Abstract

Objective

This systematic review evaluates vestibular and balance dysfunction in children with congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV), makes recommendations for clinical practice and informs future research priorities.

Design

MEDLINE, Embase, EMCARE, BMJ Best Practice, Cochrane Library, DynaMed Plus and UpToDate were searched from inception to 20 March 2021 and graded according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) criteria.

Patients

Children with cCMV diagnosed within 3 weeks of life from either blood, saliva and/or urine (using either PCR or culture).

Intervention

Studies of vestibular function and/or balance assessments.

Main outcome measures

Vestibular function and balance.

Results

1371 studies were identified, and subsequently 16 observational studies were eligible for analysis, leading to an overall cohort of 600 children with cCMV. All studies were of low/moderate quality. In 12/16 studies, vestibular function tests were performed. 10/12 reported vestibular dysfunction in ≥40% of children with cCMV. Three studies compared outcomes for children with symptomatic or asymptomatic cCMV at birth; vestibular dysfunction was more frequently reported in children with symptomatic (22%–60%), than asymptomatic cCMV (0%–12.5%). Two studies found that vestibular function deteriorated over time: one in children (mean age 7.2 months) over 10 months and the other (mean age 34.7 months) over 26 months.

Conclusions

Vestibular dysfunction is found in children with symptomatic and asymptomatic cCMV and in those with and without hearing loss. Audiovestibular assessments should be performed as part of neurodevelopmental follow-up in children with cCMV. Case–controlled longitudinal studies are required to more precisely characterise vestibular dysfunction and help determine the efficacy of early supportive interventions.

PROSPERO registration

CRD42019131656.

Keywords: Child Health, Deafness, Epidemiology, Virology, Neonatology

This systematic literature review found congenital infection with cytomegalovirus (cCMV) to be associated with vestibular dysfunction in both symptomatic and asymptomatic children, with and without hearing loss. This highlights the importance of audiovestibular assessments when following-up children with cCMV.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is a leading cause of sensorineural hearing loss and developmental delay worldwide.

The majority of babies with cCMV are asymptomatic at birth.

Vestibular dysfunction is common in children with cCMV-related sensorineural hearing loss and may adversely affect balance and quality of life.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Vestibular dysfunction can occur in children with asymptomatic cCMV and in children with normal hearing.

Vestibular dysfunction can be progressive.

It is important to follow-up infants with cCMV iduring early childhood, assess for hypotonia, head lag, gross motor delay and imbalance.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE AND/OR POLICY

Clinicians should have a low threshold for referral to a paediatric audiovestibular clinic and to paediatric vestibular physiotherapy if there are signs/symptoms of vestibular dysfunction.

Consider testing for cCMV (via stored dried blood spot) in children who present with vestibular dysfunction, balance problems and/or gross developmental delay.

Vestibular function and balance assessments should be considered when investigating the benefits of universal neonatal screening and antiviral treatment.

Introduction

Congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) is the most common non-genetic cause of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) worldwide and affects 0.3%–0.7% of live-born neonates, with higher rates seen in low-income and middle-income countries.1–3 Clinical signs include microcephaly, being small for gestational age, widespread petechiae, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly and chorioretinitis.4 Infants with signs of cCMV at birth are termed ‘symptomatic’; however, up to 90% of infected neonates have no signs of cCMV and are termed ‘asymptomatic’ at birth. The most common sequela of cCMV is SNHL, which may be present at birth or occur later in childhood. SNHL is found in 40%–58% of symptomatic and 12% of asymptomatic infants.2

Vestibular dysfunction can coexist with SNHL, depending on the cause, and is associated with delayed gross motor development, hypotonia, poor balance and impaired spatial awareness. Normal balance is maintained using inputs from the inner ears (vestibular organs), eyes (vision), and muscles and joints (proprioception). Balance disorders due to vestibular impairment can be difficult to diagnose, as causes may be multifactorial, and the brain can compensate for vestibular deficits. Young children may not be able to describe symptoms such as vertigo or unsteadiness.5

