being, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Paul et al., 2016). Furthermore, prior research has found that resilient individuals exhibit increased job satisfaction, better mental health, and the perception of an agreeable work-life balance (Hudgins, 2016, Paul et al., 2016). In times of workplace duress, individuals who demonstrate high levels of resilience exhibit increased loyalty toward their organization (Luthans et al., 2006), because resilient individuals seek out successful ways to adjust to workplace challenges, which in turn gives them a deeper meaning about their work, thus creating an intensified interest in the firm (Paul et al., 2016).

However, an individual with strong psychological resources, including resilient behavior, will not always illustrate loyalty to an organization if the organization has broken a psychological contract with the employee. In other words, if an employee does not feel their employer is providing adequate support during times of duress, it is plausible to suggest that a resilient employee could seek alternate employment or leave the industry altogether. This notion has been confirmed in prior research regarding voluntary job turnover self-efficacy, where employees who are comfortable with adapting to new situations are more likely to seek an alternative employer (Moynihan et al., 2003). With the challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, it implies that even though employees who are satisfied with their life (i.e., current and future) tend to exhibit a high level of OCB loyalty or low level of intentions to leave the industry, the impact of life satisfaction on these behaviors can differ based on their level of resilience. Given these prior findings, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H5a

Employees' resilience will moderate the relationship between employees' current life satisfaction and employees' loyalty organizational citizenship behavior.

H5b

Employees' resilience will moderate the relationship between employees' future life satisfaction and employees' loyalty organizational citizenship behavior.

H5c

Employees' resilience will moderate the relationship between employees' current life satisfaction and employees' intentions to leave the restaurant industry.

H5d

Employees' resilience will moderate the relationship between employees' future life satisfaction and employees' intentions to leave the restaurant industry.

2.6. The moderating effect of employment status

To stem the spread of the virus in the U.S., restrictions have included orders to stay at home, travel limitations, social distancing, and the temporary closure of many businesses in the hospitality sector (Bartik et al., 2020). In fact, by late April 2020, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had ordered the temporary closing or restricting of foodservice establishments in response to COVID-19, with most restricting restaurants to take-out/curbside pickup and delivery only (Restaurant Law Center, 2020). Given the concerning statistics regarding such temporary restaurant closures and limited operations, and consequential furloughs (Pesce, 2020), this study sets out to examine the moderating effects of employment status (i.e., “working” versus “furloughed” employees) on the relationships among employees’ life satisfaction, loyalty OCB and intentions to leave the restaurant industry.

Except for a study by Cho and Johanson (2008), which concluded that employees’ organizational commitment had stronger effects on citizenship behaviors among part-time employees than full-time workers; and a study by Stamper and Van Dyne (2001), which demonstrated that part-time employees exhibited less helping organizational citizenship behavior than full-time employees, no other hospitality study has looked at the moderating effects of employment status on the relationships between employees’ attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. More specifically, empirical research still needs to be performed in order to examine the moderating effect of employment status (i.e., “working” versus “furloughed” employees) between employees’ life satisfaction and loyalty OCB.

Along these lines, a seminal study by Aquino et al. (1996) found that the number of hours worked at a paying job was directly related to higher levels of life satisfaction. Based on SET (Blau, 1964), the employment status of restaurant employees may play a significant role in the positive relationship between life satisfaction and OCB loyalty, such that a working employee will benefit more from the positive effect of life satisfaction on loyalty OCB than his/her furloughed counterpart, given that the former still has a job despite the massive unemployment resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (Pesce, 2020).

The same rationale is suggested for the moderating effect of employment status on the negative relationship between employees’ life satisfaction and intentions to leave the restaurant industry. Based on SET (Blau, 1964), we hypothesize that the negative effect of life satisfaction on industry turnover intentions will be more significant for working employees than furloughed employees, since the latter are currently not working and, as a result, may want to look for jobs in other industries. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a

Employees’ employment status will moderate the relationship between employees’ current life satisfaction and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior loyalty.

H6b

Employees’ employment status will moderate the relationship between employees’ future life satisfaction and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior loyalty.

H6c

Employees’ employment status will moderate the relationship between employees’ current life satisfaction and employees’ intentions to leave the restaurant industry.

H6d

Employees’ employment status will moderate the relationship between employees’ future life satisfaction and employees’ intentions to leave the restaurant industry.

