Abstract

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was adapted to measure immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgA classes of human serum antibody to Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Heat-stable antigen, a combination of C. jejuni serotype O:1,44 and O:53 in the ratio 1:1, was used as a coating antigen in the ELISA test. A total of 631 sera from 210 patients with verified Campylobacter enteritis were examined at various intervals after infection, and a control group of 164 sera were tested to determine the cut-off for negative results. With a 90th percentile of specificity, IgG, IgM, and IgA showed a sensitivity of 71, 60, and 80%, respectively. By combining all three antibody classes, the sensitivity was 92% within 35 days after infection, whereas within 90 days after infection, a combined sensitivity of 90% was found (IgG 68%, IgM 52%, and IgA 76%). At follow-up of the patients, IgG antibodies were elevated 4.5 months after infection but exhibited a large degree of variation in antibody decay profiles. IgA and IgM antibodies were elevated during the acute phase of infection (up to 2 months from onset of infection). The antibody response did not depend on Campylobacter species or C. jejuni serotype, with the important exception of response to C. jejuni O:19, the serotype most frequently associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome. All of the patients infected with this serotype had higher levels of both IgM (P = 0.006) and IgA (P = 0.06) compared with other C. jejuni and C. coli serotypes.

Together with Salmonella serovars, Campylobacter spp. are the most common bacterial enteric pathogens in developed countries, and Campylobacter jejuni is now the most recognized antecedent cause of Guillain-Barré syndrome (15, 16, 21). In Denmark, the incidence of registered Campylobacter infections has increased markedly since 1992 (from 22 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 1992 to 78 cases per 100,000 in 1999), and a similar emergence of Campylobacter has been observed in other industrialized countries (6). The diagnosis of Campylobacter infections is routinely done by stool culturing on selective medium, and C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli account for 94 and 6%, respectively, of Danish human isolates (17). Furthermore, culturing of stools is not a sensitive method for detection of the bacteria in patients treated with antibiotics or in patients with late reactive complications such as arthritis and Guillain-Barré syndrome or long-lasting intestinal distress (16). In these cases and for epidemiological studies in general, serodiagnosis is valuable. Antibodies to C. jejuni and C. coli can be detected in several test systems with various sensitivities using a homologous strain or selected reference strains in crude antigen preparations.

Agglutination and complement fixation (24, 25) and immunofluorescence (4) tests have been used for serological diagnosis of C. jejuni infection, but these have been limited by low sensitivity or specificity or the need to use homologous isolates. Few attempts on an experimental basis have been made for the development of enzyme immunoassays for detecting antibody response to C. jejuni (3, 9, 10, 22, 23). They all found that the quality of a diagnostic test relies mainly on the antigen preparation used.

The objective of the present study was to establish a sensitive and specific diagnostic serologic test for the demonstration of immunoglobulin class-specific antibodies common to the most prevalent strains of C. jejuni and C. coli in Denmark. Various preparations of antigens from different C. jejuni serotypes were tested in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Finally, a mixture of C. jejuni heat-stable antigens O:1,44 and O:53 (18) was found to be suitable for the diagnosis of Campylobacter infections in Denmark.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and serum samples.

The study included 210 stool culture-confirmed cases of Campylobacter infection from 1996 to 1997. All patients had gastroenteritis, were from general practice, and had a median age of 33.5 years (range, 10 to 76 years). Each person was asked to give a blood sample at approximately 3 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 2 years after onset of symptoms. All patients gave their written acceptance, and the Danish Central Scientific Ethical Committee approved the project. To determine the cut-off for a negative result, we included 162 negative sera from patients submitting blood samples for Helicobacter pylori serology testing. As control for cross-reactions, sera from patients found positive for H. pylori (n = 39), Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 (n = 39), Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis (n = 21), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (n = 9), S. enterica serovar Typhi (n = 5), S. enterica serovar Paratyphi B (n = 1), and S. enterica serovar Manhattan (n = 1), Legionella pneumophila (n = 21), and Escherichia coli O:157 (n = 4) were examined against the selected Campylobacter antigen. All antisera were supplemented with 0.01% sodium azide and stored at −20°C.

Identification and serotyping of isolates.

