Abstract

Objective

Evaluate the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, an anti-interleukin-12/23 p40 antibody, in a phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled study of patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) despite receiving standard-of-care.

Methods

Active SLE patients (SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) ≥6 during screening and SLEDAI-2K ≥4 for clinical features at week 0) despite receiving oral glucocorticoids, antimalarials, or immunomodulatory drugs were randomised (3:2) to receive ustekinumab (intravenous infusion ~6 mg/kg at week 0, followed by subcutaneous injections of ustekinumab 90 mg at week 8 and every 8 weeks) or placebo through week 48. The primary endpoint was SLE Responder Index (SRI)-4 at week 52, and major secondary endpoints included time to flare through week 52 and SRI-4 at week 24.

Results

At baseline, 516 patients were randomised to placebo (n=208) or ustekinumab (n=308). Following the planned interim analysis, the sponsor discontinued the study due to lack of efficacy but no safety concerns. Efficacy analyses included 289 patients (placebo, n=116; ustekinumab, n=173) who completed or would have had a week 52 visit at study discontinuation. At week 52, 44% of ustekinumab patients and 56% of placebo patients had an SRI-4 response; there were no appreciable differences between the treatment groups in the major secondary endpoints. Through week 52, 28% of ustekinumab patients and 32% of placebo patients had a British Isles Lupus Assessment Group flare, with a mean time to first flare of 204.7 and 200.4 days, respectively. Through week 52, 70% of ustekinumab patients and 74% of placebo patients had ≥1 adverse event.

Conclusions

Ustekinumab did not demonstrate superiority over placebo in this population of adults with active SLE; adverse events were consistent with the known safety profile of ustekinumab.

Trial registration number

Keywords: lupus erythematosus, systemic; biological therapy; autoimmune diseases

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

An unmet need remains for improved treatment options for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), who continue to experience a high disease burden. A phase 2 study of ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibiting the interleukin-12/23 p40 subunit, demonstrated efficacy in patients with active SLE.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In the phase 3 LOTUS study of ustekinumab in patients with active SLE, the primary and major secondary endpoints were not achieved; thus, there was insufficient evidence to support continuation of this study. Safety results were consistent with the known safety profile of ustekinumab.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The LOTUS results add to the body of research in SLE treatments and improve the understanding of the pathogenesis of SLE. Additionally, aspects of the LOTUS study design may be useful in optimising future studies of SLE treatments.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a heterogeneous and biologically complex chronic autoimmune disease that can present with a wide-ranging constellation of symptoms affecting multiple organ systems, with patients commonly experiencing arthralgia/arthritis and skin rashes.1 Conventional therapies include oral glucocorticoids, antimalarial and/or immunosuppressive therapies to control inflammation. Therapies approved more recently are belimumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting B lymphocyte stimulator,2 anifrolumab, a type 1 interferon (IFN) receptor antagonist,3 and voclosporin in lupus nephritis, an immunosuppressant inhibiting calcineurin.4 Advances in general medical care have resulted in improved outcomes in these patients; however, disease burden with SLE remains high with patients often experiencing significant work disability and an increased risk of mortality compared with the general population.5–7

The aetiology of SLE remains unclear, with several molecular pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of this disease. Elevated levels of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 have been found in serum and tissue samples from patients with SLE,8–10 with expression of the shared p40 subunit being upregulated in untreated SLE patients in comparison with treated patients.11 Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibiting the IL-12/23 p40 subunit,12 is approved for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and active psoriatic arthritis and was identified in a previous meta-analysis as being a top candidate for repositioning in SLE.13

The efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active SLE was evaluated in a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled study.14 15 Among patients who entered the optional long-term extension, greater proportions of ustekinumab-treated patients achieved an SLE Responder Index (SRI)-4 composite response at week 24 compared with placebo, and response rates were maintained through 2 years.16 Here, we report the efficacy and safety results of the subsequent phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled study (LOTUS; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03517722) of ustekinumab in patients with active SLE.

Methods

Patients

Eligible patients were aged 16–75 years (inclusive) with a diagnosis of SLE and a documented history of meeting the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for SLE ≥3 months prior to first study agent administration. Patients had active SLE (screening SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) ≥6 and baseline SLEDAI-2K ≥4 for clinical features) despite receiving stable doses of ≥1 of the following: oral glucocorticoids (≤20 mg/day prednisone or equivalent), antimalarials (≤250 mg/day chloroquine, ≤400 mg/day hydroxychloroquine) or immunomodulatory drugs (mycophenolate mofetil ≤2 g/day, mycophenolic acid ≤1.5 g/day, azathioprine/6 mercaptopurine ≤2 mg/kg/day, oral methotrexate (MTX) ≤25 mg/week, or subcutaneous or intramuscular MTX ≤20 mg/week). All patients had to have ≥1 previous well-documented unequivocally positive test for ≥1 of the following: antinuclear, anti-dsDNA, or anti-Smith antibodies as well as ≥1 positive test result during screening. Other inclusion criteria included: ≥1 British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG)17 A and/or ≥2 BILAG B domain scores at screening and Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI)18 activity score ≥4 or≥4 joints with pain and signs of inflammation (active joints) at screening and/or week 0.

