Abstract

Simple Summary

This is the first study providing important time-specific, age-specific, and reproduction-specific data for managing Spodoptera frugiperda infestations in maize crops using chlorantraniliprole. The application of chlorantraniliprole insecticide suppressed the population of S. frugiperda. The results revealed that fecundity was affected by chlorantraniliprole in the second filial generation, which suggests that the insecticide application during spring will prevent S. frugiperda infestation in maize crops during the autumn season.

Abstract

Fall armyworm [Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith, 1797)] was first reported in the Americas, then spread to all the continents of the world. Chemical insecticides are frequently employed in managing fall armyworms. These insecticides have various modes of actions and target sites to kill the insects. Chlorantraniliprole is a selective insecticide with a novel mode of action and is used against Lepidopteran, Coleopteran, Isopteran, and Dipteran pests. This study determined chlorantraniliprole’s lethal, sub-lethal, and trans-generational effects on two consecutive generations (F0, F1, and F2) of the fall armyworm. Bioassays revealed that chlorantraniliprole exhibited higher toxicity against fall armyworms with a LC50 of 2.781 mg/L after 48 h of exposure. Significant differences were noted in the biological parameters of fall armyworms in all generations. Sub-lethal concentrations of chlorantraniliprole showed prolonged larval and adult durations. The parameters related to the fitness cost in F0 and F1 generations showed non-significant differences. In contrast, the F2 generation showed lower fecundity at lethal (71 eggs/female) and sub-lethal (94 eggs/female) doses of chlorantraniliprole compared to the control (127.5–129.3 eggs/female). Age-stage specific survival rate (Sxj), life expectancy (Exj) and reproductive rate (Vxj) significantly differed among insecticide-treated groups in all generations compared to the control. A comparison of treated and untreated insects over generations indicated substantial differences in demographic parameters such as net reproduction rate (R0), intrinsic rate of increase (r), and mean generation time (T). Several biological and demographic parameters were shown to be negatively impacted by chlorantraniliprole. We conclude that chlorantraniliprole may be utilized to manage fall armyworms with lesser risks.

Keywords: Spodoptera frugiperda, chlorantraniliprole, demographic parameters, fitness costs, two-sex life table

1. Introduction

The fall armyworm [Spodoptera frugiperda (S. frugiperda hereafter)] is a devastating pest in most of the tropical and subtropical Americas [1,2]. In Africa, it has become a noxious agricultural pest [3,4]. Commonly affected crops by S. frugiperda include corn, rice, sugarcane, sorghum etc. [5,6]. It may have several broods yearly and covers great distances in a single night’s flight. The larvae of the pest eat the leaves, stalks, and flowers of cultivated plants [1,7]. The S. frugiperda populations are often controlled using chemical pesticides [8,9]. Different types of insecticides work in different ways to kill the target organisms [10]. Most pesticides are neurotoxic due to their effects on acetylcholine receptors (e.g., neonicotinoids), acetylcholine esterases (e.g., carbamates), or ion channel activity in nerve cell membranes (pyrethroids) [11]. Few insecticides act on chitin biosynthesis (benzoylurea, buprofezin), juvenile hormone (phenoxyphenoxy ether), or ecdysone to affect insect growth and molting (triazine). Other insecticides damage the midgut membrane or act on the mitochondrial respiratory electron transport chain (e.g., carbamates) (toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis) [11]. Different insecticides, such as emmamectin benzoate [12] and neem extracts [13], have been used to control S. frugiperda.

The baseline susceptibilities of deltamethrin, chlorantraniliprole, flubendiamide, thiodicarb, and chlorpyrifos have been determined against S. frugiperda [14]. Similarly, the baseline susceptibilities of different insecticides with control failure estimation for S. frugiperda were determined in Burkina Faso [15]. Entomopathogenic nematodes were used to control S. frugiperda in Thailand [16]. Insecticide ‘ampligo’ was used against S. frugiperda in the coastal Savannah agroecological zone of Ghana [17]. Different insecticides having field efficacy against S. frugiperda have been tested [18,19,20]. However, the lethal, sub-lethal and trans-generational effects of chlorantraniliprole on biological parameters, demographic traits, and fitness costs of S. frugiperda have been less explored in Pakistan.

Anthranilic diamides have a unique mode of action that activates the unregulated release of internal calcium storage channels, resulting in the depletion of calcium from an insect body, ultimately leading to paralysis and insect death [21]. Chlorantraniliprole belongs to anthranilic insecticides and is registered against Lepidopteran, Coleopteran, Dipteran, and Hemipteran insects [22,23]. Insecticides exert sub-lethal impacts on insects depending upon exposure time and dose [5,24,25]. Due to these sub-lethal impacts, insects experience minor effects on fecundity, reproduction, and development [26]. In addition to the lethal effects (direct killing), insecticides can also result in the degradation and chemical distribution in the field, negatively impacting insect physiology, behavior, reproduction, longevity and biology [23,27,28,29]. Chlorantraniliprole showed toxicity and field efficacy against S. frugiperda [30]. It also showed effective control against S. frugiperda when used through drip irrigation in China [31]. Chlorantraniliprole also provided effective control over the pest when used in combination with other pesticides/plant extracts [32]. Similarly, chlorantraniliprole showed toxicity in combination with carbaryl against S. frugiperda [33]. In the same way, chlorantraniliprole showed toxicity against S. frugiperda when combined with neem extract [34]. Different insecticides, including chlorantraniliprole showed sublethal effects on the development and reproduction of S. frugiperda [12].

Insect mortality, fertility, and lifespan may all be affected by environmental variables, including heat, pesticides, and secondary plant metabolites. Demographic toxicology, or the life table, is useful for assessing these impacts [35,36,37,38]. The conventional life table focused only on the female population and overlooked the male population. Furthermore, it does not consider data about individual variations and developmental phases [39]. Age-stage two-sex life tables eliminated the inherent inaccuracies present in life tables based on females by adding data from both sexes of a community into their calculations [40,41].

Understanding these population dynamics, which may assist explain distinct sub-lethal consequences on target insects, can be aided using the age-stage two-sex life table [42,43]. Knowing the population dynamics of certain insect species is important for the timely implementation of integrated pest control, two-sex tables with sub-lethal doses may serve this purpose [44,45].

Numerous studies implemented the two-sex life table for this purpose. For example, the development and reproduction of S. frugiperda were studied by Xie et al. [46] using an age-stage, two-sex life table to see how the effects of various hosts (maize and kidney bean) affected the organism. Guo et al. determined the larval performance and oviposition of S. frugiperda using two sex tables on three host plants [47]. The fitness and population life tables of S. frugiperda on solanaceous and oilseed crops have been determined in earlier studies [48,49]. Using a two-sex life table, sub-lethal effects of spinetroam against S. frugiperda growth and fecundity were determined [50]. Similarly, Iqbal et al. [51] used an age-stage, two-sex life table to investigate the impact that zinc oxide generated in the culture supernatant of B. thuringiensis had on the demographic characteristics of Musca domestica. Likewise, an age-stage, two-sex life table analysis was used to assess the predatory functional response and fitness characteristics of Orius strigicollis Poppius-fed Bemisia tabaci and Trialeurodes vaporariorum [52]. In the same way, ecotoxicological experiments were used to examine the sub-lethal effects of propargite on Amblyseius swirskii (Acari: Phytoseiidae) utilizing an age-stage, two-sex life table [53]. Various control measures for the management of arthropod pests are now being developed by researchers. These tactics are aimed to be less harmful to humans, the environment, and predators [54,55,56,57,58]. However, synthetic insecticides are still among the best options available.