Fecal samples were cultured on CCDA substrate (18209 SSI Diagnostica, Hillerød, Denmark) and incubated in a microaerobic atmosphere (85% N2, 6% O2, 3% H2, and 6% CO2) at 37°C and examined after 2 to 3 days. All isolates were identified as C. jejuni or C. coli by conventional phenotypic tests (15). C. coli was distinguished from C. jejuni by a negative sodium hippurate test. Serotyping of C. jejuni and C. coli was undertaken by passive hemagglutination based on heat-stable antigens in microtiter plates against 47 C. jejuni and 19 C. coli antisera as previously described (17).

Preparation of heat-stable antigen.

A number of prevalent C. jejuni serotypes in Denmark (17) were considered candidates for the ELISA antigen, including C. jejuni O:1,44 (SSI:8133-96), O:2 (SSI:162-96), O:4 complex (SSI:36576-95), and O:53 (SSI:16059-96). In addition, C. jejuni O:19 (SSI:9075-96) was examined as candidate antigen. The bacteria were kept in bovine bouillon with 10% glycerol at −80°C until use. They were grown on 10% blood agar plates supplemented with 5% yeast (686 SSI Diagnostica) in an atmosphere of 90% N2, 5% O2, and 5% CO2 at 37°C for 2 days. All were harvested with saline, boiled for 1 h at 100°C, and stored at −20°C.

Following the ELISA procedure described below, 40 selected acute-phase sera from culture-confirmed Campylobacter patients and sera from 40 negative controls were used in the identification of the most appropriate antigen. The combination of C. jejuni O:1,44 and O:53 antigens gave the best result, exhibiting a difference between acute-phase sera from patients and controls larger than for a single antigen (results available on request). The combined heat-stable antigen had a protein concentration of 1 μg/ml, measured by the Pierce BCA protein assay (reagent 23225, 0194; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) in the ratio 1:1 between O:1,44 and O:53, and stored at −80°C.

ELISA procedure.

Polysorb microwell plates (17106; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated overnight at 5°C with 100 μl of a solution of the described antigen in coating buffer (0.1 M sodium carbonate [pH 9.6]) with a total protein concentration of 1 μg/ml. Plates were emptied and incubated for 15 min with blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] [pH 7.4] with 5% Tween 20) and washed four times with PBS [pH 7.4] containing 0.1% Tween 20.

All test sera were diluted 1:400 in PBS containing 0.01% (wt/vol) sodium azide. Test and control sera were applied in duplicate for 75 min at room temperature, followed by four cycles of washing. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled rabbit antiserum to human IgG (Dako 216; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), IgM (Dako 215; Dako), or IgA (Dako 214; Dako) was diluted 1:2,000, 1:1,000, and 1:500, respectively, in washing buffer, and 100 μl was added to each well, followed by another incubation for 75 min at room temperature before washing. Finally, 100 μl of tetramethylene benzidine (4380A; Kem-En-Tec, Copenhagen, Denmark) substrate was added and incubated for 10 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 0.2 M H2SO4. The optical density (OD) was read as arbitrary units (a.u.) at 450 nm, with background correction at 620 nm.

Selection of reference sera.

To identify suitable control sera, 40 sera from patients positive for Campylobacter antibodies and 164 sera from patients negative for H. pylori antibodies were measured against the heat-stable combination antigen. Sera from patients positive for Campylobacter antibodies with OD values between 1.2 and 2.2 a.u. were pooled and used as a positive control. Sera from patients found negative for H. pylori with OD values for Campylobacter antibodies below 0.25 a.u. were pooled and used as a negative control.

Calibration system.

In order to control day-to-day variation, a positive control serum diluted 1:200, 1:400, 1:600, 1:800, and 1:1,200 was included in duplicate on each plate along with three blind wells. The mean value of the blind wells was subtracted from all values, and the curve was evaluated by linear regression analysis; the test was approved only if the correlation coefficient was above 0.95. The mean ODs of the reference sera diluted 1:400, 1:600, and 1:800 in 10 assays performed over 10 days were: IgG, 2.353, 2.184, and 1.960 a.u.; IgM, 1.454, 1.087, and 0.816 a.u.; and IgA, 1.421, 0.993, and 0.702 a.u., respectively. The ODs of the positive controls were adjusted in each experiment to fit the mean slope of the titration curve for the reference sera, and the values of the test sera were adjusted by the same relation.

Statistical methods.

