Abstract

Anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders are frequent in patients with schizophrenia and are associated with greater severity of both positive and negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, poorer functioning and quality of life. Accumulating evidence suggests that atypical antipsychotics may have a role in treating comorbid anxiety symptoms. A systematic review was conducted following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and Cochrane guidelines, selecting randomized control trials (RCTs) that evaluated efficacy of olanzapine on anxiety symptoms in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and included anxiety evaluation scales. We searched PubMed and Web of Science databases for articles in English language available until September 2021. We selected 7 studies (3 with primary data analysis, 4 with secondary data analysis) regarding the use of olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia. In fours studies olanzapine was superior to haloperidol in improving anxiety symptoms. Four studies compared olanzapine versus risperidone: in two of them risperidone was superior to olanzapine, although one study was limited by a relatively small sample size. In the other two there were no significant differences between olanzapine and risperidone-treated patients. One study found that olanzapine and clozapine were comparable in terms of efficacy. Although olanzapine was superior to haloperidol in treating anxiety, this symptom was a secondary outcome measure in most of the considered studies. Future RCTs comparing different antipsychotics and larger sample sizes may allow to develop more solid treatment strategies.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Anxiety, Comorbidity, Olanzapine.

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a common, chronic and severe mental illness defined by the presence of delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized behavior (positive symptoms); by the presence of apathy, avolition, social withdrawal (negative symptoms); and by cognitive disorganization [1,2]. Further complicating the clinical picture of schizophrenia as well as understanding the boundaries and etiology of this condition is the substantial psychiatric comorbidity [3,4]. Anxiety symptoms can occur in up to 65% of patients with schizophrenia. The prevalence of any anxiety disorder (at syndrome level) in this patient group is estimated to be up to 38%, with social anxiety disorder (SAD) being the most prevalent; followed by generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, specific phobia, agoraphobia [5]. Many studies demonstrated that the presence of an anxiety disorder such as SAD or GAD was associated with more than 3 times increased odds of developing schizophrenia [6]. Anxiety can be a prodromal manifestation of schizophrenia in about 8% of patients [7] and it may also manifest itself as a symptom during an acute psychotic episode [8]. In schizophrenia, higher levels of anxiety are associated with greater levels of hallucinations, withdrawal, depression, despair, worse response to treatment, medical service utilization, cognitive impairment, poorer function, more severe positive symptoms, higher suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior [9-13]. For these reasons, although treating the anxiety dimension may improve the clinical presentation of schizophrenia, the body of data provided by research to date is still far from allowing evidence-based conclusions [9]. There is little evidence for augmentation of antipsychotic therapy with antidepressants, anxiolytics [14], L-theanine [15], cannabidiol [16] and pregabalin [17] whereas treatment with antipsychotics can both improve and worsen comorbid anxiety symptoms [18]. While some efficacy differences between typical and atypical antipsychotics on specific symptom domains (e.g., negative symptomatology) are observed [19], no study assessed the comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in the treatment of the anxiety dimension of schizophrenia and the relationship between their individual receptor profile and the clinical effect on this specific sub-domain. Preliminary data from an open label study suggests that olanzapine monotherapy has a beneficial effect on comorbid anxiety symptoms [20] while results from a single blind RCT show that olanzapine at dose of 20 mg was superior to olanzapine at mean dose of 11 mg in reducing anxiety symptoms in acute schizophrenia [21]. The aim of the study is to evaluate, through a systematic review of the literature, the efficacy of olanzapine compared to placebo or active therapy in the anxiety dimension of schizophrenia.