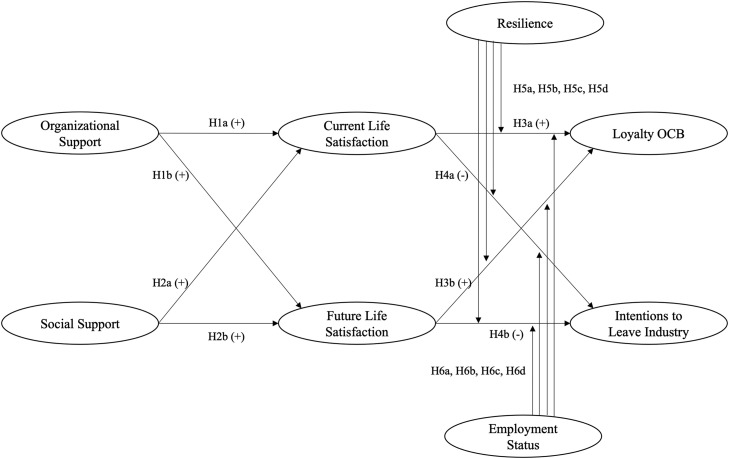

The conceptual model of this research is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection

To achieve the main objectives of this study, data were collected from a sample of non-managerial restaurant employees who were currently working or had been furloughed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and who were at least 18 years of age. The questionnaire was developed using the Qualtrics online survey platform and distributed to participants by an online marketing company. For data collection, a self-selection sampling method was utilized. To minimize potential sampling bias, each respondent was asked to answer screening questions to ensure the qualifying criteria of employment status and age. Similar to previous investigations (e.g., Tussyadiah et al. 2020), attention checks were added to obtain quality data. After removing respondents with missing data, as well as those who failed the screening questions and attention checks, 609 samples were utilized for the analysis out of a total of 922 questionnaires, representing a response rate of 66%.

3.2. Measures

Perceived organizational support was measured using the shorter 8-item version of the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS), as recommended by Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002), while PSS was measured using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) developed by Zimet et al. (1988). Current and future life satisfaction was measured using the Temporal Satisfaction with Life Scale (TSWLS) created by Pavot et al. (1998). A 4-item scale adapted from Bettencourt et al. (2001) was used to measure loyalty service-oriented OCB, while intentions to leave the restaurant industry was based on measurement items from a study by Farkas and Tetrick (1989). Finally, resilience was measured using the 10-item scale developed by Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007), and employment status was coded as a binary variable (0 = working and 1 = furloughed). A seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) was used for all constructs, as suggested by Churchill (1979). Further, sociodemographic questions were also included at the end of the questionnaire.

3.3. Data analysis

As suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (1992), the current investigation adopted a two-step approach, starting with a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) testing the validity of each construct. In the second step, hypotheses were tested applying structural equation modeling (SEM). Furthermore, multi-group analyses through invariance tests were conducted to verify the potential moderation effects proposed by this research.

4. Results

4.1. Sample profile

Among 609 respondents, 231 were furloughed and 378 were still working in the restaurant industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most were male (52.5%) while 46.3% were female, and aged between 19 and 39 (75.2%), followed by those aged 40–49 (17.9%). Moreover, 49.6% indicated they had a 4-year college degree and 22.2% held a master’s degree. Most respondents worked in front of the house (50.1%), while 26.6% reported working in back of the house, and 23.3% in administrative positions. In terms of tenure, 65.8% had been working at their company for 1–5 years, 17.9% more than 5 years, and 16.2% less than 12 months. The majority of restaurant employees reported having an annual household income between $30,000 and $59,999 (46.3%), followed by those who received between $60,000 and $79,999 (18.7%), and less than $29,999 (18.6%). Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 320 | 52.5 |

| Female | 282 | 46.3 | |

| Other | 7 | 1.2 | |

| Age | 19–29 | 183 | 30.0 |

| 30–39 | 275 | 45.2 | |

| 40–49 | 109 | 17.9 | |

| 50–59 | 29 | 4.8 | |

| 60 or higher | 13 | 2.1 | |

| Annual | Less than $10,000 | 9 | 1.5 |

| Household | $10,000 to $19,999 | 34 | 5.6 |

| Income | $20,000 to $29,999 | 70 | 11.5 |

| $30,000 to $39,999 | 76 | 12.5 | |

| $40,000 to $49,999 | 90 | 14.8 | |

| $50,000 to $59,999 | 116 | 19 | |

| $60,000 to $69,999 | 58 | 9.5 | |

| $70,000 to $79,999 | 56 | 9.2 | |

| $80,000 to $89,999 | 25 | 4.1 | |

| $90,000 to $99,999 | 25 | 4.1 | |

| $100,000 to $149,999 | 35 | 5.7 | |

| $150,000 or more | 15 | 2.5 | |

| Education | High school or equivalent | 62 | 10.2 |

| 2-year college | 96 | 15.8 | |

| 4-year college or university | 302 | 49.6 | |

| Master's degree (MS) | 135 | 22.2 | |

| Doctoral degree (Ph.D.) | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Professional degree (MD, JD, etc.) | 9 | 1.5 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Role | Front of the house | 305 | 50.1 |

| Back of the house | 162 | 26.6 | |

| Administration | 142 | 23.3 | |

| Tenure | Less than 6 months | 21 | 3.4 |

| 6 – 12 months | 78 | 12.8 | |

| 1 – 2 years | 201 | 33 | |

| 3 – 5 years | 200 | 32.8 | |

| 5 – 10 years | 87 | 14.3 | |

| 11 – 15 years | 11 | 1.8 | |

| More than 15 years | 11 | 1.8 | |

| Total | 609 | 100.00 |

4.2. Measurement model

Prior to analyzing the structural model, it was necessary to examine whether a common method bias exists, since all data are self-reported and collected through the same questionnaire with a cross-sectional research design (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986, Podsakoff et al., 2003). Exploratory factor analysis by principal components factor with Varimax Rotation was conducted. The results suggested that six distinctive factors (i.e., Eigenvalue greater than 1) were identified and explained 74.169% of the total variance ( Table 2). Further, Harman’s single factor testing was conducted. The single factor explained 40.429% of total variance, which is lower than 50% cutoff (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In other words, it can be concluded that common method variance is not an issue for this study.

