Abstract

Background: The aim was to evaluate the feasibility of radiomics features based on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) at high b-values for grading bladder cancer and to compare the possible advantages of high-b-value DWI over the standard b-value DWI. Methods: Seventy-four participants with bladder cancer were included in this study. DWI sequences using a 3 T MRI with b-values of 1000, 1700, and 3000 s/mm2 were acquired, and the corresponding ADC maps were generated, followed with feature extraction. Patients were randomly divided into training and testing cohorts with a ratio of 8:2. The radiomics features acquired from the ADC1000, ADC1700, and ADC3000 maps were compared between low- and high-grade bladder cancers by using the Wilcox analysis, and only the radiomics features with significant differences were selected. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator method and a logistic regression were performed for the feature selection and establishing the radiomics model. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was conducted to assess the diagnostic performance of the radiomics models. Results: In the training cohorts, the AUCs of the ADC1000, ADC1700, and ADC3000 model for discriminating between low- from high-grade bladder cancer were 0.901, 0.920, and 0.901, respectively. In the testing cohorts, the AUCs of ADC1000, ADC1700, and ADC3000 were 0.582, 0.745, and 0.745, respectively. Conclusions: The radiomics features extracted from the ADC1700 maps could improve the diagnostic accuracy over those extracted from the conventional ADC1000 maps.

Keywords: bladder cancer, diffusion-weighted imaging, high b-value, radiomics nomogram, grading

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) ranks as the sixth most common cancer and the ninth leading cause of cancer-specific death in males worldwide [1]. In the prognosis and management strategy of BC, histologic grading has been recognized as a crucial factor to be considered [2]. BC is graded as low- or high-grade depending on the degree of nuclear anaplasia and architectural abnormalities [3]. Low-grade BC has demonstrated a lower rate of recurrence and stage progression compared to high-grade BC. The accurate assessment of the degree of BC tumor cell differentiation is essential not only for selecting the best treatment options, but also for sparing patients from unnecessary invasive treatment for low-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, reducing the likelihood of local recurrence and stage progression while maintaining the quality of life [4].

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) is considered a standard method to establish histologic grade [5,6]. However, inaccurate grading occurs in up to 15% of cases due to sampling errors and the heterogeneous characteristics of tumors [7,8]. Furthermore, due to the high cost and the need for repeat operations of TURBT [9], accurate and noninvasive techniques are needed to assess the aggressiveness of BC.

By using the diffusion of water molecules as a probe, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) can reveal tissue microstructural changes in vivo, particularly in cancer [10,11]. Among many quantitative parameters that DWI can produce, the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) has been investigated most extensively for characterizing cancerous tissues, including bladder cancer [12,13,14,15]. Its routine clinical use, however, has been hampered by the considerable overlap of ADC values among different tumor grades [16,17]. In clinical practice, ADC maps are typically calculated from DWI with b = 0 and 1000 s/mm2. The clinical application of high-b-value DWI is limited because of the inferior signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in 1.5 T or lower-field-strength MR systems. Recently, the popularization of the 3.0 T MR systems in medical units has enabled for us to acquire high-b-value DWI (e.g., b = 3000 s/mm2) with an acceptable SNR within a clinically acceptable data acquisition time frame. Recently, many studies have indicated that ADC maps obtained from high-b-value DWI are more effective than those obtained from standard-b-value DWI in several aspects [18,19,20].

Radiomics can extract a large number of advanced quantitative features from medical images and it has been used in the evaluation of tumor staging [21,22,23], grading [24], and predicting the recurrence of bladder cancer [25]. To the best of our knowledge, little research has been done to establish the application of radiomics nomogram based on high-b-value DWI in the preoperative evaluation of the grade of BC. Hence, this study aimed to explore the potential feasibility of radiomics nomogram based on DWI at high b-values (b = 1700 and 3000 s/mm2) for grading bladder cancer and to compare the possible advantage of high-b-value DWI over the standard-b-value (b = 1000 s/mm2) DWI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Characteristics