METHODS

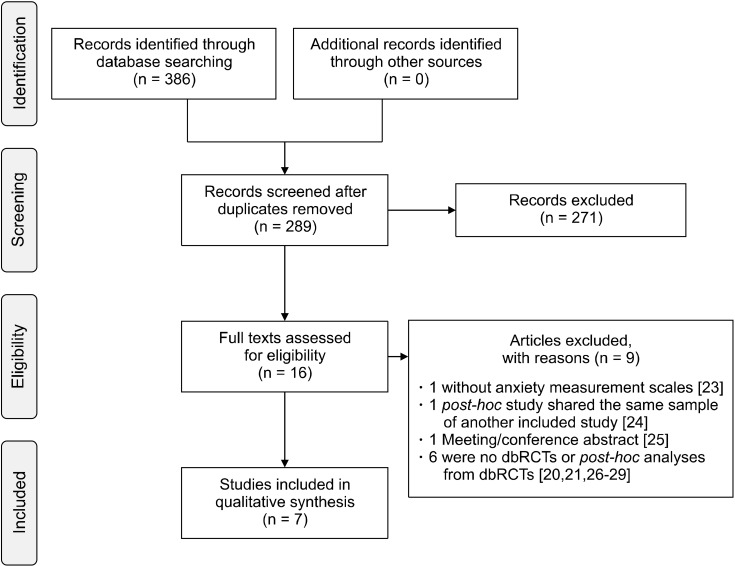

We conducted a systematic review of the literature available between 1998 and September 2021. PubMed and Web of Science (all databases) were searched using the following search builder: (olanzapine AND anxiety AND schizophrenia). Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) design criteria [22] for study selection were applied and are reported in Table 1. Articles not in English were excluded. A total of 386 (252 Web of Science, 134 PubMed) items were retrieved from the search databases and reference cross-check. Duplicates were removed. The remaining studies were independently evaluated by 2 reviewers (C.C. and C.A.) and included or excluded (9 with reasons [20,21,23-29]) after reaching a final consensus (Table 2). Four studies reported post hoc analyses on previously collected data. These studies were included as they allowed a more comprehensive review on the topic (Table 2). Figure 1 reports a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart regarding information process through the different phases of this review [30]. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [31] considering the following items: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias as illustrated in Table 3.

Table 1.

PICOS criteria for study selection

| Parameter | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the ICD/DSM criteria, any version Age ≥ 18 years | |

| Intervention | Olanzapine monotherapy, any dose | |

| Comparator | Placebo or other pharmacological treatments | |

| Outcomes | Effect on the anxiety-related symptoms (measured by scores from clinical scales) | Absence of measurements concerning the anxiety dimension |

| Study design | double blind (db) RCT; post hoc analyses of dbRCTs |

PICOS, Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study; ICD, International Classfication of Diseases; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 2.

Descriptive comparison between studies considered

| Source | Study design | Country | Sample (n) | Duration (wk) | Daily average dose (mg) | Change in assessment score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tollefson et al. [38], 1998 | Post-hoc analysis of an RCT | USA Canada |

OLZ (198) HAL (69) PLC (68) |

6 | OLZ = 2.5−7.5 HAL = 10−20 |

OLZ 10 mg and 15 mg superior to PLC for BPRS, HAL no superior to PLC |

| Davis and Chen [36], 2001 | Post-hoc analysis of an RCT | USA Canada |

OLZ (1,987) HAL (809) PLC (118) |

6 | OLZ = 1−20 HAL = 5−20 |

OLZ superior to HAL for BPRS and PANSS |

| Conley and Mahmoud [42], 2001 | RCT | USA | OLZ (189) RIS (188) |

8 | OLZ =12 RIS = 5 |

RIS superior to OLZ for PANSS |

| Jeste et al. [43], 2004 | RCT | USA Israel Poland Norway Netherlands Austria |

OLZ (88) RIS (87) |

8 | OLZ = 10 RIS = 2 |

OLZ no different from RIS for PANSS |

| Lindenmayer et al. [40], 2004 | Post-hoc analysis of an RCT | USA | OLZ (39) CLZ (40) RIS (41) HAL (37) |

14 | OLZ = 10−40 CLZ = 200−800 RIS = 4−16 HAL = 10−30 |

OLZ, CLZ, RIS superior to HAL for PANSS |

| Ascher-Svanum et al. [37], 2005 | Post-hoc analysis of an RCT | International, conducted in 17 countries | OLZ (1,337) HAL (659) |

6 | OLZ = 13 HAL= 12 |

OLZ superior to HAL for BPRS |

| Wang et al. [41], 2006 | RCT | USA | OLZ (17) RIS (19) |

16−17.7 | OLZ = 15 RIS = 5 |

RIS superior to OLZ for PANSS |

RCT, randomized controlled trial; OLZ, olanzapine; HAL, haloperidol; RIS, risperidone; PLC, placebo; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of information through the different phases of the review. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; dbRCTs, double blind randomized controlled trials.

Table 3.

