Abstract

Background:

To determine if the “unaffected” hand in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy (CP) is truly unaffected.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective review of manual dexterity as measured by the Functional Dexterity Test (FDT) in 66 children (39 boys, 27 girls, mean age: 11 years 4 months) with hemiplegic CP. Data were stratified by Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) level, birth weight, and gestational age at birth, and compared with previously published normative values.

Results:

The FDT speed of the less affected hand is significantly lower than typically developing (TD) children (P < .001). The development of dexterity is significantly lower than TD children (0.009 vs. 0.036 pegs/s/year, P < .001), with a deficit that increases with age. MACS score, birth weight, and age at gestation are not predictors of dexterity. The dexterity of the less affected hand is poorly correlated with that of the more affected hand.

Conclusions:

Both dexterity and rate of fine motor skill acquisition in the less affected hand of children with hemiplegic CP is significantly less than that of TD children. The less affected hand should be evaluated and included in comprehensive treatment plans for these children.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, dexterity, Functional Dexterity Test, hemiplegia, less affected hand, contralateral hand

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) results from an irreversible, nonprogressive neurologic injury to the immature, perinatal brain.1-3 Although the cerebral injury is static in nature, it can result in progressive musculoskeletal pathology, including spasticity and/or contractures. 1 Hemiplegic, or unilateral, CP is the most common presentation with an incidence of 1 in 1300 live births.4,5 It is well known that children with hemiplegic CP have difficulty performing bimanual tasks. 6 However, there is mounting evidence that, despite having a unilateral cerebral lesion, the function in both hands is impaired to some degree. 5 ,7-9 Most studies focus on the more affected extremity and use the less affected extremity as a “normal” control for comparison. In these studies, the less affected hand is routinely referred to as “unimpaired” or “unaffected.”

An impairment of the less affected hand can be detrimental to the development of bimanual skills. It would be beneficial to identify and quantify the severity of any impairment of the less affected hand in children with hemiplegic CP. Further understanding of the functional deficits of the less affected hand would allow for a more comprehensive rehabilitative treatment plan. In our study, we chose to quantify the fine motor dexterity in the less affected hand using the Functional Dexterity Test (FDT), a timed peg-board test requiring use of tripod pinch and dexterous in-hand manipulation. This test was chosen for its sensitivity in detecting subtle fine motor deficits. These subtle differences may be missed by gross motor dexterity tests that focus on grasp and release, such as the 9-hole peg test and the Box and Blocks test (BBT). Published pediatric normative values for the FDT are available for comparison. 10

Our goals were to specifically assess the fine motor dexterity of the less affected hand in children with hemiplegic CP, to compare that dexterity with normative values from age-matched typically developing (TD) children, and to evaluate the rate of acquisition of dexterity with age. Subgroup analysis was performed to identify factors that could affect the dexterity level and development with age, including Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) level, gestational age, birth weight, and the dexterity of the more affected hand. Our hypotheses were that: (1) the dexterity of the less affected hand would be less than that of TD children; (2) the rate of dexterity acquisition with age would be slower than that of TD children; and (3) the dexterity of the more affected hand would correlate with the dexterity of the less affected hand.

Materials and Methods

Participants

With institutional review board (IRB) approval, we performed a retrospective review of prospectively collected data for all children seen in an upper limb CP specialty clinic from February 2012 to February 2013. Criteria for inclusion in this study were: age 3 to 18 years old; diagnosis of spastic hemiplegic CP; recorded dexterity evaluation, which is performed yearly as part of our routine clinical practice; and no history of surgery or Botox in the 6 months prior to the recorded dexterity evaluation. Participants were determined to have strictly hemiplegic (unilateral) CP based upon clinical examination, specifically a lack of spasticity in the less affected limb. Spasticity is defined as an increased to passive stretch. 11 A pediatric hand surgeon and a pediatric occupational therapist also routinely evaluated bilateral muscle tone, strength, sensibility, and posturing. Participants were excluded if they had any clinically evident findings consistent with bilateral involvement, did not have an FDT score recorded for their less affected hand, failed to meet the inclusion criteria, or had incomplete medical records. After cohort selection, we recorded each participant’s age, gender, gestational age, birth weight, MACS score, hand dominance, FDT scores, and BBT results. Data were collected from a single assessment point for each child during the study period.

