Abstract

Vaccination is defined as the stimulation and development of the adaptive immune system by administering specific antigens. Vaccines' efficacy, in inducing immunity, varies in different societies due to economic, social, and biological conditions. One of the influential biological factors is gut microbiota. Cross-talks between gut bacteria and the host immune system are initiated at birth during microbial colonization and directly control the immune responses and protection against pathogen colonization. Imbalances in the gut microbiota composition, termed dysbiosis, can trigger several immune disorders through the activity of the adaptive immune system and impair the adequate response to the vaccination. The bacteria used in probiotics are often members of the gut microbiota, which have health benefits for the host. Probiotics are generally consumed as a component of fermented foods, affect both innate and acquired immune systems, and decrease infections. This review aimed to discuss the gut microbiota's role in regulating immune responses to vaccination and how probiotics can help induce immune responses against pathogens. Finally, probiotic-based oral vaccines and their efficacy have been discussed.

Keywords: probiotics, vaccine, vaccine efficacy, probiotic-based vaccines, gut microbiota, adaptive immunity

Introduction

Vaccination is defined as the stimulation and development of the adaptive immune system by the administration of specific antigens. Vaccines help prevent and eradicate the mortality and morbidity of numerous infectious diseases (1). Vaccine efficacy (VE) is described as the incidence proportion between the vaccinated and non-vaccinated populations (2) and varies in different societies based on economic, social, and biological conditions (3, 4). Several suggested economic and social determinants, such as country income status, living conditions and access to healthcare appear to act indirectly and non-specifically on VE. In contrast, many but not all biological factors, such as co-infections, malnutrition, and enteropathy, presumably, act directly and proximally on VE (5). Gut microbiota also plays a crucial role in the development and regulation of the immune system; hence, its composition might affect how individuals respond to vaccinations (6, 7).

Gut microbiota develops alongside host development and is affected by genetics and environmental factors, and is an integral part of the human body (8, 9). The microbiota interacts with the host in many ways. Cross-talks between gut bacteria and the host immune system are initiated at birth during microbial colonization (10). This interaction promotes the intestinal epithelial barrier, immune homeostasis, protects from pathogen colonization (11), and inhibits deleterious inflammatory reactions that would harm both the host and its gut microbiota (12). Gut lymph nodes, lamina propria, and epithelial cells (mucosal immune system) form a protective barrier for the integrity of the intestinal tract (13). Therefore the gut microbiota composition can affect the normal mucosal immune system (14).

During gut microbiota development, especially in early life, various factors can affect and alter its composition. For instance, the human gut changes considerably during the first 2 years of life as children grow from breast milk-dominated diets to solid foods and are exposed to vast numbers of bacterial species (15). Therefore undernourished children have been reported to have less mature gut microbiota compared to healthy children (16). Diet serves as a significant factor in gut microbiota composition in adults too. Various studies reported that a higher-fat diet in healthy adults appeared to be associated with unfavorable changes in gut microbiota, fecal metabolomics profiles, and plasma pro inflammatory factors, which might result in long-term adverse consequences for health (17–19). In addition, metabolic diseases such as diabetes can alter the gut microbiome and disrupt gut bacterial equilibrium (20). Other factors, including physical activity, mental health, and obesity may also affect gut microbiota composition (21–23).

Imbalances in the gut microbiota composition, termed dysbiosis, can trigger several immune disorders through the activity of the adaptive immune system (24). For example, recent studies on this subject reported that germ-free (GF) mice had a reduced number of Th1 and Th17 cells. Th17 cells, which are grouped as CD4+ effector T cells that secrete IL-17, play an important role in host defense against extracellular pathogens and the development of autoimmune diseases (25–27). Moreover, in dysbiotic gut microbiota, the number of inducible Foxp3 Helio-Tregs (iTregs) is reduced significantly in colonic lamina propria (28). Other studies indicate that excessive use of antibiotics disrupting gut microbiota hemostasis in young children might delay or impair the proper development of IgG response and immune memory that profoundly impacts adulthood (29). This review highlighted studies about the relationship between gut microbiota and related immune responses after vaccination and the impact of gut microbiota dysbiosis on VE.

Gut microbiota and vaccine efficacy

Cross-talk between the gut microbiome and the immune system by producing various metabolites and antimicrobial peptides directly regulates innate and adaptive immunity (30) and its failure to regulate inflammatory responses could increase the risk of developing inflammatory conditions in the gastrointestinal tract (31). Therefore the gut microbiota impacts the efficacy of various immune system-related interventions, including prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (32, 33), cancer immunotherapy (34–36), and dysregulation in gut microbial composition associated with autoantibodies production and autoimmune diseases (37–40). Several studies were designed to evaluate the relationship between gut microbiota and immune responses to assess vaccine efficiency. A study by Pulendran et al. showed that antibiotic consumption resulted in a 10,000-fold reduction in gut bacterial composition and reduced specific neutralization and binding antibody responses against the influenza vaccine, and a significant association between bacterial species and metabolic phenotypes in the gut was displayed in this study (41). Furthermore, infants who received oral polio vaccine (OPV), intramuscular tetanus-hepatitis B, and intradermal Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccines had detectable levels of Bifidobacterium longum (B. longum) and displayed higher specific T cell responses, serum IgG and fecal polio-specific IgA levels. In contrast, a higher relative abundance of Enterobacteriales and Pseudomonadales was associated with lower specific T cell responses and serum IgG levels (6, 42). Another study on infants receiving BCG, OPV, tetanus toxoid (TT), and hepatitis B virus confirmed the previous results that Bifidobacterium abundance in early infancy might increase the protective effects of vaccines by enhancing immunologic memory (7). The concurrent presence of non-polio enterovirus (NPEV) and oral polio vaccination can affect VE and reduce OPV seroconversion (43).

One of the critical factors in VE is the expression of Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) within 3 days after vaccination, which correlates to the amount of hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers 4 weeks after influenza vaccination (44, 45). TLR5 is a cell receptor for the recognition of flagellin and stimulates inflammatory signaling and immune responses (46). In addition, trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination of Trl5–/– mice resulted in reduced antibody titers. TLR5-mediated sensing of the microbiota also impacted antibody responses to the inactivated polio vaccine (47). NOD2 (Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2), an intracellular pathogen recognition sensor, is associated with the immune system and VE stimulation (48, 49). Recognition of symbiotic bacteria by NOD2 in CD11c-expressing phagocytes helps the mucosal adjuvant activity of cholera toxin (CT), as confirmed by a study on mice (50).

One of the most influential factors that lead to dysregulation of gut microbiota dysbiosis is antibiotic exposure (51). In 1 study, it is demonstrated that antibiotics-induced dysbiosis in infant mice (but not adults) leads to impaired antibody responses and promotes ex vivo cytokine recall responses (52). Antibiotic-treated mice models also showed impaired oral immunization in response to cholera toxin (53) and dysregulation in the generation of anti-viral macrophages, virus-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells, and antibody responses following respiratory influenza virus infection (54, 55). Gut dysbiosis induced by antibiotics significantly decreased the activation of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells and declined the level of memory of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in secondary lymphoid organs of the vaccinated animals (56). In a study on human adults with impaired microbiome induced by antibiotics, reduced antibody response to TIV in subjects with low pre-existing immunity to influenza virus was observed (41). However, adults receiving Rotavirus (RV), Pneumo23, and TT vaccines with antibiotics consumption showed increased fecal shedding of RV and changes in gut bacteria beta diversity which is associated with RV vaccine immunogenicity boosting (57). Although antibiotics consumption could not improve the immunogenicity of OPV in human infants, the reduction of enteropathy and pathogenic intestinal bacteria biomarkers were reported (58).

The composition of gut microbiota and its diversity are associated with the response of the immune system to vaccines. In this case, a study on specific pathogen-free layer chickens (SPF) showed that shifts in gut microbiota composition might result in changes in cell- and antibody-mediated immune responses to vaccination against influenza viruses (59, 60). Other experiments on adults receiving an HIV vaccine showed the immunogenicity of the vaccine was correlated with microbiota clusters (61). On the contrary, another study on human adults reported no differences in overall gut microbiota community diversity between humoral responders and non-responders to the oral Salmonella Typhi vaccine (62). Co-infection with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) and porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in pig models revealed that high growth outcomes were associated with several gut microbiome characteristics, such as increased bacterial diversity, increased relative abundance of Bacteroides pectinophilus, decreased Mycoplasmataceae species diversity, higher Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes ratios, increased relative abundance of the phylum Spirochaetes, reduced relative abundance of the family Lachnospiraceae, and increased Lachnospiraceae species (63). Diet is also influential on the gut microbiome and vaccine efficacy. A study showed that a gluten-free diet was associated with a reduced anti-tetanus IgG response, and it increased the relative abundance of the anti-inflammatory Bifidobacterium in the mice model (64).

