Abstract

This study was performed to evaluate the performance of a saliva collection device (OmniSal) and an enzyme-linked immunoassay (EIA) designed for use on serum samples (Detect HIV1/2) to detect human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antibodies in the saliva of high-risk women in Mombasa, Kenya. The results of the saliva assay were compared to a “gold standard” of a double-EIA testing algorithm performed on serum. Individuals were considered HIV-1 seropositive if their serum tested positive for antibodies to HIV-1 by two different EIAs. The commercial serum-based EIA was modified to test the saliva samples by altering the dilution and lowering the cutoff point of the assay. Using the saliva sample, the EIA correctly identified 102 of the 103 seropositive individuals, yielding a sensitivity of 99% (95% confidence interval [CI], 94 to 100%), and 96 of the 96 seronegative individuals, yielding a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 95 to 100%). In this high-risk population, the positive predictive value of the assay was 100% and the negative predictive value was 99%. We conclude that HIV-1 antibody testing of saliva samples collected with this device and tested by this EIA is of sufficient sensitivity and specificity to make this protocol useful in epidemiological studies.

Because human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antibodies are present in the oral fluid of HIV-1-seropositive subjects, it has been suggested that saliva could be used as an alternative to blood for HIV-1 antibody testing (4, 10). Saliva is a safe, simple, and convenient sample to collect for epidemiological studies for a number of reasons. First, the occupational risks associated with needle-stick accidents and injuries from broken glass collection vials are eliminated (3, 10). Second, although saliva from an HIV-1-infected individual contains antibodies to HIV-1, infectious virus in saliva is rare (1). This makes saliva samples more readily disposable, which is a particularly important consideration in resource-poor settings, where incineration or autoclaving are often not available (10). Third, the saliva collection procedure is noninvasive and painless, thereby increasing patient comfort, acceptability of the method, and compliance with repeated testing. Finally, the likelihood of obtaining an adequate saliva sample is high whereas adequate amounts of blood are sometimes difficult to obtain because of cultural or religious reasons, poor venous access, or lack of adequate collection and storage systems.

Whole saliva is composed of secretions from the salivary, parotid, and submandibular glands along with bacteria, cellular debris, and mucus (5). Therefore, whole saliva is not an ideal substrate for enzyme-linked immunoassays (EIAs), since bacteria may release proteases which may degrade immunoglobulin G (IgG) and since mucus can increase the viscosity of the sample, leading to problems with accurate pipetting (5). In addition, IgG levels in saliva are much lower than those in serum, and some earlier studies of saliva-based HIV-1 testing strategies have shown poor sensitivity and specificity (10). However, recent studies have shown that HIV-1 tests performed on oral fluid samples collected using collection devices designed to improve the suitability of samples for EIA testing have had better sensitivity than have tests performed on whole saliva (5). This has been attributed to the presence of preservative fluid in transport media of saliva collection devices, which contains antibacterial and antiproteolytic substances which protect IgG from proteolytic degradation (5, 10).

This study was conducted to evaluate the performance of a saliva collection device in combination with a modified commercial EIA, using paired saliva and serum samples. Saliva-based testing for HIV-1 antibodies would be potentially valuable in epidemiologic surveys and prospective studies and trials in which repeated HIV-1 testing using blood can adversely influence compliance with follow-up and willingness to participate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Paired serum and saliva samples were collected from female prostitutes who were being screened for participation in a prospective cohort study in Mombasa, Kenya (9). The participants gave informed consent for HIV-1 testing and received individual pretest and postest HIV-1 counseling from a trained counselor.

Blood specimens were obtained by venipuncture and were allowed to clot in the collection tube prior to centrifugation for serum separation. Saliva was collected with the OmniSal saliva collection device (Saliva Diagnostic Systems, Vancouver, Wash.). This device is composed of an absorbent pad on a plastic stem and a vial containing transport medium supplemented with antimicrobial and antiproteolytic substances. The subjects were asked to place the absorbent pad under the tongue until the indicator on the stem turned blue, signifying that approximately 1 ml of saliva had been collected. Once the indicator turned blue, the collection pad was transferred immediately to the vial containing the transport medium. The vial was capped and sent at room temperature to the laboratory for testing. All samples were processed within 24 h of collection.