Dexterity Tests

The FDT (North Coast Medical, Gilroy, California) is a timed pegboard test that provides objective assessment of in-hand manipulation and tripod pinch, a pattern of hand use that typically develops by 3 years of age. 12 Under the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), the FDT is a unilateral test of capacity. 13 The FDT consists of 16 cylindrical pegs arranged on a peg board in 4 rows of 4 pegs. Participants are instructed to pick up each peg, turn it over in their hand while refraining from supinating or touching the table with the peg, and re-insert it into the pegboard as quickly as possible, beginning with the top row and proceeding in a zigzag fashion through all 4 rows. For example, if the right hand is being tested, the child would begin at the left-most peg in the row farthest from him, complete that row from left to right, move to the peg directly below and complete the second row from right to left, continuing in this pattern until the end. For ease of use, we paint the pegs different colors on each end. One complete practice trial is performed to allow the child to learn the task, and the second trial is timed. The time taken to complete the test is measured with a stopwatch; results are recorded as number of pegs completed divided by time elapsed (seconds). This calculation (pegs per second) provides a measure of speed. When validated in adults, the FDT had excellent test-retest (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.95) and intra-rater (ICC = 0.91) reliability, and scores correlated well with the ability to perform activities of daily living. 14 Adult normative reference values have been recently updated. 15 In TD children, normative FDT speed (pegs/second) increase linearly with age for both dominant and nondominant hands at a constant rate of 0.037 pegs/s/year between the ages of 3 to 17 years. 10 Dominant hands are faster than nondominant hands at all ages and the differences remain constant. There is no gender difference through 17 years of age. These normative data were derived from a prospective study of 175 TD children aged 3 to 17 years (mean 9.4 years) There were 87 boys and 88 girls; 156 participants were right hand dominant. Ninety-three participants were white, 42 were African-American, 22 were Asian, 12 were Hispanic, and 6 were mixed-race, making it a diverse cohort. 10 All participants in the current study completed the FDT with their less affected hand. When able, they performed the test with their more affected hand as well. All FDTs were administered by a single trained clinician as described by Gogola et al. 10

The BBT is a timed dexterity test consisting of a wooden box divided into 2 equal compartments by a 15-cm high partition. 16 Children move as many of the 150-blocks as possible in 1 minute, one at a time, from one compartment over the partition and into the second compartment. The test is timed with a stopwatch and results reported as number of pegs moved in 1 minute. The BBT, a unilateral test of manual capacity, tests gross manual dexterity by requiring upper extremity movement (across the partition) and grasp and release. We routinely use the BBT to evaluate the more affected hand in children with hemiplegic CP.

Data Analysis

We compared this cohort’s FDT speed with age- and hand dominance-matched norms. 10 FDT speeds were stratified by MACS level, gestational age, and birth weight. For subgroup analysis, when comparing over a range of ages, it was necessary to account for speed differences based solely on age. Older children have better developed motor skills and faster dexterity speeds, so a normalized FDT speed deficit (age-matched normative speed minus subject’s speed) was used, instead of raw FDT speed. Gestational age was divided into preterm (before 37-weeks gestation) and term (equal or greater than 37 weeks gestation). Birth weight was divided into 1-kg segments for analysis to allow for a spectrum of comparisons. Although gestational age and birth weight are frequently correlated, these values are subject to recall bias as they are provided by the patient’s parent upon the initial history. Using both measures allows for better reliability of this analysis.

Statistical analysis was completed using data analysis tools available in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Seattle, Washington). Statistical significance was defined by an α-value < 0.05. For comparing FDT speeds in TD children to those with CP, a paired t-test was used. When comparing FDT deficits (ie, FDT speeds in TD children minus FDT speeds in CP) between subgroups, we used an independent t-test. An f-test for variance (ie, equal or unequal) was used to determine whether a parametric t-test could be used (shown in Table 1). For comparison of slopes, regression analysis was used to find significance of differences between slopes. Pearson correlation was used to analyze correlation, which was defined as “excellent” (>0.8), “good” (0.6-0.8), “fair” (0.4-0.6), or “poor” (<0.4). 17

Table 1.

