Abstract

The variable 56-kDa major outer membrane protein of Orientia tsutsugamushi is the immunodominant antigen in human scrub typhus infections. We developed a rapid immunochromatographic flow assay (RFA) for the detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies to O. tsutsugamushi. The RFA employs a truncated recombinant 56-kDa protein from the Karp strain as the antigen. The performance of the RFA was evaluated with a panel of 321 sera (serial bleedings of 85 individuals suspected of scrub typhus) which were collected in the Pescadore Islands, Taiwan, from 1976 to 1977. Among these 85 individuals, IgM tests were negative for 7 cases by both RFA and indirect fluorescence assay (IFA) using Karp whole-cell antigen. In 29 cases specific responses were detected by the RFA earlier than by IFA, 44 cases had the same detection time, and 5 cases were detected earlier by IFA than by RFA. For IgG responses, 4 individuals were negative with both methods, 37 cases exhibited earlier detection by RFA than IFA, 42 cases were detected at the same time, and 2 cases were detected earlier by IFA than by RFA. The sensitivities of RFA detection of antibody in sera from confirmed cases were 74 and 86% for IgM and IgG, respectively. When IgM and IgG results were combined, the sensitivity was 89%. A panel of 78 individual sera collected from patients with no evidence of scrub typhus was used to evaluate the specificity of the RFA. The specificities of the RFA were 99% for IgM and 97% for IgG. The sensitivities of IFA were 53 and 73% for IgM and IgG, respectively, and were 78% when the results of IgM and IgG were combined. The RFA test was significantly better than the IFA test for the early detection of antibody to scrub typhus in primary infections, while both tests were equally sensitive with reinfected individuals.

Scrub typhus infection is caused by the gram-negative bacterium Orientia tsutsugamushi. It accounts for up to 23% of all febrile episodes in areas of the Asia-Pacific region where scrub typhus is endemic and can cause up to 35% mortality if left untreated (4, 5). Diagnosis of scrub typhus is generally based on the clinical presentation and the history of the patient. However, differentiating scrub typhus from other acute tropical febrile illnesses, such as leptospirosis, murine typhus, malaria, dengue fever, and viral hemorrhagic fevers, is difficult because their symptoms are very similar. Previous serological assays, which include the indirect fluorescence assay (IFA), indirect immunoperoxidase assay, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and dot blot assays, use rickettsiae grown in host cells or extracts of purified bacteria as antigens (3, 9, 11, 19, 32, 33, 36, 37). Sera from 95 to 99% of patients with scrub typhus recognize a 56-kDa protein of O. tsutsugamushi (12, 20, 21, 28) which comprises 10 to 15% of the total rickettsial cellular protein content (15, 27). The well-known antigenic differences that exist among various strains of O. tsutsugamushi depend largely on variations in the 56-kDa antigen (27, 35).

PCR amplification of the 56-kDa protein gene has been demonstrated to be a reliable method for diagnosing scrub typhus (14, 17). Furthermore, different genotypes associated with different Orientia serotypes can be identified by analysis of variable regions of this gene without isolation of the organism (10, 13, 14, 16, 17, 25, 34). However, gene amplification requires a sophisticated instrument and labile reagents which are generally not available in most rural medical facilities.

A recombinant 56-kDa protein from the Boryong strain fused with maltose binding protein was shown to be suitable for diagnosis of scrub typhus when used in ELISA and passive hemagglutination tests (20, 21). Recently a truncated recombinant major outer protein antigen of the Karp strain (r56) was expressed and refolded to a structure very similar to its native form (6). A commercially available ELISA for immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG detection using r56 has been developed and evaluated previously (22). The ELISA format is very convenient for large-scale testing in a pathology laboratory, and the assay takes about 50 min to perform.

Here we describe the development of a simple and rapid immunochromatographic flow assay (RFA) that also employed r56 as the antigen. The RFA consists of a unique double-sided lateral nitrocellulose strip, which can simultaneously detect the presence of IgM and IgG (8). The performance of this rapid test was compared to that of IFA by using Orientia strain Karp whole cells as antigen with 321 sera from suspected scrub typhus patients. The sensitivity of RFA is much higher than that of IFA. In general, RFA can detect scrub typhus-specific antibodies in serial bleedings earlier than IFA. The specificity of the RFA is >97% based on the results of 78 non-scrub typhus-infected patient sera. This test does not require any special equipment, and there is no need for sophisticated technical training. The procedure for RFA takes less than 15 min to finish and is much simpler to perform than the commercial dip-stick assay reported previously (36). This product is suitable for rural clinical sites and doctors' offices where advanced medical support is limited.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of r56.

