Abstract

Objective: Describes the activities of a clinical pharmacist in a gastroenterology (GI) clinic providing services to hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients, with a focus on practice management activities and tools. Practice Description: Located inside a GI specialty clinic in Fort Worth, Texas, the pharmacist provides comprehensive medication management under a collaborative practice agreement (CPA). Once referred by the GI physician, the pharmacist has face-to-face patient visits, develops the care plan, orders medications, and follows patients through sustained virologic response and the development of a hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance plan. Practice Innovation: The role of pharmacists in the management of HCV is important to understand. This article details a pharmacist-led clinic in an open GI medical practice. Evaluation: A retrospective chart review study was conducted to assess outcomes related to the integration of the clinical pharmacist. Methods: Completed by the study team, this study included manual chart reviews of patients with the ambulatory care pharmacist-driven HCV practice to pull data and information that were then tabulated using Qualtrics. Results: A total of 95 charts were surveyed, 78 records were created, and 49 patients were started on direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment by the pharmacist. Patients required multiple pharmacist communication actions. The minimum duration of the pharmacist service was 6 months and could extend more than 9 months depending on the time it took to get the patient started on medication. Pharmacist integration into the practice resulted in improved intake for the GI clinic, improved interprofessional interaction, and increased utilization of newer treatment modalities for HCV which feature cure rates up to 99% with limited side effects. Conclusion: Clinical pharmacists are well positioned to help navigate patients through the complexities of the medication use system, medication access, drug interactions and adverse effects, promote medication adherence, and allow patients to start and complete therapy.

Keywords: hepatitis C, antivirals, direct-acting antivirals, pharmacists, pharmacist-led service, clinical pharmacist practice site

Background

Coinciding with the nation’s opioid crisis, the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a blood-borne pathogen commonly transmitted through needle sticks during illicit drug use.1,2,3 Up to 85% of HCV infections are classified as chronic. 2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2 states that about 2.4 million patients are infected in the United States. Approximately 50% of those infected are asymptomatic and unaware they have been infected.2,4 Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are potential consequences, but not definitive in patients with untreated HCV. 3

The use of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) is the mainstay of therapy. A quantitative viral load of less than 15 IU/L determined by a rapid blood test indicates a virologic cure of HCV. A viral load is obtained 12 weeks after completing therapy, and if results indicate aviremia, it is considered a sustained virologic response (SVR12). 5

The first Global Health Sector Strategy on viral hepatitis was established by the World Health Assembly in 2016. The goal of this strategy is to eliminate viral hepatitis as a threat to the public by the year 2030 and aims for a 90% global reduction in new chronic HCV infections. 6 As of July 2022, there continues to be no vaccine for HCV. 2 However, efforts toward the elimination of HCV have improved through the use of DAAs and their dosing regimens.

Hepatitis C virus is a curable infection and continues to represent a financial burden to the health care system. The wholesale cost for DAAs used in the treatment of HCV ranges from $55 000 to $147 000 for a 12-week course of therapy. 5 Hepatitis C virus can also result in extrahepatic manifestations (EHMs) that contribute significantly to morbidity and cost of care. 7 These include but are not limited to type II diabetes mellitus, depression, cardiovascular disease, and chronic renal disease.8,9 According to Reau et al in her study published in 2017, the mean annual health care costs associated with EHMs in HCV was $17 416 per patient, that is, $10 866 more than a patient in a non-HCV cohort.8,9 Based on the study, annual health care costs associated with management of EHMs are estimated to exceed $10 billion.8,9 The use of pharmacists as HCV treatment providers using contemporary medication regimens was first described by Gauthier and colleagues in 2016. 10 Pharmacist-conducted HCV clinics have since been described in a variety of settings, including other federal systems, hospital-based clinics, and academic health systems.11 -13 The benefit of pharmacists in this field is clear, with reported SVRs ranging from 80% to 100%. One study comparing a pharmacist-managed clinic with a physician-run clinic in which the pharmacist provided a single consultative visit produced similar outcomes. 11 Although the pharmacist clinic was not found to be inferior to the physician-run clinic, it does not support a case for expansion of the pharmacist’s role in HCV treatment. Furthermore, few studies have described the pharmacist-led clinic model in an operationally detailed manner. Other outcomes that have not yet been assessed include the number of pharmacist interactions required in navigating patients to cure and the time to SVR12 that is achieved by a pharmacist-led HCV clinic.