Humans harbor several latent viruses, including cytomegalovirus (CMV) implicated in the modulation of host immunity (65). However, there is an insufficient understanding of the influence of lifelong persistent latent viral infections on the immune system (66). In a rhesus macaques model, subclinical CMV infection increased butyrate-producing bacteria and lower antibody responses to influenza vaccination (67).

Oral RV vaccines have the potential role in reducing the morbidity and mortality of RV infection that causes diarrhea-related death in children worldwide, but RV vaccines showed significantly lower efficacy in low-income countries (68, 69). A comparison between infants in India and Malawi and infants born in the UK showed that ORV immune response was significantly impaired among infants in the former. This result is linked with their gut microbiome composition, in which microbiota diversity was significantly higher among Malawian infants, while Indian infants had high Bifidobacterium abundance (70). Despite low RVV immunogenicity which was also reported in rural Zimbabwean infants, it was not associated with the composition or function of the early-life gut microbiome (71). Human gut microbiota transplanted pig models vaccinated with attenuated RVV showed significantly enhanced IFN-γ producing T cell responses and reduced regulatory T cells and cytokine production (72). Moreover, poor diet decreased total Ig and HRV-specific IgG and IgA antibody titers in serum or ileum and it increased fecal virus shedding titers in human infant microbiome transplanted pig models (57, 73, 74). In a study on rural Ghana's infants, RVV response was associated with an increased relative abundance of Streptococcus gallolyticus, decreased relative abundance of phylum Bacteroidetes and higher Enterobacteria/Bacteroides ratio (75). Another study reported that RVV response correlates with a higher relative abundance of bacteria belonging to Clostridium cluster XI and Proteobacteria (76). Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron is also associated with anti-rotavirus IgA titer (77). However, a study on Nicaraguan Infants reported a limited impact of gut microbial taxa on response to oral RVV (78).

Recent studies indicated that dysbiosis might be relevant in systemic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections. Khan et al. indicated an association between dysbiosis and severe inflammatory response in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Decreased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, induced by the depletion of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. prausnitzii), Bacteroides plebeius (B. plebeius), and Prevotella, which utilize fiber, and a relative increase in Bacteroidetes species is associated with raised serum IL-21 levels and better prognosis (79). A study on a cohort of 100 patients revealed that the composition of the gut microbiome in patients with COVID-19 correlates with disease severity, plasma concentrations of several inflammatory cytokines, and tissue-damaged associated chemokines. Patients with COVID-19 are recommended to consume beneficial microorganisms with immunomodulatory potentials, such as F. prausnitzii, Eubacterium rectale, and several Bifidobacterium species, and the dysbiosis persisted after the clearance of the virus (80, 81). Currently, controlling and preventing the spread of SARS-CoV2 infection is one of the critical challenges in the healthcare system. Vaccination is the best strategy to overcome this challenge (82). Among all recently proposed vaccines, an important note is to balance the humoral (neutralizing antibody) and T cell responses (83). Mucosal immunity is the most influential factor in preventing viral respiratory infections and response to vaccination. In this regard, the intestinal immune system is as important as the respiratory system's mucosal immunity (84). Thus, the intestinal immune system might be a promising approach for improving current SARS-CoV2 vaccination strategies (85). On the other hand, risk factors that reduce the immune system's defenses against SARS-CoV-2 infections could also reduce their responses to vaccination and increase vaccination's adverse effects. Thus gut dysbiosis is one of the mechanisms that can cause a pathological and impaired immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (86).

So far, most studies around vaccine efficacy and gut microbiota composition demonstrated that gut microbiota can influence vaccines' immunogenicity and the mucosal and acquired immunity against pathogens.

The effects of probiotics on vaccine efficacy

Probiotics are live commensal microorganisms that have positive benefits for the host that are generally consumed as a component of fermented foods. They have an impact on both innate and adaptive immune systems and decrease infections (87, 88). A meta-analysis comprising 1,979 adults showed that probiotics and prebiotics effectively promote immunogenicity by influencing seroconversion and seroprotection rates in adults vaccinated with influenza vaccines (89).

Bifidobacteria (BIF) is one of the probiotics and beneficial bacteria for human and animal health, having roles in the prevention of infection, modulation of lipid metabolism, and reduction of allergic symptoms by stimulating the host's mucosal immune system and systemic immune response (90, 91). Consumption of B. longum BB536 in newborns showed an increase in the number of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), a representative cytokine for T helper 1 response, secretion cells, and the ratio of IFN-γ/IL-4 secretion cells (92). In addition, a combination of B. longum BL999 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (L. rhamnosus) [LPR (CGMCC1.3724)] consumption after Hepatitis B vaccination resulted in improved antibody responses (93). The results of a study on adults who received seasonal influenza vaccines was the same. Probiotic consumption (B. longum bv. infantis CCUG 52,486, combined with a prebiotic gluco-oligosaccharide) could improve total antibody titers and seroprotection (94). Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12 and Lactobacillus paracasei (L. paracasei) 431 improved specific Antibody titers and seroconversion rates after influenza vaccination but there was no difference in INF-γ, IL-2, and IL-10 levels (95). In a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blinded prospective trial, the effect of probiotics [Bifidobacterium bifidum, B. infantis, B. longum, and Lactobacillus acidophilus (L. acidophilus)] on vaccination efficacy could not be proven statistically (96).

Strains of Lactobacillus are a subdominant component of the commensal human intestinal microbiota and are identified as a potential driving force in the development of the human immune system (97). They exert early immunostimulatory effects that may be directly linked to the initial inflammation responses in human macrophages (98). Chickens who received Lactobacillus spp as probiotics showed an increased major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II expression on macrophages and B cells. The number of CD4 + CD25 + T regulatory cells was also reduced in the spleen (99). In a study, the probiotic function of Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) was assessed and the results showed that fecal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) titer significantly increased in the probiotic group infants (100). Another study on chicken models showed that a mixture of probiotic Lactobacillus spp can enhance IFN-γ gene expression but does not influence antibody production after influenza vaccination (101). Consumption of probiotics containing Lactobacillus acidophilus; Lactobacillus plantarum; Pediococcus pentosaceus; Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Bacillus subtilis, and Bacillus licheniformis in broiler chickens resulted in the diminished adverse effect of live vaccine, reduced mortality rate, fecal shedding, and re-isolation of Salmonella Enteritidis (SE) from liver, spleen, heart, and cecum against SE vaccine (102). On this subject, oral administration of L.plantarum GUANKE (LPG) on mice models acted as a booster for COVID-19 vaccination and boosted >8-fold specific neutralization antibodies in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and >2-fold in serum (103). An in-vitro and in-silico study showed that L.plantarum could reduce inflammatory markers such as IFN-α, IFN-β, and IL-6 and block virus replication by interaction with SARS-CoV-2 helicase (104). L. acidophilus W37 (LaW37) with long-chain inulin (lcITF) was also used as a probiotic in a study on piglets and increased two-folded vaccine efficacy against Salmonella Typhimurium strains (STM) (105).

A pilot study on adults who received the influenza vaccine reported that L. rhamnosus GG (LGG) could be an influential adjuvant to improve influenza vaccine immunogenicity (106). LGG also improves T cell responses but not antibody production on human gut microbiota (HGM) transplanted gnotobiotic (Gn) pig model vaccinated with AttHRV (72). However, specific RV antibody production was stimulated in infants who received LGG (107). Another study confirms that the combination of L. acidophilus CRL431 and LGG enhanced IgA and IgM (but not IgG) production after OP vaccination (108).