The current study aimed to identify the lethal, sublethal, and transgenerational effects of chlorantraniliprole on S. frugiperda in Pakistan. Determining the lethal concentration and its impact on all larval instars of S. frugiperda survival will be helpful in understanding its chemical control in a better way. The impacts of sub-lethal concentrations on development, reproduction, and fecundity till two generations will help to overcome future resistance development in the maize cropping systems. A two-sex life table will help understand the control of S. frugiperda during its all larval, pupal, and adult exposure involving both the male and female sexes, which will further help control it under field conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Insect Collection

For laboratory studies, the insects were collected from the research fields of the University of Agriculture in Faisalabad, Pakistan (31°26′15.2″ N 73°04′37.9″ E) and were kept in cages. Insecticide-free maize leaves were given for colony preparation, and the adults were fed with a 10% honey solution. The studied species is an agricultural pest; therefore, no ethical permissions were required for the study.

2.2. Bioassay for Larvae

A bioassay study was conducted on newly hatched larvae using the leaf dip method. Maize leaves were cut into 6 cm discs and dipped in insecticide for 20 s. Chlorantraniliprole was added to distilled water according to the chosen concentrations. A preliminary test to find the dilution was conducted, and concentration was chosen accordingly. Leaves were dried after soaking and placed individually in Petri dishes. Each treatment was repeated three times, and mortality was observed after 48 h.

2.3. Lethal and Sub-Lethal Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on F0, F1 and F2 Generations

Lethal and sub-lethal concentrations were used in this experiment to observe mortality, survival, development duration (larva, pupa, and adult), fecundity, and reproductive parameters of S. frugiperda. Leaves were dipped in lethal concentration solutions (Table 1) of insecticide for 20 s. An untreated control was also included in the study for comparison. One larva was released in each Petri dish, and observations were taken after 48 h. Mortality was recorded, and surviving larvae were fed with fresh leaves of maize. For pairing the insects, pupae were taken to other dishes, differentiated during the pupal stage, and released pairwise in Petri dishes. Cotton soaked in a honey solution was placed inside the vial. The pairs were observed daily for their fecundity.

Table 1.

Toxicity of chlorantraniliprole on six larval instars of the F0, F1 and F2 generations of Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Generation | LC10 (mg/L) |

LC25 (mg/L) |

LC50 (mg/L) |

LC90 (mg/L) |

Slope ± SE | X2 | p-Value | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First instar | ||||||||

| F0 | 1.04 (0.86–1.16) |

1.21 (1.06–1.31) |

1.43 (1.32–1.51) |

1.96 (1.84–2.17) |

9.27 ± 1.05 | 33.16 | 2.07 | 16 |

| F1 | 0.33 (0.26–0.42) |

0.51 (0.41–0.61) |

0.81 (0.69–0.92) |

1.90 (1.68–2.19) |

3.44 ± 0.16 | 53.50 | 3.34 | 16 |

| F2 | 0.34 (0.26–0.41) |

0.52 (0.43–0.60) |

0.82 (0.72–0.93) |

1.99 (1.76–2.30) |

3.36 ± 0.14 | 58.60 | 3.66 | 16 |

| Second instar | ||||||||

| F0 | 1.10 (0.89–1.22) |

1.25 (1.08–1.34) |

1.44 (1.33–1.51) |

1.88 (1.76–2.15) |

11.02 ± 1.57 | 36.36 | 2.27 | 16 |

| F1 | 0.37 (0.27.46) |

0.54 (0.43–0.65) |

0.84 (0.71–0.96) |

1.92 (1.69–2.22) |

3.58 ± 0.17 | 59.27 | 3.70 | 16 |

| F2 | 0.36 (0.26–0.45) |

0.54 (0.42–0.64) |

0.83 (0.70–0.96) |

1.92 (1.69–2.23) |

3.54 ± 0.17 | 61.57 | 3.84 | 16 |

| Third instar | ||||||||

| F0 | 1.08 (0.85–1.30) |

1.55 (1.30–1.76) |

2.29 (2.06–2.50) |

4.83 (4.41–5.43) |

3.95 ± 0.25 | 40.88 | 2.55 | 16 |

| F1 | 0.99 (0.76–1.19) |

1.42 (1.18–1.63) |

2.13 (1.90–2.33) |

4.58 (4.20–5.12) |

3.86 ± 0.26 | 36.34 | 2.27 | 16 |

| F2 | 0.65 (0.51–0.78) |

1.06 (0.90–1.21) |

1.85 (1.66–2.03) |

5.23 (4.60–6.13) |

2.83 ± 0.12 | 54.21 | 3.38 | 16 |

| Fourth instar | ||||||||

| F0 | 0.88 (0.69–1.06) |

1.44 (1.22–1.63) |

2.47 (2.23–2.73) |

6.95 (5.94–8.53) |

2.86 ± 0.13 | 65.39 | 4.08 | 16 |

| F1 | 0.80 (0.62–0.96) |

1.33 (1.12–1.51) |

2.32 (2.08–2.56) |

6.73 (5.76–8.25) |

2.77 ± 0.12 | 63.76 | 3.98 | 16 |

| F2 | 0.81 (0.63–0.97) |

1.34 (1.14–1.52) |

2.35 (2.12–2.59) |

6.83 (5.85–8.35) |

2.76 ± 0.13 | 61.22 | 3.82 | 16 |

| Fifth instar | ||||||||

| F0 | 1.39 (1.23–1.53) |

1.97 (1.81–2.11) |

2.89 (2.75–3.03) |

6.02 (5.66–6.48) |

4.03 ± 0.25 | 14.38 | 0.89 | 16 |

| F1 | 1.49 (1.31–1.65) |

2.05 (1.88–2.21) |

2.93 (2.77–3.07) |

5.74 (5.40–6.18) |

4.38 ± 0.30 | 16.86 | 1.05 | 16 |

| F2 | 1.48 (1.27–1.66) |

2.05 (1.85–2.23) |

2.96 (2.79–3.12) |

5.94 (5.53–6.48) |

4.24 ± 0.30 | 20.33 | 1.27 | 16 |

| Sixth instar | ||||||||

| F0 | 1.41 (1.07–1.69) |

2.34 (2.02–2.60) |

4.11 (3.97–4.54) |

12.01 (9.49–17.26) |

2.75 ± 0.22 | 38.21 | 2.38 | 16 |

| F1 | 1.05 (0.82–1.27) |

2.00 (1.73–2.25) |

4.08 (3.65–4.64) |

15.77 (12.09–22.86) |

2.18 ± 0.12 | 47.73 | 2.98 | 16 |

| F2 | 1.31 (0.93–1.62) |

2.25 (1.885–2.54) |

4.10 (3.73–4.62) |

12.82 (9.75–20.07) |

2.59 ± 0.21 | 48.36 | 3.02 | 16 |

The values in parentheses present the range of the respective means; values are means ± SE (standard errors of the means).

