Abstract

Several cutaneous manifestations in patients undergoing COVID-19 vaccination have been described in the literature. Herein, we presented a case of new-onset vitiligo that occurred after the second dose of the Comirnaty vaccine. An updated literature search revealed the occurrence of a total of 16 cases, including new-onset or worsening of preexisting vitiligo. Given the autoimmune pathogenesis of the disease, we reviewed and discussed the potential role of the vaccine prophylaxis as a trigger for the development of such hypopigmented skin lesions.

Keywords: autoimmunity, autoimmune diseases, vitiligo, vaccine, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccination campaign, several skin adverse reactions after the dose administrations have been reported in the medical literature [1,2,3]. They mainly consist of delayed inflammatory reactions at the injection site, urticaria, chilblain-like lesions, and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions [2,4]. However, cutaneous and extracutaneous autoimmune diseases (ADs) have been documented [1]. Herein, we presented a case report of a patient who developed new-onset vitiligo after receiving the second dose of the Comirnaty vaccine.

Although a clear etiopathogenetic link between SARS-CoV-2 infection with related prophylaxis and this typical cutaneous autoimmune disease has not been definitely demonstrated, their association emerged during the pandemic and postpandemic era and seems to be not accidental. With the purpose of reviewing the pertinent literature, we checked the PubMed (https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed, accessed on 15 August 2022), Scopus, and Web of Science databases using the string “Vitiligo” [All Fields] AND “COVID-19” [All Fields] without time limits. According to the search results and their critical analysis, we discussed possible hypotheses that may underlie such unexpected events.

2. Case Presentation

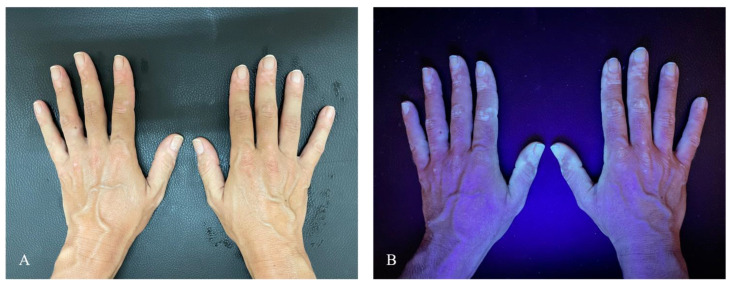

A 35-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the dermatology clinic complaining of sudden depigmentation of the hands. The patient reported the occurrence of discoloration after receiving the second dose of the Comirnaty vaccine. Physical examination revealed multiple depigmented patches on bilateral dorsal hands (Figure 1A). The patches were consistent with vitiligo, and evaluation under Wood’s light revealed the characteristic white fluorescence (Figure 1B). No other body areas were involved. Blood test including thyrotropin was within the normal range. Antithyroid peroxidase and antithyroglobulin antibodies were negative. Familial and personal medical history was unremarkable for other cutaneous or extracutaneous autoimmune diseases. Moreover, no history of systemic or topical drugs reported to be linked with secondary vitiligo was reported. COVID-19 vaccination was considered as the potential culprit for the skin changes given the lack of other potential causative factors and the temporal link between vaccination and the lesions’ outbreak. She was treated with topical khellin twice daily. The outcome at 3 months was not available because the patient was lost to follow-up. A written consent to treatment and image recording for academic purposes was obtained.

Figure 1.

(A) Multiple depigmented patches on bilateral dorsal hands. (B) Evidence of hypopigmented areas under Wood’s light.