Vestibular function can be assessed via a variety of quantitative tests including cervical vestibular myogenic evoked potentials (cVEMPS), the caloric test and video head impulse testing (vHIT). A glossary of assessments is detailed in online supplemental appendix A. Each test measures slightly different elements, so a battery of tests is required to comprehensively assess the vestibular system. The peripheral vestibular system is delineated in online supplemental appendix B. Some tests can be used in infancy (cVEMPs), whereas others require cooperation (vHIT) or may be poorly tolerated (caloric testing).6 Abnormal vestibular function has been described through interchangeable terms such as hypofunction, impairment and dysfunction. In this review, abnormal vestibular function is referred to as dysfunction. Vestibular dysfunction can be reported per affected patient or per affected ear of each patient. Balance function tests include Movement Assessment Battery for Children (online supplemental appendix A).

fetalneonatal-2021-323380supp001.pdf (81.9KB, pdf)

fetalneonatal-2021-323380supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Pathophysiology studies have shown cells with cytomegalic inclusion bodies indicative of infection with CMV in the inner ear of infected infants, including the vestibular system.7–9 Two studies have reported that vestibular dysfunction is more common than SNHL in children with cCMV. Zagólski found that in the ears of 26 infants with cCMV, 15.4% had SNHL and 30.8% had vestibular dysfunction. Pinninti found that in 40 children with asymptomatic cCMV, 17.5% had SNHL but 44.75% had vestibular dysfunction.10 11 However, routine vestibular assessment is currently not part of the recommended follow-up of infants with cCMV in the UK. A recent survey of paediatricians and audiovestibular physicians identified several barriers around vestibular assessment of children with cCMV in the UK, such as lack of time in clinic and insufficient training.12 Vestibular dysfunction is therefore likely to be underdiagnosed in this population, even though vestibular physiotherapy exercises may improve motor outcomes for affected children.13

The objective of this systematic review was to collate evidence, characterise the nature of vestibular dysfunction and balance disorders in cCMV and inform clinical management and future research priorities.

Methods

Search strategy

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (checklist in appendix D).14 We searched MEDLINE, Embase, EMCARE, BMJ Best Practice, Cochrane Library, DynaMed Plus and UpToDate from database creation to 20 March 2021. Search terms described the population (infant/child/adolescent), disease (congenital CMV/cytomegalovirus) and outcome (audiovestibular/vestibular/balance). Synonyms for hearing loss (deafness/hearing impairment/sensorineural/cochlear) were included to identify studies that focused on SNHL but also described vestibular outcomes. Dizziness, vertigo and spatial awareness were synonyms used for vestibular. Only articles in English were included.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible if they included humans with cCMV and investigated vestibular function or balance. Diagnosis of cCMV was by urine or saliva culture and/or urine, saliva or blood (including umbilical cord blood) PCR test, within 3 weeks of life. Interventional and observational studies including case series with n>3 were included.

Data extraction

Titles and abstracts were screened by two authors (AS and HM). Cohen’s kappa value for interobserver agreement was 0.688 (substantial). Data were extracted independently and on study population, design, intervention (vestibular function or balance test) and outcome (evidence of vestibular/balance dysfunction) (AS, HM and GY). All studies were assessed for quality using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist by two authors (AS and GY).

