Key Points

Question

Are patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) presenting to the emergency department (ED) more likely to have dermatology follow-up vs return to the ED for their disease, and what ED interventions and patient factors are associated with ED return vs dermatology follow-up?

Findings

In this cohort study of 20 269 patients with HS presenting to the ED for their HS or related proxy, ED return was high and dermatology outpatient follow-up was low. Opioid prescription at the index ED visit and Medicaid status were important factors associated with increased ED return and, in contrast, decreased dermatology outpatient follow-up for HS.

Meaning

These findings highlight critical gaps in care for patients with HS; cross-specialty education and interventions may be beneficial to connect high-risk patients with adequate follow-up care for their disease.

Abstract

Importance

Emergency department (ED) visitation is common for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), whereas dermatology outpatient care is low. The reasons underlying this differential follow-up have not been elucidated.

Objective

To assess the interventions and patient factors associated with ED return following an initial ED visit for HS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used data from the IBM® MarketScan® Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid databases (trademark symbols retained per database owner requirement). An HS cohort was formed from patients who had 2 or more claims for HS during the study period of 2010 to 2019 and with at least 1 ED visit for their HS or a defined proxy. Data were analyzed from November 2021 to May 2022.

Exposures

Factors analyzed included those associated with the ED visit and patient characteristics.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were return to the ED or dermatology outpatient follow-up for HS or related proxy within 30 or 180 days of index ED visit.

Results

This retrospective cohort study included 20 269 patients with HS (median [IQR] age, 32 [25-41] years; 16 804 [82.9%] female patients), of which 7455 (36.8%) had commercial insurance and 12 814 (63.2%) had Medicaid. A total of 9737 (48.0%) patients had incision and drainage performed at the index ED visit, 14 725 (72.6%) received an oral antibiotic prescription, and 9913 (48.9%) received an opioid medication prescription. A total of 3484 (17.2%) patients had at least 1 return ED visit for HS or proxy within 30 days, in contrast with 483 (2.4%) who had a dermatology visit (P < .001). Likewise, 6893 (34.0%) patients had a return ED visit for HS or proxy within 180 days, as opposed to 1374 (6.8%) with a dermatology visit (P < .001). Patients with Medicaid and patients who had an opioid prescribed were more likely to return to the ED for treatment of their disease (odds ratio [OR], 1.48; 95% CI, 1.38-1.58; and OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.39-1.58, respectively, within 180 days) and, conversely, less likely to have dermatology follow-up (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.14-0.18; and OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71-0.91, respectively, within 180 days).

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study suggests that many patients with HS frequent the ED for their disease but are not subsequently seen in the dermatology clinic for ongoing care. The findings in this study raise the opportunity for cross-specialty interventions that could be implemented to better connect patients with HS to longitudinal care.

This cohort study assesses the interventions and patient factors associated with emergency department return following an initial emergency department visit for hidradenitis suppurativa.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating skin disease that involves chronic follicular inflammation largely affecting the axilla, anogenital, and inframammary regions. The condition is characterized by painful nodules, abscesses, and sinus tracts that may result in unsightly scar formation. These lesions can have great psychosocial outcomes and lead to substantial decreases in quality of life.1,2,3,4,5 The condition has also been associated with a variety of serious medical comorbidities, including smoking, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, and diabetes,6,7,8 as well as substance use9,10 and psychiatric conditions.10,11,12,13,14 Prevalence varies depending on the population, but a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 studies estimated prevalence of approximately 0.4% globally.15

Many barriers to proper medical care for patients with HS exist. Patients are often misdiagnosed for years before receiving an HS diagnosis, with the average delay from the presentation of symptoms to diagnosis estimated to be 7 to 10 years.5,16,17 Patients frequently visit many different practitioners in various specialties before a definitive diagnosis is obtained, including general practitioners, surgeons, and gynecologists in addition to dermatologists, with dermatology being the most frequent specialty to finally make the diagnosis.16 Even once the diagnosis is made, patients with HS receive a large proportion of their care outside of the ambulatory dermatology setting, including frequently in high-cost emergency department (ED) and inpatient settings.5,18,19,20,21,22 Patients with HS have been shown to have increased use of these high-cost and acute care settings even when compared with other chronic inflammatory skin conditions such as psoriasis.21 By contrast, based on a 2017 population-based retrospective cohort study of 42 030 patients with HS, only 21.8% of patients had at least 1 ambulatory encounter with dermatology over a 3-year period.23