3. Review of Literature

To the best of our knowledge, only 16 additional cases linking vitiligo to COVID-19 have been reported in the literature and are summarized in Table 1, including the ones occurring as a new onset and recrudescence after vaccination and manifestations of the disease in the course of COVID-19 infection [1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Our search revealed 7 male patients affected versus 11 female patients whose age at presentation ranged from 13 to 86 years (mean age 50.625 ± 17.421). Out of 16, 2 (one man and one woman) had preexisting vitiligo, while the rest of the patients newly presented hypopigmented lesions after vaccination. The onset of the condition generally occurred a few days (maximum 1 week) after the dose administration: in seven cases, lesions abrupted after the first dose; in four cases after the second dose; and in three cases, they were repetitive after the first and second doses. In two cases, vitiligo appeared after the COVID-19 disease. Out of fourteen vaccinated patients, nine presented the skin condition after Comirnaty administration, whereas three after Moderna and only two after AstraZeneca. The three cases characterized by the recurrence of lesions at the second dose administration occurred with each of the three different types of vaccination. With regard to the clinical manifestations, vitiligo presented with the classical topography except for one case, in which hypopigmentation occurred at the site of injection as the isomorphic response. According to familial anamnesis, only two patients reported a history of the skin disease. Curiously, these patients were not positive for preexisting lesions. Manifestations remained generally stable, limited to the observation time, with poor or no response to the dermatological treatments and with only four cases slightly improving with calcineurin inhibitors and/or UV phototherapy plus topical or oral steroids. In one case, marked by preexisting lesions, worsening was noted. Autoimmunity- and autoinflammatory-based comorbidities, including ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, Hashimoto’ thyroiditis, type II diabetes mellitus, and ankylosing spondylitis, were present in four patients, whereas hypothyroidism and slight positivity of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) were recorded in additional two patients. The unique case of Koebnerization at the inoculation site occurred in a patient having psoriasis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and type II diabetes.

Table 1.

Synoptical review of cases of vitiligo after COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccination reported in medical literature.

| Authors, Reference Number, and Year | Type of Study | Sex/Age (Year) | Country of Origin | Clinical Course | Onset after Vaccination | Localization | Vitiligo Familial History | Comorbidities | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aktas H [5], 2021 | Case report | M/58 | Turkey | New onset after Pfizer- BioNTech first dose | 1 week | Face | No | Ulcerative colitis | Topical tacrolimus | 1 month: stable |

| Kaminetsky J [6], 2021 | Case report | W/61 | USA | New onset after Moderna mRNA-1273 first and second dose | Several days after first dose, progressing after second dose | Anterior neck after first dose, spreading to face, neck, chest, abdomen after second dose | No | None | Topical calcineurin inhibitor, phototherapy | Not reported |

| Ciccarese G [1], 2021 | Case report | W/33 | Italy | New onset after Pfizer- BioNTech first dose | 1 week | Trunk, neck, back | Yes (father) | None, ANA + (1:160) nucleolar pattern | Antioxidants systemic, heliotherapy | 1 month: stable |

| Herzum A [7], 2021 | Case report | W/45 | Italy | New onset after COVID-19 | 2 weeks | Limbs, face, trunk | No | None | Phototherapy | 1 month: stable |

| Lopez Riquelme I [8], 2022 | Case report | W/60 | Spain | New onset after AstraZeneca first dose | 3 days | Face and arms | Not reported | None | Topical tacrolimus | Not reported |

| Flores-Terry M [9], 2022 | Case report | W/39 | Spain | New onset after Pfizer- BioNTech second dose | 1 week | Face | No | None | Not reported | Not reported |

| Militello M [10], 2022 | Case report | W/67 | USA | New onset after Moderna mRNA-1273 first dose | 2 weeks | Dorsal hands | Not reported | None | Topical steroids | Not reported |

| Nicolaidou E [11], 2022 | Case report | M/69 | Greece | New onset after Pfizer- BioNTech first and second dose | Few days after first dose, progressing after second dose | Face, abdomen, back, upper and lower limbs | No | None | Phototherapy | 2 months: partial improvement |

| Singh R [12], 2022 | Case report | W/43 | USA | New onset after Moderna mRNA-1273 first dose | 3 weeks | Left upper arm (at the site of injection), face, scalp, chest | Not reported | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, type II diabetes, psoriasis | Topical steroids and topical tacrolimus | Not reported |

| Schmidt A [13], 2022 | Case report | W/52 | USA | New onset after COVID-19 | 4 weeks | Neck, face, trunk | No | Hypothyroidism | Topical tacrolimus, topical and oral steroids | 7 months: partial improvement |

| Bukhari A [14], 2022 | Case report | W/13 | Saudi Arabia | New onset after Pfizer- BioNTech first dose | 2 weeks | Upper and lower limbs | Yes (father and paternal uncle) | No | Topical calcineurin inhibitor, topical steroid, and localized phototherapy | 3 months: partial improvement |