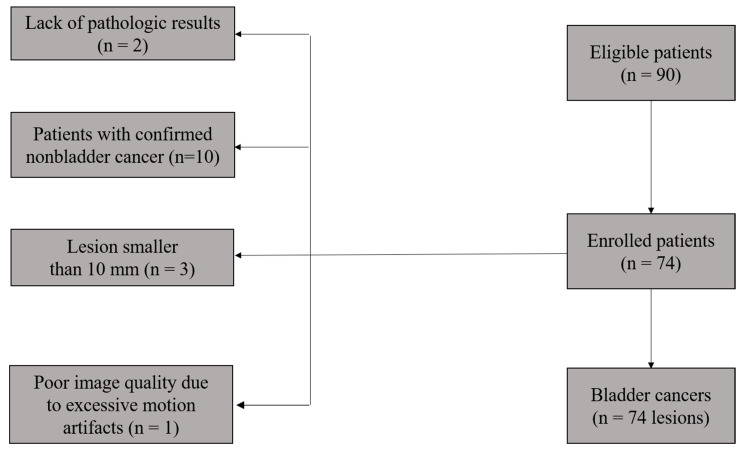

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital, and informed written consent was waived. Ninety patients with suspected or confirmed bladder lesions (e.g., by ultrasonography or CT) between July 2014 and November 2019 were enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria were (i) the availability of histopathological confirmation through TURBT or cystectomy and (ii) no treatment prior to the MR examination. The exclusion criteria consisted of (i) the unavailability of histopathological confirmation through TURBT or a cystectomy after the MRI examination (n = 2), (ii) confirmed nonbladder cancer (n = 10), (iii) poor image quality due to excessive motion artifacts (n = 1), or (iv) a diameter of tumor less than 1 cm (n = 3). With these criteria, a total of 74 patients (63 males, 11 females; median age, 61 ± 10 years; age range, 37–79 years) were finally included in this study. The flowchart of this study population is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study population.

2.2. Image Acquisition

All participants underwent MR examinations on a 3 T scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Brookfield, WI, USA) in the supine position with a 32-channel torso phased-array coil. The imaging protocol included axial fast spin-echo T1-weighted, axial fast recovery fast spin-echo T2-weighted, sagittal fast spin-echo T2-weighted, and diffusion-weighted imaging sequences. The acquisition parameters of each nondiffusion imaging sequence were as follows: (i) axial T1-weighted imaging: repetition time/echo time = 528/6.8 ms, field of view (FOV) = 340 × 340 mm2, matrix size = 320 × 256, and echo train length = 4; (ii) axial fast recovery T2-weighted imaging: repetition time/echo time = 3780/75 ms, FOV = 340 × 340 mm2, matrix size = 320 × 256, and echo train length = 16; (iii) sagittal T2-weighted imaging: repetition time/echo time = 5500/75 ms, FOV = 240 × 240 mm2, matrix size = 320 × 320, and echo train length = 24. In all sequences above, a section thickness of 4 mm with an intersection gap of 1 mm was used together with 2 averages. A series of axial diffusion-weighted images were obtained using a single-shot spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequence with 4 b-values, respectively: 01, 10004, 17006, and 30008 s/mm2, where the subscript denotes the number of averages. A Stejskal–Tanner diffusion gradient was applied along the three orthogonal directions in order to acquire trace-weighted images to eliminate the effects of diffusion anisotropy. The acquisition parameters for the DWI sequence were: repetition time/echo time = 2500/84 ms, FOV = 400 × 400 mm2, matrix size = 128 × 160, section thickness = 4 mm, and section gap = 1 mm.

2.3. Image Segmentation, Preprocessing, and Feature Extraction

For the patients with multifocal lesions, only the lesion with the largest diameter was accessed in this study. ITK-SNAP software (open source, www.itk-snap.org) was used for the manual segmentation. The volume of interest (VOI) covering the whole lesion was placed by delineating along the tumor border layer by layer on the DWI images (b = 1000 s/mm2) by one radiologist (Yanchun.Wang., with 6 years of experience in MRI diagnosis), and confirmed by another radiologist (Cui Feng, with 11 years of experience in MRI diagnosis).