Other types of probiotics have been studied on this subject as well. For example, Escherichia coli Nissle (EcN) 1917 was used to colonize antibiotic-treated and human infant fecal microbiota transplanted Gn piglets and immune response was evaluated to human Rotavirus (HRV). As a result, the humoral and cellular immune responses were enhanced, and EcN biofilm increased the frequencies of systemic memory and IgA + B cells (109, 110). Likewise, the Lactococcus lactis strain decreased severity and symptoms in volunteers with Dengue fever (DF) compared to the placebo group, promoted IFN-γ and TGF-β cytokines secretion, and reduced serum IgE and IL-4 cytokine levels in mice models (111, 112). Bacillus toyonensis (B. toyonensis) BCT-7112 was also enabled to improve the humoral immune response of ewes against the clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin (rETX) vaccine and boost higher neutralizing antibody titers (113). B. toyonensis and Saccharomyces boulardii also successfully boosted antibody production and expression of IFN-γ, IL2, and Bcl6 genes in Clostridium chauvoei vaccinated sheep (114). Likewise, Bacillus velezensis significantly reduced the pigeon circovirus (PiCV) viral load in the feces and spleen of pigeons and promoted TLR 2&4 expression (115). Fecal microbiome transplantation with Clostridium butyricum and Saccharomyces boulardii treatment in piglets not only improved plasma concentrations of IL-23, IL-17, IL-22 and specific antibodies against Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo) and Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2), but also decreased the inflammation levels and oxidative stress injury, and improved intestinal barrier function (116).

Although several studies reported a positive effect of Lactobacillus on VE, some studies yielded different results. For example, maternal LGG supplementation showed decreased specific antibody responses in tetanus, Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib), and pneumococcal conjugate (PCV7) vaccinated infants (117). Also, probiotic consumption containing Lactobacillus strains (L. paracasei and Lactobacillus casei (L. casei) 431 showed no effects on the immune response to the influenza vaccine but shortened the duration of respiratory symptoms (118). Another study on L. paracasei and MoLac-1 (heat-killed) supplemented diet reported the same results, and these probiotics could not boost immune responses after vaccination (119). A recent study also assessed LGG consumption impact on influenza vaccine efficacy in type 1 diabetic (T1D) children and reported no significant improvement in humoral response in the probiotic group (120). In conclusion, although some studies show that probiotics are inefficient in boosting the immune system and increasing vaccine efficacy, most studies demonstrated the positive effects of probiotics on promoting vaccine immunity and protecting the gut barrier simultaneously (Table 1).

Table 1.

Probiotics' effect on immune responses and vaccine efficacy.

| Probiotic strain | Participants | Vaccine | Effects of probiotics on vaccine response | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B. longum BB536 |

Human infants | DTP (diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus) | An increase in the ratio of IFN-γ/IL-4 secretion cells in the BB536 supplementation group | (92) |

| L. paracasei 431 | Human adults | Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine | No difference in A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strain-specific IgG/No difference in A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strain-specific IgA levels in saliva / No difference in seroconversion rates 3 w after vaccination | (118) |

| L. rhamnosus GG | Human pregnant women | Combined diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-Haemophilus influenza type b vaccine | Lower pneumococcal-specific IgG levels/Lower seroconversion rates for pneumococcal serotypes /Lower tetanus toxoid-specific IgG levels/No difference in Hib-specific IgG levels/Higher tolerogenic T regulatory (Treg) responses | (117) |

|

L. paracasaei MoLac-1 (heat-killed) |

Human adults | Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine | No differences in natural killer cell activity, neutrophil bactericidal or phagocytosis activity/No difference in IgA, IgG, and IgM levels/Higher H3N2 specific IgG levels/No difference in seroconversion rates | (119) |

| B. lactis BB-12 / L. paracasei 431 | Human adults | Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine | An increase in influenza-specific IgG levels/Higher seroconversion rates for IgG/Higher influenza-specific IgA levels in saliva /No differences in NK-cells activity, number of CD4+T-lymphocytes and phagocytosis/No differences in INF-γ, IL-2, and IL-10 levels | (95) |

| LGG and inulin | Human adults | Nasal attenuated trivalent influenza vaccine | Increased seroprotection rate to the H3N2 strain, but not to the H1N1 or B strain | (106) |

|

B. longum BL999 /L.rhamnosus LPR |

Human infants | Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), DTP | An improvement in HepB surface antibody responses in subjects receiving monovalent and a DTPa-HepB combination vaccine at 6 months but not those who received 3 monovalent doses | (93) |

| B. bifum / B.infantis/ B.longum/ L.acidophilus | Human infants | Measles-Mumps-Rubella-Varicella vaccine | Higher overall seroconversion rates/No difference in specific seroconversion rates for rubella, mumps, measles, varicella/No difference in the rate of treatment-related adverse effects between the two groups | (96) |

|

L. acidophilus CRL431/ L. rhamnosus GG |

Human adults | Oral polio vaccine | An increase in poliovirus neutralizing antibody levels/ Increase in poliovirus-specific IgA and IgM levels /No change in poliovirus-specific IgG levels | (108) |

| L. casei GG | Human infants | Oral rotavirus vaccine | Higher number of rotavirus-specific IgM secreting cells/ Higher IgA seroconversion rates /Higher IgM seroconversion rates | (107) |

| Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 | Ciprofloxacin (Cipro)-treated Gn piglets colonized with a defined commensal microbiota (DM) | Virulent human rotavirus (HRV) | An increase in the numbers of total immunoglobulin-secreting cells, HRV-specific antibody-secreting cells, activated antibody-forming cells, memory antibody-forming B cells, and naive antibody-forming B cells/ A Decreased in levels of pro-inflammatory but increased levels of immuno-regulatory cytokines and increased frequencies of Toll-like receptor-expressing cells | (109) |

| L.rhamnosus GG | Human gut microbiome transplanted neonatal Gn pig | Attenuated HRV vaccine | Significantly enhancement in HRV-specific IFN-γ producing T cell responses to the AttHRV vaccine. Neither doses of LGG significantly improved the protection rate, HRV-specific IgA and IgG antibody titers in serum, or IgA antibody titers in intestinal contents | (72) |

| L. plantarum | 24-Month-old children | - | An increase in fecal sIgA titer /A Significant positive correlation between TGF-β1,TNF-α, and fecal sIgA | (100) |

| B. longum + gluco-oligosaccharide | Human adults | Influenza seasonal vaccine | Significantly higher number of senescent (CD28–CD57+) helper T cells/Significantly higher plasma levels of anti-CMV IgG and a greater tendency for CMV seropositivity/Higher numbers of CD28–CD57+ helper T cells | (94) |

| L. plantarum GUANKE (LPG) | Mice | SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | Enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 neutralization antibodies production/A boost in specific neutralization antibodies >8-fold in bronchoalveolar lavage and >2-fold in sera when LPG was given immediately after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine inoculation /Persistence in T-cell responses | (103) |

| Lactococcus lactis strain plasma (LC-Plasma) | Human adults | Dengue fever (DF) | Significant reduction in the cumulative incidence days of DF-like symptoms/Significantly reduced severity score in the LC-Plasma group | (111) |

|

Lactobacillus

plantarum Probio-88 |

In vitro and in silico study | SARS-CoV-2 infection | A significant inhibition in the replication of SARS-CoV-2 and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels/A significant reduction in inflammatory markers such as IFN-α, IFN-β, and IL-6 | (104) |

| probiotic Lactobacillus | Chickens | Herpesvirus of turkeys vaccine | An increase in the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II on macrophages and B cells in spleen/A decrease in the number of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory | (99) |

| cells in the spleen/ higher expression of IFN-α at 21dpi in the spleen/A decrease in the expression of tumor growth factor (TGF)-β4 | ||||

| probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle (EcN) 1917 | Malnourished piglet model transplanted with human infant fecal microbiota (HIFM) | HRV vaccine | Increased frequencies of activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) and activated conventional dendritic cells (cDC)/increased frequencies of systemic activated and memory antibody-forming B cells and IgA+ B cells in the systemic tissues/Increase in the mean numbers of systemic and intestinal HRV-specific IgA antibody-secreting cells (ASCs), as well as HRV-specific IgA antibody titers in serum and small intestinal contents | (110) |

| Bacillus velezensis | Pigeons | Pigeon circovirus (PiCV) | Significant reduction in the PiCV viral load in the feces and spleen of pigeons/Up-regulation in Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), myxovirus resistance 1 (Mx1), signal transducers and activators of transcription 1 (STAT1), toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and 4 (TLR4)gene expression | (115) |

| Lactococcus lactis NZ1330 | BALB/c Mouse Model | Allergy to Amaranthus retroflexus pollens | Significantly reduction in the serum IgE level/Best performance in terms of improving allergies to Th1 and Treg responses | (112) |

| L.acidophilus; L.plantarum; Pediococcus pentosaceus; Saccharomyces cerevisiae; B.subtilis; B.licheniformis | Broiler chickens | Salmonella Enteritidis (SE) vaccine | Diminished the negative effect of live vaccine growth performance/reduced mortality rate, fecal shedding, and re-isolation of SE from liver, spleen, heart, and cecum | (102) |