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to describe the activities of a pharmacist embedded in gastroenterology (GI) specialty clinic providing services to patients diagnosed with HCV, including practice management details (ie, collaborative practice agreement [CPA] elements, number, and type of visits, visit components, and patient flow), number of pharmacist interactions, and time to SVR12. A secondary objective is to provide an account of how the practice was established and evolved so that other pharmacists can broaden their scope by adding evaluation and treatment of HCV. We will also describe the education, tools, and direction necessary to evaluate and treat patients with HCV and discuss specialty clinics as viable options for pharmacists to provide face-to-face patient care through expansion to this type of practice site.

Setting

Located at the Health Science Center in Fort Worth, Texas, HSC Health is an academic interprofessional clinical practice group that provides primary and specialty care for approximately 37 000 patients. About one-third of the patient population is Medicaid, low income, or under/uninsured, whereas the remainder consists of Medicare and commercial insurance beneficiaries. The interprofessional practice includes physicians, advanced practice providers, and pharmacists.

Practice Description

Prior to the integration of a pharmacist into the GI clinic, several pharmacists were already practicing in the family medicine and geriatrics clinics within the practice. Pharmacists in the HSC Health clinical practice group provide comprehensive medication management under a CPA with all physicians in the medical practice. Implemented in November 2017, the CPA included 47 disease states in which pharmacists were authorized to prescribe, modify, and discontinue medications; order laboratory tests and imaging; and conduct basic physical assessments.

Although the providers of the GI clinic had no previous experience working with a clinical pharmacist, they embraced a layered-learning approach and used attending providers, fellows, residents, and professional students to deliver interprofessional care. This approach facilitated the integration of the pharmacist and provided an opportunity for teaching and precepting a variety of learners.

Practice Innovation

A pharmacist was integrated into the GI clinic to help address the medication therapy needs of that population. The pharmacist was placed in an office within the GI specialty clinic and provided support by clinic personnel (ie, medical assistants, receptionist, nursing, and medical billing). As part of the initial implementation, practice leadership, physicians, and the clinical pharmacist collaborated to integrate the necessary medications, tests, and physical assessments into the working agreement to meet the needs of the HCV patient population (Table 1). The primary functions of the pharmacist were to prescribe medications related to HCV, leverage resources in securing these medications for patients, provide patient education, navigate insurance, encourage adherence, follow the patient from start to 12 weeks after treatment, and establish a HCC surveillance plan.

Table 1.

Excerpts From Drug Therapy Management (DTM) Protocol for Clinical Pharmacists Relevant to Gastroenterology Clinic.

| Diseases/ailments | Medication class | |

|---|---|---|

| Irritable bowel syndrome-C Irritable bowel syndrome-D Crohn’s disease Ulcerative colitis Cirrhosis Hepatitis C |

Pegylated interferons Direct-acting antivirals Ribavirin Adalimumab Ustekinumab Rifaximin Laxatives Neomycin |

|

| Laboratory tests | ||

| Basic/complete metabolic panel | Urine microalbumin/creatinine ratio | Complete blood cell count with differential |

| Lipid panel | Urine microalbumin | International normalized ratio (INR) |

| Hemoglobin A1c | Urinalysis | Prothrombin time (PT) |

| Free or total triiodothyronine (T3) | Fecal occult blood | C-peptide |

| Free or total thyroxine (T4) | Serum/urine calcium | Islet cell antibodies |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) | Serum phosphorus | Factor V Leiden |

| 1,25-hydroxy vitamin D | Gamma GT | Protein C |

| Liver function panel | Urine drug screen | Protein S |

| Liver enzymes | Creatinine phosphokinase | Antithrombin III |

| D-dimer | Uric acid | NS5A drug resistance |

| Vitamin B12 | Folate | Antiphospholipid antibody |

| Homocysteine | Factor Xa | Iron studies |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring | aPTT | Pregnancy test |

