Abstract

As one of the leading causes of death in women in Western developed countries, endometrial carcinoma (EC) is a common gynecological malignant tumor that seriously threatens women's health. In recent years, a trend has emerged of EC being manifested in younger women, and its overall incidence is gradually rising. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are novel endogenous transcripts that have limited ability to encode proteins due to their covalent closed-loop structure, which differs from that of other types of RNA. A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that circRNAs fulfill an important role in lung cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, EC and other malignant tumor types, and they can affect the occurrence and development of these malignancies through a variety of pathways, further demonstrating the potential of circRNAs as molecular biomarkers for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of malignant tumors. The purpose of the present review is to summarize the current understanding of the biogenesis and effects of circRNAs, and to discuss the expression, function and underlying mechanism of circRNAs in EC in order to identify potential novel biomarkers.

Keywords: circular RNAs, endometrial carcinoma, microRNAs, oncogenesis, epigenetic regulation

1. Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma (EC), also known as endometrial cancer, refers to a group of epithelial malignant tumors originating in the endometrium, and it is the most common gynecological malignant tumor in the United States in terms of incidence (1). EC ranks second among gynecological malignant tumors in China in terms of incidence, and its mortality rate is increasing year by year (2). EC accounts for ~85% of newly diagnosed cases, serous carcinoma accounts for 3–10%, clear cell carcinoma accounts for <5% and carcinosarcomas are relatively rare (3). The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system (4) is used for EC, which is divided into stages I–IV, and the survival rate decreases as the stage progresses (4). At present, the main screening methods for EC are hysteroscopy, segmented curettage and endometrial biopsy, and surgery combined with chemotherapy is the most common treatment for EC (5). The procedures involved include pelvic lymph node dissection, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and hysterectomy (6), and carboplatin combined with paclitaxel provides the means of first line chemotherapy (7). However, although therapies, including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, have provided good results (8), there is still an urgent need to identify novel molecular therapies to target the disease.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs/circs) are a class of endogenous non-coding RNA molecules that do not have 5′-end caps and 3′-end poly(A) tails (9), and form a circular structure with covalent bonds. They are abundant molecules that are less easily degraded by RNase R and are more stable than linear RNA (10). circRNAs are frequently ectopically expressed in a variety of malignancies, including bladder (11), colorectal (12), breast (13) and lung (14) cancer. circRNAs fulfill important phenotypic roles, including roles in proliferation, invasion, metastasis and drug resistance, in various types of malignancies, including bladder, colorectal, breast and lung cancer (11–14). circRNAs are also associated with tumor size, lymph node metastasis and cancer stage (15,16). Furthermore, certain circRNAs have been identified as molecular biomarkers for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of various types of human cancer (15).

In the present review, the biogenesis, classification and functions of circRNAs are summarized. Furthermore, the expression and biological functions of circRNAs that are involved in EC are reviewed.

2. Study design

In the present review, relevant literature was searched for using the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and Web of Science (http://wokinfo.com) databases, mainly focusing on the past 5 years (2017–2022), while a small number of studies identified were published >5 years ago. The search terms used were ‘endometrial carcinoma’ and ‘circRNAs’. The language limit was English. Two authors searched relevant literature according to the topic of this review. The inclusion criteria were: Inclusion of endometrial carcinoma and circRNAs or association with both. The exclusion criteria were: No association with endometrial carcinoma or circRNAs. Articles including the key words ‘endometrial carcinoma’ and ‘circRNAs’ were searched and cited. Two authors approved the final list of included studies.

3. Formation and classification of circRNAs

Numerous types of circRNA have been found to be expressed in a cell type-specific or tissue-specific manner (17,18), suggesting that they may fulfill biological functions. In the majority of eukaryotes, circRNAs, transcribed by RNA polymerase II and produced by spliceosomes, are covalently closed single-stranded RNA molecules that are formed through the reverse splicing of precursor mRNA (19,20). The precursor mRNA could be generated either through efficient canonical splicing to generate linear RNA, or by inefficient reverse splicing to generate circRNAs (9). circRNAs lack 5′-3′ ends and poly(A) tails, which render them less susceptible to RNase R degradation compared with linear RNAs, and thus, they are more stable than linear RNAs (10). There are three known mechanisms through which circRNAs may be formed, i.e., intron-pairing, lariat-driven circularization and RNA binding protein (RBP)-driven circularization (21). In the intron-pairing model, circularization via back-splicing is associated with base-pairing between different introns, particularly between repetitive sequences such as ALU repeats, whereas lariat-driven circularization occurs by adding splice sites of the exons that are skipped during linear RNA formation (22,23).

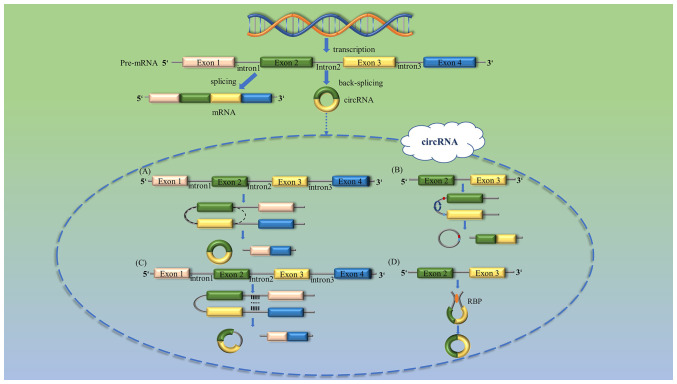

According to the method of splicing, circRNAs may be classified into four different types: Exonic circRNAs (Fig. 1A), intergenic circRNAs (Fig. 1B), intronic circRNAs (Fig. 1C) and exonic-intron circRNAs (Fig. 1D) (24,25). circRNA biogenesis is also regulated by trans-acting factors, such as RBPs (26). circRNAs are stable and specifically expressed both intracellularly and in extracellular fluid (27). Although circRNAs are generally expressed at low levels (27), increasing evidence has demonstrated that circRNAs are involved in EC (28–30). circRNAs carry multiple microRNA (miRNA/miR) binding sites, and regulate the activity of target miRNAs through their competitive binding, thereby inhibiting the transcription of downstream products (31). miRNAs are small non-coding single-stranded RNAs that bind to the 3′-untranslated region of mRNAs, thereby inducing mRNA degradation or inhibiting protein translation (32,33), and thus, the functions of miRNAs are closely associated with tumor cell development, proliferation, metastasis, invasion and amino acid transport (34,35). Targeted therapies that affect tumor cell proliferation, signal transduction, apoptosis, receptor activation and epigenetic modification offer major breakthroughs in terms of the treatment of human malignant tumors (36,37). For example, as a molecular target of neural tumors, the Bombesin-receptor family can achieve good therapeutic effect (38), and as a molecular target of ovarian cancer, AKT is essential for its treatment (37). circRNAs are becoming increasingly important in this field due to their relevance in the progression of malignant tumors (39).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the classification of circRNAs. According to the biogenesis characteristics from genomic regions, circRNAs are often divided into four types as follows: (A) ecircRNA (Lasso-driven cyclization); (B) IciRNAs (individual introns form rings directly); (C) ciRNA (introns are cyclized by base complementary pairing); and (D) EIcircRNAs (cyclization mediated by RBPs and trans-acting factors). circRNA, circular RNA; ciRNA, intronic circRNA; ecircRNA, exonic circRNA; EIcircRNAs, exonic-intron circRNAs; IciRNAs, intergenic circRNAs; RBP, RNA binding protein.