The mean antibody response following Campylobacter infection was modeled in a generalized linear mixed model tailored for the analysis of unbalanced repeated measurements, i.e., longitudinal data with variable time of follow-up and variable intervals between measurements (7). Based on an evaluation of model fit, we decided to model square-root-transformed ODs by a separate piecewise linear function with knots at 4.5 months after infection for IgG, 2 months for IgM, and 2.5 months as well as 7 months for IgA. Time since infection, Campylobacter species, C. jejuni serotype, and age were used as explanatory variables. To account for individual variability, we used a random-effect model, supposing that the antibody response depends on some common level of antibodies and supposing that a linear time trend exists for each person but with a varying interpersonal random intercept. Maximum-likelihood methods were used for the regression analyses by applying the MIXED procedure of the SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), and hypothesis testing was done by likelihood ratio tests.

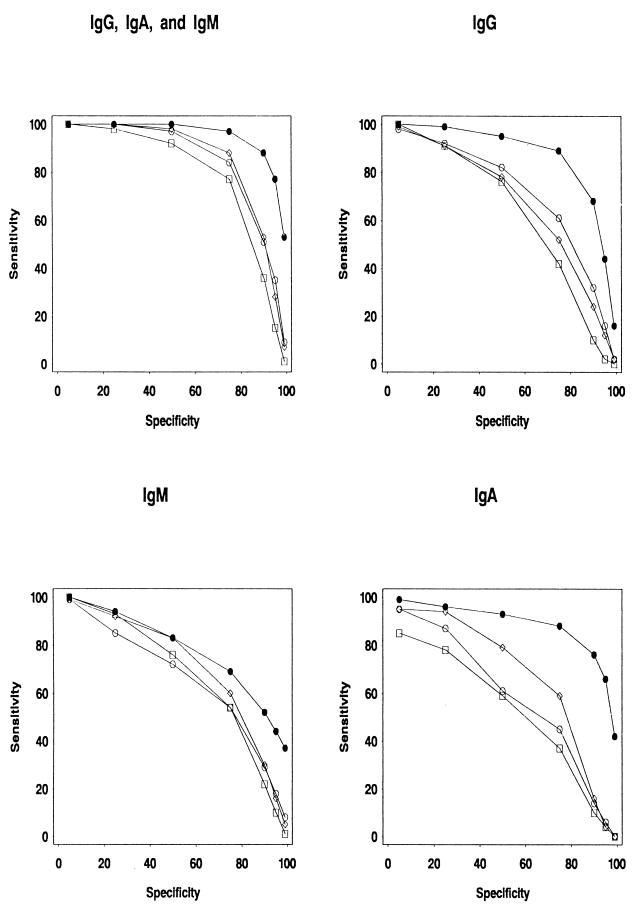

Different OD values corresponding to the 0.05, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 0.90, and 0.95 fractiles were evaluated as potential lower cut-off values for positive results. At each different OD value, sensitivity was defined as the percentage of samples in the true positive group that gave a value greater than the cut-off value. The paired sensitivity and specificity, i.e., fractiles for cut-off, estimates were graphically shown in a receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve (20).

RESULTS

Identification and serotyping of isolates.

From the 210 patients included in the study, a total of 180 Campylobacter isolates were available for further analysis; 173 (96%) were C. jejuni and 7 (4%) were C. coli. The distribution of serotypes is shown in Table 1. Most isolates reacted in only one serum or in a combination of sera comprising well-known complexes, e.g., O:1,44, O:4 complex, and O:6,7. Four C. jejuni isolates reacted with two or more antisera, which were not within well-known complexes but were O:2,38, O:3(13,50,65), O:10,44, and O:13,65, as did one of the C. coli, O:24,47. The most common C. jejuni serotypes were O:2, O:4 complex, and O:1,44, accounting for 49% of the cases, whereas the other serotypes each represented 4.2% or less.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of serotypes isolated from patients during this investigation

| Serotypea | No. of samples | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni | ||

| 1,44 | 20 | 11.6 |

| 2 | 34 | 19.7 |

| 4 complexb | 28 | 16.2 |

| 19 | 5 | 2.9 |

| 53 | 3 | 1.7 |

| 1 | 3 | 1.7 |

| 2,38 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 7 | 4.0 |

| 3 (13,50,65) | 2 | 1.2 |

| 5 | 6 | 3.5 |

| 6,7 | 7 | 4.0 |

| 9 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 10 | 4 | 2.3 |

| 10,44 | 2 | 1.2 |

| 11 | 3 | 1.7 |

| 12 | 7 | 4.0 |

| 13 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 13,65 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 15 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 17 | 2 | 1.2 |