| HIV testing | Lupus anticoagulant | Hepatitis C virus genotype and subtype |

| Quantitative HCV RNA | HBsAg, anti-HBs, and anti-HBc | |

The pharmacist may provide the following drug therapy management activities in the supervising physician’s UNT Health practice site: (1) collect and review patient medication histories; (2) order or perform routine patient assessment procedures needed to optimize and monitor DTM, such as vital signs and diabetic foot examination; (3) order laboratory tests needed to optimize and monitor DTM; (4) order, modify, or discontinue drug therapy, including the authority to sign a prescription drug order for the dangerous drugs listed in this protocol following the diagnosis, initial patient assessment, and ordering of drug therapy by a physician; (5) select generically equivalent drugs if the physician’s signature does not clearly indicate that the prescription be dispensed as written; (6) order and administer the immunizations listed in this protocol; (7) order and administer epinephrine and/or diphenhydramine to treat reactions to immunizations administered by the pharmacist; and (8) any other DTM-related act delegated in this protocol.

The clinical pharmacists covered under this protocol may provide DTM for the following gastroenterology diseases and ailments and are authorized to prescribe, modify, or discontinue the medications and devices listed in the table. As pharmacists are unable to prescribe controlled substances, the following drug classes exclude controlled substances. The clinical pharmacists covered by this protocol are authorized to order the laboratory tests listed in the table for purposes of DTM.

Abbreviations: GT, glutamyl transferase; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; UNT, University of North Texas.

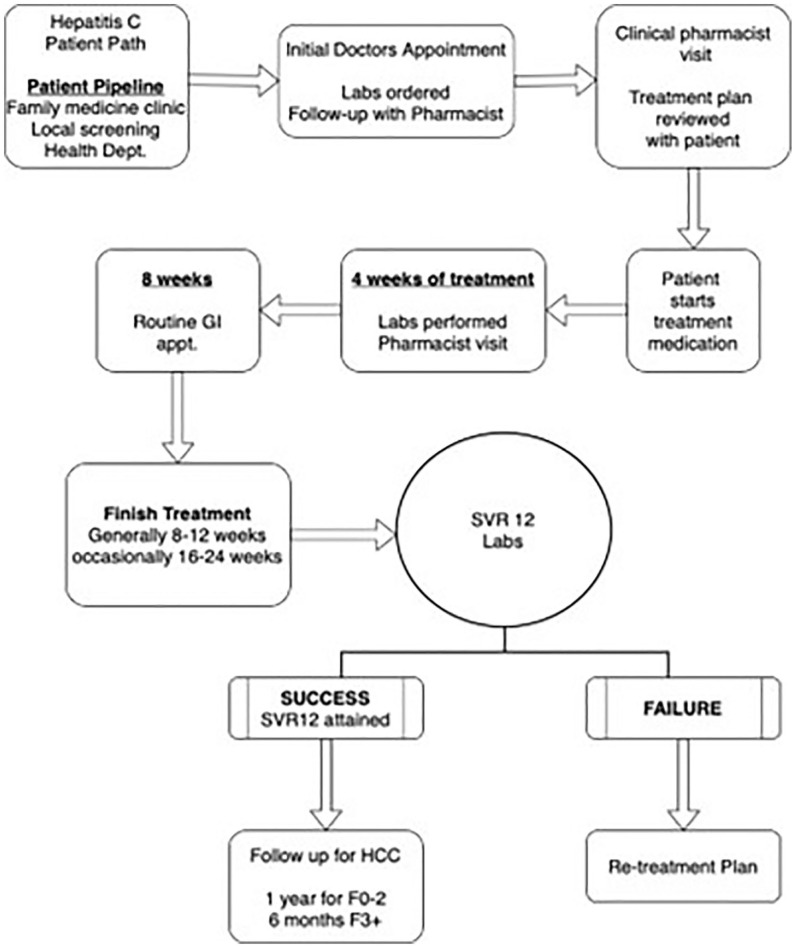

Patient intake and pharmacist visits are depicted in Figure 1. Referrals were promoted through a pop-up reminder in the electronic health record for patients who had not yet been screened for HCV. Diagnosed patients were seen by a GI physician and those eligible for treatment were referred to the pharmacist. Patients lost to follow-up from the prior HCV, service were identified, contacted, reevaluated, and treated.

