Abstract

Objectives

To characterise infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in ORAL Surveillance.

Methods

In this open-label, randomised controlled trial, patients with RA aged≥50 years with ≥1 additional cardiovascular risk factor received tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg two times per day or a tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi). Incidence rates (IRs; patients with first events/100 patient-years) and hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated for infections, overall and by age (50–<65 years; ≥65 years). Probabilities of infections were obtained (Kaplan-Meier estimates). Cox modelling identified infection risk factors.

Results

IRs/HRs for all infections, serious infection events (SIEs) and non-serious infections (NSIs) were higher with tofacitinib (10>5 mg two times per day) versus TNFi. For SIEs, HR (95% CI) for tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi, respectively, were 1.17 (0.92 to 1.50) and 1.48 (1.17 to 1.87). Increased IRs/HRs for all infections and SIEs with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi were more pronounced in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years. SIE probability increased from month 18 and before month 6 with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi, respectively. NSI probability increased before month 6 with both tofacitinib doses versus TNFi. Across treatments, the most predictive risk factors for SIEs were increasing age, baseline opioid use, history of chronic lung disease and time-dependent oral corticosteroid use, and, for NSIs, female sex, history of chronic lung disease/infections, past smoking and time-dependent Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, C-reactive protein.

Conclusions

Infections were higher with tofacitinib versus TNFi. Findings may inform future treatment decisions.

Trial registration number

Keywords: antirheumatic agents; arthritis, rheumatoid; therapeutics; tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have an increased susceptibility to infections due to multiple factors, including age, disease activity, comorbidities and RA treatments.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In patients with RA aged≥50 years and with ≥1 additional cardiovascular risk factor, dose-dependent increases in the incidence and risk of all infections, serious infection events (SIEs) and non-serious infections (NSIs) were observed with tofacitinib (5 mg two times per day (recommended dosage for RA) and 10 mg two times per day) versus tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi).

Across treatment groups, the incidence of all infections and SIEs were increased in patients aged≥65 versus 50–<65 years, with increased risks more pronounced with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi in older patients.

Across treatment groups, the most predictive risk factors for SIEs were increasing age, baseline opioid use, history of chronic lung disease and time-dependent oral corticosteroid use; while those for NSIs were female sex, history of chronic lung disease/infections, past smoking and time-dependent higher Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, C-reactive protein score.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

These findings from ORAL Surveillance may inform treatment decisions for patients with RA; the higher risk of infections with tofacitinib versus TNFi, and risk factors identified for infections, should be considered as part of the shared decision-making between physicians and patients.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory autoimmune disorder.1 Compared with the general population, patients with RA are at a greater risk of infections, including serious infections requiring hospitalisation.2 3 In patients with RA, infections contribute to morbidity and mortality4 5 and may cause treatment discontinuation.6

The increased susceptibility to infections in patients with RA has been attributed to disease pathophysiology, comorbidities, lifestyle factors and use of immunomodulatory drugs.3 Analyses of real-world and clinical trial data from patients with RA have shown that the risk of serious and non-serious infections (NSIs) is increased in those receiving biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) versus conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs),7 8 and the risk of infections varies across treatments. For example, the tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi), etanercept, has been associated with reduced risk of infections versus other TNFi agents9–11 and the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, tofacitinib.12

ORAL Surveillance was a postauthorisation study that assessed the safety of tofacitinib versus TNFi in patients with RA aged≥50 years with ≥1 additional cardiovascular (CV) risk factor.13 An ad hoc safety analysis of ORAL Surveillance reported the incidence of non-fatal and fatal serious infection events (SIEs) to be greater with tofacitinib versus TNFi.14 Risk of SIEs (non-fatal/fatal) with tofacitinib was further increased in patients aged>65 years versus younger patients14; therefore, the European Medicines Agency recommended that patients aged>65 years should be treated with tofacitinib only when there is no suitable alternative treatment.15 Along with increasing age, a safety analysis of randomised controlled trials/long-term extension (LTE) studies (excluding ORAL Surveillance) identified tofacitinib dose, male sex, geographical region (Asia and Australia/New Zealand/rest of the world (ROW) versus the USA/Canada), increasing Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index Score, postbaseline lymphopenia, corticosteroid use, increasing body mass index (BMI) and history of diabetes and chronic lung disease as significant risk factors for SIEs in tofacitinib-treated patients.16

Using the final dataset from ORAL Surveillance, we sought to compare infections in patients with RA receiving tofacitinib versus TNFi, and to identify risk factors for infections in these patients.

Methods

Study design and patients

ORAL Surveillance was a phase IIIb/IV randomised, open-label, safety endpoint study conducted from March 2014 to July 2020 in patients with active RA despite methotrexate treatment who were aged≥50 years with ≥1 additional CV risk factor.13

Patients with infections requiring treatment≤2 weeks prior to study start or infections requiring hospitalisation or parenteral antimicrobial therapy≤6 months prior to study start were excluded. Patients had to screen negative for active tuberculosis (TB) or inadequately treated TB (active or latent) at study entry and annually for the full study duration. Patients newly testing positive for latent TB had to receive isoniazid or other TB prophylaxis to continue in the study. Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are published elsewhere.13

Patients were randomised 1:1:1 to receive oral tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg two times per day, or subcutaneous TNFi (adalimumab 40 mg once every 2 weeks (North America: the United States, Puerto Rico and Canada) or etanercept 50 mg once weekly (ROW)). Patients continued their prestudy stable dose of methotrexate unless modification was clinically indicated.

In February 2019, following a study amendment, the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day dose was reduced to 5 mg two times per day after the Data Safety Monitory Board noted an increased frequency of pulmonary embolism in patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi and an increase in overall mortality with tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day and TNFi.

If a patient experienced an SIE, they may have had their study drug temporarily discontinued until they recovered, but they were not excluded from the study.

ORAL Surveillance was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Council on Harmonisation, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and/or Independent Ethics Committee at each centre. Patients provided written informed consent.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Outcomes

Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) assessed in this analysis included: all infections, SIEs (non-fatal/fatal), NSIs, herpes zoster (HZ) and adjudicated opportunistic infections (including HZ and TB). These events are defined in online supplemental material.

ard-2022-222405supp001.pdf (180.1KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Safety outcomes were analysed using the safety analysis set, which included all randomised patients receiving ≥1 dose of study drug. For patients randomised to tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day who had their dose reduced to 5 mg two times per day in February 2019, the data collected after the dose switch were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group.

Infection events were counted within the predefined risk period, based on the 28-day on-treatment time, defined as time from the first study dose to the last study dose +28 days or to the last contact date, whichever was earliest. The last contact date was defined as the maximum of AE start date, AE stop date, last visit date, withdrawal date or telephone contact date; if a patient died, the last contact date was the death date. Patients without events were censored at the end of the risk period. For patients with multiple SIEs, NSIs and HZ, these were reported as separate events if the event start dates were different.

Crude incidence rates (IRs; for all infections, SIEs, NSIs and HZ) were expressed as the number of patients with first events per 100 patient-years, along with two-sided 95% CIs derived by exact Poisson method.17 HR (for all infections, SIEs, NSIs and HZ) and 95% CIs for pairwise treatment comparisons (tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi; tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day) were estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression models.18

For SIEs, the number needed to harm (NNH; number of patient-years of tofacitinib exposure needed to have one additional AE relative to TNFi) was calculated post hoc for tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi. The NNH for patients exposed for 5 years was calculated by dividing the number of patient-years needed to harm by 5.

