Abstract

This review describes the authors’ experiences in offering gender-affirming primary care and hormonal care using an evidence-based, interprofessional, and multidisciplinary approach. The authors offer references for best practices set forth by organizations and thought leaders in transgender health and describe the key processes they developed to respectfully deliver affirming care to transgender and nonbinary patients.

Keywords: Transgender, Nonbinary, Primary care, Care navigation, Telehealth, Gender affirmation care, Social determinants of health

Key points

-

•

Describe the authors’ process for providing affirming health care for transgender and nonbinary people.

-

•

Describe the authors’ experiences with telehealth to help facilitate care delivery for transgender and nonbinary people.

-

•

Review some best practices and resources in delivering care for transgender and nonbinary people.

Introduction

Transgender people have a gender identity that does not align with the sex they were assigned at birth. The number of transgender people in the United States is not exactly known because many vital statistics and official records, including the United States Census, do not record gender identity. Studies estimate the number of transgender people in the United States to be between 1 million and 1.4 million adult Americans.1 , 2 Younger adults are more likely to identify as transgender or nonbinary and approximately 2% of high school students self-identify as transgender in a 2017 national survey.3 For primary care health professionals, changing patient demographics necessitate both clinical competence and cultural fluency in working with transgender and nonbinary (TGNB) patients. To better serve diverse patients and communities, health professionals need to be aware of the health concerns and challenges facing TGNB people, familiarize themselves with best practices and models of care in serving TGNB patients, and have awareness of the environmental factors that can affect health outcomes for TGNB people. In this article, the authors discuss health concerns facing TGNB communities, address clinical and environmental factors that have an impact on TGNB care, examine best practices that promote optimal health outcomes for TGNB people, and share their experiences in developing tools to provide affirming and respective care for TGNB people.

Health concerns, disparities, and barriers to care for transgender and nonbinary people

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine published “The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding.” This report was among the first to comprehensively assess the health needs and gaps for sexual and gender minority people in the United States.4 Poor health outcomes and health care discrimination experienced by TGNB people have been documented in the 2015 US Transgender Survey, where respondents reported that in the 12 months before the survey nearly 1 in 4 respondents had problems with health insurance coverage because they were transgender, 55% of respondents were denied coverage for transition-related surgery, 33% of respondents had a negative experience with a health care provider/system, and 23% of survey respondents avoided seeing a doctor when needed due to fear of being mistreated for being transgender.5

In the United States and globally, health concerns and disparities affecting transgender people have focused on mental health, sexual and reproductive health, substance use, violence and victimization, stigma/discrimination, and a variety of general health topics (eg, mortality, hormone use, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cancer).6 A 2016 systematic review of preventive health services for transgender patients found that a majority of studies discussed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) rates or risk behaviors, whereas few studies mentioned tobacco abuse, cholesterol screening or cardiovascular health, or pelvic examinations. No studies reported addressed mammography or chest/breast tissue examinations, colorectal cancer screening, or vaccination against influenza.7

In addition to stigma and experiences of discrimination, TGNB people face barriers to accessing care for general health as well as gender affirmation care, with a lack of providers with expertise contributing the most to restricting health care access.8 Some health professionals, however, have indicated a desire to improve their ability to care for and treat transgender patients and address knowledge gaps.9 , 10 Although education and training in transgender health are outside the scope of this article, tools and resources have been developed in conjunction with models of care that can help health professionals augment their clinical knowledge and hone skills to better care for TGNB patients.

Care guidelines for transgender and nonbinary people

Several guidelines, frameworks, and recommendations11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 have been developed that address various aspects of TGNB care. These guidelines are summarized in Table 1 . Guidelines vary in their scope and content but address health concerns in primary care, gender-affirming hormonal therapy (GAHT), reproductive health and fertility, contraception, sexual health and HIV prevention, mental health, aging, and adolescent health.

Table 1.

