Abstract

Sixteen strains of Lactobacillus isolated from humans, mice, and food products were screened for their capacity to associate with Peyer's patches in mice. In preliminary experiments, in vitro binding to tissue pieces was assessed by scanning electron microscopy, and it was demonstrated qualitatively that 5 of the 16 strains showed some affinity for the Peyer's patches, irrespective of their association with the nonlymphoid intestinal tissue. Lactobacillus fermentum KLD was selected for further study, since, in addition to its intrinsically high adhesion rate, this organism was found to exhibit a preferential binding to the follicle-associated epithelium of the Peyer's patches compared with its level of binding to the mucus-secreting regions of the small intestine. Quantitative assessment of scanning electron micrographs of tissue sections which had been incubated with L. fermentum KLD or a nonbinding control strain, Lactobacillus delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus, supported these observations, since a marked difference in adhesion was noted (P < 0.05). This preferential association of strain KLD with the Peyer's patches was also confirmed with radiolabeled lactobacilli incubated with intestinal tissue in the in vitro adhesion assay. Direct recovery of L. fermentum KLD from washed tissue following oral dosing of mice revealed a distinct association (P < 0.05) between this organism and the Peyer's patch tissue. In contrast, L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus showed negligible binding to both tissue types in both in vitro and in vivo adhesion assays. It was concluded that L. fermentum KLD bound preferentially to Peyer's patches of BALB/c mice.

Lactobacilli comprise a large percentage of the indigenous flora of the gastrointestinal tract. It has been well documented that lactobacilli exert various beneficial effects on the host, which has led to their classification as a probiotic organism. Although specific health-related claims are generally not made, probiotic bacteria have been shown to possess the ability to inhibit various intestinal pathogens (5, 7), provide a barrier effect, and also modulate the immune function of the host (6, 10, 14), as well as to have a variety of other effects.

Luminal antigens gain access to the mucosal lymphoid tissues via the Peyer's patches in the small intestine. The delivery of vaccines directly to this site could enhance the probability that the host will encounter the immunizing antigen. Although the currently used vaccines are effective, they make use of attenuated pathogenic bacteria such as mycobacteria, salmonellae, and clostridia, many of which have been shown to associate with the Peyer's patches. Lactic acid bacteria are organisms that are generally regarded as safe and are being evaluated for use as a live-vector antigen delivery system (12).

It has been shown that lactobacilli associate with the gastrointestinal tract in a number of ways. Both specific proteinaceous (4, 13) and carbohydrate (8) structures are involved in the adhesion of lactobacilli to various regions within the gastrointestinal tract. The interaction of gram-negative pathogenic bacteria with M cells has been extensively studied (3, 9, 11), and more recently, the interaction of gram-positive bacteria with the surface of M cells has been examined (2). The study described here aims to determine whether lactobacilli associate with the Peyer's patches, in preference to nonlymphoid intestinal tissue, and to examine this adhesion both in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The Lactobacillus strains used in the study (Table 1) were obtained from the Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) for Food Industry Innovation Culture Collection at the University of New South Wales and were maintained as glycerol stocks stored at −70°C. Primary cultures for each experiment were grown from the glycerol stocks by inoculation (1%) into Mann Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) broth (Difco) and incubation for 18 h anaerobically (Don Whitley Scientific Mark 3 Anaerobic Chamber). The bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min, and the pellets were washed twice in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2). The pellets were adjusted to give an optical density at λ600 of 0.5 for use in the in vitro adhesion assay. Bacteria used in the in vivo adhesion assay were concentrated by resuspension in a smaller volume of PBS to yield an optical density of 1.2, which corresponded to approximately 109 CFU ml−1, as determined by serial dilution and plating of the suspension on MRS agar. For the radiolabeling of the bacteria used in the in vitro adhesion assay, the medium was supplemented with [methy-l,1′,2′-3H]thymidine (124 Ci mmol−1) to give a final concentration of 10 μCi ml−1.

TABLE 1.

Strains of Lactobacillus screened for association with mouse Peyer's patch tissue

| Strain | Reference number | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 003 | FII 532700 | Mouse stomach |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 004 | FII 532800 | Mouse stomach |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 005 | FII 532900 | Mouse stomach |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 006 | FII 533000 | Mouse colon |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 008 | FII 533200 | Mouse colon |

| L. fermentum PC1 | FII 511400 | Human feces |

| L. acidophilus | FII 504400 | Unknown |

| L. fermentum LMN | FII 511100 | Human feces |

| L. fermentum 104S | FII 511200 | Pig stomach |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain HBL | FII 511300 | Human feces |

| L. paracasei 43338 | FII 530300 | Human feces |

| L. salivarius 43321 | FII 530400 | Human feces |

| L. paracasei 42319 | FII 530500 | Human feces |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 433121 | FII 530600 | Human feces |

| L. bulgaricus | UNSW 046900 | Dairy products |

| L. salivarius subsp. salivarius | ATCC 11741 | Unknown |

Preparation of tissue pieces.

