Abstract

Objective

To provide insights into women’s attitudes towards a human papillomavirus (HPV)-based cervical cancer screening strategy.

Data sources

Medline, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, CINAHL and ClinicalTrials.gov were systematically searched for published and ongoing studies (last search conducted in August 2021).

Methods of study selection

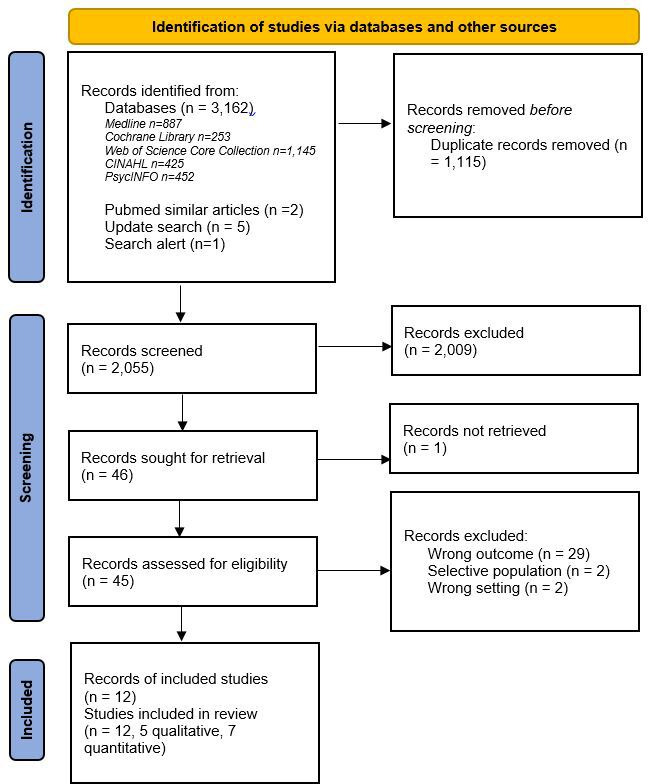

The search identified 3162 references. Qualitative and quantitative studies dealing with women’s attitudes towards, and acceptance of, an HPV-based cervical cancer screening strategy in Western healthcare systems were included. For data analysis, thematic analysis was used and synthesised findings were presented descriptively.

Tabulation, integration, and results

Twelve studies (including 9928 women) from USA, Canada, UK and Australia met the inclusion criteria. Women’s attitudes towards HPV-based screening strategies were mainly affected by the understanding of (i) the personal risk of an HPV infection, (ii) the implication of a positive finding and (iii) the overall screening purpose. Women who considered their personal risk of HPV to be low and women who feared negative implications of a positive finding were more likely to express negative attitudes, whereas positive attitudes were particularly expressed by women understanding the screening purpose. Overall acceptance of an HPV-based screening strategy ranged between 13% and 84%.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides insights into the attitudes towards HPV-based cervical cancer screening and its acceptability based on studies conducted with women from USA, Canada, UK and Australia. This knowledge is essential for the development of education and information strategies to support the implementation of HPV-based cervical cancer screening.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO (CRD42020178957).

Keywords: papillomaviridae

Key messages.

What is already known on this topic

Changing cervical cancer screening from cytology to HPV-based screening could influence the acceptability and thus the overall success of screening programmes. Understanding women’s attitudes towards an HPV-based screening strategy is therefore essential for the development of successful screening and implementation strategies.

What this study adds

Women with negative attitudes towards HPV-based screening particularly fear that being tested for a sexually transmitted infection may lead to stigmatisation. On the other hand, women with positive attitudes value the advantages of (potential) detection of earlier disease and a lower test frequency.

How this study might impact research, practice or policy

Introducing HPV-based screening requires women-centred education focusing on the aetiology and risk factors of cervical cancer. Broader knowledge of the benefits and harms of such a screening strategy may help to reduce psychological distress associated with testing for an infection that is mainly sexually transmitted.

Introduction

Of all malignant tumours, cervical cancer is the one that can best be prevented by screening.1–3 For many years, cervical cancer screening has been based on cytological testing (ie, the Pap test) for the early detection of cellular changes associated with precancerous cervical lesions. These cellular changes can be triggered by human papillomavirus (HPV)—in particular, some ‘high-risk’ types like HPV types 16 and 18. Newer, high certainty evidence has established the effectiveness of cervical cancer screening strategies based on the detection of HPV.4 5 Women who tested positive for high-risk HPV are referred to cytology testing for the early detection and treatment of cellular changes, if necessary. Women who test HPV-negative, on the other hand, are not at a higher risk of developing precancerous lesions—at least not within the next 3 to 5 years.

