Abstract

Neurodegeneration is an increasing problem of aging. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) are the most frequent forms of age-related neurodegeneration. Infectious diseases, in general, confer a risk of AD. Influenza and pneumonia vaccinations reduce risk of AD. Being vaccinated against pneumonia between ages 65–75 is associated with a reduction in the risk of AD afterwards. Protection against bacterial and viral infection is beneficial to the brain since these infections may activate dormant herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) and herpes zoster virus (HZV). HSV-1 and HZV may interact to trigger AD. Shingles (HZV) vaccine Zostavax reduces risk of AD and PD. This finding is consistent with the link between viruses and neurodegeneration. Herpes virus-induced reactivation of embryologic pathways silenced at birth could be one of the pathologic processes in AD and PD. Once embryologic reactivation has occurred in the brain of an older person and AD or PD develops, this complex process relentlessly destroys the protective mechanism it created in utero. Unanswered question: Are the AD-risk-reducing effects of flu, pneumonia, and shingles vaccinations cumulative?

Neurodegeneration is an increasing problem of aging. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) are the most frequent forms of age-related neurodegeneration. Age-related neurodegenerative disorders tend to advance irreversibly and are associated with high socioeconomic and personal expenses, but few or no effective treatments are available (Hou et al., 2019).

Influenza, Pneumonia, and AD

Infectious diseases, in general, confer a risk of AD. But influenza and pneumonia vaccinations reduce risk of AD. 5.1% (n = 47,889) of flu-vaccinated patients and 8.5% (n = 79,630) of flu-unvaccinated patients developed AD during the 46-month follow-up (Bukhbinder et al., 2022).

Being vaccinated against pneumonia between ages 65–75 was associated with a reduction in the risk of AD afterwards (OR = 0.70; P < 0.04) in logistic model with all covariates. Largest reduction in the risk of AD (OR = 0.62; P < 0.04) was observed in the vaccinated against pneumonia non-carriers of rs2075650 G allele (risk factor for AD) (Ukraintseva et al., 2020).

Herpes and AD

Protection against bacterial and viral infection is beneficial to the brain since these infections may activate dormant HSV-1 and HZV. HSV-1 and HZV can interact to trigger AD (Cairns et al., 2022).

HSV-1 virus is implicated in the development of AD (Itzhaki, 2021). HSV-1 can produce neuroinflammation, which is associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Beta-amyloid in AD is antimicrobial and an inherited defense against HSV-1 (Lehrer and Rheinstein, 2020).

Shingles Vaccination, AD, and PD

Shingles (HZV) vaccine Zostavax reduces risk of AD. Lehrer and Rheinstein (2021b) found a 15% dementia risk reduction in vaccinated subjects. Lehrer and Rheinstein consulted The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the most comprehensive U.S. system of health-related telephone surveys, collecting data on U.S. citizens’ health-related risk behaviors, chronic health issues, and use of preventive services from across the country. Recognizing the importance of cognitive decline as a public health concern, the CDC Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Program created and deployed a BRFSS module to track subjective cognitive decline and its associated burden in the population in partnership with national experts. After thorough cognitive testing, the Cognitive Decline Module was originally introduced in 2011 as the Cognitive Impairment Module. Among the most predictive BRFSS module cognitive questions is one regarding interference with social activities. BRFSS participants are asked how often social activities are hampered by disorientation or memory loss. 61.6% of shingles-vaccinated subjects (n = 61) never had social activities hampered by disorientation or memory loss, whereas 46.6% of shingles-unvaccinated subjects (n = 82) never had social activities hampered by disorientation or memory loss. The result is significant (p = 0.025, two-sided Fisher exact test). Results of multivariate linear regression, social activities hampered by disorientation or memory loss dependent variable, shingles vaccination (yes or no), sex, and education level independent variables revealed that the effect of vaccination (reduced risk of social activities hampered by disorientation or memory loss) was significant (p = 0.03).

Lophatananon et al. (2021) found a 20% AD risk reduction in vaccinated subjects. Schnier et al. (2022) found reduced dementia incidence after varicella zoster vaccination in Wales 2013–2020. Vaccinated individuals were at reduced risk of dementia (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.72; 95% confidence interval: 0.69 to 0.75).

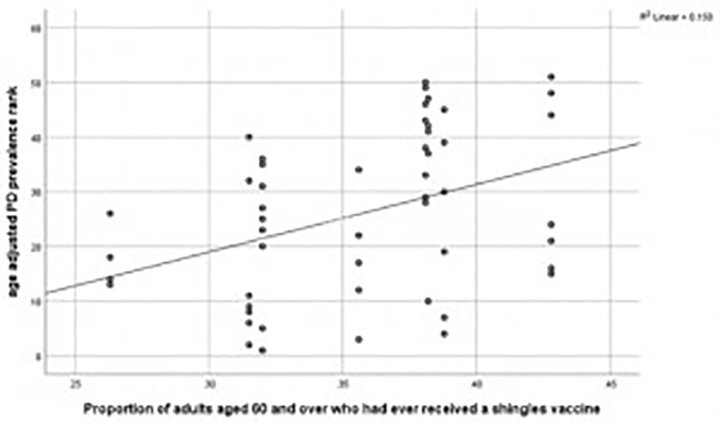

Shingles vaccination reduces risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Figure 1 shows that U.S. states with the most PD (lowest age adjusted prevalence ranks) had the lowest proportion of adults aged 60 and over who had ever received shingles vaccine (Lehrer and Rheinstein, 2022). States with the highest prevalence of PD are defined to be states with the lowest prevalence ranks of PD.

Figure 1.