The procedures for the production of r56 were essentially the same as those described previously, with slight modifications (6). Because ampicillin cannot be used for GMP production, a kanamycin resistance gene was inserted into the original plasmid, pWM1, which carried the truncated 56-kDa protein gene of the O. tsutsugamushi Karp strain. The kanamycin resistance gene was cut from pUC-4K (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) using the restriction enzyme EcoRI and ligated into pWM1 (6). The final construct, pWM2, contained both the new kanamycin resistance gene and the original ampicillin resistance gene and the truncated Karp strain 56-kDa protein gene. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Novagene, Madison, Wis.) was transformed with pWM2. Cell pellets were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (buffer A), and disrupted with a microfluidizer (Model M110F; Microfluidics Corp., Newton, Mass.). Pelleted inclusion bodies from the cell lysate were sequentially extracted with 2 M urea in buffer A and 2% sodium deoxycholate in buffer A. Finally the extracted pellets were dissolved in 8 M urea in buffer A and loaded onto a Toyopearl DEAE-650M ion exchange column (TosoHaas, Montgomeryville, Pa.) which was equilibrated with buffer B (6 M urea in buffer A). Bound r56 was eluted with 0.1 N NaCl in buffer B. The absorbance of the pooled r56 fractions at 280 nm was measured, and the pool was diluted with buffer B to a final concentration of 0.67 mg/ml. Refolding of r56 in 6 M urea in buffer A was achieved by sequential dialysis with 4 M urea and 2 M urea in buffer A and finally with buffer A only. The truncated recombinant antigen was easy to refold and formed much less aggregate upon storage than improperly folded antigen.

Concept of RFA.

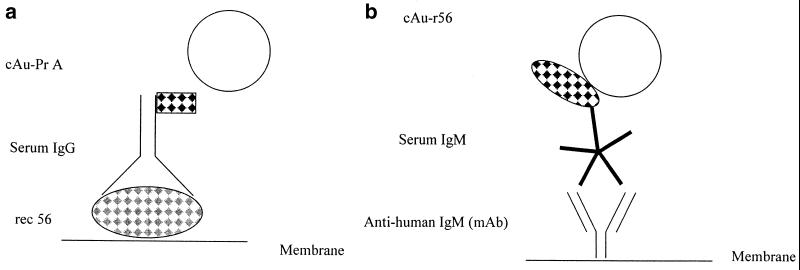

The Scrub Typhus Rapid Flow Assay is a double-sided lateral flow strip assay (8). This assay detects IgM antibody on one side of the strip and IgG antibody on the other side. In the IgG test, the recombinant protein r56 is deposited on the nitrocellulose membrane as the capture antigen line. The detecting reagent, which is purified staphylococcal protein A conjugated to colloidal gold, is dried on a conjugate pad. During the assay, specific IgG antibodies in the patient's serum are captured on the membrane and are detected with the redissolved gold conjugate as shown in Fig. 1a. The IgM test utilizes a monoclonal antibody to human IgM bound on the nitrocellulose as the IgM capture reagent and a recombinant antigen r56 conjugated to colloidal gold dried on a pad as the detecting reagent (Fig. 1b). Anti-human IgM monoclonal antibody was purchased from BioSpecific, Emeryville, Calif. Conjugates used in the assay were prepared in-house by labeling r56 antigen or protein A with colloidal gold. A control line is also included to ensure that sufficient liquid has passed over the capture lines. The detection conjugates dried on the conjugate pads dissolved upon contact with the diluted patient sample, and the antibodies in the serum react with them. The complex then wicks past the test and control lines on the nitrocellulose membrane.

FIG. 1.

(a) The scrub typhus IgG test consists of the recombinant protein r56 (rec 56) as the capture reagent and gold-labeled protein A (cAu-PrA) as the detecting reagent. (b) The scrub typhus IgM test consists of a monoclonal antibody (mAb) to human IgM as the capture reagent and a colloidal gold-conjugated recombinant antigen r56 (cAu-r56) as the detecting reagent.

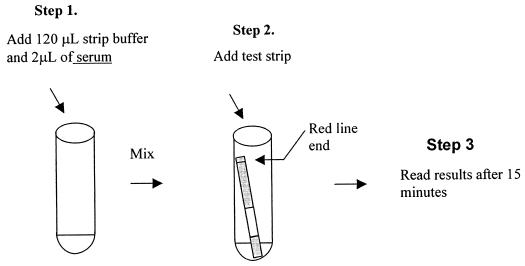

RFA test procedure.