| 18 | 3 | 1.7 |

| 21 | 5 | 2.9 |

| 23,36 | 2 | 1.2 |

| 27 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 31 | 2 | 1.2 |

| 33 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 35 | 2 | 1.2 |

| 37 | 3 | 1.7 |

| 42 | 1 | 0.6 |

| 44 | 4 | 2.3 |

| 57 | 4 | 2.3 |

| NT | 4 | 2.3 |

| UK | 3 | 1.7 |

| Total | 173 | 100.0 |

| C. coli | ||

| 24,47 | 1 | 14 |

| 30 | 1 | 14 |

| 46 | 3 | 44 |

| 47 | 1 | 14 |

| 54 | 1 | 14 |

| Total | 7 | 100 |

NT, not typeable; UK, unknown.

Serotypes 4, 13, 16, 43, 50, and others.

Antibody response by ELISA.

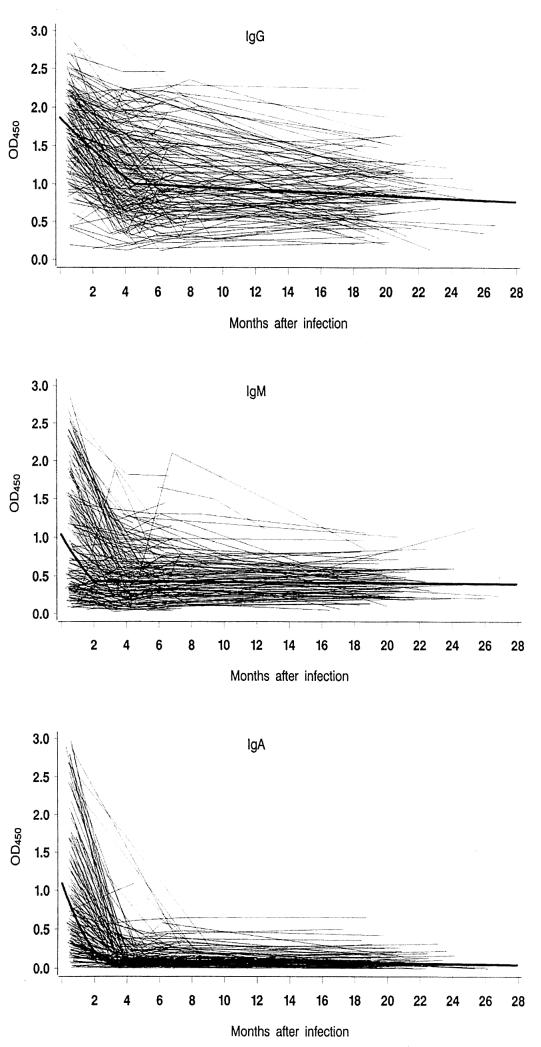

In the 164 negative control sera, IgG antibody values ranged from 0.08 to 2.43 a.u. (median, 0.73 a.u.), IgM ranged from 0.004 to 1.33 a.u. (median, 0.29 a.u.), and IgA ranged from 0.002 to 0.95 a.u. (median, 0.10 a.u.). The 90th percentile for IgG, IgM, and IgA was 1.49, 0.56, and 0.22 a.u., respectively. A total of 631 measurements were taken among the 210 patients; Fig. 1 shows the antibody response profiles at follow-up as well as the fitted population average for each immunoglobulin class.

FIG. 1.

Serum antibody response to Campylobacter infection in patients. (A) IgG; (B) IgM; (C) IgA. Individual responses of 210 patients over a 2-year period according to immunoglobulin class and the fitted population average (bold line) are shown.

IgG antibody values (Fig. 1A) decreased from the acute phase of infection up to 4.5 months after infection. The mean value continued to decrease in the follow-up period but very slowly around an OD of 1.0 a.u., i.e., between the 75th and 90th percentiles of negative sera. However, the curves exhibited a very large individual variation between patients, and some individuals had high values throughout the follow-up period, whereas others remained at low levels. There was no significant effect of age for this immunoglobulin class.