The ADC was calculated by employing the monoexponential model. The signal attenuation S was produced with the following equation:

| (1) |

where S is the signal intensity at a given b-value and S0 is the signal intensity without diffusion weighting, b is known as the b-value, and D is the diffusion coefficient. The maps of ADC1000, ADC1700, and ADC3000 were obtained by employing equation (1) using diffusion-weighted images with two different b-values (b = 0 and 1000 s/mm2, b = 0 and 1700 s/mm2, b = 0 and 3000 s/mm2, respectively).

After the tumor segmentation, the texture analysis was conducted by using the LIFEx package [26] (version 6.00; Inserm, Orsay, France; https://www.lifexsoft.org (accessed on 13 May 2020)). Forty-nine texture features extracted from each VOI were as follows: seven statistical indexes (mean, minimum, maximum, the 25th percentile, the 50th percentile, the 75th percentile, and standard deviation of gray levels); six first-order histogram features (skewness, kurtosis, excess kurtosis, entropy_log10, entropy_log2, and energy); thirty-two higher-order features including the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), the neighborhood gray-level different matrix (NGLDM), the gray-level run-length matrix (GLRLM), and the gray-level zone-length matrix (GLZLM); and four shape indexes (sphericity, compacity, volume_mL, and volume_voxels) were extracted in this study. A detailed description of each texture feature is available in the technical appendix of LIFEx software [26].

Patients were randomly divided into training (80% of the total patients) and testing cohorts (20% of the total patients) using the “sample” function (with seed set as 120) in R software.

2.4. Feature Selection and Model Building

The feature selection was performed in the training cohort using the following 2-step procedures: (1) features with obvious significance in differentiating low- and high-grade bladder cancer were selected by performing a Wilcoxon analysis in which a significant level of p < 0.1 was set [27] and (2) the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method [28] was further applied to reduce the dimensionality of the features. An optimal LASSO penalty was acquired by minimizing the mean square error with a 10-fold cross-validation.

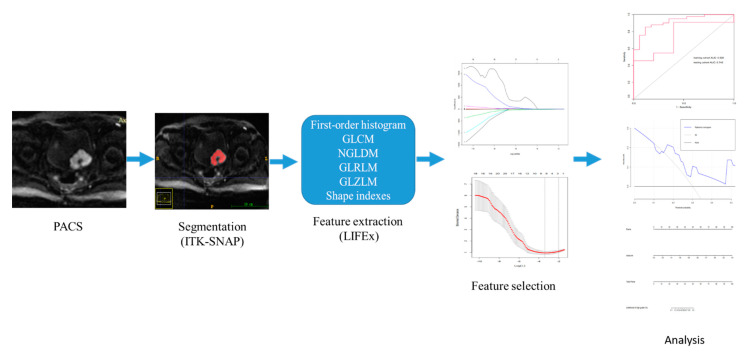

The best subset of features was then used to develop the radiomics models. Models for discriminating low- from high-grade bladder cancer were built by using a logistic regression. The performance of the built model was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic curve in the testing cohort. The radiomics workflow in this study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The radiomics workflow in this study.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The dimensionality reduction and model building processes of the radiomics features, including the intensity histogram, GLCM, and GLRLM of each model, were implemented in R (Version 3.6.0, https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 21 April 2021)).

The Wilcoxon analysis, LASSO regression, and ROC curve analyses were performed by means of the “caret” and “pROC” packages, respectively. In all tests of differences, a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics

The patients’ clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 74 patients, 27 underwent radical cystectomy, 4 partial cystectomy, and 43 TURBT. The pathological T stage was determined according to the 2017 TNM system [29], yielding 41, 20, 3, and 10 stages T1, T2, T3, and T4 patients, respectively. The tumors were classified as low-grade in 22 patients and high-grade in 52 patients according to the 2016 World Health Organization classification system [30]. The training cohort consisted of 58 patients (high grade, 41; low grade, 17) and the testing cohort consisted of 16 patients (high grade, 11; low grade, 5).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics.