Table 2.

Common method bias test.

| Factor | Initial Eigenvalues |

Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Eigenvalue | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 14.15 | 40.429 | 40.429 | 7.806 | 22.303 | 22.303 |

| 2 | 4.207 | 12.021 | 52.450 | 6.789 | 19.398 | 41.700 |

| 3 | 3.286 | 9.389 | 61.839 | 3.760 | 10.742 | 52.442 |

| 4 | 2.248 | 6.422 | 68.261 | 3.360 | 9.600 | 62.042 |

| 5 | 1.054 | 3.012 | 71.273 | 3.200 | 9.142 | 71.184 |

| 6 | 1.014 | 2.896 | 74.169 | 1.045 | 2.984 | 74.169 |

CFA was conducted to confirm the validity of each construct ( Table 3). First, the model χ2 was significant at 1% level. However, since χ2 value is known as sensitive due to the sample size (Hair et al., 2010), it was necessary to consider other goodness-of-fit indices. Indices showed that the model fitted the data well (TLI = 0.935; CFI = 0.941; RMSEA = 0.058).

Table 3.

Measurement model.

| Estimate | S.E. | t-value | AVE | CR | Alpha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational | pos_1 | 0.875 | 0.684 | 0.928 | 0.928 | ||

| Support | pos_2 | 0.854 | 0.038 | 28.584*** | |||

| pos_4 | 0.846 | 0.036 | 28.047*** | ||||

| pos_5 | 0.829 | 0.038 | 27.022*** | ||||

| pos_6 | 0.837 | 0.037 | 27.532*** | ||||

| pos_7 | 0.713 | 0.036 | 21.030*** | ||||

| Social | pss_1 | 0.828 | 0.594 | 0.946 | 0.949 | ||

| Support | pss_2 | 0.805 | 0.042 | 23.513*** | |||

| pss_3 | 0.712 | 0.041 | 19.746*** | ||||

| pss_4 | 0.747 | 0.042 | 21.105*** | ||||

| pss_5 | 0.803 | 0.042 | 23.410*** | ||||

| pss_6 | 0.780 | 0.039 | 22.500*** | ||||

| pss_7 | 0.742 | 0.042 | 20.891*** | ||||

| pss_8 | 0.766 | 0.043 | 21.875*** | ||||

| pss_9 | 0.753 | 0.042 | 21.322*** | ||||

| pss_10 | 0.819 | 0.043 | 24.156*** | ||||

| pss_11 | 0.722 | 0.042 | 20.155*** | ||||

| pss_12 | 0.763 | 0.041 | 21.754*** | ||||

| Life Satisfaction | life_current1 | 0.791 | 0.721 | 0.928 | 0.924 | ||

| (Current) | life_current2 | 0.875 | 0.038 | 24.839*** | |||

| life_current3 | 0.899 | 0.040 | 25.779*** | ||||

| life_current4 | 0.888 | 0.038 | 25.374*** | ||||

| life_current5 | 0.786 | 0.036 | 21.500*** | ||||

| Life Satisfaction | life_future2 | 0.832 | 0.725 | 0.913 | 0.913 | ||

| (Future) | life_future3 | 0.856 | 0.040 | 25.689*** | |||

| life_future4 | 0.884 | 0.039 | 26.962*** | ||||

| life_future5 | 0.832 | 0.039 | 24.598*** | ||||

| Loyalty OCB | loyalty_ ocb_1 | 0.867 | 0.756 | 0.925 | 0.925 | ||

| loyalty_ ocb_2 | 0.858 | 0.035 | 28.145*** | ||||

| loyalty_ ocb_3 | 0.869 | 0.035 | 28.801*** | ||||

| loyalty_ ocb_4 | 0.883 | 0.033 | 29.677*** | ||||

| Intentions to Leave Industry | int_1 | 0.921 | 0.743 | 0.920 | 0.926 | ||

| int_2 | 0.877 | 0.030 | 31.248*** | ||||

| int_3 | 0.827 | 0.033 | 27.563*** | ||||

| int_4 | 0.819 | 0.033 | 27.057*** |

Model fit: χ2 = 1620.217, df = 537, p < .01, NFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.935, CFI = 0.941, RMSEA = 0.058.

*** p < .01

Second, convergent validity was tested. Standardized factor loadings were examined, and all factor loadings were higher than the minimum threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010). The values for average variance extracted (AVE) and construct reliability (CR) were calculated, and they all exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.70 suggested by Hair et al. (2010). To test for internal consistency, Cronbach’s α was calculated for each construct, and results suggested that all α values were higher than 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978).