Concomitant use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or other analgesics, or select topical medications for cutaneous disease was permitted at stable doses. Patients were excluded if they had any unstable or progressive manifestation of SLE (eg, active class III or IV glomerulonephritis, systemic vasculitis, or active central nervous system involvement) or other inflammatory diseases that might confound efficacy assessments. Patients could not have received previous treatment with systemic immunomodulatory drugs; adrenocorticotropic hormone; oral or intravenous cyclophosphamide or intravenous cyclophosphamide; B-cell targeted therapies or B-cell depleting therapy (or have evidence of continued B-cell depletion following such therapy); immunomodulatory biological therapy within prespecified timeframes prior to screening or study agent administration. All patients were naïve to ustekinumab.

Study design

Patients were randomised (3:2) to ustekinumab (intravenous infusion of ~6 mg/kg at week 0, then subcutaneous injections of ustekinumab 90 mg at week 8 and every 8 weeks thereafter) or placebo (infusion at week 0, then subcutaneous injections at week 8 and every 8 weeks) with crossover to ustekinumab at week 52. The planned study duration included study agent administration through week 160, with safety follow-up through week 176. However, following a prespecified interim efficacy analysis, the study was discontinued early due to lack of efficacy.

Randomisation included the following stratification factors: race (white, black or other), presence of lupus nephritis (ever; yes/no), composite of baseline SLE medications and SLEDAI-2K score (high medications and SLEDAI-2K≥10, high medications and SLEDAI-2K<10, medium medications and SLEDAI-2K≥10, medium medications and SLEDAI-2K<10). High medication use was defined as receiving any of the following: ≥15 mg/week MTX, or ≥1.5 mg/kg/day azathioprine/6 mercaptopurine, or ≥1.5 g/day mycophenolate mofetil/≥1.125 g/day mycophenolic acid, and/or ≥15 mg/day prednisone or equivalent; all other medication use was classified as medium.

Assessments

Global clinical efficacy was assessed using the SRI-4 composite response: ≥4 points reduction in SLEDAI-2K score, no new BILAG A or no more than 1 BILAG B domain score, and no worsening (<10% worsening from baseline) of physician global assessment, without meeting the treatment failure criteria. Other assessments included active joint assessment (tender and swollen joints and signs of inflammation), CLASI activity score for mucocutaneous disease, the Physical and Mental Component Summary scores of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36 PCS/MCS; minimal clinically important difference (MCID): change ≥2.5)19 and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue; MCID: change ≥4) score for fatigue. SLE flares were assessed using the BILAG with a severe flare defined as ≥1 new BILAG A domain score and a moderate flare defined as ≥2 new BILAG B domain scores.

Safety was monitored throughout the study through adverse event (AE) reporting and routine blood chemistry and haematology tests. Blood samples were collected at regular intervals for assessing the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ustekinumab and the presence of antibodies to ustekinumab. Serum levels of pharmacodynamic markers were assessed using the Meso Scale Discovery platform (IFNγ and p40), Quanterix’s single molecule array (Simoa) technology (IFNα), and the high-sensitivity Single Molecule Counting Erenna Immunoassay (IL-17F and IL-22) in a representative biomarker subgroup. Samples from demographically matched healthy subjects (n=30) were procured independently (BioIVT, Westbury, NY) as a control group for biomarker analyses. Antibodies to ustekinumab were assessed using a validated drug-tolerant electrochemiluminescent immunoassay.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients achieving an SRI-4 composite response at week 52. Secondary endpoints were to be tested in a hierarchical manner as follows: time to first flare (≥1 new BILAG A or ≥2 new BILAG B scores) through week 52, proportion of patients with an SRI-4 composite response at week 24, proportion of patients with joint response (≥50% improvement in active joints) at week 52 in patients with ≥4 affected joints at baseline, proportion of patients who achieved a reduction in glucocorticoid dose at week 40 and sustained that reduction through week 52 in patients receiving glucocorticoids at baseline, proportion of patients with CLASI response (≥50% improvement in CLASI activity score) at week 52 in patients with a baseline CLASI ≥4, and proportion of patients who achieved reduction in glucocorticoid dose at week 40 and sustained that reduction through week 52 and achieved SRI-4 composite response at week 52.

For the primary and binary major secondary endpoints, patients with missing data or those meeting ≥1 treatment failure criteria were classified as non-responders. Treatment failure criteria were as follows: increase in baseline dose or initiation of permitted SLE medications between weeks 12 and 52, initiation of a protocol-prohibited medication, or discontinuation of study agent for any reason before week 52. Continuous endpoints were analysed using a mixed model for repeated measures to test differences between treatment groups and adjust for missing data. The models included baseline SLEDAI score as a covariate and treatment, baseline medication use for SLE (high, medium), race, visit, and an interaction of treatment and visit as fixed effects.

The planned sample size of 500 patients (ustekinumab, 300; placebo, 200) would yield ~98% power to detect a significant difference in SRI-4 response rates at week 52 in the two treatment groups assuming response rates of 35% in the placebo group15 20 and 53% in the ustekinumab group. This assumption in response rates would yield an absolute difference of 18% over placebo or an OR of 2.09 with an alpha level of 0.05.