Cochrane’s classification for risk of bias

| Source | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other source of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tollefson et al. [38], 1998 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Davis and Chen [36], 2001 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Conley and Mahmoud [42], 2001 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Jeste et al. [43], 2004 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Lindenmayer et al. [40], 2004 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ascher-Svanum et al. [37], 2005 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wang et al. [41], 2006 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

RESULTS

We have selected and included studies (3 with primary data analysis, 4 with secondary data analysis) on the use of olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia (Table 2). The most extensive study, a post hoc study of four RCTs [32-35], reported that olanzapine at a dosage ranging from 1 to 20 mg showed a major response than haloperidol (10−20 mg) in reducing anxiety symptoms measured with Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [36]. Three other post hoc studies showed a similar results: in a post hoc of a multicenter RCT [35] olanzapine at a dose ranging between 5 and 20 mg was superior to haloperidol (5−20 mg) in improving anxiety symptoms measured at BPRS [37]; the other post hoc study, using data of a multicenter RCT [32], demonstrated that olanzapine at a dose ranging between 7.5 and 17.5 mg was superior to haloperidol (10−20 mg) and placebo in improving anxiety symptoms measured at BPRS [38]. Finally, Lindenmayer and colleagues, in a post hoc study based on data from a multicenter RCT [39] showed that olanzapine, like risperidone and clozapine, was superior to haloperidol in improving positive, cognitive, and depression/anxiety PANSS domains [40]. Three RCTs compared olanzapine versus risperidone: in two of them [41,42], risperidone at mean dosage of 5 mg achieved a greater improvement than olanzapine 12 and 15 mg respectively in anxiety/depres-sion item of PANSS although in one study the sample size was fewer than 50 subjects [41]; in the other one there were no significant differences between olanzapine 10 mg and risperidone 2 mg in reducing anxiety symptoms measured with PANSS [43].

Reported Adverse Effects

Adverse effects were not systematically evaluated. Two studies did not collect the presence of side effects [37,40]. Olanzapine was associated with a lower incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms than haloperidol in 2 studies [36,38], while mixed results were seen in studies comparing olanzapine and risperidone [42,43]. Akathisia was investigated in one study, a lower incidence was found in the olanzapine group with respect to the haloperidol group [36]. Dry mouth was found to be more related to olanzapine than risperidone [42].

DISCUSSION

Results from this systematic review reported a higher efficacy of olanzapine over haloperidol on anxiety dimen-sion of schizophrenia. In two studies it was inferior to risperidone, while in two others there was no significant difference. However, studies comparing olanzapine to risperidone are low-powered due to an inadequate sample size. Instead, 2 of 3 studies comparing olanzapine to haloperidol have a sample with more than one thousand patients (Table 2). Overall, the side effect profile appears better than haloperidol. Except for clozapine, antipsy-chotics do not show substantial differences in improving nuclear symptoms of schizophrenia [44]. However, there are differences between the various antipsychotics when comparing other psychopathological dimensions, for which a different receptor profile determines a different clinical effect [45]. Olanzapine, a thienobenzodiazepine derivative, is a second generation (atypical) antipsychotic agent which has proven efficacy against the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Compared with first generation antipsychotics, it has greater affinity for serotonin 5-HT2A than for dopamine D2 receptors [46]. Olanzapine is characterized by antagonism for D2 receptors as well as for H1, 5HT-2a, 5HT2c and alpha1 receptors. The antagonism of H1, 5HT-2a, 5HT2c, alpha1 and M1 receptors could be the pharmacodynamic mechanism underlying the anti-anxiety properties of olanzapine [45,47-50] as shown in several preclinical models: i) 5HT-2a antagonist activity decreases anxiety potentially through 5-HT2A downregulation in the frontal cortex and in the hippocampus [51]; ii) Dorsal Raphe 5-HT2C antagonist activity prevents anxiety-like behavior through attenuation of increased GABAergic activity [52]; iii) H1 antagonistic activity reduces anxiety by potentially decreasing adrenergic neuron activation and modulation acetylcholine release [53]; iv) the alpha1 adrenoceptor antagonism attenuates anxiety-like behavior potentially due to reduction of excessive norepinephrine activity, in line with the noradrenergic theory of anxiety [54,55]; v) the M1 antagonism may ameliorate anxiety by blocking postsynaptic M1 receptors in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, in line with the cholinergic theory of anxiety [56]. Another possible hypothesis is linked to the ability to regulate the glutamatergic system. It is known that the dysfunction of the glutamatergic system is associated with numerous psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, depression and anxiety disorders [57]. Long term administration of olanzapine increases allopregnanolone (that can reduce the release of glutamate) in the rat cerebral cortex and hippocampus [58,59], increases D-aspartate and extracellular L-glutamate in the prefrontal cortex of the mouse [60], induces a down-regulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the caudate and medial and lateral putamen (CPu) and an increase in a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors in the same areas and a reduction of NMDA receptors in the hippocampal regions CA1 and CA3 [61]. On the clinical side, the improvement in anxiety symptoms given by olanzapine could be mediated either by a direct anxiolytic effect or indirectly by its efficacy on nuclear symptoms of schizophrenia. Anxiety at the onset of psychosis is central to the neuropsychological account of the condition, and arousal is implicated in the formation of delusional beliefs [62] and could also be a part of the premorbid personality of those patients and this in turn could be the result of the same neurodevelopmental process that may lie behind the emergence of schizophrenia [63]. Interesting, it was observed a shared genetic vulnerability for schizophrenia and anxiety disorder, consideration supporting the hypotheses according to which anxiety can be considered (in some degree) an epiphenomenon surging from an underlying psychotic disorder, rather than a true comorbid disorder and thus should not be diagnosed and treated separately [64]. Nevertheless, it is not clear whether the observed superiority is independent of its reduced liability to produce akathisia (which may look like anxiety) or its intrinsic anxiolytic effect [5,65]. Moreover, psychometric tools used to measure anxiety do not make it possible to discriminate between anxiety as a primary phenomenon and anxiety as secondary response to psychotic symptoms [66,67], nor differentiate “Anxiety” from “Angst” (German translation of “Anguish”) [68]. Additional studies having as primary outcome anxiety dimension and more appropriate assessment scales are needed to clarify the issue.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, data on anxiety were a secondary outcome in all studies and were extracted by different measures (PANSS and BPRS); Second, these measures of anxiety do not differentiate between primary and secondary anxiety, third, a post hoc study [36] shares a portion of the total sample with two other post hoc studies [37,38]. In addition, we included only studies with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or mixed samples of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Finally, the antianxiety effect of the other atypical antipsychotics was not investigated in our review.