Results

Literature search

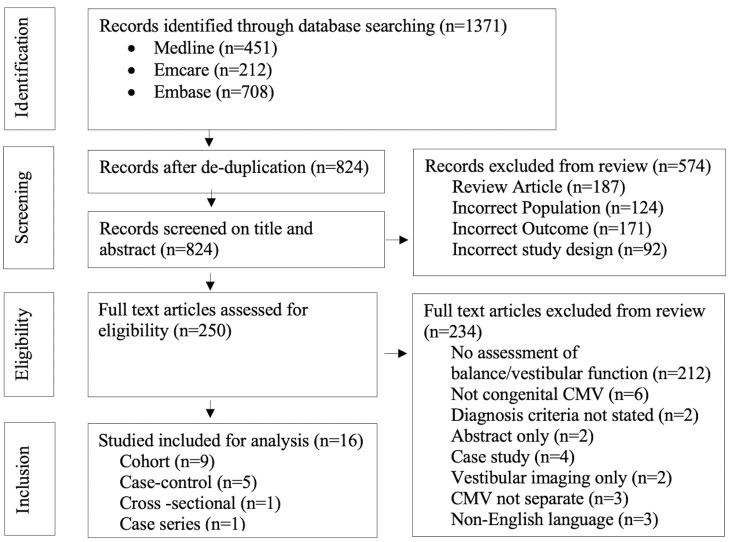

The literature search identified 1371 papers in total. After removing 547 duplicates, 824 articles were reviewed by title and abstract. Two-hundred and fifty met criteria for full-text assessment, and of those, 16 met criteria for inclusion (figure 1). No interventional trials were identified. Of the included studies, 12 reported data on vestibular function through vestibular-specific investigations (table 1) and four studies reported data on balance through non-vestibular specific assessments (table 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics and findings of the eligible studies that performed vestibular-specific assessments

| First author, year, country | Study design | N | N with hearing loss (HL)* | Age (mean)† | Mode of vestibular assessment | STROBE quality | Vision assessment |

Findings |

| Bernard, 2015, France20 |

R Cohort | 22 ScCMV 30 AcCMV |

48 (18 ears with MI/MO HL; 68 ears with SE/PR) CI use not reported |

34.7 months | Caloric EVAR HIT OVAR CVEMP |

Low | Not assessed |

|

| Dhondt, 2019, Belgium23 | Case Series | 4 ScCMV 1 AcCMV |

5 SE/PR (3 using CI) | 2–7.3 years | vHIT Rotatory test Caloric CVEMP OVEMP |

Low | Not assessed |

|

| Dhondt, 2021, Belgium19 | P Cohort | 41 ScCMV 52 AcCMV |

3 AcCMV (1 MO, 2 SE/PR) 14 ScCMV (1 MO, 13 SE/PR) ≥3 using CI |

7.2 months | vHIT Rotatory Test cVEMP |

Moderate-low | Funduscopy |

|

| Inoue, 2013, Japan17 | P Cohort | 8 cCMV | 8 PR (pre-CI) | 38 months | Damped Rotatory test Caloric cVEMP |

Moderate-low | Not assessed |

|

| Karltorp, 2014, Sweden22 | Case–control | 6 ScCMV 20 AcCMV 13 Controls (Cx26) |

26 SE (post-CI) cCMV 13 SE (post-CI) controls |

7.8 years | Movement ABC-2 Caloric vHIT cVEMP |

Moderate-Low | Visual acuity Ocular alignment Funduscopy |

|

| Laccourreye, 2015, France18 | R Cohort | 15 cCMV | 15 PR (pre-CI) | 14–36 months | Caloric | Moderate-low | Investigation not specified |

|

| Maes, 2017, Belgium21 | Cross-sectional | 16 ScCMV 8 AcCMV 8 cCMV negative controls 8 Cx26 |

8 ScCMV (R ear 80 dB SD 27; L ear 68.8 SD 39.3)* 0 using CI |

6.7 months | cVEMP | Moderate | Visual-motor integration (Peasbody Developmental Motor Scale) |

|

| Pappas, 1983, USA24 | Case–control | 19 AcCMV 17 cCMV negative controls |

14 (1 MI, 1 MO, 12 SE/PR) CI use not reported |

41 months | Caloric | Moderate–low | Not assessed |

|

| Paul, 2017, France16 | R Cohort | 3 ScCMV 5 AcCMV |

8 (2 MO, 6 PR/total HL) CI use not reported |

18 months | Canal and otolithic tests | Moderate-low | Not reported |

|

| Pinninti, 2021, USA11 | Case–control | 40 AcCMV 33 cCMV negative controls |

7 (2 MI, 2 MO/SE, 2 PR, 1 not reported) CI use not reported |

7.52 years | Rotatory test SVV cDVA cVEMP SOT BOT-2 |

Moderate | Vestibulo-visual tract Gaze stability |

|

| Strauss, 1985, USA9 | P Cohort | 6 ScCMV 5 AcCMV |

3 ScCMV (SE) CI use not reported |

22 months–8.5 years | Caloric | Low | Not assessed |

|

| Zagólski 2007, Poland10 | Case–control | 10 ScCMV 16 AcCMV 40 cCMV negative controls |

8 ScCMV ears (SE/PR) CI use not reported |

3 months | Caloric cVEMP |

Moderate | Not assessed |

|

Study design: R=retrospective; P=prospective.