| Uğurer E [15], 2022 | Case report | M/47 | Turkey | New onset after Pfizer- BioNTech first dose | 1 week | Bilateral axilla and forearm flexor surfaces | Not reported | Ankylosing spondylitis | Topical pimecrolimus | 1 month: partial improvement |

| Koç Yıldırım S [16], 2022 | Case report | M/49 | Turkey | New onset after Pfizer- BioNTech second dose | 2 weeks | Face | No | No | Topical tacrolimus | Not reported |

| Gamonal S [17], 2022 | Case report | M/86 | Brazil | New onset of vitiligo and lichen planus after AstraZeneca first and second dose | 1 week after first dose, progressing after second dose | Upper and lower limbs, trunk, and buttocks | Not reported | Not reported | Topical steroid | Not reported |

| Caroppo F [18], 2022 | Case report | M/66 | Italy | Preexisting vitiligo worsened after Pfizer-BioNTech second dose | 2 weeks | Upper and lower limbs, face, trunk, genital area | No | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | Oral and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus | Not reported |

| Okan G [19], 2021 | Case report | M/22 | Turkey | Preexisting vitiligo worsened after Pfizer-BioNTech second dose | 2 weeks | Face | No | None | Topical tacrolimus | 2 months: no response |

Legend: W: woman, M: man.

4. Discussion

Vitiligo is a common autoimmune skin disease involving approximately 0.5–2% of the world population [20], ranging from 0.38% in the Danish peninsula and 0.49% in the USA to 1.9% in China and 2.28% in a remote area of Romania, with no differences between adults and children [21].

The onset of vitiligo often occurs in younger individuals and progresses with time, resulting in a disfiguring disease [22]. However, the clinical course remains generally unpredictable in both segmental and nonsegmental form [23]. The characteristic milky-white macules derive from the selective destruction of melanocytes in the skin or hair or both [22]. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of vitiligo offer a better understanding of the course of this autoimmune disease. On the background of genetic susceptibility, the presence of an intrinsic anomaly of melanocytes makes them more sensitive to oxidative damage, leading to a greater expression of proinflammatory proteins such as Heat Shock Protein 70 kilodaltons (HSP70), which plays a pivotal role in the promotion of specific immune responses assisting the melanocyte-derived peptides’ uptake, processing, and presentation to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [24,25]. Moreover, the lower expression of epithelial adhesion molecules, such as discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1) and E-cadherin, enhances melanocytes’ damage and antigen exposure resulting in the promotion of autoimmunity [26]. Stressed vitiligo melanocytes release exosomes and inflammatory cytokines that lead to innate immune response induction and, subsequently, to adaptive immune response through the activation of autoreactive cytotoxic CD8+ T cells [27]. The latter produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ) leading to disease progression through IFN-γ-induced chemokine secretion from surrounding keratinocytes, which results in the recruitment of more T cells to the skin through a positive feedback loop [27]. The described activation of the IFN pathway perpetuates the direct action of CD8+ cells against melanocytes, facilitated by regulatory T-cell dysfunction [27]. Recent scientific advances have also led to a deeper understanding of the complex role played by a specific subtype of T cells: T-resident memory cells [28]. Indeed, CD8 tissue-resident memory T cells are responsible for long-term maintenance and potential relapse of vitiligo in patients through cytokine-mediated T-cell recruitment from the bloodstream [27]. Hence, Koebner’s phenomenon may be explained by the higher frailty of altered melanocytes, which results in the release of inflammatory mediators, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and melanocyte death in response to any skin trauma [26].