Saliva samples were processed as directed in the OmniSal package insert. The transport tubes containing the collection device were vortexed or flicked against the palm of the hand to detach the pad from the stem. The pad was left in the transport medium, and the stem was discarded. The oral fluid was eluted from the pad by inserting a saliva filter in the tube and gently depressing, leaving a clear supernatant of 1 to 1.5 ml of cell-free fluid.

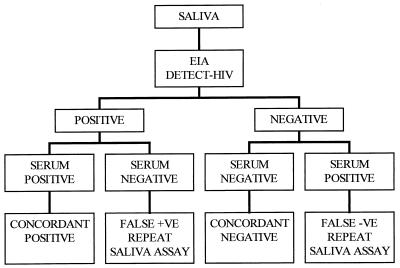

The paired serum and saliva samples were analyzed for HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies by a commercial enzyme immunoassay kit (Detect HIV-1/2; Biochem Immunosystems Inc., Montreal, Canada). Serum samples were tested as specified by the manufacturer, with 5 μl of serum diluted with 250 μl of diluent (1:50 dilution). Serum samples that were reactive were retested with another commercial EIA kit (Recombigen HIV-1/HIV-2 EIA; Cambridge Biotech, Worcester, Mass.), which has a higher specificity than the first EIA. This testing strategy for the screening of HIV antibodies in blood has been recommended by the World Health Organization (11). The saliva samples were tested for HIV-1 antibodies by using a commercial EIA (Detect HIV-1/2) designed for screening blood samples. This EIA was modified according to a protocol recommended by the manufacturer, whereby the volume of sample was increased and the amount of diluent was decreased. For the saliva samples, 50 μl of eluate from the saliva collection device was diluted with 150 μl of the EIA diluent buffer (1:3 dilution). Paired serum and saliva samples for each subject were assayed in the same EIA run each day, with positive and negative controls included each time. Cutoff (CO) values were calculated as specified by the EIA manufacturer by adding a predetermined value of 0.150 to the mean absorption values of the three negative controls. A sample was considered positive if the optical density (OD) was greater than the cutoff value. When a saliva sample yielded a false-negative result compared to the paired serum sample, repeat EIA testing was performed to rule out technical error. The saliva specimen-testing algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Algorithm for testing the saliva samples and comparing with the paired serum sample as the gold standard.

RESULTS

Serum and saliva samples were obtained from 199 high-risk women. Of the 199 subjects, 103 (51.8%) were seropositive for HIV-1. Saliva samples from 100 (97.1%) of the 103 HIV-1-seropositive subjects were EIA positive. The remaining three saliva samples were falsely negative for HIV-1 antibodies, even after repeat testing. The sensitivity of testing for HIV-1 antibodies in saliva using the modified serum-based EIA assay in combination with the OmniSal collection device was 97% (95% confidence interval [CI], 91 to 99%). The specificity of this method was 100% (95% CI, 95 to 100%), since there were no false-positive saliva results.

The mean optical density values (OD) and the OD/cutoff (OD/CO) ratios in serum and saliva among subjects testing concordantly positive, concordantly negative, and falsely negative in the saliva assay are shown in Table 1. These results show that there was a high OD among the seropositive women, reflecting a high titer of HIV antibodies in the serum, even for the three subjects whose saliva samples tested falsely negative. The mean OD of the sera of subjects who tested falsely negative by the saliva assay were no different from the OD of the sera of subjects who were concordantly positive (3.213 and 3.163, respectively; P = 0.8). The saliva OD and OD/CO ratios of the three false-negative samples were significantly higher than the values among concordantly negatives (0.103 versus 0.030 and 0.593 versus 0.178, respectively; P < 0.001 for both).

TABLE 1.