The cumulative probabilities of patients experiencing a first event (SIE, NSI and HZ) at specific time intervals after initiation of each treatment were measured post hoc using Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survivor function.

Potential baseline and time-dependent risk factors (online supplemental table 1) for first SIEs, NSIs and all HZ (non-serious and serious) were evaluated post hoc, overall and for each individual treatment group; a model selection process was conducted using Cox proportional hazards (simple and multivariable) regression models (additional details are in online supplemental material).

Across all analyses, no adjustments for multiple comparisons were applied.

Results

Patients

Overall, 4362 patients were randomised and treated (tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day: N=1455; tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day: N=1456; TNFi: N=1451); median follow-up was 4.0 years. Total exposure was 5073.5, 4773.4 and 4940.7 patient-years for tofacitinib 5 or 10 mg two times per day, or TNFi, respectively.13 For the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group, approximately 79% of exposure occurred prior to the study amendment (ie, before patients randomised to tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day had their dose reduced to 5 mg two times per day); approximately 21% of exposure occurred after patients had switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day. Table 1 shows selected patient demographics/baseline disease characteristics; full details are published elsewhere.13

Table 1.

Selected demographics and baseline disease characteristics in ORAL Surveillance

| Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=1455) | Tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day (N=1456) | TNFi (N=1451) |

|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 60.8 (6.8) | 61.4 (7.1) | 61.3 (7.5) |

| ≥65 years, n (%) | 413 (28.4) | 478 (32.8) | 462 (31.8) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 286 (19.7) | 332 (22.8) | 334 (23.0) |

| RA disease duration (years), mean (SD) | 10.4 (8.8) | 10.2 (9.0) | 10.6 (9.3) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Current smoker | 411 (28.2) | 402 (27.6) | 353 (24.3) |

| Past smoker | 309 (21.2) | 302 (20.7) | 326 (22.5) |

| Never smoked | 735 (50.5) | 752 (51.6) | 772 (53.2) |

| Geographical region, n (%)* | |||

| North America | 402 (27.6) | 409 (28.1) | 432 (29.8) |

| ROW | 1053 (72.4) | 1047 (71.9) | 1019 (70.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) (number of patients with missing values) | 29.7 (6.5) (7) | 29.7 (6.3) (3) | 29.8 (6.6)(7) |

| ≥30 kg/m2, n (%) | 606 (41.6) | 594 (40.8) | 617 (42.5) |

| ≥35 kg/m2, n (%) | 256 (17.6) | 261 (17.9) | 267 (18.4) |

| Concomitant medication use at baseline (day 1) | |||

| Opioids, n (%) | 293 (20.1) | 283 (19.4) | 288 (19.8) |

| Oral corticosteroids, n (%) | 776 (53.3) | 773 (53.1) | 774 (53.3) |

| Oral corticosteroid dose (mg/day), mean (range)† | 6.0‡ (0.7–20.0) | 6.1§ (0.6–20.0) | 6.1¶ (0.3–20.0) |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 243 (16.7) | 261 (17.9) | 255 (17.6) |

| Chronic lung disease (COPD or ILD) | 178 (12.2) | 173 (11.9) | 172 (11.9) |

| Extra-articular disease | 532 (36.6) | 521 (35.8) | 552 (38.0) |

| Nodules | 301 (20.7) | 268 (18.4) | 287 (19.8) |

| Coronary artery disease | 161 (11.1) | 172 (11.8) | 164 (11.3) |

| Heart failure | 18 (1.2) | 23 (1.6) | 18 (1.2) |

| Infection | 574 (39.5) | 549 (37.7) | 556 (38.3) |

| Positive for anticitrullinated protein antibodies, n (%) | 1093 (75.1) | 1129 (77.5) | 1119 (77.1) |

| HAQ-DI, mean (SD) (number of patients with missing values) | 1.6 (0.6) (11) | 1.6 (0.6) (18) | 1.6 (0.6) (25) |

| DAS28-4(CRP), mean (SD) (number of patients with missing values) | 5.8 (0.9) (11) | 5.8 (0.9) (17) | 5.8 (0.9) (26) |

For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group.

*In North America (the USA, Puerto Rico and Canada), patients randomised to TNFi received adalimumab 40 mg once every 2 weeks; in the ROW, patients randomised to TNFi received etanercept 50 mg once weekly.

†In patients taking oral corticosteroids at baseline with known dosing information.

‡n=769.

§n=771.

¶n=773.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DAS28-4(CRP), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, C-reactive protein; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; ILD, interstitial lung disease; n, number of patients meeting baseline criteria; N, number of evaluable patients; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; ROW, rest of the world; SD, standard deviation; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

Across treatments, 4.7%–5.2% of patients were reported to have received HZ vaccination (Zostavax or Shingrix) prior to study start, and 0.3%–0.8% of patients received HZ vaccination on/after study day 1. At screening, 11.5%–12.3% of patients had latent TB with a positive QuantiFERON Gold or tuberculin skin test and negative chest radiograph, and received isoniazid or other TB prophylaxis prior to the first dose of study drug. Overall, 16.8%–20.2% of patients received isoniazid or other TB prophylaxis on/after the first dose of study drug.

Incidence and risk of infections in ORAL Surveillance

Incidence and risk of all infections

Across treatments, the most frequent treatment-emergent AEs by Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities’ System Organ Class were infections and infestations.13 The most frequently reported infections were upper respiratory tract infections, bronchitis and urinary tract infections (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of infection AEs in ORAL Surveillance

| Patients with events, n (%) | Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=1455) | Tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day (N=1456) | TNFi (N=1451) |

| Infections and Infestations (MedDRA System Organ Class)* | 1036 (71.2) | 1055 (72.5) | 930 (64.1) |

| Most frequently reported, by MedDRA Preferred Term (≥3% of patients with events in any treatment group)* | |||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 308 (21.2) | 312 (21.4) | 255 (17.6) |

| Bronchitis | 222 (15.3) | 237 (16.3) | 163 (11.2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 186 (12.8) | 221 (15.2) | 184 (12.7) |

| HZ (non-serious/serious)† | 176 (12.1) | 167 (11.5) | 55 (3.8) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 164 (11.3) | 165 (11.3) | 158 (10.9) |

| Pneumonia | 95 (6.5) | 101 (6.9) | 78 (5.4) |

| Sinusitis | 92 (6.3) | 79 (5.4) | 91 (6.3) |

| Pharyngitis | 86 (5.9) | 79 (5.4) | 75 (5.2) |

| Influenza | 90 (6.2) | 91 (6.3) | 71 (4.9) |

| Latent TB | 87 (6.0) | 67 (4.6) | 91 (6.3) |

| Gastroenteritis | 64 (4.4) | 79 (5.4) | 53 (3.7) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 43 (3.0) | 43 (3.0) | 31 (2.1) |

| Cellulitis | 36 (2.5) | 32 (2.2) | 50 (3.4) |

| SIEs | 141 (9.7) | 169 (11.6) | 119 (8.2) |

| Non-fatal | 135 (9.3) | 156 (10.7) | 115 (7.9) |

| Fatal | 6 (0.4) | 13 (0.9) | 4 (0.3) |

| Patients with 1 SIE | 110 (7.6) | 140 (9.6) | 95 (6.6) |

| Patients with 2 SIEs‡ | 22 (1.5) | 23 (1.6) | 18 (1.2) |

| Patients with 3 SIEs‡ | 7 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.3) |