A volume of 120 μl of strip buffer is added to a clear 12- by 75-mm tube, followed by addition of 2 μl of the test serum. The tube contents are mixed by gently tapping the side of the tube to allow for the uniform distribution of the serum. Following the addition of a test strip into the tube, the diluted serum wicks upward on the strip. The test result is read after 15 min (Fig. 2). A positive result appears as a purple-red band. The absence of a band suggests a negative result. If the control lines fail to appear, the assay must be repeated.

FIG. 2.

RFA procedure.

IFA test.

IFA titers were determined as described previously (2). The IFA antigen was a 20% yolk sac suspension of the Karp strain. All conjugates were standardized by the method of Beutner et al. prior to use (1). Stained slides were examined at ×400 magnification. Endpoint titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution at which rickettsiae exhibited 1+ fluorescence. Titers equal to or larger than 40 were considered positive, and those less than 40 were negative. The key serum dilution, 1:40, was established after testing 51 volunteers of comparable age and occupation.

Human sera.

Patient sera from the Pescadore Islands of Taiwan were obtained from a Chinese military garrison stationed there during 1976 and 1977 and were stored at −80°C (2). The initial clinical diagnosis of scrub typhus was confirmed by the demonstration of rising anti-rickettsial IFA titers (2). Cases for which serial bleedings were available were tested. The time intervals between serial bleedings varied, but most of them were collected 1 week apart. Sera from non-scrub typhus patients were from a reference panel (36). Sera from patients without a history of scrub typhus and diagnosed with the following diseases (number of sera in parentheses) were included in the negative control panel: bartonellosis (four), cholera (two), leptospirosis (three), malaria (three), rheumatoid arthritis (three), tularemia (nine), typhoid (six), anti-nuclear antibody (twenty-one), and others of unknown origin (twenty-seven).

The experiments reported herein were conducted according to the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, DHHS Publication (NIH) 86-23 (1985) (16a). This study was conducted in accordance with human subject protocols approved by the Naval Medical Research Center Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

RESULTS

The performance of the RFA was evaluated with a panel of 78 individual sera collected from non-scrub typhus patients and with a panel of 321 sera (serial bleedings of 85 individuals with clinically diagnosed scrub typhus) that were collected in the Pescadore Islands from 1976 to 1977. The intervals between serial bleedings were about 1 week. The comparison of RFA performance with that of IFA is summarized in Table 1. Earlier or later detection means 1 week before or 1 week after the other test showed positive. Among all 85 cases, 50 cases exhibited 1-week earlier detection with RFA for either IgM or IgG, 60 cases at the same time, and 7 cases exhibited 1-week later detection. Based on these results, RFA is more sensitive than IFA in detecting early antibody responses. Similarly, when the antibody level decreased in convalescent bleedings, the RFA showed positive in longer duration than IFA (Tables 2 through 4). For IgM responses, RFA detected the first specific responses earlier than IFA in 29 cases, had the same initial detection time in 44 cases, and had become reactive later than IFA in 5 cases. Seven cases were negative by both methods. For IgG tests, RFA detected the specific responses earlier than the IFA in 37 cases, had the same detection time in 42 cases, and had later detection times than IFA in 2 cases. Of the 85 suspected cases, 81 cases were confirmed as scrub typhus infection. The four unconfirmed cases showed negative results by both RFA and IFA. Two of these cases were isolation negative, and for the other two cases no isolation was attempted (2).

TABLE 1.

Summary of comparison between RFA and IFA

| Assay result | No. of patients positive for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgM or IgG | |

| RFA positive before IFA | 29 | 37 | 50 |

| RFA and IFA positive concurrently | 44 | 42 | 60 |

| RFA positive after IFA | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Both tests negative | 7 | 4 | 8 |

TABLE 2.