4. Biological functions of circRNAs

circRNAs act as sponges of miRNAs

miRNAs fulfill an important role in EC development. circRNAs act as natural ‘sponges’ for miRNA, thereby further affecting the functions of miRNAs (40). In 2013, Memczak et al (41) and Hansen et al (42) demonstrated that antisense circRNAs derived from cerebellum degeneration-related antigen 1 transcript (CDR1as) were able to act as miRNA sponges for mir-7 to regulate midbrain development in zebrafish. They also found that these circRNAs were located in the cytoplasm, and formed ribonucleoprotein complexes with miR-7 and argonaute proteins (41,42). These circRNAs contain >70 conserved binding sites for miR-7, enabling them to effectively inhibit its activity as a molecular sponge (41,42). Two circRNAs, CDR1as (ciRS-7) and circSry, were found to bind to, and possibly regulate, specific miRNAs (41,42). A growing body of evidence suggests that circRNAs may act as sponges of miRNAs by regulating transcription (43), translation or epigenetic changes of target genes by inhibiting miRNAs by enveloping the binding sites of RBPs (44). They have been demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of various biological processes and participate in the occurrence and development of different types of malignant tumor by enriching various forms of epigenetic modification (45–47). For example, circRNAs modulate biological processes such as invasion, proliferation and metastasis through methylation in bladder cancer (47) and gastric cancer (48). The potential use of circRNAs as therapeutic targets and biomarkers for human cancer types has been previously highlighted (14,30).

circRNAs and RBPs

RBPs are a class of proteins that are widely involved in gene transcription and translation (44). circRNAs partly exert their functions via interaction with RBPs in processes such as target gene genesis, translation, transcriptional regulation and extracellular transport (44). circRNAs are able to bind to different RBPs to form specific circRNPs (44), which are complexes formed by circRNAs and RBPs (44). The biological function of circRNAs can be regulated by RBPs through cycles driven by RBPs (21). Certain circRNAs may function as mRNAs, since they contain a large number of m6A modifications that are sufficient to drive protein translation in a catabolite activator protein-independent manner, as opposed to linear mRNAs, which initiate translation by ordinary ribosomal scanning (49). It has been demonstrated that RBPs are also involved in the translation of circRNAs (44). Exosomes can act as circRNA-loaded carriers to transfer genetic information between cells, and transport circRNAs into the extracellular environment (50). Various types of RBPs, including RNA binding motif protein 5, RNA binding motif protein 6 and putative RNA exonuclease NEF-sp, have been reported to act as intracellular inducers loaded with circRNAs in receptor exosomes to promote circRNA propagation in the mother cells (51). In order to explore the relationship between RBPs and circRNAs in more detail, it would be helpful to further explore the role of circRNAs in the pathophysiology of malignant tumors.

Translation of circRNAs

In 1995, researchers found that circRNAs, when translated, could yield repeated polypeptide chains based on the presence of a continuous open reading frame (ORF), but only when they contained internal ribosomal entry sites (IRESs) (52). Due to the lack of a 5′-cap in circRNAs, their translation needs to be initiated by a mechanism that does not rely on a cap structure (53,54). Recent studies have demonstrated that the translation of circRNAs can be initiated in two ways (53,54). The majority of circRNAs contain IRESs that are able to directly initiate translation (55). Downstream of the IRES is the ORF, and different circRNAs have their own unique ORFs, a feature that is also different from mRNA (55). At present, three different types of ORFs have been identified in circRNAs (55). The roles of circRNA-encoding peptides and proteins depend on the characteristics of overlapping amino acid sequences (56). The first ORF starts with the mRNA initiation codon ATG and ends with the termination codon TGA (57). A special sequence in this ORF is formed by a series of 5′-ends and 3′-ends in the reverse splicing that occurs after circRNA splicing (57). When ribosomes translate this sequence, a novel peptide is generated (57). The second ORF generates a new sequence, ‘UGAUGA’ or ‘UAAUGA’, from the 5′-ends and 3′-ends. This is called the overlapping start-stop codon, which encodes a new polypeptide when the ribosome reads the initiation codon AUG (56). The third ORF begins at the initiation codon (AUG) of the mRNA and is similar to the first ORF, with the exception that the final termination codon is formed by reverse splicing (58). Infinitely translatable circRNAs have also been created, with an infinite ORF, and no IRES, stop codon (59), 5′-cap or 3-poly(A) tail, but with the same ribosomal bound Shine-Dalgarno sequence and the AUG start codon (60).

circRNAs regulate parental gene transcription

Since circRNAs are regarded as splicing isomers, gene transcription may be regulated at various regulatory levels via translation into functional proteins, or by reducing the number of canonical splicing transcripts that can be translated into functional proteins (61). Muscleblind (MBL) is a post-splicing trans-splicing element, which is important in tissue-specific alternative splicing (61). The binding of splicing factor MBL protein to MBL motif located in the flanking intron may promote the formation of circRNAs via the MBL gene (61). A previous study revealed that certain exon loops that retain intron segments between exons were located mainly within the nucleus, and they regulated their parental genes through cis-modulation via specific RNA-RNA interactions (62). Several intron-retained circRNAs, such as circNCOR1, have been demonstrated to be associated with human RNA polymerase II and are localized within the nucleus, suggesting that they may regulate gene expression (62). Further research has indicated that these circRNAs may interact with U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein, thereby upregulating the expression of their parental genes (62). Although, during splicing, circRNAs and their corresponding colinear forms may compete with each other during biogenesis (19), the expression of circRNAs and mRNAs may be promoted simultaneously. circRNAs containing the initiation codon AUG may affect the expression of linear genes, whereas the linear transcripts used to splice circRNAs are forced to use another initiation codon for translation, resulting in a negative association between the transcription of certain circRNAs and their parent mRNAs (63), suggesting that circRNAs may inhibit the expression of their parent genes. This process also serves an important role in the occurrence and treatment of tumors. For example, circRNAs can regulate the transcription of parental genes through RNA-RNA interaction with U1 snRNA (62).