The overreliance on nonambulatory settings in HS patient care is critical to recognize for several reasons. This pattern results in increased costs to the health care system and the patient.20,21 Additionally, lack of consistent dermatology follow-up may result in delays in optimal care for these patients. There is increasing evidence that delays in diagnosis and initiation of biologic treatment, if needed, can be associated with worsened outcomes in HS, such as increased Hurley stage and decreased response to treatment.16,17,24 Interventions such as incision and drainage (I&D), short-term antibiotic prescription, and opioid prescription are common at ED encounters for HS,25 but these are temporizing remedies that do not contribute toward long-term medical control of the disease. For instance, recurrence of HS lesions after I&D occurs in up to 100% of cases.26 Opioid prescription in the ED may also be associated with ED return, as has been demonstrated for other conditions causing pain.27,28,29,30 Finally, HS disproportionately affects African American individuals31,32,33,34,35 and individuals of lower socioeconomic groups,36 such as those with Medicaid insurance.8 Thus, suboptimal patterns of health care utilization for HS could contribute to poorer outcomes for these patients of medically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Ultimately, although it has been demonstrated that patients with HS have high ED utilization for their disease and relatively low outpatient utilization, it is unclear what ED interventions and patient characteristics may be associated with these outcomes. The primary purpose of this cohort study was to investigate, in patients with HS who have an index ED visit for their disease, which interventions and patient characteristics were associated with ED return and dermatology follow-up within 30 and 180 days.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Multi-State Medicaid databases from 2010 to 2019. The MarketScan Research Databases contain inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy claims for more than 150 million individuals and include unique enrollee identifiers that allow for longitudinal analysis of health care utilization.37 Given the use of deidentified data, this study was considered exempt by the Washington University in St Louis Institutional Review Board. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Patient Selection

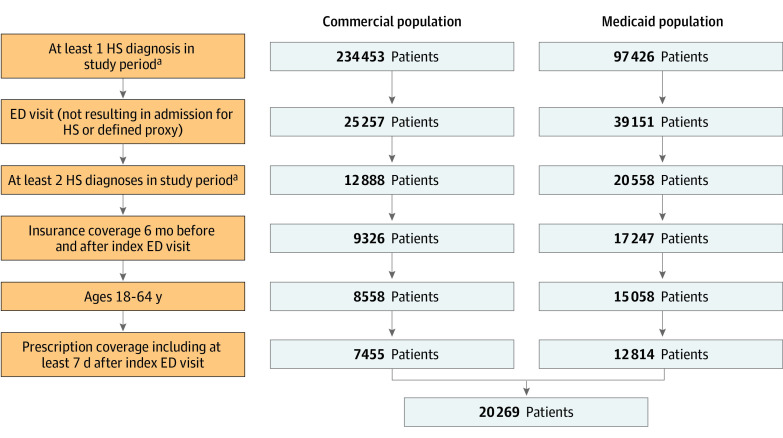

The selection of the HS study population is depicted in the Figure. The HS study population consisted of patients between 18 and 64 years old with 2 or more diagnosis claims of HS using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision codes and at least 1 ED visit (not resulting in admission) for their HS or a defined proxy between January 1, 2010, and July 4, 2019, in MarketScan Commercial Database and between January 1, 2011, and July 4, 2019, in the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database (allowing for 180 days after enrollment to assess outcomes up to December 31, 2019), based on institutional availability of data. The use of International Classification of Diseases coding to establish HS cohorts has previously been validated in prior studies.6,38 See variable definitions in eTable 1 in the Supplement. The index ED visit for HS was defined as the first ED visit not resulting in admission (treat and release) with a claim for HS or that of the HS proxy in a related diagnosis of folliculitis, cellulitis, abscess, carbuncle, or furuncle in locations typical for HS or unspecified site (eTable 1 in the Supplement), because studies have shown that nondermatology practitioners often misclassify HS as these diagnoses.16,39 We required insurance coverage 6 months before and after the index ED visit to document comorbidities and postindex outcomes. Prescription drug coverage was required for the 7 days after the index ED visit to document prescriptions associated with the encounter. Treatments were identified by the presence of a claim with a National Drug Code. Antibiotic and opioid prescriptions filled within 7 days of the index ED visit were documented. The antibiotics evaluated included the oral antibiotics that are most commonly used for HS (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The opioids evaluated were those most prescribed in an ED setting40 (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Procedures involving I&D were evaluated by Current Procedural Terminology, Fourth Edition, codes. Additional information was recorded on patient characteristics, including age, sex, and comorbid conditions consisting of selected important Elixhauser comorbidities and additional conditions relevant to the HS population. Comorbidities were identified in the 6 months before index ED visit based primarily on the Elixhauser classification,41,42,43 requiring coding of at least 1 inpatient facility hospitalization and/or at least 2 practitioner or outpatient facility (excluding diagnostic) claims spaced at least 30 days apart44 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Only 1 outpatient claim was required to identify obesity, weight loss, and tobacco use because a diagnostic workup is not required for those conditions44 (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Patients were considered to live in an urban area if they were coded as residing in a metropolitan statistical area. The variables of US region, race and ethnicity, and metropolitan statistical area were not included in statistical analyses because geography was only available for commercially insured patients and race and ethnicity were only available for Medicaid patients. Race and ethnicity were included as relevant metrics because of the higher prevalence of HS in African American individuals, and race and ethnicity were self-reported.