On the other hand, with regard to immune response activation and SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis, a central role is played by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) 2, mainly expressed in bronchial transient secretory cells and in type 2 alveolar cells [29]. In fact, it has been identified as the receptor molecule for the cellular entry of the virus, so when SARS-CoV-2 enters the body, the spike protein binds to the host cell through ACE2 allowing the virus to fuse with the cell membrane and to release the viral RNA into the cytoplasm [29]. The viral invasion of host cells promotes type-I interferon (IFN- α/β) and proinflammatory cytokine synthesis and secretion [30]. Spreading of the virus inside the body is contained by the action of antigen-presenting macrophage and natural killer (NK) cells [30]. Interestingly, the inhibition of IFN production by the N protein of SARS-CoV-2 represents a crucial stage for viral survival, whereas Th1-type immune response has a key role in virus clearance promotion [29]. Indeed, helper T cells promote the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B-cell (NF-kB) signaling pathway activation that leads to proinflammatory cytokine production [29]. Helper T cells also promote viral-specific antibodies secretion through the activation of T-dependent B lymphocytes [31]. Cytotoxic T cells directly kill virus-infected cells [29]. After the invasion of the respiratory mucosa, the virus particles can infect other cells that possess the specific receptor, triggering a series of immune responses and producing a “cytokine storm” driven by IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, C-reactive protein (CRP), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (MCSF), interferon-gamma inducible protein (IP) 10, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP) 1, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) 1α, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α [30]. The “cytokine storm”, with the aim of reducing the viral spread, initiates inflammatory-induced lung injury with life-threatening complications such as multiorgan failure (MOF), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, hemorrhage and thrombosis, acute heart/liver/kidney injury, and secondary bacterial infections [29]. As of 7 September 2022, there have been 603,711,760 COVID-19 confirmed cases, including 6,484,136 deaths globally reported to the World Health Organization (WHO). As of 4 September 2022, a total of 12,540,061,501 vaccine doses have been administered [31].

Since the COVID-19 outbreak has changed our health programs in the last months, vaccination has become a daily practice. However, the temporal relationship between the vaccine and development of some skin conditions makes vitiligo development after prophylaxis more than just a coincidence [1,32]. Based on genetic susceptibility, some patients presented with different reactions linked with vaccine administration. Possible pathogenesis remains unclear, although the immune mechanisms underlying both the cutaneous conditions and action of the drug have been called into question, including antigen presentation, cytokine production, epitope spreading, and polyclonal activation of B cells involved in both the anti-infectious immune response as well as in autoreactivity [1,10,33]. In particular, with regard to vitiligo, melanocytes may have represented an unintentional target for antibodies and immune cell responses [10]. Given that the development of vitiligo involves the destruction of melanocytes by autoreactive CD8+ T cells, and successful vaccination also involves an extensive CD8+ T-cell response, this hypothesis may be plausible [10]. Another triggering mechanism may be the production of type I interferons (IFN-I) by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) caused by vaccination [34,35]. Indeed, IFN-I and pDCs play a crucial role both in the defense against SARS-CoV-2 and the activation of the immune response in vitiligo [34,35]. Finally, the IFN-I-mediated immune response induced by vaccination may be linked to the concurrent development of autoimmune disorders such as vitiligo.

Similarly, dealing with cutaneous autoimmune diseases, psoriasis flares, both de novo onset and recrudescence, has been described [36,37,38]. The possible role of viral proteins and vaccine adjuvants as triggers for immune dysregulation has been assumed, leading to the inflammatory cascade through IL-6 production and recruitment of Th17 cells [32,39]. No differences in the type of causing vaccine or correlations with the type of psoriasis were recorded, whereas variable response to treatment and clinical outcomes resulted [36,37,38].

In particular, a generalized pustular variant of psoriasis is driven by IFN-I itself, thus supporting the above-mentioned possible understanding of the association [38,40].

Anyway, with adverse cutaneous reactions, the collection of data from large case series is fundamental, allowing for further deep studies and more reasonable explanations.

Our contribution through reviewing the medical literature with regard to such uncommon events represents a useful guidance for clinicians to detect and correctly manage these conditions, especially in times of unpredictable medical enemies.