| Patients with ≥4 SIEs‡ | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| NSIs | 983 (67.6) | 1003 (68.9) | 882 (60.8) |

| Patients with 1 NSI event | 307 (21.1) | 326 (22.4) | 334 (23.0) |

| Patients with 2 NSI events‡ | 226 (15.5) | 228 (15.7) | 200 (13.8) |

| Patients with 3 NSI events‡ | 160 (11.0) | 135 (9.3) | 117 (8.1) |

| Patients with ≥4 NSI events‡ | 290 (19.9) | 314 (21.6) | 231 (15.9) |

| NSIs excluding all HZ | 954 (65.6) | 968 (66.5) | 870 (60.0) |

| All HZ (non-serious/serious)§ | 180 (12.4) | 178 (12.2) | 58 (4.0) |

| Seriousness | |||

| Non-serious¶ | 170 (94.4) | 161 (90.4) | 56 (96.6) |

| Serious¶ | 10 (5.6) | 17 (9.6) | 2 (3.4) |

| Severity | |||

| Mild¶ | 61 (33.9) | 49 (27.5) | 16 (27.6) |

| Moderate¶ | 110 (61.1) | 116 (65.2) | 40 (69.0) |

| Severe¶ | 9 (5.0) | 13 (7.3) | 2 (3.4) |

| All HZ (non-serious/serious)§ | |||

| Patients with 1 HZ event | 138 (9.5) | 137 (9.4) | 46 (3.2) |

| Patients with 2 HZ events‡ | 33 (2.3) | 35 (2.4) | 11 (0.8) |

| Patients with 3 HZ events‡ | 9 (0.6) | 5 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Patients with ≥4 HZ events‡ | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Adjudicated multidermatomal HZ** | 29 (2.0) | 24 (1.7) | 12 (0.8) |

| Adjudicated special interest HZ†† | 17 (1.2) | 17 (1.2) | 4 (0.3) |

| Discontinuation from study drug due to HZ | 6 (0.4) | 12 (0.8) | 2 (0.1) |

| Adjudicated opportunistic infections* | 39 (2.7) | 44 (3.0) | 21 (1.5) |

| HZ adjudicated as an opportunistic infection*,‡‡ | 34 (2.3) | 32 (2.2) | 13 (0.9) |

| TB adjudicated as an opportunistic infection* | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) |

| Adjudicated opportunistic infections excluding HZ and TB | 4 (0.3) | 7 (0.5) | 3 (0.2) |

For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group.

*Reported elsewhere.13

†Includes the Preferred Term HZ from the clinical database recorded on the AE case report forms.

‡Events were counted as separate events if the event start dates were different.

§Includes HZ adjudicated as opportunistic infections and non-adjudicated HZ events, which included preferred terms of genital HZ, HZ, HZ cutaneous disseminated, HZ disseminated, HZ infection neurological, HZ meningitis, HZ meningoencephalitis, HZ necrotising retinopathy, HZ oticus, HZ pharyngitis, ophthalmic HZ, HZ ophthalmic and HZ multidermatomal, from the clinical database recorded on the AE case report forms.

¶Percentages calculated based on number of patients with HZ adjudicated as opportunistic infections and non-adjudicated HZ events from the clinical database.

**Cases of HZ involving non-adjacent dermatomes or >2 adjacent dermatomes.

††Cases of HZ involving two adjacent dermatomes.

‡‡Cases of multidermatomal HZ and disseminated HZ (diffuse rash (>6 dermatomes)), encephalitis, pneumonia and other organ involvement) were adjudicated as opportunistic infections.

AE, adverse event; HZ, herpes zoster; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; n, number of patients with events; N, number of evaluable patients; NSI, non-serious infection; SIE, serious infection event; TB, tuberculosis; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

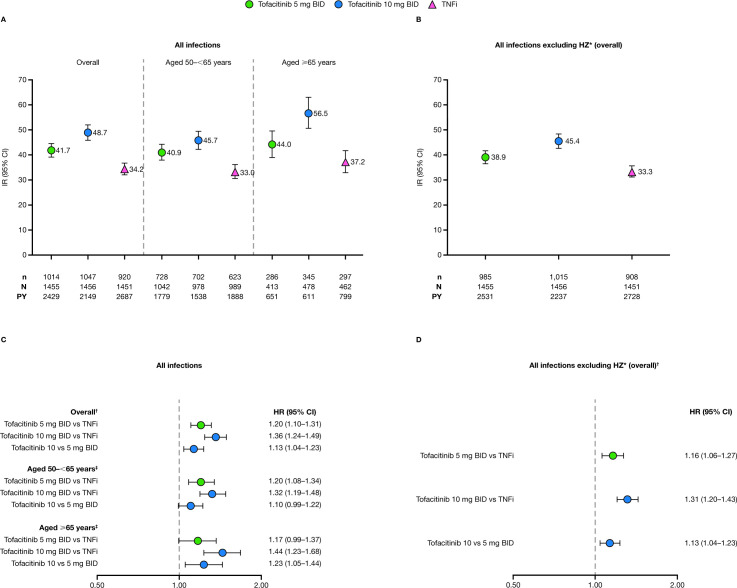

For all infections, and infections excluding HZ, IRs were higher and risk was increased for both tofacitinib doses versus TNFi and for tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day (figure 1). Across treatments, IRs for all infections were greater in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years (figure 1A). In both age groups, risk for all infections increased with tofacitinib (10>5 mg two times per day) versus TNFi (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

IRs (patients with first events/100 PY; 95% CIs) for (A) all infections, overall and stratified by age, and (B) all infections excluding HZ; and HRs (95% CIs) for (C) all infections, overall and stratified by age, and (D) all infections excluding HZ, in ORAL Surveillance. HRs are shown on a logarithmic scale. For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group. *Excludes HZ adjudicated as opportunistic infections and non-adjudicated HZ events from the clinical database. †HRs (95% CIs) based on a simple Cox proportional hazard model for pairwise treatment comparisons, with treatment as covariate. ‡HRs (95% CIs) based on a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model for pairwise treatment comparisons with treatment, sex, region and smoking as covariates. BID, two times per day; HR, hazard ratio; HZ, herpes zoster; IR, incidence rate; N, number of evaluable patients; n, number of patients with events; PY, patient-years; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

HRs for the combined tofacitinib doses versus TNFi for all infections and all infections excluding HZ (as well as SIEs, NSIs, NSIs excluding HZ and all HZ) are shown in online supplemental table 2).