While several countries worldwide (including Australia,6 the Netherlands7 and UK8) have already implemented HPV-based cervical cancer screening with cytology triage, others are still preparing the implementation.9 An HPV-based screening strategy with cytology triage involves follow-up cytological examinations only for those women with a positive HPV test. Changing cervical cancer screening from cytology to HPV-based screening could influence the acceptability and thus overall success of the screening programme, because some HPV-based screening regimens offer the option of self-sampling and screenings are recommended less frequently than with cytology testing.10

Understanding women’s views and experiences—particularly when screened for a cancer-causing sexually transmitted infection—may improve successful implementation of, and adherence to, screening strategies.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis examining women’s attitudes towards an HPV-based screening strategy for prevention of cervical cancer.

Methods

We adhered to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) statement.11

This review is part of a Health Technology Assessment, including also a clinical effectiveness and health economic assessment, for which the protocol was registered a priori in PROSPERO (CRD42020178957). Compared with the protocol registered in PROSPERO, which focused on the assessment of clinical effectiveness, the approach for this review was modified (see methods below for specifications).

Comprehensive systematic literature searches for relevant studies were conducted following the recommendation of PRESS (Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies).12 We searched Medline, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO and CINAHL (initial searches took place in November 2019 and an update search in Medline was performed in August 2021). The search strategy for the clinical effectiveness domain of the Health Technology Assessment was adapted and combined with additional search terms designed to identify studies examining preferences and attitudes. The Medline search strategy of the current review is displayed in the supplemental material S1. Search strategies for the other databases were adapted from the Medline strategy. We did not apply study filters for study designs as filters may exclude relevant studies dealing with our research question.13 We also did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches. Searches for ongoing or unpublished but completed studies were performed in ClinicalTrials.gov.14 We used relevant studies and/or systematic reviews to search for additional references via PubMed using the ‘similar articles function’15 and forward citation tracking using the Web of Science Core Collection. Reference lists of eligible studies and systematic reviews were reviewed to identify any other studies that might not have been retrieved by the electronic searches.

The titles and abstracts of the identified references were independently screened by two reviewers (CS, JN), and full texts of all potentially relevant articles were obtained. Full-text screening was also conducted independently (by the same two reviewers) and reasons for exclusions were documented. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus. The complete screening process was conducted in Covidence.16

Study selection

We included qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods studies focusing on asymptomatic women close to or within the age range suitable for cervical cancer screening in Western countries—that is, 25 to 65 years.17

Studies examining the attitudes of women who were not representative of women eligible for standard screening procedures18 were not of interest. Therefore, studies on women with a high risk of cervical cancer (eg, due to a compromised immune system), with known cytological abnormalities, cervical cancer or a total or radical hysterectomy were excluded.

Furthermore, we included only studies that were conducted in high-income countries (Human Development Index>0.88; European Economic Area countries, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, USA and Canada) for better applicability to Western settings.19 20 Review articles, case reports and results reported solely in abstract form as well as work that was not peer reviewed were excluded.

Phenomena of interest

Our phenomena of interest were both attitudes towards, and acceptance of, HPV-based cervical cancer screening. In women eligible for cervical cancer screening the primary HPV testing could be used in two different screening strategies—either as a stand-alone test or followed by cytology in those women with a positive HPV test. ‘Attitudes’ were defined as thoughts and feelings that might or might not be reflected in a particular behaviour. ‘Acceptance’ was defined as a tendency to follow an HPV-based screening guideline. We did not consider studies focusing on co-testing (using HPV testing in combination with cytology), or studies addressing preferences and/or attitudes related to the acceptance of cervical cancer screening in general (in terms of ‘should I go for screening?’). These questions have been evaluated before.21 22 We also excluded studies addressing: preferences of caregivers, family members and healthcare professionals, information needs, factors related to screening acceptance, preferences towards HPV vaccines or prolonged screening intervals.

Extraction of data

We extracted study characteristics (eg, author and study country, year of publication, data collection methods used and number of participants), characteristics of the study population (eg, age range, ethnicities) and the attitudes towards HPV-based screening, including acceptance rates. Data from each study were extracted by one reviewer (JN) and checked by a second (CS).

Quality assessment

We evaluated the risk of bias and applicability of results using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).23 24 Again, two reviewers (JN, CS) independently assessed study quality. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Synthesis of findings

Data on women’s attitudes towards, and acceptance of, HPV-based screening were analysed separately. For the qualitative data on attitudes towards HPV-based screening, we applied a thematic analysis (using inductive coding) and descriptive presentation of the synthesised findings. Data analysis was an iterative process and started with familiarisation and extraction of the data. Text sections, including descriptions of themes and categories offered by the study authors as well as exemplary comments by study participants, were analysed and manually coded. First, one reviewer (JN) read through the text about three to five times to familiarise herself with the data and then independently extracted any data that reflected attitudes towards HPV-based screening. Then, the same reviewer manually coded any extracted qualitative data related to women’s attitudes towards HPV-based screening using the codes (i) positive, (ii) neutral, (iii) negative attitudes. Both steps were checked by the second reviewer (CS) and any conflicts were resolved by discussion. Finally, categories related to women’s attitudes towards HPV-based screening were defined based on the findings of the primary studies.25

The quantitative data on the acceptance of HPV-based screening and the categories (positive, neutral and negative attitudes towards HPV-based screening) emerging from the qualitative analysis were summarised descriptively. We summarised the questions, keeping to the original wording as closely as possible, alongside with the responses and their distribution. A meta-analysis across studies was not possible due to heterogeneity of the data and findings.