Figure. Selection of Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) Patient Population by Insurance Status.

ED indicates emergency department.

aBased on institutional availability, data spanning 2010 to 2019 from the MarketScan Commercial Database and from 2011 to 2019 from the MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database.

Follow-up was defined as an outpatient or ED visit specifically with HS or proxy as a diagnosis. The primary outcomes of interest were ED return and dermatology visit for HS or proxy within 30 days and 180 days. Dermatology outpatient follow-up was defined by the “provider type” variable (STDPROV) with value of 215, indicating dermatology. Thirty days was selected as a time frame representing closer follow-up, though 180 days was chosen as a reasonable time frame during which a patient should be able to access a dermatologist given prolonged wait times for dermatology in many areas.

Statistical Analyses

To compare categorical variables between the commercial and Medicaid populations, χ2 tests were used. The associations between interventions at the index ED visit and the odds of ED return or dermatology follow-up for HS at 30 days and 180 days were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression. Covariates used in all regression models were selected a priori based on clinical relevance and included age, sex, and comorbidities, and were checked for collinearity. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were generated from the multivariable analyses. Planned subgroup analyses including only the patients with an HS diagnosis code at index ED visit (and not the proxy) were also performed. Statistical tests were 2-sided and significant at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Data were analyzed during November 2021 to May 2022.

Results

Patient Population

The study included 20 269 patients with HS with an index ED visit, of which 7455 (36.8%) had commercial insurance and 12 814 (63.2%) had Medicaid. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1 by insurance status (see eTable 3 in the Supplement for baseline characteristics for those patients with HS code at index visit vs proxy). Patients were predominantly female (16 804 [82.9%] patients) and of younger age (12 261 [60.5%] patients between 18 and 34 years). In the Medicaid population, 6661 (52.0%) patients were Black and 4635 (36.2%) were White (race and ethnicity not available in the Commercial Database). There was a high medical comorbidity burden in both populations, including 4552 (22.5%) patients overall with obesity, 2403 (11.9%) with diabetes, and 334 (1.6%) with inflammatory bowel disease.

Table 1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS) Population by Insurance Status.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | Medicaid | Overall | ||

| Age range, y | ||||

| 18-24 | 1869 (25.1) | 2910 (22.7) | 4779 (23.6) | <.001 |

| 25-34 | 2153 (28.9) | 5329 (41.6) | 7482 (36.9) | |

| 35-44 | 1754 (23.5) | 2898 (22.6) | 4652 (23.0) | |

| 45-54 | 1143 (15.3) | 1236 (9.6) | 2379 (11.7) | |

| 55-64 | 536 (7.2) | 441 (3.4) | 977 (4.8) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 5667 (76.0) | 11 137 (86.9) | 16 804 (82.9) | <.001 |

| Male | 1788 (24.0) | 1677 (13.1) | 3465 (17.1) | |

| Race and ethnicitya | ||||

| Black | NA | 6661 (52.0) | NA | NA |

| Hispanic | NA | 199 (1.6) | NA | |

| White | NA | 4635 (36.2) | NA | |

| Otherb | NA | 764 (6.0) | NA | |

| Unknown | NA | 555 (4.3) | NA | |

| Region | ||||

| North Central | 1730 (23.2) | NA | NA | NA |

| Northeast | 1130 (15.2) | NA | NA | |

| South | 3841 (51.5) | NA | NA | |

| West | 672 (9.0) | NA | NA | |

| Unknown | 82 (1.1) | NA | NA | |

| MSA | ||||

| Rural | 858 (11.5) | NA | NA | NA |

| Urban | 6325 (84.8) | NA | NA | |

| Unknown | 272 (3.6) | NA | NA | |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| No | 5875 (78.8) | 6314 (49.3) | 12 189 (60.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | 1580 (21.2) | 6500 (50.7) | 8080 (39.9) | |