| Variables | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Age (years) * | 61 ± 10 (37–79) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 63 (85) |

| Female | 11 (15) |

| No. of lesions | |

| Unifocal | 56 (76) |

| Multifocal | 18 (24) |

| Primary or recurrent tumors | |

| Primary | 72 (97) |

| Recurrent | 2 (3) |

| Tumor size (cm) * | 3.1 ± 1.6 (1.0–10.1) |

| Pathologic stage | |

| T1 | 41 (55) |

| T2 | 20 (27) |

| T3 | 3 (4) |

| T4 | 10 (16) |

| Histologic grade | |

| Low | 22 (30) |

| High | 52 (70) |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| Yes | 13 (18) |

| No | 61 (82) |

| Treatment methods | |

| TURBT | 43 (58) |

| Radical cystectomy | 27 (36) |

| Partial cystectomy | 4 (5) |

Note: Numbers in parentheses are percentages except where otherwise indicated. TURBT, transurethral resection of bladder tumor. * Numbers are means ± standard deviations, with ranges in parentheses.

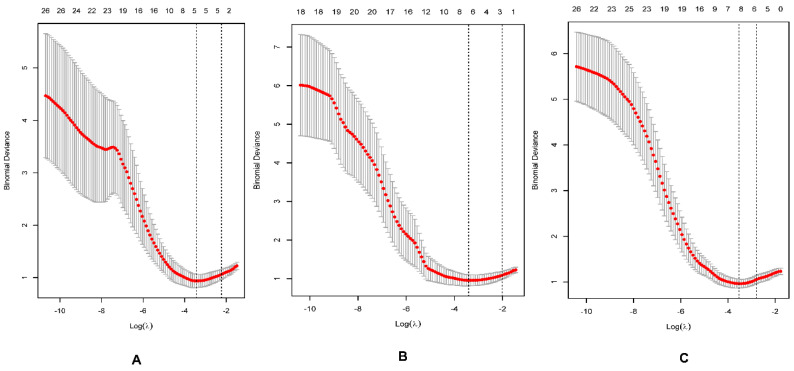

3.2. Feature Selection

In the training cohort, there were significant differences in 31, 26, and 44 features between the low and high grades of bladder cancer extracted from ADC1000, ADC1700, and ADC3000 maps, respectively. The best subset extracted from ADC1000, ADC1700, and ADC3000 maps by using the LASSO model consisted of five, seven, and seven features, respectively (Figure 3A–C and Table 2). The specific selected features included CONVENTIONAL_#std, CONVENTIONAL_#Q2, SHAPE_Sphericity (only for 3D ROI (nz > 1), GLRLM_RLNU, and NGLDM_Busyness for ADC1000; CONVENTIONAL_#std, SHAPE_Sphericity (only for 3D ROI (nz > 1), SHAPE_Compacity only for 3D ROI (nz > 1), GLRLM_HGRE, NGLDM_Busyness, GLZLM_HGZE and GLZLM_GLNU for ADC1700; HISTO_Skewness, SHAPE_Sphericity (only for 3D ROI (nz > 1), SHAPE_Compacity only for 3D ROI (nz > 1), GLCM_Correlation, GLRLM_LGRE, GLRLM_SRLGE, NGLDM_Contrast for ADC3000, respectively.

Figure 3.

The best subset extracted from the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression method model consisting of 5, 7, and 7 features, corresponding to b−values of 1000 (A), 1700 (B), and 3000 (C) s/mm2, respectively.

Table 2.

Calculation formula for radiomics signature.

| Rad-Score | Variables | Coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| ADC1000 | Intercept | 1.199576464 |