Scrub typhus antibodies detected earlier with RFA than with IFAa

| Patient | Days after onset of illness | IFA titers of:

|

RFA detection of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | ||

| MAK134 (7/6/76) | 1 | − | − | − | − |

| 8 | − | − | + | + | |

| 15 | 320 | 80 | + | + | |

| 21 | 640 | 160 | + | + | |

| 32 | 80 | 320 | − | + | |

| MAK251 (7/17/77) | 6 | − | − | + | + |

| 11 | 640 | 320 | + | + | |

| 20 | 320 | 160 | + | + | |

| 26 | 320 | 80 | + | + | |

| 27 | 1,280 | 160 | + | + | |

| 60 | − | 1,280 | + | + | |

| MAK116 (6/5/76) | 3 | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | 80 | − | + | + | |

| 17 | 320 | 160 | + | + | |

| 23 | 640 | 320 | + | + | |

| 31 | 160 | 320 | + | + | |

| 64 | − | 1,280 | + | + | |

| MAK153 (7/22/76) | 3 | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | − | − | − | − | |

| 17 | 320 | − | + | + | |

| 24 | 640 | − | + | + | |

| 30 | 640 | − | + | + | |

| 46 | − | 640 | + | + | |

| MAK213 (6/24/77) | 5 | − | − | + | − |

| 12 | 320 | 80 | + | + | |

| 36 | 160 | 160 | + | + | |

| 56 | − | 320 | + | + | |

Date of onset is listed in parentheses as month/day/year. IFA negative (−), titer of <40; RFA negative (−), no visible lines.

TABLE 4.

Scrub typhus antibodies detected later with RFA than with IFAa

| Patient | Days after onset of illness | IFA titer of:

|

RFA detection of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | ||

| MAK107 (5/25/76) | 7 | 40 | − | − | + |

| 14 | 640 | 640 | + | + | |

| 21 | 80 | 40 | + | + | |

| 28 | − | 320 | + | + | |

| 35 | − | 160 | + | + | |

| 65 | − | 640 | − | + | |

| MAK127 (6/22/76) | 6 | 80 | − | − | − |

| 13 | 2,560 | 320 | + | + | |

| 27 | 320 | 80 | + | + | |

| 34 | 640 | 640 | + | + | |

| 65 | − | 2,560 | − | + | |

| MAK128 (6/25/76) | 7 | 80 | 40 | − | + |

| 22 | − | 320 | − | + | |

| 86 | − | 320 | − | + | |

| MAK151 (7/19/76) | 18 | 80 | − | − | + |

| 25 | − | − | − | + | |

| 32 | − | 80 | + | + | |

| 79 | − | 320 | − | + | |

| 242 | − | 160 | − | − | |

| MAK216 (6/30/77) | 4 | − | 40 | − | − |

| 22 | 80 | 80 | + | + | |

| 54 | − | 160 | + | + | |

Date of onset is listed in parentheses as month/day/year. IFA negative (−), titer of <40; RFA negative (−), no visible lines.

Tables 2 through 4 list some representative cases illustrating these results. Cases where RFA showed earlier detection than IFA were further grouped into three categories (Table 2): IgG and IgM were detected earlier (MAK134 and MAK251), IgG was detected earlier but IgM was detected simultaneously (MAK116 and MAK153), and IgM was detected earlier while IgG was detected simultaneously (MAK213). Specific antibodies could be detected as early as 5 days after the onset of illness. Although the RFA generally showed positive 1 week earlier than IFA, in two cases RFA-positive results were observed 2 to 3 weeks earlier than IFA-positive results (MAK153 and MAK114, not listed in Table 2). In 19 cases, both IgG and IgM were detected by RFA and IFA at the same time (Table 3). The five cases in which IgM or IgG were reactive earlier by IFA than by RFA are shown in Table 4. In these five cases, the IFA titers of the IFA-positive, RFA-negative sera were never higher than 80. For all the sera tested in this study, there was no single serum of which the IFA titer was higher than 80 and the RFA test was negative.

TABLE 3.

Scrub typhus antibodies detected at the same time with RFA and IFAa

| Patient | Days after onset of illness | IFA titers of:

|

RFA detection of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | ||

| MAK129 (6/27/76) | 5 | − | − | − | − |

| 19 | 1,280 | 80 | + | + | |

| 26 | 640 | 80 | + | + | |

| 33 | 640 | 320 | + | + | |

| 57 | 40 | 640 | + | + | |

| MAK145 (7/14/76) | 1 | − | − | − | − |

| 8 | 160 | 80 | + | + | |

| 15 | 320 | 320 | + | + | |

| 21 | 640 | 320 | + | + | |

| 29 | 320 | 160 | + | + | |

| 85 | 320 | 160 | + | + | |

| MAK148 (7/17/76) | 13 | 2,560 | 1,280 | + | + |

| 20 | 1,280 | 1,280 | + | + | |

| 34 | 160 | 640 | + | + | |

| 81 | − | 640 | + | + | |

| MAK241 (7/11/77) | 7 | − | − | − | − |

| 15 | 320 | 160 | + | + | |

| 22 | 40 | 80 | + | + | |

| 29 | 320 | 160 | + | + | |

| 67 | 320 | 640 | + | + | |

| MAK254 (7/23/77) | 4 | − | − | − | − |

| 11 | 640 | 160 | + | + | |

| 25 | 320 | 160 | + | + | |

| 52 | − | 80 | + | + | |

Date of onset is listed in parentheses as month/day/year. IFA negative (−), titer of <40; RFA negative (−), no visible lines.