| Alcohol use disorder | ||||

| No | 7383 (99.0) | 12 494 (97.5) | 19 877 (98.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | 72 (1.0) | 320 (2.5) | 392 (1.9) | |

| Drug abuse | ||||

| No | 7334 (98.4) | 11 655 (91.0) | 18 989 (93.7) | <.001 |

| Yes | 121 (1.6) | 1159 (9.0) | 1280 (6.3) | |

| Obesity | ||||

| No | 6131 (82.2) | 9586 (74.8) | 15 717 (77.5) | <.001 |

| Yes | 1324 (17.8) | 3228 (25.2) | 4552 (22.5) | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 6709 (90.0) | 11 157 (87.1) | 17 866 (88.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | 746 (10.0) | 1657 (12.9) | 2403 (11.9) | |

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 6505 (87.3) | 10 477 (81.8) | 16 982 (83.8) | <.001 |

| Yes | 950 (12.7) | 2337 (18.2) | 3287 (16.2) | |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||

| No | 7414 (99.5) | 12 685 (99.0) | 20 099 (99.2) | <.001 |

| Yes | 41 (0.5) | 129 (1.0) | 170 (0.8) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||

| No | 7400 (99.3) | 12 720 (99.3) | 20 120 (99.3) | .97 |

| Yes | 55 (0.7) | 94 (0.7) | 149 (0.7) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | ||||

| No | 7103 (95.3) | 11 308 (88.2) | 18 411 (90.8) | <.001 |

| Yes | 352 (4.7) | 1506 (11.8) | 1858 (9.2) | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | ||||

| No | 7301 (97.9) | 12 634 (98.6) | 19 935 (98.4) | <.001 |

| Yes | 154 (2.1) | 180 (1.4) | 334 (1.6) | |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||

| No | 6726 (90.2) | 10 381 (81.0) | 17 107 (84.4) | <.001 |

| Yes | 729 (9.8) | 2433 (19.0) | 3162 (15.6) | |

| Bipolar disorders | ||||

| No | 7219 (96.8) | 11 367 (88.7) | 18 586 (91.7) | <.001 |

| Yes | 236 (3.2) | 1447 (11.3) | 1683 (8.3) | |

| Depressive disorders | ||||

| No | 7192 (96.5) | 11 712 (91.4) | 18 904 (93.3) | <.001 |

| Yes | 263 (3.5) | 1102 (8.6) | 1365 (6.7) | |

| Psychoses | ||||

| No | 7182 (96.3) | 11 469 (89.5) | 18 651 (92.0) | <.001 |

| Yes | 273 (3.7) | 1345 (10.5) | 1618 (8.0) | |

Abbreviation: MSA, metropolitan statistical area; NA, not applicable.

Race is not a factor in reimbursement and therefore not collected by private insurers.

MarketScan classified White, Black, Hispanic and Other. Because it is self-reported, this includes every other possible category a state could collect, which is variable.

Outcomes

Interventions associated with the index ED visit are summarized in eTable 4 in the Supplement by insurance status. A total of 9737 (48.0%) patients had I&D performed at the index ED visit, with greater rates in the commercial group (51.0% for commercial vs 46.3% for Medicaid; P < .001). A total of 14 725 (72.6%) patients filled oral antibiotic prescriptions within 7 days of index ED visit (72.1% for commercial vs 73.0% for Medicaid; P = .18), with no statistically significant differences between the commercial and Medicaid populations. A total of 9913 (48.9%) patients filled oral opioid pain medications within 7 days of index ED visit, with greater frequency in the Medicaid population (46.5% for commercial vs 50.3% for Medicaid; P < .001).

Return to the ED and dermatology outpatient follow-up for HS or proxy are summarized in Table 2 by insurance status. A total of 3484 (17.2%) patients had at least 1 return ED visit for HS or proxy within 30 days (15.7% for commercial vs 18.1% for Medicaid; P < .001), as opposed to the 483 (2.4%) who had a dermatology outpatient visit for HS or proxy within 30 days (5.3% for commercial vs 0.7% for Medicaid; P < .001). Similarly, 6893 (34.0%) patients had at least 1 return ED visit for HS or proxy within 180 days after the index ED visit (27.2% for commercial vs 38.0% for Medicaid; P < .001), though only 1374 (6.8%) had a dermatology outpatient visit for HS or proxy within 180 days (14.1% for commercial vs 2.5% for Medicaid; P < .001).