Results

The searches identified 3170 citations, including 1115 duplicates. Among the 2055 unique records screened, 2009 were excluded based on title and abstract (eg, wrong setting, no focus on HPV testing, clinical studies, editorials), and 45 were considered for full-text screening. Of these, twelve studies were included (five qualitative studies, seven quantitative studies). Thirty-three studies did not meet the eligibility criteria and were excluded (eg, the outcome of interest was not addressed, the population did not represent the general screening population, or the setting did not meet our inclusion criteria). Studies that were excluded at full-text screening are cited in the supplemental material S2.

The detailed study selection process is presented in figure 1. A search in ClinicalTrials.gov (date of the search: 11 August 2021) identified no relevant ongoing studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) flow chart11.

Key study characteristics are summarised in table 1. In brief, three qualitative studies were conducted in the United Kingdom26–28 and two in Australia.29 30 Of the seven quantitative studies, six were conducted in the USA31–36 and one in Canada.37 In total, 231 women were included across the qualitative studies (ranging from 14 to 74 women per study), and 9697 women were considered in the quantitative studies (ranging from 199 to 5532 women per study). The women’s age varied between 16 and >65 years and mixed populations (ie, women with ethnically diverse backgrounds including White, South Asian, African Caribbean/American and Hispanic) were recruited across the studies.

Table 1.

Key study characteristics of the included studies

| Author, year/country | Data collection | Study Start (m/y)–end (m/y) |

N (women) | Age range (y) | Ethnicity | Study population | Phenomena of interest |

| Qualitative study design | |||||||

| Dodd, 2020/ Australia29 | Semistructured interviews | 12/18–12/18 | 26 | <35–>66 | 22/26 Born in Australia 4/26 Not born in Australia |

|

Understanding the screening purpose |

| McCaffery, 2003/UK26 | Focus group discussions | 07/00–09/00 | 71 | 20–59 | 16/71 African-Caribbean 19/71 Indian 20/71 Pakistani 16/71 White British 41/71 Not born in UK |

|

Understanding the implication of a positive finding; understanding the screening purpose |

| McCaffery, 2006/ England27 | In-depth interviews | 06/01-12/03 | 74 | 20–64 | 41/74 White British 17/74 South Asian 16/74 African Caribbean |

|

Understanding the implication of a positive finding; understanding the screening purpose |

| Nagendiram, 2020/ Australia30 | Semistructured interviews | 03/19–04/19 | 14 | 20–58 | No information provided |

|

Understanding the screening purpose |

| Patel, 2018/ England28 | Semistructured interviews, focus group discussions | 04/15–12/16 | 46 | 25–65 | 20/46 White British 26/46 White Eastern European |

|

Understanding the personal risk; understanding the implication of a positive finding; understanding the screening purpose |

| Quantitative study design (observational) | |||||||

| Gerend, 2017/ USA32 | Online questionnaire via mail | 2014 | 313 | 21–65 | 59/313 Non-white 250/313 White 38/313 Hispanic/Latina ethnicity |

|

Acceptance |

| Jayasinghe, 2016/ Australia36 | Online questionnaire | 02/14–03/14 | 199 | 16–28 | 118/199 Born in Australia |

|

Acceptance |

| Ogilvie, 2013/ Canada34 | Online questionnaire | 05/11–09/11 | 981 | 25–65 | 81/981 Chinese 24/981 Aboriginal 876/981 Caucasian and other |

|

Acceptance |

| Saraiya, 2018/ USA33 | Online questionnaire | 09/15 | 1309 | 18–>65 | 997/1309 White 124/1309 Black 131/1309 Hispanic 57/1309 Other |

|

Acceptance |

| Silver, 2015/ USA31 | Interviewer-administered survey | 03/08–03/11 | 551 | 36–62 | 420/551 White 91/551 Black 40/551 Other |

|

Understanding the screening purpose |

| Smith, 2021/ Canada37 | Online questionnaire | 08/17–02/18 | 5532 | 25–65 | No detailed information provided (reflects the North American population) |

|

Acceptance; understanding the implication of a positive finding; understanding the screening purpose |

| Thompson, 2020/ USA35 | Online questionnaire | 2018 | 812 | 30–65 | 187/812 Black/African American 553/812 White/Caucasian 151/812 Hispanic/Latina |

|

Acceptance; understanding the screening purpose |

CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV, Human papillomavirus; m, month; y, year(s).