Third, discriminant validity was tested by comparing AVE values with squared correlations between each construct as suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Results suggested that all AVE values were greater than the squared correlations between constructs, implying that discriminant validity was confirmed ( Table 4).

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loyalty OCB | (0.756) | |||||

| Organizational Support | 0.219 | (0.684) | ||||

| Social Support | 0.356 | 0.234 | (0.594) | |||

| Life Satisfaction (Current) | 0.241 | 0.258 | 0.573 | (0.721) | ||

| Life Satisfaction (Future) | 0.650 | 0.211 | 0.358 | 0.282 | (0.725) | |

| Intentions to Leave Industry | 0.069 | 0.013 | 0.024 | 0.003 | 0.095 | (0.743) |

Note: The diagonal numbers in parentheses indicate the AVE. The remaining numbers are squared correlations.

4.3. Hypotheses testing

In order to test the proposed hypotheses, this study utilized a structural equation model (SEM). The goodness-of-fit indices suggested that the model fitted the data appropriately (χ2 = 1862.268, p < .01; NFI = 0.902; TLI = 0.921; CFI = 0.928; RMSEA = 0.063). The SEM results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Structural model.

| Hypotheses | Estimate | t-value | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Org. Support | → | LS (Current) | 0.507 | 11.741*** | Supported |

| H1b | Org. Support | → | LS (Future) | 0.335 | 7.699*** | Supported |

| H2a | Soc. Support | → | LS (Current) | 0.256 | 6.411*** | Supported |

| H2b | Soc. Support | → | LS (Future) | 0.349 | 7.964*** | Supported |

| H3a | LS (Current) | → | Loyalty OCB | 0.529 | 8.476*** | Supported |

| H3b | LS (Future) | → | Loyalty OCB | 0.132 | 2.209** | Supported |

| H4a | LS (Current) | → | Leave Industry | -0.303 | -4.154*** | Supported |

| H4b | LS (Future) | → | Leave Industry | 0.167 | 2.285** | Not supported |

Model fit: χ2 = 1862.268, df = 540, p < .01, NFI = 0.902, TLI-0.921, CFI = 0.928, RMSEA = 0.063

Note: ***p < .01, **p < .05

First, it was hypothesized that organizational support would have a significant positive impact on current life satisfaction (H1a) and future life satisfaction (H1b). Results suggested that organizational support had a significant positive influence on the current life satisfaction (βOrg. Support → LS (Current) = 0.507, p < .01) and future life satisfaction (βOrg. Support → LS (Future) = 0.335, p < .01) of restaurant employees. Thus, both H1a and H1b were supported. Second, social support was hypothesized to have a positive influence on both life satisfaction dimensions. Results showed a significant positive influence of social support on both life satisfaction dimensions (βSoc. Support → LS (Current) = 0.256, p < .01; βSoc. Support → LS (Future) = 0.349, p < .01), thus supporting H2a and H2b. Third, it was hypothesized that current and future life satisfaction would have a significant positive influence on loyalty OCB (H3a and H3b). Results confirmed that current life satisfaction had a significant positive impact on loyalty OCB (βLS (Current) → Loyalty OCB = 0.529 p < .01), and that future life satisfaction had a significant positive influence on loyalty OCB (βLS (Future) → Loyalty OCB = 0.132, p < .05). Thus, H3a and H3b were supported. Lastly, a positive influence of current and future life satisfaction on restaurant employees’ intention to leave the industry was hypothesized (H4a and H4b). Participants’ current life satisfaction was found to have a significant negative influence on intentions to leave the restaurant industry (βLS (Current) → Leave = −0.303, p < .01). Thus, H4a was supported. However, participants’ future life satisfaction was found to increase their intentions to leave the industry (βLS(Future) → Leave = 0.167, p < .05), meaning that H4b was not supported.

4.4. The moderating effects of resilience and employment status

This study hypothesized that restaurant employees’ personality (i.e., resilience) and employment status (i.e., currently working vs. being furloughed) would moderate the relationship between current and anticipated life satisfaction and behavioral intentions (i.e., loyalty OCB and intentions to leave the restaurant industry). To find the moderating effect of the proposed variables, this study utilized a series of multi-group analyses.

Prior to examining the structural model, it was necessary to check the internal consistency of the resilience measurement. Cronbach’s α value was.920, confirming the internal consistency of resilience. The mean value of resilience was then calculated, and the sample was divided into two different groups based on the mean value (1: High resilience; 0: Low resilience). For the other grouping variable, this study utilized participants’ employment status (1: Currently working; 0: Furloughed). It was necessary to examine the measurement invariance across sub-samples (Hair et al., 2010). χ2 values of constrained and unconstrained models were compared. Results suggest that there was no difference in factor loadings between the groups (Δχ2 Resilience = 42.426, df = 29, p > .05; Δχ2 Employment Status = 28.685, p > .05). Thus, it was appropriate to proceed to multi-group analysis for the structural model.