Hearing loss=severity reported where available.

For mode of vestibular assessment, please see appendix A for glossary of vestibular and balance investigations.

Findings: (n)=number of cCMV cases out of N, where number of children tested is different to N, (n out of….) is reported.

*Where only mean decibel (dB) hearing threshold was reported, this can be interpreted as: <20 dB=normal; 21–40 dB=mild; 41–70 dB=moderate; 71–90 dB=severe; 91–119 dB=profound (Bernard, 2015).

†Range (where mean not reported).

ABC, assessment battery for children; AcCMV, asymptomatic cCMV; BOT-2, bruininks-oseretsky test of motor proficiency, second edition (BOT-2); cDVA, clinical dynamic visual acuity; CI, cochlear implant; cVEMP, cervical vestibular myogenic evoked potential; Cx26, connexin 26 mutation; EVAR, earth vertical axis rotation; HL, hearing loss; MI, mild; MO, moderate; N, number of cCMV cases; NH, normal hearing; OVAR, off vertical axis rotation; oVEMP, ocular vestibular myogenic evoked potential; P, prospective; PR, profound; R, retrospective; ScCMV, symptomatic CMV; SE, severe; SOT, sensory organisation test; SVV, subjective visual vertical; vHIT, video head impulse testing; VOR, vestibulo-ocular reflex.

Table 2.

Characteristics and findings of the eligible studies that performed non-vestibular specific balance assessments

| First author, year, country | Study design | N | N with hearing loss (HL) | Age (mean) | Mode of balance assessment | STROBE quality | Vision assessment | Findings |

| Alarcon, 2013, Spain26 | M cohort | 26 ScCMV | 17 (severity not specified) CI use not reported |

8.7 years | Movement ABC-2 |

Moderate | Not specified |

|

| De Kegel, 2015, Belgium28 | Case–control | 26 ScCMV 38 AcCMV 107 cCMV negative controls |

19 (ScCMV 83.2 dB; AcCMV 94.0 dB)* 9 using CI |

24 months | Ghent Developmental Balance Test | Moderate–low | Not reported |

|

| Harris, 1984, USA25 | P cohort | 50 cCMV | 5 (1 MI, 4 total) CI use not reported |

3 months | Traction response test | Moderate–low | Ophthalmological examination |

|

| Korndewal, 2017, Netherlands27 |

R cohort | 26 ScCMV 107 AcCMV |

2 ScCMV 3 AcCMV (2 ears MO, 1 ear SE, 4 ears PR) CI use not reported |

5 years, 6 months | Movement ABC Physical therapist report |

Moderate | Ophthalmological examination. Optometrist examination. |

|

Study design: R=retrospective, P=prospective, M=mixed (retrospective and prospective)

Hearing loss=severity reported where available.

Mode of balance assessment please see appendix A for glossary of vestibular and balance investigations.

Findings: (n)=number of cCMV cases out of N; where number of children tested is different to N, (n out of….) is reported.

*Where only mean decibel (dB) hearing threshold was reported, this can be interpreted as: <20 dB=normal; 21–40 dB=mild; 41–70 dB=moderate; 71–90 dB=severe; 91–119 dB=profound (Bernard, 2015).

ABC, assessment battery for children; AcCMV, asymptomatic cCMV; CI, cochlear implant; M, mixed (retrospective and prospective); MI, mild; MO, moderate; N, number of cCMV cases; P, prospective; PR, profound; r, Retrospective; ScCMV, symptomatic CMV; SE, severe; STROBE, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.