| CONVENTIONAL_#std | −0.582534519 | |

| CONVENTIONAL_#Q2 | −0.615993908 | |

| SHAPE_Sphericity (only for 3D ROI (nz > 1) | −0.77836837 | |

| GLRLM_RLNU | 0.340808516 | |

| NGLDM_Busyness | 0.029560922 | |

| ADC1700 | Intercept | 1.255336302 |

| CONVENTIONAL_#std | −0.54250182 | |

| SHAPE_Sphericity (only for 3D ROI (nz > 1) | −1.110704238 | |

| SHAPE_Compacity only for 3D ROI (nz > 1) | 0.36442195 | |

| GLRLM_HGRE | −0.538256985 | |

| NGLDM_Busyness | 0.050853414 | |

| GLZLM_HGZE | −0.10091227 | |

| GLZLM_GLNU | 0.004710521 | |

| ADC3000 | Intercept | 1.234603905 |

| HISTO_Skewness | 0.306892167 | |

| SHAPE_Sphericity (only for 3D ROI (nz > 1) | −0.918088191 | |

| SHAPE_Compacity only for 3D ROI (nz > 1) | 0.869977739 | |

| GLCM_Correlation | −0.62276962 | |

| GLRLM_LGRE | 0.139654102 | |

| GLRLM_SRLGE | −0.098482715 | |

| NGLDM_Contrast | −0.076828157 |

NOTE: GLRLM, the gray-level run-length matrix; NGLDM, the neighborhood gray-level different matrix; GLZLM, the gray-level zone-length matrix; GLCM, gray-level co-occurrence matrix.

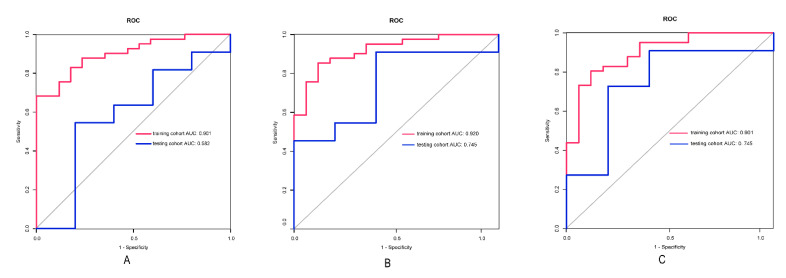

3.3. Performance of the Model

The three radiomics models achieved good performance in the training and testing cohorts. The AUCs of the ADC1000 model, ADC1700 model, and ADC3000 model were 0.901 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.825–0.977), 0.920 (95%CI: 0.849–0.990), and 0.901 (95%CI: 0.817–0.985) in the training cohorts. The AUCs of the ADC1000 model, ADC1700 model, and ADC3000 model were 0.582 (95% CI: 0.226–0.937), 0.745 (95%CI: 0.475–1.000), and 0.745 (95%CI: 0.451–1.000) in the testing cohorts. The detailed results are shown in Table 3. The ROC curves of the three models in the training and test models are shown in Figure 4.

Table 3.

Diagnostic performances of the DWI of three b-values interpretation in differentiating high- from low-grade bladder cancer in the training cohort and the test cohort.

| AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity | Specitivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training cohort (n = 58) | |||

| ADC1000 | 0.901 (0.825–0.977) | 0.683 | 1.000 |

| ADC1700 | 0.920 (0.849–0.990) | 0.854 | 0.882 |

| ADC3000 | 0.901 (0.817–0.985) | 0.805 | 0.882 |

| Test cohort (n = 16) | |||

| ADC1000 | 0.582 (0.226–0.937) | 0.548 | 0.800 |

| ADC1700 | 0.745 (0.475–1.000) | 0.909 | 0.600 |

| ADC3000 | 0.745 (0.451–1.000) | 0.727 | 0.800 |

Figure 4.

The ROC curve for the ADC1000 (A), ADC1700 (B) and ADC3000 (C) radiomics models for the training and testing cohorts.

4. Discussion

An accurate assessment of grade in BC is essential for urologists to develop appropriate strategies. Our results indicated that the radiomics features extracted from the ADC1700 maps could improve the diagnostic accuracy over that extracted from the conventional ADC1000 maps. We demonstrated the feasibility and possible superiority of using high-b-value DWI to assess the grade of bladder cancer.

Previous studies have reported the usefulness of texture analysis (TA) based on DWI to assess the grade of BC [24,31]. Razik et al. [31] indicated that a TA of DWI had excellent class separation capacity in differentiating high- from low-grade bladder cancer, which was consistent with our findings. However, the results of their article had an AUC maximum of 0.897 (b-value of 1500 s/mm2), which was higher than our AUC for a b-value of 1000 s/mm2, but lower than the AUC for a b-value of 1700 s/mm2, which also illustrated the advantages of high-b-values. Zhang et al. [24] indicated their maximum AUC value was 0.861 at a b-value of 1000 s/mm2, which was slightly lower than that of our study (AUC, 0.901). A possible reason for the discrepancy may be that more texture analysis parameters were extracted in our study, which was supposed to more accurately reflect the heterogeneity of bladder cancer in terms of the overall, local, and regional aspects [25]. It may also be because texture parameters were all extracted from the ADC maps in our study, while in the study of Zhang et al. [24], the texture parameters were extracted from the DWI and ADC maps.