Table 2. Emergency Department (ED) Return and Dermatology Outpatient Follow-up Within 30 and 180 Days.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial insurance | Medicaid insurance | Overall | ||

| ED visit for HS or proxy within 30 d | ||||

| No | 6288 (84.3) | 10 497 (81.9) | 16 785 (82.8) | <.001 |

| Yes | 1167 (15.7) | 2317 (18.1) | 3484 (17.2) | |

| Dermatology office visit for HS or proxy within 30 d | ||||

| No | 7059 (94.7) | 12 727 (99.3) | 19 786 (97.6) | <.001 |

| Yes | 396 (5.3) | 87 (0.7) | 483 (2.4) | |

| ED visit for HS or proxy within 180 d | ||||

| No | 5427 (72.8) | 7949 (62.0) | 13 376 (66.0) | <.001 |

| Yes | 2028 (27.2) | 4865 (38.0) | 6893 (34.0) | |

| Dermatology office visit for HS or proxy within 180 d | ||||

| No | 6404 (85.9) | 12 491 (97.5) | 18 895 (93.2) | <.001 |

| Yes | 1051 (14.1) | 323 (2.5) | 1374 (6.8) | |

Abbreviation: HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

To investigate the association of insurance status and index ED visit interventions with odds of follow-up visits for HS, multivariable logistic regression adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities was performed (Table 3; full table including all variables in eTable 5 in the Supplement). Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that I&D performed at index ED visit was associated with an increased odds of ED follow-up within 30 days (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.10-1.28; P < .001) and 180 days (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.13-1.28; P < .001) compared with patients who did not have an I&D procedure. Having an I&D procedure was also associated with an increased odds of dermatology outpatient follow-up within 30 days (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.02-1.48; P = .03) and 180 days (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.34; P = .003) compared with those without.

Table 3. Odds Ratios (ORs) of Emergency Department (ED) Return and Dermatology Outpatient Follow-up Within 30 and 180 Days, Adjusted for Demographic Factors and Comorbiditiesa,b.

| Characteristic | OR of ED return for HS or proxy within 30 d (95% CI) | P value | OR of dermatology outpatient visit for HS or proxy within 30 d (95% CI) | P value | OR of ED return for HS or proxy within 180 d (95% CI) | P value | OR of dermatology outpatient visit for HS or proxy within 180 d (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid insurance | 1.12 (1.03-1.22) | .009 | 0.12 (0.09-0.15) | <.001 | 1.48 (1.38-1.58) | <.001 | 0.16 (0.14-0.18) | <.001 |

| Intervention at index ED visit | ||||||||

| Incision and drainage | 1.19 (1.10-1.28) | <.001 | 1.23 (1.02-1.48) | .03 | 1.20 (1.13-1.28) | <.001 | 1.19 (1.06-1.34) | .003 |

| Opioid prescription | 1.67 (1.54-1.80) | <.001 | 0.78 (0.64-0.95) | .01 | 1.48 (1.39-1.58) | <.001 | 0.81 (0.71-0.91) | <.001 |

| Antibiotic prescription | 0.97 (0.89-1.06) | .50 | 1.28 (1.02-1.60) | .03 | 0.84 (0.78-0.90) | <.001 | 1.06 (0.93-1.22) | .37 |

Abbreviation: HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Model adjusted for the following variables: age category and sex as well as comorbidities of tobacco use, alcohol use disorder, drug abuse, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, inflammatory bowel disease, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorders, depressive disorders, and psychoses.

Odds ratios and P values based on multivariable logistic regression adjusting for all variables listed.

Oral opioid pain medication prescription (filled within 7 days of index visit) was associated with statistically significant increased odds of ED follow-up within 30 days (OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.54-1.80; P < .001) and 180 days (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.39-1.58; P < .001). In contrast, opioid pain medication prescription was associated with statistically significant decreased odds of dermatology follow-up within 30 days (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64-0.95; P = .01) and 180 days (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71-0.91]; P < .001).

Oral antibiotic prescription (filled within 7 days of index visit) was associated with decreased odds of ED return within 180 days (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.78-0.90; P < .001) but no statistically significant difference within 30 days (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.89-1.06; P = .50). It was also associated with increased odds of dermatology follow-up within 30 days (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.02-1.60; P = .03), but not within 180 days (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.93-1.22; P = .37).