All 16 studies were published between 1984 and 2021 and conducted in high-income countries: France (3), Belgium (4), USA (4), Japan (1), Sweden (1), Spain (1), Poland (1) and the Netherlands (1).

Quality of studies

The 16 studies that reported data on vestibular function and/or balance in children with cCMV had notable methodological heterogeneity. We used an abridged STROBE statement, in the absence of a more optimal tool, to assess the quality of the studies.15 The quality ranged from moderate to low. Various definitions of vestibular dysfunction and balance impairment were reported. The 12 studies that performed vestibular-specific assessments had small sample sizes ranging from 8 to 93, making meaningful statistical analysis impossible.

Prevalence of vestibular dysfunction

The prevalence of vestibular dysfunction ranged from 14% to 90.4% across 12 studies using vestibular-specific assessments. Six cohort studies had a total of 187 study participants with cCMV, of whom 43.3% (81/187) had vestibular dysfunction. Four of six cohort studies had 15 or less participants. Vestibular dysfunction was reported in 25% (2/8; canal and otolithic tests) by Paul et al, 50% (3/6; caloric) by Strauss, 67% (4/6; cVEMP) by Inoue et al and 80% (12/15; caloric) by Laccourreye et al.9 16–18

Dhondt et al found 14% (13/93) had vestibular dysfunction, whereas Bernard et al found 90.4% (47/52) had vestibular dysfunction.19 20 Bernard’s study population were older (mean age 34.7 months vs 7.2 months), had a higher proportion of hearing loss (92.3% vs 18.3%) and underwent a more comprehensive battery of vestibular tests.

Three studies reported vestibular outcomes for children with symptomatic cCMV and asymptomatic cCMV (ie, normal clinical examinations, hearing, funduscopy, blood tests and neural imaging at birth) separately. Vestibular dysfunction was more than twice as frequently reported in children with symptomatic cCMV (up to 60%; 12/20 ears) compared with those with asymptomatic cCMV (up to 12.5%; 4/32 ears).10 19 21

Nature of vestibular dysfunction

The variety of vestibular-specific assessments used among the 12 studies indicate that dysfunction can affect various parts of the peripheral vestibular system and can be unilateral or bilateral. Zagólski demonstrated vestibular dysfunction can be detected as early as 3 months of age through caloric testing and cVEMP.10 Prevalence of vestibular dysfunction ranged between 44.7% (17/38) and 90.4% (47/52) in the studies that performed caloric testing and/or cVEMP in children older than 12 months.11 20 Only two studies undertook follow-up; Dhondt et al found that vestibular function deteriorated in 10% (6/61) in children (mean age 7.2 months) over a mean period of 10 months and Bernard et al found vestibular function deteriorated in 50% (7/14) in children (mean age 34.7 months) over 26.3 months.19 20

Children with SNHL formed ≥50% of the study population in eight out of the thirteen studies. Maes et al 21 found that 57% (4/7) of children with symptomatic cCMV and SNHL had vestibular dysfunction; however, vestibular dysfunction also occurred in children with normal hearing (1/7). Although the side and severity of vestibular dysfunction were significantly associated with the side and severity of SNHL, Bernard et al 20 did not find any concordance in those associations. Dhondt et al 19 also found a significant association between the presence of SNHL and the occurrence of vestibular dysfunction, but there was no association between vestibular dysfunction and the onset or the side of the SNHL.

Vestibular dysfunction may occur post cochlear implantation, which is a potential confounding factor. Karltorp et al 22 reported that 90% (9/10) of children using cochlear implants had abnormal vestibular function. Inoue et al, Laccoureye et al and Dhondt et al found that vestibular dysfunction can occur in the presence of severe-profound hearing loss prior to cochlear implant surgery,17 18 23 with a prevalence of vestibular dysfunction between 40% (2/5) and 80% (12/15).