| long-chain inulin (lcITF) and L.acidophilus W37 (LaW37) | Piglets | Salmonella Typhimurium strains (STM) | Enhanced vaccination efficacy by 2-fold /Higher relative abundance of Prevotellaceae and lower relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae in feces/Increased the relative abundance of fecal lactobacilli was correlated with higher fecal consistency | (105) |

| fecal microbiome+ Clostridium butyricum and Saccharomyces boulardii | Gpiglets | - | Increased the plasma concentrations of IL-23, IL-17, and IL-22, as well as the plasma levels of anti-M.hyo and anti-PCV2 antibodies/ Decreases in inflammation levels and oxidative stress injury, and improvement of intestinal barrier function | (116) |

| L.rhamnosus GG (LGG) | Patients with type 1 diabetes | Betapropiolactone- whole inactivated virus | Reduction in the inflammatory responses (i.e., IFN-γ, IL17A, IL-17F, IL-6, and TNF-α)/Significantly | (120) |

| production of IL-17F prior to and after (90 ± 7 days later) vaccination | ||||

| B. toyonensis BCT-7112T | Ewes of the Corriedale sheep | Recombinant Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin (rETX) | Higher neutralizing antibody titers/An increase in serum levels for total IgG anti-rETX/Increase IgG isotypes IgG1 and IgG2 /Higher cytokine mRNA transcription levels for IL-2, IFN-γ, and transcription factor Bcl6 | (113) |

| B. toyonensis and Saccharomyces boulardii | Sheep | Clostridium chauvoei vaccine | Significantly higher specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2 titers/Approximately 24- and 14-fold increases in total IgG levels/ Increased mRNA transcription levels of the IFN-γ, IL2, and Bcl6 genes | (114) |

Probiotic-based vaccines

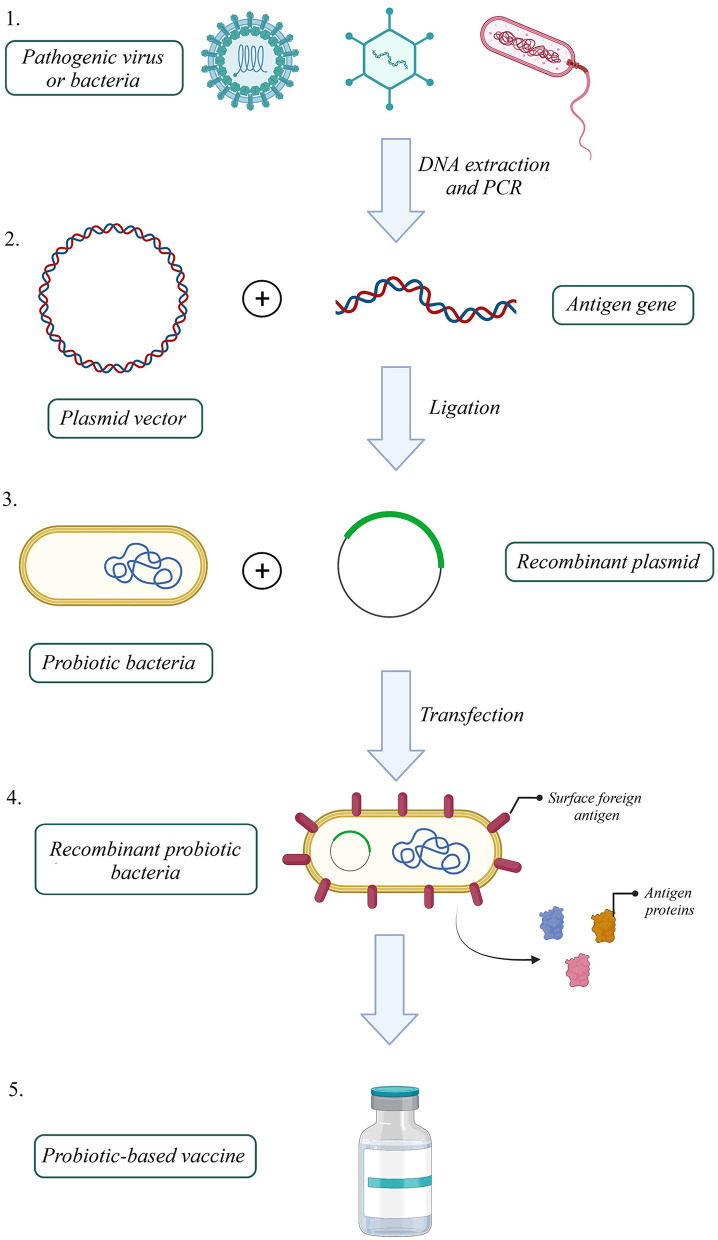

One efficient way to increase VE, produce a better immune response to an antigen, and reduce attenuated vaccine risk is to utilize recombinant antigens in gut microbiota vectors. Based on this idea, several probiotic-based vaccines were developed (Figure 1). For instance, the recombinant Streptococcus gordonii RJM4 vector has been used to express the N-terminal fragment of the S1 subunit of pertussis toxin (PT) as a SpaP/S1 fusion protein in mice. SIgA in saliva and IgG were detected, and long-term oral colonization and maintenance of recombinant protein were observed in these animal models (121). The B subunit of the heat-labile toxin (LTB) was one of the antigen targets that colonized Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) with episomal expression systems. Vaccinated mice with engineered B. subtilis via the oral route could be recognized and neutralize the native toxin, produced by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains in vitro (122). B. subtilis was also used as a shuttle for Clonorchis sinensis antigen. Compared with control groups, the results indicated that the vaccinated group could induce humoral and cellular immune responses successfully (123). Furthermore, another vaccine against ETEC strains, the probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) was used to express Stx B-subunits, OspA, and OspG protein antigens. This system could elicit hormonal responses but could not trigger selective T-cell responses against selected antigens (124). On the other hand, EcN 1917 expressing heterologous F4 or F4 and F18 fimbriae of ETEC improved anti-F4 and both anti-F4 and anti-F18 IgG immune responses (125).

Figure 1.

How to build a probiotic-based vaccine: 1. Extract the antigen gene from the pathogen, 2. Amplify the gene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), 3. Build a recombinant expression plasmid by ligating antigen gene into a proper plasmid, 4. Transfect recombinant plasmid into a probiotic host, 5. Select successfully transfected recombinant probiotic bacteria 6. Probiotic-based oral vaccines could be manufactured with a recombinant probiotic host expressing the pathogenic antigen (Created with BioRender.com).

Lactococcus lactis is a commonly used food-grade probiotic. To develop a vaccine against Helicobacter pylori, L. lactis expressing Helicobacter pylori urease subunit B (UreB) was used and results demonstrated that orally vaccinated mice elicited significant humoral immunity against gastric Helicobacter infection (126). Tang et al., designed a recombinant L. lactis expressing TGEV spike glycoprotein. Results on mice revealed induction of local mucosal immune responses and IgG and IgA antibodies production against TGEV spike glycoprotein (127). On this subject, L. lactis PppA (LPA+) recombinant strain containing pneumococcal protective protein A (LPA) in oral immunized mice showed mucosal and systemic antibody production against different serotypes of Streptococcus pneumonia (128). L. lactis was likewise used to deliver rotavirus spike-protein subunit VP8 in the mouse model. The serum of animals that received L. lactis with cell wall-anchored RV VP8 antigen could inhibit viral infection in vitro by 100% and vaccinated mice developed significant levels of intestinal IgA antibodies in vivo (129). The oral vaccine with L. Lactis expressing a recombinant fusion protein of M1 and HA2 proteins derived from the H9N2 virus successfully induces protective mucosal and systemic immunity in eighty 1-day-old chickens (130). Mohseni et al. employed L. lactis as a vector for expressing the codon-optimized human papillomavirus (HPV) - 16 E7 oncogenes, and it showed cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), and humoral responses after vaccination in healthy women volunteers with this probiotic-based vaccine (131). Similarly, another study on L. lactis expressing HPV codon-optimized E6 protein reported induction of humoral and cellular immunity and significantly increased intestinal mucosal lymphocytes, splenocytes, and vaginal lymphocytes in the vaccinated group compared to controls (132).