2.4. Transgenerational Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on F1 and F2 Generations

Ninety (90) eggs were placed in an insect breeding chamber at 27 ± 1 °C and 75% relative humidity for each treatment to observe the transgenerational effects of chlorantraniliprole on the F1 and F2 generations of S. frugiperda. Upon hatching, one larva was placed in each Petri dish for observation and fed with insecticide-dipped leaves. The leaves were dipped in insecticide for 20 s, dried and provided to the larvae for feeding. Later, fresh leaves were changed every 24 h. The developmental period and survival rate of males and females were recorded.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Concentrations (LC10, LC25, LC50, and LC90) that caused 10%, 25%, 50%, and 90% mortality were calculated using POLO-Plus [59]. The data on mortality were examined using a one-way analysis of variance, and the mean differences were determined using Tukey’s HSD test in SAS software [60] at 95% probability. Using a two-sex table [42], and TWO-SEX MS CHART Program [61], we were able to assess many biological and fitness characteristics, as well as survival rate, adult lifespan, and age-specific fertility. Bootstrap analysis with a sample size of 10,000 was used to assess the means and standard errors of various life and biological parameters [62]. A confidence interval of difference was used to calculate the results of the bootstrap and paired bootstrap tests [63]. Age-stage specific survival rate (sxj), age-stage specific net reproductive value (vxj), and age-stage specific survival rate (exj) were determines according to Chi [42]. To create the graphs for the demographic factors, SigmaPlot version 12.0 was used.

The following equations were used to construct the age-stage component of the two-sex life table lx:

where k is the last stage of the study cohort.

Similarly, age-specific fecundity (mx) was calculated as follows:

According to Goodman’s recommendation, the Euler–Lotka equation was used to determine the intrinsic rate of rise [64].

The R0 (net reproductive rate), which is the total number of offspring that an individual can produce during the lifetime, was calculated as:

The relationship between R0 and mean female fecundity (F) was calculated as:

The N in the above equation represents the total number of individuals, while f presents the number of female adults in the study [65].

The finite rate (λ) was recorded as:

| λ = er |

The mean generation time (T) presents the time span that the population needs to increase R0 folds of its size. The value of T was calculated as follows:

Age-stage life expectancy (exj) was calculated as follows:

where siy is considered as probability, an individual of x and j will survive to age i and stage and calculated by the equation below:

Age-stage reproductive value is (Vxj) defined as the contribution of individuals of age x and stage j for the future population of insects. For age stage-specific, two-sex tables, the following equation is used [66] and calculated as follows:

3. Results

3.1. Toxicity of Chlorantraniliprole to F0, F1, and F2 Generations

The lowest (1.432 mg/L) and the highest LC50 (4.119 mg/L) value in F0 generation was recorded for the first and sixth instar larvae, respectively. Similarly, the lowest (0.810 mg/L) and the highest (4.080 mg/L) LC50 values of the F1 generation were noted for the first and sixth instar larvae, respectively. A similar trend for the LC50 value was noted for the F2 generation. The lowest (0.829 mg/L) and the highest (4.10 mg/L) LC50 value of the F2 generation was observed for the first and sixth instar larvae, respectively (Table 1).

The LC10 and LC25 values were determined from mortality concentration-response lines. The lowest (1.042 mg/L) and the highest (1.413 mg/L) LC10 value of the F0 generation was noted for the first and sixth instar larvae, respectively. Similarly, the first and sixth instar larvae of the F1 generation recorded the lowest (0.334 mg/L) and the highest (1.055 mg/L) LC10 values, respectively. Moreover, a similar trend in the LC10 value was observed of the F2 generation, where the first and sixth instar larvae had the lowest (0.345 mg/L) and the highest (1.315 mg/L) LC10 values, respectively (Table 1).

The lowest (1.212 mg/L) and the highest (2.345 mg/L) LC25 values of the F0 generation were noted in the first and sixth larval instars, respectively. Similarly, the first and sixth instar larvae of the F1 generation recorded the lowest (0.516 mg/L) and the highest (2.002 mg/L) LC25 values, respectively. A similar trend of LC25 values was noted for the F2 generation, where the lowest (0.52 mg/L) and the highest (2.25 mg/L) LC25 values were recorded for the first and sixth larval instars, respectively (Table 1).

The lowest (1.969 mg/L) and the highest (12.012 mg/L) LC90 values of the F0 generation were recorded for the first and sixth larval instars, respectively. Similarly, the first and sixth instar larvae of the F1 generation recorded the lowest (1.908 mg/L) and the highest (15.776 mg/L) LC90 values, respectively. A similar trend of LC90 values was noted for the F2 generation, where the lowest (1.99 mg/L) and the highest (12.82 mg/L) LC90 values were recorded for the first and sixth larval instars, respectively (Table 1).

3.2. Sub-Lethal and Transgenerational Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on Biological and Reproductive Parameters and of F0, F1 and F2 Generations

The LC10 and LC25 concentrations of chlorantraniliprole were used to observe biological and reproductive parameters on all instars and pupae in F0, F1, and F2 generations (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Sub-lethal (LC10, LC25) effects of chlorantraniliprole on biological traits of Spodoptera frugiperda for three generations.

| Conc. | Duration (Egg- Larva) (Days) |

1st Instar | 2nd Instar | 3rd Instar | 4th Instar | 5th Instar | 6th Instar | Pupa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0 | ||||||||

| Control | 2.80 ± 0.04 | 3.18 ± 0.04 | 1.26 ± 0.04 | 1.32 ± 0.04 | 1.26 ± 0.04 | 2.19 ± 0.04 | 3.12 ± 0.03 | 8.68 ± 0.06 |

| LC10 | 3.28 ± 0.04 | 3.42 ± 0.05 | 1.40 ± 0.05 | 1.51 ± 0.05 | 1.56 ± 0.05 | 2.53 ± 0.05 | 3.69 ± 0.04 | 9.57 ± 0.07 |

| LC25 | 3.65 ± 0.04 | 3.93 ± 0.02 | 1.92 ± 0.02 | 1.80 ± 0.04 | 1.82 ± 0.03 | 2.81 ± 0.04 | 3.93 ± 0.02 | 10.17 ± 0.07 |

| p-value | 0.21 | 0.000124 | 0.0152 | 0.088 | 0.0037 | 0.013 | 0.0009 | 0.243 |

| F | 6.40 | 8.92 | 4.43 | 9.75 | 2.78 | 1.85 | 4.42 | 1.39 |

| df | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| F1 | ||||||||

| Control | 2.68 ± 0.05 | 3.12 ± 0.03 | 1.23 ± 0.04 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 1.28 ± 0.04 | 2.27 ± 0.04 | 3.10 ± 0.03 | 8.65 ± 0.07 |

| LC10 | 3.45 ± 0.05 | 3.48 ± 0.05 | 1.38 ± 0.05 | 1.52 ± 0.05 | 1.40 ± 0.05 | 2.62 ± 0.05 | 3.70 ± 0.04 | 9.77 ± 0.08 |

| LC25 | 3.87 ± 0.03 | 3.95 ± 0.02 | 1.89 ± 0.03 | 1.86 ± 0.03 | 1.93 ± 0.02 | 2.86 ± 0.03 | 3.95 ± 0.02 | 9.94 ± 0.09 |

| p-value | 0.205 | 0.066 | 0.010 | 0.024 | 0.384 | 0.011 | 0.26 | 0.646 |

| F | 5.45 | 2.79 | 4.21 | 9.56 | 3.83 | 1.89 | 1.23 | 0.51 |

| df | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| F2 | ||||||||

| Control | 2.54 ± 0.05 | 3.07 ± 0.02 | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 1.36 ± 0.05 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 2.19 ± 0.04 | 3.07 ± 0.02 | 8.79 ± 0.06 |

| LC10 | 3.39 ± 0.05 | 3.22 ± 0.04 | 1.45 ± 0.05 | 1.50 ± 0.50 | 1.54 ± 0.05 | 2.62 ± 0.05 | 3.55 ± 0.05 | 9.65 ± 0.07 |

| LC25 | 3.76 ± 0.04 | 3.92 ± 0.02 | 1.93 ± 0.02 | 1.88 ± 0.03 | 1.90 ± 0.03 | 2.87 ± 0.03 | 3.93 ± 0.02 | 9.88 ± 0.08 |

| p-value | 0.65 | 0.123 | 0.989 | 0.94 | 0.007 | 0.068 | 0.20 | 0.130 |

| F | 0.63 | 0.28 | 4.25 | 10.70 | 2.48 | 3.14 | 1.93 | 0.36 |

| df | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

Values are means ± SE (standard errors of the means).