Our result indicated that the radiomics parameters of ADC maps generated from high-b-value DWI (b = 1700 s/mm2 and 3000 s/mm2) provided a superior diagnostic performance compared with the standard b-value (b = 1000 s/mm2). Many previous studies have reported that DWI with a high b-value could enhance the clinical value in tumor grading and other aspects [18,19,20,32]. Kang et al. [18] indicated that the fifth percentile of the cumulative ADC histogram obtained at a high b-value (b = 3000 s/mm2) was the most promising parameter for differentiating high- from low-grade gliomas. Kwak et al. [18] indicated that the texture features extracted from high-b-value DWI images (b = 2000 s/mm2) produced better performance in the automated benign and malignant diagnosis of prostate lesions. These conclusions were similar to our findings. Intratumoral heterogeneity was an important consideration in tumor grading and predicting biological aggressiveness. Previous imaging studies on intratumoral heterogeneity were limited by the achievable voxel size. The advent of high-b-value DWI demonstrated a great potential for breaking this barrier and peeking into the voxels and was sensitive to tissue microstructures [11]. Therefore, ADC1700 and ADC 3000 were supposed to reflect the heterogeneity of the tumor grade better. However, the TA of ADC 3000 maps provided a less inferior diagnostic performance compared to that of ADC1700. The reason may be that the signal-to-noise (SNR) could be substantially reduced due to the increased diffusion-induced signal loss as well as the T2-induced signal attenuation caused by a longer TE to support the higher b-values.

It has to be declared that the diffusion-attenuated signal is described by the Stejskal–Tanner equation, assuming that the gradients are uniform. However, it has been indicated that the gradients are not uniform in almost any clinical or research MRI scanners, and the generalized Stejskal–Tanner equation has also been derived for nonuniform diffusion gradients [33]. It has been proven that the Stejskal–Tanner equation is still valid if the b-matrix can be calculated for each voxel separately, which is supposed to be achieved by using the b-matrix spatial distribution in DTI (BSD-DTI) technique [34,35].

This study has some limitations. First, the number of participants was moderate, and the distribution of pathologic grades was uneven with more high-grade than low-grade tumors. This may bias the statistical analysis and a further study of a larger population is required. Second, as a single-center retrospective study, the selective bias could not be avoided. Only one lesion was analyzed for the patients with multiple tumors, which could also cause a selection bias. Third, the small lesions (the diameter less than 1 cm) were not included due to the difficulty of drawing VOI, which led to the tumors evaluated in our study being relatively large. Fifth, systematic errors caused by the inhomogeneity of the gradients which affect the b-matrix, the eddy current effects, or other background interference do exit in the DWI measurements. However, the systematic errors are impossible to completely eliminate.

