Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of upadacitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (AS) with an inadequate response (IR) to biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs).

Methods

Adults with active AS who met modified New York criteria and had an IR to one or two bDMARDs (tumour necrosis factor or interleukin-17 inhibitors) were randomised 1:1 to oral upadacitinib 15 mg once daily or placebo. The primary endpoint was Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 40 (ASAS40) response at week 14. Sequentially tested secondary endpoints included Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity score, Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada MRI spine inflammation score, total back pain, nocturnal back pain, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index and Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score. Results are reported from the 14-week double-blind treatment period.

Results

A total of 420 patients with active AS were randomised (upadacitinib 15 mg, n=211; placebo, n=209). Significantly more patients achieved the primary endpoint of ASAS40 at week 14 with upadacitinib vs placebo (45% vs 18%; p<0.0001). Statistically significant improvements were observed with upadacitinib vs placebo for all multiplicity-controlled secondary endpoints (p<0.0001). Adverse events were reported for 41% of upadacitinib-treated and 37% of placebo-treated patients through week 14. No events of malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism or deaths were reported with upadacitinib.

Conclusion

Upadacitinib 15 mg was significantly more effective than placebo over 14 weeks of treatment in bDMARD-IR patients with active AS. No new safety risks were identified with upadacitinib.

Trial registration number

Keywords: spondylitis, ankylosing; antirheumatic agents; inflammation; Magnetic Resonance Imaging

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Advanced treatment options for ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are mainly limited to biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), such as tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) and interleukin-17 inhibitors (IL-17i).

Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi-) have recently emerged as alternative, oral treatment options for active AS based on clinical trials conducted in AS bDMARD-naïve patients.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The SELECT-AXIS 2 AS bDMARD-inadequate response (IR) study is the first clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a JAKi in an active AS bDMARD-IR population, including patients with an IR to IL-17i.

Upadacitinib 15 mg significantly improved the signs and symptoms of active AS and was well tolerated for 14 weeks of treatment in bDMARD-IR patients, consistent with results observed in the upadacitinib AS bDMARD-naïve study.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Upadacitinib 15 mg offers an effective treatment option for bDMARD-naïve and bDMARD-IR patients with active AS.

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory condition that encompasses non-radiographic axSpA and radiographic axSpA, also known as ankylosing spondylitis (AS).1–3 AxSpA is characterised by inflammatory back pain4–6 and other symptoms including spinal mobility or functional impairments, peripheral and extra-musculoskeletal manifestations, diminished quality of life and loss of work productivity.1 6–9

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first-line pharmacological therapy for axSpA.10 11 Treatment with a biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD), such as a tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) or an interleukin-17 inhibitor (IL-17i), is recommended in patients who do not sufficiently respond to NSAIDs. However, many patients do not achieve desired treatment goals, including low disease activity, with bDMARD therapy.12–15 Overall, treatment options for axSpA remain limited compared with other rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or psoriatic arthritis (PsA), also given that conventional synthetic DMARDs or long-term corticosteroids are ineffective for treating axial symptoms.10 11 Growing evidence supports the benefit of Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) as an effective oral therapy for the treatment of active AS.16–20

Upadacitinib 15 mg once daily, an oral JAKi, demonstrated sustained efficacy and was well tolerated for up to 2 years in bDMARD-naïve patients with AS in the SELECT-AXIS 1 trial.21–23 To date, no dedicated studies of JAKi treatment in an AS population with an inadequate response (IR) to bDMARD therapy have been conducted. SELECT-AXIS 2 was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of upadacitinib 15 mg once daily vs placebo in a bDMARD-IR AS population, including patients with an IR to IL-17i.

Methods

Study design

SELECT-AXIS 2 (NCT04169373) was conducted using a master protocol (details provided in online supplemental methods). The AS bDMARD-IR study includes a 35-day screening period followed by a 14-week, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled treatment period and a 90-week open-label extension period (figure 1). Here, we present the primary 14-week results from the AS bDMARD-IR study.

Figure 1.

Study design. Study design of the AS bDMARD-IR study of the SELECT-AXIS 2 master protocol is illustrated. *Patients in remission at week 104 could enter a remission-withdrawal period until flare or week 152. AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASAS40, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 40 response; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; IR, inadequate response; QD, once daily; SI, sacroiliac.

ard-2022-222608supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patients

Eligible patients were adults (aged ≥18 years) who had an AS diagnosis and fulfilled modified New York criteria based on central reading of sacroiliac joint radiographs. Patients had active disease at the screening and baseline visits defined as a Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score and a patient’s assessment of total back pain score of ≥4 on a 0–10 scale, an IR to ≥2 NSAIDs or intolerance to or contraindication for NSAIDs, and an IR to bDMARD therapy. In this study, an IR to bDMARD therapy was defined as patients who discontinued bDMARD therapy (TNFi or IL-17i) due to lack of efficacy (after ≥12 weeks of treatment at an adequate dose) based on the investigators’ assessment or intolerance (irrespective of treatment duration). Prior exposure to two bDMARDs was allowed for no more than 30% of patients; among patients with prior exposure to two bDMARDs, a lack of efficacy to one bDMARD and intolerance to another was permitted, but a patient could not have a lack of efficacy to two bDMARDs. Patients receiving concomitant oral corticosteroids or NSAIDs must have been on a stable dose for at least 14 days prior to the baseline visit, while those receiving concomitant conventional synthetic DMARDs were required to be on a stable dose for at least 28 days prior to the baseline visit. Patients who were previously exposed to a JAKi or had total spinal ankylosis, which for the purpose of this study was defined as bridging syndesmophytes (fusion) in a total sum of ≥5 C2–T1 or T12–S1 spine segments, were excluded.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomised (1:1) to receive either blinded oral upadacitinib 15 mg once daily or placebo for 14 weeks using interactive response technology. Dose selection for upadacitinib 15 mg once daily was based on favourable results from the SELECT-AXIS 1 AS bDMARD-naïve study, including exposure-response analyses.21 24 Randomisation was stratified by screening high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP; ≤ or > upper limit of normal of 2.87 mg/L), class of prior bDMARD use (one TNFi, one IL-17i or two bDMARDs) and geographical region. The sponsor, investigators, study site personnel and the patients were blinded to the treatment assignments.