In Fig. 1B, the IgM antibody values, which were raised in the first 2 months following infection, are shown. At follow-up more than 2 months after the infectious event, the mean response remained stable at about 0.4 a.u. The IgM response was highest among the youngest patients and decreased with increasing age of infection (P = 0.0001). Thus, compared with patients older than 45 years, individuals in the age range from 10 to 25 years had 0.08 a.u. (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.04 to 0.13), 26 to 35 years had 0.04 a.u. (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.08), and 36 to 45 years had 0.03 a.u. (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.08) higher values. The proportion of patients with an IgM value above cut-off at first sampling by age group is presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Number of IgM-positive samples at first examination according to patient's age, determined 8 to 72 days after infectiona

| Age (yr) | No. of samples tested | No. (%) positive |

|---|---|---|

| 10–25 | 59 | 47 (79.7) |

| 26–35 | 57 | 41 (71.9) |

| 36–45 | 36 | 23 (63.9) |

| ≥46 | 58 | 12 (20.7) |

Chi squared for linear trend in proportions, 42.58; P > 0.001.

In Fig. 1C, the IgA antibody response, which declined rapidly from the acute phase to 2.5 months following infection, is shown. At later follow-up, the values were almost uniformly low. The IgA response was independent of age.

Effect of serotype.

The association between antibody response and Campylobacter species or C. jejuni serotype was assessed by categorizing typing results in five groups, C. coli; C. jejuni (all serotypes); common C. jejuni serotypes (O:1,44, O:2, and O:4 complex); uncommon C. jejuni serotypes; and unclassified serotypes (not typeable and unknown). The assessed antibody response was independent on these major groups (P > 0.4 for all three antibody classes). However, by comparing the response to C. jejuni O:19 against other classified serotypes, the five O:19 patients had higher IgA values (OD, 0.03 a.u.; 95% CI, 0.00 to 0.10; P = 0.06) and IgM values (OD, 0.07 a.u.; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.22; P = 0.006, adjusted for age). In addition, patients with C. jejuni O:19 had 0.01 a.u. (95% CI, −0.02 to 0.10; P = 0.48) higher IgG values than others. The results were essentially the same when the unclassified types were lumped together with the group of other classified types and included in the analyses.

Cross-reactions.

Sera from patients with infection due to other microorganisms causing gastrointestinal infections were assayed for antibodies against C. jejuni using the ELISA. Sera from 39 patients positive for H. pylori were tested for cross-reactions against heat-stable combination antigen, since H. pylori is phylogenetically the most closely related bacterium to Campylobacter. By using the cut-offs described above for IgG, IgM, and IgA, we found one, four, and six positive samples, respectively. Four sera from patients with E. coli O:157 infection were all found negative. Three groups of 39 sera each from patients with Yersinia O:3, Salmonella, and Legionella infections were assayed, and we found zero, eight, and three; two, four, and two; and zero, zero, and three positive sera, respectively, according to the cut-offs.

Determination of sensitivity.

By using the 90th percentile of the negative sera as a cut-off and thus obtaining a specificity of at least 90%, Campylobacter infection could be detected with a sensitivity of 71% using IgG, 60% using IgM, and 80% using IgA within 35 days after infection. By combining all three antibody classes, the sensitivity was 92%, and after 3 months (90 days) from infection, the combined sensitivity was 90% (IgG, 68%; IgM, 52%; and IgA, 76%). In Fig. 2, ROC curves representing the diagnostic value (sensitivity and specificity) of our test at different times after infection are presented.

FIG. 2.

ROC curves depicting the sensitivity and specificity of Campylobacter serodiagnosis depending on antibody class tested (IgG, IgM, and IgA) and time since infection. The diagnostic sensitivity at different levels of specificity is shown at 0 to 2 months (solid circles), 3 to 5 months (open circles), 6 to 11 months (open diamonds), and 12 to 23 months (open squares) after infection.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to establish an ELISA suitable for a general screening of Campylobacter infections. The assay should be sensitive for the most prevalent C. jejuni and C. coli serotypes and have few or no cross-reactions with other genera.