Functional Dexterity Test Speed for Less Affected Upper Extremity in Children With Spastic Hemiplegic CP Versus TD Children. Data Shown Includes Overall Results and Subgroup Analysis.

| Subgroup | Number of children (%) | Mean ± SD in pegs/s | Range in pegs/sec | Mean ± SD in pegs/s | Range in pegs/s | P-value (variance) a CP vs. TD | FDT speed deficit ± SD (TD mean – CP mean) in pegs/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||||

| 66 (100%) | 0.491 ± 0.159 | 0.073-0.762 | 0.718 ± 0.144 | 0.423-0.989 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.227 ± 0.186 | |

| MACS b | |||||||

| MACS II | 23 (45%) | 0.559 ± 0.139 | 0.216-0.762 | 0.783 ± 0.098 | 0.593-0.948 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.224 ± 0.178 |

| MACS III | 21 (41%) | 0.450 ± 0.134 | 0.072-0.696 | 0.702 ± 0.137 | 0.508-0.971 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.252 ± 0.194 |

| Gestational age c | |||||||

| Preterm | 27 (41%) | 0.439 ± 0.154 | 0.119-0.762 | 0.705 ± 0.151 | 0.448-0.971 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.265 ± 0.172 |

| Term | 36 (55%) | 0.542 ± 0.142 | 0.073-0.762 | 0.728 ± 0.141 | 0.423-0.989 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.186 ± 0.183 |

| Birth weight | |||||||

| 0-1 kg | 7 (11%) | 0.445 ± 0.114 | 0.216-0.593 | 0.768 ± 0.144 | 0.567-0.971 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.323 ± 0.179 |

| 1-2 kg | 11 (17%) | 0.380 ± 0.166 | 0.119-0.640 | 0.632 ± 0.121 | 0.448-0.816 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.253 ± 0.160 |

| 2-3 kg | 10 (15%) | 0.516 ± 0.148 | 0.308-0.727 | 0.715 ± 0.138 | 0.546-0.948 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.200 ± 0.222 |

| 3-4 kg | 25 (38%) | 0.560 ± 0.145 | 0.073-0.762 | 0.743 ± 0.137 | 0.423-0.989 | <.001 (Eq) | 0.183 ± 0.176 |

| 4-5 kg | 2 (3%) | 0.582 ± 0.015 | 0.571-0.593 | 0.847 ± 0.142 | 0.746-0.948 | .228 (Not calc) | 0.265 ± 0.127 |

Note. MACS = Manual Ability Classification System; CP = cerebral palsy; TD = typically developing; FDT = Functional Dexterity Test.

Data variance was either equal (“Eq”), unequal (“Un”), or not calculated due to low numbers invalidating the equation (“Not calc”). The variance determined the t-test used (parametric vs. nonparametric).

MACS I, MACS IV, and MACS V were excluded due to low numbers.

“Preterm” was defined as less than 37-weeks gestation, while “Term” was defined as greater than or equal to 37-weeks gestation.

Results

Sixty-six children with hemiplegic CP had FDT results for their less affected hand available. There were 39 (59%) boys and 27 (41%) girls with a mean age at testing of 11-years 4-months (SD: 3 years 11 months, range: 3 years 11 months to 18 years 7 months). No child had undergone surgery on their less affected extremity. None of these children had participated in intensive, structured therapy programs, such as constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) or hand-arm bimanual intensive therapy (HABIT). Twenty-three (35%) were right-hand dominant and 43 (65%) were left-hand dominant. Sixty-three (96%) children considered their less affected hand to be their dominant hand.