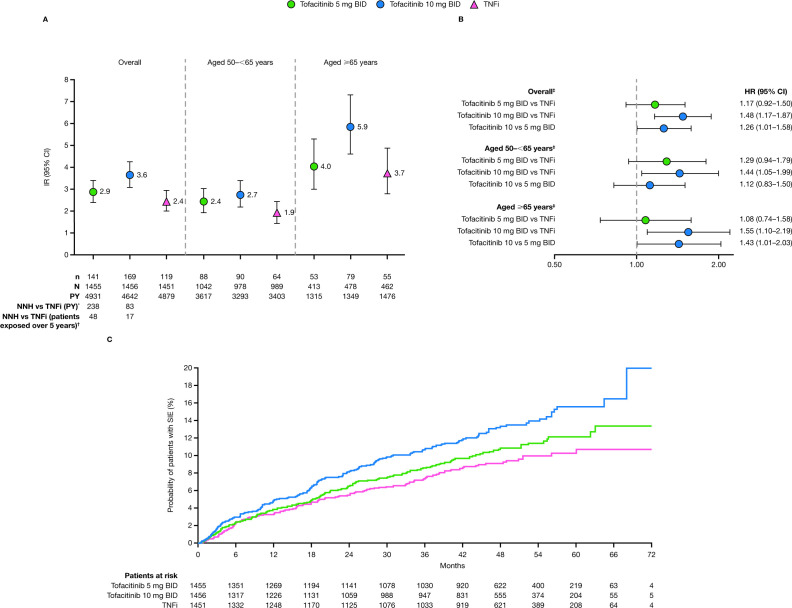

Incidence and risk of SIEs

Across treatments, IRs of SIEs (non-fatal/fatal) were greater in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years (figure 2A). Overall, IRs of SIEs were higher with tofacitinib (10>5 mg two times per day) versus TNFi. NNH was 238 and 83 patient-years, respectively, for tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day (figure 2A), corresponding to 48 and 17 patients who would need to be treated with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day, respectively, versus TNFi, over 5 years to have one additional event. Similar trends for IRs were observed across age groups. Risk increased with both tofacitinib doses versus TNFi and tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day, although 95% CIs for HRs included 1 for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus TNFi, overall and across age groups, and for tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day for patients aged≥50–<65 years (figure 2B). The increased risk for SIEs with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi (and tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day) was more pronounced in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years (figure 2B). Cumulative probability of a first SIE with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi increased from month 18 and before month 6, respectively (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) IRs (patients with first events/100 PY; 95% CIs) and (B) HRs (95% CIs) for SIEs, overall and stratified by age; and (C) cumulative probabilities of experiencing a first SIE (Kaplan-Meier method), in ORAL Surveillance. HRs are shown on a logarithmic scale. For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group. IRs and HRs for SIEs overall have been reported previously.13 *Number of PY of exposure to tofacitinib required to have one additional event, relative to a TNFi †Number of patients who would need to be treated over 5 years with tofacitinib rather than a TNFi to result in one additional event. ‡HRs (95% CIs) based on a simple Cox proportional hazard model for pairwise treatment comparisons, with treatment as covariate. BID, two times per day; HR, hazard ratio; IR, incidence rate; N, number of evaluable patients; n, number of patients with events; PY, patient-years; SIE, serious infection event; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

A total of 31 (2.1%) patients in the tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day group, 29 (2.0%) patients in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group and 24 (1.7%) patients in the TNFi group experienced multiple SIEs (table 2).

Risk of fatal SIEs was greater with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi (HR (95% CI), 3.34 (1.09 to 10.25)); HRs were 1.47 (0.41 to 5.21) for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus TNFi and 2.27 (0.86 to 5.98) for tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day.

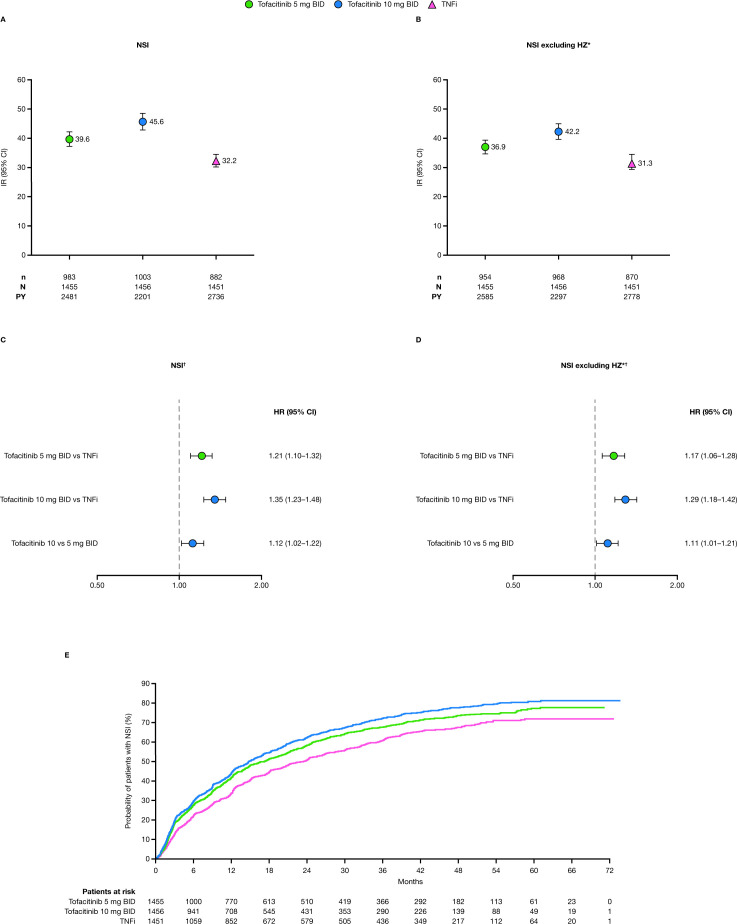

Incidence and risk of NSIs

For NSIs, and NSIs excluding HZ, IRs were higher and risk was increased with tofacitinib (10>5 mg two times per day) versus TNFi and tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day (figure 3). The cumulative probability of a first NSI with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi increased before month 6 (figure 3E).

Figure 3.

IRs (patients with first events/100 PY; 95% CIs) for (A) NSIs and (B) NSIs excluding HZ; HRs (95% CIs) for (C) NSIs and (D) NSIs excluding HZ; and (E) cumulative probabilities of experiencing a first NSI (Kaplan-Meier method), in ORAL Surveillance. HRs are shown on a logarithmic scale. For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group. *Excludes HZ adjudicated as opportunistic infections and non-adjudicated HZ events from the clinical database. †HRs (95% CIs) based on a simple Cox proportional hazard model for pairwise treatment comparisons, with treatment as covariate. BID, two times per day; HR, hazard ratio; HZ, herpes zoster; IR, incidence rate; N, number of evaluable patients; n, number of patients with events; NSI, non-serious infection; PY, patient-years; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

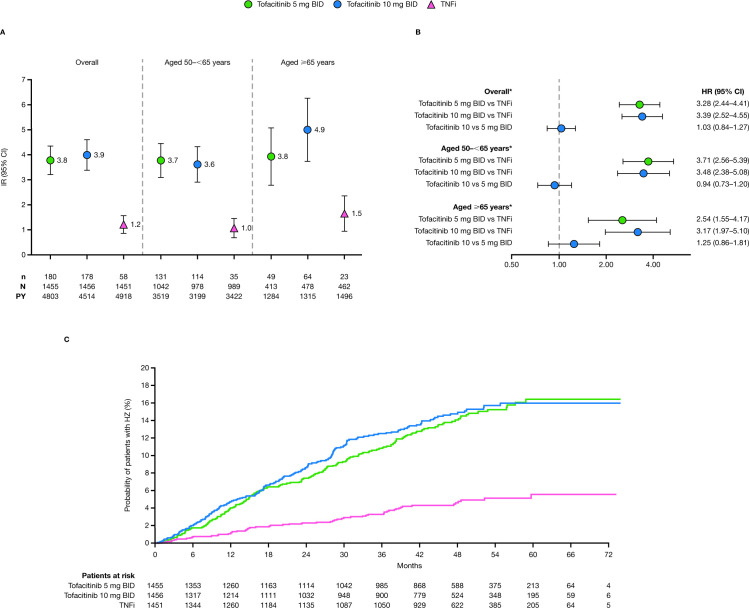

Incidence and risk of HZ

IRs of all HZ (non-serious/serious) were greater in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years (all treatments; figure 4A). IRs and risk for all HZ were greater with both doses of tofacitinib versus TNFi overall and across age groups (figure 4 A, B). The cumulative probability of a first HZ event with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi increased before month 6 (figure 4C).