C. jejuni serotypes O:1,44 and O:53 used as the antigen represent the most common serotypes (18%) and the seventh most common (3%) in Denmark (17). The evaluation of this antigen combination showed that the measured antibody response was independent of the major groups of C. jejuni serotypes and that the assay was also suitable for detecting antibodies against C. coli. The serotype distribution of the 177 isolates in this study was in accordance with earlier studies in Denmark (17). The study included five patients with C. jejuni O:19 infections, and these patients had significantly higher levels of IgM and IgA than others did. C. jejuni O:19 is associated with the most serious disease caused by Campylobacter, Guillain-Barré syndrome (11, 26). The high levels of IgM and IgA in C. jejuni O:19 patients may be related to a higher affinity of the test for antibodies against this serotype than others. However, O:19 was not chosen for the antigen preparation, and it is therefore more likely that the high antibody levels reflect the high immunogenicity of C. jejuni O:19 rather than an increased affinity of the ELISA against this serotype. This view is in line with observations made by Rautelin et al. (19) and warrants further studies. Allos and colleagues have recently shown that C. jejuni O:19 strains, regardless of Guillain-Barré syndrome association, are more serum resistant than non-O:19 strains (1). Our findings corroborate the hypothesis that the elevated immunologic response induced by O:19 strains leads to injury of peripheral nerve structures. None of the five patients with infections caused by C. jejuni serotype O:19 developed Guillain-Barré syndrome.

It was not possible to investigate sera from infections caused by Campylobacter species other than C. jejuni and C. coli, as the current method for the diagnosis of Campylobacter enteritis is culturing of fecal samples on selective medium adjusted to these species. Furthermore, a recent study suggests that C. fetus, C. lari, and C. upsaliensis are minor causes of Campylobacter enteritis in Denmark (8).

The prepared crude antigen showed no cross-reactions based on a 90th percentile towards the phylogenetically most closely related bacterium H. pylori and the other bacteria examined. Earlier works have reported cross-reactions between C. jejuni and H. pylori when using sonicated antigen (12). Cross-reactions between Salmonella serovars Typhi and Paratyphi and C. jejuni have been reported when the antigen used was based on the flagellar protein (13). Finally, cross-reactions of the IgM class between Legionella pneumophila and C. jejuni based on formalin-treated antigen have been reported (5).

Class-specific antibody response profiles were determined over a period of 2 years based on a large number of patients. The IgA response was associated with acute infection. The IgM response was highest in the younger age groups, and there was a significant association between age at infection and IgM response (Table 2). Thus, serodiagnosis based on IgM response is a particularly useful tool for young patients. It is likely that a considerable proportion of elderly persons have a secondary antibody response without IgM elevation. IgG levels were highly individually variable, and this large variability of IgG response was also reflected by a large variation in IgG levels among the negative controls (data not presented). At a 90% specificity, 71, 60 and 80% of acute infections could be detected by IgG, IgM, and IgA, respectively, in a single convalescent-phase sample. By using a combination of all three antibody classes, sensitivity was 92 and 90% within the first 35 days and within 3 months after infection, respectively. Furthermore, the ROC curves show that approximately 50% of the infections can be detected serologically up to 1 year postinfection.

Blaser and coworkers (3) used a glycerol-HCl-extracted surface antigen of serotypes O:1, O:2, and O:3 in their ELISA. For IgG antibodies, the test had a specificity of 74% and 59% sensitivity. For IgM, the specificity was 68% and the sensitivity was 74%, and for IgA the specificity was 81% and the sensitivity was 76%. Thus, the IgA ELISA was the most specific and sensitive assay in their study to detect an acute C. jejuni infection on the basis of a single convalescent-phase serum specimen. This observation is confirmed in the present study, although our ELISA is more specific and sensitive than those described previously (2, 3, 10, 23).