Table 3.

Sub-lethal (LC10, LC25) effects of chlorantraniliprole on reproductive parameters of Spodoptera frugiperda for 3 generations.

| Concentration | Pre-Oviposition Period (Days) |

Fecundity | Female Adult Longevity (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F0 | |||

| Control | 3.36 ± 0.065 | 394.53 ± 5.74 | 4.519 ± 0.067 |

| LC10 | 3.53 ± 0.068 | 341.73 ± 6.17 | 4.538 ± 0.068 |

| LC25 | 3.65 ± 0.065 | 337.15 ± 6.19 | 4.576 ± 0.067 |

| p-value | 0.523 | 0.991 | 0.368 |

| F | 0.955 | 1.738 | 0.412 |

| F1 | |||

| Control | 3.30 ± 0.063 | 368.71 ± 6.16 | 4.480 ± 0.067 |

| LC10 | 3.42 ± 0.067 | 343.38 ± 5.013 | 4.384 ± 0.066 |

| LC25 | 3.59 ± 0.067 | 346.76 ± 5.92 | 4.461 ± 0.068 |

| p-value | 0.0032 | 0.172 | 0.468 |

| F | 3.27 | 1.390 | 0.095 |

| F2 | |||

| Control | 3.28 ± 0.062 | 368.38 ± 5.535 | 4.384 ± 0.066 |

| LC10 | 3.44 ± 0.068 | 361.80 ± 5.799 | 4.423 ± 0.067 |

| LC25 | 3.69 ± 0.063 | 329.07 ± 5.177 | 4.403 ± 0.067 |

| p-value | 0.00040 | 0.284 | 0.943 |

| F | 3.61 | 0.295 | 1.894 |

Values are means ± SE (standard errors of the means).

Significant differences were noted among LC10 and LC25 concentrations and control treatment of the study. There was no significant difference in hatching duration of F0 (F = 6.40; df = 89; p = 0.214), F1 (F = 5.45; df = 89; p = 0.205) and F2 (F = 0.63; df = 89; p = 0.65) generations (Table 2). Significant difference was recorded for the first instar larval duration of F0 (F = 8.92; df = 89; p = 0.000124) generation, but not for the F1 (F = 2.79; df = 89; p = 0.066) generation. Similarly, F2 generation (F = 0.28; df = 89; p = 0.123) remained non-significant in this regard (Table 2). Significant differences were noted in 2nd instar larval duration of F0 (F = 4.43; df = 89; p = 0.0152) and F1 (F = 4.21; df = 89; p = 0.010) generations, whereas non-significant differences were noted for the F2 generation (F = 0.25; df = 89; p = 0.089) (Table 2). For 3rd instar larvae, non-significant differences were observed in larval duration of F0 (F = 9.75; df = 89; p = 0.088); however, in F1 (F = 9.56; df = 89; p = 0.024) generation significant difference was observed, while non-significant differences were noted for the F2 generation (F = 10.70; df = 89; p = 0.94) (Table 2).

The fourth instar larvae noted significant differences for larval duration in F0 (F = 2.78; df = 89; p = 0.0037), but non-significant for F1 (F = 3.83; df = 89; p = 0.384) and significant differences for the F2 generation (F = 2.48; df = 89; p = 0.007) (Table 2). Significant differences were observed in the larval duration of fifth instars belonging to the F0 (F = 1.85; df = 89; p = 0.013), F1 (F = 1.89; df = 89; p = 0.011) generations; however, non-significant differences were recorded for the F2 (F = 3.14; df = 89; p = 0.068) generation (Table 2). Similarly, significant differences were observed in the larval duration of sixth instars belonging to F0 (F = 4.42; df = 89; p = 0.0009), whereas those belonging to F1 (F = 1.23; df = 89; p = 0.26) and F2 (F = 1.93; df = 89; p = 0.20) generations remained non-significant (Table 2). For pupa duration, non-significant differences were noted in F0 (F = 1.39; df = 89; p = 0.243), F1 (F = 0.51; df = 89; p = 0.646) and F2 (F = 1.30; df = 89; p = 0.36) generations (Table 2).

Reproductive parameters of the F0, F1 and F2 generations are given in Table 3. Pre-oviposition for F0 had non-significant differences (F = 0.955; p = 0.523), while significant differences were noted for F1 (F = 3.27; p = 0.0032) and F2 (F = 3.61; p = 0.00040) generations. Fecundity for F0 (F = 1.738; p = 0.991), F1 (F = 1.390; p = 0.172) and F2 (F = 0.295; p = 0.284) observed non-significant differences. Female adult longevity for F0 (F = 0.412; p = 0.368), F1 (F = 0.095; p = 0.468) and F2 (F = 1.894; p = 0.943) remained non-significant (Table 3).

3.3. Effect of Chlorantraniliprole on Demographic Traits of F0, F1, and F2 Generations

Demographic characters calculated using two sex stage-specific life tables are shown in Table 4. For the F0 generation, the intrinsic rate of increase (r) was directly proportional to concentration which significantly decreased in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Table 4).

Table 4.

Transgenerational effects of chlorantraniliprole on demographic traits of Spodoptera frugiperda for the F0, F1, and F2 generations.

| F0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LC10 | Control | LC25 | |

| r | 0.172 ± 0.0036 ab | 0.194 ± 0.0040 a | 0.160 ± 0.0034 b |

| λ | 1.188 ± 0.0043 ab | 1.215 ± 0.0048 a | 1.174 ± 0.0039 b |

| R0 | 185.544 ± 18.16 b | 206.19 ± 21.006 a | 196.02 ± 18.074 b |

| T | 30.259 ± 0.26 a | 27.347 ± 0.184 b | 32.903 ± 0.375 a |

| GRR | 196.990 ± 18.24 b | 214.849 ± 21.13 a | 211.319 ± 18.43 b |

| F1 | |||

| r | 0.170 ± 0.0036 ab | 0.199 ± 0.0036 a | 0.157 ± 0.0029 ab |

| λ | 1.186 ± 0.0042 ab | 1.220 ± 0.0044 a | 1.170 ± 0.0034 ab |

| R0 | 182.322 ± 18.26 b | 213.33 ± 19.597 a | 196.122 ± 18.34 b |

| T | 30.472 ± 0.232 a | 26.866 ± 0.173 b | 33.564 ± 0.153 a |

| GRR | 198.209 ± 18.702 b | 220.959 ± 19.69 a | 215.759 ± 18.82 ab |

| F2 | |||

| r | 0.183 ± 0.0049 b | 0.211 ± 0.0062 a | 0.158 ± 0.0029 b |

| λ | 1.201 ± 0.0059 a | 1.235 ± 0.0077 a | 1.171 ± 0.0034 b |

| R0 | 213.77 ± 19.11 ab | 217.34 ± 19.35 a | 193.83 ± 17.30 b |

| T | 29.26 ± 0.599 a | 25.42 ± 0.601 b | 33.266 ± 0.265 a |

| GRR | 226.73 ± 19.48 ab | 229.19 ± 19.65 a | 201.04 ± 17.47 b |

Here, r—intrinsic rate of increase, λ—finite rate of increase, R0—net reproduction rate, T—mean length of a generation, GRR—gross reproduction rate; values are means ± SE (standard errors of the means).The means followed by different letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05)