Procedures

Study visits occurred at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 14. MRI of the spine and sacroiliac joints was performed during the screening period prior to or at the baseline visit and week 14 visit. MRIs were independently assessed by two readers blinded to treatment allocation and imaging time points. Discrepancies between the readers were resolved through adjudication by a third reader if scoring differences exceeded a certain mean absolute difference threshold (details provided in online supplemental methods).21 The average scores of the two readers or the average of the two closest scores of the three readers in adjudicated cases were used to calculate MRI spine and sacroiliac joint inflammation scores. Radiographs of the sacroiliac joints were obtained during the screening period and centrally read (modified New York criteria) for eligibility purposes by two readers and an adjudicator in case of discrepancy; additionally, radiographs of the spine were obtained.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society 40 (ASAS40) response at week 14.25 Multiplicity-controlled secondary endpoints assessed at week 14 included changes from baseline in Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score based on CRP (ASDAS (CRP))26 and Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) MRI spine inflammation score,27 BASDAI50, ASAS20, ASDAS inactive disease (ID; score <1.3), ASDAS low disease activity (LDA; score <2.1),26 ASAS partial remission (absolute score of ≤2 units for each of the four domains of ASAS40), and changes from baseline in the following outcomes: patient’s assessment of total back pain, patient’s assessment of nocturnal back pain, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL), ASAS Health Index, Linear Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) and Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score (MASES) (online supplemental figure 1). Other efficacy endpoints included ASDAS major improvement (≥2 point-decrease from baseline), ASDAS clinically important improvement (≥1.1 point-decrease from baseline), and changes from baseline in ASAS and ASDAS components,25 SPARCC MRI sacroiliac joint inflammation score,28 tender/swollen joint counts and the six questions of the BASDAI.

Safety outcomes were reported with an onset of up to week 14 and included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and laboratory assessments. TEAEs were defined as adverse events (AEs) with an onset after the first dose of study drug and prior to the week 14 dose date or up to 30 days after the last dose of study drug if discontinued prematurely before week 14.

Statistical analysis

A planned sample size of 386 patients was estimated to provide ≥90% power for testing the superiority of upadacitinib to placebo for the primary endpoint of ASAS40 at week 14. The assumed response rates were 24% for upadacitinib and 6% for placebo.12 21 29 Power and sample size estimations were calculated using a two-sided significance level of 0.05 based on a 10% dropout rate. Efficacy analyses were performed based on randomised treatment using the full analysis set, which included all randomised patients who received at least one dose of study drug. The primary endpoint was also analysed in the per-protocol population. Safety analyses were conducted using the safety analysis set based on actual treatment received in patients who had at least one dose of study drug. For binary efficacy endpoints, response rates were compared between treatment groups using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, adjusting for the stratification factor of screening hsCRP level. Non-responder imputation incorporating multiple imputation (NRI-MI) was used to handle missing data and intercurrent events. Patients who prematurely discontinued the study drug were treated as non-responders. Missing data due to COVID-19 infection or logistical restriction were handled by MI. Additional missing data due to other reasons were categorised as non-responders for study visits. For continuous efficacy endpoints, mean changes from baseline were compared between treatment groups using a mixed-effect model for repeated measures or the analysis of covariance method. A sequential multiple testing procedure was conducted for all primary and multiplicity-controlled secondary endpoints, controlling the overall type I error rate at the two-sided significance level of 0.05 (online supplemental figure 1). Post hoc subgroup analyses were performed for the primary endpoint by the number (one or two) and type of previous bDMARDs (TNFi vs IL-17i) used.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

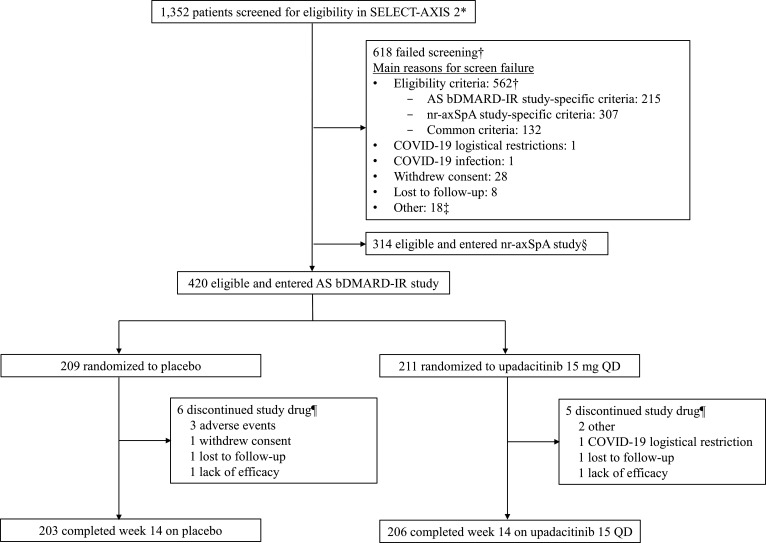

A total of 420 patients from 119 sites in 22 countries were enrolled in the AS bDMARD-IR study and randomly assigned to receive upadacitinib 15 mg once daily (n=211) or placebo (n=209) (figure 2, online supplemental table 1). Of these 420 patients, 206 (98%) on upadacitinib and 203 (97%) on placebo completed the 14-week double-blind treatment period. The most common primary reasons for premature discontinuation of study drug were AEs in the placebo group (n=3; 1%) and other reasons in the upadacitinib group (n=2; 1%).