5. Conclusions

As the reporting of autoimmune reactions following COVID-19 vaccination continues to expand, it is reasonable to include it in the list of possible triggers of de novo vitiligo lesions. A link between inflammatory cells involved in both the pathogenesis of vitiligo and mechanism by which the COVID-19 vaccination stimulates the immune system may be assumed, and physicians should be aware of such skin reactions to vaccinations, especially when dealing with genetically susceptible patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and writing, L.M.; data collection, L.P. and M.C.; original draft preparation, Y.I. and G.N.; writing—review and editing and supervision, C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Claudio Guarneri, M.D. and Giuseppe Nunnari, M.D. have received consultation fees and/or grants for research projects, advisory panels, and giving educational lectures from Pfizer. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ciccarese G., Drago F., Boldrin S., Pattaro M., Parodi A. Sudden Onset of Vitiligo after COVID-19 Vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022;35:e15196. doi: 10.1111/dth.15196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon D.E., Amerson E., Rosenbach M., Lipoff J.B., Moustafa D., Tyagi A., Desai S.R., French L.E., Lim H.W., Thiers B.H., et al. Cutaneous Reactions Reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 Vaccination: A Registry-Based Study of 414 Cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021;85:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marzano A.V., Genovese G., Moltrasio C., Gaspari V., Vezzoli P., Maione V., Misciali C., Sena P., Patrizi A., Of-fidani A., et al. The Clinical Spectrum of COVID-19–Associated Cutaneous Manifestations: An Italian Multicenter Study of 200 Adult Patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021;84:1356–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guarneri C., Venanzi Rullo E., Gallizzi R., Ceccarelli M., Cannavò S.P., Nunnari G. Diversity of Clinical Ap-pearance of Cutaneous Manifestations in the Course of COVID-19. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020;34:e449–e450. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aktas H., Ertuğrul G. Vitiligo in a COVID-19-vaccinated Patient with Ulcerative Colitis: Coincidence? Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022;47:143–144. doi: 10.1111/ced.14842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaminetsky J., Rudikoff D. New-onset Vitiligo Following MRNA-1273 (Moderna) COVID-19 Vaccination. Clin. Case Rep. 2021;9:e04865. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzum A., Micalizzi C., Molle M.F., Parodi A. New-onset Vitiligo Following COVID-19 Disease. Ski. Health Dis. 2022;2:e86. doi: 10.1002/ski2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López Riquelme I., Fernández Ballesteros M.D., Serrano Ordoñez A., Godoy Díaz D.J. COVID-19 and Autoimmune Phenomena: Vitiligo after Astrazeneca Vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022;35:e15502. doi: 10.1111/dth.15502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores-Terry M.Á., García-Arpa M., Santiago-Sánchez Mateo J.L., Romero Aguilera G. Facial Vitiligo After SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T721. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2022.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Militello M., Ambur A.B., Steffes W. Vitiligo Possibly Triggered by COVID-19 Vaccination. Cureus. 2022;14:e20902. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolaidou E., Vavouli C.H., Koumprentziotis I.A., Gerochristou M., Stratigos A. New-onset Vitiligo after COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination: A Causal Association? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022. online ahead of print . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Singh R., Cohen J.L., Astudillo M., Harris J.E., Freeman E.E. Vitiligo of the Arm after COVID-19 Vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2022. online ahead of print . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Schmidt A.F., Rubin A., Milgraum D., Wassef C. Vitiligo Following COVID-19: A Case Report and Review of Pathophysiology. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:47–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bukhari A.E. New-Onset of Vitiligo in a Child Following COVID-19 Vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:68–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uğurer E., Sivaz O., Kıvanç Altunay İ. Newly-developed Vitiligo Following COVID-19 MRNA Vaccine. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022;21:1350–1351. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koç Yıldırım S. A New-onset Vitiligo Following the Inactivated COVID-19 Vaccine. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022;21:429–430. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gamonal S.B.L., Gamonal A.C.C., Marques N.C.V., Adário C.L. Lichen Planus and Vitiligo Occurring after ChAdOx1 NCoV-19 Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Dermatol. Ther. 2022;35:e15422. doi: 10.1111/dth.15422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caroppo F., Deotto M.L., Tartaglia J., Belloni Fortina A. Vitiligo Worsened Following the Second Dose of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022;35:e15434. doi: 10.1111/dth.15434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okan G., Vural P. Worsening of the Vitiligo Following the Second Dose of the BNT162B2 MRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. Dermatol. Ther. 2022;35:e15280. doi: 10.1111/dth.15280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertolani M., Rodighiero E., de Felici del Giudice M.B., Lotti T., Feliciani C., Satolli F. Vitiligo: What’s Old, What’s New. Dermatol. Rep. 2021;13:9142. doi: 10.4081/dr.2021.9142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krüger C., Schallreuter K.U. A Review of the Worldwide Prevalence of Vitiligo in Children/Adolescents and Adults. Int. J. Dermatol. 2012;51:1206–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung A.K.C., Lam J.M., Leong K.F., Hon K.L. Vitiligo: An Updated Narrative Review. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2021;17:76–91. doi: 10.2174/1573396316666201210125858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iannella G., Greco A., Didona D., Didona B., Granata G., Manno A., Pasquariello B., Magliulo G. Vitiligo: Pathogenesis, Clinical Variants and Treatment Approaches. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016;15:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosenson J.A., Flood K., Klarquist J., Eby J.M., Koshoffer A., Boissy R.E., Overbeck A., Tung R.C., le Poole I.C. Preferential Secretion of Inducible HSP70 by Vitiligo Melanocytes under Stress. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:209–220. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Li S., Li C. Perspectives of New Advances in the Pathogenesis of Vitiligo: From Oxidative Stress to Autoimmunity. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019;25:1017–1023. doi: 10.12659/MSM.914898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seneschal J., Boniface K., D’Arino A., Picardo M. An Update on Vitiligo Pathogenesis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021;34:236–243. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergqvist C., Ezzedine K. Vitiligo: A Focus on Pathogenesis and Its Therapeutic Implications. J. Dermatol. 2021;48:252–270. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boniface K., Jacquemin C., Darrigade A.-S., Dessarthe B., Martins C., Boukhedouni N., Vernisse C., Grasseau A., Thiolat D., Rambert J., et al. Vitiligo Skin Is Imprinted with Resident Memory CD8 T Cells Expressing CXCR3. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018;138:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsang H.F., Chan L.W.C., Cho W.C.S., Yu A.C.S., Yim A.K.Y., Chan A.K.C., Ng L.P.W., Wong Y.K.E., Pei X.M., Li M.J.W., et al. An Update on COVID-19 Pandemic: The Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Prevention and Treatment Strategies. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2021;19:877–888. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1863146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrahari R., Mohanty S., Vishwakarma K., Nayak S.K., Samantaray D., Mohapatra S. Update Vision on COVID-19: Structure, Immune Pathogenesis, Treatment and Safety Assessment. Sens. Int. 2021;2:100073. doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. [(accessed on 31 January 2022)]. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/