Figure 1.

Patient intake, pharmacist visits, and follow-up service.

Abbreviations: GI, gastroenterology; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SVR, sustained virologic response.

Once referred, the initial pharmacist appointment was designed to determine whether the patient was agreeable to starting treatment. A summary of tasks completed at this initial visit is provided in Table 2. The fibrosis score, which indicates the severity of liver disease and cirrhosis, along with the genotype, is important in guiding therapy decisions. If the patient is willing to start treatment, the best possible medication history and reconciliation, which includes information from multiple sources, was performed. Next, the pharmacist would evaluate potential drug-drug interactions with DAA agents, most notably proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and amiodarone. In most cases, patients prescribed PPIs for recurrent heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease were switched to a histamine-2 receptor antagonist and advised to take it at an opposite time of day, apart from the DAA dose. Another medication class that should be discontinued is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Due to the increased risk for rapid progression of chronic kidney disease with NSAIDs, these medications were discontinued and switched to acetaminophen, with a reduced maximum daily dose of 2000 mg. 14 The hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors should be cautioned as patients are at increased risk of experiencing statin-associated myalgia symptoms while receiving a DAA. Pravastatin doses were reduced by 50% while on a DAA and then resumed at full dose upon conclusion of therapy. Rosuvastatin doses were limited to 10 mg, and atorvastatin, lovastatin, and simvastatin coadministration were avoided. Although no patient in the clinic was on amiodarone, QTc prolongation is a risk when combined with DAAs; patients already taking amiodarone would be cautioned regarding the symptoms of bradycardia and encouraged to monitor daily. Finally, the visit included a complete immunization history. Of note, DAA prescribing information warns about the potential reactivation of Hepatitis B. Therefore, the most recent American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) clinical guideline for the treatment of HCV recommends that patients be tested for active hepatitis B infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen and prior HBV infection. All susceptible patients should receive the hepatitis B vaccine prior to starting therapy. Once the first dose of the Hepatitis B vaccine has been administered, the DAA can be prescribed, and the patient can begin treatment upon receipt of the hepatitis treatment.

Table 2.

Summary of the Initial Clinical Visit.

| Initial clinic visit | |

|---|---|

| Past medical history | Medical conditions, surgeries, and imaging |

| Family history | Significant medical conditions, cancer, and/or reason for death |

| Social history | Use of alcohol, tobacco/nicotine, caffeine, cocaine, or other illicit drugs with appropriate probing questions |

| Vital signs | Blood pressure, heart rate, height, weight, and BMI |

| Vaccine history | Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, flu, pneumonia, shingles, and Tdap |

| Drug allergies | Medications, supplements, or food allergies |

| Medication reconciliation | Update and discuss medication list in health record, confirm diagnosis on record, and provide patient education as warranted |

| Review of systems | Related to GI and liver status via checklist in health record, that is, stools, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, reflux, heartburn, appetite, recent weight loss, blood in stool, or vomit |

| Coaching and education | Related to treatment of HCV and prevention of reinfection |

| Sign agreement | Document required by state Medicaid program indicating that the patient has been counseled regarding medication adherence and prevention measures to mitigate reinfection |

| Order labs and imaging | CBC, CMP, HCV Genotype, fibrosis scoring, hepatitis B assessment, HCG for women below the age of 50 years, PT/INR, urine drug screen, ultrasound of abdomen, which includes liver imaging, and refer to GI provider for colonoscopy if none found on record |

| Schedule the next appointment | Explain to the patient the expected number of pharmacist visits including 4 weeks after starting medication and 12 weeks after completing planned regimen. Phone communication, chart updates, and insurance navigation are ongoing between visits. |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CBC, complete blood cell count; CMP, comprehensive metabolic panel; GI, gastroenterology; HCG, human chorionic gondadotropin; HCV, hepatitis C virus; INR, international normalized ratio; PT, prothrombin time; Tdap, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis.