A preplanned interim analysis was performed by an independent data monitoring committee 24 weeks after ~50% of the planned enrollment had been randomised. If the proportion of patients achieving an SRI-4 composite response in the ustekinumab group was ≥2% greater than that in the placebo group, then the study would continue without modification.

The prespecified efficacy analyses were intended to include the full analysis set (FAS; all randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study agent); however, on study discontinuation by the sponsor, efficacy analyses were performed using the modified FAS (mFAS) and included only patients who either completed their week 52 visit or would have had a week 52 visit at the time of study discontinuation by the sponsor. Sensitivity analyses assessed the primary endpoint in subpopulations defined by baseline characteristics: sex, age, weight, body mass index, geographical region, race, ethnicity, SLE medication use, presence of lupus nephritis, SLEDAI-2K score, PGA score, urine protein/creatinine ratio, C3 and C4 levels, and anti-dsDNA status.

Safety analyses included all patients who received ≥1 administration of study agent. The incidence of antibodies to ustekinumab was summarised for all patients who received ustekinumab and had ≥1 available serum sample (post-ustekinumab administration). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses included patients who received ≥1 dose of ustekinumab (partial or complete; IV or SC) and had ≥1 available blood sample (post-ustekinumab administration).

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

LOTUS was conducted at 140 sites in 20 countries. Of 1029 patients screened, 516 were randomised to placebo (n=208) or ustekinumab (n=308) (figure 1). Following the preplanned interim analysis, the futility criteria were met, and the sponsor discontinued the study on 26 June 2020. Data for this report were collected from 3 May 2018 to 5 November 2020.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition of LOTUS participants. mFAS, (including patients who either completed their week 52 visit or would have had a week 52 visit at the time of study discontinuation by the sponsor). mFAS, modified full analysis set.

At the time of study discontinuation, 104 patients in the placebo group and 153 in the ustekinumab group had completed study participation through week 52 (figure 1). The mFAS comprised 116 placebo patients and 173 ustekinumab patients who had completed their week 52 visit or would have had a week 52 visit (based on their last scheduled visit) at the time the study was discontinued.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics are shown in table 1. Among all randomised patients, the placebo group had a lower proportion of female patients and the mean age was higher when compared with the ustekinumab group. Patients in the placebo group had, on average, fewer active joints as well as greater proportions of patients with ≥2 BILAG B domain scores and lupus nephritis. In addition, the proportion of patients with ≥1 BILAG A domain score was higher in the ustekinumab group. Overall, the baseline demographic and disease characteristics of patients included in the mFAS were similar to those for the total study population (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and disease characteristics

| All randomised patients | mFAS* | |||

| Ustekinumab | Placebo | Ustekinumab | Placebo | |

| Patients, n† | 308 | 208 | 173 | 116 |

| Female | 291 (94.5) | 191 (91.8) | 165 (95.4) | 108 (93.1) |

| Age | 42.9±11.4 | 44.5±12.3 | 43.4±11.4 | 45.8±11.3 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 208 (67.5) | 136 (65.4) | 130 (75.1) | 86 (74.1) |

| Black | 24 (7.8) | 18 (8.7) | 14 (8.1) | 10 (8.6) |

| Asian | 57 (18.5) | 46 (22.1) | 22 (12.7) | 20 (17.2) |

| Disease duration (years) | 8.8±8.0 | 9.1±7.6 | 8.8±8.6 | 9.4±7.7 |

| SLEDAI-2K (0–105) | 10.4±3.4 | 10.5±3.7 | 10.5±3.8 | 10.5±3.7 |

| Physician’s global assessment (VAS, 0–3) | 1.8±0.4 | 1.8±0.4 | 1.8±0.5 | 1.8±0.4 |

| BILAG | ||||

| ≥1 BILAG A | 144 (46.8) | 79 (38.0) | 71 (41.0) | 43 (37.1) |

| ≥2 BILAG B | 170 (55.2) | 124 (59.6) | 103 (59.5) | 69 (59.5) |

| Tender joint count | 15.0±11.4 | 13.9±10.4 | 16.6±12.1 | 14.8±11.0 |

| Swollen joint count | 9.1±6.8 | 8.4±6.4 | 9.8±6.9 | 8.7±6.3 |

| Joints with both tenderness and inflammation | 8.7±6.5 | 7.8±6.0 | 9.5±6.8 | 8.2±6.0 |

| CLASI activity score (0–70) | ||||

| Patients, n | 307 | 208 | 172 | 116 |

| Mean±SD | 8.4±6.8 | 7.9±6.4 | 7.6±6.0 | 8.0±5.4 |

| ANA‡ | 282/302 (93.4) | 189/204 (92.6) | 155/167 (92.8) | 105/113 (92.9) |

| Anti-dsDNA (>75 kIU/L)‡ | 113 (36.7) | 77 (37.0) | 59 (34.1) | 36 (31.0) |

| Low complement‡ | ||||

| C3 | 129 (41.9) | 90 (43.3) | 66 (38.2) | 49 (42.2) |

| C4 | 79 (25.6) | 57 (27.4) | 35 (20.2) | 26 (22.4) |

| Patients with lupus nephritis | 52 (16.9) | 48 (23.1) | 31 (17.9) | 23 (19.8) |

| Concomitant medications | ||||

| Oral glucocorticoids | 249 (80.8) | 163 (78.4) | 140 (80.9) | 92 (79.3) |

| Dose (mg/day) | 9.7±4.8 | 9.6±5.5 | 9.3±4.5 | 8.8±4.6 |

| Antimalarials | 223 (72.4) | 155 (74.5) | 122 (70.5) | 86 (74.1) |

Data reported as n (%), n/N (%), or mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted.