5. Differential expression of circRNAs in EC

With the progression of the second generation of high-throughput sequencing techniques, an ever-increasing number of circRNAs are being identified (52). Accumulating evidence has indicated the differential expression and diverse functions of circRNAs in EC (52,64,65). As shown in Table I, the upregulation and downregulation of circRNAs have been shown to participate in the pathological processes of EC, promoting or inhibiting EC.

Table I.

Dysregulated circRNAs in EC.

| First author, year | Gene symbol (circBase ID) | Function in EC | Expression | Downstream genes | PMID | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al, 2020 | circIFT80 (hsa_circ_0067835) | Promotes EC cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Upregulated | miR-324-5p/HMGA1 | 33169939 | (71) |

| Liu et al, 2020 | circWHSC1 | Promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of EC cells, and decreases apoptosis | Upregulated | miR-646/NPM1 | 32378344 | (28) |

| Hu et al, 2021 | circSLC6A6 | Promotes EC cell proliferation, migration and invasion | Upregulated | miR-497-5p | 34258297 | (29) |

| Liu et al, 2022 | circATP2C1 (hsa_circ_0005797) | Promotes EC cell proliferation and invasion | Upregulated | miR-298 | 34852711 | (30) |

| Fang et al, 2021 | circPOLA2 | Promotes cancer cell proliferation | Upregulated | miR-31 | 34539866 | (70) |

| Shu et al, 2021 | circZNF124 | Promotes cell proliferation, leucine uptake, migration and invasion in EC cells | Upregulated | miR-199b-5p/SLC7A5 | 34145797 | (67) |

| Yang et al, 2021 | circATAD1 | Suppresses EC cell invasion and migration | Downregulated | miR-10a | 34406448 | (74) |

| Wang et al, 2020 | circWDR26 (hsa_circ_0002577) | Promotes the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of EC cells | Upregulated | miR-625-5P | 32847606 | (76) |

| Li et al, 2021; | circCORO1C | Inhibits angiogenesis, proliferation, | Downregulated | / | 34534547 | (78) |

| Lee et al, 2016 | (hsa_circ_0000437) | migration and differentiation of EC cells | ||||

| Jia et al, 2020 | circESYT2 (hsa_circ_0001776) | Decreases cell proliferation and glycolysis, and enhances cell apoptosis | Downregulated | miR-182/LRIG2 | 32863771 | (69) |

| Yuan et al, 2021 | circZCCHC7 (hsa_circ_0001860) | Reduces EC resistance to MPA | Downregulated | miR-520h/Smad7 | 34912799 | (85) |

| Gu et al, 2021 | circTNFRSF21 (hsa_circ_0001610) | Promotes radiation resistance of EC cells | Upregulated | miR-139-5p | 34462422 | (89) |

| Shi et al, 2020 | circZNF700 (hsa_circ_0109046) | Promotes the proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of EC cells | Upregulated | miR-136/HMGA2 | 33173333 | (92) |

| Zong et al, 2020 | circPUM1 (hsa_circ_0000043) | Promotes EC cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and reduces apoptosis | Upregulated | miR-1271-5p/CTNND1 | 33128584 | (93) |

| Liu et al, 2020 | circTNFRSF21 (hsa_circ_0001610) | Promotes cell apoptosis and inhibits cell proliferation | Upregulated | miR-1227-MAPK13/ATF2 | 32299063 | (95) |

| Wu et al, 2021 | circFAT1 | Increases cell stemness | Upregulated | miR-21 | 34314629 | (96) |

| Shi et al, 2022 | circESRP1 | Promotes EC cell proliferation, migration, invasion and tumor growth | Upregulated | miR-874-3p | 35317822 | (97) |

The main functions and expression levels of circRNAs in EC are listed in the table. Additionally, downstream genes were identified and listed based on previous studies of the mechanisms, such as sponge adsorption. Some downstream genes are not explicitly shown in the cited literature, so ‘/’ is used instead. circRNA/circ, circular RNA; EC, endometrial carcinoma; miR, microRNA; PMID, PubMed reference number; /, not stated in reference.

Through high-throughput sequencing analysis, Ye et al (64) analyzed the differential expression of circRNAs in two grade (G)3 EC samples and adjacent non-cancerous endometrial tissues, and revealed that the levels of a total of 62,167 circRNAs were altered in G3 EC and para-carcinoma endometrial tissues. Among these, the levels of 25,735 circRNAs were elevated, whereas those of 36,432 were lowered (64).

Chen et al (65) found that, compared with in normal endometrial tissue, the total expression of circRNAs in EC tissues was lower, and mainly derived from exon transcription. By comparing six EC tissues and normal endometrial tissues, they found that 120 circRNAs were differentially expressed. Among the 120 differentially expressed circRNAs, a total of 22 circRNAs were upregulated in EC, whereas 98 were downregulated. Among the 120 differentially expressed circRNAs, 75 circRNAs were consistently expressed in EC and normal endometrial tissues, that is, they were either all upregulated or all downregulated in EC compared with normal endometrial tissues. The other 45 circRNAs were inconsistently expressed in all six EC samples.

In a clinical study, Xu et al (66) collected serum samples from 10 patients with EC and 10 matched (location-, age- and sex-matched) healthy patients. A total of 275 circRNAs were found to be differentially expressed in EC, including 209 circRNAs that were upregulated [the first two (hsa_circ_0002577 and hsa_circ_0109046) were screened from all the expression profiles]. Among the 66 circRNAs that were downregulated, the first two (hsa_circ_0109271 and hsa_circ_0098110) were screened from all expression profiles.

6. circRNAs in EC progression

The development of EC is a complex process, and cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis, resistance to treatment with drugs and radiation, glycolysis and angiogenesis are all involved in EC (67). Numerous tumor phenotypes, including cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis, resistance to treatment with drugs and radiation, glycolysis, and angiogenesis, are regulated by circRNAs (67–69).

circRNAs regulate cell proliferation and motility in EC

Proliferation, invasion and metastasis are the basic features of malignant tumors, involving a series of complex multi-step interactions among tumor cells and the host (70). For example, bladder cancer, gastric cancer (47,48) and EC all have the potential of proliferation, invasion and metastasis (70,71).

circRNAs are closely involved in the regulation of cell proliferation via multiple pathways. At present, several studies have demonstrated that circRNAs adsorb miRNAs through numerous pathways and fulfill a role in EC development (28,29,71). For example, circIFT80 [circBase ID (http://www.circbase.org/), hsa_circ_0067835], circWHSC1, circSLC6A6, circATP2C1 (circBase ID, hsa_circ_0005797) and circPOLA2 participate in the invasion, proliferation and metastasis of EC through the adsorption of miR-324-5p (71), miR-646 (28), miR-497-5p (29), miR-298 (30) and miR-31 (70), respectively. Notably, it has been reported that activation of these pathways depends on exogenous amino acids for energy (72).