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. *Patients were screened between 26 November 2019 and 20 May 2021, for the SELECT-AXIS 2 master protocol, which used a common screening platform to assign patients either to the AS bDMARD-IR study or nr-axSpA study. †Patients could have multiple criteria or multiple reasons for screening failure. Details of screen failure due to study eligibility criteria are presented in online supplemental table 1). ‡Other reasons included imaging, site, or system issues. §Patients did not fail screening (master protocol details provided in online supplemental methods). ¶Primary reason for discontinuation provided. AS, ankylosing spondylitis; bDMARD, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; IR, inadequate response; nr-axSpA, non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis; QD, once daily.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics were generally balanced between treatment groups and reflective of an active AS bDMARD-IR population (table 1). Most patients had prior exposure to one TNFi (74%) followed by one IL-17i (13%), two TNFi (8%), one TNFi and one IL-17i (5%) and two IL-17i (0.5%); 77% of patients discontinued prior bDMARD therapy because of lack of efficacy and 30% because of intolerance. Approximately one-third of patients (31%) used conventional synthetic DMARDs at baseline.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=209) | Upadacitinib 15 mg once daily (n=211) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 158 (76%) | 153 (73%) |

| Female | 51 (24%) | 58 (27%) |

| Age, years | 42.2 (11.8) | 42.6 (12.4) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.4 (5.0) | 27.2 (5.7) |

| Race | ||

| White | 169 (81%) | 168 (80%) |

| Asian | 37 (18%) | 42 (20%) |

| African American | 3 (1%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Region | ||

| North America | 25 (12%) | 25 (12%) |

| South/Central America | 14 (7%) | 13 (6%) |

| Western Europe | 25 (12%) | 16 (8%) |

| Eastern Europe | 98 (47%) | 109 (52%) |

| Asia* | 34 (16%) | 41 (19%) |

| Other† | 13 (6%) | 7 (3%) |

| HLA-B27 positive | 168 (81%) | 180 (85%) |

| Time since AS diagnosis, years | 7.5 (7.5) | 7.9 (7.5) |

| Time of AS symptoms, years | 12.6 (9.3) | 12.9 (9.1) |

| Baseline medication use | ||

| NSAIDs | 163 (78%) | 163 (77%) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 18 (9%) | 27 (13%) |

| csDMARDs | 62 (30%) | 68 (32%) |

| Prior bDMARD use‡ | ||

| One TNFi | 158 (76%) | 154 (73%) |

| Two TNFi | 14 (7%) | 19 (9%) |

| One IL-17i | 24 (11%) | 29 (14%) |

| Two IL-17i | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| One TNFi and one IL-17i | 11 (5%) | 8 (4%) |

| Total back pain (0–10 NRS)§ | 7.4 (1.4) | 7.5 (1.5) |

| Nocturnal back pain (0–10 NRS)¶ | 7.2 (1.5) | 7.1 (1.8) |

| Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (0–10 NRS) | 7.2 (1.4) | 7.4 (1.5) |

| Morning stiffness (0–10 NRS)** | 6.8 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.8) |

| ASDAS (CRP) | 3.9 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.8) |

| BASDAI score | 6.8 (1.3) | 6.8 (1.3) |

| BASFI score | 6.2 (1.9) | 6.3 (2.0) |

| BASMI score | 3.9 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.6) |

| Enthesitis | 162 (78%) | 148 (70%) |

| MASES score†† | 4.2 (3.1) | 4.9 (3.0) |

| SPARCC MRI spine score‡‡ | 8.8 (12.5) | 10.7 (15.4) |

| SPARCC MRI sacroiliac joint score‡‡ | 5.6 (10.6) | 5.0 (10.8) |

| hsCRP at screening, mg/L | 14.5 (17.8) | 15.8 (17.7) |

| hsCRP >ULN (2.87 mg/L) at screening | 163 (78%) | 165 (78%) |

| ASQoL§§ | 11.5 (4.4) | 11.6 (4.4) |

| ASAS Health Index¶ | 8.9 (3.7) | 9.4 (3.5) |

| History of uveitis | 15 (7%) | 21 (10%) |

| History of IBD | 5 (2%) | 7 (3%) |

| History of psoriasis¶¶ | 7 (3%) | 7 (3%) |

Data are n (%) or mean (SD) unless noted otherwise.

*Patients were from China (n=32), Taiwan (n=21), Japan (n=12) and South Korea (n=10).

†Patients were from New Zealand (n=10), Australia (n=7) and Israel (n=3).

‡Categories for prior bDMARD use were mutually exclusive. One patient on placebo did not have prior bDMARD exposure.

§Total back pain was defined on a numerical rating scale (0–10) based on the question, ‘What is the amount of back pain that you experienced at any time during the last week?’.

¶Assessed n=208 in the placebo group.

**Morning stiffness was defined as the mean of questions 5 (severity of morning stiffness) and 6 (duration of morning stiffness) of the BASDAI.

††Assessed n=162 in the placebo group; and n=148 in the upadacitinib group with MASES >0 at baseline.

‡‡Assessed n=202 in the placebo group; and n=199 in the upadacitinib group with available baseline MRI data up to 3 days after the first dose of study drug.

§§Assessed n=208 in the placebo group; and n=210 in the upadacitinib group.

¶¶History of psoriasis was obtained based on 12 psoriasis-related preferred terms, including ‘psoriasis’.