Organizational gender affirmation care guidelines and recommendations

| Organization | Year | Title (Citation) | Description (from Web Page/Abstract) |

|---|---|---|---|

| World Professional Association for Transgender Health | 2011 | Standards of Care, Version 711 | Standards of Care, Version 7, provides clinical guidance for health professionals to assist transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. |

| Endocrine Society | 2017 | Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline12 | The 2017 guideline on endocrine treatment of gender dysphoric/gender incongruent persons |

| University of California, San Francisco Transgender Care | 2016 | Guidelines for the Primary and Gender affirmation care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People13 | Guidelines were developed to complement the existing World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care and the Endocrine Society guidelines in that they are specifically designed for implementation in everyday evidence-based primary care, including settings with limited resources. |

| The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health | 2015 | Comprehensive transgender healthcare: the gender affirming clinical and public health model of Fenway Health14 | This report describes the evolution of a Boston community health center's multidisciplinary model of transgender health care, research, education, and dissemination of best practices. |

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | 2011 | Health Care for Transgender Individuals. Committee Opinion No. 51215 | This committee opinion provides guidance and recommendations for the health care of transgender individuals. |

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | 2017 | Care for Transgender Adolescents. Committee Opinion No. 68516 | This committee opinion reflects recommendations for care of transgender adolescents based on the emerging clinical and scientific advances in transgender health. |

| TransLine | 2019 | TransLine Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy Prescriber Guidelines17 | National standardized guideline of best practices in hormonal therapy provision as a reference to achieve uniformity for the Transgender Medical Consultation Service. |

Additionally, recent books and articles on TGNB health describe not only how to deliver comprehensive primary and gender affirmation care to TGNB people18, 19, 20, 21, 22 but also the importance of including cancer surveillance,23, 24, 25, 26 the fertility concerns of transgender patients,27 pregnancy in transgender men,28, 29, 30 mental health,31 , 32 recognizing the effects of self-prescribed gender affirmation care33, 34, 35 as well as HIV care36 and social determinants of health.37 , 38 These resources are presented in Table 2 . A full discussion of the role of patient-centered communication,39 Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning (LGBTQ)-affirming clinical environments,40 legal resources for name changes,41 and sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data in electronic health records (EHRs)42 falls outside the framework for this article, but the importance of each of these elements is recognized in establishing and maintaining relationships of trust with TGNB patients, especially at their initial point of contact.

Table 2.

Selected clinical articles and resources

| Care Domain | Title (Citation) | Authors | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General/primary care | Comprehensive Care of the Transgender Patient, 1st Edition18 | Ferrando CA | 2020 | A multidisciplinary resource on transgender health care and surgery covering many aspects of transgender health care, including epidemiology and history, mental health services, endocrine and hormone therapy treatment, and surgical options |

| Care of the Transgender Patient19 | Safer JD et al. | 2019 | Guide published by the American College of Physicians to assist primary care and family medicine physicians in caring for transgender patients | |

| Caring for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Persons: What Clinicians Should Know20 | Klein DA et al. | 2018 | The article describes key information clinicians should know when caring for transgender and gender-diverse persons. | |

| Best Practices in LGBT Care: A Guide for Primary Care Physicians21 | McNamara M and Ng H | 2016 | This article reviews some best practices for health screening and care for LGBT people. | |

| Trans Bodies, Trans Selves22 | Erickson-Schroth L (editor) | 2014 | Comprehensive guide and resource for TGNB people, written by TGNB people | |

| Cancer surveillance | Female-to-male patients have high prevalence of unsatisfactory Paps compared to non-transgender females: implications for cervical cancer screening.23 | Peitzmeier SM et al. | 2014 | Research article examining Pap tests results at an urban community health center demonstrating femaleto -male patients had more unsatisfactory examinations |

| Cancer in Transgender People: Evidence and Methodological Considerations24 | Braun H et al. | 2017 | Comprehensive review of cancer epidemiology in TGNB people | |

| Breast cancer risk in transgender people receiving hormone treatment: nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands25 | de Blok Christel JM et al. | 2019 | Retrospective cohort study on breast cancer incidence and characteristics among transgender people in the Netherlands | |