After this initial visit, patient agreement, review, and assessment of the patient, the clinical pharmacist made a treatment decision following the AASLD clinical guidelines and worked to secure patient access to medication. For patients with higher fibrosis scoring, F3 and F4, the prescription was expected to be covered by Medicaid and most insurance plans through the routine prior authorization process. If the pharmacy claim was denied for patients with low fibrosis scoring, namely, F0, F1, or F2, steps to obtain the medication through a patient assistance program (PAP) were initiated. Steps involved in approval by the PAP included an application form, a letter indicating a denied prior authorization, an appeal of the denial in which the appeal was upheld as denied, proof of income, the prescription, a clinical note from the electronic health record, and lab values within the past 90 days. Obtaining a PAP approval is time-consuming and can delay receipt of the medication.

Once the DAA was approved by the patient’s insurance, the pharmacist collaborated with various specialty pharmacies to assure initial and ongoing receipt of medication, document the date of the first dose, and reinforce critical patient counseling points to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse effects. Pertinent counseling points for DAAs included recommending that patients take the medication after the largest meal of the day and stay hydrated to reduce the onset of nausea or headaches. The second required face-to-face visit was scheduled 4 weeks after the first dose of the DAA. During this follow-up visit, 4-week labs were obtained, adherence to HCV treatment was discussed, and any adverse effects or other medical problems were addressed. Of note, a reduction in the HCV RNA quantitative viral load is expected and is often found to be undetected at 4 weeks from the start of therapy. This virologic response supports the notion of medication adherence. The patient is counseled regarding completion of the entire planned course of therapy and is scheduled for a final required appointment to occur 12 weeks after the end of the treatment regimen.

The third and final required face-to-face visit with the pharmacist was scheduled for 12 weeks after the final dose of DAA, at which point labs are ordered to validate SVR12. An HCV RNA quantitative result that shows “not detected,” a value of less than 15 IU/L, is deemed successful, with the patient being considered “cured” of HCV.5,15

For patients who completed the SVR12 lab draw, PCR results, maintenance planning, and healthy behaviors were discussed during a follow-up phone call or, in some cases, an in-person visit with the pharmacist. The potential for patients with a history of HCV to develop HCC was addressed by a monitoring and surveillance plan and a warm hand off back to the GI team. Future appointments were scheduled with a GI physician for HCC surveillance, that is, every 12 months for patients with fibrosis scores of F0, F1, or F2 and every 6 months for those with higher scores of F3 or F4. The HCC surveillance measures included a current ultrasound and Alpha-Fetoprotein laboratory test, which is a known tumor marker for HCC. 15

Evaluation

Outcomes of interest for the study included the number of patients treated, number of patients who completed the planned regimen, duration from the first appointment to receipt of medication, duration of time from the first appointment to SVR12, confirmed SVR12 of undetected, number of pharmacist clinical visits, time spent coordinating on behalf of the patient, and number of patients with an undetected viral load at 4 weeks after the start of a regimen that included a DAA. Qualtrics were used to gather information from patient charts. The time spent coordinating care on behalf of patients included clinical visits with the pharmacist, chart updates, and phone communications. The study was deemed exempt by the North Texas Regional Institutional Review Board.

Results

A snapshot of the study outcomes is provided in Table 3. Two years after the pharmacist service was implemented, a retrospective chart review was conducted: 95 charts were evaluated for inclusion and 17 charts were excluded due to being referred for reasons other than HCV or HCV treatment outside this pharmacist service. Only 78 data records were created; of those who started treatment, 87.76% (43/49) were presumed to have completed the regimen. Viral load testing at 4 weeks was completed for 77.5% (38/49), and the virus was undetected for these patients. The SVR12 testing was completed for 89.47% (34/38) of those who were also tested at 4 weeks. The time spent by the pharmacist on care coordination varied, with some patients receiving up to 5 interactions and some receiving up to 30. Interactions included navigating insurance, pharmacies, PAPs, direct patient education, and motivation to be successful through SVR12. The time from treatment plan to receipt of medication varied. The time to reach SVR12 varied from 6 to 18 months. Thirty-four patients confirmed SVR12 (34/49, 69.38%).