A χ2 test was conducted to test whether any differences exist in the structural model between the sub-samples based on resilience and employment status. Specifically, χ2 was compared between the fully unconstrained and constrained models with paths from life satisfaction (i.e., current and future) to behavioral intentions (i.e., loyalty OCB and intentions to leave the restaurant industry). Δχ2 was marginally significant when comparing two subgroups based on resilience (Δχ2 = 13.394, p < .10), indicating that at least one path can be different based on the level of resilience.

A series of χ2 difference tests revealed that the impact of current life satisfaction on loyalty OCB was significantly different based on participants’ resilience ( Table 6). For those with high resilience, the influence of current life satisfaction on loyalty OCB was.434, while for participants with a lower level of resilience it was.766. Thus, H5a was supported. Also, Δχ2 was marginally significant for the paths between current life satisfaction and intentions to leave the restaurant industry (Δχ2 = 3.287, p < .10). More specifically, the influence of current life satisfaction on intentions to leave the industry was smaller for those with high resilience (βLS(Current) → Leave = −0.184, p < .05) compared to those with low resilience (βLS(Current) → Leave = −0.590, p < .01). Thus, H5c was supported. No other significant differences were found, implying that H5b and H5d were not supported. Lastly, χ2 difference was not significant when comparing the two groups based on employment status, meaning that H6a, H6b, H6c, and H6d were not supported by the results.

Table 6.

Moderating effects of resilience.

| Hypotheses | High Resilience |

Low Resilience |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t-value | β | t-value | Δχ2 | Results | ||||

| H5a: | LS_Current | → | Loyalty OCB | 0.434 | 5.722*** | 0.766 | 6.691*** | 9.481*** | Supported |

| H5b: | LS_Future | → | Loyalty OCB | 0.072 | 0.986 | -0.142 | -1.323 | 2.424 | Not supported |

| H5c: | LS_Current | → | Leave Industry | -0.184 | -2.341** | -0.59 | -4.439 | 3.287* | Supported |

| H5d: | LS_Future | → | Leave Industry | 0.088 | 1.103 | 0.424 | 3.198 | 1.692 | Not supported |

Note: ***p < .01, **p < .10

5. Discussion, implications, and future research

5.1. Discussion and implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has foisted unprecedented social, economic, and health-related challenges upon employees throughout the world. Particularly in the restaurant industry, employees have not only had to deal with a loss of job security, but also to adapt to a new working environment centered upon redesigned delivery methods, social distancing guidelines, and health and safety threats (Pesce, 2020). In addition to these challenges, neither employees nor the firms for which they work know when this situation will normalize. Hence, during such times of duress, it is important to understand the influence that individuals’ support systems, psychological capital, and employment status have on their life outlook and subsequent behavioral outcomes. This study, therefore, sought to examine the influence of perceived support (i.e., organizational support and social support) on life satisfaction (i.e., current and anticipated future life satisfaction), and then to analyze the influence of life satisfaction on employee’s loyalty OCB and intention to leave the restaurant industry. In addition, the moderating impact of resilience and employment status on the relationships between life satisfaction, loyalty OCB, and intentions to leave the restaurant industry were also examined.

The results of this study extend the organizational behavior literature with significant theoretical implications. The direct effects of social support (i.e., POS and PSS) were found to significantly and positively impact employee life satisfaction (i.e., current and anticipated), thus supporting the findings of Erdogan et al. (2012), Kim et al. (2004), and Uchino (2004). This study further revealed that employees’ perceptions of organizational and social support may play an important role in both their current and anticipated life satisfaction, thereby supporting prior findings on work-life spillover (Baranik et al., 2019, Uchino, 2004, Rhoades and Eisenberger, 2002), while also showing that home/life domains cannot be separated from each other, and that strength in one area will lead to strength in the other, supporting the work of Demerouti et al. (2005).

Another important finding of this study is the significant and positive effect of future life satisfaction on an employee’s intention to leave the restaurant industry. Most life satisfaction studies in the hospitality literature have not differentiated between current and future life satisfaction, mostly utilizing instruments that focus exclusively on respondents’ current life satisfaction. In contrast, this study implemented a temporal element, thereby extending our theoretical understanding of this construct. Given that this finding contradicts the current study’s initial hypothesis, there are various possible explanations.

For instance, the result may be due to the moderating impact that resilience has on the relationship between current life satisfaction and loyalty OCB, and current life satisfaction and intentions to leave the industry. Accordingly, individuals who have higher resilience illustrated an increased likelihood to leave the restaurant industry and decreased probability to exhibit loyalty OCB versus their low resilience counterparts. While numerous studies have found a positive relationship between resilience and behavioral outcomes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment (e.g., Hu et al., 2015; Hudgins, 2016; Paul et al., 2016), it is reasonable to suggest that high-resilience individuals also have the capability to adjust and adapt to a new job or work environment (Luthans et al., 2006). This suggestion supports prior research related to the job search self-efficacy literature, which suggests that individuals who believe they can find a different job are more likely to initiate voluntary job turnover (Moynihan et al., 2003). Furthermore, all the aforementioned findings should be viewed against the unprecedented backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, as these relationships have not previously been investigated in such an uncertain and high-stress environment.