*The mFAS included patients who either completed their week 52 visit or would have had a week 52 visit at the time of study discontinuation by the sponsor.

†Patients were enrolled at sites located in Argentina (7 sites), Bulgaria (3 sites), Canada (1 site), China (3 sites), Colombia (6 sites), Germany (4 sites), Hungary (3 sites), Japan (18 sites), Lithuania (4 sites), Poland (8 sites), Portugal (1 site), Republic of Korea (3 sites), Russian Federation (7 sites), Serbia (7 sites), Spain (5 sites), South Africa (4 sites), Taiwan (5 sites), Thailand (5 sites), Ukraine (6 sites), USA (40 sites).

‡Analyses of ANA, anti-ds-DNA, C3, and C4 were performed by a central laboratory. The presence of ANA (determined as either positive or negative) was assessed using the Kallestad HEp-2 indirect fluorescent antibody method (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Anti-dsDNA was measured using the QUANTA Lite dsDNA SC ELISA (INOVA diagnostics) with the following reference values: negative defined as <30 IU/mL, borderline defined as 30–75 IU/mL, positive defined as >75 IU/mL. C3 levels were measured using Tina-quant complement C3c V.2 kit (Roche Diagnostics) with a reference range of 0.90–1.80 g/L. C4 levels were measured using the Tina-quant complement C4 V.2 kit (Roche Diagnostic) with a reference range of 0.1–0.4 g/L.

ANA, anti-nuclear antibodies; BILAG, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group; CLASI, Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index; dsDNA, double-strand DNA; mFAS, modified full analysis set; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Efficacy

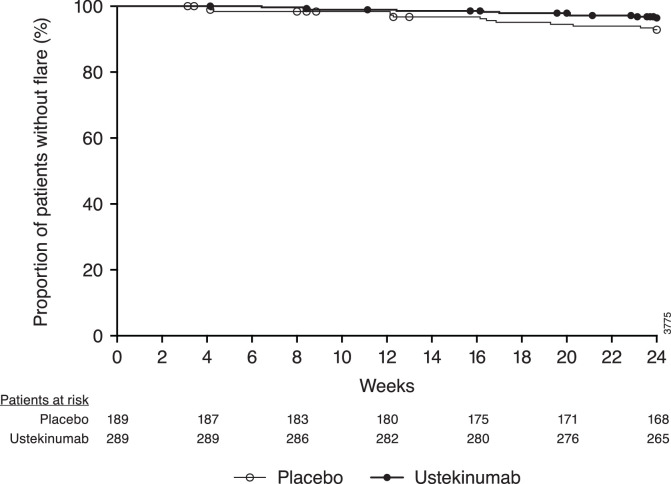

The primary and major secondary endpoints were not achieved (figure 2). In the mFAS population, 44% of ustekinumab patients and 56% of placebo patients had an SRI-4 composite response at week 52 (figure 2). Sensitivity analyses of the primary endpoint in subpopulations defined by various demographic and disease characteristics were consistent with the mFAS (data not shown). Through week 52, 28% of patients in the ustekinumab group and 32% of patients in the placebo group had a BILAG flare, with a mean time to first flare of 204.7 and 200.4 days, respectively (figure 3). There were no appreciable differences between treatment groups in the response rates for SRI-4 at week 24 or joint or CLASI activity improvement at week 52 (figure 2). In a post hoc analysis of the 197 patients who were not included in the mFAS population, 46% (55/120) of patients in the ustekinumab group and 34% (26/77) in the placebo group had an SRI-4 composite response at week 24 (nominal p=0.125).

Figure 2.

The proportion of patients achieving an SRI-4 composite response at week 52 (A) and week 24 (B), a reduction in glucocorticoid dose at week 40 that was sustained through week 52 (C), joint response at week 52 (D), CLASI response at week 52 (E), and a reduction in glucocorticoid dose at week 40 that was sustained through week 52 together with an SRI-4 composite response at week 52 (F). Analyses were performed using the modified Full Analysis Set population, excluding patients whose week 52 visit was projected to occur after the early study discontinuation by the sponsor. CLASI, Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index; SRI-4, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder Index-4.

Figure 3.

Time to first BILAG flare. BILAG, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group

Among patients receiving concomitant glucocorticoids at baseline, 44% of those in the ustekinumab group had a reduction in glucocorticoid dose at week 40 that was sustained through week 52 vs 29% of placebo patients (nominal p=0.040). There was a trend favouring ustekinumab in the proportion of patients with both a reduction in glucocorticoid dose at week 40 that was sustained through week 52 and an SRI-4 composite response at week 52 (30% vs 24%, nominal p=0.380). No treatment effect with ustekinumab was observed in an exploratory analysis of SRI-4 response rates at week 52 with patients stratified by week 40 glucocorticoid dose (≥7.5 mg or <7.5 mg) (data not shown).