Peyer's patch and nonlymphoid intestinal tissue samples were taken from 6-week-old specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c mice which had been obtained from CULAS, Little Bay, Australia. The tissue pieces were washed so that they were visibly clear of debris and were placed into wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate (Nunc) with the villi facing upwards and with six pieces per well. The tissue pieces obtained were roughly 2 mm2. The tissue pieces were kept on ice for no more than 2 h prior to use.

In vitro adhesion.

The in vitro adhesion assay was conducted as described by Henriksson and Conway (8). Briefly, the radioactively labeled Lactobacillus cells were incubated with the tissue pieces (n = 6 per Lactobacillus suspension) at 37°C for 20 min with constant gentle agitation with an orbital shaker. After the incubation, the tissue pieces were washed three times in 1 ml of PBS with gentle agitation at room temperature for 5 min per wash. The tissue pieces were weighed and then digested with perchloric acid (150 μl) and hydrogen peroxide (300 μl) at 70°C for 12 h in glass scintillation vials. Scintillation fluid (9 ml) was added to each vial, and the radioactivity of the samples was measured after 10 min with a Packard Tricarb 2100TR liquid scintillation counter. Statistical calculations were carried out by the Student t test.

Scanning electron microscopy.

The adhesion assay described above was also conducted with nonradiolabeled lactobacilli. Tissue pieces were prepared for examination by scanning electron microscopy instead of being weighed and digested. Briefly, following the adhesion assay tissue pieces were fixed in glutaraldehyde (3% in PBS) and were dehydrated with a graded ethanol series and 100% dry acetone. The tissue pieces were dried with the E3100 Jumbo Series II Critical Point Drier apparatus (Polaron, Watford, United Kingdom). The tissue pieces were gold coated with a Polaron sputter coater, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mounted sections were examined with a scanning electron microscope (S360; Cambridge Instrument Co., Cambridge, United Kingdom). Fifty randomly selected fields from more than six tissue pieces from at least six individual mice were examined at ×3,000 magnification.

In vivo adhesion.

Specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c mice, as described above, were orally dosed with approximately 109 lactobacilli by orogastric intubation. Each group contained six mice. At 2 h postdosing, the mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and the Peyer's patches and control nonlymphoid intestinal tissue were examined by enumeration of the associated lactobacilli. This was performed by homogenizing the tissue with an Ultra Turrax homogenizer (Janke and Kunkel) and serially diluting and plating aliquots on Rogosa agar (Oxoid). The numbers of lactobacilli were enumerated by counting according to known colony morphologies. The results were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Isolates were confirmed by protein profiling (n = 5), carbohydrate fermentation with an API 30 (BioMérieux) (n = 4), and immunodetection (n = 4) with Lactobacillus fermentum KLD-specific antiserum to positively identify L. fermentum isolates from indigenous organisms.

RESULTS

Examination of the in vitro association of Lactobacillus spp. with the FAE of the Peyer's patches by scanning electron microscopy.

Initial screening of the strains of Lactobacillus which associate with the follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) of the Peyer's patches was performed by adhesion assays. Low levels of association were seen for most of the 16 different strains examined, with negligible Lactobacillus cells detected in most fields when the samples were examined by scanning electron microscopy (Table 2). It can been seen that L. fermentum KLD associated with the FAE in large numbers, while, in contrast, small numbers were observed on the nonlymphoid villous intestinal tissue pieces (Fig. 1). Of the five other strains of Lactobacillus seen to associate with the Peyer's patch tissue, a strong association with the nonlymphoid villous intestinal tissue was also evident. No correlation between the source of the lactobacilli and the pattern of Peyer's patch assocation was evident, with some strains isolated from all sources having affinity for the FAE. L. fermentum KLD and Lactobacillus delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus were selected from the initial screen for further quantification by scanning electron microscopy and using radiolabeled bacterial cells in the adhesion assay. L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus was chosen as a negative control strain because it associated with neither the Peyer's patches nor the nonlymphoid villous intestinal tissue.

TABLE 2.