| Cancer Screening for Transgender and Gender Diverse Patients26 | Grimstad F et al. | 2020 | Review of sex-trait related cancer risks and screening guidelines in transgender and gender-diverse populations | |

| Reproductive/sexual health and fertility | From Erasure to Opportunity: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Transgender Men Around Pregnancy and Recommendations for Providers28 | Hoffkling A et al. | 2017 | Exploratory qualitative study on the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy |

| Fertility Concerns of the Transgender Patient27 | Cheng PJ et al. | 2019 | Review article describing the fertility issues and concerns transgender people face | |

| Transgender men and Pregnancy29 | Obedin-Maliver J and Makadon H | 2016 | Commentary providing guidance to clinicians caring for transgender men or gender nonconforming people who are contemplating, carrying or have completed a pregnancy | |

| Family Planning and Contraception Use in Transgender men30 | Light A et al. | 2018 | Exploratory study describing current contraceptive practices and fertility desires of transgender men during and after transitioning | |

| Mental health | Transgender Mental Health31 | Erickson-Schroth L and Carmel T | 2016 | Guest editorial for a special issue of Psychiatric Annals addressing mental health concerns for transgender people |

| Gender Dysphoria in Adults: An Overview and Primer for Psychiatrists32 | Byne W et al. | 2018 | White paper describing the diagnostic nosology, epidemiology, gender development, mental health assessment, differential diagnosis, treatment and referral for gender-affirming somatic treatments in adults with gender dysphoria | |

| Gender-affirming hormonal therapy self-care | Structural Inequities and Social Networks Impact Hormone Use and Misuse Among Transgender Women in Los Angeles County33 | Clark K et al. | 2018 | Quantitative study examining associations between medically monitored hormone use, hormone misuse, structural inequities and social dynamics in a cohort of transgender women |

| Nonprescribed Hormone Use and Self-Performed Surgeries: “Do-It-Yourself” Transitions in Transgender Communities in Ontario, Canada34 | Rotondi NK et al. | 2013 | Case series describing nonprescribed hormone use and self-performed surgeries among a cohort of transgender adults | |

| Tranitioning Bodies: The Case of Self-Prescribing Sexual Hormones in Gender Affirmation in Individuals Attending Psychiatric Services35 | Metatasio A et al. | 2018 | Case series describing transgender and gender nonconforming individuals self-prescribing and self-administration of hormones without medical; consultation | |

| Social determinants of care | Barriers and Facilitators to Engagement and Retention in Care Among Transgender Women Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus36 | Sevelius JM et al. | 2014 | Qualitative study examining culturally unique barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in HIV care among transgender women |

| A Preliminary Assessment of Selected Social Determinants of Health in a Sample of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals in Puerto Rico37 | Martinez-Velez JJ et al. | 2019 | Survey study using a community-based participatory research approach exploring social determinants of health affecting a cohort of transgender and gender nonconforming adults | |

| Social Determinants of Discrimination and Access to Health Care Among Transgender Women in Oregon38 | Garcia J and Crosby RA | 2020 | Qualitative study exploring social determinants affecting patients’ access to gender affirmation care |

Delivering transgender and nonbinary–affirming primary care and hormonal care: the authors’ experiences

In March 2020, the authors’ updated the patient intake process for TGNB people with a goal of “meeting patients where they are” amid the COVID-19 pandemic for safe, inclusive, and streamlined care. As patients call to schedule their initial visit for gender-affirming care, a scheduler administers a scheduling questionnaire in the EHR, prompting the call to be transferred to the Center for LGBTQ+ Care clinic coordinator. The coordinator identifies what services the patient is requesting and connects them to the appropriate service accordingly. If medical gender affirmation care is requested, the patient’s information is routed to the medical team patient navigator (PN) in the EHR.