Among patients in the mFAS, 11% in the placebo group and 9% in the ustekinumab group had a clinically meaningful improvement in FACIT-Fatigue score at week 52; 58% and 48%, respectively, had an improvement ≥MCID in SF-36 PCS score, and 43% and 38%, respectively, had an improvement ≥MCID in SF-36 MCS score.

Safety

Through week 52, 74% of placebo patients and 70% of ustekinumab patients reported ≥1 AE (table 2), with infections being the most common type (44% and 43%, respectively). Serious AEs occurred in 28 (13%) patients in the placebo group and 37 (12%) in the ustekinumab group; serious infections occurred in 8 (4%) and 15 (5%) patients, respectively (table 2). Serious infections reported in both treatment groups through week 52 were pneumonia (placebo, n=1; ustekinumab, n=4) and urinary tract infection (placebo, n=2; ustekinumab, n=1). Other serious infections in the placebo group were herpes zoster, sepsis, urosepsis, bronchitis, and diverticulitis (all singular events). In the ustekinumab group, serious infections through week 52 included gastroenteritis, staphylococcal endocarditis, tonsillitis and vulval cellulitis. During the extension, four patients (ustekinumab group) reported a serious infection: COVID-19 (n=2), gastritis (n=1) and pulmonary tuberculosis (n=1; negative chest radiograph and Quantiferon TB gold test at screening). No opportunistic infections occurred. AEs reported during the extension were similar in type and frequency to those reported through week 52 (table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse events through end of study in LOTUS

| Placebo (weeks 0–52) |

Ustekinumab (weeks 0–52) |

Placebo→ ustekinumab (weeks 52–176) | Ustekinumab (weeks 52–176) |

All ustekinumab* | |

| Patients, n | 208 | 307 | 88 | 134 | 395 |

| Mean duration of follow-up (weeks) | 50.4 | 50.1 | 29.7 | 29.7 | 55.6 |

| Patients with ≥1 AE | 155 (74.5) | 214 (69.7) | 26 (29.5) | 37 (27.6) | 246 (62.3) |

| Patients with ≥1 SAE | 28 (13.5) | 37 (12.1) | 5 (5.7) | 7 (5.2) | 49 (12.4) |

| Patients with ≥1 infection | 92 (44.2) | 132 (43.0) | 9 (10.2) | 23 (17.2) | 149 (37.7) |

| Patients with ≥1 serious infection | 8 (3.8) | 15 (4.9) | 0 | 4 (3.0) | 19 (4.8) |

| COVID-19-related AEs | 0 | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 4 (3.0) | 6 (1.5) |

| COVID-19-related SAEs | 0 | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 4 (1.0) |

| Patients with ≥1 infusion reaction | 0 | 5 (1.6) | -- | -- | -- |

| Patients with ≥1 injection-site reaction | 0 | 5 (1.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 6 (1.5) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 9 (4.3) | 11 (3.6) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 12 (3.0) |

| Deaths† | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 5 (1.3) |

*All patients who received ≥1 dose of ustekinumab, including patients who crossed over from placebo.

†One death occurred in the placebo group (splenic rupture). In the ustekinumab group, 4 deaths occurred prior to week 52 (hypovolaemic shock, cardiac failure due to systemic lupus erythematosus myocarditis (patient was discharged against medical advice), haemorrhagic stroke (patient had a history of arterial hypertension) and staphylococcal endocarditis), and one death (COVID-19; history of asthma) occurred after week 52.

AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event.

Five patients reported a major adverse cardiovascular event: acute myocardial infarction in the placebo group (n=2), cerebral infarction (n=1) and embolic stroke (n=1) in the ustekinumab group and acute myocardial infarction in a placebo→ustekinumab patient. Two malignancies occurred: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (placebo, n=1) and gastric cancer (ustekinumab, n=1) through week 52; both patients discontinued study agent. No additional malignancies occurred through week 176.

One death was reported in the placebo group (splenic rupture). Five deaths occurred in the ustekinumab group: hypovolaemic shock, cardiac failure due to lupus myocarditis, haemorrhagic stroke (history of arterial hypertension), staphylococcal endocarditis, and COVID-19 (history of asthma).

Five patients, all in the ustekinumab group, had an infusion reaction; of these, two discontinued as a result. Injection-site reactions occurred in five ustekinumab patients and no placebo patient through week 52. After week 52, one patient (placebo→ustekinumab group) had an injection-site reaction. All injection-site reactions were considered mild.

Immunogenicity

Through week 48, 300 patients received ≥1 partial or complete dose of ustekinumab and had ≥1 post-administration serum sample. Of these patients, 24 (8%) tested positive for antibodies to ustekinumab, with 16 testing positive for neutralising antibodies. Through week 52, 1/24 (4%) patient who was positive for antibodies to ustekinumab and 4/276 (1%) patients who were negative for antibodies to ustekinumab experienced an injection-site reaction.

Pharmacokinetics

Among patients randomised to ustekinumab, 303 were included in the pharmacokinetic analyses. Median trough serum ustekinumab concentrations reached steady state by week 24 (2.31 µg/mL) and were maintained through week 80 (2.09 µg/mL). Median serum ustekinumab concentrations at week 24 were similar for patients with and without renal disease (2.15 and 2.31 µg/mL, respectively); however, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of patients with lupus nephritis (n=51 with available data, mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR): 0.93 mL/s/m2; other patients, n=252, mean GFR: 0.98 mL/s/m2).