Figure 4.

(A) IRs (patients with first events/100 PY; 95% CIs) and (B) HRs (95% CIs) for all HZ (non-serious/serious), overall and stratified by age; and (C) cumulative probabilities of experiencing a first HZ (non-serious/serious) event (Kaplan-Meier method), in ORAL Surveillance. HRs are shown on a logarithmic scale. For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group. All HZ events (non-serious/serious) include HZ adjudicated as opportunistic infections and non-adjudicated HZ events from the clinical database. *HRs based on a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model for pairwise treatment comparisons with treatment, age, region, smoking and baseline corticosteroid use as covariates. BID, two times per day; HR, hazard ratio; HZ, herpes zoster; IR, incidence rate; N, number of evaluable patients; n, number of patients with events; PY, patient-years; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

IRs (95% CIs) of adjudicated multidermatomal HZ were higher for tofacitinib 5 (0.6 (0.4 to 0.8)) and 10 mg two times per day (0.5 (0.3 to 0.7)) versus TNFi (0.2 (0.1 to 0.4)). IRs of adjudicated special interest HZ were also higher for tofacitinib 5 (0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) and 10 mg two times per day (0.4 (0.2 to 0.6)) versus TNFi (0.1 (0.0 to 0.2)).

A total of 42 (2.9%), 41 (2.8%) and 12 (0.8%) patients in the tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day, tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day and TNFi groups, respectively, reported multiple HZ events (table 2).

Risk factors for infections in ORAL Surveillance

Baseline and time-dependent risk factors across all treatments

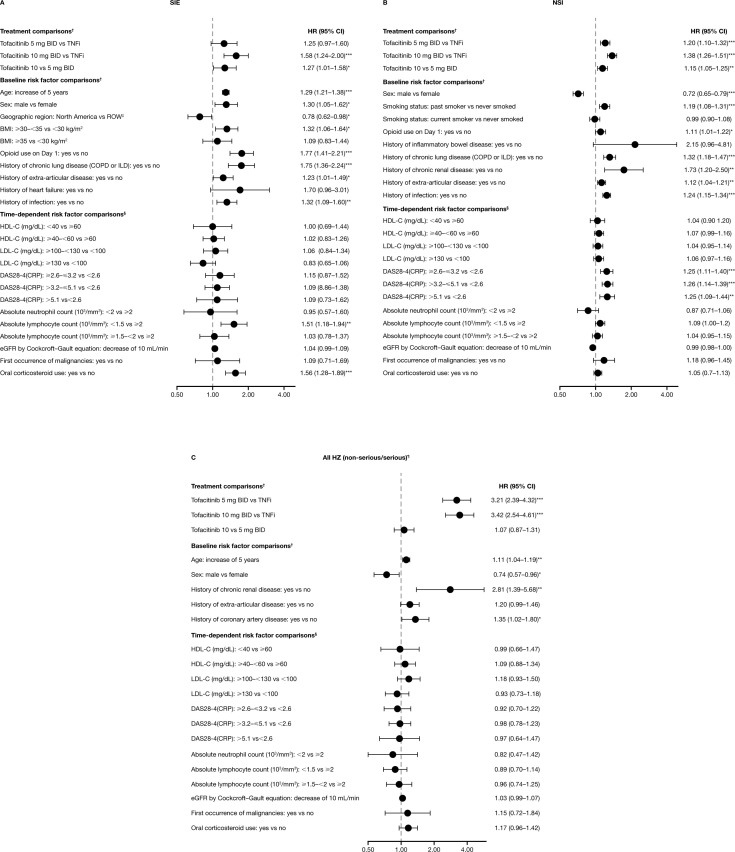

Risk factors for infections (p<0.10) identified via simple analyses across all treatments are shown in online supplemental table 3. Figure 5 shows risk factors for infections (p<0.10) identified via multivariable analyses across all treatments. The most predictive risk factors for SIEs were increasing age, opioid use, history of chronic lung disease at baseline and time-dependent oral corticosteroid use (p<0.001; figure 5A). Patients in North America had a 22% lower risk of SIEs versus patients in the ROW (p<0.05; figure 5A). The most predictive risk factors for NSIs were female sex, history of chronic lung disease/infections, past smoking at baseline and time-dependent higher Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, C-reactive protein score (p<0.001; figure 5B). The most predictive risk factors for all HZ (non-serious/serious) were increasing age, history of chronic renal disease, female sex and history of coronary artery disease at baseline (p<0.05; figure 5C).

Figure 5.

HRs (95% CIs) of potential baseline and time-dependent risk factors for (A) SIEs, (B) NSIs and (C) all HZ (non-serious/serious) in ORAL Surveillance (multivariable Cox analyses across treatments). For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. HRs are shown on a logarithmic scale. †HRs were based on a backward model selection algorithm on a multivariable Cox model, including effects of treatment group (tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day, 10 mg two times per day and TNFi) and a set of candidate baseline risk factors previously selected via a simple Cox model; risk factors with p<0.10 in the simple model (see online supplemental table 3) were entered into the multivariable model, and the risk factors with p<0.10 were retained in the multivariable model, with p<0.05 interpreted as predictive. ‡In North America (the USA, Puerto Rico and Canada), patients randomised to TNFi received adalimumab 40 mg once every 2 weeks; in the ROW, patients randomised to TNFi received etanercept 50 mg once weekly. §HRs were based on a multivariable Cox time-dependent model including the fixed effects of treatment group (tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day, tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day and TNFi), the final set of baseline covariates selected from the previous multivariable Cox model, using a backward selection algorithm and a time-dependent covariate (a separate model was generated for each individual time-dependent risk factor). ¶All HZ events (non-serious/serious) include HZ adjudicated as opportunistic infections and non-adjudicated HZ events from the clinical database. BID, two times per day; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DAS28-4(CRP), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HR, hazard ratio; HZ, herpes zoster; ILD, interstitial lung disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NSI, non-serious infection; ROW, rest of the world; SIE, serious infection event; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

Baseline risk factors for individual treatments

Baseline risk factors for infections (p<0.10) identified using simple analyses for individual treatments are shown in online supplemental table 4. Table 3 summarises baseline risk factors for infections (p<0.10) identified using multivariable analyses for individual treatments. The most predictive baseline risk factors for SIEs included: increasing age and history of chronic lung disease for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (p<0.001); increasing age (p<0.001) and opioid use (p<0.01) for tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day; and increasing age (p<0.001), opioid use and history of chronic lung disease for TNFi (p<0.01; table 2). The most predictive baseline risk factors for NSIs included: female sex, past smoking and history of chronic lung disease for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (p<0.001); female sex and history of infection for tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day; and history of infection (p<0.001) and female sex (p<0.01) for TNFi (table 3).

Table 3.