- 32.Talamonti M., Galluzzo M., Chiricozzi A., Quaglino P., Fabbrocini G., Gisondi P., Marzano A.V., Potenza C., Conti A., Parodi A., et al. Management of Biological Therapies for Chronic Plaque Psoriasis during COVID-19 Emergency in Italy. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020;34:e770–e772. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meduri A., Oliverio G.W., Mancuso G., Giuffrida A., Guarneri C., Venanzi Rullo E., Nunnari G., Aragona P. Ocular Surface Manifestation of COVID-19 and Tear Film Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:20178. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77194-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertolotti A., Boniface K., Vergier B., Mossalayi D., Taieb A., Ezzedine K., Seneschal J. Type I Interferon Signature in the Initiation of the Immune Response in Vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:398–407. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sa Ribero M., Jouvenet N., Dreux M., Nisole S. Interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and the Type I Interferon Response. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008737. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magro C., Crowson A.N., Franks L., Schaffer P.R., Whelan P., Nuovo G. The Histologic and Molecular Correlates of COVID-19 Vaccine-Induced Changes in the Skin. Clin. Dermatol. 2021;39:966–984. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elamin S., Hinds F., Tolland J. De Novo Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022;47:153–155. doi: 10.1111/ced.14895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Awada B., Abdullah L., Kurban M., Abbas O. Comment on ‘De Novo Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine’: Possible Role for Type I Interferons. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022;47:443. doi: 10.1111/ced.14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motolese A., Ceccarelli M., Macca L., Li Pomi F., Ingrasciotta Y., Nunnari G., Guarneri C. Novel Therapeutic Approaches to Psoriasis and Risk of Infectious Disease. Biomedicines. 2022;10:228. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gisondi P., Talamonti M., Chiricozzi A., Piaserico S., Amerio P., Balato A., Bardazzi F., Calzavara Pinton P., Campanati A., Cattaneo A., et al. Treat-to-Target Approach for the Management of Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Consensus Recommendations. Dermatol. Ther. 2021;11:235–252. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00475-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.