5. Conclusions

Our results indicated that the radiomics features extracted from ADC1700 maps could improve the diagnostic accuracy over those extracted from the conventional ADC1000 maps. We demonstrated the feasibility and possible superiority of using high-b-value DWI to assess the grade of bladder cancer, providing additional information for individualized treatment planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F. and Y.W.; methodology, C.F., Y.W., Z.Z. and Q.H.; software, Z.Z. and C.F.; validation, Z.Z. and Q.H.; formal analysis, C.F., Y.W. and X.M.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, Y.W. and Z.L.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, C.F. and Y.W.; visualization, X.M.; supervision, Y.W.; project administration, Y.W.; funding acquisition, Y.W. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective study was approved by our Institutional Ethics Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82102025, 82071889).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018, GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comperat E.M., Burger M., Gontero P., Mostafid A.H., Palou J., Roupret M., van Rhijn B.W.G., Shariat S.F., Sylvester R.J., Zigeuner R., et al. Grading of Urothelial Carcinoma and The New “World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs 2016”. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2019;5:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang G., McKenney J.K. Urinary Bladder Pathology: World Health Organization Classification and American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Update. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019;143:571–577. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0539-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan C.C., Chang Y.H., Chen K.K., Yu H.J., Sun C.H., Ho D.M. Prognostic significance of the 2004 WHO/ISUP classification for prediction of recurrence, progression, and cancer-specific mortality of non-muscle-invasive urothelial tumors of the urinary bladder: A clinicopathologic study of 1,515 cases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010;133:788–795. doi: 10.1309/AJCP12MRVVHTCKEJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babjuk M., Bohle A., Burger M., Capoun O., Cohen D., Comperat E.M., Hernandez V., Kaasinen E., Palou J., Roupret M., et al. EAU Guidelines on Non-Muscle-invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Update 2016. Eur. Urol. 2017;71:447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfred W.J., Lebret T., Comperat E.M., Cowan N.C., De Santis M., Bruins H.M., Hernandez V., Espinos E.L., Dunn J., Rouanne M., et al. Updated 2016 EAU Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017;71:462–475. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herr H.W., Donat S.M. Quality control in transurethral resection of bladder tumours. BJU Int. 2008;102:1242–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ark J.T., Keegan K.A., Barocas D.A., Morgan T.M., Resnick M.J., You C., Cookson M.S., Penson D.F., Davis R., Clark P.E., et al. Incidence and predictors of understaging in patients with clinical T1 urothelial carcinoma undergoing radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2014;113:894–899. doi: 10.1111/bju.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng C., Wang Y., Dan G., Zhong Z., Karaman M.M., Li Z., Hu D., Zhou X.J. Evaluation of a fractional-order calculus diffusion model and bi-parametric VI-RADS for staging and grading bladder urothelial carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 2022;32:890–900. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padhani A.R., Liu G., Koh D.M., Chenevert T.L., Thoeny H.C., Takahara T., Dzik-Jurasz A., Ross B.D., Van Cauteren M., Collins D., et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging as a cancer biomarker: Consensus and recommendations. Neoplasia. 2009;11:102–125. doi: 10.1593/neo.81328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang L., Zhou X.J. Diffusion MRI of cancer: From low to high b-values. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2019;49:23–40. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi S., Koga F., Kajino K., Yoshita S., Ishii C., Tanaka H., Saito K., Masuda H., Fujii Y., Yamada T., et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient value reflects invasive and proliferative potential of bladder cancer. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging. 2014;39:172–178. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi S., Koga F., Yoshida S., Masuda H., Ishii C., Tanaka H., Komai Y., Yokoyama M., Saito K., Fujii Y., et al. Diagnostic performance of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in bladder cancer: Potential utility of apparent diffusion coefficient values as a biomarker to predict clinical aggressiveness. Eur. Radiol. 2011;21:2178–2186. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abou-El-Ghar M.E., El-Assmy A., Refaie H.F., El-Diasty T. Bladder cancer: Diagnosis with diffusion-weighted MR imaging in patients with gross hematuria. Radiology. 2009;251:415–421. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2503080723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Shen Y., Hu X., Li Z., Feng C., Hu D., Kamel I.R. Application of R2* and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient in Estimating Tumor Grade and T Category of Bladder Cancer. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020;214:383–389. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avcu S., Koseoglu M.N., Ceylan K., Bulut M.D., Unal O. The value of diffusion-weighted MRI in the diagnosis of malignant and benign urinary bladder lesions. Br. J. Radiol. 