Shu et al (67) reported that knockout of circZNF124 resulted in a marked reduction in the number of EC cells, decreased cell viability and colony formation, and decreased rates of invasion and leucine uptake. In EC, circZNF124 was demonstrated to be directly associated with miR-199b-5p, and miR-199b-5p was negatively regulated by circZNF124 (67). Solute carrier family 7 member 5 (SLC7A5), also known as L-type amino acid transporter 1, belongs to the family of L system transporters that transport amino acids, such as leucine and valine, into cells (73). SLC7A5 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and leucine uptake, and its overexpression can reverse circZNF124 silencing-mediated EC progression (67). These results indicate that circZNF124 may regulate the proliferation, migration and invasion of EC cells and their uptake of leucine via the miR-199b-5p/SLC7A5 signaling pathway, thereby promoting the development of EC (67).

Yang et al (74) analyzed the effects of circATAD1 overexpression on miR-10a expression and methylation through reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and methylation-specific PCR. Their study indicated that overexpression of circATAD1 led to a reduction in miR-10a expression and an increase in the methylation of the miR-10a gene, which indicated that circATAD1 may downregulate miR-10a through methylation to inhibit the invasion and migration of EC cells.

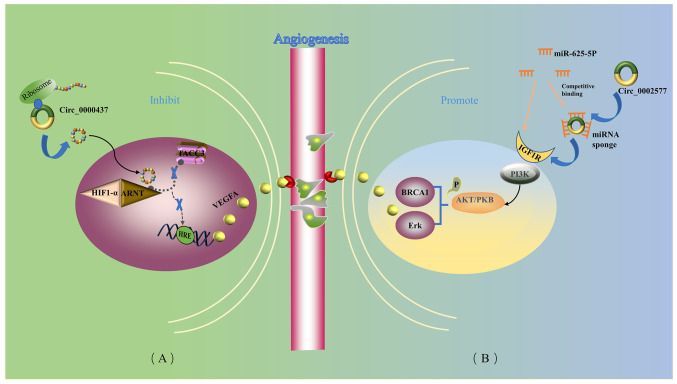

circRNAs are involved in the angiogenesis of EC

The formation of new capillaries in the existing vascular network, both into and inside the tumor, is essential for the growth and metastasis of EC (75). Therefore, inhibition of tumor angiogenesis is a strategy that may be employed to inhibit EC growth.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the proliferative ability of EC cells was enhanced following the upregulation of the expression of circWDR26 (circBase ID, hsa_circ_0002577), whereas knocking down its expression effectively inhibited the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of EC cells (76,77). Another key to tumor development is angiogenesis, the creation of a network of new capillaries that carry oxygen and nutrients needed for tumor tissue to grow (75). circWDR26 may act as a miRNA sponge to competitively bind with mir-625-5p and regulate its expression and function in cells (76). Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) has been identified as a downstream target of miR-625-5P in EC cells (77). IGF1R is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor involved in a variety of intracellular signaling pathways associated with tumors, including the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (77). Studies have demonstrated that circWDR26 is able to upregulate IGF1R, and activate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (77) by competitively binding miR-625-5p through sponging, thereby adversely affecting EC progression both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2) (76,77).

Figure 2.

Formation of new capillaries in the existing vascular network into and inside the tumor is essential for the growth and metastasis of EC. circRNAs are involved in angiogenesis in EC. (A) circ_0000437 reduces VEGFA expression by blocking the association between ARNT and TACC3, which negatively regulates tumor angiogenesis and leads to reduced angiogenesis. (B) circ_002577 competitively binds to miR-625-5p, resulting in the upregulation of IGF1R and subsequent activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which eventually leads to promotion of the formation of tumor blood vessels. Thick blue arrows indicate how circRNAs act. Blue lines indicate the product of the next step. Black arrows indicate causality. Dashed arrows indicate blocking. Yellow arrows indicate circRNAs acting as miRNA sponges. ARNT, aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator; circRNA/circ, circular RNA; EC, endometrial carcinoma; HIF1-α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α; HRE, hypoxia response element; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; miRNA/miR, microRNA; P, phosphate group; PKB, protein kinase B; TACC3, transforming acidic coiled-coil containing protein 3; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A.

Li et al (78) demonstrated that circCORO1C (circBase ID, hsa_circ_0000437) contains an ORF that encodes a functional peptide, which competitively binds to aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator and inhibits the coactivatory effect of transforming acidic coiled-coil containing protein 3 on the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) promoter, thereby suppressing the expression of VEGF (Fig. 2). CORO1C-47aa, which serves a role in the initiation of angiogenesis, not only inhibits angiogenesis, but also inhibits the proliferation, migration and differentiation of endothelial cells (78). circCORO1C expression was found to be downregulated in EC tissues compared with matched paracancerous non-cancer tissues (68). circCORO1C may serve an anti-angiogenesis role, and it is anticipated that it may have potential use in the treatment of EC (68).

circRNAs are involved in the glycolysis of EC

EC cells mainly obtain their energy through glycolysis to promote their proliferation (79). Therefore, inhibition of glycolysis is a further means through which EC may be treated by restraining the proliferation of EC cells, and effectively killing them.

Jia et al (69) reported that circESYT2 (circBase ID, hsa_circ_0001776) expression was downregulated in EC tissues compared with normal tissues, and in G3 EC tissues compared G1 + G2 EC tissues. Another study reported that the metabolic process of glycolysis fulfills a key role in the development of human malignant tumors (80), and the activation of glycolysis, with a consequent increase in lactic acid production, has been observed in a variety of different types of cancer cells, leading to changes in energy metabolism that are associated with the prognosis of patients with malignant tumors (81). By detecting the extracellular acidification rate and lactate 2 production, it is possible to confirm that circESYT2 can regulate glycolysis in EC cells (82). Leucine rich repeats and immunoglobulin like domains 2 (LRIG2) are mainly expressed in the ovary and uterus and serve an important role in the female reproductive system (82). circESYT2 acts as a sponge for miR-182 to regulate LRIG2 expression and inhibit tumor growth in vivo (69). circESYT2 is also able to promote cell apoptosis, inhibit cell proliferation and glycolysis, and inhibit the progression of EC via the miR-182/LRIG2 signaling axis (69).

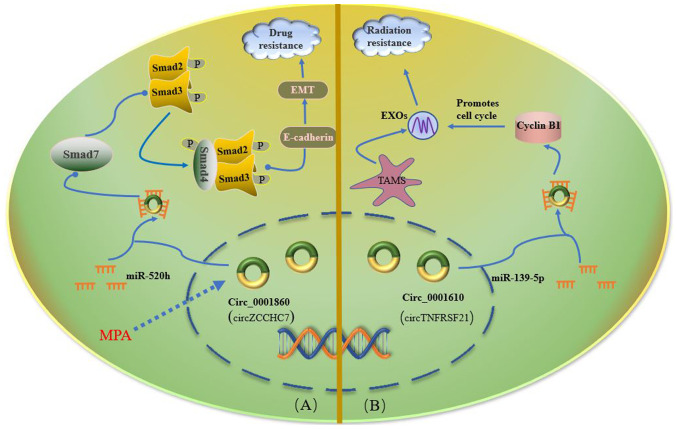

circRNAs are involved in drug and radiation resistance of EC

As aforementioned, surgery combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy is the most commonly used treatment for EC, whereas resistance to drugs and radiation poses a major difficulty in terms of the treatment of EC (5).