Medicaid patients had increased odds of ED return within 30 days (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.03-1.22; P = .009) and 180 days (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.38-1.58; P < .001). In contrast, Medicaid insurance status was associated with decreased odds of outpatient dermatology follow-up within 30 days (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.09-0.15; P < .001) and 180 days (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.14-0.18; P < .001).

Subgroup Analyses

Given a proxy was also used to identify index ED visits in addition to the HS diagnosis code, subgroup analyses were performed including only the smaller population of 2757 (13.6%) patients who had an HS diagnosis code at the index ED visit as opposed to with the proxy included (eTable 6 in the Supplement). These analyses revealed similar overall trends to the main conclusions. Medicaid status remained associated with statistically significant increased ED return and, conversely, decreased dermatology follow-up within both 30 and 180 days. Opioid prescription also remained statistically significantly associated with increased ED follow-up within 30 and 180 days and decreased dermatology follow-up within 180 days, with no statistically significant difference in dermatology follow-up within 30 days. Antibiotic prescription was associated with decreased ED return within 30 and 180 days and no statistically significant differences in dermatology follow-up. Having an I&D procedure was not associated with statistically significant differences in ED or dermatology follow-up within either 30 or 180 days.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of 20 269 patients with HS seen in the ED setting, a mere 483 (2.4%) and 1374 (6.8%) were seen in dermatology follow-up within 30 and 180 days, respectively. In contrast, 3484 (17.2%) and 6893 (34.0%) were seen in the ED again within 30 and 180 days, respectively. Factors associated with decreased dermatologic follow-up included Medicaid insurance status and prescription of opioid pain medications at the index ED visit. Previous studies have shown high inpatient and ED utilization for their disease in patients with HS. Importantly, this study highlights a critical gap in care for patients with HS because a majority of these patients who present to the ED do not make it into the ambulatory dermatology setting for follow-up. Ideally, ED returns should be infrequent and dermatology follow-up should be high. However, these findings indicate that the situation was closer to the reverse.

Notably, Medicaid patients had statistically significant increased odds of ED return for their HS and lower odds of dermatology follow-up for their disease, highlighting an important disparity in care. In patients with commercial insurance, 14.1% had dermatology follow-up within 180 days, compared with only 2.5% for patients with Medicaid. This difference in follow-up may be multifactorial. For one, many dermatology offices may not accept Medicaid insurance, limiting patient access to dermatology care. A recent study found that merely 17% of nonacademic adult medical dermatology practices accepted Medicaid insurance.45 Comparatively, another study demonstrated that 75.7% of academic dermatology institution sites nationwide accepted Medicaid insurance.46 Although this latter percentage is much higher, it does reveal many Medicaid patients cannot find a home for treatment of their condition at academic institutions either. Additionally, Medicaid insurance by nature represents patients of socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. Medicaid is the main insurer for low-income and disabled Americans and represents a disproportionate proportion of racial and ethnic minority groups, such as African American and Hispanic patients.47 Moreover, rural populations have a higher rate of Medicaid insurance status than urban populations, and studies have demonstrated a substantial disparity between urban and rural areas with regard to dermatologist density that continues to increase.48,49 Thus, the differential follow-up pattern revealed in this study for patients with HS reflects another area in which there is a disparity in care for patients of underprivileged backgrounds.

Furthermore, this study also showed that opioid pain medication prescription was associated with higher odds of ED follow-up and lower odds of dermatology follow-up. Opioid medications, although they offer temporary and often important relief, do not change the HS disease course. Although pain management is certainly an essential component of HS care, this study demonstrated the need for sufficient ongoing medical care to accompany this. Importantly, the overall rates of opioid prescriptions from the ED have decreased in recent years, likely associated with increased awareness of the opioid epidemic.50

Taken as a whole, this study highlights potential areas of action to improve care for patients with HS. Cross-specialty interventions among all the different specialties that care for patients with HS—such as dermatology, ED, and surgical practitioners—would likely be beneficial with regard to improving medical care for these patients and connecting patients to long-term outpatient dermatology care. Additionally, specific plans can be made to target patients who are at higher risk for ED return. Further research, such as qualitative studies, could also be performed to better understand the reasons for these differential follow-up patterns.