The finite mean rate of increase (λ) was significantly different in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Table 4) and changed with increased concentration. The net reproductive rate (R0) was higher in control and decreased significantly with increased concentration in LC10 and LC25. The mean generation time (T) was prolonged in LC10, and LC25 treated insects compared to the control (Table 4). The GRR was significantly low in LC10 and LC25-treated insects compared to the control (Table 4).

For the F1 generation, r was directly proportional to concentration which significantly decreased in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Table 4). The λ was significantly different in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Table 4) and changed with increased concentration. The R0 was higher in control and decreased significantly with increased concentration in LC10 and LC25. The T was prolonged in the LC10 and LC25-treated insects compared to the control (Table 4). The GRR was significantly low in the LC10 and LC25-treated insects compared to the control (Table 4).

For the F2 generation, r was directly proportional to concentration which significantly decreased in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Table 4). The λ was significantly different in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Table 4) and changed with increased concentration. The R0 was higher in control and decreased significantly with increased concentration. The T was prolonged in LC10 and LC25-treated insects compared to the control (Table 4). The GRR was significantly low in LC10 and LC25-treated insects compared to the control (Table 4).

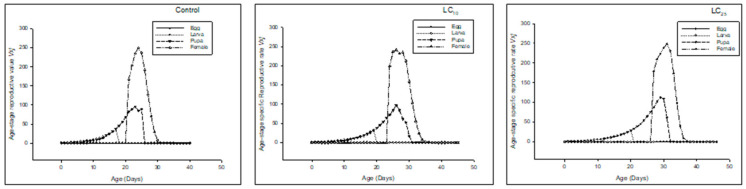

Age-stage specific survival rate (sxj) of the F0 generation denoted that the overall life span of the F0 (filial generation) prolonged in LC10 and LC25 as compared to the control (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age stage-specific survival rate (sxj) of the F0 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

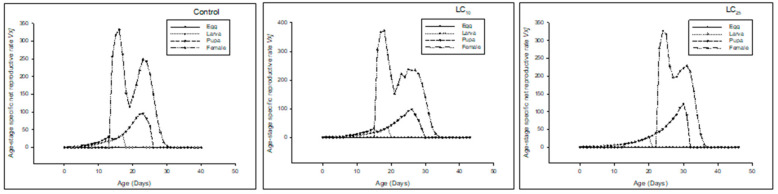

Age-stage-specific life expectancy(exj) was higher in LC10 and LC25-treated insects than in the control (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Age stage life expectancy (exj) of the F0 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

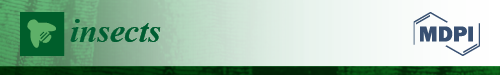

Age-stage specific reproductive rate (vxj) of the F0 generation denoted that the overall reproductive rate reduced in LC25-treated insects, and the LC10-treated insects also had less reproductive rate as compared to the control (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age stage reproductive value (vxj) of the F0 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

The sxj of F1 (first filial generation) denoted that the overall life span was prolonged in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Age stage-specific survival rate (sxj) of the F1 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

The exj was higher in LC10, and LC25-treated insects compared to the control (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Age stage life expectancy (exj) of the F1 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

The vxj of the F1 generation denoted that the overall reproductive rate was reduced in LC25-treated insects, and LC10-treated insects had less reproductive rate as compared to the control (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Age stage reproductive value (vxj) of the F1 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

The sxj of F2 (second filial generation) denoted that the overall life span was prolonged in LC10 and LC25 compared to the control (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Age stage-specific survival rate (sxj) of the F2 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

The exj was higher in LC10 and LC25-treated insects than in the control (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Age stage life expectancy (exj) of the F2 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

The vxj of the F2 generation denoted that the overall reproductive rate was reduced in LC25-treated insects, and LC10-treated insects had less reproductive rate as compared to the control (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Age stage-specific reproductive rate (vxj) of the F2 generation in Spodoptera frugiperda.

4. Discussion

By comprehending the life table of insects, effective management techniques may be created to control insects that are infesting agricultural plants. A greater understanding of the life cycle, survival rate, and reproduction may aid in managing insect pests [67,68]. In the context of muscle function, chlorantraniliprole is an anthranilic diamide that acts as a target for ryanodine receptors. After ingesting anthranilic pesticides, insects experience calcium loss, which leads to muscular contractions.

According to the current research findings, exposure to sublethal quantities of chlorantraniliprole led to a considerable reduction in both fecundity and fertility (egg hatch). On the other hand, Teixeira et al. [69] found that eating chlorantraniliprole at a concentration of 500 mg L−1 did not have a significant impact on the quantity of eggs deposited by apple maggot fly or the percentage of eggs that hatched. Knight and Flexner [70] similarly found that chlorantraniliprole had only a little impact on the adult C. pomonella population’s capacity to survive and reproduce. It is possible that the varying quantities of pesticides used cause variations between earlier and current findings, the various species of insects tested, and the technique used to apply the pesticides. Aside from that, the sublethal concentrations of chlorantraniliprole significantly extended the preoviposition of adults. This was in agreement with the observations made by Teixeira et al. [69], which stated that chlorantraniliprole-exposed insects begin egg-laying later than non-exposed adults do.

In accordance with the findings of Han et al. [71], who found that fecundity was dramatically decreased in LC10 and LC30-treated groups in comparison to the control group, our findings show that fecundity was severely reduced. Similar results were seen in our experiments, in which groups treated with LC10 and LC25 had a considerably lower fecundity than the control. Our findings are in further accord with Lutz et al. [72], who found that the lifespan of larvae and pupae was far longer than previously estimated. In the same way, the duration of the larval and pupal stages was lengthened in LC10- and LC25-treated groups compared to the control group in the present research. It’s possible that the disruption to the ryanodine receptors caused the patient to stop eating, which contributed to the protracted duration. Our findings are similarly in accordance with those of Ali et al. [5], who found that the development stages of the larval and pupal stages were severely altered in comparison to the control.

Compared to the control group, the length of time spent as a larva in the group of insects that had been treated with chlorantraniliprole for the present research was much longer. However, in our studies, pupal and adult emergence were not significantly altered in chlorantraniliprole-sprayed insects as compared to the control. Similar results have been reported for S. exigua where chlorantraniliprole decreased larval weight, pupal weight, and pupation rate. Nawaz et al. [73] reported that R0, r, and λ significantly decreased in chlorantraniliprole-treated groups compared to the control. Similar results for these parameters were recorded in the current study.