Lactobacillus casei strains are known for their immune stimulatory effect and have been used as probiotics for many years. A genetically engineered L. casei oral vaccine expressing dendritic cell (DC)-targeting peptide for Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) resulted in significantly elevated levels of anti-PEDV specific IgG and IgA antibody responses in mice and piglets (133, 134). Yoon et al. expressed poly-glutamic acid synthetase A (pgsA) protein from HPV-16 L2 in L. casei, and interestingly, L2-specific antibodies had cross-neutralizing activity against diverse HPV types in the mouse model (135). Recombinant L. casei was also used for immunizing piglets against TGEV. As a result, solid cellular response, switching from Th1 to Th2-based immune responses, and IL-17 expression in systemic and mucosal immunity was reported (136). In another study, α, ε, β1, and β2 toxoids of Clostridium perfringens expressed in L. casei ATCC 393 vector and elevated the levels of antigen-specific mucosa sIgA and sera IgG antibodies with exotoxin-neutralizing activity were seen in rabbit models (137). A different study used this probiotic expressing the VP2 protein of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) and reported induction of local mucosal and systemic immune responses in rainbow trout juveniles (138).

Other strains of lactobacillus are used in this technique as well. Oral recombinant Lactobacillus vaccine containing VP7 antigen of porcine rotavirus (PRV) showed stimulation in the differentiation of dendritic cells (DCs) in Peyer's patches (PPs) significantly, increased serum levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ and production of B220+ B cells in mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs). Also, it increased the titer levels of the VP7-specific antibodies in mice models (139). Recombinant L. Plantarum expressing H9N2 avian influenza virus used for specific pathogen-free (SPF) 3-week-old chickens and could elicit humoral and cellular immunity (140). Shi et al. showed excessive serum titers of hemagglutination-inhibition (HI) antibodies in mice, and robust T cell immune responses in both mouse and chicken H9N2 vaccinated models by Recombinant L. Plantarum (141). L. Plantarum NC8, expressing oral rabies vaccine G protein fused with a DC-targeting peptide (DCpep), resulted in more functional maturation of DCs and a strong Th1-biased immune response in mice (142). A recent study utilized L. Plantarum for developing SARS-CoV-2 food-grade oral vaccine. The results indicated that the spike gene could be efficiently expressed on the surface of recombinant L. Plantarum and displayed high antigenicity (143). As a novel approach for vaccination against SARS-Cov2, L. plantarum strain expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was used, and high yields for S protein were obtained in an engineered probiotic group in vitro (143). In murine models, Lactobacillus pentosus expressing D antigenic site of spike glycoprotein transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) could induce IgG and sIgA against this virus (144). Recombinant Lactobacillus rhamnosus that contains Koi herpesvirus (KHV) ORF81 protein in vaccinated fish was also successfully generated antigen-specific IgM with KHV-neutralizing activity (145). Another study used Lactobacillus acidophilus vector with the membrane-proximal external region from HIV-1 (MPER) and secreted interleukin-1ß (IL-1ß) or expressed the surface flagellin subunit C (FliC) as adjuvants, and reported as an improved vaccine efficacy and immune response against HIV-1 in mice (146). These studies demonstrated that probiotics have a potential role in acting as a shuttle for recombinant oral vaccines and successfully promoting the immune system against pathogens, and improving intestinal condition simultaneously.

Future perspective

There is no doubt that gut microbiota significantly impacts human metabolism and the immune system. Even further, some scientists consider gut microbiota as an endocrine organ in the human body. Probiotics are part of gut microbiota that have health benefits and promote immune responses. Based on the impact of gut mucosal immunity in the humoral immune response to vaccination, using probiotics as an immune booster next to oral vaccines can lead to better immunity, and probiotic-based recombinant vaccines promise a better generation of recombinant vaccines. Although a few human studies were performed on this subject, probiotics and probiotic-based recombinant vaccines' efficacy on immunity against pathogens is promising. Such a new oral vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection was developed by Symvivo Corporation (a Vancouver-based Biotech Company) using Bifidobacteria longum, for expressing spike protein (named bacTRL-Spike), and it is under investigation in phase 1 clinical trials (NCT04334980). However, more studies need to be performed to detect the effectiveness of probiotics and engineered probiotic vaccines in clinical trials and investigate their role in human immunological pathways to ensure their safety and durable immunity.