The PN contacts the patient to complete registration and demographic information in the EHR, including the “name the patient goes by” (a term the authors’ group feels is more affirming than using “preferred name”) and their pronouns, assists with activating an EHR patient portal account, and sends a code of conduct electronically for the patient to review and agree to. If a patient lacks health insurance coverage or has out-of-network insurance, the PN assists in linking the patient to a patient financial advocate to identify potential assistance program resources. Once completed, the PN schedules an in-person or telehealth visit with a provider based on the patient’s preference. Additionally, the PN assures each patient has transportation to the appointment and offers to arrange through the patient’s insurance or local agencies if needed.

An intake form then is sent via the patient’s EHR portal to complete the collection of SOGI data, health history, and specifically the patient’s experience of gender, goals of care, and thoughts around fertility, contraception, and creating families. The form is presented in Appendix 1. The authors’ electronic questionnaire is used with the philosophy of respectful inquiry when inquiring about potentially sensitive topics, such as sexuality and gender identity. If the intake is not completed, the patient is reminded that this helps tailor their plan of care to the patient’s goals while maintaining safety. Once the intake by the PN is completed, patients are contacted by a support resource nurse (SRN) to complete a clinical intake, including determination of specific clinical care needs, clarify and set expectations for the upcoming appointment, and assess the need for laboratory testing and referrals. Patients also are provided the opportunity for referrals at that time for routine gynecologic care and cancer prevention as well as counseling for fertility preservation and referral of fertility services, according to recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.15 , 16

Patients are seen by caregivers, who are nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians with formal training and years of clinical experience with gender affirmation care. Other learners and trainees also may participate in the patient’s care with their permission. Initial visits often are performed via telehealth with video or Zoom-supported calls or telephone calls, where the provider reviews the patient’s goals for the visit and ongoing clinical care, their existing care team, their health and anatomic inventory, their gender experience and gender care goals, and family planning, fertility, and reproductive health needs. The authors’ patients, like many, have performed many hours of their own review of available online resources about transgender care. These resources range from care paths described by academic centers and health centers focused on TGNB care to subreddit forum posts and YouTube videos of TGNB people sharing their experiences with their gender affirmation care. Due to many barriers to care, TGNB communities often turn to social media as self-serve resource for medical knowledge.43 The caregivers recognize the importance of affirming patients’ use of e-health, a concept of using technology to improve the quality of health care, to explore gender on their road to self-discovery.44 As described by Eysenbach,44 the authors’ team strives to address several of the “10 e’s in “e-health”’ including empowering TGNB patients’ understanding of their care through an exchange of ideas around evidence-based interventions and shared decision making.

Informed consent for initiation or continuation of gender affirmation care is reviewed with patients and referrals to health services, such as mental health support and fertility preservation specialists, are made as appropriate. Hormonal care is initiated after patients have completed a physical examination and laboratory testing and have had a thorough discussion of the nuances of gender affirmation care, including microdosing (the use of hormonal treatments at doses lower than that of typical standard starting doses), medication administration, and insurance coverage in addition to reviewing the partially and completely irreversible effects of hormonal medications. The authors offer hormonal treatments like those described by TransLine Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy Guidelines.17