Given these findings, this study suggests several practical implications. First, given that POS has a positive impact on life satisfaction, firms should seek to provide employees with both social and organizational support. While such support may be particularly helpful during stressful times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the restaurant industry is generally a high-stress work environment and such support should, therefore, not be limited only to these times. For example, Haas et al. (2020) state that employees have four types of need – hope, trust, compassion, and stability – which must be addressed through workplace practices that promote an adequate work-life fit. To achieve this, managers should be provided with training on how to support employees. Such training may include how to talk with employees about well-being and overcoming hurdles, setting realistic goals, praising good performance, treating employees with respect and dignity, and being a positive, encouraging, and supportive role-model. Other practical recommendations include the creation of support networks, the implementation of wellness programs and incentives, paid vacation time, volunteer days, on-site health and fitness events, and on- or off-site team-building group activities. Managers should also, as far as possible, match employees’ preferences with regard to their work schedules/shifts so that employees can fulfill their family and social obligations.

Second, restaurant firms should seek employee input when implementing new policies and procedures which, during the COVID-19 pandemic, include new safety measures, social distancing, and a shift to a delivery/curbside pickup and limited dine-in context. Restaurant employees often undergo stress due to their boundary spanning role of enforcing company policy as a frontline customer contact (Hight and Park, 2018). Thus, seeking their input about best practices for safety and efficiency can generate perceived trust by employees. In addition, firms that have had to lay off or furlough employees can provide mental health counseling and financial assistance, the latter including filing for unemployment benefits on behalf of their employees. Given that more than three million restaurant employees were either laid-off or furloughed during the pandemic (National Restaurant Association, 2020), helping with unemployment claims could ease delays in receiving benefits.

By incorporating the aforementioned suggestions and best practices, restaurant owners should benefit from employees’ increased life satisfaction, which should lead employees to adopt positive loyalty OCBs toward their restaurant companies and lower their desire to seek jobs in other industries.

5.2. Limitations and future research

Although this study provides significant theoretical and practical implications, it is not free of limitations. First, this investigation used cross-sectional data to analyze the research hypotheses. Despite using a robust theoretical background to develop the hypotheses, it is not possible to prove the existence of causal relationships among the constructs. Future investigations should use longitudinal studies to confirm the causality among constructs. Second, this research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas this was intentional, since this study aimed to examine the influence of support systems during the pandemic, future studies should investigate the relationships among constructs once the situation normalizes. Third, this research analyzed the influence of organizational support and social support on current and future life satisfaction. To further investigate the effects of a supportive work environment, future studies should analyze the role of co-workers, among other important company stakeholders. Fourth, this research examined loyalty OCB and intentions to leave the industry as life satisfaction outcomes. Future studies could investigate other attitudinal/emotional outcomes such as organizational commitment, employee motivation, and job satisfaction, among other constructs. Scholars should also explore the endogenous and exogenous factors that influence loyalty OCB and intentions to leave the industry. Finally, this investigation surveyed only restaurant employees in the United States. Future studies should extend to other hospitality sectors, such as accommodation, airlines, theme parks, tour operators, and other industries that were significantly impacted by the pandemic. It would also be interesting to apply this research to restaurant employees from other countries to compare the relationships across different cultures. By doing so, it would be possible to identify whether the employment status or resilience of employees can moderate the relationships differently in a workplace environment that is culturally different from the one investigated by the present research, thereby increasing the generalizability of the results.

References

- Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Assumptions and comparative strengths of the two-step approach: comment on Fornell and Yi. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992;20(3):321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino J.A., Russell D.W., Cutrona C.E., Altmaier E.M. Employment status, social support, and life satisfaction among the elderly. J. Couns. Psychol. 1996;43(4):480–489. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R.P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992;55(2):178–204. [Google Scholar]

- Baranik L.E., Cheung J.H., Sinclair R.R., Lance C.E. What happens when employees are furloughed? A resource loss perspective. J. Career Dev. 2019;46(4):381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Bartik, A.W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z.B., Glaeser, E.L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C.T. (2020). How are small businesses adjusting to COVID-19? Early evidence from a survey. Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020–42. Available at: 〈https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/BFI_WP_202042.pdf〉.

- Bellet, C., De Neve, J.-E., and Ward, G. (2019). Does employee happiness have an impact on productivity? Saïd Business School WP 2019–13. Available at 10.2139/ssrn.3470734 (Accessed 2 October 2020). [DOI]

- Bettencourt L.A., Gwinner K.P., Meuter M.L. A comparison of attitude, personality, and knowledge predictors of service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001;86(1):29–41. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienstock C.C., DeMoranville C.W., Smith R.K. Organizational citizenship behavior and service quality. J. Serv. Mark. 2003;17(4):357–378. [Google Scholar]

- Blau P. John Wiley; New York, NY: 1964. Exchanges and Power in Social Life. [Google Scholar]

- Borman W.C., Motowidlo S.J. In: Personnel Selection in Organizations. Schmitt N., Borman W.C., editors. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1993. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bufquin D., DiPietro R., Orlowski M., Partlow C. The influence of restaurant co-workers’ perceived warmth and competence on employees’ turnover intentions: the mediating role of job attitudes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017;60:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cain L., Busser J., Kang H.J. Executive chefs’ calling: effect on engagement, work-life balance and life satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018;30(5):2287–2307. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro C.B., Armario E.M., Ruiz D.M. The influence of employee organizational citizenship behavior on customer loyalty. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004;15(1):27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Daily updates of totals by week and state: Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 〈https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/index.htm〉.