Limitations

Limitations of this study included the small effect sizes for some of the associations observed, because the results may have been statistically significant but not clinically significant. Further limitations included those that are inherent to studies using large administrative data sets. One limitation was the lack of granularity provided by large administrative databases that prevented us from identifying certain details regarding patient and treatment information. For one, although the differences between the commercial and Medicaid populations allowed us to have some sense of socioeconomic status, the data set did not allow for more precise socioeconomic data. Additionally, there was the potential for undercoding and misclassification bias from errors in coding. Specifically, dermatology follow-up visits could be undercoded given the practitioner type may be coded generically such as “medical doctor, not elsewhere classified” instead of with a particular specialty. The restriction of the patient population to those with continuous insurance coverage over a certain period, though standard in administrative data research, also may have prevented the inclusion of some vulnerable patients. Finally, given that the MarketScan Research Databases are based on a large convenience sample of insurance claims, these findings may not be generalizable to those who are uninsured or with different types of health insurance.

Conclusions

In this retrospective cohort study of a large national administrative data set, patients with HS presenting to the ED for their disease exhibited high rates of ED return with low rates of dermatology follow-up after an initial ED visit. Factors such as opioid prescription after ED visit and Medicaid status were associated with increased odds of ED return but lower odds of dermatology follow-up. Future investigations are needed to understand the reasons underlying these patterns and to aid with interventions to address these critical gaps in care.

eTable 1. ICD-9, ICD-10, and CPT-4 codes for variables

eTable 2. Antibiotic and opioid medications

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of patient population of patients with HS diagnosis code at index visit vs. proxy

eTable 4. Interventions at index ED visit

eTable 5. Odds ratios of ED return and dermatology outpatient follow-up within 180 days and 30 days

eTable 6. Odds ratios of ED return and dermatology outpatient follow-up within 180 days and 30 days for HS population including only those with an HS diagnosis (not proxy) at index ED visit

References

- 1.Gooderham M, Papp K. The psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5)(suppl 1):S19-S22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esmann S, Jemec GB. Psychosocial impact of hidradenitis suppurativa: a qualitative study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91(3):328-332. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Psychophysical aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(3):264-268. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider-Burrus S, Tsaousi A, Barbus S, et al. Features associated with quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa patients. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:676241. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.676241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg A, Neuren E, Cha D, et al. Evaluating patients’ unmet needs in hidradenitis suppurativa: results from the Global Survey Of Impact and Healthcare Needs (VOICE) project. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):366-376. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shlyankevich J, Chen AJ, Kim GE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1144-1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohorst JJ, Kimball AB, Davis MD. Systemic associations of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5)(suppl 1):S27-S35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marvel J, Vlahiotis A, Sainski-Nguyen A, Willson T, Kimball A. Disease burden and cost of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective examination of US administrative claims data. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e030579. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, Strunk A, Merson J. Opioid, alcohol, and cannabis misuse among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):495-500.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel KR, Rastogi S, Singam V, Lee HH, Amin AZ, Silverberg JI. Association between hidradenitis suppurativa and hospitalization for psychiatric disorders: a cross-sectional analysis of the National Inpatient Sample. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(2):275-281. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jalenques I, Ciortianu L, Pereira B, D’Incan M, Lauron S, Rondepierre F. The prevalence and odds of anxiety and depression in children and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):542-553. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huilaja L, Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, Tasanen K. Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have a high psychiatric disease burden: a Finnish nationwide registry study. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(1):46-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, Halevy S, Vinker S, Cohen AD. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(2):371-376. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machado MO, Stergiopoulos V, Maes M, et al. Depression and anxiety in adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(8):939-945. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jfri A, Nassim D, O’Brien E, Gulliver W, Nikolakis G, Zouboulis CC. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(8):924-931. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokolakis G, Wolk K, Schneider-Burrus S, et al. Delayed diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa and its effect on patients and healthcare system. Dermatology. 2020;236(5):421-430. doi: 10.1159/000508787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunte DM, Boer J, Stratigos A, et al. Diagnostic delay in hidradenitis suppurativa is a global problem. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1546-1549. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos JV, Lisboa C, Lanna C, Costa-Pereira A, Freitas A. Hospitalisations with hidradenitis suppurativa: an increasing problem that deserves closer attention. Dermatology. 2016;232(5):613-618. doi: 10.1159/000448515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai N, Shah P. High burden of hospital resource utilization in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in England: a retrospective cohort study using hospital episode statistics. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):1048-1055. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirby JS, Miller JJ, Adams DR, Leslie D. Health care utilization patterns and costs for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(9):937-944. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):609-614. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frings VG, Schöffski O, Goebeler M, Presser D. Economic analysis of the costs associated with hidradenitis suppurativa at a German university hospital. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg A, Lavian J, Strunk A. Low utilization of the dermatology ambulatory encounter among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based retrospective cohort analysis in the USA. Dermatology. 2017;233(5):396-398. doi: 10.1159/000480379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marzano AV, Genovese G, Casazza G, et al. Evidence for a ‘window of opportunity’ in hidradenitis suppurativa treated with adalimumab: a retrospective, real-life multicentre cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(1):133-140. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor MT, Orenstein LAV, Barbieri JS. Pain severity and management of hidradenitis suppurativa at us emergency department visits. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(1):115-117. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritz JP, Runkel N, Haier J, Buhr HJ. Extent of surgery and recurrence rate of hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13(4):164-168. doi: 10.1007/s003840050159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginsberg Z, Ghaith S, Pollock JR, et al. Relationship between pain management modality and return rates for lower back pain in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2021;61(1):49-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Megalla M, Ogedegbe C, Sanders AM, et al. Factors associated with repeat emergency department visits for low back pain. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e21906. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yau FF, Yang Y, Cheng CY, Li CJ, Wang SH, Chiu IM. Risk factors for early return visits to the emergency department in patients presenting with nonspecific abdominal pain and the use of computed tomography scan. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(11):1470. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9111470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masonbrink A, Richardson T, Catley D, et al. Opioid use to treat migraine headaches in hospitalized children and adolescents. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(5):401-407. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Udechukwu NS, Fleischer AB Jr. Higher risk of care for hidradenitis suppurativa in African American and non-Hispanic patients in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2017;109(1):44-48. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vlassova N, Kuhn D, Okoye GA. Hidradenitis suppurativa disproportionately affects African Americans: a single-center retrospective analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(8):990-991. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaidya T, Vangipuram R, Alikhan A. Examining the race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa at a large academic center; results from a retrospective chart review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(6):13030/qt9xc0n0z1. doi: 10.5070/D3236035391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, Strunk A, Alloo A. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(1):118-122. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edigin E, Kaul S, Eseaton PO, Albrecht J. Racial and ethnic distribution of patients hospitalized with hidradenitis suppurativa, 2008-2018. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(9):1125-1127. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wertenteil S, Strunk A, Garg A. Association of low socioeconomic status with hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(9):1086-1088. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.IBM . IBM MarketScan Research Databases. Accessed April 15, 2022. https://www.ibm.com/products/marketscan-research-databases/databases