Pharmacodynamics

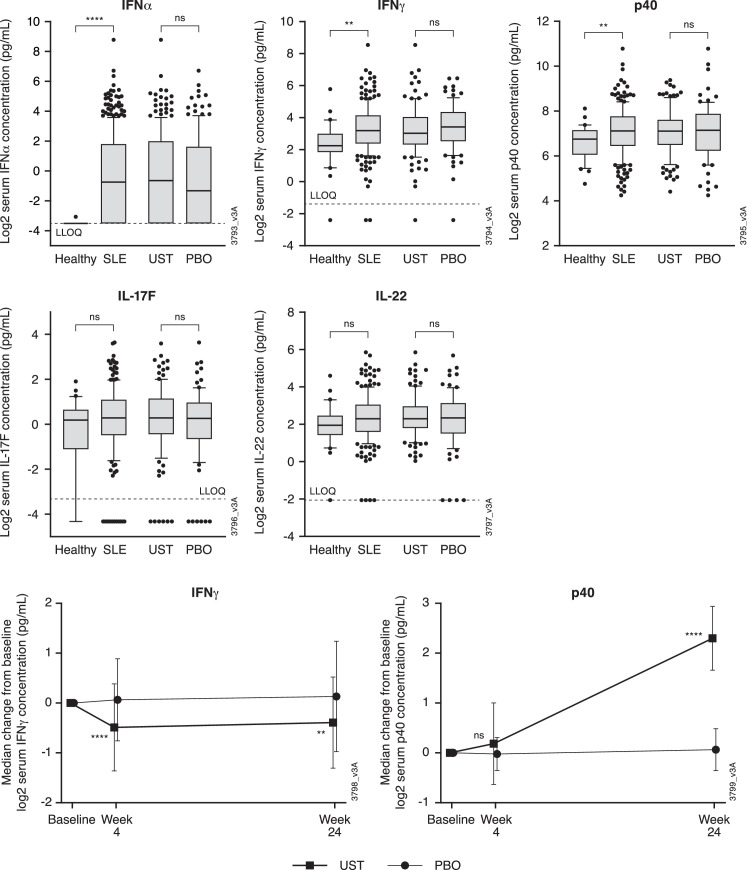

Serum samples from 201 patients (ustekinumab, n=115; placebo, n=86) were used for pharmacodynamic analyses. Baseline characteristics for this population were similar to those of the FAS (online supplemental table 1). Baseline serum concentrations of IFNα, IFNγ and p40 in LOTUS patients were higher than those from healthy controls; serum levels of IL-17F and IL-22 were similar in LOTUS patients and healthy controls. There were no apparent differences in baseline levels of any of the assessed biomarkers between the treatment groups (figure 4). At week 24, serum p40 levels were increased and IFNγ levels were decreased in the ustekinumab group compared with baseline, with no apparent changes in the placebo group (figure 4). No treatment effect was seen in serum concentrations of IFNα, IL-17F and IL-22 (data not shown). Among the biomarkers analysed, changes in serum levels did not appear to be associated with SRI-4 response at week 24 (online supplemental figure 1).

Figure 4.

Baseline serum concentrations of IFNα, IFNγ, p40, IL-17F and IL-22 in LOTUS patients and healthy controls and median change from baseline in serum concentrations of IFNγ and p40 through week 24. Each box represents the 25th to 75th percentiles. Lines inside the boxes represent the median. The upper line extends to the largest value ≤1.5 × IQR; the lower line extends to the smallest value ≤1.5 × IQR. Data beyond the end of the lines represents outlier points. **P<0.01, ****p<0.0001. IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification; PBO, placebo; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; UST, ustekinumab.

ard-2022-222858supp001.pdf (94.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

In the earlier phase 2 study of ustekinumab in patients with SLE, a significantly greater proportion of ustekinumab-treated patients achieved an SRI-4 composite response at week 24 compared with placebo (primary endpoint).15 However, these results were not confirmed in the larger phase 3 LOTUS study. The high response rate seen in the placebo/standard-of-care (SOC) group in LOTUS, with nearly 60% of these patients achieving an SRI-4 response at week 52, may have blunted the ability to assess the efficacy of ustekinumab. In recent trials of other compounds in patients with SLE, response rates in placebo/SOC groups were lower than that observed in LOTUS (week 24 SRI-4 response rates: placebo/SOC group, 48% vs baricitinib, 64%21 and week 52 SRI-4 response rates: placebo/SOC group, 48% vs belimumab, 61%).22 The week 52 SRI-4 response rate of 56% in the LOTUS placebo/SOC group limits the ability to see a signal for ustekinumab.