Mean EIA OD values and OD/CO ratios by test result

| OD and OD/CO | Value for paired serum-saliva samplea

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant negative (n = 96) | P1a | Concordant positive (n = 100) | P2a | Discordant (false-negative saliva test, n = 3) | P3a | |

| Saliva OD | 0.030 | <0.001 | 1.183 | <0.001 | 0.103 | <0.001 |

| Saliva OD/CO | 0.178 | <0.001 | 11.017 | <0.001 | 0.593 | <0.001 |

| Serum EIA 1 OD | 0.025 | <0.001 | 3.213 | 0.8 | 3.163 | <0.001 |

| Serum EIA 1 OD/CO | 1.150 | <0.001 | 19.330 | 0.3 | 18.211 | <0.001 |

| Serum EIA 2 OD | 1.218 | 0.5 | 1.138 | |||

| Serum EIA 2 OD/CO | 3.666 | 1.0 | 3.657 | |||

t test for comparison of means: P1 compares concordant positive to concordant negative, P2 compares discordant to concordant positive, and P3 compares discordant to concordant negative.

The EIA OD in the three false-negative samples are shown in Table 2. There were two saliva samples (samples 2 and 3) with relatively high OD values, although they fell below the CO value and were classified as HIV-1 negative. The EIA OD from the serum samples of these three women were similar, as shown in column 2. To improve the sensitivity of saliva-based assays, the minimum and maximum OD values in the EIAs of the concordantly positive and concordantly negative saliva samples were compared to redefine an acceptable lower CO.

TABLE 2.

OD values of the three false-negative saliva samples

| Saliva sample | Saliva OD | Serum OD | CO value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.062 | 3.036 | 0.167 |

| 2 | 0.132 | 3.180 | 0.174 |

| 3 | 0.117 | 3.272 | 0.180 |

The maximum OD for concordantly negative saliva was 0.104. Among concordantly positive saliva samples, the minimum OD in the EIA was 0.200. Therefore, there was a difference of almost 100% by which the CO value could be adjusted. When the CO value was decreased by 20%, the three false-negative saliva samples remained negative and the sensitivity of the assay remained 97%. By lowering the CO by 30%, one of the three samples became positive. Overall, this increased the sensitivity to 98% while the specificity remained at 100%. When the CO was lowered by 35%, two of the three formerly false-negative saliva samples were classified as positive. Thus, with a downward adjustment of the saliva CO value by 35%, the sensitivity of the saliva assay became 99% (95% CI, 94 to 100%) while the specificity of the assay remained 100% (95% CI, 95 to 100%). If the CO value of the assay was decreased by more than 35%, the specificity of the assay was compromised. In this population with a high prevalence of HIV-1 infection, the positive predictive value of testing saliva for HIV-1 antibodies by using a single modified serum-based EIA with the OD CO decreased by 35% was 100% (95% CI, 95 to 100%) and the negative predictive value was 99% (95% CI, 94 to 100%).

DISCUSSION

In this study of HIV-1 antibody detection in saliva collected using the OmniSal collection device and Detect-HIV 1/2 EIA, the assay was 99% sensitive and 100% specific when the optimal CO value for defining a positive result was used. Recently, a similar study conducted in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, which also used the OmniSal collection device for saliva collection, reported a sensitivity and specificity of 99.4 and 99.3%, respectively (2). That study used an EIA kit designed for testing HIV antibodies in body fluids, while our study involved modifying a commercial EIA designed for testing HIV antibodies in blood samples. Commercial EIAs designed for testing serum samples are widely available and cost less than EIAs which are specifically designed for detecting HIV-1 antibodies in body fluids. In a high-risk population such as the one we studied in Mombasa, the positive and negative predictive values (100 and 99%, respectively, in this study) are excellent and saliva is a good alternative to blood for detection of HIV-1 antibodies in epidemiologic surveys and prospective studies (2–4, 12). The HIV-1 subtypes detected in our cohort included A, D, and C, demonstrating that this screening protocol can perform well in populations in which these viral subtypes are predominant (8).

The three saliva samples falsely classified as negative by the assay before the CO value was lowered had OD and OD/CO ratios higher than those present in concordantly negative samples but below the CO values. This suggests that some HIV-1 antibodies were detected in the saliva of these three subjects. This finding could be due to low levels of salivary antibodies, although it could also be due to improper sample collection or handling, resulting in an inadequate amount of saliva or degradation of the IgG. It is also possible that these anti-HIV-1 antibodies were simply poorly detected by the EIA method used.