To protect the fertility of young patients with EC, the preferred drugs for maintenance therapy are medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and megestrol acetate (83). Although the therapy initially yields benefits, numerous patients with EC eventually develop resistance to progesterone; 63% of the patients do not respond when they receive MPA treatment again (84). In a study by Yuan et al (85), the differential expression of circZCCHC7 (circBase ID hsa_circ_0001860) in MPA-sensitive EC cells and MPA-resistant EC cells and tissues was first verified. circZCCHC7 was revealed to be downregulated in MPA-resistant EC cells and tissues. circZCCHC7 downregulation enhanced EC resistance to MPA via the miR-520h/Smad7 axis. It was subsequently demonstrated that circZCCHC7 acted as a sponge for miRNAs, acting as a tumor suppressor and fulfilling an important regulatory role in MPA-resistant and invasive EC (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Surgery combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy is the most commonly used treatment for EC, even though development of resistance to the drugs and radiation is an obstacle encountered in the treatment of EC. (A) circ_0001860 expression is upregulated in EC cells following MPA treatment, and circ_0001860 subsequently binds to miR-520h and regulates the expression and activity of Smad7, thereby inhibiting phosphorylation of Smad2/3, leading to the formation of the Smad2/3/4 complex, nuclear translocation of this complex and enhanced E-cadherin expression. Subsequently, increased E-cadherin expression can inhibit the progression of EC via EMT. (B) circ_0001610 can upregulate cyclin B1 expression by endogenously competing with miR-139-5p binding. Cyclin B1 is a vital promoter of radiation resistance in EC by regulating the cell cycle. Solid arrows indicate that the next step is the result of the previous step. The dashed arrow indicates external intervention. The solid round head indicates adjustment. Blue lines indicate circRNAs acting as miRNA sponges. circ, circular RNA; EC, endometrial carcinoma; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; EXOs, exosomes; miR, microRNA; MPA, medroxyprogesterone acetate; P, phosphate group; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage.

Radiotherapy is one of the adjuvant treatments for early-stage EC (86). This therapy induces apoptosis of the cancer cells by disrupting DNA double strands and inhibiting cell cycle checkpoint activation (86), thereby leading to improved survival rates of patients with early EC, and reductions in the local recurrence of cancer (87). However, radiation resistance affects the clinical progression of EC, and can lead to tumor recurrence (88). Compared with normal endometrial tissue, EC tissue has more evident infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) (89). There is evidence that TAMs are able to regulate cancer progression and are involved in the radiation resistance of EC cells (89). Gu et al (89) reported that circTNFRSF21 (circBase ID, hsa_circ_0001610) was abundant in M2-polarized macrophage-derived exosomes, which reduced the radiosensitivity of EC cells. circTNFRSF21 was also found to promote radiation resistance of EC cells (Fig. 3).

Other circRNAs in EC

Some researchers (90,91) have found that the circRNAs heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2 (HSPG2) and RP11255H23.4 are only expressed in normal endometrial tissues and are missing in EC tissues (90). They serve an important role in the pathogenesis of EC through competitive adsorption of corresponding miRNAs (90). Of the two circRNAs, HSPG2 is mainly involved in encoding the perlecan protein, a multidomain heparan sulfate proteoglycan (90), which affects endothelial growth or regeneration through binding with growth factors on the basement membrane, thereby inhibiting the progression of EC (91). circZNF700 (hsa_circ_0109046) promotes EC by acting as a competing endogenous RNA and indirectly upregulating high mobility group AT-hook 2 expression (92). In addition, downregulation of circZNF700 has been demonstrated to inhibit the proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of EC cells (92). Furthermore, circPUM1 serves the role of being a miRNA sponge, as it has been reported to bind to miR-136, promoting the proliferation, migration and invasion, and inhibiting the apoptosis, of EC cells (93). Destruction of the structure of circPUM1 led to a reduction in the tumorigenicity of EC cells in nude mice (93). A recent genome sequencing study has revealed that circTNFRSF21 (circBase ID, hsa_ circ_0001610) is upregulated in G3 EC compared with the adjacent non-cancerous tissues (64). A previous study on cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) has revealed that the tumorigenic ability of CSCs is greatly reduced following the knockdown of MAPK13, suggesting that MAPK13 may serve a role in tumor progression (94). MAPK13 is the target of miR-1227 in EC cells (95). Liu et al (95) revealed for the first time that the novel circRNA circTNFRSF21 could regulate MAPK13 expression via a competitive interaction with miR-1227, thereby activating the MAPK13/activating transcription factor 2 signaling pathway and promoting the formation of EC. circFAT1 has been revealed to be upregulated in EC, which leads to an increase in the cell stemness viability of cancer cells via upregulation of miR-21 (96). The cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein (CPEB) family is expressed differently in different types of tumors, thereby exerting an important role in the occurrence and development of tumors. circESRP1 has been demonstrated to act as a sponge for miR-874-3p to promote the EMT process through CPEB4, thereby promoting the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of EC cells both in vitro and in vivo, and promoting tumor growth in vivo (97).

Exosomal circRNAs in EC

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membranous vesicles secreted by a variety of cells, facilitating intercellular communication by transporting intracellular substances (91). Different RNAs can be transferred between cells through EVs (91,98). A previous study demonstrated that circRNAs are abundant and stable in exosomes (91). Secresome is a key factor in the formation of the tumor microenvironment (98). circRNAs are abundant and expressed stably in exosomes, and exosomes can be detected in body fluids (91). In the serum of patients with EC, the number of upregulated circRNAs has been reported to exceed the number of downregulated circRNAs (66). circRNAs regulate angiogenesis, drug resistance, immunity and metabolism via a range of different mechanisms (66). Tumor angiogenesis leads to a hypoxic microenvironment, which leads to acidification of the tumor microenvironment, affecting immune cell recognition and the response to tumor cells, subsequently leading to immunosuppression (99). In addition, tumor cells consume a large amount of glucose, limiting the use of glucose by T cells, an effect that both weakens the ability of T cells to kill cancer cells and maintains tumor growth and metastasis (99). Overall, circRNAs are stable, conserved and have specific expression patterns in cells and tissues, suggesting the possibility that circRNAs may function as molecular diagnostic and prognostic markers (100,101).