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; bDMARDs, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; CRP, C-reactive protein; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic DMARDs; HLA-B27, human leucocyte antigen B27; hsCRP, high-sensitivity CRP; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IL-17i, interleukin-17 inhibitor; MASES, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SPARCC, Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Efficacy

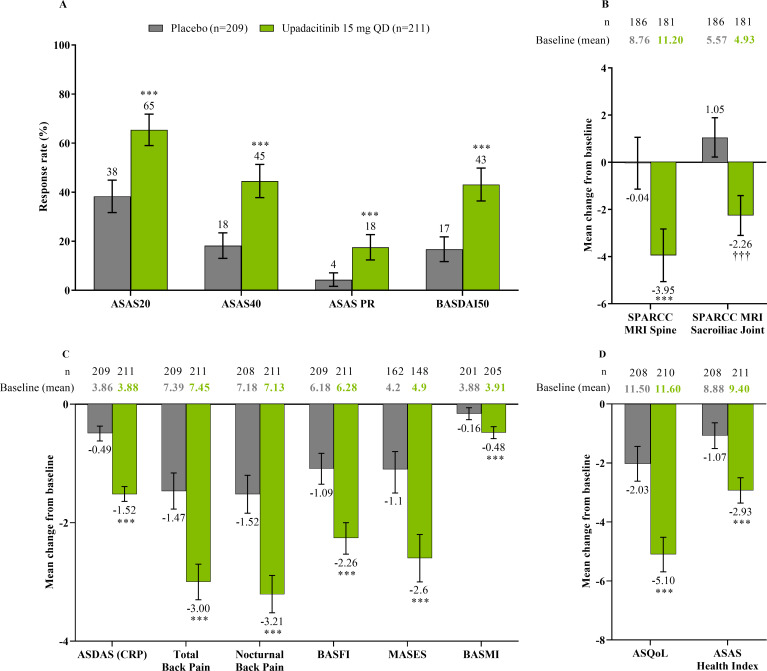

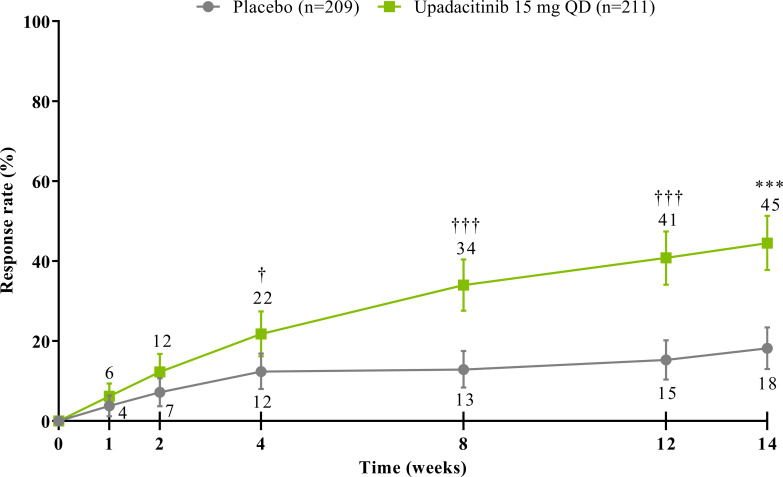

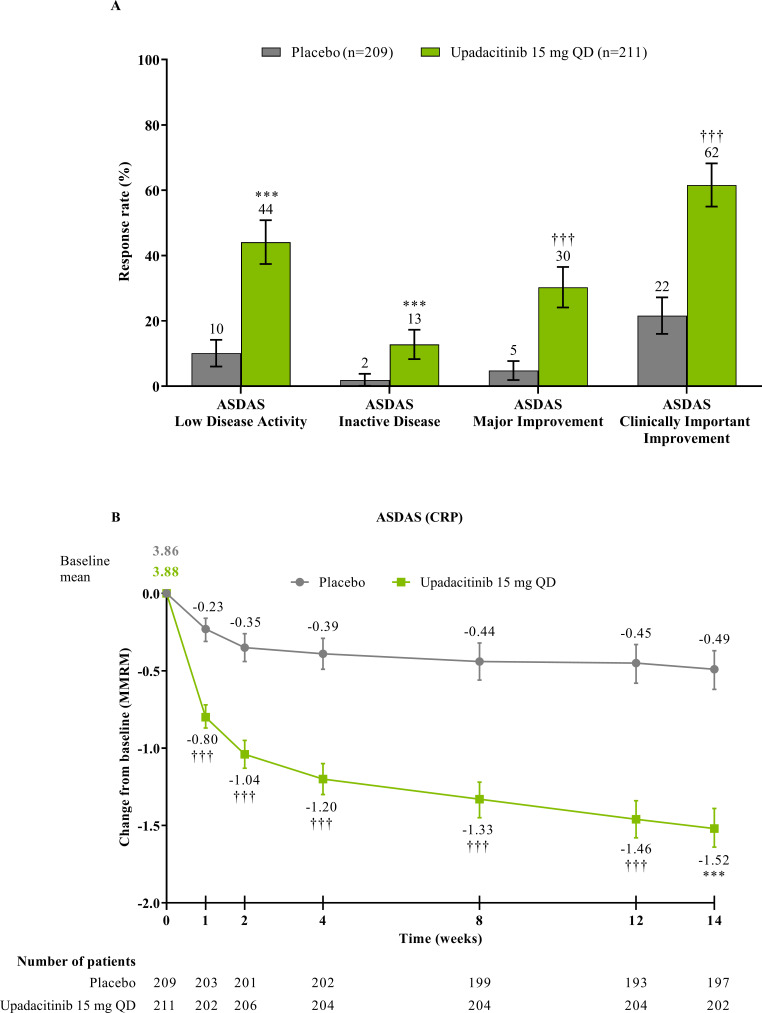

The study met its primary and all multiplicity-controlled secondary endpoints at week 14 (figure 3; online supplemental table 2). A significantly higher proportion of patients achieved the primary endpoint of ASAS40 at week 14 in the upadacitinib group vs the placebo group (45% vs 18%; p<0.0001) with a treatment difference of 26% (95% CI 18% to 35%). A clear separation between treatment groups was observed for ASAS40 starting at week 4 (nominal p≤0.05; figure 4). Consistent improvements were observed for the four ASAS components with greater improvement in the upadacitinib than the placebo group (nominal p≤0.05) from week 1 onwards for three of the four components and from week 4 onwards for BASFI (online supplemental figure 2). ASAS40 responses at week 14 were similar in the per-protocol analysis set (online supplemental figure 3). Greater ASAS40 treatment effects were also seen with upadacitinib vs placebo in the subgroups of patients treated with one (46% vs 20%) or two (36% vs 4%) prior bDMARDs; with previous exposure to TNFi (47% vs 22%) or IL-17i (37% vs 4%; online supplemental figure 4); and with baseline hsCRP of ≤ or > 2.78 mg/L (52% vs 15% and 42% vs 19%, respectively) and ≤ or > 5 mg/L (47% vs 15% and 44% vs 20%, respectively; online supplemental figure 5). ASAS40 response rates were consistent between Eastern European (50% vs 19%) and non-Eastern European patients (39% vs 17%) treated with upadacitinib vs placebo (online supplemental figure 6). Statistically significant improvements in disease activity, function and pain were achieved among upadacitinib-treated vs placebo-treated patients at week 14, as measured by change from baseline in ASDAS, total and nocturnal back pain, and BASFI, and achievement of ASDAS ID, ASDAS LDA, BASDAI50, ASAS20 and ASAS partial remission (p<0.0001; figure 3 A, C, figure 5, online supplemental figures 2B, 7, 8A). Consistent responses were observed for other patient-reported pain, ASDAS-related measures and BASDAI (figure 5A and online supplemental figures 8B-10). Upadacitinib also improved objective signs of inflammation as measured by hsCRP and SPARCC MRI spine and sacroiliac joint inflammation scores (p<0.0001 vs placebo; figure 3B, online supplemental figures 10B and 11). Other clinically relevant domains significantly improved with upadacitinib treatment vs placebo at week 14, including quality of life (ASQoL and ASAS Health Index), spinal mobility (BASMI) and enthesitis (MASES) (p<0.0001; figure 3C, D). Additional efficacy endpoints, including change from baseline in tender/swollen joint counts at week 14, are presented in online supplemental table 3.