Race and ethnicity have been shown to influence both organ damage accrual and response to treatment in SLE patients.23 24 The majority of patients in both the phase 2 and LOTUS studies were white, which may have biased the populations towards having less severe disease. However, sensitivity analyses by demographic and disease characteristics were similar to results in the overall mFAS. There were important differences between these studies that should be noted. The phase 2 study was smaller (102 patients), and placebo patients crossed over to ustekinumab at week 24 (the time point for primary endpoint analysis). Patients in ustekinumab and placebo groups, respectively, in the phase 2 study had slightly higher mean baseline SLEDAI-2K scores of 10.6 and 11.4 compared with LOTUS patients (All patients: 10.4 and 10.5; mFAS: 10.5 and 10.5). However, on average, patients in the phase 2 study15 had a lower prevalence of lupus nephritis, fewer swollen, tender and active joints, and less severe skin disease at baseline than did LOTUS patients. Additionally, in the phase 2 study, BILAG A domain manifestations were more common in the placebo group (52%) vs ustekinumab (45%), while in the LOTUS population, BILAG A domain manifestations were more common in the ustekinumab group (All patients: 47% vs 38%; mFAS: 41% vs 37%).

Concomitant use of glucocorticoids was permitted in the phase 2 study at stable doses through week 28 with limited exemptions for dose adjustment, thus tapering was not generally permitted in the phase 2 study. In contrast, glucocorticoid tapering was strongly encouraged when clinically appropriate between weeks 24 and 40 in LOTUS, but a mandatory tapering regimen was not included in the study design. In addition, no dose adjustment was permitted between weeks 40 and 52, during which the primary endpoint was assessed. Because steroid tapering was not mandatory in LOTUS, investigators could discontinue tapering if disease activity increased without meeting the treatment failure criteria, thus favouring the placebo group in achieving the primary endpoint at week 52. Including such a directive regimen may provide more information on the glucocorticoid-sparing properties of a medication, but can result in a lower response to a study medication as measured by standard outcomes such as the SRI-4.

In both the phase 2 and LOTUS studies, a modified version of the SLEDAI-2K was used. All descriptors had to be present at the time of the screening visit, excluding seizure, fever, pericarditis/pleuritis, mucosal ulcers, diffuse alopecia and lupus headache. However, during postbaseline efficacy assessment visits, the presence of some variables was assessed based on the preceding 30 days while the presence of other variables (including visual disturbance, cranial nerve disorder (motor power and sensory deficit), cerebrovascular accident (motor and sensory deficit), vasculitis, arthritis, myositis (motor power), rash and alopecia (patchy)) was only assessed on the day of the study visit. Post hoc sensitivity analyses completed in both studies using the BILAG to reconstruct the SLEDAI-2K taking into consideration the preceding 30 days for all variables resulted in inconsistencies in response rates in both the phase 2 and LOTUS studies. One can speculate that this was due to activities that occurred during the preceding 30 days not being included in the SLEDAI score.

No new safety signals were identified in the LOTUS study, and the overall safety results were consistent with the known safety profile of ustekinumab. Infections were the most commonly reported type of AE.

The pharmacodynamic effects observed following ustekinumab treatment in LOTUS were generally consistent with those observed in the phase 2 study.25 In both studies, comparable post-treatment increases in p40 levels and decreases in IFNγ levels were observed. Changes in p40 levels were not associated with an SRI-4 response in either study; however, while SRI-4 responders in the phase 2 study had greater decreases in IFNγ than did non-responders, no association was observed between decreases in IFNγ levels and SRI-4 response in the LOTUS patient population. Treatment with ustekinumab did not result in reductions in IL-17F or IL-22 in either study. In contrast, decreases in serum levels of IL-17F and/or IL-22 have been consistently observed following ustekinumab treatment in patients with psoriasis26 and psoriatic arthritis,27 in which ustekinumab has demonstrated significant clinical efficacy. Thus, taken together with the clinical efficacy assessments, these results suggest that although IL-23 may be involved in the pathogenesis of SLE, it is not an overarching target for these patients.

In summary, although the phase 2 results appeared robust, the phase 3 LOTUS study met futility criteria and was discontinued early. The primary and key secondary endpoints were not achieved in the overall study population or in the subpopulations evaluated in these analyses; despite a numerical trend suggesting that steroid tapering was possible to a greater extent in the ustekinumab group compared with the placebo group, there was insufficient evidence to support continuation of development of ustekinumab in patients with SLE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katie Abouzahr, MD, and Marc Chevrier, MD, PhD, of Janssen Research & Development, and Yun Irene Gregan, MD, MS, Shawn Rose, MD, PhD, and Zhenling Yao, PhD, formerly of Janssen Research & Development, for their contributions to study design, data collection and/or data analysis. Medical writing support was provided by Rebecca Clemente, PhD, of Janssen Scientific Affairs under the direction of the authors in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461-4).

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Contributors: Substantial intellectual contribution to conception and design: RFvV, KCK, TD, BHH, YT, RMG, KF, LS, KHL, PB, QCZ. Acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data: RFvV, KCK, TD, BHH, YT, RMG, CS, KF, SG, LS, PG, KHL, PB, QCZ. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: RFvV, KCK, TD, BHH, YT, RMG, CS, KF, SG, LS, PG, KHL, PB, QCZ. Final approval of the version to be published: RFvV, KCK, TD, BHH, YT, RMG, CS, KF, SG, LS, PG, KHL, PB, QCZ. RFvV is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by Janssen Research and Development.