The qualitative studies provided insights into women’s attitudes towards HPV-based screening using in-depth interviews,27 focus group discussions,26 28 and semistructured interviews.28–30 The quantitative studies addressed both women’s attitudes towards HPV-based screening (n=3) and/or the acceptance of HPV-based compared with cytology-based screening (n=6) using an interviewer-administered survey or online questionnaires.31–37

Two studies31 32 focused on co-testing (concurrent HPV testing and cytology, which is not the focus of our review). However, in these studies, we could extract data on the attitudes of women towards the idea of completely replacing the Pap test with primary HPV testing, which is why we decided to include them.

Phenomena of interest

Based on the thematic synthesis approach the positive, negative or neutral attitudes of women related to different aspects of HPV screening or the women’s (mis-)conceptions of it could be identified. The studies identified reported the women’s attitudes in relation to the screening purpose,26–31 35 37 the implications of a positive finding26–28 37 and the personal risk of being infected.28 31 Furthermore, acceptance of an HPV-based screening programme (table 2) was described in terms of willingness to undergo screening.32–37

Table 2.

Results of the quantitative studies that assessed acceptance of, and/or attitudes towards, HPV-based screening

| Author | Phenomena of interest | Questionnaire items used to assess acceptance and/or attitudes | Answers provided by the women (N/N total) |

| Gerend, 201732 | Acceptance | ‘If your doctor or healthcare provider recommended it, would you agree to have this new HPV test done instead of a Pap test?’ | Yes: 55% (172*/313) No: 14% (44*/313) Undecided: 31% (97*/313) |

| Jayasinghe, 201636 | Acceptance | ‘I would be willing to have an HPV test to screen for cervical cancer instead of a Pap smear.’ | Yes 79% (106/135) |

| Willingness to screen with HPV testing at extended screening intervals | 3 Yearly: 61% (82/135) 5 Yearly: 31% (41/134) 10 Yearly: 10% (14/134) |

||

| Ogilvie, 201334 | Acceptance | ‘I would be willing to have an HPV test to screen for cervical cancer instead of a Pap smear’ (7-point Likert scale; >4 coded as ‘intending to screen’) | 84% (826/981) intended to screen |

| Saraiya, 201833 | Acceptance | ‘Which of the following cervical cancer screening options would be acceptable to you if your doctor recommended it for you?’ | HPV test alone once every 3 years: 13% (172/1309) Annual Pap test: 40% (520/1309) Pap test every 3 years: 25% (326/1309) Pap test with HPV test every 3 years: 33% (433/1309) Pap test with HPV test every 5 years: 15% (198/1309) None of the options: 15% (190/1309) |

| Silver, 201531 | Understanding the screening purpose | Screening test preference | HPV Only: 8% (43/549) Pap Only: 61% (333/549) Either: 32% (173/549) |

| ‘If HPV test only, how much concern about not having a Pap smear?’ | None: 22% (120/548) Slight: 37% (201/548) Moderate: 30% (165/548) Severe: 11% (62/548) |

||

| ‘Which is more concerning’ | Abnormal Pap: 27% (146/550) HPV Positive: 9% (51/550) Equally concerning: 64% (353/550) |

||

| Understanding the personal risk |

'Perceived risk of HPV' |

None/Low: 90% (492/549) Moderate/High: 10% (57/549) |

|

| Smith, 202137 | Acceptance | ‘Having an HPV test instead of a Pap to screen for cervical cancer is acceptable to me’ | Strongly agree/ agree: 63% (3342/5336) Neutral: 16% Disagree: 11% Don’t know: 10% |

| ‘Receiving HPV testing starting at age 30 years is acceptable to me’ | Agree: 68% (3635/5336 total sample); 81% (2691/3342 women who would accept HPV screening) Disagree: 13% (682/5336 total sample); 8% (259/3342 women who would accept HPV screening) Neutral: 18% (981/5336 total sample); 11% (373/3342 women who would accept HPV screening) |

||

| ‘I would be willing to have an HPV test every 4–5 years instead of a Pap every 3 years’ | Agree: 54% (2858/5336 total sample); 74% (2472/3342 women who would accept HPV screening) Disagree: 21% (1096/5336 total sample); 11% (352/3342 women who would accept HPV screening) Neutral: 25% (1353/5336 total sample); 15% (506/3342 women who would accept HPV screening) |

||

| Understanding the implication of a positive finding | ‘I think people would judge me for having HPV’ | Agree: 33% (1775/5336) Disagree: 27% (1419/5336) Neutral: 31% (1666/5336) |

|

| ‘Having HPV would not cause me any concern about cervical cancer’ | Agree: 3% (181/5336) Disagree: 77% (4,112/5336) Neutral: 11% (569/5336) |

||

| ‘I would feel comfortable telling my partner if I had HPV’ | Agree: 64% (3391/536) Disagree: 13% (709/5336) Neutral: 14% (755/5336) |

||

| ‘Being HPV positive would not affect my relationship with my partner’ | Agree: 23% (1249/5336) Disagree: 38% (2003/5336) Neutral: 30% (1584/5336) |