Pinninti et al and Pappas et al reported a vestibular dysfunction prevalence of between 44.7% (17/38) and 63.6% (7/11) in children with asymptomatic cCMV, even in the context of normal hearing, compared with children without CMV (who had normal hearing).11 24

Prevalence of balance disturbance

Harris et al 25 found 9% (4/43) of infants with cCMV had transient signs of head imbalance through traction response testing. Alarcon et al and Korndewal et al reported balance disturbance affecting between 6% (8/133) and 27% (3/11) in children with cCMV.26 27 None of those studies performed vestibular-specific assessments. De Kegel et al 28 found that children with symptomatic cCMV had significantly worse balance when compared with children who had asymptomatic cCMV.

Pinninti et al 11 found 50% (20/40) of children with asymptomatic cCMV had difficulties maintaining balance but just 17.5% (7/40) had hearing impairment.

Discussion

This paper is the first systematic review of vestibular function in children with cCMV. The prevalence of vestibular dysfunction in children with cCMV is significant but difficult to quantify due to small single centre studies, variation in vestibular assessment and limited long-term follow-up of patients. Vestibular dysfunction was more common in children with symptomatic than asymptomatic cCMV but was identified in children both with and without hearing loss.10 11 21 24 Vestibular dysfunction in children with cCMV was reported to deteriorate over 10–26 months.19 20 Balance in children with cCMV was significantly worse than their peers.28

The exact mechanism by which CMV causes vestibular dysfunction is not clearly defined. Cytomegalic cells, loss of hair cells and degeneration of nerve fibres have been reported in the semicircular canals and otolith organs in the vestibular system.7 Dual pathology could potentially occur; however, high-resolution CT temporal bone imaging has not shown any anatomical abnormalities of the vestibular apparatus such as enlarged vestibular aqueducts in children with cCMV.29 30

It was not possible to obtain an accurate prevalence of cCMV-related vestibular dysfunction, as children with symptomatic cCMV and/or hearing loss are overrepresented in this evidence base. There is currently no universal screening programme for cCMV, and therefore, asymptomatic neonates are often not diagnosed or followed up in clinic. Similarly, children who present with balance problems, developmental delay or cerebral palsy may not have been investigated for cCMV if they have normal hearing.

Vestibular dysfunction resulting in gross motor delay may also contribute to learning difficulties and other neurodevelopmental disabilities. Visual and hearing impairment are known sequela of cCMV, and concurrent vestibular dysfunction leads to triple sensory loss in affected children. One study found out of 34 children with cCMV using cochlear implants, parents reported 26% had movement difficulties linked with balance and 15% had visual difficulties.31 Retrospective dried blood spot studies have reported a prevalence of cCMV of 9.6% (31/323) in children with cerebral palsy and of 5.6% (2/38) in children with autism.32 33 Vestibular dysfunction can occur in children with cerebral palsy, and vestibular stimulation has been reported to improve their motor function.34–36

Further work needs to be undertaken to improve cCMV diagnoses in children with balance problems and gross motor delay and enable children with cCMV to access beneficial services. Future research priorities should include a universal screening study for cCMV, to identify symptomatic and asymptomatic neonates and healthy controls for a longitudinal study. Long-term follow-up involving a battery of tests to comprehensively evaluate vestibular function and balance, and controlling for effects of cochlear implantation, would provide a more accurate measure of vestibular dysfunction in children with cCMV. A multinational registry to collect long-term follow-up on several parameters including vestibular dysfunction is planned (cCMVnet); this would help advise parents, inform patient services and identify key questions for future treatment trials. A retrospective study testing for cCMV in stored dried blood spots samples of children attending vestibular, balance or developmental delay clinics could better delineate the contribution of cCMV in these conditions. Qualitative data on quality of life captured from children with cCMV and their families would inform and improve services.

Recommendations for clinical practice

Neonatologists, paediatricians and audiovestibular physicians should continue to follow neonates with cCMV closely during early childhood to observe for vestibular dysfunction in addition to other neurodevelopmental issues. A list of screening tools for vestibular dysfunction in the paediatric clinic is described in online supplemental appendix C. Clinicians should have a low threshold for referral to regional audiovestibular services. CMV tests, including the dried blood spot, should be considered for children presenting with vestibular dysfunction, balance disorder and gross motor delay.

fetalneonatal-2021-323380supp003.pdf (63KB, pdf)

Parents of children with cCMV should be counselled regarding the variable long-term outcomes for hearing, balance, gross motor development and vision. Early detection of cCMV helps to facilitate timely investigations and early supportive interventions such as hearing aids, physiotherapy and multidisciplinary follow-up.