When the OD CO value of the saliva EIA was decreased by 35%, the sensitivity increased from 97 to 99% while the specificity was maintained at 100%. This manipulation of CO values has been suggested by other authors (3, 6, 7) and may lead to greater sensitivity of this HIV-1 antibody detection method. In this study, the sample size was rather small (199 paired samples) and the subjects were from a population with a high prevalence of HIV-1 infection. Hence, lowering the CO to achieve a more sensitive assay might adversely affect the positive predictive value of the testing algorithm if samples were collected from a population with a lower prevalence of HIV-1 infection.

In the ongoing commercial sex worker cohort studies in Mombasa, blood samples are collected from each patient on a monthly basis for HIV-1 serologic testing. In focus group discussions with participants in these studies, women report that repeated venipuncture and concern about the amount of blood taken represent serious barriers to participation and follow-up. This evaluation of a saliva-based testing method was conducted to determine if the results were comparable to those of serum-based assays for HIV-1 antibodies in order to reduce the frequency of phlebotomy, thereby encouraging compliance with follow-up. Since saliva collection is painless and noninvasive and does not involve venipuncture, the subjects who were screened for this study were enthusiastic about future use of this saliva collection system. The safety of using saliva, the ease of saliva collection, the stability of the collected specimen at room temperature (10), and the sensitivity and specificity make the described HIV-1 antibody testing strategy using the OmniSal collection device in combination with the modified Detect HIV 1/2 EIA an ideal strategy for epidemiologic studies in a variety of settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our thanks to the laboratory staff in the research laboratory at Coast Provincial General Hospital, the nurses at the Ganjoni clinic, and Biochem Immunosystems Inc. (manufacturers of the Detect HIV1/2 EIA) for advising on the dilutions for testing saliva samples.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants D43-TW00007 and T22-TW00001 and through Family Health International (subcontract N01-A1-35173-119).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barr C E, Miller L K, Loper M R, Croxson T S, Shwartz S A, Denman H, Jandorek R. Recovery of infectious HIV-1 from whole saliva. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:39–48. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1992.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettiègne-Traoré V, Ghys P D, Maurice C, Hoyi-Adonsou Y M, Soroh D, Adom M L, Teurquetil M J, Diallo M O, Laga M, Greenberg A E. Evaluation of an HIV saliva test for the detection of HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies in high-risk populations in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Int J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 1998;9:173–174. doi: 10.1258/0956462981921819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frerichs R R, Htoon M T, Eskes N, Lwin S. Comparison of saliva and serum for HIV surveillance in developing countries. Lancet. 1992;340:1496–1499. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frerichs R R, Silarug N, Eskes N, Pagcharoenpol P, Rodklai A, Thangsupachai S, Wongba C. Saliva based HIV-antibody testing in Thailand. AIDS. 1994;8:885–894. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallo D, George J R, Fitchen J H, Goldstein A S, Hindahl M S. Evaluation of a system using oral mucosal transudate for HIV-1 antibody screening and confirmatory testing. JAMA. 1997;277:254–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson A M, Parry J V, Best S J, Smith A M, de Silva M, Mortimer P P. HIV surveillance by testing saliva. AIDS. 1988;2:369–371. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King A, Marion S A, Cook D, Rekart M, Middleton P J, O'Shaughnessy M V, Montaner J S G. Accuracy of a saliva test for HIV antibody. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;9:172–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long M E, Martin H L, Kreiss J K, Rainwater S M, Lavreys L, Jackson D J, Rakwar J, Mandaliya K, Overbaugh J. Gender differences in HIV-1 diversity at time of infection. Nat Med. 2000;6:71–75. doi: 10.1038/71563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin H L, Nyange P M, Richardson B A, Lavreys L, Mandaliya K, Jackson D J, Ndinya-Achola J O, Kreiss J. Hormonal contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk of heterosexual transmission of HIV-1. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1053–1059. doi: 10.1086/515654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamashiro H, Constantine N T. Serological diagnosis of HIV infection using oral fluid samples. Bull WHO. 1994;72:135–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamashiro H, Maskill W, Emmanuel J, Fauquex A, Sato P, Heymann D. Reducing the cost of HIV antibody testing. Lancet. 1993;342:87–90. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Akker R, van den Hoek J A, van den Akker W M, Kooy H, Vijge E, Roosendaal G, Coutinho R A, van Loon A M. Detection of HIV antibodies in saliva as a tool for epidemiological studies. AIDS. 1992;6:953–957. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]