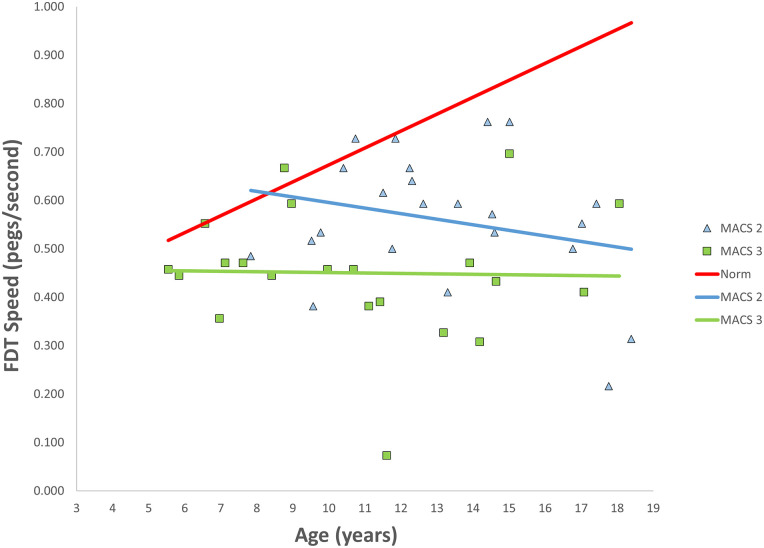

Overall, the dexterity of the less affected hand in children with CP was significantly slower than that of age-matched TD children (P < .001) as shown in Figure 1 (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.228) and Table 1. Dexterity in TD children, as measured by the FDT, increases linearly at a constant rate of 0.037 pegs/second/year. 10 Dexterity in the less affected hand of children with CP also showed a linear increase with age but at the significantly slower rate of 0.009 pegs/second/year (P < .001). Children with hemiplegic CP appear to start with the same dexterity potential as TD children. The 10 youngest children in the CP cohort (mean age = 5 year 7 months, SD = 11 months, range = 3 years 11 months to 7 years) showed no significant difference between their FDT speed compared to the TD children (P = .064). The 10 oldest children (mean age = 17 years 7 months, SD = 7 months, range = 16 years 9 months to 18 years 7 months) showed the greatest difference from TD children (P < .001).

Figure 1.

FDT speed of the less affected hand in children with hemiplegic CP plotted against age and hand-dominance matched norms. Both CP and norm FDT speeds increase with age, but at significantly different rates.

Note. FDT = Functional Dexterity Test; CP = cerebral palsy.

MACS level was documented for 51 (77%) children. There were 5 MACS I (10%), 23 MACS II (45%), 21 MACS III (41%), and 2 MACS IV (4%). MACS scores were unavailable for 15 (23%) children. Due to the low number of children in the MACS I and MACS IV groups, they were excluded from sub-group analysis. As with the whole cohort, both MACS II and MACS III FDT speeds were significantly slower than those of TD children (P < .001) (Table 1). There was no difference in speed deficits between MACS II and MACS III (P = .608). There was no significant difference (P = .416) between rate of dexterity development between MACS II (-0.012 pegs/s/year) and MACS III (-0.001 pegs/s/year) (Figure 2, Pearson correlation coefficient for MACS II = 0.245 and MACS III = 0.024).

Figure 2.

FDT speed of the less affected hands by MACS score compared with norms. There was no significant difference in the rate over time between MACS II or MACS III; they were both significantly slower than norms.

Note. MACS = Manual Ability Classification System; FDT = Functional Dexterity Test.

Gestational age at birth was documented for 63 (95%) children, with a mean of 35-weeks (SD = 5.8 weeks, range = 25-42 weeks). We compared the dexterity of the less affected hand between children born before 37 weeks gestation (preterm, n = 27, 41%) and those born at 37 weeks or beyond (term, n = 36, 55%). Neither the FDT speed deficit (P = .079) nor the rate of dexterity acquisition (P = .707) was significantly different between preterm (0.011 pegs/s/year) and term (0.007 pegs/s/year) children.

Birth weight was documented for 55 (83%) children with a mean of 2.6 kg (SD = 1.1 kg, range = 0.51-4.65 kg). We divided the cohort into 5 groups by 1-kg increments (Table 1). Within the first 4 weight groups, we found a significant difference (P < .001) between the FDT speeds and the normative values. In the fifth group, no significant difference was found (P = .228); however, given the small number of children in that group, no clinical conclusions can be drawn. There were no differences between the weight groups in FDT speed deficit or in rate of dexterity acquisition.

Twenty-three children (35%) were able to complete the FDT with their more affected hand. There was a significant difference (P < .001) in FDT speed when comparing the less affected extremity (mean = 0.449 pegs/s, SD = 0.171, range = 0.133-0.762) to the more affected extremity (mean = 0.266 pegs/s, SD = 0.149, range = 0.073-0.571) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference (P = .958) in the rate of dexterity acquisition between the 2 hands (0.002 pegs/s/year), with the less affected hand consistently 0.189 pegs/s faster. There was a poor correlation between the FDT speed in the more affected and less affected hands (r = 0.222).

Figure 3.

FDT speeds for both the less affected and more affected hands compared to dominant and nondominant hand normative values.

Note. The rate of dexterity development (slope) is conserved between the 2 hands in both cases; however, the constant difference between the 2 hands is more pronounced in children with CP. FDT = Functional Dexterity Test; CP = cerebral palsy.

The children who could not perform the FDT with their more affected hand (22 children; 33%) were evaluated with the BBT (mean = 16.3 blocks, SD = 7.5, range = 1-30). In order to compare these scores to each individual’s FDT speed of their less affected hand, the BBT scores were converted to speed, that is, the total number of blocks per second (mean = 0.272 blocks/s, SD = 0.126, range = 0.017-0.500). Again, there was a poor correlation between the 2 hands (r = 0.078).