Diagnosis of vestibular dysfunction in children with cCMV is important, as interventions such as vestibular-focused rehabilitation may improve balance.13 37 This can potentially improve quality of life, aid developmental progress and improve motor function. Further research into the benefits of paediatric vestibular-focused rehabilitation is needed.

Diagnosis of vestibular dysfunction also enables the child and parent(s) to have their health problem recognised and validated. Safety advice regarding swimming and riding a bicycle, particularly in the dark, which rely more on vestibular inputs, should be given to improve safety.

Conclusions

This systematic review has found vestibular dysfunction to be a common sequela of cCMV. It can occur in children who were asymptomatic at birth and in children with normal hearing. Balance disorder affects gross motor development, coordination and quality of life. Balance should be explored as part of routine clinical reviews, with use of vestibular screening tools to guide referral for testing. Vestibular function is an important outcome to measure when investigating the benefits of cCMV screening and of antiviral treatment. Large-scale collaborative research is needed to better understand vestibular function and balance in children with cCMV, using a test battery that tests both semicircular canal and otolith organs, includes quality of life measures and the effects of vestibular physiotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Evidence search: Vestibular function in infants/children with congenital cytomegalovirus. Igor Brbre. (5th April, 2019; 22nd March 2021). BRIGHTON, UK: Brighton and Sussex Library and Knowledge Service.

Footnotes

Twitter: @GeorginaYan

AS and GY contributed equally.