Simultaneous detection of IgM and IgG with RFA allows the estimation of both primary and secondary infections. Table 5 lists results with some cases classified as secondary infections. In these cases either IgG was present earlier than IgM or IgM was absent by both RFA and IFA. Reinfections or secondary infections with scrub typhus are common in regions where scrub typhus is endemic and can be distinguished from primary infections by their earlier onset of IgG antibodies and no production or very low levels of IgM.

TABLE 5.

Detection by RFA and IFA of scrub typhus antibodies in secondary infectionsa

| Patient | Days after onset of illness | IFA titers of:

|

RFA detection of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | ||

| MAK121 (6/11/76) | 10 | − | 40 | − | − |

| 18 | − | 320 | + | + | |

| 24 | 160 | 1,280 | + | + | |

| 31 | − | 640 | − | + | |

| MAK132 (6/29/76) | 7 | − | 320 | − | + |

| 14 | − | 640 | − | + | |

| 21 | − | 640 | − | + | |

| 30 | − | 2,560 | + | + | |

| 69 | − | 2,560 | − | + | |

| MAK139 (7/10/76) | 9 | − | 80 | − | + |

| 16 | 640 | 320 | + | + | |

| 24 | 1,280 | 320 | + | + | |

| 30 | 1,280 | 640 | + | + | |

| 61 | − | 640 | + | + | |

| 251 | − | − | − | − | |

| MAK152 (7/24/76) | 0 | − | 40 | − | + |

| 7 | − | 320 | + | + | |

| 14 | − | 2,560 | + | + | |

| 20 | − | 640 | + | + | |

| MAK168 (7/30/76) | 3 | − | 640 | − | + |

| 10 | − | 1,280 | − | + | |

| 24 | − | 2,560 | − | + | |

Date of onset is listed in parentheses as month/day/year. IFA negative (−), titer of <40; RFA negative (−), no visible lines.

The sensitivities of RFA detection with sera from confirmed cases were 74% (237 out of 321) and 86% (277 out of 321) for IgM and IgG, respectively (Table 6). When IgM and IgG were used together, the sensitivity was 89% (284 out of 321). In the past, the “gold standard” for scrub typhus diagnosis was IFA. The sensitivities of IFA detection with sera from confirmed cases were 53% (169 out of 321) and 73% (233 out of 321) for IgM and IgG, respectively, and 78% (251 out of 321) when IgM and IgG results were both considered. The P values for all comparisons of RFA versus IFA were calculated by Fisher's exact test to be the following: IgM, P < 0.0001; IgG, P < 0.0002; IgG and IgM, P = 0.0007. Consequently, RFA was substantially more sensitive than IFA. The specificity of the RFA was 99% for IgM and 97% for IgG, as determined from the results of 78 non-scrub typhus patient sera. Actually, only two malaria patients were positive for IgG by RFA, and one of the same patients was positive for IgM by RFA.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of efficiency of IFA and RFA

| Assay | % Sensitivity (no. positive/no. negative)a

|

% Specificity (no. negative/no. positive)d

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgG and IgM | IgM | IgG | IgG and IgM | |

| IFA (Karp)b | 53 (169/152) | 73 (233/88) | 78 (251/70) | ND | ND | ND |

| RFA (r56)c | 74 (237/84) | 86 (277/44) | 89 (284/37) | 99 (77/1) | 97 (76/2) | 97 (76/2) |

Total number of serum tested was 321. The P values for all comparisons of RFA versus IFA were calculated by Fisher's exact test (IgM, P < 0.0001; IgG, P < 0.0002; IgG and IgM, P = 0.0007).

The 95% confidence interval for IFA sensitivity was as follows: IgM, 48 to 58%; IgG, 68 to 78%; IgG and IgM, 74 to 83%.

The 95% confidence interval for RFA sensitivity was as follows: IgM, 69 to 79%; IgG, 82 to 90%; IgG and IgM, 85 to 92%.