- Chan S.H., Wan Y.K.P., Kuok O.M. Relationships among burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover of casino employees in Macau. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015;24:345–374. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.-T., Wang C.-H. Incivility, satisfaction and turnover intention of tourist hotel chefs: moderating effects of emotional intelligence. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019;31(5):2034–2053. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Johanson M.M. Organizational citizenship behavior and employee performance: a moderating effect of work status in restaurant employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008;32(3):307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Johanson M.M., Guchait P. Employees intent to leave: a comparison of determinants of intent to leave versus intent to stay. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009;28(3):374–381. [Google Scholar]

- Chow I.H., Lo T.W., Sha Z., Hong J. The impact of developmental experience, empowerment, and organizational support on catering service staff performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006;25(3):478–495. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979;16(1):64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R., Anthony E.L., Daniels S.R., Hall A.V. Social exchange theory: a critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017;11(1):479–516. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R., Mitchell M.S. Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005;31(6):874–900. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Bakker A.B., Schaufeli W.B. Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual-earner parents. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005;67(2):266–289. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E.D., Emmons R.A., Larsen R.J., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Inglehart R., Tay L. Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013;112(3):497–527. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth A.L., Quinn P.D., Seligman M.E.P. Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009;4:540–547. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R., Armeli S., Rexwinkel B., Lynch P.D., Rhoades L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001;86(1):42–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R., Fasolo P., Davis-LaMastro V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990;75(1):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R., Huntington R., Hutchison S., Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986;71(3):500–507. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R.M. Social exchange theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976;2(1):335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan B., Bauer T.N., Truxillo D.M., Mansfield L.R. Whistle while you work: a review of the life satisfaction literature. J. Manag. 2012;38(4):1038–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas A.J., Tetrick L.E. A three-wave longitudinal analysis of the causal ordering of satisfaction and commitment on turnover decisions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989;74(6):855–868. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A.I., Martinez L.F., Lamelas J.P., Rodrigues R.I. Mediation of job embeddedness and satisfaction in the relationship between task characteristics and turnover: a multilevel study in Portuguese hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017;29(1):248–267. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981;18(3):382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselli R.F., La Lopa J.M., Bai B. Job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intent: among food-service managers. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2001;42:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner A. The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960;25(2):161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz J.G., Marks N.F. Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: an ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000;5(1):111–126. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guchait P., Cho S., Meurs J.A. Psychological contracts perceived organizational and supervisor support: investigating the impact on intent to leave among hospitality employees in India. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2015;14(3):290–315. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, E.J., Nigam, J., Streit, J., Pandalai, S., Chosewood, L.C., & O’Connor, M. (2020) July 29. The role of organizational support and healthy work design. 〈https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2020/07/29/org_support_hwd/〉.

- Hair J.F., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. 7th ed. Pearson Education, Inc; 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hight S.K., Park J.-Y. Substance use for restaurant servers: causes and effects. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018;68:68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hight S.K., Park J.-Y. Role stress and alcohol use on restaurant server’s job satisfaction: which comes first? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019;76:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S., Lofy K.H., Wiesman J., Bruce H., Spitters C., Ericson K., Wilkerson S., Tural A., Diaz G., Cohn A., LeAnne Fox M.D., Patel A., Gerber S.I., Kim L., Tong S., Lu X., Lindstrom S., Pillai S.K. First case of 2019 novel Coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T., Zhang D., Wang J. A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015;76:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hudgins T.A. Resilience, job satisfaction and anticipated turnover in nurse leaders. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016;24(1):E62–E69. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M.D. Which is a better predictor of job performance: job satisfaction or life satisfaction? J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2006;8:20–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jung H.S., Yoon H.H. The impact of employees’ positive psychological capital on job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors in the hotel. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015;27(6):1135–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Kang J., Jang J. Fostering service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior through reducing role stressors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019;31(9):3567–3582. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M. Perceived organizational support, career satisfaction, and performance outcomes: a study of hotel employees in Cameroon. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012;24(5):735–752. [Google Scholar]