2011;84:875–882. doi: 10.1259/bjr/30591350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin W.C., Chen J.H. Pitfalls and Limitations of Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Urinary Bladder Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2015;8:217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang Y., Choi S.H., Kim Y.J., Kim K.G., Sohn C.H., Kim J.H., Yun T.J., Chang K.H. Gliomas: Histogram analysis of apparent diffusion coefficient maps with standard- or high-b-value diffusion-weighted MR imaging--correlation with tumor grade. Radiology. 2011;261:882–890. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han C., Huang S., Guo J., Zhuang X., Han H. Use of a high b-value for diffusion weighted imaging of peritumoral regions to differentiate high-grade gliomas and solitary metastases. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging. 2015;42:80–86. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu H.H., Choi S.H., Ryoo I., Kim S.C., Yeom J.A., Shin H., Jung S.C., Lee A.L., Yoon T.J., Kim T.M., et al. Differentiation of true progression from pseudoprogression in glioblastoma treated with radiation therapy and concomitant temozolomide: Comparison study of standard and high-b-value diffusion-weighted imaging. Radiology. 2013;269:831–840. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H., Xu X., Zhang X., Liu Y., Ouyang L., Du P., Li S., Tian Q., Ling J., Guo Y., et al. Elaboration of a multisequence MRI-based radiomics signature for the preoperative prediction of the muscle-invasive status of bladder cancer: A double-center study. Eur. Radiol. 2020;30:4816–4827. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06796-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu X., Liu Y., Zhang X., Tian Q., Wu Y., Zhang G., Meng J., Yang Z., Lu H. Preoperative prediction of muscular invasiveness of bladder cancer with radiomic features on conventional MRI and its high-order derivative maps. Abdom. Radiol (NY). 2017;42:1896–1905. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X., Zhang X., Tian Q., Wang H., Cui L.B., Li S., Tang X., Li B., Dolz J., Ayed I.B., et al. Quantitative Identification of Nonmuscle-Invasive and Muscle-Invasive Bladder Carcinomas: A Multiparametric MRI Radiomics Analysis. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging. 2019;49:1489–1498. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X., Xu X., Tian Q., Li B., Wu Y., Yang Z., Liang Z., Liu Y., Cui G., Lu H. Radiomics assessment of bladder cancer grade using texture features from diffusion-weighted imaging. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging. 2017;46:1281–1288. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X., Wang H., Du P., Zhang F., Li S., Zhang Z., Yuan J., Liang Z., Zhang X., Guo Y., et al. A predictive nomogram for individualized recurrence stratification of bladder cancer using multiparametric MRI and clinical risk factors. J. Magn. Reason. Imaging. 2019;50:1893–1904. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nioche C., Orlhac F., Boughdad S., Reuzé S., Goya-Outi J., Robert C., Pellot-Barakat C., Soussan M., Frouin F., Buvat I. LIFEx: A freeware for radiomic feature calculation in multimodality imaging to accelerate advances in the characterization of tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 2018;78:4786–4789. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X., Liang D., Meng J., Zhou J., Chen Z., Huang S., Lu B., Qiu Y., Baker M.E., Ye Z., et al. Development and Validation of a Novel Computed-Tomography Enterography Radiomic Approach for Characterization of Intestinal Fibrosis in Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2303–2316. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Y.Q., Liang C.H., He L., Tian J., Liang C.S., Chen X., Ma Z.L., Liu Z.Y. Development and Validation of a Radiomics Nomogram for Preoperative Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2157–2164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paner G.P., Stadler W.M., Hansel D.E., Montironi R., Lin D.W., Amin M.B. Updates in the Eighth Edition of the Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging Classification for Urologic Cancers. Eur. Urol. 2018;73:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphrey P.A., Moch H., Cubilla A.L., Ulbright T.M., Reuter V.E. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur. Urol. 2016;70:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Razik A., Das C.J., Sharma R., Malla S., Sharma S., Seth A., Srivastava D.N. Utility of first order MRI-Texture analysis parameters in the prediction of histologic grade and muscle invasion in urinary bladder cancer: A preliminary study. Br. J. Radiol. 2021;94:20201114. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20201114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwak J.T., Xu S., Wood B.J., Turkbey B., Choyke P.L., Pinto P.A., Wang S., Summers R.M. Automated prostate cancer detection using T2-weighted and high-b-value diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Med. Phys. 2015;42:2368–2378. doi: 10.1118/1.4918318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borkowski K., Krzyżak A.T. The generalized Stejskal-Tanner equation for non-uniform magnetic field gradients. J. Magn. Reason. 2018;296:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krzyzak A.T., Klodowski K. The b matrix calculation using the anisotropic phantoms for DWI and DTI experiments; Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); Milan, Italy. 25–29 August 2015; pp. 418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borkowski K., Klodowski K., Figiel H., Krzyzak A.T. A theoretical validation of the B-matrix spatial distribution approach to diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reason. Imaging. 2017;36:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical concerns.