The total number of negative control sera was 78. The 95% confidence interval for RFA specificity was as follows: IgM, 97 to 100%; IgG, 94 to 100%; IgG and IgM, 94 to 100%. ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

Antigenic differences in Orientia are an important consideration for serodiagnosis of scrub typhus, because at the present time, the number of scrub typhus serotypes is not completely known. The variable major outer membrane protein (vOmp) of O. tsutsugamushi used for serotyping varies from 53 to 63 kDa, even among isolates from the same country (24). Both unique and cross-reactive domains exist in different homologs of this protein (24, 28). Consequently, the selection of a vOmp antigen from an appropriate strain or whether to use multiple strains is a basic consideration in the design of diagnostic tests for scrub typhus. DNA sequence analysis of vOmp genes from different strains identified at least four variable domains and four conserved domains on this protein (26). Choi et al. generated a series of vOmp gene deletion fragments from various strains and concluded that the variable domain I (VD I) is important in homologous antibody responses and that antigenic domains II (AD II), AD III, and VD IV are important in the heterologous antibody responses of mice immunized with those deletion fragments (7). However, the nature of human responses to different serotypes of vOmp is still not known. Previously we showed that r56 from the Karp strain exhibited broad cross-reactivity with rabbit immune sera of seven other antigenic prototype strains (Gilliam, Kato, TA716, TA678, TA763, TH1817, and TA686) (6). Furthermore, patients from Thailand and Australia reacted very well to Karp r56 in an ELISA (22). At the present time we believe that the r56 from the Karp strain is suitable for testing sera over widely separated regions.

The Karp strain r56 is truncated at both the N and C termini. It contains all the variable domains (VD I, VD II, VD III, and VD IV) and all the antigenic domains except AD I, which is only partially included (amino acids 80 to 113). Choi et al. showed that VD I was highly immunogenic and that antibodies to the N-terminal portion were predominant in mice (7). However, when patient sera from the Pescadore Islands were tested against series of overlapping peptides which encompass the whole open reading frame of the Karp strain 56-kDa protein, no strong epitopes were found in this region (Ching et al., unpublished results). Although r56 contains VD I, the antibodies against VD I may not be dominant in human responses. The high sensitivity of the RFA that uses Karp r56 suggests that most of the strains from the Pescadore Islands contain antigenic domains that are cross-reactive with the Karp strain. The restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the isolates from the Pescadore Islands identified five different types (10, 34). Furthermore, some patient sera had higher IFA titers against whole-cell antigens of strain Gilliam or Kato than against Karp (2). The strain variations may account for those cases in which antibody detection was earlier with IFA than with RFA (Table 4). In the IFA test, total antibodies against all rickettsial proteins were measured. In the RFA test, only antibodies against the truncated 56-kDa protein were measured. Antibodies other than those against the 56-kDa protein may be less serotype specific, thus contributing to the sensitivity of IFA for heterologous strains. Bourgeois et al. found that IgM responses were relatively more strain specific by IFA in both primary and secondary infections (2). The IgM detection by RFA may be more sensitive to differences in the antibody responses due to antigenically different strains because r56 lacks the conserved cross-reactive antigens which are present in the whole-organism assays.