HRs (95% CIs) of potential baseline risk factors for SIEs and NSIs in ORAL Surveillance (multivariable Cox analyses performed for individual treatments)

| Baseline risk factor comparisons, HR (95% CI) |

Tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (N=1455) | Tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day (N=1456) | TNFi (N=1451) |

| SIEs | |||

| Age: increase of 5 years | 1.28 (1.14 to 1.44)*** | 1.32 (1.19 to 1.47)*** | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.41)*** |

| Positive for anticitrullinated protein antibodies: yes versus no | 2.08 (1.29 to 3.36)** | ||

| BMI: ≥30–<35 versus <30 kg/m2 | 1.72 (1.18 to 2.52)** | 1.37 (0.97 to 1.92) | |

| BMI: ≥35 versus <30 kg/m2 | 1.51 (0.96 to 2.38) | 0.77 (0.49 to 1.21) | |

| Opioid use on day 1: yes versus no | 1.63 (1.13 to 2.36)** | 1.67 (1.19 to 2.35)** | 1.91 (1.30 to 2.81)** |

| History of chronic lung disease (COPD or ILD): yes versus no | 2.13 (1.42 to 3.20)*** | 1.47 (0.98 to 2.23) | 1.85 (1.18 to 2.89)** |

| History of extra-articular disease: yes versus no | 1.36 (0.97 to 1.19) | ||

| History of heart failure: yes versus no | 2.17 (0.94 to 5.01)* | 2.82 (1.03 to 7.75)* | |

| History of infection: yes versus no | 1.34 (0.98 to 1.81) | 1.51 (1.05 to 2.17)* | |

| NSIs | |||

| Sex: male versus female | 0.73 (0.62 to 0.87)*** | 0.69 (0.59 to 0.81)*** | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.91)** |

| Race: non-white versus white | 1.19 (1.03 to 1.38)* | ||

| Smoking status: past smoker versus never smoked | 1.34 (1.14 to 1.58)*** | ||

| Smoking status: current smoker versus never smoked | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.18) | ||

| Opioid use day 1: yes versus no | 1.19 (1.02 to 1.39)* | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.43)* | |

| History of chronic lung disease (COPD or ILD): yes versus no | 1.38 (1.15 to 1.66)*** | 1.32 (1.09 to 1.59)** | 1.30 (1.06 to 1.59)* |

| History of chronic renal disease: yes versus no | 2.52 (1.39 to 4.59)** | 2.16 (1.19 to 3.93)* | |

| History of extra-articular disease: yes versus no | 1.21 (1.06 to 1.37)** | ||

| History of infection: yes versus no | 1.21 (1.06 to 1.37)** | 1.31 (1.15 to 1.49)*** | 1.27 (1.11 to 1.45)*** |

For patients randomised to the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group who had their dose of tofacitinib reduced to 5 mg two times per day, the data collected after patients were switched to tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day were counted in the tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group. HRs (95% CIs) were based on a backward selection algorithm used on a multivariable Cox model including candidate baseline risk factors previously selected via a simple Cox model; risk factors with p<0.10 in the simple model (see online supplemental table 4) were entered into the multivariable model, and the risk factors with p<0.10 were retained in the multivariable model, with p<0.05 interpreted as predictive. Blank cells indicate risk factors that were not included but retained in the final multivariable Cox model for that particular treatment (ie, risk factors with p≥0.10 in the final multivariable model).

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ILD, interstitial lung disease; NSI, non-serious infection; SIE, serious infection event; TNFi, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

The HRs for SIEs and NSIs comparing tofacitinib and TNFi were consistent when based on the simple Cox models (with treatment group as the only covariate; figures 2 and 3), multivariable Cox models via backward selection (figure 5) and multivariable Cox models with each of the time-dependent covariates included (data not shown).

Discussion

In ORAL Surveillance, there were dose-dependent increases in the IRs/HRs for all infections, SIEs and NSIs with tofacitinib versus TNFi. For SIEs, 95% CIs for HRs included 1 for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus TNFi, overall and across age groups. Kaplan-Meier plots suggested that patients were more likely to experience a first SIE with tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi from month 18 onwards and before month 6, respectively; and patients were more likely to experience a first NSI or HZ event with both tofacitinib doses versus TNFi before month 6. The increases in all infections and SIEs with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day vs TNFi (and tofacitinib 10 vs 5 mg two times per day) were more pronounced in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years. While the number of patients with repeated SIEs was generally balanced across treatment groups, a greater proportion of patients had 2, 3 and ≥4 NSIs with tofacitinib (both doses) versus TNFi. Across age groups, the incidence and risk of HZ was greater with both doses of tofacitinib versus TNFi. IRs of adjudicated opportunistic infections were <1 for all treatment groups and are published elsewhere.13

IRs of SIEs were higher in ORAL Surveillance relative to those previously reported in a pooled analysis of data from the Phase I–IIIb/IV and LTE tofacitinib clinical trials. In ORAL Surveillance, IRs (95% CI) were 2.9 (2.4 to 3.4) and 3.6 (3.1 to 4.2) for tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day, respectively, while in the wider tofacitinib clinical programme, IRs were 2.8 (2.5 to 3.2) and 2.3 (2.1 to 2.6) for average total daily doses of tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day, respectively.16 When inclusion criteria mimicking ORAL Surveillance (aged≥50 years with ≥1 additional CV risk factor (current smoker, hypertension, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol<40 mg/dL, diabetes mellitus, history of myocardial infarction or coronary heart disease at baseline)) were applied to the pooled Phase I–IIIb/IV and LTE data, IRs for SIEs increased to 3.7 (3.1 to 4.4) and 3.3 (2.8 to 3.8) for average tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg two times per day, respectively (data on file). Overall, this is in line with previous studies showing that traditional CV risk factors may contribute to an increased risk of SIEs in patients with RA.3 19

Increasing age is a known risk factor for infections in patients with RA and in the general population.20 21 In ORAL Surveillance, across all treatments, the incidence of infections, including SIEs, was generally greater in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years; this finding aligns with previous analyses of pooled phase III and LTE studies of tofacitinib-treated patients with RA22 and pooled phase II–IIIb/IV studies from the tofacitinib clinical programme.23 The SIE risk was similar between age groups for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day and adalimumab, but greater in older versus younger patients with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day.23 In ORAL Surveillance, an elevated risk of SIEs with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus the other treatment groups was present in both age groups, but was most pronounced among those aged≥65 years. These findings could guide shared decision-making in older patients with RA.

In ORAL Surveillance, incidence of SIEs was greater with both tofacitinib doses (10>5 mg two times per day) versus TNFi. Analyses of real-world data from a 5-year postauthorisation safety study using the US CorEvitas registry reported no significant differences in SIE risk with tofacitinib versus bDMARDs (including both TNFi and non-TNFi agents).24 Similarly, a real-world US claims database study observed no significant differences in risk of hospital admission for SIE between tofacitinib and a variety of bDMARDs, except for an increased risk with tofacitinib versus etanercept.12 It is likely that the real-world studies mainly included patients receiving tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (the approved dose for RA in the USA at the time), which may be why no significant differences in risk of SIEs were observed between tofacitinib and TNFi; this is similar to the results of ORAL Surveillance for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus TNFi. However, ORAL Surveillance differs from these real-world studies with regard to patient selection, study design and the RA treatments compared.