CONCLUSIONS

Olanzapine has demonstrated superior efficacy over placebo and haloperidol in the included RCTs. There are two studies in which it was lower than risperidone while in two studies there were no significant differences with risperidone. Anxiety was a secondary outcome measure in most of the considered studies. Further research involving comparative effectiveness studies between typical and atypical antipsychotics, studies concerning the augmentation of antipsychotics with other non-antipsychotic compounds is needed to establish the most effective treatment strategies.

Footnotes

Funding

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Calogero Crapanzano. Supervision: Chiara Amendola. Writing-original draft: Calogero Crapanzano. Writing review & Editing: Ilaria Casolaro, Stefano Damiani.

References

- 1.Kaneko Y, Keshavan M. Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2012;10:125–135. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JJ, Pae CU, Han C, Bahk WM, Lee SJ, Patkar AA, et al. Exploring hidden issues in the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Clin Psycho-pharmacol Neurosci. 2021;19:600–609. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2021.19.4.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg H, Kumar S, Singh S, Kumar N, Verma R. New onset obsessive compulsive disorder following high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for treatment of negative symptoms in a patient with schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17:443–445. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2019.17.3.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pincus HA, Tew JD, First MB. Psychiatric comorbidity: is more less? World Psychiatry. 2004;3:18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temmingh H, Stein DJ. Anxiety in patients with schizophrenia: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:819–832. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tien AY, Eaton WW. Psychopathologic precursors and sociodemographic risk factors for the schizophrenia syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:37–46. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820010037005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howells FM, Kingdon DG, Baldwin DS. Current and potential pharmacological and psychosocial interventions for anxiety symptoms and disorders in patients with schizophrenia: structured review. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32:e2628. doi: 10.1002/hup.2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podea DM, Sabau AI, Wild KJ. Comorbid anxiety in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. In: Durbano F, editor. A fresh look at anxiety disorders. IntechOpen; London: 2015. pp. 131–144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braga RJ, Reynolds GP, Siris SG. Anxiety comorbidity in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig T, Hwang MY, Bromet EJ. Obsessive-compulsive and panic symptoms in patients with first-admission psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:592–598. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lysaker PH, Salyers MP. Anxiety symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: associations with social function, positive and negative symptoms, hope and trauma history. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:290–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Saez Fonseca JA, Huxley A. Insight, global functioning and psychopathology amongst in-patient clients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 2009;80:155–165. doi: 10.1007/s11126-009-9103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiffen BD, Rabinowitz J, Lex A, David AS. Correlates, change and 'state or trait' properties of insight in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;122:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goff DC, Freudenreich O, Evins AE. Augmentation strategies in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2001;6:904, 907–11. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900000961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritsner MS, Miodownik C, Ratner Y, Shleifer T, Mar M, Pintov L, et al. L-theanine relieves positive, activation, and anxiety symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled, 2-center study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:34–42. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05324gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blessing EM, Steenkamp MM, Manzanares J, Marmar CR. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for anxiety disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12:825–836. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Englisch S, Esser A, Enning F, Hohmann S, Schanz H, Zink M. Augmentation with pregabalin in schizophrenia. J Clin Psycho-pharmacol. 2010;30:437–440. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181e5c095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:383–402. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novick D, Montgomery W, Treuer T, Moneta MV, Haro JM. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotics for the treatment of negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50:56–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-112818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Littrell KH, Petty RG, Hilligoss NM, Kirshner CD, Johnson CG. The effect of olanzapine on anxiety among patients with schizophrenia: preliminary findings. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:523–525. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000088918.02635.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mauri MC, Colasanti A, Rossattini M, Moliterno D, Baldi ML, Papa P. A single-blind, randomized comparison of olanzapine at a starting dose of 5 mg versus 20 mg in acute schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29:126–131. doi: 10.1097/01.WNF.0000220819.71231.