Association of Lactobacillus strains with mouse Peyer's patches and nonlymphoid intestinal tissue

| Strain | Peyer's patch associationa | Nonlymphoid intestine associationa |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 003 | − | − |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 004 | − | − |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 005 | ++ | + |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 006 | ++ | + |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 008 | − | + |

| L. fermentum KLD | ++ | − |

| L. acidophilus | + | − |

| L. fermentum LMN | − | − |

| L. fermentum 104S | + | − |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain HBL | + | ++ |

| L. paracasei 43338 | ++ | ++ |

| L. salivarius 43321 | − | − |

| L. paracasei 42319 | + | + |

| Lactobacillus sp. strain 433121 | − | − |

| L. bulgaricus | − | − |

| L. salivarius subsp. salivarius | + | − |

The association of Lactobacillus spp. to small intestinal tissue, as visualized by scanning electron microscopy: −, no association; +, low level at association (5 to 50 bacteria/field); ++, high level of association (>50 bacteria/field).

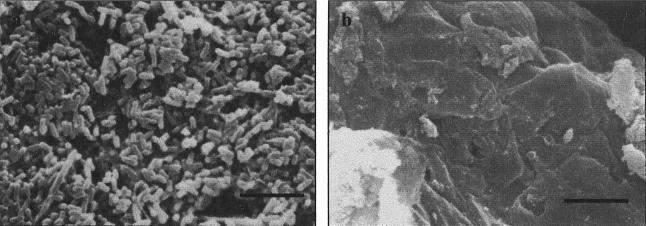

FIG. 1.

Scanning electron micrograph of mouse tissue after incubation in L. fermentum KLD cell suspension. (a) Typical aggregates of L. fermentum KLD-like cells on the FAE of the Peyer's patch; (b) absence of cells on nonlymphoid villous intestine. Bars, 10 μm.

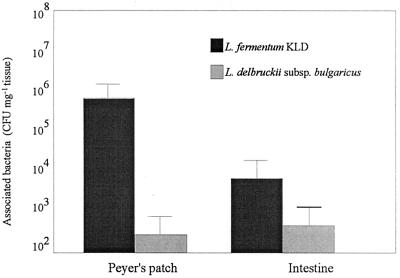

It was shown that L. fermentum KLD bound in large numbers to the FAE domes within the Peyer's patches, with large numbers of bacteria at the surface (Fig. 1a). The level of association with the nonlymphoid villous intestine was usually negligible, irrespective of the presence of mucus on the tissue surface seen in Fig. 1b. By scanning electron microscopy, no association of L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus with either the Peyer's patch tissue or the nonlymphoid villous intestine was demonstrated (data not shown). When this association was quantified by culturing the viable lactobacilli associated with tissue pieces, a similar pattern was noted for L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus (Fig. 2). As can be seen in Fig. 2, L. fermentum KLD did associate to some extent with the villous intestine, but to a lesser degree than was noted for the Peyer's patch tissue.

FIG. 2.

Recovery of viable Lactobacillus cells following a 20-min exposure of L. fermentum KLD and L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus with Peyer's patch and nonlymphoid intestinal tissue. More than 10 tissue pieces from at least six animals were examined. Results are expressed as the the numbers of CFU per milligram (wet weight) of tissue.

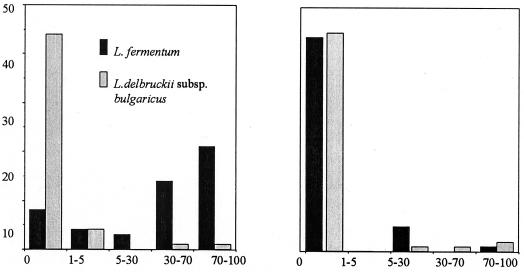

The differences in association of the two Lactobacillus strains examined in 50 randomly selected fields of view with the scanning electron microscope can be seen in Fig. 3. The association of L. fermentum KLD with the FAE of the Peyer's patches was significantly different from the association of L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus with the same regions (P < 0.05), according to the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. No association with the nonlymphoid villous intestinal tissue was demonstrable for the two strains.

FIG. 3.

Association of bacterial cells with Peyer's patches (a) and nonlymphoid intestinal tissue (b) following a 20-min exposure to L. fermentum KLD and L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus and analysis by scanning electron microscopy. Results of the extent of bacterial coverage of the tissue surface when viewed by scanning electron microscopy at ×3,000 magnification are represented as a percentage. Fifty fields with tissue from six animals were examined per treatment.

Examination of the in vivo association of Lactobacillus spp. with the Peyer's patches.