Competing interests: RFvV has received grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB; consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biogen, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen, Miltenyi, Pfizer, UCB; honoraria/speaking fees from AbbVie, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, R-Pharma, and UCB. KCK has received grants from Acceleron, Alexion, Alpine, Horizon, Idorsia, Kirin, the National Institutes of Health, Provention Bio, Sanford Consortium, and UCB; consulting fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Aurinia, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EquilliumBio, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Kang Pu, KezarBio, Merck, and Novartis. TD has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from AbbVie, Celgene/Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Genentech/Roche, and UCB and support for conducting clinical studies (paid to the university) from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis, Roche and UCB. BHH has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Aurinia, GlaxoSmithKline and UCB. YT has received speaking fees and/or honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, and Pfizer; and received research grants from AbbVie, Asahi-Kasei, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chugai, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, and Takeda. RMG, CS, KF, SG, LS, PG, KHL and QCZ are employees of Janssen Research & Development and own stock in Johnson & Johnson, of which Janssen Research & Development, is a wholly owned subsidiary. PB is an employee of Immunology Strategic Market Access, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by In the US, the protocol was approved by Central IRB/IEC - Chesapeake IRB, 6940 Columbia Gateway Drive, Suite 110, Columbia, MD, 21046. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Fava A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and clinical management. J Autoimmun 2019;96:1–13. 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benlysta: Package insert. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline, 2021.

- 3. Saphnelo: Package insert. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, 2021.

- 4. Lupkynis: Package insert. Victoria, BC: Aurinia Pharmaceuticals Inc., 2021.

- 5. Lopez R, Davidson JE, Beeby MD, et al. Lupus disease activity and the risk of subsequent organ damage and mortality in a large lupus cohort. Rheumatology 2012;51:491–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peschken CA, Wang Y, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Persistent disease activity remains a burden for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2019;46:166–75. 10.3899/jrheum.171454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Utset TO, Baskaran A, Segal BM, et al. Work disability, lost productivity and associated risk factors in patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med 2015;2:e000058. 10.1136/lupus-2014-000058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dai H, He F, Tsokos GC, et al. Il-23 limits the production of IL-2 and promotes autoimmunity in lupus. J Immunol 2017;199:903–10. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Qiu F, Song L, Yang N, et al. Glucocorticoid downregulates expression of IL-12 family cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus 2013;22:1011–6. 10.1177/0961203313498799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong CK, Lit LCW, Tam LS, et al. Hyperproduction of IL-23 and IL-17 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: implications for TH17-mediated inflammation in auto-immunity. Clin Immunol 2008;127:385–93. 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang X, Hua J, Shen N, et al. Dysregulated expression of interleukin-23 and interleukin-12 subunits in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Mod Rheumatol 2007;17:220–3. 10.3109/s10165-007-0568-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stelara: Package insert. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc., 2020.

- 13. Grammer AC, Ryals MM, Heuer SE, et al. Drug repositioning in SLE: crowd-sourcing, literature-mining and big data analysis. Lupus 2016;25:1150–70. 10.1177/0961203316657437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Vollenhoven RF, Hahn BH, Tsokos GC, et al. Maintenance of efficacy and safety of ustekinumab through one year in a phase II multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:761–8. 10.1002/art.41179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Vollenhoven RF, Hahn BH, Tsokos GC, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, an IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitor, in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a multicentre, double-blind, phase 2, randomised, controlled study. Lancet 2018;392:1330–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32167-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Vollenhoven RF, Hahn BH, Tsokos GC, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a phase II open-label extension study. J Rheumatol 2022;49:380–7. 10.3899/jrheum.210805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Allen E, et al. BILAG 2004. Development and initial validation of an updated version of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group's disease activity index for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2005;44:902–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin JA, et al. The CLASI (Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol 2005;125:889–94. 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23889.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strand V, Crawford B. Improvement in health-related quality of life in patients with SLE following sustained reductions in anti-dsDNA antibodies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2005;5:317–26. 10.1586/14737167.5.3.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Vollenhoven RF, Petri MA, Cervera R, et al. Belimumab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: high disease activity predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1343–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wallace DJ, Furie RA, Tanaka Y, et al. Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;392:222–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31363-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stohl W, Schwarting A, Okada M, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus: a fifty-two-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1016–27. 10.1002/art.40049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bruce IN, O'Keeffe AG, Farewell V, et al. Factors associated with damage accrual in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the systemic lupus international collaborating clinics (SLICC) inception cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1706–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Litwic AE, Sriranganathan MK, Edwards CJ. Race and the response to therapies for lupus: how strong is the evidence? Int J Clin Rheumtol 2013;8:471–81. 10.2217/ijr.13.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cesaroni M, Seridi L, Loza MJ, et al. Suppression of serum interferon-γ levels as a potential measure of response to ustekinumab treatment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:472–7. 10.1002/art.41547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Campbell K, Branigan P, Yang F. Selective IL-23 blockade with guselkumab (GUS) neutralizes Th17- and psoriasis-associated serum, cellular, and transcriptomic measures more potently than dual IL-12/23 blockade with ustekinumab (UST). Abstracts Exp Dermatol 2018;27:3–58. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Siebert S, Loza MJ, Song Q. Ustekinumab and guselkumab treatment results in differences in serum IL17A, IL17F and CRP levels in psoriatic arthritis patients: a comparison from ustekinumab PH3 and guselkumab PH2 programs. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:A293. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ard-2022-222858supp001.pdf (94.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.