Previous studies have reported variation in the risk of SIEs between individual RA treatments.9–11 In the current multivariable analysis, patients in North America who received adalimumab had a lower risk of SIEs versus patients in the ROW who received etanercept. It is worth noting, however, that, in simple analyses, a higher crude risk of SIEs was observed for North America versus the ROW for the TNFi group but not for either tofacitinib dose (data not shown). Treatment comparisons across geographical regions are inherently biased; for example, IRs of comorbidities were generally higher in North America versus the ROW.13

Risk factors identified for SIEs in ORAL Surveillance were generally similar to those previously reported in an integrated safety analysis of patients with RA receiving tofacitinib16; common risk factors included tofacitinib dose, increasing age, male sex, geographical region (Asia and Australia/New Zealand/ROW vs the USA/Canada), corticosteroid use, increasing BMI, chronic lung disease and lymphopenia. The tofacitinib prescribing information requires the monitoring of lymphocyte counts at baseline and every 3 months.25 Previous analysis also identified history of diabetes as a predictive risk factor for SIEs with tofacitinib in patients with RA.16 In ORAL Surveillance, history of diabetes was identified as a predictive risk factor for SIEs in the simple but not the multivariable Cox regression analyses; it is possible that history of diabetes was strongly associated with other, more predictive baseline risk factors that were included within the final multivariable model. It should be noted that only increasing age and baseline opioid use were identified as predictive risk factors for SIEs for both tofacitinib doses when treatment groups were analysed individually. Baseline opioid use was also a risk factor for NSIs across all treatments combined and has previously been reported to increase the risk of infections in patients with RA.26 27 Other risk factors for NSIs, which have been previously reported in registry data analyses of patients with RA receiving bDMARDs, include female sex and comorbidities.8

In agreement with the current findings, real-world studies of patients with RA have consistently reported a greater risk of HZ (non-serious/serious) with JAK inhibitors versus bDMARDs.12 24 28 For example, real-world US registry and claims database studies of patients with RA reported that HZ risk was twofold higher with tofacitinib versus bDMARDs.12 24 Previously characterised risk factors for HZ with tofacitinib include increasing age, geographical region (Asia (particularly Japan and Korea) vs the USA/Canada), being a past smoker versus having never smoked, and corticosteroid use.16 It is noteworthy that geographical region, smoking status and corticosteroid use were not predictive risk factors for HZ in the current study.

A post hoc analysis of phase III studies of patients with RA evaluated the safety of tofacitinib administered as monotherapy or combined with csDMARDs, with or without corticosteroids at baseline.29 IRs of SIEs and HZ were the greatest in patients receiving tofacitinib combined with csDMARDs along with corticosteroid use at baseline. In ORAL Surveillance, oral corticosteroid use was a predictive risk factor for SIEs but not HZ. The impact of concomitant csDMARDs on IRs of infections was not evaluated in ORAL Surveillance, but it should be noted that all patients received methotrexate at the start of the trial.

A limitation of the current analyses is that ORAL Surveillance was designed to assess non-inferiority of tofacitinib versus TNFi across the primary safety endpoints of adjudicated major adverse CV events and malignancies excluding NMSC; it was not powered to compare infection events across treatment groups. Multiple SIE, NSI and HZ events were reported as separate events if the event start dates differed; it is possible that some subsequent events may have overlapped with the initial event. The Cox regression analyses of risk factors for infections were exploratory in nature; interaction terms among risk factors and between risk factors and treatments were not included in the models, and associations identified between risk factors and events do not imply causality. Backward selection, while commonly used in analysing clinical trial data,30 may yield a biased relationship between selected covariates and the outcome, and CIs and p values may be underestimated.31 Further, the stability of the backward selection may be affected by a small number of events in some cases.30 Some risk factors evaluated in the Cox regression analyses, such as history of inflammatory bowel disease, chronic renal disease and heart failure, were associated with low N values; these results should be interpreted with caution. P values were reported with no adjustment for multiple comparisons, which may have increased the likelihood of false positive findings. Smoking status (eg, years smoked or years since quitting smoking) was not fully characterised. The IRs and risk of infections observed with tofacitinib and TNFi were not compared with that of placebo, csDMARDs or other bDMARDs. The tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day group included data from patients who had their dose reduced from 10 to 5 mg two times per day. Additionally, since TNFi drug (adalimumab or etanercept; not randomly assigned) was confounded by geographical region (North America or ROW), definitive conclusions cannot be made regarding risk of SIEs with tofacitinib versus etanercept or adalimumab, or for etanercept versus adalimumab.

Conclusions

Results of ORAL Surveillance showed dose-dependent increases in all infections, SIEs and NSIs with tofacitinib versus TNFi in patients aged≥50 years with ≥1 additional CV risk factor. The risk for all infections and SIEs increased with both tofacitinib doses versus TNFi, regardless of age, although an elevated risk with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus 5 mg two times per day and TNFi was most pronounced in patients aged≥65 vs 50–<65 years. The NNH for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day (recommended dosage for RA) versus TNFi for SIEs was 238 patient-years, meaning that over 5 years of treatment, 48 patients would need to be treated with tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day rather than TNFi to result in one additional SIE. ORAL Surveillance showed higher rates of MACE, malignancies (excluding NMSC) and venous thromboembolic events with tofacitinib versus TNFi (NNH (patient-years) for tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus TNFi: 567, 276 and 763 for MACE, malignancies and venous thromboembolic events, respectively, meaning over 5 years of treatment, 113, 55 and 153 patients, respectively, would need to be treated to have one additional event with tofacitinib 5 mg two times per day versus a TNFi).13 32 The current post hoc analysis revealed a higher risk of NSI and HZ with tofacitinib versus TNFi, and higher risk of SIE with tofacitinib 10 mg two times per day versus TNFi, particularly in patients aged≥65 years. These results should be carefully considered as part of shared decision-making between physicians and patients.

Acknowledgments

Select data in this manuscript were previously presented at ACR Convergence 2021. The authors would like to thank the patients, investigators and study teams involved in the study. The authors would like to thank Harry Shi from Pfizer for his guidance in the development of this manuscript. This study was sponsored by Pfizer. Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by Emma Mitchell, PhD, CMC Connect, McCann Health Medical Communications, and was funded by Pfizer, New York, New York, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–4).

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Contributors: DG conceived or designed the study and analysed the data. VP-R was involved in patient recruitment, acquired and analysed the data. A-SC analysed the data. All authors had access to the data, were involved in interpretation of data, and reviewed and approved the manuscript’s content before submission. A-RB accepts final responsibility for this work and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Pfizer.

Competing interests: A-RB has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Akros, Alfasigma, Amgen, Biogen, Eli Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB, has received speaker fees or honoraria from AbbVie, Alfasigma, Amgen, Angelini, AstraZeneca, Berlin-Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Teva, UCB and Zentiva, and has been a principal investigator in studies sponsored by Akros, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GSK, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. GC has received grants and/or research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Gema Pharma, Genzyme, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi-Genzyme, and has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Gema Pharma, Genzyme, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi-Genzyme. VP-R is an employee of Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición and is a principal investigator in studies sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer.