Similarly, Han et al. [71] observed a reduced survival rate and less fecundity in chlorantraniliprole-treated insects compared to control. Our study also recorded a lower survival rate and less fecundity in the chlorantraniliprole-treated insects compared to the control. Similar findings have also been reported by Wang et al. [74], where early-instar larvae of P. xylostella were affected more at 14 DAT when exposed to chlorantraniliprole-treated radish seedlings using the field rate. Long-lasting residual efficacy of chlorantraniliprole has also been observed against other pests like oblique banded leafroller [75], the grapevine moth and white grubs.

According to Han et al. [71], the values of R, r, and λ were considerably lower in chlorantraniliprole-treated groups compared to the control. These metrics showed a considerable drop in severity in the groups treated with chlorantraniliprole, which produced similar results as seen in the present investigation. According to Fernandes et al. [76], sublethal poisoning might affect an insect’s overall fitness and its reproductive capabilities. This notion was reinforced by the findings of the current study with P. xylostella. Yin et al. [77] reported quite similar findings to these, and observed that sublethal doses of Spinosad inhibited the population growth of P. xylostella by impairing the organism’s ability to survive, develop, and reproduce.

5. Conclusions

This is the first study that provides important basic time-specific, age-specific, and reproduction-specific data for understanding a S. frugiperda attack on maize with chlorantraniliprole. The impacts on their development and fecundity resulted in a decreased population of S. frugiperda. The results revealed that fecundity was mainly affected by chlorantraniliprole in the second filial generation, which suggests that chlorantraniliprole spraying in the spring season will save maize crops from S. frugiperda during the autumn, which is as the main attacking season of the fall armyworm.