Figure 3.

Multiplicity-controlled and key secondary endpoints at week 14. (A) ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS PR and BASDAI50 responses at week 14 based on NRI-MI analysis. (B) Change from baseline in SPARCC MRI spine and sacroiliac joint scores at week 14 based on ANCOVA analysis. SPARCC MRI was assessed in patients with available baseline MRI data up to 3 days after the first dose of study drug and available week 14 MRI data up to the first dose of study drug in the open-label period. (C) Additional multiplicity-controlled key secondary efficacy endpoints at week 14; ANCOVA analysis for BASMI and MMRM analysis for other endpoints. MASES was assessed in patients with baseline enthesitis. (D) Change from baseline in ASQoL and ASAS Health Index at week 14 based on MMRM analysis. ANCOVA/MMRM analyses are based on as observed data. All endpoints were multiplicity controlled and tested sequentially (online supplemental figure 1), except for SPARCC MRI sacroiliac joint score. Error bars show 95% CI. Significant in multiplicity-controlled analysis: ***p<0.0001. Without adjustment for multiplicity (nominal): ††† p<0.0001. ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASAS20, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 20 response; ASAS40, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 40 response; ASAS PR, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society partial remission; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ASQoL, Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Score; BASDAI50, at least 50% improvement from baseline in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; MASES, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score; MMRM, mixed-effect model for repeated measures; NRI-MI, non-responder imputation incorporating multiple-imputation; QD, once daily; SPARCC, Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada.

Figure 4.

ASAS40 response through week 14. NRI-MI analysis was used. Error bars show 95% CI. Significant in multiplicity-controlled analysis: ***p<0.0001. Without adjustment for multiplicity (nominal): †p<0.05; †††p<0.0001. ASAS40, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society 40 response; NRI-MI, non-responder imputation incorporating multiple imputation; QD, once daily.

Figure 5.

ASDAS responses at and through week 14. (A) Proportion of patients with ASDAS responses at week 14 was based on NRI-MI analysis. ASDAS low disease activity was defined as ASDAS (CRP) <2.1 and ASDAS inactive disease as ASDAS (CRP) <1.3. (B) Mean change from baseline in ASDAS (CRP) through week 14 was based on MMRM analysis, and the numbers of patients were as observed at each visit. Error bars show 95% CI. Significant in multiplicity-controlled analysis: ***p<0.0001. Without adjustment for multiplicity (nominal): †††p<0.0001. ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; CRP, C-reactive protein; MMRM, mixed-effect model for repeated measures; NRI-MI, non-responder imputation incorporating multiple-imputation; QD, once daily.