Table 3.

Results.

| 98 | Charts evaluated |

| 17 | Charts excluded |

| 78 | Data records created |

| 49 | Patients prescribed a DAA |

| 43 | Presumed to complete their regimen |

| 38 | Virus undetected at 4-week labs |

| 15 | Lost to follow up |

| 37 | Required up to 30 interactions |

| 21 | Required up to 20 interactions |

| 20 | Required up to 5 interactions |

| 27 | Were initiated on DAA within 4 weeks of first visit |

| 22 | Were initiated on DAA up to 12 months after first visit |

| 28 | Never started a DAA |

| 34 | Successfully confirmed SVR12, 34/49 = 69.38% |

Abbreviations: DAA, direct-acting antiviral; SVR = sustained virologic response.

Discussion

The integration of the pharmacist into practice resulted in improved intake for the GI clinic, improved interprofessional interaction, and increased utilization of newer treatment modalities for HCV, which featured a virological cure with a low incidence of adverse effects. Clinical success was dependent on referrals to the pharmacist service, and patient success was dependent on their level of engagement, interest, and effort to complete medication and laboratory work. It is important to note that the pharmacist’s weekly clinical service was limited to a total of 10 hours per week and this is when patients could be scheduled for face-to-face visits.

Koren et al, 16 whose study objective was to determine SVR rates for pharmacist-delivered HCV therapy in an open medical system, reported a 90% success rate for their patients with full adherence. Our HCV treatment success fell short of the 90% reported by Koren in that we were only able to confirm SVR12 in 69.4% of our patients. There are no comparable studies describing time on task by a clinical pharmacist in assisting the patient or the number of communication actions required in successful navigation for the patient.

Achieving the 2030 aim to eradicate HCV is bold and there are many barriers to effective treatment. The cost for DAAs used in the treatment of HCV is prohibitive to individual consumers, which amplifies the need for insurance coverage or the use of a foundation-sponsored PAP. In addition, lifetime costs associated with EHMs, cirrhosis, transplant, and HCC outpace treatment costs associated with HCV.6,7 Considering the financial and wellness burden to individuals and the health care system, interprofessional care that includes a pharmacist in advancing the treatment of HCV should be considered.

Clinical pharmacists can effectively contribute to meeting the 2030 aim in a variety of ways. Pharmacists are well positioned to mitigate drug-drug interactions, prevent adverse effects, promote adherence through comprehensive medication management, and assure medication access. Pharmacists have a unique understanding of prescription benefits and third-party insurer processes to assure that the appropriate medication is accessible to those patients.

Pharmacists with prescribing and ordering privileges in all practices should consider expanding their CPA to include ordering universal and risk-based HCV screening for all adults 18 years or older. Repeating HCV testing periodically for patients is encouraged for those with an increased likelihood of exposure to HCV, risky behaviors, injectable illicit drug use, or conditions and circumstances that put them at higher risk.15,17 The HCV antibody with Reflex to HCV RNA, Quantitative Real-Time PCR, is a guideline-based reflex blood test and is an efficient way to screen for HCV infection and establish a baseline viral load. 18

Community pharmacists can also play a vital role in achieving the 2030 aim. In a study published in 2019 examining pharmacist comfort and awareness of HIV and HCV point-of-care testing in community settings, only 1 in 5 pharmacists were aware that point-of-care testing for HCV was available. 19 To help meet the 2030 aim, community pharmacists can offer point-of-care clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA)-waived testing services. The OraQuick Rapid Antibody Test for HCV by OraSure is FDA-approved. 20 The blood sample is obtained through a finger stick, and results are available in 20 minutes. Most patients exposed to HCV will develop antibodies 6 months from the time of exposure. Upward of half of the individuals infected with HCV have not been diagnosed, and rates of screening remain low. 21 Patients with reactive results on rapid antibody test should be referred for additional testing. 22 In addition, the selection of patients to educate about HCV screening services within the community setting includes those who are on opioid substitution therapy as patients with a history of injection drug use are high risk and may be included in this cohort. 23