Acknowledgments

This research work was funded by the Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (no. 2020B020223004); GDAS Special Project of Science and Technology Development (nos. 2020GDASYL-20200301003 and 2020GDASYL- 20200104025); Agricultural Scientific Research and Technology Promotion Project of Guangdong Province (no. 2021KJ260). King Khalid University supported this work through a grant KKU/RCAMS/22 under the Research Center for Advance Materials (RCAMS) at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.R.A., A.I. and K.Z.; Data curation, Z.R.A., A.A., K.Z. and S.A.; Formal analysis, Z.R.A., A.I., A.A. and K.Z.; Funding acquisition, J.L., A.I. and H.A.G.; Investigation, Z.R.A. and A.A.; Methodology, Z.R.A., A.I. and H.A.G.; Project administration, Z.R.A., A.I. and J.L.; Resources, I.U.H., Z.A.Q., S.A. and H.A.G.; Software, I.U.H., H.A.G., Y.N., M.B.T. and Z.A.Q.; Supervision, A.I. and J.L.; Validation, I.U.H., Y.N., M.B.T., M.A., Z.A.Q. and J.L.; Visualization, Y.N., M.B.T. and M.A.; Writing—original draft, Z.R.A. and A.I.; Writing—review and editing, A.I., A.A., K.Z., Z.A.Q., H.A.G. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data are within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research work was funded by the Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (no. 2020B020223004); GDAS Special Project of Science and Technology Development (nos. 2020GDASYL-20200301003 and 2020GDASYL- 20200104025); GDAS Action Capital Project to build a comprehensive industrial technology innovation center (no. 2022GDASZH-2022010106); Agricultural Scientific Research and Technology Promotion Project of Guangdong Province (no. 2021KJ260). King Khalid University supported this work through a grant KKU/RCAMS/22 under the Research Center for Advance Materials (RCAMS) at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Song X.-P., Liang Y.-J., Zhang X.-Q., Qin Z.-Q., Wei J.-J., Li Y.-R., Wu J.-M. Intrusion of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in Sugarcane and Its Control by Drone in China. Sugar Tech. 2020;22:734–737. doi: 10.1007/s12355-020-00799-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sparks A.N. A Review of the Biology of the Fall Armyworm. Fla. Entomol. 1979;62:82. doi: 10.2307/3494083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goergen G., Kumar P.L., Sankung S.B., Togola A., Tamò M. First Report of Outbreaks of the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a New Alien Invasive Pest in West and Central Africa. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0165632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva A.A., Alvarenga R., Moraes J.C., Alcantra E. Biologia de Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Em Algodoeiro de Fibra Colorida Tratado Com Silício. EntomoBrasilis. 2014;7:65–68. doi: 10.12741/ebrasilis.v7i1.365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali S., Li Y., Haq I.U., Abbas W., Shabbir M.Z., Khan M.M., Mamay M., Niaz Y., Farooq T., Skalicky M., et al. The Impact of Different Plant Extracts on Population Suppression of Helicoverpa armigera (Hub.) and Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum Mill) Yield under Field Conditions. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0260470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Zaimi S., Saranum M., Hudin L., Ali W. First Incidence of the Invasive Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith, 1797) Attacking Maize in Malaysia. BioInvasions Rec. 2021;10:81–90. doi: 10.3391/bir.2021.10.1.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boregas K.G.B., Mendes S.M., Waquil J.M., Fernandes G.W. Estádio de Adaptação de Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Em Hospedeiros Alternativos. Bragantia. 2013;72:61–70. doi: 10.1590/S0006-87052013000100009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sisay B., Tefera T., Wakgari M., Ayalew G., Mendesil E. The Efficacy of Selected Synthetic Insecticides and Botanicals against Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in Maize. Insects. 2019;10:45. doi: 10.3390/insects10020045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idrees A., Qadir Z.A., Afzal A., Ranran Q., Li J. Laboratory Efficacy of Selected Synthetic Insecticides against Second Instar Invasive Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Larvae. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0265265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casida J.E., Durkin K.A. Neuroactive Insecticides: Targets, Selectivity, Resistance, and Secondary Effects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:99–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casida J.E. Pest Toxicology: The Primary Mechanisms of Pesticide Action. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009;22:609–619. doi: 10.1021/tx8004949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H.-M., Feng H.-L., Wang G.-D., Zhang L.-L., Zulu L., Liu Y.-H., Zheng Y.-L., Rao Q. Sublethal Effects of Three Insecticides on Development and Reproduction of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Agronomy. 2022;12:1334. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12061334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tulashie S.K., Adjei F., Abraham J., Addo E. Potential of Neem Extracts as Natural Insecticide against Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021;4:100130. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2021.100130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulye M., Mehlhorn S., Boaventura D., Godley N., Venkatesh S., Rudrappa T., Charan T., Rathi D., Nauen R. Baseline Susceptibility of Spodoptera frugiperda Populations Collected in India towards Different Chemical Classes of Insecticides. Insects. 2021;12:758. doi: 10.3390/insects12080758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahissou B.R., Sawadogo W.M., Bokonon-Ganta A.H., Somda I., Kestemont M.-P., Verheggen F.J. Baseline Toxicity Data of Different Insecticides against the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Control Failure Likelihood Estimation in Burkina Faso. Afr. Entomol. 2021;29:435–444. doi: 10.4001/003.029.0435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajula J., Pittarate S., Suwannarach N., Kumla J., Ptaszynska A.A., Thungrabeab M., Mekchay S., Krutmuang P. Evaluation of Native Entomopathogenic Fungi for the Control of Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in Thailand: A Sustainable Way for Eco-Friendly Agriculture. J. Fungi. 2021;7:1073. doi: 10.3390/jof7121073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osae M.Y., Frimpong J.O., Sintim J.O., Offei B.K., Marri D., Ofori S.E.K. Evaluation of Different Rates of Ampligo Insecticide against Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith); Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Coastal Savannah Agroecological Zone of Ghana. Adv. Agric. 2022;2022:5059865. doi: 10.1155/2022/5059865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshmukh S., Pavithra H.B., Kalleshwaraswamy C.M., Shivanna B.K., Maruthi M.S., Mota-Sanchez D. Field Efficacy of Insecticides for Management of Invasive Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on Maize in India. Fla. Entomol. 2020;103:221. doi: 10.1653/024.103.0211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardke J.T., Temple J.H., Leonard B.R., Jackson R.E. Laboratory Toxicity and Field Efficacy of Selected Insecticides Against Fall Armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) 1. Fla. Entomol. 2011;94:272–278. doi: 10.1653/024.094.0221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adamczyk J.J., Leonard B.R., Graves J.B. Toxicity of Selected Insecticides to Fall Armyworms (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Laboratory Bioassay Studies. Fla. Entomol. 1999;82:230. doi: 10.2307/3496574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai T., Su J. Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on Development and Reproduction of Beet Armyworm, Spodoptera Exigua (Hübner) J. Pest Sci. 2011;84:381–386. doi: 10.1007/s10340-011-0366-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao G., Lu Q., Zhang L., Guo F., Liang G., Wu K., Wyckhuys K.A.G., Guo Y. Toxicity of Chlorantraniliprole to Cry1Ac-Susceptible and Resistant Strains of Helicoverpa Armigera. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2010;98:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2010.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Z.-K., Li X.-L., Tan X.-F., Yang M.-F., Idrees A., Liu J.-F., Song S.-J., Shen J. Sublethal Effects of Emamectin Benzoate on Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Agriculture. 2022;12:959. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12070959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh J.P., Marwaha K.K. Effect of Sublethal Concentrations of Some Insecticides on Growth and Development of Maize Stalk Borer, Chilo Partellus (Swinhoe) Larvae. Shashpa. 2000;7:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smagghe G., Tirry L. Biochemical Sites of Insecticide Action and Resistance. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2001. Insect Midgut as a Site for Insecticide Detoxification and Resistance; pp. 293–321. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cutler G.C. Insects, Insecticides and Hormesis: Evidence and Considerations for Study. Dose-Response. 2013;11:154–177. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.12-008.Cutler. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haynes K.F. Sublethal Effects of Neurotoxic Insecticides on Insect Behavior. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1988;33:149–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.33.010188.001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toscano L.C., Fernandes M.A., Rota M., Maruyama W.I., Andrade J.V. híBridos de Milho Frente Ao Ataque De Spodoptera frugiperda em Associação Com Adubação Silicatada E O Efeito Sobre O Predador Doru Luteipes. Rev. Agric. Neotrop. 2016;3:51–55. doi: 10.32404/rean.v3i1.680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teke M.A., Mutlu Ç. Insecticidal and Behavioral Effects of Some Plant Essential Oils against Sitophilus Granarius L. and Tribolium Castaneum (Herbst) J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021;128:109–119. doi: 10.1007/s41348-020-00377-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y., Ma Q., Tan Y., Zheng Q., Yan W., Yang S., Xu H., Zhang Z. The Toxicity and Field Efficacy of Chlorantraniliprole against Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Environ. Entomol. 2019;41:782–788. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X., Jiang H., Wu J., Zheng F., Xu K., Lin Y., Zhang Z., Xu H. Drip Application of Chlorantraniliprole Effectively Controls Invasive Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Its Distribution in Maize in China. Crop Prot. 2021;143:105474. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pes M.P., Melo A.A., Stacke R.S., Zanella R., Perini C.R., Silva F.M.A., Carús Guedes J.V. Translocation of Chlorantraniliprole and Cyantraniliprole Applied to Corn as Seed Treatment and Foliar Spraying to Control Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0229151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q., Rui C., Wang L., Huang W., Zhu J., Ji X., Yang Q., Liang P., Yuan H., Cui L. Comparative Toxicity and Joint Effects of Chlorantraniliprole and Carbaryl Against the Invasive Spodioptera Frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2022;115:1257–1267. doi: 10.1093/jee/toac059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altaf N., Arshad M., Majeed M.Z., Ullah M.I., Latif H., Zeeshan M., Yousuf G., Afzal M. Comparative Effectiveness of Chlorantraniliprole and Neem Leaf Extract against Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Sarhad J. Agric. 2022;38:833–840. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn J.J., Choi K.S. Population Parameters and Growth of Riptortus Pedestris (Fabricius) (Hemiptera: Alydidae) under Fluctuating temperature. Insects. 2022;13:113. doi: 10.3390/insects13020113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berber G., Birgücü A.K. Effects of Two Different Isolates of Entomopathogen Fungus, Beauveria Bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin on Myzus Persicae Sulzer (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Tarım Bilim. Derg. 2022;28:121–132. doi: 10.15832/ankutbd.828767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idrees A., Qadir Z.A., Akutse K.S., Afzal A., Hussain M., Islam W., Waqas M.S., Bamisile B.S., Li J. Effectiveness of Entomopathogenic Fungi on Immature Stages and Feeding Performance of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Larvae. Insects. 2021;12:1044. doi: 10.3390/insects12111044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Idrees A., Afzal A., Qadir Z.A., Li J. Bioassays of Beauveria Bassiana Isolates against the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Fungi. 2022;8:717. doi: 10.3390/jof8070717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Younas H., Razaq M., Farooq M.O., Saeed R. Host Plants of Phenacoccus Solenopsis (Tinsley) Affect Parasitism of Aenasius Bambawalei (Hayat) Phytoparasitica. 2022;50:669–681. doi: 10.1007/s12600-022-00980-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdel-Khalek A.A., Momen F.M. Biology and Life Table Parameters of Proprioseiopsis Lindquisti on Three Eriophyid Mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae: Eriophyidae) Persian J. Acarol. 2022;11:59–69. doi: 10.22073/pja.v11i1.68574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang Y.-B., Chi H. The Age-Stage, Two-Sex Life Table with an Offspring Sex Ratio Dependent on Female Age. J. Agric. 2011;60:337–345. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chi H. Life-Table Analysis Incorporating Both Sexes and Variable Development Rates among Individuals. Environ. Entomol. 1988;17:26–34. doi: 10.1093/ee/17.1.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng X.-M., Tao Y.-L., Chi H., Wan F.-H., Chu D. Adaptability of Small Brown Planthopper to Four Rice Cultivars Using Life Table and Population Projection Method. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42399. doi: 10.1038/srep42399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Planes L., Catalán J., Tena A., Porcuna J.L., Jacas J.A., Izquierdo J., Urbaneja A. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Spirotetramat on the Mealybug Destroyer, Cryptolaemus Montrouzieri. J. Pest Sci. 2013;86:321–327. doi: 10.1007/s10340-012-0440-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sunarto D.A. Peran Insektisida Botani Ekstrak Biji Mimba Untuk Konservasi Musuh Alami Dalam Pengelolaan Serangga Hama Kapas. J. Entomol. Indones. 2009;6:42. doi: 10.5994/jei.6.1.42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie W., Zhi J., Ye J., Zhou Y., Li C., Liang Y., Yue W., Li D., Zeng G., Hu C. Age-Stage, Two-Sex Life Table Analysis of Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Reared on Maize and Kidney Bean. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021;8:44. doi: 10.1186/s40538-021-00241-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo J., Zhang M., Gao Z., Wang D., He K., Wang Z. Comparison of Larval Performance and Oviposition Preference of Spodoptera frugiperda among Three Host Plants: Potential Risks to Potato and Tobacco Crops. Insect Sci. 2021;28:602–610. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu L., Zhou C., Long G., Yang X., Wei Z., Liao Y., Yang H., Hu C. Fitness of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda to Three Solanaceous Vegetables. J. Integr. Agric. 2021;20:755–763. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63476-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He L., Wu Q., Gao X., Wu K. Population Life Tables for the Invasive Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda Fed on Major Oil Crops Planted in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021;20:745–754. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63274-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao Z., Chen Y., He K., Guo J., Wang Z. Sublethal Effects of the Microbial-Derived Insecticide Spinetoram on the Growth and Fecundity of the Fall Armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2021;114:1582–1587. doi: 10.1093/jee/toab123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iqbal H., Fatima A., Khan H.A.A. ZnO nanoparticles produced in the culture supernatant of Bacillus thuringiensis ser. israelensis affect the demographic parameters of Musca domestica using the age-stage, two-sex life table. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022;78:1640–1648. doi: 10.1002/ps.6783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rehman S.U., Zhou X., Ali S., Rasheed M.A., Islam Y., Hafeez M., Sohail M.A., Khurram H. Predatory Functional Response and Fitness Parameters of Orius Strigicollis Poppius When Fed Bemisia Tabaci and Trialeurodes Vaporariorum as Determined by Age-Stage, Two-Sex Life Table. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9540. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alinejad M., Kheradmand K., Fathipour Y. Demographic Analysis of Sublethal Effects of Propargite on Amblyseius Swirskii (Acari: Phytoseiidae): Advantages of Using Age-Stage, Two Sex Life Table in Ecotoxicological Studies. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2020;25:906–917. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shahzad M.F., Idrees A., Afzal A., Iqbal J., Qadir Z.A., Khan A.A., Ullah A., Li J. RNAi-Mediated Silencing of Putative Halloween Gene Phantom Affects the Performance of Rice Striped Stem Borer, Chilo Suppressalis. Insects. 2022;13:731. doi: 10.3390/insects13080731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed K.S., Idrees A., Majeed M.Z., Majeed M.I., Shehzad M.Z., Ullah M.I., Afzal A., Li J. Synergized Toxicity of Promising Plant Extracts and Synthetic Chemicals against Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Pakistan. Agronomy. 2022;12:1289. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12061289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qadir Z.A., Idrees A., Mahmood R., Sarwar G., Bakar M.A., Ahmad S., Raza M.M., Li J. Effectiveness of Different Soft Acaricides against Honey Bee Ectoparasitic Mite Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) Insects. 2021;12:1032. doi: 10.3390/insects12111032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Idrees A. Protein Baits, Volatile Compounds And Irradiation Influence The Expression Profiles Of Odorantbinding Protein Genes in Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017;15:1883–1899. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1504_18831899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Idrees A., Qasim M., Ali H., Qadir Z.A., Idrees A., Bashir M.H., Qing J.E. Acaricidal Potential of Some Botanicals against the Stored Grain Mites, Rhizoglyphus tritici. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016;4:611–617. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robertson J.L., Jones M.M., Olguin E., Alberts B. Bioassays with Arthropods. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 60.SAS Institute Inc. SAS Software 9.4. TWOSEX-MSChart. SAS Inst. Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2014