Author contributions

NK: literature search, writing, and drawing of figures. AD and SB: literature search. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Kocourkova A, Honegr J, Kuca K, Danova J. Vaccine ingredients: components that influence vaccine efficacy. Mini Rev Med Chem. (2017) 17:451–66. 10.2174/1389557516666160801103303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter TE. Evaluation of effectiveness of a vaccination program against an infectious disease at the population level. Am J Vet Res. (2001) 62:202–5. 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desselberger U. Differences of rotavirus vaccine effectiveness by country: likely causes and contributing factors. Pathogens. (2017) 6:65. 10.3390/pathogens6040065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang V, Jiang B, Tate J, Parashar UD, Patel MM. Performance of rotavirus vaccines in developed and developing countries. Hum Vaccin. (2010) 6:532–42. 10.4161/hv.6.7.11278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaslow DC. Force of infection: a determinant of vaccine efficacy? NPJ Vaccines. (2021) 6:51. 10.1038/s41541-021-00316-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huda MN, Lewis Z, Kalanetra KM, Rashid M, Ahmad SM, Raqib R, et al. Stool microbiota and vaccine responses of infants. Pediatrics. (2014) 134:e362–72. 10.1542/peds.2013-3937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huda MN, Ahmad SM, Alam MJ, Khanam A, Kalanetra KM, Taft DH, et al. Bifidobacterium abundance in early infancy and vaccine response at 2 years of age. Pediatrics. (2019) 143:1489. 10.1542/peds.2018-1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. (2014) 505:559–63. 10.1038/nature12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C, Yin A, Li H, Wang R, Wu G, Shen J, et al. Dietary modulation of gut microbiota contributes to alleviation of both genetic and simple obesity in children. EBioMedicine. (2015) 2:968–84. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adak A, Khan MR. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2019) 76:473–93. 10.1007/s00018-018-2943-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickard JM, Zeng MY, Caruso R, Núñez G. Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunol Rev. (2017) 279:70–89. 10.1111/imr.12567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Cerf-Bensussan N. Gut microbiota and development of the immune system. Med Sci (Paris). (2016) 32:961–7. 10.1051/medsci/20163211011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards JL, Yap YA, McLeod KH, Mackay CR, Mariño E. Dietary metabolites and the gut microbiota: an alternative approach to control inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Clin Transl Immunol. (2016) 5:e82. 10.1038/cti.2016.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi N, Li N, Duan X, Niu H. Interaction between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Mil Med Res. (2017) 4:14. 10.1186/s40779-017-0122-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, et al. Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science. (2012) 336:489–93. 10.1126/science.1219328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kortekangas E, Kamng'ona AW, Fan YM, Cheung YB, Ashorn U, Matchado A, et al. Environmental exposures and child and maternal gut microbiota in rural Malawi. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. (2020) 34:161–70. 10.1111/ppe.12623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan Y, Wang F, Yuan J, Li J, Jiang D, Zhang J, et al. Effects of dietary fat on gut microbiota and faecal metabolites, and their relationship with cardiometabolic risk factors: a 6-month randomised controlled-feeding trial. Gut. (2019) 68:1417–29. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bibbò S, Ianiro G, Giorgio V, Scaldaferri F, Masucci L, Gasbarrini A, et al. The role of diet on gut microbiota composition. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2016) 20:4742–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang M, Yang XJ. Effects of a high fat diet on intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. (2016) 22:8905–9. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karusheva Y, Koessler T, Strassburger K, Markgraf D, Mastrototaro L, Jelenik T, et al. Short-term dietary reduction of branched-chain amino acids reduces meal-induced insulin secretion and modifies microbiome composition in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. (2019) 110:1098–107. 10.1093/ajcn/nqz191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uemura M, Hayashi F, Ishioka K, Ihara K, Yasuda K, Okazaki K, et al. Obesity and mental health improvement following nutritional education focusing on gut microbiota composition in Japanese women: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:3291–302. 10.1007/s00394-018-1873-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motiani KK, Collado MC, Eskelinen JJ, Virtanen KA, LÖyttyniemi E, Salminen S, et al. Exercise Training Modulates Gut Microbiota Profile and Improves Endotoxemia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2020) 52:94–104. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasini E, Corsetti G, Assanelli D, Testa C, Romano C, Dioguardi FS, et al. Effects of chronic exercise on gut microbiota and intestinal barrier in human with type 2 diabetes. Minerva Med. (2019) 110:3–11. 10.23736/S0026-4806.18.05589-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature. (2016) 535:75–84. 10.1038/nature18848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirota K, Ahlfors H, Duarte JH, Stockinger B. Regulation and function of innate and adaptive interleukin-17-producing cells. EMBO Rep. (2012) 13:113–20. 10.1038/embor.2011.248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dutzan N, Kajikawa T, Abusleme L, Greenwell-Wild T, Zuazo CE, Ikeuchi T, et al. A dysbiotic microbiome triggers T(H)17 cells to mediate oral mucosal immunopathology in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:eaat0797. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat0797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji J, Ge X, Chen Y, Zhu B, Wu Q, Zhang J, et al. Daphnetin ameliorates experimental colitis by modulating microbiota composition and T(reg)/T(h)17 balance. FASEB J. (2019) 33:9308–22. 10.1096/fj.201802659RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. (2013) 341:569–73. 10.1126/science.1241165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng MY, Inohara N, Nuñez G. Mechanisms of inflammation-driven bacterial dysbiosis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. (2017) 10:18–26. 10.1038/mi.2016.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baradaran Ghavami S, Pourhamzeh M, Farmani M, Raftar SKA, Shahrokh S, Shpichka A, et al. Cross-talk between immune system and microbiota in COVID-19. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) 15:1281–94. 10.1080/17474124.2021.1991311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vitetta L, Briskey D, Alford H, Hall S, Coulson S. Probiotics, prebiotics and the gastrointestinal tract in health and disease. Inflammopharmacology. (2014) 22:135–54. 10.1007/s10787-014-0201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu H, Gu R, Li W, Zhou W, Cong Z, Xue J, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG attenuates tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-induced bone loss in male mice via gut-microbiota-dependent anti-inflammation. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. (2019) 10:2040622319860653. 10.1177/2040622319860653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klatt NR, Cheu R, Birse K, Zevin AS, Perner M, Noël-Romas L, et al. Vaginal bacteria modify HIV tenofovir microbicide efficacy in African women. Science. (2017) 356:938–45. 10.1126/science.aai9383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. (2018) 359:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillère R, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. (2018) 359:91–7. 10.1126/science.aan3706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baruch EN, Youngster I, Ben-Betzalel G, Ortenberg R, Lahat A, Katz L, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science. (2021) 371:602–9. 10.1126/science.abb5920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruff WE, Dehner C, Kim WJ, Pagovich O, Aguiar CL, Yu AT, et al. Pathogenic autoreactive T and B cells cross-react with mimotopes expressed by a common human gut commensal to trigger autoimmunity. Cell Host Microbe. (2019) 26:100–13.e8. 10.1016/j.chom.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.López P, de Paz B, Rodríguez-Carrio J, Hevia A, Sánchez B, Margolles A, et al. Th17 responses and natural IgM antibodies are related to gut microbiota composition in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:24072. 10.1038/srep24072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qian X, Liu YX, Ye X, Zheng W, Lv S, Mo M, et al. Gut microbiota in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: characteristics, biomarker identification, and usefulness in clinical prediction. BMC Genomics. (2020) 21:286. 10.1186/s12864-020-6703-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyake S, Kim S, Suda W, Oshima K, Nakamura M, Matsuoka T, et al. Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of patients with multiple sclerosis, with a striking depletion of species belonging to clostridia XIVa and IV clusters. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0137429. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagan T, Cortese M, Rouphael N, Boudreau C, Linde C, Maddur MS, et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell. (2019) 178:1313–28.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullié C, Yazourh A, Thibault H, Odou MF, Singer E, Kalach N, et al. Increased poliovirus-specific intestinal antibody response coincides with promotion of Bifidobacterium longum-infantis and Bifidobacterium breve in infants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Res. (2004) 56:791–5. 10.1203/01.PDR.0000141955.47550.A0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Praharaj I, Parker EPK, Giri S, Allen DJ, Silas S, Revathi R, et al. Influence of Nonpolio Enteroviruses and the Bacterial Gut Microbiota on Oral Poliovirus Vaccine Response: A Study from South India. J Infect Dis. (2019) 219:1178–86. 10.1093/infdis/jiy568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huleatt JW, Nakaar V, Desai P, Huang Y, Hewitt D, Jacobs A, et al. Potent immunogenicity and efficacy of a universal influenza vaccine candidate comprising a recombinant fusion protein linking influenza M2e to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. Vaccine. (2008) 26:201–14. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakaya HI, Wrammert J, Lee EK, Racioppi L, Marie-Kunze S, Haining WN, et al. Systems biology of vaccination for seasonal influenza in humans. Nat Immunol. (2011) 12:786–95. 10.1038/ni.2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tahoun A, Jensen K, Corripio-Miyar Y, McAteer S, Smith DGE, McNeilly TN, et al. Host species adaptation of TLR5 signalling and flagellin recognition. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:17677. 10.1038/s41598-017-17935-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh JZ, Ravindran R, Chassaing B, Carvalho FA, Maddur MS, Bower M, et al. TLR5-mediated sensing of gut microbiota is necessary for antibody responses to seasonal influenza vaccination. Immunity. (2014) 41:478–92. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lupfer C, Thomas PG, Kanneganti TD. Nucleotide oligomerization and binding domain 2-dependent dendritic cell activation is necessary for innate immunity and optimal CD8+ T Cell responses to influenza A virus infection. J Virol. (2014) 88:8946–55. 