The performance of the RFA was evaluated with 321 scrub typhus patient sera and 78 serum specimens from non-scrub typhus patients. The results of these 399 sera showed that RFA is more sensitive in serodiagnosis than the traditional gold standard IFA assay. When the results of IgG and IgM were combined, the sensitivity was 89% for RFA and only 78% for IFA (P = 0.0007), based on confirmed cases. The higher sensitivity of RFA leads to the earlier detection of antibodies in acute-phase patient sera and later detection in convalescent-phase sera compared to those of IFA. Differences in sensitivity between the RFA and IFA may be due to the different formats of the assays. The specificity of RFA is excellent (>97%). The supposed false positives observed for two malaria patients reacted with r56 like true positives by Western blot analysis. This could be due to true cross-reactivity of anti-malarial or anti-scrub typhus antibodies with different antigens or a dual infection with malaria and scrub typhus. Reinfection with scrub typhus is relatively common in areas where scrub typhus is highly endemic (2). The specificity of RFA may actually be as high as 100%. Therefore, the high sensitivity of the RFA is not at the expense of its specificity. At the present time, the commercially available dot blot immunologic assay (Dip-S-Ticks; Integrated Diagnostics, Baltimore, Md.) requires tissue culture-grown, Renografin density gradient-purified whole-cell antigen (36). The procedure of the Dip-S-Ticks assay needs a temperature-controlled water bath, several refrigerated reagents, and multiple steps to get reliable results. The procedure for RFA is simpler than that of the Dip-S-Tick assay and only takes 15 min to accomplish. The stability of RFA test strips was evaluated under high-temperature stress at 37 and 50°C over a period of 1 to 12 weeks. The predicted shelf lives using the results of four negative and six positive sera are 1 to 2 years at 22°C and at least 2 years at 4°C. RFA should present fewer problems for storage and transportation and test reproducibilities than tests which use whole rickettsiae. We believe that the RFA is particulary suitable for use in field settings where medical support is limited. To improve upon the already broad reactivity of RFA for the diagnosis of scrub typhus, we are producing r56 antigens from strains Gilliam and Kato to be included in the RFA for future evaluation. Both strains were shown to be antigenically distinct. They were isolated from geographic areas different from that of the Karp strain (Karp from New Guinea, Gilliam from Burma, Kato from Japan). It will be necessary to test other strains to confirm the increased broad reactivity of the combined antigen test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by Naval Medical Research and Development Command, research work units 62787A.001.01.EJX.1295.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beutner E H, Sepulveda M R, Barnett E E. Quantitative studies of immunofluorescent staining. Relationships of characteristics of unabsorbed antihuman IgG complexes to their specific and nonspecific staining properties in an indirect test for antinuclear factors. Bull W H O. 1968;39:587–606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourgeois A L, Olson J G, Fang R C, Huang J, Wang C L, Chow L, Bechthold D, Dennis D T, Coolbaugh J C, Weiss E. Humoral and cellular responses in scrub typhus patients reflecting primary infection and reinfection with Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:532–540. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozeman F M, Elisberg B L. Serological diagnosis of scrub typhus by indirect immunofluorescence. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;112:568–573. doi: 10.3181/00379727-112-28107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown G W, Robinson D M, Huxsoll D L, Ng T S, Lim K J, Sannasey G. Scrub typhus: a common cause of illness in indigenous populations. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1976;70:444–448. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(76)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown G W, Saunders J P, Singh S, Huxsoll D L, Shirai A. Single dose deoxycycline therapy for scrub typhus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1978;72:412–416. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(78)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ching W-M, Wang H, Eamsila C, Kelly D, Dasch G A. Expression and refolding of truncated recombinant major outer membrane protein antigen (r56) of Orientia tsutsugamushi and its use in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:519–526. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.4.519-526.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi M, Seong S, Kang J, Kim Y, Huh M, Kim I. Homotypic and heterotypic antibody responses to a 56-kilodalton protein of Orientia tsutsugamushi. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6194–6197. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6194-6197.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuzzubbo A J, Chenthamarakshan V, Vadivelu J, Puthucheary S D, Rowland D, Devine P L. Evaluation of a new commercially available IgM and IgG immunochromatographic test for the diagnosis of melioidosis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1670–1671. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1670-1671.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasch G A, Halle S, Bourgeois A L. Sensitive microplate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibodies against the scrub typhus rickettsia, Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9:38–48. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.1.38-48.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasch G A, Strickman D, Watt G, Eamsila C. Measuring genetic variability in Orientia tsutsugamushi by PCR/RFLP analysis: a new approach to questions about its epidemiology, evolution, and ecology. In: Kazar J, editor. Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases, 5th International Symposium. Bratislava, Slovakia: Slovak Academy of Sciences; 1996. pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dohany A L, Shirai A, Robinson D M, Ram S, Huxsoll D L. Identification and antigenic typing of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in naturally infected chiggers (Acarina: Trombiculidae) by direct immunofluorescence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:1261–1264. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisemann C S, Osterman J V. Antigens of scrub typhus rickettsiae: separation by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and identification by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect Immun. 1981;32:525–533. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.525-533.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enatsu T, Urakami H, Tamura A. Phylogenetic analysis of Orientia tsutsugamushi strains based on the sequence homologies of 56-kDa type-specific antigen genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuya Y, Yoshida Y, Katayama T, Kawamori F, Yamamoto S, Ohashi N, Kamura A, Kawamura A., Jr Specific amplification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi DNA from clinical specimen by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2628–2630. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2628-2630.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanson B. Identification and partial characterization of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi major protein immunogens. Infect Immun. 1985;50:603–609. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.3.603-609.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horinouchi H, Murai K, Okayama A, Nagatomo Y, Tachibana N, Tsubouchi H. Genotypic identification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of DNA amplified by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:647–651. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. DHHS Publication (NIH) 86-23. Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly D J, Dasch G A, Chan T C, Ho T M. Detection and characterization of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) in infected Leptotrombidium (Leptotrombidium) fletcheri chiggers (Acari: Trombiculidae) with the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Entomol. 1994;31:691–699. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly D J, Marana D, Stover C, Oaks E, Carl M. Detection of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by gene amplification using polymerase chain reaction techniques. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;590:564–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly D J, Wong P W, Gan E, Lewis G E., Jr Comparative evaluation of the indirect immunoperoxidase test for the serodiagnosis of rickettsial disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:400–406. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim I-S, Seong S-Y, Woo S-G, Choi M-S, Chang W-H. High-level expression of a 56-kilodalton protein gene (bor56) of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi Boryong and its application to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:598–605. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.598-605.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim I-S, Seong S-Y, Woo S-G, Choi M-S, Chang W-H. Rapid diagnosis of scrub typhus by a passive hemagglutination assay using recombinant 56-kilodalton polypeptide. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2057–2060. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2057-2060.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Land M V, Ching W-M, Dasch G A, Zhang Z, Kelly D J, Graves S R, Devine P L. Evaluation of a commercially available recombinant-protein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibodies produced in scrub typhus rickettsial infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2701–2705. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2701-2705.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moree M F, Hanson B. Growth characteristics and proteins of plaque-purified strains of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3405–3415. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3405-3415.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murata M, Yoshida Y, Osono M, Ohashi N, Oyanagi M, Urakami H, Tamura A, Nogami S, Tanaka H, Kawamura A., Jr Production and characterization of monoclonal strain-specific antibodies against prototype strains of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30:599–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb02987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohashi N, Koyama Y, Urakami H, Fukuhara M, Tamura A, Kawamori F, Yamamoto S, Kasuya S, Yoshimura K. Demonstration of antigenic and genotypic variation in Orientia tsutsugamushi which were isolated in Japan, and their classification into type and subtype. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohashi N, Nashimoto H, Ikeda H, Tamura A. Diversity of immunodominant 56-kDa type-specific antigen (TSA) of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Sequence and comparative analyses of the genes encoding TSA homologues from four antigenic variants. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12728–12735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohashi N, Tamura A, Ohta M, Hayashi K. Purification and partial characterization of a type-specific antigen of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1427–1431. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1427-1431.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohashi N, Tamura A, Sakurai H, Suto T. Immunoblotting analysis of anti-rickettsial antibodies produced in patients of tsutsugamushi disease. Microbiol Immunol. 1988;32:1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1988.tb01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson D M, Brown G, Gan E, Huxsoll D L. Adaptation of a microimmunofluorescence test to the study of human Rickettsia tsutsugamushi antibody. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1976;25:900–905. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1976.25.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saunders J P, Brown G W, Shirai A, Huxsoll D L. The longevity of antibody to Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in patients with confirmed scrub typhus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1980;74:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(80)90254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugita Y, Nagatani T, Okuda K, Yoshida Y, Nakajima H. Diagnosis of typhus infection with Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:357–360. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-5-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suto T. Rapid serological diagnosis of tsutsugamushi disease employing the immuno-peroxidase reaction with cell cultured rickettsia. Clin Virol. 1980;8:425–429. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suwanabun N, Chouriyagune C, Eamsila C, Watcharapichat P, Dasch G A, Howard R S, Kelly D J. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in Thai scrub typhus patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:38–43. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura A, Ohashi N, Koyama Y, Fukuhara M, Kawamori F, Otsuru M, Wu P-F, Lin S-Y. Characterization of Orientia tsutsugamushi isolated in Taiwan by immunofluorescence and restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura A, Sakurami H, Takahashi K, Oyanagi M. Analysis of polypeptide composition and antigenic components of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting. Infect Immun. 1985;48:671–675. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.3.671-675.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weddle J R, Chan T C, Thompson K, Paxton H, Kelly D J, Dasch G, Strickman D. Effectiveness of a dot-blot immunoassay of anti-Rickettsia tsutsugamushi antibodies for serologic analysis of scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto S, Minamishima Y. Serodiagnosis of tsutsugamushi fever (scrub typhus) by the indirect immunoperoxidase technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1128–1132. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1128-1132.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]