||

| Understanding the screening purpose | ‘What would concern you more?’ | Abnormal Pap test result: 13% (668/5336) HPV positive test result: 13% (683/5336) Equally concerning: 72% (3855/5336) |

|

| Thompson, 202035 | Acceptance | Willingness to receive the HPV test instead of the Pap test (5-point Likert scale) | Willing: 55% (447/812) Not willing: 45% (365/812) |

| Understanding the screening purpose | ‘What worries you more’ | Abnormal HPV test: 11% (90/812) Abnormal pap test: 14% (114/812) Equally worrying: 60% (489/812) Neither: 15% (119/812) |

|

| HPV test benefit: Less time at doctor’s office | Yes: 74% (597/812) No: 26% (215/812) |

||

| HPV test benefit: Less frequent discomfort | Yes: 70% (571/812) No: 30% (241/812) |

*These numbers were calculated from the percentage and total number (N total * percentage).

HPV, Human Papillomavirus; n, number.

Understanding the personal risk

One quantitative study31 (Silver 2015) including 551 women (table 2) examined how understanding the personal risk for cervical cancer may influence decisions to undergo HPV-based screening. Approximately 90% (492/549) of participants assessed their risk of being infected with HPV as low or believed that due to their lifestyle they were not at risk of infection. These women felt therefore that HPV-based screening has little or no benefit for them. In the qualitative study of Patel et al 28 (table 3) some women claimed that an HPV test was not necessary due to their ‘safe and conservative’ lifestyle—for example, living in a monogamous relationship for years, living a strict religious life or having only one sexual partner.

Table 3.

Results of the qualitative studies that assessed attitudes towards HPV-based screening

| Reference | Phenomena of interest | Positive attitude (reported frequencies) |

Negative attitude (reported frequencies) |

Neutral attitude (reported frequencies) |

Reasons/answers provided by women |

| Dodd, 202029 | Understanding the screening purpose |

|

|

|

|

| McCaffery, 200326 | Understanding the implication of a positive finding; understanding the screening purpose |

|

|

|

|

| McCaffery, 200627 | Understanding the implication of a positive finding; understanding the screening purpose |

|

|

|

|

| Nagendiram, 202030 | Understanding the screening purpose |

|

|

|

|

| Patel, 201828 | Understanding the personal risk; understanding the implication of a positive finding; understanding the screening purpose |

|

|

|

|

HPV, human papillomavirus; NR, not reported.

Understanding the implication of a positive finding

HPV being a sexually transmitted infection also impacts women’s attitudes towards HPV-based screening26–28 37. In three qualitative studies (including 191 women26–28), some women (actual numbers not reported) were sceptical about an HPV-based screening strategy as an HPV infection is usually sexually transmitted (table 3). These women felt that testing for such an infection could lead to stigmatisation and that the test would convey negative messages to their partners, such as mistrust and infidelity. Particularly among women from cultures with strict Muslim or Catholic religious beliefs, being tested for a sexually transmitted infection has been associated with a wide range of issues, including fears of being accused of indecent behaviour by their families (table 3).26–28

The results of the quantitative study of Smith et al 37 revealed that 38% (2003/5336) of the included women feared that a positive test result would affect their relationship, and 33% (1775/5336) were concerned about their ‘public perception’, whereas 23% (1249/5336) and 27% (1419/5536) did not think that these issues would occur.

Understanding the screening purpose

Three studies including 5677 women revealed that, particularly, women who were aware of the screening purpose (ie, the association between an HPV infection and the risk of cervical cancer) had anxiety and distress when being confronted with a positive finding (tables 2 and 3).26 27 37 For example, most women (77%, 4112/5336) from the quantitative study of Smith et al 37 stated that they were stressed after receiving a positive HPV test result.

In Australia, where an HPV-based screening strategy was implemented in 2017,6 women who were better informed—that is, women who justified their attitudes in accordance with current evidence, particularly appreciated the early cancer prevention strategy and the option of prolonged screening intervals.29 30 Some women also stated that the introduction of HPV-based screening might increase the uptake of the HPV vaccination.29 Negative attitudes in these studies included concerns about the prolonged screening intervals and the older age recommended for the very first screening (25 years) compared with cytology-based screening.29 30 Furthermore, three other studies revealed that for the majority of women, an abnormal HPV test result would be as concerning as an abnormal cytology result (60%,35 489/812; 64%,31 353/550; 72%,37 3855/5336).

Overall the results of the qualitative studies26 28 29 indicated that women would be more open-minded about HPV-based screening if they—and also the people around them—were better informed about the benefits and harms of screening and if the offered screening test had been used more often.