10.1128/JVI.01110-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deng W, Xie J. NOD2 signaling and role in pathogenic mycobacterium recognition, infection and immunity. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2012) 30:953–63. 10.1159/000341472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim D, Kim YG, Seo SU, Kim DJ, Kamada N, Prescott D, et al. Nod2-mediated recognition of the microbiota is critical for mucosal adjuvant activity of cholera toxin. Nat Med. (2016) 22:524–30. 10.1038/nm.4075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vangay P, Ward T, Gerber Jeffrey S, Knights D. Antibiotics, pediatric dysbiosis, and disease. Cell Host Microbe. (2015) 17:553–64. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lynn MA, Tumes DJ, Choo JM, Sribnaia A, Blake SJ, Leong LEX, et al. Early-life antibiotic-driven dysbiosis leads to dysregulated vaccine immune responses in mice. Cell Host Microbe. (2018) 23:653–60.e5. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim D, Kim YM, Kim WU, Park JH, Núñez G, Seo SU. Recognition of the microbiota by Nod2 contributes to the oral adjuvant activity of cholera toxin through the induction of interleukin-1β. Immunology. (2019) 158:219–29. 10.1111/imm.13105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ichinohe TI, Pang K, Kumamoto Y, Peaper DR, Ho JH, Murray TS, et al. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:5354–9. 10.1073/pnas.1019378108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abt MC, Osborne LC, Monticelli LA, Doering TA, Alenghat T, Sonnenberg GF, et al. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity. (2012) 37:158–70. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nadeem S, Maurya SK, Das DK, Khan N, Agrewala JN. Gut dysbiosis thwarts the efficacy of vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:726. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michael H, Langel SN, Miyazaki A, Paim FC, Chepngeno J, Alhamo MA, et al. Malnutrition decreases antibody secreting cell numbers induced by an oral attenuated human rotavirus vaccine in a human infant fecal microbiota transplanted gnotobiotic pig model. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:196. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grassly NC, Praharaj I, Babji S, Kaliappan SP, Giri S, Venugopal S, et al. The effect of azithromycin on the immunogenicity of oral poliovirus vaccine: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial in seronegative Indian infants. Lancet Infect Dis. (2016) 16:905–14. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30023-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yitbarek A, Astill J, Hodgins DC, Parkinson J, Nagy É, Sharif S. Commensal gut microbiota can modulate adaptive immune responses in chickens vaccinated with whole inactivated avian influenza virus subtype H9N2. Vaccine. (2019) 37:6640–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yitbarek A, Alkie T, Taha-Abdelaziz K, Astill J, Rodriguez-Lecompte JC, Parkinson J, et al. Gut microbiota modulates type I interferon and antibody-mediated immune responses in chickens infected with influenza virus subtype H9N2. Benef Microbes. (2018) 9:417–27. 10.3920/BM2017.0088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cram JA, Fiore-Gartland AJ, Srinivasan S, Karuna S, Pantaleo G, Tomaras GD, et al. Human gut microbiota is associated with HIV-reactive immunoglobulin at baseline and following HIV vaccination. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0225622. 10.1371/journal.pone.0225622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eloe-Fadrosh EA, McArthur MA, Seekatz AM, Drabek EF, Rasko DA, Sztein MB, et al. Impact of oral typhoid vaccination on the human gut microbiota and correlations with s. Typhi-specific immunological responses. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e62026. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Constance LA, Thissen JB, Jaing CJ, McLoughlin KS, Rowland RR, Serão NV, et al. Gut microbiome associations with outcome following co-infection with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) and porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in pigs immunized with a PRRS modified live virus vaccine. Vet Microbiol. (2021) 254:109018. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2021.109018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kihl P, Krych L, Deng L, Hansen LH, Buschard K, Skov S, et al. Effect of gluten-free diet and antibiotics on murine gut microbiota and immune response to tetanus vaccination. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0266719. 10.1371/journal.pone.0266719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. (2010) 20:202–13. 10.1002/rmv.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brodin P, Jojic V, Gao T, Bhattacharya S, Angel CJ, Furman D, et al. Variation in the human immune system is largely driven by non-heritable influences. Cell. (2015) 160:37–47. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Santos Rocha C, Hirao LA, Weber MG, Méndez-Lagares G, Chang WLW, Jiang G, et al. Subclinical Cytomegalovirus Infection Is Associated with Altered Host Immunity, Gut Microbiota, and Vaccine Responses. J Virol. (2018) 92:e00167–18. 10.1128/JVI.00167-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2012) 12:136–41. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fischer Walker CL, Black RE. Rotavirus vaccine and diarrhea mortality: quantifying regional variation in effect size. BMC Public Health. (2011) 11 Suppl 3:S16. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parker EP, Bronowski C, Sindhu KNC, Babji S, Benny B, Carmona-Vicente N, et al. Impact of maternal antibodies and microbiota development on the immunogenicity of oral rotavirus vaccine in African, Indian, and European infants. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:1–14. 10.1038/s41467-021-27074-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robertson RC, Church JA, Edens TJ, Mutasa K, Geum HM, Baharmand I, et al. The fecal microbiome and rotavirus vaccine immunogenicity in rural Zimbabwean infants. Vaccine. (2021) 39:5391–400. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wen K, Tin C, Wang H, Yang X, Li G, Giri-Rachman E, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG enhanced Th1 cellular immunity but did not affect antibody responses in a human gut microbiota transplanted neonatal gnotobiotic pig model. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e94504. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miyazaki A, Kandasamy S, Michael H, Langel SN, Paim FC, Chepngeno J, et al. Protein deficiency reduces efficacy of oral attenuated human rotavirus vaccine in a human infant fecal microbiota transplanted gnotobiotic pig model. Vaccine. (2018) 36:6270–81. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Srivastava V, Deblais L, Huang H-C, Miyazaki A, Kandasamy S, Langel S, et al. Reduced rotavirus vaccine efficacy in protein malnourished human-faecal-microbiota-transplanted gnotobiotic pig model is in part attributed to the gut microbiota. Benef Microbes. (2020) 11:733–51. 10.3920/BM2019.0139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harris VC, Armah G, Fuentes S, Korpela KE, Parashar U, Victor JC, et al. Significant correlation between the infant gut microbiome and rotavirus vaccine response in rural ghana. J Infect Dis. (2017) 215:34–41. 10.1093/infdis/jiw518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harris V, Ali A, Fuentes S, Korpela K, Kazi M, Tate J, et al. Rotavirus vaccine response correlates with the infant gut microbiota composition in Pakistan. Gut Microbes. (2018) 9:93–101. 10.1080/19490976.2017.1376162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robertson RC, Church JA, Edens TJ, Mutasa K, Geum HM, Baharmand I, et al. The gut microbiome and rotavirus vaccine immunogenicity in rural Zimbabwean infants. medRxiv. 2021:2021.03.24.21254180. (2021). 10.1101/2021.03.24.21254180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fix J, Chandrashekhar K, Perez J, Bucardo F, Hudgens MG, Yuan L, et al. Association between Gut Microbiome Composition and Rotavirus Vaccine Response among Nicaraguan Infants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2020) 102:213–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khan M, Mathew BJ, Gupta P, Garg G, Khadanga S, Vyas AK, et al. Gut Dysbiosis and IL-21 Response in Patients with Severe COVID-19. Microorganisms. (2021) 9:1292. 10.3390/microorganisms9061292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yeoh YK, Zuo T, Lui GC, Zhang F, Liu Q, Li AY, et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. (2021) 70:698–706. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shenoy S. Gut microbiome, Vitamin D, ACE2 interactions are critical factors in immune-senescence and inflammaging: key for vaccine response and severity of COVID-19 infection. Inflamm Res. (2022) 71:13–26. 10.1007/s00011-021-01510-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cao X. COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:269–70. 10.1038/s41577-020-0308-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen J. Vaccine designers take first shots at COVID-19. In: American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2020). 10.1126/science.368.6486.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fu Y, Cheng Y, Wu Y. Understanding SARS-CoV-2-mediated inflammatory responses: from mechanisms to potential therapeutic tools. Virol Sin. (2020) 35:266–71. 10.1007/s12250-020-00207-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moradi-Kalbolandi S, Majidzadeh AK, Abdolvahab MH, Jalili N, Farahmand L. The role of mucosal immunity and recombinant probiotics in SARS-CoV2 vaccine development. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. (2021) 13:1239–53. 10.1007/s12602-021-09773-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen J, Vitetta L, Henson JD, Hall S. The intestinal microbiota and improving the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccinations. J Funct Foods. (2021) 87:104850. 10.1016/j.jff.2021.104850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2014) 11:506–14. 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kanauchi O, Andoh A, AbuBakar S, Yamamoto N. Probiotics and paraprobiotics in viral infection: clinical application and effects on the innate and acquired immune systems. Curr Pharm Des. (2018) 24:710–7. 10.2174/1381612824666180116163411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lei WT, Shih PC, Liu SJ, Lin CY, Yeh TL. Effect of probiotics and prebiotics on immune response to influenza vaccination in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. (2017) 9:1175. 10.3390/nu9111175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Majamaa H, Isolauri E. Probiotics: a novel approach in the management of food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (1997) 99:179–85. 10.1016/S0091-6749(97)70093-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Makioka Y, Tsukahara T, Ijichi T, Inoue R. Oral supplementation of Bifidobacterium longum strain BR-108 alters cecal microbiota by stimulating gut immune system in mice irrespectively of viability. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. (2018) 82:1180–7. 10.1080/09168451.2018.1451738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu BB, Yang Y, Xu X, Wang WP. Effects of Bifidobacterium supplementation on intestinal microbiota composition and the immune response in healthy infants. World J Pediatr. (2016) 12:177–82. 10.1007/s12519-015-0025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Soh SE, Ong DQ, Gerez I, Zhang X, Chollate P, Shek LP, et al. Effect of probiotic supplementation in the first 6 months of life on specific antibody responses to infant Hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccine. (2010) 28:2577–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Przemska-Kosicka A, Childs CE, Enani S, Maidens C, Dong H, Dayel IB, et al. Effect of a synbiotic on the response to seasonal influenza vaccination is strongly influenced by degree of immunosenescence. Immun Ageing. (2016) 13:6. 