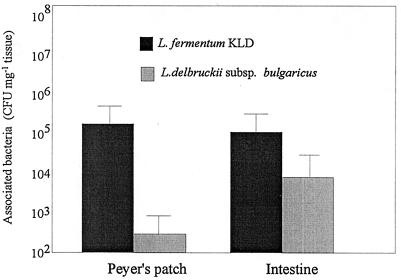

In order to determine whether the association of L. fermentum KLD with the Peyer's patches of mice in vitro was demonstrable in vivo, viable lactobacilli were isolated from small intestinal tissue following oral dosing (Fig. 4). L. fermentum KLD was recovered from both the Peyer's patches and the nonlymphoid villous intestinal regions in numbers significantly greater than those of L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus (P < 0.05), according to the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. As with the in vitro result, there were significant differences between the association of L. fermentum KLD with the Peyer's patches and the association of L. fermentum KLD with the villous intestine (P < 0.05). The association of L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus with both tissue types showed no significant difference, as there were generally no associated viable cells recovered from the tissue homogenates.

FIG. 4.

Association of L. fermentum and L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus with the Peyer's patches and nonlymphoid villous intestine 2 h following administration of an oral dose of 109 viable Lactobacillus cells. Results are expressed as numbers of CFU per milligram (wet weight) of tissue (n = 35 per treatment) as the mean value. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Most of the current knowledge of the adhesion to Peyer's patches is based on the results of studies with gram-negative organisms and pathogens (3, 9, 11), and consequently, this interaction is comparatively well understood. The study described here sought to identify a strain of Lactobacillus that associated directly with the surfaces of the Peyer's patches. The importance of this phenomenon is reflected in the need for improved vectors for foreign antigens in vaccines against enteric diseases, such that mucosal protection can be provided, as well as the need for the exclusion of pathogens such as Escherichia coli from one of the important areas of invasion (1).

The selection of L. fermentum KLD was based on its high degree of association with the FAE of the Peyer's patch and its poor association with the nonlymphoid villous intestine (Table 2), since this would allow the ingested Lactobacillus cells to target the Peyer's patches and not be spread over the entire villous surface. Five other strains also associated with the Peyer's patches but also showed a high degree of association with the nonlymphoid villous intestine (Table 2). L. fermentum 104S was more adhesive to the Peyer's patches than the nonlymphoid intestinal tissue, which reflects results of previous studies which have shown that this strain adheres better to nonsecreting squamous tissue than to secreting gastric epithelium (8). The Peyer's patches are generally considered to be nonsecreting regions of the gastrointestinal epithelium due to the decreased numbers of goblet cells. Hence, the mechanism of adhesion to the squamous nonsecreting regions of the gastrointestinal tract and to the intestinal mucosa could be important when considering adhesion to the Peyer's patches, as they contain columnar cells but no overlying mucus.

The association of L. fermentum KLD with the surface of the Peyer's patches has been shown by an in vitro adhesion assay, as well as by in vivo recovery from the Peyer's patches following orogastric dosing of the strain. Although in most fields of view 30 to 100% of the field was covered by L. fermentum KLD (Fig. 1), this association does not necessarily imply a direct association with the M cells within these regions. Although the in vitro scanning electron microscope analysis reveals that L. fermentum KLD shows a preference for the FAE of the Peyer's patch tissue (Fig. 3), low levels of association were observed in some domes of the Peyer's patches, with some fields showing small numbers of associated bacteria or noncharacteristic adhesion patterns (data not shown). This variation in binding has been reported for other organisms. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL 1344 shows variation in binding to M cells (3) and differential binding to domes. The nonuniform bacterial adhesion to the domes suggests that there are M-cell subtypes present in the domes of the Peyer's patches.

The large degree of association of L. fermentum KLD with the Peyer's patches was particularly evident compared with that for a nonassociating strain of L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus. This strain showed levels of association which were significantly lower than the level of association of L. fermentum KLD with the small intestinal tissue used in this study (Fig. 2). Bacterial cells were rarely seen in scanning electron micrographs of tissue incubated with L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus (Fig. 3). The larger numbers of organisms associated with the tissue following direct recovery from the tissue may be due to a less rigorous washing procedure compared to that used for scanning electron microscope analysis. L. fermentum KLD was highly autoaggregative in most of the fields examined (Fig. 2). This suggests not only that there is an association of the lactobacilli with the Peyer's patch surface but also that there are interactions between the bacterial cells. This clumping may be beneficial, as it could further enhance binding to the Peyer's patches and may account for the large numbers of L. fermentum KLD associated with the Peyer's patch surface.