- 38.Strunk A, Midura M, Papagermanos V, Alloo A, Garg A. Validation of a case-finding algorithm for hidradenitis suppurativa using administrative coding from a clinical database. Dermatology. 2017;233(1):53-57. doi: 10.1159/000468148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hallock KK, Mizerak MR, Dempsey A, Maczuga S, Kirby JS. Differences between children and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(9):1095-1101. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanuck J, Lee JB, Saadat S, et al. Opioid prescription patterns for discharged patients from the emergency department. Pain Res Manag. 2021;2021:4980170. doi: 10.1155/2021/4980170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project clinical classifications software for ICD-9-CM. Accessed December 17, 2021. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

- 43.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Elixhauser comorbidity software, version 3.7. Accessed December 17, 2021. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp

- 44.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258-1267. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(2):181-188. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams JC, Maxey AE, Wei ML, Amerson EH. A cross-sectional analysis of Medicaid acceptance among US dermatology residency training programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(2):453-455. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guth M, Artiga S. Medicaid and racial health equity. Kaiser Family Foundation. March 17, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-and-racial-health-equity/

- 48.Feng H, Berk-Krauss J, Feng PW, Stein JA. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1265-1271. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glazer AM, Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution and density of US dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(4):322-325. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gleber R, Vilke GM, Castillo EM, Brennan J, Oyama L, Coyne CJ. Trends in emergency physician opioid prescribing practices during the United States opioid crisis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(4):735-740. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD-9, ICD-10, and CPT-4 codes for variables

eTable 2. Antibiotic and opioid medications

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of patient population of patients with HS diagnosis code at index visit vs. proxy

eTable 4. Interventions at index ED visit

eTable 5. Odds ratios of ED return and dermatology outpatient follow-up within 180 days and 30 days

eTable 6. Odds ratios of ED return and dermatology outpatient follow-up within 180 days and 30 days for HS population including only those with an HS diagnosis (not proxy) at index ED visit