Discussion

This study reports on the dexterity of the less affected hand in children with strictly hemiplegic CP. Dexterity is a central component of hand function, and is defined as “fine, voluntary movements used to manipulate small objects during a specific task.”14,18 It can be divided into gross motor dexterity, which is the ability to handle objects with the hand and arm (ie, grasp and release), and fine motor dexterity, the ability to manipulate objects within the hand. 18 To increase the sensitivity of our study, we chose a measurement outcome that involves fine motor dexterity. The less affected hand is widely regarded as “normal” or “unaffected,” and is consequently rarely evaluated. Our data show that the dexterity of the less affected extremity is much less than age-matched normative values, and that the rate of development of dexterity with age is slower than TD children. Although both hemiplegic and TD children start out with similar dexterity levels at younger ages, the gap in dexterity widens with age. The less affected hand may be more impaired, with less capacity for development, than previously believed. Alternatively, the slow rate of dexterity acquisition may be the result of compensatory adaptation over time due to lack of bimanual training.

Several authors have reported incidental findings of subtle deficits in the less affected extremity. Arnould et al 9 noted that hemiplegic children “also presented motor impairments in their nonparetic hand, especially in fine finger dexterity.” Sakzewski et al 8 noted that 66% to 71% of their children with hemiplegia scored greater than 2 standard deviations below the mean on the Jebsen-Taylor Test of Hand Function for their less affected hand compared to published norms. Steenbergen and van der Kamp 19 looked at grasp and release kinematics of the more affected extremity in adults with hemiplegic CP and commented that the “kinematics . . . were strikingly similar” between the “unimpaired” and “impaired” extremities. They hypothesized that the unilateral cortical injury responsible for CP might be the cause of deficits in both extremities. 19

The findings of this study agree with 2 prior studies demonstrating that the less affected hand is still affected to some degree regardless of the dexterity test utilized.20,21 Tomhave et al, 20 using the BBT, showed that the dexterity scores for both the affected and the contralateral hands were significantly lower than normative data for all groups studied. Rich et al, 21 using the Jebsen-Taylor Test of Hand Function, found that the less affected hand in children with hemiplegia underperformed the dominant hand of children with typical development. We used the FDT as it measures the more dexterous movement of in-hand manipulation, rather than simple grasp and release, allowing us to detect more subtle changes. Our study also differs from those previously published in that we reported on the rate of development of dexterity over time, and correlated it to the more affected hand. It is important to note that we are reporting cross sectional data of multiple children at a single time point rather than longitudinal data. Plotting FDT speeds versus age using a continuous age scale allows for visualization of not only the FDT speed at any fractional age, but also the rate of dexterity acquisition with age. This is not possible when dexterity results are grouped into arbitrary age categories.10,22 Prior work has shown that TD children acquire dexterity at a linear rate of 0.036 pegs/s for each year of age. 10 While this rate of increase is the same for dominant and nondominant hands, dominant hands are faster than nondominant hands by 0.088 pegs/s at all ages. Surprisingly, this linear relationship is maintained in children with hemiplegic CP, where both the less affected and more affected hands showed the same rate of dexterity development with age (0.002 pegs/s). However, the constant difference between the 2 hands was significantly larger at 0.189 pegs/s at all ages.

We stratified the cohort to investigate factors that could potentially affect fine motor dexterity and its’ development over time. Children were stratified by MACS level to see if the severity of global impairment correlated with the level of dexterity impairment. We did not find any significant differences in dexterity level or rate of dexterity development between MACS levels II and III. Similarly, there were no significant differences when dexterity was evaluated by gestational age at birth or birth weight. We hypothesized that a lower functional capacity in the more affected hand would result in better dexterity of the less affected hand, as it would be more likely to be used exclusively for activities and task completion. Instead, we found a poor correlation between the dexterity of the less affected and more affected hands, implying that the dexterity level in each hand is independent of the other. This finding held true whether the more affected hand showed higher (able to complete FDT) or lower (unable to complete FDT, but able to complete the BBT) level of function.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used cross-sectional data sampling, rather than longitudinally acquired data, to compare the development of dexterity with age. Second, the retrospective nature of the study means that the data were not collected specifically for this study and not all data were available for analysis. Third, the smaller numbers of children in the older age groups require caution when interpreting their results. Fourth, we used published normative FDT values, instead of a concurrently collected control group. However, the TD norms data were collected at the same institution as this study, using the same technique. Fifth, the identification of children with purely hemiplegic CP was based on strict clinical parameters only, without the use of advanced imaging or neurophysiology techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). This limits our ability to definitively exclude children with asymmetric bilateral hemiplegia.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that not only is the dexterity of the less affected hand in children with hemiplegic CP significantly impaired it develops at a slower rate than that seen in TD children. The level of dexterity in the less affected hand is not correlated to that of the more affected hand. We believe that the less affected extremity must be included in therapy programs in order to maximize its functional potential. Further research is needed to show whether early and intensive inclusion of the less affected extremity in treatment plans will impact that hand’s unimanual capacity, rate of dexterity development over time, or bimanual performance.