Safety

The rate of AEs during the 14-week double-blind treatment period was similar between the two treatment groups (41% with upadacitinib and 37% with placebo; table 2). Serious AEs were reported more frequently with upadacitinib (2.8%) than placebo (0.5%): one patient (0.5%) had acute cholangitis, and five (2.4%) patients had serious infections on upadacitinib (table 2). Four of the five serious infections on upadacitinib were COVID-19-related infections; all patients had risk factors for more severe disease30 including older age, male sex, hypertension or obesity, and all events resolved. Overall, COVID-19-related AEs, including the serious infections reported above, occurred in 17 patients (5.7% on upadacitinib vs 2.4% on placebo; online supplemental table 4). None of the 17 affected patients had to discontinue study drug treatment prematurely, and none were vaccinated against COVID-19 except one patient on upadacitinib with a non-serious asymptomatic COVID-19 AE. A numerically higher proportion of patients from Eastern Europe (5.3%) than non-Eastern Europe (3.3%) had a COVID-19-related AE; the four serious COVID-19-related AEs were reported in patients from Eastern Europe (online supplemental table 5). No deaths, opportunistic infections, non-melanoma skin cancer, lymphoma, adjudicated gastrointestinal perforation, renal dysfunction, active tuberculosis or adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular or venous thromboembolic events were reported through week 14 in either treatment group. Two non-serious events of herpes zoster (0.9%) on upadacitinib occurred in patients from Japan, were confined to a single dermatome, and did not lead to treatment discontinuation. One event of tonsil cancer (0.5%) was reported in a patient receiving placebo who was a former smoker, leading to discontinuation of study drug. No malignancy was reported with upadacitinib. Uveitis occurred in four patients (one (0.5%) patient on upadacitinib with a history of uveitis; three (1.4%) patients on placebo with two with a history of uveitis). One AE of Crohn’s disease was reported in a patient (0.5%) without a history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the upadacitinib group; no events of IBD were reported in the placebo group. An AE of psoriasis occurred in one patient (0.5%) without a history of psoriasis in the placebo group; no events were reported in the upadacitinib group.

Table 2.

Safety outcomes through week 14

| Placebo (n=209) |

Upadacitinib 15 mg once daily (n=211) | |

| Any AE | 77 (37%) | 86 (41%) |

| Serious AE | 1 (0.5%)* | 6 (2.8%)† |

| Discontinuation of study drug due to AE | 3 (1.4%)‡ | 0 |

| COVID-19-related AE§ | 6 (2.9%) | 12 (5.7%) |

| Death | 0 | 0 |

| Infection | 27 (12.9%) | 31 (14.7%) |

| Serious infection | 0 | 5 (2.4%)¶ |

| Opportunistic infection | 0 | 0 |

| Active tuberculosis | 0 | 0 |

| Herpes zoster | 0 | 2 (0.9%)** |

| Malignancy | 1 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Malignancy other than NMSC | 1 (0.5%)* | 0 |

| NMSC | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic disorder | 2 (1.0%) | 6 (2.8%)†† |

| Anaemia | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (1.4%)‡‡ |

| Neutropenia | 2 (1.0%) | 6 (2.8%)§§ |

| Lymphopenia | 2 (1.0%) | 1 (0.5%)¶¶ |

| Renal dysfunction | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal perforation (adjudicated) | 0 | 0 |

| Major adverse cardiovascular events (adjudicated) | 0 | 0 |

| Venous thromboembolic events (adjudicated) | 0 | 0 |

| Uveitis | 3 (1.4%)*** | 1 (0.5%)††† |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0 | 1 (0.5%)‡‡‡ |

| Psoriasis§§§ | 1 (0.5%) | 0 |

Data are n (%).

*Tonsil cancer.

†COVID-19 (n=4), cholangitis (n=1) and uveitis (n=1).

‡One patient each with tonsil cancer, hip and back pain, inguinal hernia.

§As collected in the AE electronic case report form. An AE with the preferred term ‘urinary tract infection’ was incorrectly attributed to COVID-19 by the site. Therefore, five subjects in the placebo group had COVID-19-related AEs.

¶COVID-19 (n=4) and uveitis (n=1). All events resolved and were deemed by the investigators as having no reasonable possibility of being related to study drug.

**Two patients from Japan had non-serious herpes zoster confined to a single dermatome.

††ALT/AST elevations were transient, and study drug was not interrupted for patients receiving upadacitinib.

‡‡All anaemia events were non-serious and mild or moderate. Treatment with upadacitinib was interrupted in two patients in which events resolved with no treatment discontinuation.

§§All neutropenia events were non-serious: one was severe and five were mild or moderate. One patient interrupted upadacitinib but neutropenia resolved without study drug discontinuation.

¶¶Lymphopenia event was non-serious, mild, and did not lead to study drug interruption or discontinuation.

***Two patients had a history of uveitis.

†††One patient with a history of uveitis had recurrent uveitis that was considered as having no reasonable possibility of being related to study drug by the investigator.

‡‡‡One patient without a history of inflammatory bowel disease had a non-serious event of Crohn’s disease.

§§§AE of psoriasis was based on 12 psoriasis-related preferred terms, including ‘psoriasis’.

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; NMSC, nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Hepatic disorders in the upadacitinib group were mild or moderate transaminase elevations; none resulted in treatment discontinuation. Three patients had a grade 3 elevation in alanine aminotransferase (ALT; one patient (0.5%)) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST; two patients (0.9%)) levels with upadacitinib treatment. The patient with elevated ALT also experienced acute cholangitis as described above, concurrent with increased AST. No cases met the criteria of Hy’s law. During the 14-week double-blind treatment period, four patients temporarily interrupted study drug per the study protocol (three due to ALT/AST elevations and one due to a decrease of haemoglobin). Adverse events of anaemia, neutropenia and lymphopenia were generally mild or moderate, non-serious and did not lead to discontinuation of the study drug. Mean haemoglobin concentrations remained stable for both treatment groups, and changes in other laboratory values were generally transient (online supplemental figure 12). Five patients treated with upadacitinib had a grade three decrease in lymphocyte (0.5%) or neutrophil (1.9%) counts, which were not associated with serious infections.

Discussion

SELECT-AXIS 2 is the first clinical trial dedicated to evaluating the efficacy and safety of a JAKi in an AS population that had a lack of efficacy or were intolerant to bDMARDs, including TNFi or IL-17i. The study met its primary endpoint of ASAS40 response, and all ranked secondary endpoints at week 14, demonstrating the consistent benefit of upadacitinib 15 mg once daily relative to placebo for treating multiple clinically relevant domains and components of AS, including improvements in objective signs of axial inflammation. In addition, upadacitinib provided quick symptom relief as early as week 1.