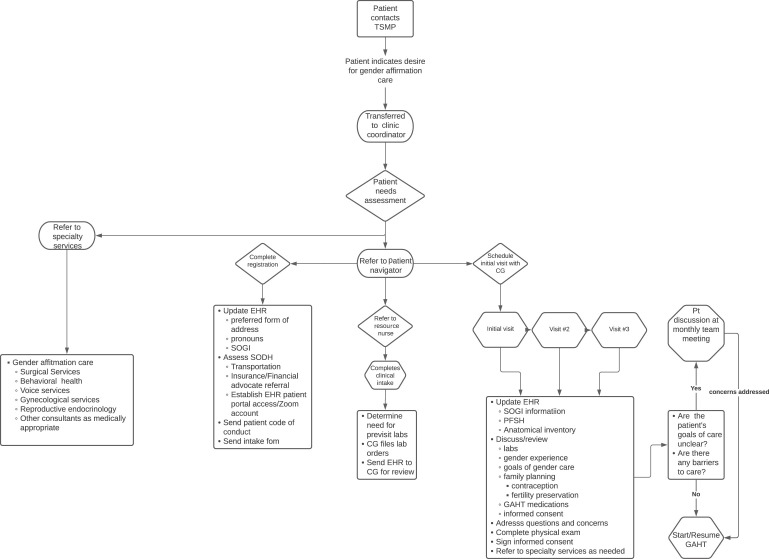

Sometimes, patients presenting for gender affirmation care may have unclear goals of care, medical, psychological, or other factors that may have an impact on their successful gender care and transition. In those instances, the authors review those patients in a multidisciplinary and interprofessional team meeting to determine the next steps of care to address a patient’s gender care needs while promoting their well-being and safety. Fig. 1 summarizes the care navigation process and steps employed to provide patients affirming care at the authors’ center.

Fig. 1.

Patient care navigation for gender affirmation care. CG, caregiver—doctor of medicine/doctor of osteopathic medicine/nurse practitioner/physician assistant; EHR, electronic health record; GAHT, gender affirmation hormonal therapy; PFSH, past medical history, family history, and social history; Pt, patient; SODH, social determinants of health; SOGI, sexual orientation & gender identity; TSMP, transgender surgery and medicine program.

The authors’ caregivers serve as gender specialists and/or the primary care providers for TGNB patients who come to the authors’ program. As patients progress through their gender affirmation care, they are offered referrals to subspecialty care in the hospital system, including behavioral health, medical specialty, surgical specialty, and gender-confirming surgical care. An interprofessional team is used to help patients achieve their care goals. For example, if patients are prescribed injectable hormonal therapies, they can meet with the SRN for education on injection technique and can contact her for follow-up questions or concerns, including medication coverage assistance. Another example of interprofessional teamwork is collaboration with clinical pharmacy. The caregivers work closely with a dedicated clinical pharmacist with prescribing authority for tobacco cessation treatment who assists with tobacco cessation medication management. Tobacco cessation is important not only for patients’ cardiovascular and pulmonary health but also for those who seek eventual gender-affirming surgeries for optimal postsurgical healing. Finally, the navigation process utilizes the EHR to assess social determinants of health for each patient (insurance status, resource limitations, and so forth) and to identify and remove barriers to care.

Discussion

Since implementing revised intake process, 166 patients have had contact with the authors’ PN and SRN. Feedback on the process has been positive with patients who have shared that the act of asking them for the name they go by and their pronouns can have a profound effect on their experience. Many patients the authors have encountered shared that this was the first medical office to ask them these questions and expressed gratitude toward acts of inclusion. Additional feedback from patients has expressed that having a common caregiver, such as the SRN at primary care, and specialty visits, such as gynecology, have aided in providing them a sense of security and shared rapport in the team-based approach. The authors currently are exploring further opportunities to involve clinical pharmacy beyond tobacco cessation in the care of transgender patients. Pharmacists can have roles in TGNB care, including HIV prevention and treatment as well as helping patients and their families understand the medications used in gender affirmation care to anticipate and manage side effects.45

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has laid bare the disparities that TGNB people face in preserving and promoting their health. With limited personal and financial resources combined with the effects of institutional racism and transphobia, many TGNB patients continue to struggle to overcome structural barriers and microaggressions in their daily health care encounters. For optimal clinical outcomes, patient engagement, and trust-building, clinicians need to be aware of intersectional identities and how discrimination, real and perceived, negatively affects their patients, especially transgender people of color.46 In addition to streamlining and creating affirming care navigation and using evidence-based care guidelines, telehealth has become an important tool to reach and better care for TGNB people. In 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid temporarily expanded coverage for telehealth services, which included reimbursement for diagnoses other than those related to COVID-19 infection, waiving or reducing cost-sharing for telehealth visits, lifting geographic restrictions that patients must be located in a rural area, and allowing providers licensed in one state to see patients in another state. Like many other health organizations, the authors’ center has embraced telehealth to connect patients to health care professionals for all kinds of care, including GAHT services. Telehealth has become a vital part of the authors’ approach to reduce and eliminate barriers to care for TGNB people, and future research is planned to measure the impact of these methods in improving health outcomes and care experiences for TGNB patients.