Conclusion

Although HCV is curable, barriers exist for patients to access the necessary pharmacotherapy to achieve a cure. Screening and detection are important to reaching patients with chronic HCV who may be unaware they are infected. As medication experts, clinical pharmacists are well positioned to help navigate patients through the complexities of the medication use system, monitor for drug interactions, prevent adverse effects, promote medication adherence, and encourage patients to start and complete therapy and required labs. Broadening pharmacist’s protocol to include evaluation and treatment of patients with HCV provides new practice opportunities for clinical pharmacists. Leveraging a pharmacist as the medication expert in a GI or HCV clinic can improve patient intake, medication access, and adherence to curative therapies.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official position of any affiliated institution.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jennifer T. Fix  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7958-1896

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7958-1896

Karl Meyer  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8134-2111

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8134-2111

References

- 1. Bailey JR, Barnes E, Cox AL. Approaches, progress, and challenges to hepatitis C vaccine development. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(2):418-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C fact sheet. Date unknown. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/index.htm.

- 3. Lingala S, Ghany MG. Natural history of hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2015;44(4):717-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C questions and answers for health professionals. Date unknown. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm.

- 5. Daniel KE, Saeian K, Rizvi S. Real-world experiences with direct-acting antiviral agents for chronic hepatitis C treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27(2):195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dhiman RK, Grover GS, Premkumar M. Hepatitis C elimination: a public health perspective. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17(3):367-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reau N, Vekeman F, Wu E, Bao Y, Gonzalez YS. Prevalence and economic burden of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus are underestimated but can be improved with therapy. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1(5):439-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carrozzo M, Scally K. Oral manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7534-7543. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reau N, Vekeman F, Wu E, Bao Y, Gonzalez YS. The prevalence and economic burden of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus are underestimated but can be improved with therapy. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1(5):439-452. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gauthier TP, Moreira E, Chan C, et al. Pharmacist engagement within a hepatitis C ambulatory care clinic in the era of a treatment revolution. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2016;56(6):670-676. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Naidjate SS, Zullo AR, Dapaah-Afriyie R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacist care delivery models for hepatitis C clinics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(10):646-653. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxz034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Geiger R, Steinert J, McElwee G, et al. A regional analysis of hepatitis C virus collaborative care with pharmacists in Indian health service facilities [published correction appears in J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:2150132718824513]. J Prim Care Community Health. 2018;9:2150132718807520. doi: 10.1177/2150132718807520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ourth HL, Groppi JA, Morreale AP, Jorgenson T, Himsel AS, Jacob DA. Increasing access for veterans with hepatitis C by enhancing the use of clinical pharmacy specialists. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(3):398-402. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2019.01.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gooch K, Culleton BF, Manns BJ, et al. NSAID use and progression of chronic kidney disease. Am J Med. 2007;120(3):280.e1-e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Association for the Study and Liver Diseases, Infectious Diseases Society of American. HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. Date unknown. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Koren DE, Zuckerman A, Teply R, Nabulsi NA, Lee TA, Martin MT. Expanding hepatitis C virus care and cure: national experience using a clinical pharmacist-driven model. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(7):ofz316. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghany MG, Morgan TR. Hepatitis C guidance 2019 update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases-Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2020;71:686-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Quest diagnostics test code 94345. Date unknown. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.questdiagnostics.com/healthcare-professionals/clinical-education-center/faq/faq194.

- 19. Min AC, Andres JL, Grover AB, Megherea O. Pharmacist comfort and awareness of HIV and HCV point-of-care testing in community settings. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21:831-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. OraQuick HCV rapid antibody test [package insert]. Bethlehem, PA: Orasure Technologies; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gardenier D, Olson MC. Hepatitis C in 2019: are we there yet? J Nurse Pract. 2019;15(6):415-419.e1. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended testing sequence for identifying current hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Published 2016. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/PDFs/hcv_flow.pdf.

- 23. Gunn J, Higgs P. Pharmacies dispensing opioid substitution therapy also play a role in hepatitis C virus elimination. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(3):245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]