Acceptance of HPV-based screening

Acceptance rates of HPV-based screening strategies were reported in six quantitative studies32–37 (table 2) and varied between 13%33 (172/1309) and 84%34 (826/981). Reasons for these variations were often related to the screening options offered. While in five studies, more than half of the participants were willing to receive an HPV test (as a ‘stand-alone’ test) instead of a Pap test (55%,35 447/812; 55%,32 172/313; 63%,37 3343/5336; 79%,36 157/199; 84%,34 826/981), one study33 reported a much lower acceptance rate (13%, 172/1309). However, not every woman accepting an HPV test as a stand-alone test would also accept other changes related to the screening procedure.37 A delayed starting age at 30 years would have been accepted by 81% (2691/3343) while prolonged screening intervals of 4 to 5 years either on their own or in combination with the delayed starting age at 30 years would have been accepted by 74% (2472/3343) of women.37 Similar results were found in the study of Jayasinghe et al.36 While an HPV test alone was accepted by 79% (106/135) of women, a lower proportion of women agreed with longer screening intervals of 3 years (ie, 61% (82/135), 5 years (31%), and 10 years (11%).

When different screening options were suggested,33 40% (520/1309) would accept an annual Pap test, 25% (326/1309) a Pap test every 3 years, and 13% (172/1309) an HPV test alone every 3 years.

Methodological quality

Overall, the methodological quality was high in the five qualitative studies26–30 (according to the MMAT,24 see table 4). Both data collection and data analyses, including interpretation, were sufficiently described. The methods used—that is, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and framework analysis to derive findings from the data, were appropriate. In contrast, the quantitative studies showed some methodological flaws. In two31 37 of the quantitative studies (see table 5) the study samples were not clearly described (both referred to another study), and ‘non-response” bias could not be excluded in one37 of the studies (only 38% of the original study population participated). Three studies32 33 35 recruited their participants through a US online panel that provides financial rewards for study participation, so selection bias was probably due to registration to the panel that was mandatory for study participation. In two of the studies,31 34 only women attending cervical cancer screening were recruited, which resulted in the exclusion of non-attenders. The methods used for data collection and analyses in the six quantitative studies addressing women’s acceptance of HPV-based screening32–37 were clearly described and appropriate (online questionnaires). However, the questions the participants were asked might be susceptible to response bias.38

Table 4.

Methodological quality of the included qualitative studies using the MMAT.24

| Is a clear research question defined? | Are the data fitting the research questions? | Is the qualitative approach appropriate? | Are data collection methods appropriate? | Are findings adequately derived from data? | Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | Is there sufficient coherence between data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | |

| Dodd, 202029 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Yes† | No‡ | Yes |

| McCaffery, 200326 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes§ | Yes† | Yes | Yes |

| McCaffery, 200627 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes¶ | Yes† | Yes | Yes |

| Nagendiram, 202030 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Yes** | Yes | Yes |

| Patel, 201828 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yesa | Yes† | Yes | Yes |

*Semistructured interviews.

†Framework analyses.

‡No information on frequencies of the attitudes were provided.

§Focus group discussion.

¶In-depth interviews.

**Thematic analyses.

MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Table 5.

Methodological quality of the included quantitative studies using the MMAT.24

| Is a clear research question defined? | Are the data fitting the research questions? | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address research question? | Is the sample representative of the target population? | Are the measurements appropriate? | Is the risk of non-response bias low? | Are the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | |

| Gerend, 201732 | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Cannot tell† | Yes‡ | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Jayasinghe, 201636 | Yes | Yes | Yes§ | No | Yes‡ | Yes | Yes |

| Ogilvie, 201334 | Yes | Yes | Yes§ | No¶ | Yes‡ | Yes | Yes |

| Saraiya, 201833 | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Cannot tell† | Yes‡ | Cannot tell | Yes |

| Silver, 201531 | Yes | Cannot tell | No§ | No¶ | Yes‡ | Yes | Yes |

| Smith, 202137 | Yes | Yes | Yes§ | Cannot tell | Yes‡ | No** | Yes |

| Thompson, 202035 | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Cannot tell† | Yes‡ | Yes | Yes |

*Participants were recruited through an online panel.

†Population was preselected for, for example, age, sex, ethnicity and region. Still, there was no chance of involving women who had, for example, no affinity with computers.

‡Questionnaires; the questions the participants were asked were susceptible to bias.38

§Population originally recruited for another study question (in a larger trial).

¶The original study sample consisted only of women who participated in cervical cancer screening. Non-attenders were not involved.

**<50% of the eligible women from the original study population participated (38%).37

MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool;

Discussion

Main results

We identified three categories of patients’ understanding reflecting their attitudes towards HPV-based screening. First, we found that some women underestimate their risk of being infected with HPV. While it is true that women who have never been sexually active rarely develop cervical cancer, any woman who has had at least one sexual partner is potentially at risk for HPV infection and cervical cancer39 and therefore should be screened regularly. Second, we found that some women fear negative consequences when receiving a positive test result. The qualitative studies showed that particularly women living in a conservative social environment experienced negative feelings and undesired reactions from their partners when confronted with a positive HPV test. Lastly, we found that especially women who understand the screening purpose and the underlying biological context are likely to accept the implementation of HPV-based screening. However, anxiety and distress related to a positive finding (concerning the presence of HPV and the risk of progressive cellular changes) were also reported in these samples.