Clinics care points

-

•

When working with TGNB patients, addressing patients by the name they go by and their pronouns helps create a welcoming clinical environment.

-

•

Health care providers caring for TGNB patients should utilize evidence-based recommendations for transgender-inclusive primary care and gender affirmation care.

-

•

Telehealth can be used to help reduce the anxiety and burden faced by TGNB patients who seek gender affirmation care, especially for those who reside away from urban centers.

-

•

TGNB people face multiple barriers to care at the interpersonal, institutional, and policy levels. Health organizations serving TGNB people should help their patients navigate health care systems and barriers related to social determinants of health.

-

•

Interprofessional and multidisciplinary approaches to gender affirmation care can promote patient satisfaction and help patients achieve their individual care goals.

Acknowledgments

This scholarly work could not have been done without the leadership and efforts of our program’s progenitor, Dr Cecile Ferrando, the Medical Director for the Transgender Surgery & Medicine Program at the Cleveland Clinic. Additionally, we are grateful for the technical expertise offered by Richard Dimmock who helped with refining the figures shared in this article.

Disclosure

The authors have no commercial or financial conflicts of interest to disclose. There are no funding sources to disclose.

Supplementary data

Cleveland clinic transgender surgery and medicine program intake form

References

- 1.Meerwijk E.L., Sevelius J.M. Transgender population size in the united states: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores A.R., Herman J.L., Gates G.J., et al. The Williams Institute; Los Angeles (CA): 2016. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johns M.M., Lowry R., Andrzejewski J., et al. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students — 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:67–71. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. The health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and transgender people: building a Foundation for better understanding. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James S.E., Herman J.L., Rankin S., et al. National Center for Transgender Equality; Washington, DC: 2016. Executive summary of the report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender survey. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reisner S.L., Poteat T., Keatley J., et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):412–436. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00684-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edmiston E.K., Donald C.A., Sattler A.R., et al. Opportunities and gaps in primary care preventative health services for transgender patients: a systemic review. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):216–230. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safer J.D., Coleman E., Feldman J., et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):168–171. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shires D.A., Stroumsa D., Jaffee K.D., et al. Primary care clinicians' willingness to care for transgender patients. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(6):555–558. doi: 10.1370/afm.2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paradiso C., Lally R.M. Nurse practitioner knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs when caring for transgender people. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):47–56. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvaggi G., Dhejne C., Landen M., et al. The 2011 WPATH standards of care and penile reconstruction in female-to-male transsexual individuals. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:581712. doi: 10.1155/2012/581712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hembree W.C., Cohen-Kettenis P.T., Gooren L., et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869–3903. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsch M.B., editor. UCSF Transgender Care, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People. 2nd edition. Deutsch MB, ed; June 2016. transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reisner S.L., Bradford J., Hopwood R., et al. Comprehensive transgender healthcare: the gender affirming clinical and public health model of Fenway Health. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):584–592. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9947-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health care for transgender individuals. Committee Opinion No. 512. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1454–1458. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823ed1c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Care for transgender adolescents. Committee Opinion No. 685. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e11–e16. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Transline Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy Prescriber Guidelines. 2019. https://transline.zendesk.com/hc/en-us/articles/229373288-TransLine-Hormone-Therapy-Prescriber-Guidelines Available at: Accessed August 27, 2020.