Contributors: AS, KF, SS, SK, PH, SW and SL conceived the project. AS, KF and EC designed the protocol. AS, GY and HM acquired the data. GY analysed the data with input from AS, KF and SW. GY, AS, SW and KF drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed to its development and approved the final manuscript. KF is reponsibe for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol 2007;17:253–76. 10.1002/rmv.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 2007;17:355–63. 10.1002/rmv.544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ssentongo P, Hehnly C, Birungi P, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection burden and epidemiologic risk factors in countries with universal screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2120736. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dreher AM, Arora N, Fowler KB, et al. Spectrum of disease and outcome in children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatr 2014;164:855–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huygen PL, Admiraal RJ, Admiraal RJC. Audiovestibular sequelae of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in 3 children presumably representing 3 symptomatically different types of delayed endolymphatic hydrops. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1996;35:143–54. 10.1016/0165-5876(96)83899-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janky KL, Rodriguez AI. Quantitative vestibular function testing in the pediatric population. Semin Hear 2018;39:257–74. 10.1055/s-0038-1666817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsuprun V, Keskin N, Schleiss MR, et al. Cytomegalovirus-Induced pathology in human temporal bones with congenital and acquired infection. Am J Otolaryngol 2019;40:102270. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Teissier N, Bernard S, Quesnel S, et al. Audiovestibular consequences of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2016;133:413–8. 10.1016/j.anorl.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Strauss M. A clinical pathologic study of hearing loss in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Laryngoscope 1985;95:951–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zagólski O. Vestibular-Evoked myogenic potentials and caloric stimulation in infants with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Laryngol Otol 2008;122:574–9. 10.1017/S0022215107000412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pinninti S, Christy J, Almutairi A, et al. Vestibular, gaze, and balance disorders in asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 2021;147:e20193945. 10.1542/peds.2019-3945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shears A, Fidler K, Luck S, et al. Routine vestibular function assessment in children with congenital CMV: are we ready? Hear J 2021;74:14. 10.1097/01.HJ.0000752304.01935.cb [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rine RM, Braswell J, Fisher D, et al. Improvement of motor development and postural control following intervention in children with sensorineural hearing loss and vestibular impairment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2004;68:1141–8. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JPT. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:666–76. 10.1093/ije/dym018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paul A, Marlin S, Parodi M, et al. Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss: medical context and etiology. Audiol Neurootol 2017;22:83–8. 10.1159/000474928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inoue A, Iwasaki S, Ushio M, et al. Effect of vestibular dysfunction on the development of gross motor function in children with profound hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol 2013;18:143–51. 10.1159/000346344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laccourreye L, Ettienne V, Prang I, et al. Speech perception, production and intelligibility in French-speaking children with profound hearing loss and early cochlear implantation after congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2015;132:317–20. 10.1016/j.anorl.2015.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dhondt C, Maes L, Rombaut L, et al. Vestibular function in children with a congenital cytomegalovirus infection: 3 years of follow-up. Ear Hearing 2021;42:76–86. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bernard S, Wiener-Vacher S, Van Den Abbeele T, et al. Vestibular disorders in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 2015;136:e887–95. 10.1542/peds.2015-0908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maes L, De Kegel A, Van Waelvelde H, et al. Comparison of the motor performance and vestibular function in infants with a congenital cytomegalovirus infection or a connexin 26 mutation: a preliminary study. Ear Hear 2017;38:e49–56. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karltorp E, Löfkvist U, Lewensohn-Fuchs I, et al. Impaired balance and neurodevelopmental disabilities among children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:1165–73. 10.1111/apa.12745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dhondt C, Maes L, Oostra A, et al. Episodic vestibular symptoms in children with a congenital cytomegalovirus infection: a case series. Otol Neurotol 2019;40:e636–42. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pappas DG. Hearing impairments and vestibular abnormalities among children with subclinical cytomegalovirus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1983;92:552–7. 10.1177/000348948309200604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harris S, Ahlfors K, Ivarsson S, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection and sensorineural hearing loss. Ear Hear 1984;5:352–5. 10.1097/00003446-198411000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alarcon A, Martinez-Biarge M, Cabañas F, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and neuroimaging findings predict long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatr 2013;163:828–34. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Korndewal MJ, Oudesluys-Murphy AM, Kroes ACM, et al. Long-Term impairment attributable to congenital cytomegalovirus infection: a retrospective cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2017;59:1261–8. 10.1111/dmcn.13556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Kegel A, Maes L, Dhooge I, et al. Early motor development of children with a congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Res Dev Disabil 2016;48:253–61. 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pryor SP, Demmler GJ, Madeo AC, et al. Investigation of the role of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in the etiology of enlarged vestibular aqueducts. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;131:388–92. 10.1001/archotol.131.5.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Madden C, Wiley S, Schleiss M, et al. Audiometric, clinical and educational outcomes in a pediatric symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) population with sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2005;69:1191–8. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Inscoe JR, Bones C. Additional difficulties associated with aetiologies of deafness: outcomes from a parent questionnaire of 540 children using cochlear implants. Cochlear Implants Int 2016;17:21–30. 10.1179/1754762815Y.0000000017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smithers-Sheedy H, Raynes-Greenow C, Badawi N, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus among children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr 2017;181:267–71. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gentile I, Zappulo E, Riccio MP, et al. Prevalence of congenital cytomegalovirus infection assessed through viral genome detection in dried blood spots in children with autism spectrum disorders. In Vivo 2017;31:467–73. 10.21873/invivo.11085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tramontano M, Medici A, Iosa M, et al. The effect of vestibular stimulation on motor functions of children with cerebral palsy. Motor Control 2017;21:299–311. 10.1123/mc.2015-0089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rose J, Wolff DR, Jones VK, et al. Postural balance in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2002;44:58–63. 10.1017/S0012162201001669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Almutairi A, Cochrane GD, Christy JB. Vestibular and oculomotor function in children with CP: descriptive study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2019;119:15–21. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rine RM. Vestibular rehabilitation for children. Semin Hear 2018;39:334–44. 10.1055/s-0038-1666822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

fetalneonatal-2021-323380supp001.pdf (81.9KB, pdf)

fetalneonatal-2021-323380supp002.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

fetalneonatal-2021-323380supp003.pdf (63KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.