The results from studies dealing with the overall acceptance of primary HPV-based screening varied. While in the USA the acceptance rates ranged between 13% and 55%, in Canada and Australia acceptance rates were higher, ranging from 63% to 84%. Particularly in countries with low(er) acceptance rates more thought should be put into the promotion and education of vaccine uptake for the prevention of HPV infections. Our systematic review also reveals that women who are not well informed about the benefits and harms of HPV-based cervical cancer screening expressed concerns about prolonged screening intervals. We therefore believe that women may be less concerned about new HPV-based screening guidelines and strategies if their implementation is guided by educational efforts that include the harms and benefits of extended screening intervals and that provide data on the diagnostic accuracy of self-sampled smears.40 41

Implications for practice

Negative attitudes reported in qualitative studies were often based on ‘wrong’ personal risk estimations of acquiring a sexually transmitted disease and the fear of testing positive for such a disease. Thus, an education strategy addressing both men and women is mandatory to increase acceptance.42 43 This strategy should include the risk factors for an HPV infection,44 the aetiology and risks of the infection—for example, HPV is a common45 and ‘longlasting’ virus which could be acquired years ago and recurrent infections are possible.46 This strategy should further explain changes in the screening procedure, including longer screening intervals and delayed age at first screening, and their consequences for the detection of cervical cancer.

Additionally, our systematic review revealed that for the majority of women in three of the included studies, an abnormal HPV test result would be as concerning as an abnormal cytology result.31 35 37 It seems that many women do not understand the meaning of an abnormal Pap test, which detects precancerous lesions, and the meaning of a positive HPV test, which refers to an increased risk of developing precancerous lesions.4 5 Therefore, information about the meaning of a positive HPV test and the prevalence of HPV among the population should also be included in education strategies.

Strength and limitations of this systematic review

This is the first systematic review synthesising women’s attitudes towards cervical cancer screening in Western countries, using both qualitative and quantitative data. It also provides a thorough overview of the complexities involved in women’s decision-making regarding cervical cancer screening. The available study pool allowed us to summarise a wide range of attitudes of women from different countries of the Western world (USA, Canada, Europe/UK and Australia) and from mostly multicultural backgrounds. Although the study samples varied (particularly in ethnicity, religion and age), the attitudes towards HPV-based screening were similar—except for women who were better educated—regarding the benefits and risks of HPV-based screening.

We explored heterogeneity by summarising the women’s attitudes using thematic synthesis,25 which allowed us to provide broader categories reflecting different views. The proportion of women providing an answer to the respective questions was not consistently reported by the study authors. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether ‘older’ studies26 27 adequately reflect the attitudes of the current screening populations—who may be more ‘informed’ by using different media. We considered only studies from high-income countries (Human Development Index >0.88) with organised screening programmes which are mostly, but not necessarily, linked to general gynaecological care.19 20

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that introducing HPV-based screening as a cervical cancer screening strategy requires women-centred education focusing on the aetiology and risk factors of cervical cancer. Broader knowledge of the benefits of an HPV-based screening strategy might further reduce psychological distress (eg, stigmatisation) associated with testing for an infection that is often sexually transmitted.

Footnotes

Contributors: JN and CS conceptualised the aim of this systematic review and designed the methodology. JN and CS were involved in screening and data extraction. JN, EN and CS were involved in data synthesis. JN prepared the original draft. EN, MRM, HR, JJM and CS contributed to the refinement (review and editing) of the draft. CS supervised all steps of this systematic review. CS obtained the financial support for this systematic review. All the authors reviewed and agreed to the final version submitted.

Funding: This work was in part funded by a mandate of the Swiss Cancer Screening Committee for assessing HPV-based cervical cancer screening (https://cancerscreeningcommittee.ch/en/topics/cervical-cancer-screening/; grant number: ZVK2019102803). The funder had no role in study design and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Arbyn M, Rebolj M, De Kok IMCM, et al. The challenges of organising cervical screening programmes in the 15 old member states of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2671–8. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murphy J, Kennedy EB, Dunn S, et al. HPV testing in primary cervical screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:443–52. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35241-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014;383:524–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crosbie EJ, Einstein MH, Franceschi S, et al. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2013;382:889–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60022-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 1999;189:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australian Government Department of Health . About the national cervical screening program. Available: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/national-cervical-screening-program/about-the-national-cervical-screening-program#the-new-cervical-screening-test-is-more-effective

- 7. Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid . Cervical cancer screening programme. Available: https://www.rivm.nl/en/cervical-cancer-screening-programme

- 8. Government Digital Service (UK) . Cervical screening: programme overview. Available: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/cervical-screening-programme-overview

- 9. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care . Recommendations on screening for cervical cancer. Can Med Assoc J 2013;185:35–45. 10.1503/cmaj.121505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, de Vuyst H, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001351. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. El Sherif R, Pluye P, Gore G, et al. Performance of a mixed filter to identify relevant studies for mixed studies reviews. J Med Libr Assoc 2016;104:47–51. 10.3163/1536-5050.104.1.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. ClinicalTrials.gov . US National Library of Medicine. Available: www.clinicaltrials.gov