- 18.Ferrando C.A. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2020. Comprehensive care of the transgender patient. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safer J.D., Tangpricha V. Care of the transgender patient. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(1):ITC1–ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC201907020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein D.A., Paradise S.L., Goodwin E.T. Caring for transgender and gender-diverse persons: what clinicians should know. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(11):645–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNamara M.C., Ng H. Best practices in LGBT care: A guide for primary care physicians. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(7):531–541. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.83a.15148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erickson-Schroth L., editor. Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource for the Transgender Community. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peitzmeier S.M., Reisner S.L., Harigopal P., et al. Female-to-male patients have high prevalence of unsatisfactory Paps compared to non-transgender females: implications for cervical cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):778–784. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2753-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun H., Nash R., Tangpricha V., et al. Cancer in Transgender People: Evidence and Methodological Considerations. Epidemiologic Rev. 2017;39(1):93–107. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxw003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Blok Christel J.M., Wiepjes Chantal M., Nota Nienke M., et al. Breast cancer risk in transgender people receiving hormone treatment: nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2019;365:l1652. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimstad F., Tulimat S., Stowell J. Cancer screening for transgender and gender diverse patients. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2020;9:146–152. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng P.J., Pastuszak A.W., Myers J.B., et al. Fertility concerns of the transgender patient. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8(3):209–218. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.05.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffkling A., Obedin-Maliver J., Sevelius J. From erasure to opportunity: a qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(Suppl 2):332. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1491-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obedin-Maliver J., Makadon H.J. Transgender men and pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9(1):4–8. doi: 10.1177/1753495X15612658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Light A., Wang L.F., Zeymo A., et al. Family planning and contraception use in transgender men. Contraception. 2018;98(4):266–269. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erickson-Schroth L., Carmel T. Transgender mental health. Psychiatr Ann. 2016;46:330–331. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Byne W., Karasic D.H., Coleman E., et al. Gender dysphoria in adults: an overview and primer for psychiatrists. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):57–70. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark K., Fletcher J.B., Holloway I.W., et al. Structural inequities and social networks impact hormone use and misuse among transgender women in los angeles county. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(4):953–962. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1143-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rotondi N.K., Bauer G.R., Scanlon K., et al. Nonprescribed hormone use and self-performed surgeries: "do-it-yourself" transitions in transgender communities in Ontario, Canada [published correction appears in Am J Public Health. 2013 Nov;103(11):e11] Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1830–1836. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metastasio A., Negri A., Martinotti G., et al. Transitioning Bodies. The Case of Self-Prescribing Sexual Hormones in Gender Affirmation in Individuals Attending Psychiatric Services. Brain Sci. 2018;8(5):88. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8050088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sevelius J.M., Patouhas E., Keatley J.G., et al. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(1):5–16. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9565-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Velez J.J., Melin K., Rodriguez-Diaz C.E. A Preliminary Assessment of Selected Social Determinants of Health in a Sample of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals in Puerto Rico. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):9–17. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2018.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia J., Crosby R.A. Social Determinants of Discrimination and Access to Health Care Among Transgender Women in Oregon. Transgend Health. 2020:225–233. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2019.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross K.A., Castle Bell G. A Culture-Centered Approach to Improving Healthy Trans-Patient–Practitioner Communication: Recommendations for Practitioners Communicating with Trans Individuals. Health Commun. 2017;32(6):730–740. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1172286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keuroghlian A.S., Ard K.L., Makadon H.J. Advancing health equity for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people through sexual health education and LGBT-affirming health care environments. Sex Health. 2017;14:119–122. doi: 10.1071/SH16145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill B.J., Crosby R., Bouris A., et al. Exploring transgender legal name change as a potential structural intervention for mitigating social determinants of health among transgender women of color. Sex Res Social Policy. 2018;15(1):25–33. doi: 10.1007/s13178-017-0289-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burgess C., Kauth M.R., Klemt C., et al. Evolving Sex and Gender in Electronic Health Records. Fed Pract. 2019;36(6):271–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blotner C., Rajunov M. Engaging transgender patients: using social media to inform medical practice and research in transgender health. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):225–228. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eysenbach G. What is e-health? J Med Internet Res. 2001;3(2):E20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3.2.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redfern J.S., Jann M.W. The evolving role of pharmacists in transgender health care. Transgend Health. 2019:118–130. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2018.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howard S.D., Lee K.L., Nathan A.G., et al. Healthcare experiences of transgender people of color. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2068–2074. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cleveland clinic transgender surgery and medicine program intake form