Results of this study in a treatment-refractory AS patient population were consistent with and complementary to those of SELECT-AXIS 1, which evaluated upadacitinib in AS bDMARD-naïve patients.21 The responses in our study were also overall in line with those reported for other compounds, including IL-17i.12 13 18 31 However, few placebo-controlled studies in bDMARD-IR AS patients are available. In addition, subgroup analyses showed consistent improvements in ASAS40 responses with upadacitinib treatment irrespective of CRP elevation at baseline and the number or type of previous bDMARDs used, although the number of patients exposed to IL-17i and two bDMARDs were small.

Overall, upadacitinib was well tolerated. As the study was conducted during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the observed events reflect the prevalence of COVID-19 and the associated hospitalisation rate at the time the study was conducted.32 In this study, all COVID-19 events resolved and were considered to have no reasonable possibility of being related to upadacitinib as assessed by the investigators. Only one patient who experienced a COVID-19-related AE was vaccinated. Longer-term data from this trial will help to inform about the impact of upadacitinib treatment and vaccination status in the development of COVID-19-related AEs in the AS patient population. Available data from other inflammatory arthritic conditions such as RA and PsA suggest that the rates of COVID-19 infection were lower or similar in patients treated with upadacitinib than adalimumab.33 Notably, JAK inhibition has been recognised as an option to treat severe COVID-19.34 The safety profile of upadacitinib in this bDMARD-IR AS population was generally consistent with that observed in SELECT-AXIS 121–23 and the RA35 and PsA36 37 programmes. Herpes zoster occurrence has been reported with JAKi therapy with a particularly increased rate in patients of Asian descent,35 38 39 which is aligned with the findings of this study. No deaths, opportunistic infections, malignancy and adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular or venous thromboembolic events were reported with upadacitinib.

A few limitations of our study should be acknowledged. In the absence of an active comparator, data comparison with a similar AS bDMARD-IR population treated with another therapy should be made in the appropriate context. The decision to define a patient as having an IR due to a lack of efficacy or intolerance to a bDMARD was based solely on the discretion of the study investigators, which is also in line with the approach used in other studies.12 13 A lack of an established definition of an IR to therapy may explain potential patient selection variability, which may have influenced the magnitude of treatment responses.14 Rates of extra-musculoskeletal manifestations including uveitis or IBD in this study and SELECT-AXIS 1 were low overall,22 and upadacitinib has been shown to be effective in phase 3 IBD trials.40–43 However, few patients had a history of uveitis and IBD at baseline, and case report forms documenting efficacy in uveitis and IBD were not used.44 Therefore, additional data are needed to derive definitive conclusions about the efficacy of upadacitinib treatment on uveitis. Lastly, the ongoing long-term extension study will provide data on when upadacitinib treatment reaches a therapeutic plateau in this treatment-refractory AS population and whether there is similar efficacy in terms of maintenance of response through 2 years as observed in SELECT-AXIS 1.23

In summary, upadacitinib 15 mg once daily significantly improved the signs and symptoms of active AS in bDMARD-IR patients after 14 weeks of treatment compared with placebo. Treatment with upadacitinib was generally safe and well tolerated. No new safety risks were identified compared with the known safety profile of upadacitinib. These findings show that upadacitinib, which offers the convenience of an oral therapy,45 may be an effective treatment option for patients with active AS, including those with treatment-refractory AS who have shown an IR based on lack of efficacy or intolerance to bDMARD therapy.

Acknowledgments

AbbVie and the authors thank the patients, study sites, and investigators who participated in this clinical trial. Medical writing support was provided by Julia Zolotarjova, MSc, MWC, of AbbVie. Editorial support was provided by Angela T. Hadsell of AbbVie.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Contributors: The corresponding author is guarantor and accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish. DvdH and JS contributed to the study design. XB contributed to data generation. AD contributed to the study design and was an investigator in the study. RDI and XZ were investigators in the study. ALP and I-HS conceived the idea of study concept and contributed to the study design. PW was involved in the execution of the study. YS and XB conducted the statistical analyses. All authors analysed and interpreted the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors and Julia Zolotarjova wrote the article. All authors critically revised the article for important intellectual content.

Funding: AbbVie Inc. (North Chicago, IL, USA) funded this study and participated in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: DvdH has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Bayer, BMS, Cyxone, Eisai, Galapagos, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; is the director of Imaging Rheumatology BV; is an Associate Editor of the Annals of Rheumatic Diseases; is an editorial board member of the Journal of Rheumatology; and is an advisor for the Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society. XB has received grant/research support from AbbVie and Novartis; consulting fees from AbbVie, BMS, Chugai, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; speakers’ bureau fees from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Chugai, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and is an editorial board member of the Annals of Rheumatic Diseases. JS has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Merck, and UCB; has been a consultant for AbbVie, Merck, Novartis, and UCB; and has served on the speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Merck, and Novartis. AD has received grant/research support from AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, GSK, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and honoraria or consultation fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Aurinia, BMS, Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. RDI has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, and Novartis; and has been a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sandoz. HK has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Asahi-Kasei, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, Eisai, and Mitsubishi-Tanabe; consulting fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, and UCB; and received speakers’ bureau fees from AbbVie, Asahi-Kasei, BMS, Chugai, Eisai, Janssen, Lilly, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Novartis, and Pfizer. XZ has none declared. YS, XB, PW and I-HS are employees of AbbVie and may own stock or options. ALP is a former employee of AbbVie and may own stock or options.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent, scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the USA and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted according to the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines, local regulations and guidelines governing clinical study conduct, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol and consent forms were approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site. All patients provided written informed consent.