- 61.Chi H. TWOSEX-MSChart: A Computer Program for the Age-Stage, Two-Sex Life Table Analysis. [(accessed on 1 September 2022)]. Version 2022.07.25. Available online: http://140.120.197.173/Ecology/prod02.htm.

- 62.Huang Y., Chi H. Age-stage, Two-sex Life Tables of Bactrocera Cucurbitae (Coquillett) (Diptera: Tephritidae) with a Discussion on the Problem of Applying Female Age-specific Life Tables to Insect Populations. Insect Sci. 2012;19:263–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2011.01424.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akkopru E.P., Atl han R., Okut H., Chi H. Demographic Assessment of Plant Cultivar Resistance to Insect Pests: A Case Study of the Dusky-Veined Walnut Aphid (Hemiptera: Callaphididae) on Five Walnut Cultivars. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015;108:378–387. doi: 10.1093/jee/tov011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goodman D. Optimal Life Histories, Optimal Notation, and the Value of Reproductive Value. Am. Nat. 1982;119:803–823. doi: 10.1086/283956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chi H., Getz W.M. Mass Rearing and Harvesting Based on an Age-Stage, Two-Sex Life Table: A Potato Tuberworm (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) Case Study. Environ. Entomol. 1988;17:18–25. doi: 10.1093/ee/17.1.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang Y., Li W., Xie W., Wu Q., Xu B., Wang S., Li C., Zhang Y. Development of Bradysia Odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae) as Affected by Humidity: An Age–Stage, Two-Sex, Life-Table Study. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2015;50:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s13355-014-0295-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harcourt D.G. The Development and Use of Life Tables in the Study of Natural Insect Populations. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1969;14:175–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.14.010169.001135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rozilawati H., Mohd Masri S., Tanaselvi K., Mohd Zahari T.H., Zairi J., Nazni W.A., Lee H.L. Life Table Characteristics of Malaysian Strain Aedes Albopictus (Skuse) Serangga. 2018;22:85–127. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teixeira L.A.F., Gut L.J., Wise J.C., Isaacs R. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on Three Species of Rhagoletis Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) Pest Manag. Sci. 2009;65:137–143. doi: 10.1002/ps.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knight A.L., Flexner L. Disruption of Mating in Codling Moth (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) by Chlorantranilipole, an Anthranilic Diamide Insecticide. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007;63:180–189. doi: 10.1002/ps.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han W., Zhang S., Shen F., Liu M., Ren C., Gao X. Residual Toxicity and Sublethal Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on Plutella Xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) Pest Manag. Sci. 2012;68:1184–1190. doi: 10.1002/ps.3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lutz A.L., Bertolaccini I., Scotta R.R., Curis M.C., Favaro M.A., Fernandez L.N., Sánchez D.E. Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on Spodoptera Cosmioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:2817–2821. doi: 10.1002/ps.5070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nawaz M., Cai W., Jing Z., Zhou X., Mabubu J.I., Hua H. Toxicity and Sublethal Effects of Chlorantraniliprole on the Development and Fecundity of a Non-Specific Predator, the Multicolored Asian Lady Beetle, Harmonia Axyridis (Pallas) Chemosphere. 2017;178:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang X., Li X., Shen A., Wu Y. Baseline Susceptibility of the Diamondback Moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) to Chlorantraniliprole in China. J. Econ. Entomol. 2010;103:843–848. doi: 10.1603/EC09367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sial A.A., Brunner J.F. Toxicity and Residual Efficacy of Chlorantraniliprole, Spinetoram, and Emamectin Benzoate to Obliquebanded Leafroller (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 2010;103:1277–1285. doi: 10.1603/EC09389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fernandes F.O., de Souza T.D., Sanches A.C., Dias N.P., Desiderio J.A., Polanczyk R.A. Sub-Lethal Effects of a Bt-Based Bioinsecticide on the Biological Conditioning of Anticarsia Gemmatalis. Ecotoxicology. 2021;30:2071–2082. doi: 10.1007/s10646-021-02476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yin X.H., Wu Q.J., Li X.F., Zhang Y.J., Xu B.Y. Sublethal Effects of Spinosad on Plutella Xylostella (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) Crop Prot. 2008;27:1385–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2008.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are within the manuscript.