- Kenrick D.T., Funder D.C. Profiting from controversy. Am. Psychol. 1988;43(1):23–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., O’Neill J.W., Jeong S.-E. The relationship among leader-member exchange, perceived organizational support, and trust in hotel organizations. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2004;3(1):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtessis J.N., Eisenberger R., Ford M.T., Buffardi L.C., Stewart K.A., Adis C.S. Perceived organizational support a meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J. Manag. 2015:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-H., Hsiao C., Chen Y.-C. Linking positive psychological capital with customer value co-creation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017;29(4):1235–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans F. The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002;23(6):695–706. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans F., Vogelgesang G.R., Lester P.B. Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2006;5(1):25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S., King L., Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success. Psychol. Bull. 2005;131:803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Gillath O., Shaver P.R. Activation of the attachment system in adulthood: threat-related primes increase the accessibility of mental representations of attachment figures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002;83(4):881–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman R.H., Blakely G.L., Niehoff B.P. Does perceived organizational support mediate the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behavior? Acad. Manag. J. 1998;41:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan L.M., Roehling M.V., LePine M.A., Boswell W.R. A longitudinal study of the relationships among job search self-efficacy, job interviews, and employment outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2003;18(2):207–233. [Google Scholar]

- National Restaurant Association. (2020). 100,000 restaurants closed six months into pandemic. 〈https://restaurant.org/news/pressroom/press-releases/100000-restaurants-closed-six-months-into-pandemic〉.

- Nunnally J. McGraw-Hill; 1978. Psychometric Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Paul H., Bamel U.K., Garg P. Employee resilience and OCB: mediating effects of organizational commitment. Vikalpa: J. Decis. Mak. 2016;41(4):308–324. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W., Diener E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008;3(2):137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W., Diener E., Suh E. The temporal satisfaction with scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1998;70(2):340–354. [Google Scholar]

- Pesce, N.L. (2020, July 22). 55% of businesses closed on Yelp have shut down for good during the coronavirus pandemic. Market Watch. 〈https://www.marketwatch.com/story/41-of-businesses-listed-on-yelp-have-closed-for-good-during-the-pandemic-2020–06-25〉.

- Peterson C., Park N., Seligman M.E.P. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: the full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 2005;6(1):25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.-Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., Organ D.W. Self-Reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986;12(4):531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Ragland D.R., Ames G.M. Current developments in the study of stress and alcohol consumption. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20(s8):51a–53a. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restaurant Law Center (2020, April 24). Official orders closing or restricting foodservice establishments in response to COVID-19. 〈https://restaurant.org/downloads/pdfs/business/covid19-official-orders-closing-or-restricting.pdf〉.

- Rhoades L., Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002;87(4):698–714. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggle R.J., Edmondson D.R., Hansen J.D. A meta-analysis of the relationship between perceived organizational support and job outcomes: 20 years of research. J. Bus. Res. 2009;62:1027–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Salancik G.R., Pfeffer J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978;23(2):224–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T.E. Social ties and health: the benefits of social integration. Ann. Epidemiol. 1996;6(5):442–451. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy M.J., Efraty D., Siegel P., Lee D.J. A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theories. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001;55(3):241–302. [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti, I. (2020, July 2). 5 restaurant workers share their fears about going back to work. Vox. 〈https://www.vox.com/the-goods/21310143/coronavirus-safety-masks-restaurant-service-workers〉.

- Sontag, E. (2020, June 25). Where restaurants have reopened across the U.S. Eater. 〈https://www.eater.com/21264229/where-restaurants-reopened-across-the-u-s〉.

- Stamper C.L., Van Dyne L. Work status and organizational citizenship behavior: a filed study of restaurant employees. J. Organ. Behav. 2001;22:517–536. [Google Scholar]

- Steel P., Schmidt J., Shultz J. Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 2008;134(1):138–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart G., Barrick M. In: Personality and Organizations. Schneider B., Smith D., editors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. Four lessons learned from the person-situation debate: a review and research agenda; pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind A.M., Borchgrevink C.P., Kacmar K.M., Brymer R.A. Customer service employees’ behavioral intentions and attitudes: an examination of construct validity and a path model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2000;19(1):53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.-Y., Tsaur S.-H. Supervisory support climate and service-oriented organizational citizenship behavior in hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016;28(10):2331–2349. [Google Scholar]

- Teng C.C., Lu A.C.C., Huang Z.Y., Fang C.H. Ethical work climate, organizational identification, leader-member-exchange (LMX) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020;32(1):212–229. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah I.P., Zach F.J., Wang J. Do travelers trust intelligent service robots? Ann. Tour. Res. 2020;81:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. Yale University Press; 2004. Social Support and Physical Health: Understanding the Health Consequences of Relationships. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. Understanding the links between social support and physical health: a life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2009;4(3):236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne L., Graham J.W., Dienesch R.M. Organizational citizenship behavior: construct redefinition, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1994;37:765–802. [Google Scholar]

- Verquer M.L., Beehr T.A., Wagner S.H. A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003;63(3):473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Mann F., Lloyd-Evans B., Ma R., Johnson S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(156):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ma L., Zhang M. Transformational leadership and agency workers’ organizational commitment: the mediating effect of organizational justice and job characteristics. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2014;42(1):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yip J., Ehrhardt K., Black H., Walker D.O. Attachment theory at work: a review and directions for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2018;39(2):185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Guo Y., Newman A. Identity judgments, work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating effects based on group engagement model. Tour. Manag. 2017;61:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G.D., Dahlem N.W., Zimet S.G., Farley G.K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. [Google Scholar]