References

- 1. Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet 2017;390:73–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:777–83. 10.1136/ard.2009.108233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boel A, Molto A, van der Heijde D, et al. Do patients with axial spondyloarthritis with radiographic sacroiliitis fulfil both the modified New York criteria and the ASAS axial spondyloarthritis criteria? Results from eight cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1545–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondylarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:905–10. 10.1002/acr.21621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stolwijk C, Boonen A, van Tubergen A, et al. Epidemiology of spondyloarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2012;38:441–76. 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Navarro-Compán V, Sepriano A, El-Zorkany B, et al. Axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1511–21. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Winter JJ, van Mens LJ, van der Heijde D, et al. Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:196. 10.1186/s13075-016-1093-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, et al. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:65–73. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nikiphorou E, Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, et al. Association of comorbidities in spondyloarthritis with poor function, work disability, and quality of life: results from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society Comorbidities in Spondyloarthritis study. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:1257–62. 10.1002/acr.23468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:978–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1599–613. 10.1002/art.41042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sieper J, Deodhar A, Marzo-Ortega H, et al. Secukinumab efficacy in anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced subjects with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from the MEASURE 2 Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:571–92. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Pacheco-Tena C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in the treatment of radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: sixteen-week results from a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with prior inadequate response to or intolerance of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:599–611. 10.1002/art.40753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rudwaleit M, Van den Bosch F, Kron M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis and history of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R117. 10.1186/ar3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ørnbjerg LM, Brahe CH, Askling J, et al. Treatment response and drug retention rates in 24 195 biologic-naïve patients with axial spondyloarthritis initiating TNFi treatment: routine care data from 12 registries in the EuroSpA collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1536–44. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Gensler LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (TORTUGA): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;392:2378–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1340–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deodhar A, Sliwinska-Stanczyk P, Xu H, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1004–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Veale DJ, McGonagle D, McInnes IB, et al. The rationale for Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology 2019;58:197–205. 10.1093/rheumatology/key070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McInnes IB, Szekanecz Z, McGonagle D, et al. A review of JAK–STAT signalling in the pathogenesis of spondyloarthritis and the role of JAK inhibition. Rheumatology 2022;61:1783–94. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van der Heijde D, Song I-H, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:2108–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32534-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and an inadequate response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug therapy: one-year results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study and open-label extension. Arthritis Rheumatol 2022;74:70–80. 10.1002/art.41911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Maksymowych W. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: 2-year results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with open-label extension [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ismail M, Nader A, Winzenborg I. Exposure-response analyses for upadacitinib efficacy and safety in ankylosing spondylitis – analyses of the SELECT-AXIS I study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68 Suppl 2:ii1–44. 10.1136/ard.2008.104018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Machado PM, Landewé R, Heijde Dvander, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): 2018 update of the nomenclature for disease activity states. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1539–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Salonen D, et al. Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging index for assessment of spinal inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:502–9. 10.1002/art.21337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Salonen D, et al. Spondyloarthritis research Consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging index for assessment of sacroiliac joint inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:703–9. 10.1002/art.21445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolff D, Nee S, Hickey NS, et al. Risk factors for Covid-19 severity and fatality: a structured literature review. Infection 2021;49:15–28. 10.1007/s15010-020-01509-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van der Heijde D, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Dougados M, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A antagonist in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis or radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (COAST-V): 16 week results of a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, active-controlled and placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:2441–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31946-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reese H, Iuliano AD, Patel NN, et al. Estimated incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) illness and hospitalization-United States, February-September 2020. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72:e1010–7. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burmester G, Cohen S, Winthrop K. Long-term safety profile of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Solimani F, Meier K, Ghoreschi K. Janus kinase signaling as risk factor and therapeutic target for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Immunol 2021;51:1071–5. 10.1002/eji.202149173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen SB, van Vollenhoven RF, Winthrop KL, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analysis from the SELECT phase III clinical programme. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;80:304–11. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McInnes IB, Kato K, Magrey M, et al. Upadacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to non-biological therapy: 56-week data from the phase 3 SELECT-PsA 1 study. RMD Open 2021;7:e001838. 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mease PJ, Lertratanakul A, Papp KA, et al. Upadacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis and inadequate response to biologics: 56-week data from the randomized controlled phase 3 SELECT-PsA 2 study. Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:903–19. 10.1007/s40744-021-00305-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamaoka K, Tanaka Y, Kameda H, et al. The safety profile of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Japan. Drug Saf 2021;44:711–22. 10.1007/s40264-021-01067-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burmester GR, Nash P, Sands BE, et al. Adverse events of special interest in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis and psoriasis with 37 066 patient-years of tofacitinib exposure. RMD Open 2021;7:e001595. 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Loftus EV, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in a randomized trial of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2020;158:2123–38. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, et al. Efficacy of upadacitinib in a randomized trial of patients with active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;158:2139–49. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vermeire S, Danese S, Zhou W, et al. OP23 Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib as induction therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from phase 3 U-ACCOMPLISH study. J Crohns Colitis 2021;15:S021–2. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab075.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Panaccione R, Hebuterne X, Lindsay J. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib maintenance therapy in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from a randomized phase 3 study [abstract]. United European Gastroenterol J 2021;9. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dougados M, Braun J, Vargas RB, et al. ASAS recommendations for variables to be collected in clinical trials/epidemiological studies of spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1103–4. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Joo W, Almario CV, Ishimori M, et al. Examining treatment decision-making among patients with axial spondyloarthritis: insights from a conjoint analysis survey. ACR Open Rheumatol 2020;2:391–400. 10.1002/acr2.11151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rubin DB, Schenker N. Interval estimation from multiply-imputed data: a case study using census agriculture industry codes. J Am Stat Assoc 1987;3:375–87. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ard-2022-222608supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent, scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the USA and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.