7. Conclusion and perspectives

It has been widely recognized that circRNAs fulfill important roles in the development and progression of EC (100,101). EC is a common malignant tumor of the female reproductive system (102). The incidence of EC has tended to increase in younger patients between 2006 and 2011 (102). Therefore, it is urgent to find regulatory factors of EC and to explore novel methods for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of EC. There is increasing evidence to suggest that circRNAs are closely associated with the regulation of the biological processes of human cancer, including EC (16,100,101). At present, circZNF124, circWDR26, circTNFRSF21, circESYT2 and circCORO1C have all been used as EC biomarkers (67,76). The present review discusses the roles of circRNAs in various phenotypes in EC, such as cell invasion and metastasis, drug and radiation resistance, glycolysis and angiogenesis, and elaborates the roles of circRNAs in EC in more detail. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first review that dealt with this subject. Compared with previous studies, such as the studies by Shi et al (101) and Takenaka et al (103), the innovation of this review lies in the first use of the phenotypic classification method to explain the topic. With the steady progress of RNA technology and its role in EC, it may be expected that research on the role of circRNAs in EC will have the potential to undergo great advances in the future. At present, circRNAs have been found to be abnormally expressed in numerous types of tumors; however, the abnormal expression of circRNAs has been reported to vary from disease to disease. Due to the complexity of tumor pathogenesis, the specific functions of circRNAs in EC are not yet fully clear, and circRNAs as biomarkers for EC disease diagnosis and prognosis require further study.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The present study was supported by a grant from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81972522) and Shenyang Medical College postgraduate Science and Technology Innovation Fund Project (grant no. Y20210520).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YLi and YW contributed to the conception and design of the paper. SG and TZ searched relevant literature according to the topic of this review. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SG. FM and YLu critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. YW and YLi approved the final list of included studies. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bell DW, Ellenson LH. Molecular genetics of endometrial carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang X, Tang H, Chen T. Epidemiology of gynecologic cancers in China. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29:e7. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks RA, Fleming GF, Lastra RR, Lee NK, Moroney JW, Son CH, Tatebe K, Veneris JL. Current recommendations and recent progress in endometrial cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:258–279. doi: 10.3322/caac.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YC, Lheureux S, Oza AM. Treatment strategies for endometrial cancer: Current practice and perspective. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29:47–58. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonoda Y. Surgical treatment for apparent early stage endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57:1–10. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2014.57.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombo N, Creutzberg C, Amant F, Bosse T, González-Martín A, Ledermann J, Marth C, Nout R, Querleu D, Mirza MR, et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO consensus conference on endometrial cancer: Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:16–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoki Y, Kanao H, Wang X, Yunokawa M, Omatsu K, Fusegi A, Takeshima N. Adjuvant treatment of endometrial cancer today. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50:753–765. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyaa071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LL, Yang L. Regulation of circRNA biogenesis. RNA Biol. 2015;12:381–388. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki H, Tsukahara T. A view of pre-mRNA splicing from RNase R resistant RNAs. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:9331–9342. doi: 10.3390/ijms15069331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Q, Liu T, Feng H, Yang R, Zhao X, Chen W, Jiang B, Qin H, Guo X, Liu M, et al. Circular RNA circSLC8A1 acts as a sponge of miR-130b/miR-494 in suppressing bladder cancer progression via regulating PTEN. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:111. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1040-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen RX, Chen X, Xia LP, Zhang JX, Pan ZZ, Ma XD, Han K, Chen JW, Judde JG, Deas O, et al. N6-methyladenosine modification of circNSUN2 facilitates cytoplasmic export and stabilizes HMGA2 to promote colorectal liver metastasis. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4695. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12651-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang G, Ling Y, Mehrpour M, Saw PE, Liu Z, Tan W, Tian Z, Zhong W, Lin W, Luo Q, et al. Autophagy-associated circRNA circCDYL augments autophagy and promotes breast cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:65. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li B, Zhu L, Lu C, Wang C, Wang H, Jin H, Ma X, Cheng Z, Yu C, Wang S, et al. circNDUFB2 inhibits non-small cell lung cancer progression via destabilizing IGF2BPs and activating anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun. 2021;12:295. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20527-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu J, Xu QG, Wang ZG, Yang Y, Zhang L, Ma JZ, Sun SH, Yang F, Zhou WP. Circular RNA cSMARCA5 inhibits growth and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1214–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rong Z, Xu J, Shi S, Tan Z, Meng Q, Hua J, Liu J, Zhang B, Wang W, Yu X, Liang C. Circular RNA in pancreatic cancer: A novel avenue for the roles of diagnosis and treatment. Theranostics. 2021;11:2755–2769. doi: 10.7150/thno.56174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng Q, Bao C, Guo W, Li S, Chen J, Chen B, Luo Y, Lyu D, Li Y, Shi G, et al. Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11215. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You X, Vlatkovic I, Babic A, Will T, Epstein I, Tushev G, Akbalik G, Wang M, Glock C, Quedenau C, et al. Neural circular RNAs are derived from synaptic genes and regulated by development and plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:603–610. doi: 10.1038/nn.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashwal-Fluss R, Meyer M, Pamudurti NR, Ivanov A, Bartok O, Hanan M, Evantal N, Memczak S, Rajewsky N, Kadener S. circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2014;56:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, Wang L, Ding J, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Che Y, Liu Z, Zhang X, Ye J, et al. Integrative analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana transcriptomics reveals intuitive splicing mechanism for circular RNA. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:3510–3516. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyu D, Huang S. The emerging role and clinical implication of human exonic circular RNA. RNA Biol. 2017;14:1000–1006. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1227904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang D, Wilusz JE. Short intronic repeat sequences facilitate circular RNA production. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2233–2247. doi: 10.1101/gad.251926.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang XO, Wang HB, Zhang Y, Lu X, Chen LL, Yang L. Complementary sequence-mediated exon circularization. Cell. 2014;159:134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang F, Nazarali AJ, Ji S. Circular RNAs as potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:1167–1176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen LL. The expanding regulatory mechanisms and cellular functions of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:475–490. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conn SJ, Pillman KA, Toubia J, Conn VM, Salmanidis M, Phillips CA, Roslan S, Schreiber AW, Gregory PA, Goodall GJ. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell. 2015;160:1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs co-precipitate with extracellular vesicles: A possible mechanism for circRNA clearance. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Chen S, Zong ZH, Guan X, Zhao Y. CircRNA WHSC1 targets the miR-646/NPM1 pathway to promote the development of endometrial cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:6898–6907. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu J, Peng X, Du W, Huang Y, Zhang C, Zhang X. circSLC6A6 sponges miR-497-5p to promote endometrial cancer progression via the PI4KB/hedgehog axis. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:5512391. doi: 10.1155/2021/5512391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Yuan H, He T. Downregulated circular RNA hsa_circ_0005797 inhibits endometrial cancer by modulating microRNA-298/catenin delta 1 signaling. Bioengineered. 2022;13:4634–4645. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.2013113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitra A, Pfeifer K, Park KS. Circular RNAs and competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks. Transl Cancer Res. 2018;7((Suppl 5)):S624–S628. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2018.05.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quévillon Huberdeau M, Simard MJ. A guide to microRNA-mediated gene silencing. FEBS J. 2019;286:642–652. doi: 10.1111/febs.14666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yates LA, Norbury CJ, Gilbert RJ. The long and short of microRNA. Cell. 2013;153:516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu L, Deng H, Hu J, Huang S, Xiong J, Deng J. The promising role of miR-296 in human cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:1915–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang X, Zhu X, Yu Y, Zhu W, Jin L, Zhang X, Li S, Zou P, Xie C, Cui R. Dissecting miRNA signature in colorectal cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2021;501:66–82. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padma VV. An overview of targeted cancer therapy. Biomedicine (Taipei) 2015;5:19. doi: 10.7603/s40681-015-0019-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shariati M, Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting AKT for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28:977–988. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1676726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moody TW, Lee L, Ramos-Alvarez I, Iordanskaia T, Mantey SA, Jensen RT. Bombesin receptor family activation and CNS/neural tumors: Review of evidence supporting possible role for novel targeted therapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:728088. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.728088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristensen LS, Jakobsen T, Hager H, Kjems J. The emerging roles of circRNAs in cancer and oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:188–206. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00585-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panda AC. Circular RNAs Act as miRNA sponges. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1087:67–79. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-1426-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, Kjems J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su M, Xiao Y, Ma J, Tang Y, Tian B, Zhang Y, Li X, Wu Z, Yang D, Zhou Y, et al. Circular RNAs in cancer: Emerging functions in hallmarks, stemness, resistance and roles as potential biomarkers. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:90. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zang J, Lu D, Xu A. The interaction of circRNAs and RNA binding proteins: An important part of circRNA maintenance and function. J Neurosci Res. 2020;98:87–97. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kristensen LS, Hansen TB, Venø MT, Kjems J. Circular RNAs in cancer: Opportunities and challenges in the field. Oncogene. 2018;37:555–565. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Mo Y, Gong Z, Yang X, Yang M, Zhang S, Xiong F, Xiang B, Zhou M, Liao Q, et al. Circular RNAs in human cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:25. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0598-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong W, Bi J, Liu H, Yan D, He Q, Zhou Q, Wang Q, Xie R, Su Y, Yang M, et al. Circular RNA ACVR2A suppresses bladder cancer cells proliferation and metastasis through miR-626/EYA4 axis. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:95. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1025-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Z, Rong Z, Luo Z, Yu Z, Zhang J, Qiu Z, Huang C. Circular RNA circNHSL1 promotes gastric cancer progression through the miR-1306-3p/SIX1/vimentin axis. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:126. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weingarten-Gabbay S, Elias-Kirma S, Nir R, Gritsenko AA, Stern-Ginossar N, Yakhini Z, Weinberger A, Segal E. Comparative genetics. Systematic discovery of cap-independent translation sequences in human and viral genomes. Science. 2016;351:aad4939. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janas T, Janas MM, Sapoń K, Janas T. Mechanisms of RNA loading into exosomes. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1391–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen CY, Sarnow P. Initiation of protein synthesis by the eukaryotic translational apparatus on circular RNAs. Science. 1995;268:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.7536344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xia X, Li X, Li F, Wu X, Zhang M, Zhou H, Huang N, Yang X, Xiao F, Liu D, et al. A novel tumor suppressor protein encoded by circular AKT3 RNA inhibits glioblastoma tumorigenicity by competing with active phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:131. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang WC, Wong CW, Liang PP, Shi M, Cao Y, Rao ST, Tsui SK, Waye MM, Zhang Q, Fu WM, Zhang JF. Translation of the circular RNA circβ-catenin promotes liver cancer cell growth through activation of the Wnt pathway. Genome Biol. 2019;20:84. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1685-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hellen CU, Sarnow P. Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1593–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.891101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng X, Chen L, Zhou Y, Wang Q, Zheng Z, Xu B, Wu C, Zhou Q, Hu W, Wu C, Jiang J. A novel protein encoded by a circular RNA circPPP1R12A promotes tumor pathogenesis and metastasis of colon cancer via Hippo-YAP signaling. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:47. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang Y, Gao X, Zhang M, Yan S, Sun C, Xiao F, Huang N, Yang X, Zhao K, Zhou H, et al. Novel role of FBXW7 circular RNA in repressing glioma tumorigenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:304–315. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Legnini I, Di Timoteo G, Rossi F, Morlando M, Briganti F, Sthandier O, Fatica A, Santini T, Andronache A, Wade M, et al. Circ-ZNF609 is a circular RNA that can be translated and functions in myogenesis. Mol Cell. 2017;66:22–37.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abe N, Hiroshima M, Maruyama H, Nakashima Y, Nakano Y, Matsuda A, Sako Y, Ito Y, Abe H. Rolling circle amplification in a prokaryotic translation system using small circular RNA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:7004–7008. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abe N, Matsumoto K, Nishihara M, Nakano Y, Shibata A, Maruyama H, Shuto S, Matsuda A, Yoshida M, Ito Y, Abe H. Rolling circle translation of circular RNA in living human cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16435. doi: 10.1038/srep16435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Konieczny P, Stepniak-Konieczna E, Sobczak K. MBNL proteins and their target RNAs, interaction and splicing regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:10873–10887. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Z, Huang C, Bao C, Chen L, Lin M, Wang X, Zhong G, Yu B, Hu W, Dai L, et al. Exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:256–264. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smid M, Wilting SM, Uhr K, Rodríguez-González FG, de Weerd V, Prager-Van der Smissen WJ, van der Vlugt-Daane M, van Galen A, Nik-Zainal S, Butler A, et al. The circular RNome of primary breast cancer. Genome Res. 2019;29:356–366. doi: 10.1101/gr.238121.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ye F, Tang QL, Ma F, Cai L, Chen M, Ran XX, Wang XY, Jiang XF. Analysis of the circular RNA transcriptome in the grade 3 endometrial cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:6215–6227. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S197343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen BJ, Byrne FL, Takenaka K, Modesitt SC, Olzomer EM, Mills JD, Farrell R, Hoehn KL, Janitz M. Analysis of the circular RNA transcriptome in endometrial cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;9:5786–5796. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu H, Gong Z, Shen Y, Fang Y, Zhong S. Circular RNA expression in extracellular vesicles isolated from serum of patients with endometrial cancer. Epigenomics. 2018;10:187–197. doi: 10.2217/epi-2017-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shu L, Peng Y, Zhong L, Feng X, Qiao L, Yi Y. CircZNF124 regulates cell proliferation, leucine uptake, migration and invasion by miR-199b-5p/SLC7A5 pathway in endometrial cancer. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2021;9:1291–1305. doi: 10.1002/iid3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee II, Maniar K, Lydon JP, Kim JJ. Akt regulates progesterone receptor B-dependent transcription and angiogenesis in endometrial cancer cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:5191–5201. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jia Y, Liu M, Wang S. CircRNA hsa_circRNA_0001776 inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in endometrial cancer via downregulating LRIG2 by sponging miR-182. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:412. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01437-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fang X, Wang J, Chen L, Zhang X. circRNA circ_POLA2 increases microRNA-31 methylation to promote endometrial cancer cell proliferation. Oncol Lett. 2021;22:762. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.13023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y, Chang Y, Cai Y. Circ_0067835 sponges miR-324-5p to induce HMGA1 expression in endometrial carcinoma cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:13927–13937. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hosios AM, Hecht VC, Danai LV, Johnson MO, Rathmell JC, Steinhauser ML, Manalis SR, Vander Heiden MG. Amino acids rather than glucose account for the majority of cell mass in proliferating mammalian cells. Dev Cell. 2016;36:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Q, Holst J. L-type amino acid transport and cancer: Targeting the mTORC1 pathway to inhibit neoplasia. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:1281–1294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang P, Yun K, Zhang R. CircRNA circ-ATAD1 is downregulated in endometrial cancer and suppresses cell invasion and migration by downregulating miR-10a through methylation. Mamm Genome. 2021;32:488–494. doi: 10.1007/s00335-021-09899-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ziyad S, Iruela-Arispe ML. Molecular mechanisms of tumor angiogenesis. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:1085–1096. doi: 10.1177/1947601911432334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Y, Yin L, Sun X. CircRNA hsa_circ_0002577 accelerates endometrial cancer progression through activating IGF1R/PI3K/Akt pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:169. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan J, Yin Z, Tao K, Wang G, Gao J. Function of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in cancer resistance to chemotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:41–47. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li F, Cai Y, Deng S, Yang L, Liu N, Chang X, Jing L, Zhou Y, Li H. A peptide CORO1C-47aa encoded by the circular noncoding RNA circ-0000437 functions as a negative regulator in endometrium tumor angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2021;297:101182. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu Q, Zhang W, Liu Y, Huang Y, Wu H, Ma C. Histone deacetylase 1 facilitates aerobic glycolysis and growth of endometrial cancer. Oncol Lett. 2021;22:721. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Helmlinger G, Sckell A, Dellian M, Forbes NS, Jain RK. Acid production in glycolysis-impaired tumors provides new insights into tumor metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1284–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Holmlund C, Nilsson J, Guo D, Starefeldt A, Golovleva I, Henriksson R, Hedman H. Characterization and tissue-specific expression of human LRIG2. Gene. 2004;332:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodolakis A, Biliatis I, Morice P, Reed N, Mangler M, Kesic V, Denschlag D. European society of gynecological oncology task force for fertility preservation: clinical recommendations for fertility-sparing management in young endometrial cancer patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1258–1265. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen M, Jin Y, Li Y, Bi Y, Shan Y, Pan L. Oncologic and reproductive outcomes after fertility-sparing management with oral progestin for women with complex endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yuan S, Zheng P, Sun X, Zeng J, Cao W, Gao W, Wang Y, Wang L. Hsa_Circ_0001860 promotes Smad7 to enhance MPA resistance in endometrial cancer via miR-520h. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:738189. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.738189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pawlik TM, Keyomarsi K. Role of cell cycle in mediating sensitivity to radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:928–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shinde A, Li R, Amini A, Chen YJ, Cristea M, Dellinger T, Wang W, Wakabayashi M, Beriwal S, Glaser S. Improved survival with adjuvant brachytherapy in stage IA endometrial cancer of unfavorable histology. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sorolla MA, Parisi E, Sorolla A. Determinants of sensitivity to radiotherapy in endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1906. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gu X, Shi Y, Dong M, Jiang L, Yang J, Liu Z. Exosomal transfer of tumor-associated macrophage-derived hsa_circ_0001610 reduces radiosensitivity in endometrial cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:818. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hasengaowa, Kodama J, Kusumoto T, Shinyo Y, Seki N, Nakamura K, Hongo A, Hiramatsu Y. Loss of basement membrane heparan sulfate expression is associated with tumor progression in endometrial cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Y, Zheng Q, Bao C, Li S, Guo W, Zhao J, Chen D, Gu J, He X, Huang S. Circular RNA is enriched and stable in exosomes: A promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res. 2015;25:981–984. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shi Y, Jia L, Wen H. Circ_0109046 promotes the progression of endometrial cancer via regulating miR-136/HMGA2 axis. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:10993–11003. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S274856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zong ZH, Liu Y, Chen S, Zhao Y. Circ_PUM1 promotes the development of endometrial cancer by targeting the miR-136/NOTCH3 pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:4127–4135. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yasuda K, Hirohashi Y, Kuroda T, Takaya A, Kubo T, Kanaseki T, Tsukahara T, Hasegawa T, Saito T, Sato N, Torigoe T. MAPK13 is preferentially expressed in gynecological cancer stem cells and has a role in the tumor-initiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;472:643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liu Y, Chang Y, Cai Y. circTNFRSF21, a newly identified circular RNA promotes endometrial carcinoma pathogenesis through regulating miR-1227-MAPK13/ATF2 axis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:6774–6792. doi: 10.18632/aging.103037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu W, Zhou J, Wu Y, Tang X, Zhu W. Overexpression of circRNA circFAT1 in endometrial cancer cells increases their stemness by upregulating miR-21 through methylation. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2021 Jul 27; doi: 10.1089/cbr.2020.4506. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi R, Zhang W, Zhang J, Yu Z, An L, Zhao R, Zhou X, Wang Z, Wei S, Wang H. CircESRP1 enhances metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in endometrial cancer via the miR-874-3p/CPEB4 axis. J Transl Med. 2022;20:139. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03334-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tan S, Xia L, Yi P, Han Y, Tang L, Pan Q, Tian Y, Rao S, Oyang L, Liang J, et al. Exosomal miRNAs in tumor microenvironment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:67. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01570-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lyssiotis CA, Kimmelman AC. Metabolic interactions in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:863–875. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guo J, Tong J, Zheng J. Circular RNAs: A promising biomarker for endometrial cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:1651–1665. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S290975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shi Y, He R, Yang Y, He Y, Shao K, Zhan, Wei B. Circular RNAs: Novel biomarkers for cervical, ovarian and endometrial cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2020;44:1787–1798. doi: 10.3892/or.2020.7780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, Chen T, Chen W. National estimates of cancer prevalence in China, 2011. Cancer Lett. 2016;370:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Takenaka K, Chen BJ, Modesitt SC, Byrne FL, Hoehn KL, Janitz M. The emerging role of long non-coding RNAs in endometrial cancer. Cancer Genet. 2016;209:445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.