DLB is a member of the advisory board for: AngioWave, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, High Enroll, Janssen, Level Ex, Medscape Cardiology, Merck, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences, Stasys; Board of Directors: AngioWave (stock options), Boston VA Research Institute, Bristol Myers Squibb (stock), DRS.LINQ (stock options), High Enroll (stock), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, TobeSoft; Chair: Inaugural Chair, American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Acesion Pharma, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Boston Scientific (Chair, PEITHO trial), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Contego Medical (Chair, PERFORMANCE 2), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo; for the ABILITY-DM trial, funded by Concept Medical), Novartis, Population Health Research Institute; Rutgers University (for the NIH-funded MINT Trial); Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Chair, ACC Accreditation Oversight Committee), Arnold and Porter law firm (work related to Sanofi/Bristol-Myers Squibb clopidogrel litigation), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group (clinical trial steering committees), Cowen and Company, Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), K2P (Co-Chair, interdisciplinary curriculum), Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), MJH Life Sciences, Oakstone CME (Course Director, Comprehensive Review of Interventional Cardiology), Piper Sandler, Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees), Wiley (steering committee); Other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); Patent: Sotagliflozin (named on a patent for sotagliflozin assigned to Brigham and Women's Hospital who assigned to Lexicon; DLB/Brigham and Women's Hospital do not receive any income from this patent); Research Funding: Abbott, Acesion Pharma, Afimmune, Aker Biomarine, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beren, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Faraday Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Garmin, HLS Therapeutics, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Janssen, Javelin, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, Merck, Moderna, MyoKardia, NirvaMed, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Owkin, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Recardio, Regeneron, Reid Hoffman Foundation, Roche, Sanofi, Stasys, Synaptic, The Medicines Company, 89Bio; Royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, Endotronix, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Philips, SpectraWAVE, Svelte, Vascular Solutions; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; Unfunded Research: FlowCo, Takeda. He served as a member of the Steering Committee for ORAL Surveillance, with funding from Pfizer paid to Brigham and Women’s Hospital. CAC, DG and ABS are employees and stockholders of Pfizer. A-SC is an employee of Pfizer. GS is an employee of Syneos Health, who were paid contractors to Pfizer in the development of this manuscript. JEP has received grants and/or research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Seattle Genetics and UCB, and has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi and UCB. HS-K has acted as a consultant for, and been an advisor or review panel member for, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, MSD, Pfizer and UCB.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by ORAL Surveillance was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Council on Harmonisation, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and/or Independent Ethics Committee at each centre. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Croia C, Bursi R, Sutera D, et al. One year in review 2019: pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:347–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, et al. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2287–93. 10.1002/art.10524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Listing J, Gerhold K, Zink A. The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology 2013;52:53–61. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kelly C, Hamilton J. What kills patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatology 2007;46:183–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008;26:S35–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Du Pan SM, Dehler S, Ciurea A, et al. Comparison of drug retention rates and causes of drug discontinuation between anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:560–8. 10.1002/art.24463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singh JA, Cameron C, Noorbaloochi S, et al. Risk of serious infection in biological treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2015;386:258–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61704-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bechman K, Halai K, Yates M, et al. Nonserious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for rheumatology biologics register for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:1800–9. 10.1002/art.41754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Dartel SAA, Fransen J, Kievit W, et al. Difference in the risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, infliximab and etanercept: results from the Dutch rheumatoid arthritis monitoring (DREAM) registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:895–900. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dixon WG, Hyrich KL, Watson KD, et al. Drug-Specific risk of tuberculosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR). Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:522–8. 10.1136/ard.2009.118935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Botsios C, et al. Long-Term anti-TNF therapy and the risk of serious infections in a cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab in the GISEA registry. Autoimmun Rev 2012;12:225–9. 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pawar A, Desai RJ, Gautam N, et al. Risk of admission to hospital for serious infection after initiating tofacitinib versus biologic DMARDs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multidatabase cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2:e84–98. 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30137-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2022;386:316–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa2109927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. European Medicines Agency . Xeljanz® (tofacitinib): summary of product characteristics, 2020. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xeljanz-epar-product-information_en.pdf [Accessed 01 Sep 2021].

- 15. European Medicines Agency . EMA confirms Xeljanz to be used with caution in patients at high risk of blood clots, 2020. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/xeljanz-article-20-procedure-ema-confirms-xeljanz-be-used-caution-patients-high-risk-blood-clots_en.pdf [Accessed 01 Sep 2021].

- 16. Cohen SB, Tanaka Y, Mariette X, et al. Long-Term safety of tofacitinib up to 9.5 years: a comprehensive integrated analysis of the rheumatoid arthritis clinical development programme. RMD Open 2020;6:e001395. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Daly L. Simple SAS macros for the calculation of exact binomial and Poisson confidence limits. Comput Biol Med 1992;22:351–61. 10.1016/0010-4825(92)90023-g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Curtis JR, Winthrop K, O'Brien C, et al. Use of a baseline risk score to identify the risk of serious infectious events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during certolizumab pegol treatment. Arthritis Res Ther 2017;19:276. 10.1186/s13075-017-1466-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doran MF, Crowson CS, Pond GR, et al. Predictors of infection in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:2294–300. 10.1002/art.10529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Struyf T, Nuyts S, Tournoy J, et al. Burden of infections on older patients presenting to general practice: a registry-based study. Fam Pract 2021;38:166–72. 10.1093/fampra/cmaa105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Curtis JR, Schulze-Koops H, Takiya L, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in older and younger patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:390–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Winthrop KL, Citera G, Gold D, et al. Age-based (<65 vs ≥65 years) incidence of infections and serious infections with tofacitinib versus biological DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials and the US Corrona RA registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:134–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kremer JM, Bingham CO, Cappelli LC, et al. Postapproval comparative safety study of tofacitinib and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 5-year results from a United States-based rheumatoid arthritis registry. ACR Open Rheumatol 2021;3:173–84. 10.1002/acr2.11232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pfizer Inc . Xeljanz® (tofacitinib): highlights of prescribing information, 2020. Available: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=959 [Accessed 14 Oct 2021].

- 26. Jani M, Barton A, Hyrich K. Prediction of infection risk in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with biologics: are we any closer to risk stratification? Curr Opin Rheumatol 2019;31:285–92. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wiese AD, Griffin MR, Stein CM, et al. Opioid analgesics and the risk of serious infections among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a self-controlled case series study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:323–31. 10.1002/art.39462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Redeker I, Albrecht K, Kekow J, et al. Risk of herpes zoster (shingles) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis under biologic, targeted synthetic and conventional synthetic DMARD treatment: data from the German RABBIT register. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:41–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kivitz AJ, Cohen S, Keystone E, et al. A pooled analysis of the safety of tofacitinib as monotherapy or in combination with background conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in a phase 3 rheumatoid arthritis population. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;48:406–15. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chowdhury MZI, Turin TC. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam Med Community Health 2020;8:e000262. 10.1136/fmch-2019-000262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heinze G, Wallisch C, Dunkler D. Variable selection - A review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biom J 2018;60:431–49. 10.1002/bimj.201700067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charles-Schoeman C, Fleischmann R, Mysler E. The risk of venous thromboembolic events in patients with RA aged ≥50 years with ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor: results from a phase 3b/4 randomized safety study of tofacitinib vs TNF inhibitors [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73(Suppl 10):1941. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bălănescu AR, Citera G, Pascual-Ramos V. Incidence of infections in patients aged ≥ 50 years with RA and ≥ 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor: results from a Phase 3b/4 randomized safety study of tofacitinib vs TNF inhibitors [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73(Suppl 10):1684. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ard-2022-222405supp001.pdf (180.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.