Following administration of an orogastric dose either L. fermentum KLD or L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus to mice, it was observed that L. fermentum KLD associated with tissue in significantly larger numbers than L. delbruckii subsp. bulgaricus when measured by direct enumeration of viable cells from the tissue surface (Fig. 4). In this study, the tissue was sampled 2 h after orogastric intubation. It has previously been shown that the transit time through the entire gastrointestinal tract of mice is approximately 3.5 h (Xin Wang, personal communication). It is therefore assumed that 2 h after incubation, the Lactobacillus cells would have reached the terminal ileum. The same trend was observed for the association with the nonlymphoid villous intestine. As observed in the in vitro adhesion assay, large numbers of L. fermentum KLD were recovered from the nonlymphoid villous intestine sections (Fig. 2). However, the association with the Peyer's patches was statistically more significant (P < 0.05) than the association with the nonlymphoid villous intestine, suggesting that L. fermentum KLD does preferentially associate with the Peyer's patches in vivo.

The results of this investigation indicate that L. fermentum KLD is able to associate directly with Peyer's patches in mice, both in vitro and in vivo. The tissue association of L. fermentum KLD was determined by comparison with that of a nonassociating strain of Lactobacillus. The association is further supported by the persistence of this organism within the gastrointestinal tract for greater than 10 h and its high survival rate in this system (L. Plant, unpublished observation). This study has provided novel evidence that lactobacilli associate with the Peyer's patches in the murine intestine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge financial support from the CRC for Food Industry Innovation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg R D, Garlington A W. Translocation of certain indigenous bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract to the mesenteric lymph nodes and other organs in a gnotobiotic mouse model. Infect Immun. 1979;23:403–411. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.2.403-411.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borghesi C, Regoli M, Bertelli E, Nicoletti C. Modifications of the follicle-associated epithelium by short-term exposure to a non-intestinal bacterium. J Pathol. 1996;180:326–332. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199611)180:3<326::AID-PATH656>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark M A, Jepson M A, Simmons N L, Hirst B H. Preferential interaction of Salmonella typhimurium with mouse Peyer's patch M cells. Res Microbiol. 1994;145:543–552. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conway P L, Kjelleberg S. Protein-mediated adhesion of Lactobacillus fermentum strain 737 to mouse stomach squamous epithelium. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:1175–1186. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-5-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Petrino S F, De Jorrat M B B, Meson O, Perdigon G. Protective ability of certain lactic acid bacteria against an infection with Candida albicans in a mouse immunosuppression model by corticoid. Food Agric Immunol. 1995;7:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Simone C, Vesely R, Bianchi Salvadori B, Jirillo E. The role of probiotics in modulation of the immune system in man and animals. Int J Immunother. 1993;9:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drago L, Gismondo M R, Lombardi A, De Haen C, Gozzini L. Inhibition of in vitro growth of enteropathogens by new Lactobacillus isolates of human intestinal origin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;153:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henriksson A, Conway P L. Adhesion of Lactobacillus fermentum 104S to porcine stomach mucus. Curr Microbiol. 1996;32:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s002849900069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inman L R, Cantey J R. Specific adherence of Escherichia coli (strain RDEC-1) to membranous (M) cells of the Peyer's patches in Escherichia coli induced diarrhea in rabbits. J Clin Investig. 1983;71:1–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI110737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Link H, Rochat F, Soudan K Y, Schiffrin E. Immunomodulation of the gnotobiotic mouse through colonisation with lactic acid bacteria. In: Mestecky J E A, editor. Advances in mucosal immunology. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owen R L, Pierce N F, Apple R T. M cell transport of Vibrio cholerae from the intestinal lumen into Peyer's patches: a mechanism for antigen sampling and for microbial transepithelial migration. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:1108–1118. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.6.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouwels P H, Leer R J, Shaw M, den Bak-Glashower M-J H, Tielen F D, Smit E, Martinez B, Jore J, Conway P L. Lactic acid bacteria as antigen delivery vehicles for oral immunisation purposes. Int J Food Microbiol. 1998;41:155–167. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rojas M. Studies on an adhesion promoting protein from Lactobacillus and its role in the colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. Thesis. Göteborg, Sweden: Department of General and Marine Microbiology, Göteborg University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiffrin E J, Rochat F, Link-Amster H, Aeschlimann J M, Donnet-Hughes A. Immunomodulation of human blood cells following the ingestion of lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1995;78:491–497. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(95)76659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]