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirota P, Pannet I, Koren A, Tchernichovsky E. Quetiapine versus olanzapine for the treatment of negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:227–234. doi: 10.1002/hup.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tollefson GD, Sanger TM. Anxious-depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: a new treatment target for pharmacotherapy? Schizophr Res. 1999;35(Suppl):S13–S21. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(98)00164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dossenbach M, Jakovljevicz M, Folnegovic V, Uglesic B, Dodig G, Friedel P, et al. Olanzapine versus fluphenazine-6 weeks treatment of anxiety symptoms during acute schizo-phrenia. Schizophr Res. 1998;29:203. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)88822-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofer A, Rettenbacher MA, Edlinger M, Huber R, Bodner T, Kemmler G, et al. Outcomes in schizophrenia outpatients treated with amisulpride or olanzapine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2007;40:1–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-958520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen SA, Rosebush PI, Anglin RE, Mazurek MF. The predictive value of early treatment response in antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis: haloperidol versus olanzapine. Psychiatry Res. 2016;241:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacchetti E, Valsecchi P, Parrinello G QUERISOLA Group, author. A randomized, flexible-dose, quasi-naturalistic comparison of quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine in the short-term treatment of schizophrenia: the QUERISOLA trial. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strous RD, Kupchik M, Roitman S, Schwartz S, Gonen N, Mester R, et al. Comparison between risperidone, olanzapine, and clozapine in the management of chronic schizophrenia: a naturalistic prospective 12-week observational study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:235–243. doi: 10.1002/hup.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beasley CM, Jr, Tollefson G, Tran P, Satterlee W, Sanger T, Hamilton S. Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: acute phase results of the North American double-blind olanzapine trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:111–123. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00069-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beasley CM, Jr, Sanger T, Satterlee W, Tollefson G, Tran P, Hamilton S. Olanzapine versus placebo: results of a double-blind, fixed-dose olanzapine trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:159–167. doi: 10.1007/BF02245617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beasley CM, Jr, Hamilton SH, Crawford AM, Dellva MA, Tollefson GD, Tran PV, et al. Olanzapine versus haloperidol: acute phase results of the international double-blind olanzapine trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997;7:125–137. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(96)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tollefson GD, Beasley CM, Jr, Tran PV, Street JS, Krueger JA, Tamura RN, et al. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:457–465. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis JM, Chen N. The effects of olanzapine on the 5 dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American and international trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:757–771. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v62n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ascher-Svanum H, Stensland M, Zhao Z, Kinon BJ. Acute weight gain, gender, and therapeutic response to antipsychotics in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tollefson GD, Sanger TM, Beasley CM, Tran PV. A double-blind, controlled comparison of the novel antipsychotic olanzapine versus haloperidol or placebo on anxious and depressive symptoms accompanying schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43:803–810. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:255–262. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.255. Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Lieberman JA, Citrome L, Sheitman B, et al. Effects of atypical antipsychotics on the syndromal profile in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:551–556. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Savage R, Borisov A, Rosenberg J, Woolwine B, Tucker M, et al. Efficacy of risperidone versus olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia previously on chronic conventional antipsychotic therapy: a switch study. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conley RR, Mahmoud R. A randomized double-blind study of risperidone and olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:765–774. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.765. Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeste DV, Barak Y, Madhusoodanan S, Grossman F, Gharabawi G. International multisite double-blind trial of the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and olanzapine in 175 elderly patients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:638–647. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200311000-00008. Erratum in: Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004; 12:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:951–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. Erratum in: Lancet 2013;382:940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crapanzano C, Damiani S, Guiot C. Quetiapine in the anxiety dimension of mood disorders: a systematic review of the literature to support clinical practice. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;41:436–449. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhana N, Foster RH, Olney R, Plosker GL. Olanzapine: an updated review of its use in the management of schizophrenia. Drugs. 2001;61:111–161. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bymaster FP, Calligaro DO, Falcone JF, Marsh RD, Moore NA, Tye NC, et al. Radioreceptor binding profile of the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00129-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crapanzano C, Amendola C, Politano A, Laurenzi PF, Casolaro I. Olanzapine for the treatment of somatic symptom disorder: biobehavioral processes and clinical implications. Psychosom Med. 2022;84:393–395. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000001052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crapanzano C, Amendola A, Conigliaro C, Casolaro I. Clothiapine: highlights on pharmacological and clinical profile of an undervalued drug. Swiss Arch Neurol Psychiatry Psychother. 2022;173:w10065 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crapanzano C, Laurenzi PF, Amendola C, Casolaro I. Clinical perspective on antipsychotic receptor binding affinities. Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43:680–681. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2021-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen H. Anxiolytic effect and memory improvement in rats by antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A precursor protein. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22:84–93. doi: 10.1002/da.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Craige CP, Lewandowski S, Kirby LG, Unterwald EM. Dorsal raphe 5-HT(2C) receptor and GABA networks regulate anxiety produced by cocaine withdrawal. Neuropharmacology. 2015;93:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serafim KR, Kishi MS, Canto-de-Souza A, Mattioli R. H1 but not H2 histamine antagonist receptors mediate anxiety-related behaviors and emotional memory deficit in mice subjected to elevated plus-maze testing. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46:440–446. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okuyama S, Sakagawa T, Chaki S, Imagawa Y, Ichiki T, Inagami T. Anxiety-like behavior in mice lacking the angiotensin II type-2 receptor. Brain Res. 1999;821:150–159. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ketenci S, Acet NG, Sarıdoğan GE, Aydın B, Cabadak H, Gören MZ. The neurochemical effects of prazosin treatment on fear circuitry in a rat traumatic stress model. Clin Psycho-pharmacol Neurosci. 2020;18:219–230. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2020.18.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wall PM, Flinn J, Messier C. Infralimbic muscarinic M1 receptors modulate anxiety-like behaviour and spontaneous working memory in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;155:58–68. doi: 10.1007/s002130000671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Javitt DC. Glutamate as a therapeutic target in psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:984–997. 979. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang Y, Hsieh HL, Huang SK, Wang SJ. Neurosteroid allopregnanolone inhibits glutamate release from rat cerebrocortical nerve terminals. Synapse. 2019;73:e22076. doi: 10.1002/syn.22076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mead A, Li M, Kapur S. Clozapine and olanzapine exhibit an intrinsic anxiolytic property in two conditioned fear paradigms: contrast with haloperidol and chlordiazepoxide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sacchi S, Novellis V, Paolone G, Nuzzo T, Iannotta M, Belardo C, et al. Olanzapine, but not clozapine, increases glutamate release in the prefrontal cortex of freely moving mice by inhibiting D-aspartate oxidase activity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46288. doi: 10.1038/srep46288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tarazi FI, Baldessarini RJ, Kula NS, Zhang K. Long-term effects of olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine on ionotropic glutamate receptor types: implications for antipsychotic drug treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:1145–1151. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kiran C, Chaudhury S. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2016;25:35–40. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.196045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davies N, Russell A, Jones P, Murray RM. Which characteristics of schizophrenia predate psychosis? J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:121–131. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3956(97)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohi K, Otowa T, Shimada M, Sasaki T, Tanii H. Shared genetic etiology between anxiety disorders and psychiatric and related intermediate phenotypes. Psychol Med. 2020;50:692–704. doi: 10.1017/S003329171900059X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pringsheim T, Gardner D, Addington D, Martino D, Morgante F, Ricciardi L, et al. The assessment and treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63:719–729. doi: 10.1177/0706743718760288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grillo L. A possible link between anxiety and schizophrenia and a possible role of anhedonia. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2018;2018:5917475. doi: 10.1155/2018/5917475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carter DM, Mackinnon A, Copolov DL. Patients' strategies for coping with auditory hallucinations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:159–164. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gentil V, Gentil ML. Why anguish? J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:146–147. doi: 10.1177/0269881109354134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]