- 15. National Library of Medicine . Learning resources database. Available: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/disted/pubmedtutorial/020_190.html

- 16. Veritas Health Innovation Ltd . Covidence. Better systematic review management. Available: https://www.covidence.org/home

- 17. Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:321–46. 10.3322/caac.21628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cancer Council Australia . National Cervical Screening Program - Guidelines for the management of screen-detected abnormalities, screening in specific populations and investigation of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Available: https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cervical-cancer-screening

- 19. Conceição P, Assa J, Calderon C. Human development report 2019, 2019. Available: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2019.pdf

- 20. Sušnik J, van der Zaag P. Correlation and causation between the UN human development index and national and personal wealth and resource exploitation. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 2017;30:1705–23. 10.1080/1331677X.2017.1383175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chorley AJ, Marlow LAV, Forster AS, et al. Experiences of cervical screening and barriers to participation in the context of an organised programme: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Psychooncology 2017;26:161–72. 10.1002/pon.4126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chao YS, Clark M, Carson E. CADTH optimal use reports. in: HPV testing for primary cervical cancer screening: a health technology assessment. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:29–45. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information 2018;34:285–91. 10.3233/EFI-180221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCaffery K, Forrest S, Waller J, et al. Attitudes towards HPV testing: a qualitative study of beliefs among Indian, Pakistani, African-Caribbean and white British women in the UK. Br J Cancer 2003;88:42–6. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCaffery K, Waller J, Nazroo J, et al. Social and psychological impact of HPV testing in cervical screening: a qualitative study. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:169–74. 10.1136/sti.2005.016436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patel H, Moss EL, Sherman SM. HPV primary cervical screening in England: women's awareness and attitudes. Psychooncology 2018;27:1559–64. 10.1002/pon.4694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dodd RH, Mac OA, McCaffery KJ. Women's experiences of the renewed National Cervical Screening Program in Australia 12 months following implementation: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e039041. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagendiram A, Bidgood R, Banks J, et al. Knowledge and perspectives of the new National Cervical Screening Program: a qualitative interview study of North Queensland women-'I could be that one percent'. BMJ Open 2020;10:e034483. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Silver MI, Rositch AF, Burke AE, et al. Patient concerns about human papillomavirus testing and 5-year intervals in routine cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:317–29. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gerend MA, Shepherd MA, Kaltz EA, et al. Understanding women's hesitancy to undergo less frequent cervical cancer screening. Prev Med 2017;95:96–102. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Saraiya M, Kwan A, Cooper CP. Primary HPV testing: U.S. women's awareness and acceptance of an emerging screening modality. Prev Med 2018;108:111–4. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ogilvie GS, Smith LW, van Niekerk DJ, et al. Women's intentions to receive cervical cancer screening with primary human papillomavirus testing. Int J Cancer 2013;133:2934–43. 10.1002/ijc.28324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thompson EL, Galvin AM, Daley EM, et al. Recent changes in cervical cancer screening guidelines: U.S. women's willingness for HPV testing instead of Pap testing. Prev Med 2020;130:105928. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jayasinghe Y, Rangiah C, Gorelik A, et al. Primary HPV DNA based cervical cancer screening at 25 years: views of young Australian women aged 16-28 years. J Clin Virol 2016;76 Suppl 1:S74–80. 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith LW, Racey CS, Gondara L, et al. Women's acceptability of and experience with primary human papillomavirus testing for cervix screening: HPV focal trial cross-sectional online survey results. BMJ Open 2021;11:e052084. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Choi BCK, Pak AWP. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev Chronic Dis 2005;2:A13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer . Cervical carcinoma and sexual behavior: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 15,461 women with cervical carcinoma and 29,164 women without cervical carcinoma from 21 epidemiological studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:1060–9. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Obermair HM, Dodd RH, Bonner C, et al. 'It has saved thousands of lives, so why change it?' Content analysis of objections to cervical screening programme changes in Australia. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019171. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arbyn M, Gultekin M, Morice P, et al. The European response to the WHO call to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem. Int J Cancer 2021;148:277–84. 10.1002/ijc.33189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Evans WD, Lantz PM, Mead K, et al. Adherence to clinical preventive services guidelines: population-based online randomized trial. SSM Popul Health 2015;1:48–55. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saei Ghare Naz M, Kariman N, Ebadi A, et al. Educational interventions for cervical cancer screening behavior of women: a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2018;19:875–84. 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.4.875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chelimo C, Wouldes TA, Cameron LD, et al. Risk factors for and prevention of human papillomaviruses (HPV), genital warts and cervical cancer. J Infect 2013;66:207–17. 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA 2007;297:813–9. 10.1001/jama.297.8.813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses 2017;9:267. 10.3390/v9100267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]