Footnotes

Author’s Note: This work has not been published previously, is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out, and that, if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright-holder.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animals Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Matthew B. Burn  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2689-2989

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2689-2989

References

- 1. Chin TYP, Duncan JA, Johnstone BR, et al. Management of the upper limb in cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop Part B. 2005;14(6):389-404. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200511000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shapiro BK. Cerebral palsy: a reconceptualization of the spectrum. J Pediatr. 2004;145(2 suppl):S3-S7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. 2007;109:8-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sköld A, Josephsson S, Fitinghoff H, et al. Experiences of use of the cerebral palsy hemiplegic hand in young persons treated with upper extremity surgery. J Hand Ther. 2007;20(3):262-272; quiz 273. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gilmore R, Sakzewski L, Boyd R. Upper limb activity measures for 5- to 16-year-old children with congenital hemiplegia: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(1):14-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sakzewski L, Ziviani J, Abbott DF, et al. Randomized trial of constraint-induced movement therapy and bimanual training on activity outcomes for children with congenital hemiplegia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(4):313-320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gordon AM, Bleyenheuft Y, Steenbergen B. Pathophysiology of impaired hand function in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(suppl 4):32-37. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sakzewski L, Ziviani J, Boyd R. The relationship between unimanual capacity and bimanual performance in children with congenital hemiplegia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(9):811-816. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arnould C, Penta M, Thonnard J-L. Hand impairments and their relationship with manual ability in children with cerebral palsy. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(9):708-714. doi: 10.2340/16151977-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gogola GR, Velleman PF, Xu S, et al. Hand dexterity in children: administration and normative values of the functional dexterity test. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(12):2426-2431. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.08.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bar-On L, Aertbeliën E, Molenaers G, et al. Manually controlled instrumented spasticity assessments: a systematic review of psychometric properties. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(10):932-950. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pehoski C. Objective manipulation in infants and children. In: Henderson A, Pehoski C, eds. Hand Function in the Child: Foundations for Remediation. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier; 2005:143-160. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stamm TA, Cieza A, Machold KP, et al. Content comparison of occupation-based instruments in adult rheumatology and musculoskeletal rehabilitation based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(6):917-924. doi: 10.1002/art.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aaron DH, Jansen CWS. Development of the Functional Dexterity Test (FDT): construction, validity, reliability, and normative data. J Hand Ther. 2003;16(1):12-21. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(03)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sartorio F, Bravini E, Vercelli S, et al. The Functional Dexterity Test: test–retest reliability analysis and up-to date reference norms. J Hand Ther. 2013;26(1):62-67; quiz 68. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathiowetz V, Federman S, Wiemer D. Box block test of manual dexterity: norms for 6–19 year olds. Can J Occup Ther. 1985;52:241-245. doi: 10.1177/000841748505200505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davids JR, Peace LC, Wagner LV, et al. Validation of the Shriners Hospital for Children upper extremity evaluation (SHUEE) for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(2):326-333. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yancosek KE, Howell D. A narrative review of dexterity assessments. J Hand Ther. 2009;22(3):258-269; quiz 270. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Steenbergen B, van der Kamp J. Control of prehension in hemiparetic cerebral palsy: similarities and differences between the ipsi- and contra-lesional sides of the body. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(5):325-332. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomhave WA, Van Heest AE, Bagley A, et al. Affected and contralateral hand strength and dexterity measures in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(5):900-907. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rich TL, Menk JS, Rudser KD, et al. Less-affected hand function in children with hemiparetic unilateral cerebral palsy: a comparison study to typically developing peers. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2017;31(10-11):965-976. doi: 10.1177/1545968317739997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holmefur M, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Bergström J, et al. Longitudinal development of hand function in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(4):352-357. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]