We conclude that measurement of Campylobacter antibodies is a useful diagnostic tool and can also be used for seroepidemiological studies. The high IgM and IgA antibody response against C. jejuni O:19 is of particular interest and corroborates the notion that this C. jejuni serotype, which is frequently associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome, is highly immunogenic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Danish Central Scientific Ethical Committe approved the project. We thank Eva Møller Nielsen, Danish Veterinary Laboratory, for assistance on serotyping and for providing the sera used for serotyping. Special thanks to doctors in general practice and patients without whose kind participation this study would not have been possible.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allos B M, Lippy F T, Carlsen A, Washburn R G, Blaser M J. Campylobacter jejuni strains from patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:263–268. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen L P, Gaarslev K. Campylobacter jejuni/coli: elevated IgA and IgM antibodies during acute infection. In: Ruiz-Palacios G M, Calva F, Ruiz-Palacios B R, editors. Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Campylobacter Infections. Mexico DF, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de la Nutricion; 1991. pp. 221–222. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser M J, Duncan D J. Human serum antibody response to Campylobacter jejuni infection as measured in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect Immun. 1984;44:292–498. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.2.292-298.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaser M J, Duncan D J, Osterholm M, Istre G R, Wang W L L. Serologic studies of two clusters of infection due to Campylobacter jejuni. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:820–823. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boswell T C J, Kudesia G. Serological cross-reaction between Legionella pneumophila and Campylobacter in the indirect fluorescent antibody test. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109:291–295. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005024x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brøndsted T, Hald T, Jørgensen B B, editors. Annual Report on Zoonoses in Denmark 1999. Copenhagen, Denmark: Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries; 2000. Campylobacter jejuni/coli; pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diggle P J, Liang K Y, Zeger S L. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford, U.K: Clarendon Press, Oxford University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engberg J, On S L W, Harrington C S, Gerner-Smidt P. Prevalence of Campylobacter, Arcobacter, Helicobacter, and Sutterella spp. in human fecal samples estimated by a reevaluation of isolation methods for campylobacters. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:286–291. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.286-291.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ismail T F, Wasfy M O, Oyofo B A, Mansour M M, El-Barry H M, Churilla A M, Eldin S S, Peruski L F., Jr Evaluation of antibodies reactive with Campylobacter jejuni in Egyptian diarrhea patients. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:536–539. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.5.536-539.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaldor J, Pritchard H, Serpell A, Metcalf W. Serum antibodies in Campylobacter enteritis. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:1–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.1.1-4.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuroki S, Saida T, Nukina M, et al. Campylobacter jejuni strains from patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome belong mostly to Penner serogroup 19 and contain β-N-acetylglucosamine residues. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:243–247. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mæland J A, Bevanger L, Enge J. Serological testing for campylobacteriosis with sera forwarded for Salmonella and Yersinia serology. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1993;101:647–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1993.tb00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melby K, Tønjum T, Skjørten F. Detection of serum antibody response in patients infected with one strain of Campylobacter jejuni with a DIG-ELISA method. NIPH (Natl Inst Public Health) Ann. 1986;9:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nachamkin I, Engberg J, Aastrup F M. Diagnosis and susceptibility of Campylobacter spp. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, editors. Campylobacter. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2000. pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nachamkin I, Murray E J, Baron M A, Pfaller F C, Tenover F, Yolken R H. Campylobacter and Arcobacter. In: Murray P R, et al., editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 483–491. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nachamkin I. Microbiologic approaches for studying Campylobacter species in patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:S106–S114. doi: 10.1086/513789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen E M, Engberg J, Madsen M. Distribution of serotypes of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli from Danish patients, poultry, cattle and swine. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;19:47–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penner J L, Hennessy J N, Congi R V. Serotyping of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli on the basis of thermostable antigens. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983;2:378–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02019474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rautelin H I, Kosunen T U. Campylobacter etiology in human gastroenteritis demonstrated by antibodies to acid extract antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1944–1951. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.1944-1951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sackett D L, Haynes R B, Guyatt G H, Tugwell P, editors. Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown & Co.; 1991. pp. 69–152. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skirrow M B, Blaser M J. Campylobacter jejuni. In: Blaser M J, Smith P D, Ravdin J I, Greenberg H B, Guerrant R L, editors. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 825–848. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svedhem Å, Gunnarsson H, Kaijser B. Diffusion-in-gel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for routine detection of IgG and IgM antibodies to Campylobacter jejuni. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:82–92. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walder M, Forsgren A. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibodies against Campylobacter jejuni, and its clinical application. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand Sect B. 1982;90:423–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1982.tb00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson K C, Kerr E J C. Comparison of agglutination, complement fixation and immunofluorescence tests in Campylobacter jejuni infections. J Hyg. 1982;88:165–171. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400070042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson K C, Kerr E J C, McFadzean S M. Serology of human Campylobacter infections. J Infect. 1979;1:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuki N, Takahashi M, Tagawa Y, Kashiwase K, Tadokoro K, Saito K. Association of Campylobacter jejuni serotype with antiganglioside antibody in Guillain-Barré syndrome and Fisher's syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:28–33. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]