10.1186/s12979-016-0061-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rizzardini G, Eskesen D, Calder PC, Capetti A, Jespersen L, Clerici M. Evaluation of the immune benefits of two probiotic strains Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis, BB-12® and Lactobacillus paracasei ssp paracasei, L casei 431® in an influenza vaccination model: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr. (2012) 107:876–84. 10.1017/S000711451100420X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Youngster I, Kozer E, Lazarovitch Z, Broide E, Goldman M. Probiotics and the immunological response to infant vaccinations: a prospective, placebo controlled pilot study. Arch Dis Child. (2011) 96:345–9. 10.1136/adc.2010.197459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O'Callaghan J, O'Toole PW. Lactobacillus: host-microbe relationships. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. (2013) 358:119–54. 10.1007/82_2011_187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rocha-Ramírez LM, Pérez-Solano RA, Castañón-Alonso SL, Moreno Guerrero SS, Ramírez Pacheco A, García Garibay M, et al. Probiotic lactobacillus strains stimulate the inflammatory response and activate human macrophages. J Immunol Res. (2017) 2017:4607491. 10.1155/2017/4607491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bavananthasivam J, Alizadeh M, Astill J, Alqazlan N, Matsuyama-Kato A, Shojadoost B, et al. Effects of administration of probiotic lactobacilli on immunity conferred by the herpesvirus of turkeys vaccine against challenge with a very virulent Marek's disease virus in chickens. Vaccine. (2021) 39:2424–33. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kusumo PD, Bela B, Wibowo H, Munasir Z, Surono IS. Lactobacillus plantarum IS-10506 supplementation increases faecal sIgA and immune response in children younger than two years. Benef Microbes. (2019) 10:245–52. 10.3920/BM2017.0178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Alqazlan N, Astill J, Taha-Abdelaziz K, Nagy É, Bridle B, Sharif S. Probiotic lactobacilli enhance immunogenicity of an inactivated H9N2 influenza virus vaccine in chickens. Viral Immunol. (2021) 34:86–95. 10.1089/vim.2020.0209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.El-Shall NA, Awad AM, El-Hack MEA, Naiel MA, Othman SI, Allam AA, et al. The simultaneous administration of a probiotic or prebiotic with live Salmonella vaccine improves growth performance and reduces fecal shedding of the bacterium in Salmonella-challenged broilers. Animals. (2019) 10:70. 10.3390/ani10010070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xu J, Ren Z, Cao K, Li X, Yang J, Luo X, et al. Boosting Vaccine-Elicited Respiratory Mucosal and Systemic COVID-19 Immunity in Mice With the Oral Lactobacillus plantarum. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:789242. 10.3389/fnut.2021.789242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rather IA, Choi S-B, Kamli MR, Hakeem KR, Sabir JS, Park Y-H, et al. Potential Adjuvant Therapeutic Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum Probio-88 Postbiotics against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines. (2021) 9:1067. 10.3390/vaccines9101067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lépine AF, Konstanti P, Borewicz K, Resink J-W, de Wit NJ, Vos Pd, et al. Combined dietary supplementation of long chain inulin and Lactobacillus acidophilus W37 supports oral vaccination efficacy against Salmonella typhimurium in piglets. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:1–13. 10.1038/s41598-019-54353-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Davidson LE, Fiorino AM, Snydman DR, Hibberd PL. Lactobacillus GG as an immune adjuvant for live-attenuated influenza vaccine in healthy adults: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2011) 65:501–7. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Isolauri E, Joensuu J, Suomalainen H, Luomala M, Vesikari T. Improved immunogenicity of oral D x RRV reassortant rotavirus vaccine by Lactobacillus casei GG. Vaccine. (1995) 13:310–2. 10.1016/0264-410X(95)93319-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.de Vrese M, Rautenberg P, Laue C, Koopmans M, Herremans T, Schrezenmeir J. Probiotic bacteria stimulate virus-specific neutralizing antibodies following a booster polio vaccination. Eur J Nutr. (2005) 44:406–13. 10.1007/s00394-004-0541-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Michael H, Paim FC, Langel SN, Miyazaki A, Fischer DD, Chepngeno J, et al. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 Enhances Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in a Ciprofloxacin-Treated Defined-Microbiota Piglet Model of Human Rotavirus Infection. mSphere. (2021) 6:e00074–21. 10.1128/mSphere.00074-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Michael H, Paim FC, Miyazaki A, Langel SN, Fischer DD, Chepngeno J, et al. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 administered as a dextranomar microsphere biofilm enhances immune responses against human rotavirus in a neonatal malnourished pig model colonized with human infant fecal microbiota. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0246193. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Khor C-S, Tsuji R, Lee H-Y. Nor'e S-S, Sahimin N, Azman A-S, et al. Lactococcus lactis strain plasma intake suppresses the incidence of dengue fever-like symptoms in healthy malaysians: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. (2021) 13:4507. 10.3390/nu13124507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vasiee A, Falah F, Sankian M, Tabatabaei-Yazdi F, Mortazavi SA. Oral immunotherapy using probiotic ice cream containing recombinant food-grade Lactococcus lactis which inhibited allergic responses in a BALB/c mouse model. J Immunol Res. (2020) 1–12. 10.1155/2020/2635230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Santos FDS, Ferreira MRA, Maubrigades LR, Gonçalves VS, de Lara APS, Moreira C, et al. Bacillus toyonensis BCT-7112(T) transient supplementation improves vaccine efficacy in ewes vaccinated against Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin. J Appl Microbiol. (2021) 130:699–706. 10.1111/jam.14814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Santos FDS, Maubrigades LR, Gonçalves VS, Alves Ferreira MR, Brasil CL, Cunha RC, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of short-term supplementation with Bacillus toyonensis BCT-7112(T) and Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 in sheep vaccinated with Clostridium chauvoei. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. (2021) 237:110272. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2021.110272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tsai CY, Hu SY, Santos H, Catulin G, Tayo L, Chuang K. Probiotic supplementation containing Bacillus velezensis enhances expression of immune regulatory genes against pigeon circovirus in pigeons (Columba livia). J Appl Microbiol. (2021) 130:1695–704. 10.1111/jam.14893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xiang Q, Wu X, Pan Y, Wang L, Cui C, Guo Y, et al. Early-life intervention using fecal microbiota combined with probiotics promotes gut microbiota maturation, regulates immune system development, and alleviates weaning stress in piglets. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:503. 10.3390/ijms21020503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Licciardi PV, Ismail IH, Balloch A, Mui M, Hoe E, Lamb K, et al. Maternal Supplementation with LGG Reduces Vaccine-Specific Immune Responses in Infants at High-Risk of Developing Allergic Disease. Front Immunol. (2013) 4:381. 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jespersen L, Tarnow I, Eskesen D, Morberg CM, Michelsen B, Bügel S, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, L casei 431 on immune response to influenza vaccination and upper respiratory tract infections in healthy adult volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Am J Clin Nutr. (2015) 101:1188–96. 10.3945/ajcn.114.103531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Akatsu H, Arakawa K, Yamamoto T, Kanematsu T, Matsukawa N, Ohara H, et al. Lactobacillus in jelly enhances the effect of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2013) 61:1828–30. 10.1111/jgs.12474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bianchini S, Orabona C, Camilloni B, Berioli MG, Argentiero A, Matino D, et al. Effects of probiotic administration on immune responses of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes to a quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2020) 16:86–94. 10.1080/21645515.2019.1633877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lee SF, Halperin SA, Wang H, MacArthur A. Oral colonization and immune responses to Streptococcus gordonii expressing a pertussis toxin S1 fragment in mice. FEMS Microbiol Lett. (2002) 208:175–8. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Paccez JD, Nguyen HD, Luiz WB, Ferreira RC, Sbrogio-Almeida ME, Schuman W, et al. Evaluation of different promoter sequences and antigen sorting signals on the immunogenicity of Bacillus subtilis vaccine vehicles. Vaccine. (2007) 25:4671–80. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang X, Chen W, Tian Y, Mao Q, Lv X, Shang M, et al. Surface display of Clonorchis sinensis enolase on Bacillus subtilis spores potentializes an oral vaccine candidate. Vaccine. (2014) 32:1338–45. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Remer KA, Bartrow M, Roeger B, Moll H, Sonnenborn U, Oelschlaeger TA. Split immune response after oral vaccination of mice with recombinant Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 expressing fimbrial adhesin K88. Int J Med Microbiol. (2009) 299:467–78. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ou B, Jiang B, Jin D, Yang Y, Zhang M, Zhang D, et al. Engineered recombinant Escherichia coli probiotic strains integrated with F4 and F18 fimbriae cluster genes in the chromosome and their assessment of immunogenic efficacy in vivo. ACS Synth Biol. (2020) 9:412–26. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gu Q, Song D, Zhu M. Oral vaccination of mice against Helicobacter pylori with recombinant Lactococcus lactis expressing urease subunit B. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. (2009) 56:197–203. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00566.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tang L, Li Y. Oral immunization of mice with recombinant Lactococcus lactis expressing porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus spike glycoprotein. Virus Genes. (2009) 39:238–45. 10.1007/s11262-009-0390-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Villena J, Medina M, Racedo S, Alvarez S. Resistance of young mice to pneumococcal infection can be improved by oral vaccination with recombinant Lactococcus lactis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. (2010) 43:1–10. 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60001-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Marelli B, Perez AR, Banchio C, de Mendoza D, Magni C. Oral immunization with live Lactococcus lactis expressing rotavirus VP8 subunit induces specific immune response in mice. J Virol Methods. (2011) 175:28–37. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sha Z, Shang H, Miao Y, Huang J, Niu X, Chen R, et al. Recombinant Lactococcus Lactis Expressing M1-HA2 Fusion Protein Provides Protective Mucosal Immunity Against H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus in Chickens. Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:153. 10.3389/fvets.2020.00153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]