. U.S. states with the most PD (lowest age adjusted prevalence ranks) had the lowest proportion of adults aged 60 and over who had ever received shingles vaccine (p = 0.005). States with the highest prevalence of PD are defined to be states with the lowest prevalence ranks of PD (Lehrer and Rheinstein, 2022).

The finding that shingles vaccination reduces the risk of AD and PD is consistent with the link between viruses and neurodegeneration. Herpes virus-induced reactivation of embryologic pathways silenced at birth could be one of the pathologic processes in AD and PD (Lehrer and Rheinstein, 2021a).

Unanswered question: Are the AD-risk-reducing effects of flu, pneumonia, and shingles vaccinations cumulative?

AD, PD, and Inflammation

About half of all dementia cases are caused by Alzheimer’s disease (Skoog et al., 1993), but the link between viruses, particularly herpes, and Alzheimer’s disease is controversial. There is some evidence that taking anti-herpes drugs for a short period of time reduces the risk of dementia. Infection without antiviral treatment increases the risk somewhat. However, the results do not appear to be consistent across European countries (Schnier et al., 2021). The finding that HZV vaccination reduces risk of dementia is consistent with the link between viruses and AD.

Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) are all part of a continuum that could explain a variety of age-related neurodegenerative symptoms. Inflammaging is an important part of this process since it is the long-term effect of persistent physiological stimulation of the innate immune system.

Inflammation is linked to aging and many age-related disorders. Chronic, sterile, low-grade inflammation, known as inflammaging, develops as people age and is linked to the etiology of age-related disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (Franceschi et al., 2018), cerebrovascular disease (Li et al., 2020), and diminishing adaptive immunity (Kasler and Verdin, 2021).

Because it may elaborate inflammatory chemicals and communicate with various organs and systems, the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in inflammaging. The gut microbiota has been linked to Parkinson’s disease. The protein alpha-synuclein misfolds in Parkinson’s disease. Misfolded proteins may transport a deranged signal to the brain via the vagus nerve, where misfolded alpha-synuclein has been related to PD symptoms (Fitzgerald et al., 2019; Willyard, 2021).

AD, PD, and Embryologic Reactivation of Processes Silenced at Birth

Neuroinflammation is associated with cytokines and growth factors in AD. Cytokines and neurotrophins have a significant impact on PD and Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) as well. Growth factors, neurotrophins, and cytokines are also involved in the development of the embryonic brain. In the preimplantation embryo, cytokines affect gene expression, metabolism, cell stress, and death. Around the time of birth, the genes that cause these changes are silenced. However, they could ruin the same neuronal structures they formed in utero if reactivated in the brain by inflammation (inflammaging) and viruses decades later.

GBA, BIN1, APOE, SNCA, and TMEM175 are five genes that have a role in contributing to whether a person will develop LBD, and some of these genes are also linked to AD and PD. AD, PD, and LBD lie on a continuum in vulnerable persons (Chia et al., 2021).

AD and PD embryologic reactivation is suggested by their progression. AD and PD do not spread willy-nilly within the brain. They progress in a predictable fashion, namely, the Braak stages (Braak et al., 2006; Burke et al., 2008). AD and PD represent a complex physiologic process gone awry. The advanced Braak stages V and VI are almost identical in AD and PD. In their end stages, AD and PD are difficult to distinguish clinically from one another.

Four characteristics of AD and embryologic reactivation

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) lessen the risk of Alzheimer’s disease but are ineffective as a therapy. NSAIDs lessen the risk of Alzheimer’s disease by suppressing inflammation. They are not, however, a cure because they are unable to silence the embryonic genes that have become active and are causing brain damage (Lehrer and Rheinstein, 2021a).

Children with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) have abnormal performance in learning and memory activities, which are assumed to be linked to the hippocampus, and some FAS children have abnormal hippocampal anatomy (Mattson et al., 2019). In an age-dependent manner, light to moderate wine drinking appears to lessen the risk of dementia and cognitive decline (Zhang et al., 2020). Alcohol disrupts the embryology of a fetus’s developing brain, lowering IQ. However, alcohol may interfere with embryologic reactivation in the elderly, lowering the chance of Alzheimer’s disease.

Within days of undergoing low-dose radiation treatment, patients with severe Alzheimer’s disease showed significant improvement in behavior and cognition (Cuttler et al., 2021). But ionizing radiation has a significant negative impact on the growing brain, IQ, and learning capacity (Hall et al., 2004).

The inconsistent association between herpes viruses and Alzheimer’s disease could be because herpes viruses are not a direct cause of the disease. The likelihood of embryologic reactivation and gene un-silencing is increased by herpes viruses.

Gene silencing and reactivation controlled by histones

The nucleus of every cell has two meters of DNA. To create chromatin, nucleosomes made up of eight histone proteins are first wrapped around the DNA. The tails of histones carry chemical modifications such as methylation, acetylation, and ubiquitylation, while nucleosomes also carry information about spacing. These alterations, or marks, tell the cells which genes to express and which to silence. Numerous proteins, along with remodelers and chaperones, have evolved to write, read, and remove the histone marks (Ash et al., 2022; Grau-Bove et al., 2022).

Advancing age is the greatest risk factor for AD. Chemical modifications carried by the tails of histones — methylation, acetylation, and ubiquitylation — silence genes. But the modifications are not bolted on with iron bands. Chemical forces hold them in place until the end of reproductive life. Thereafter evolution is indifferent as to what happens to them. With advancing age, the chemical modifications are dislodged by viruses, infections, and inflammaging. Embryologic pathways and processes silenced at birth are reactivated. AD, PD, and other forms of neurodegeneration are the result.

Cancer is an analogue. Cancer is a disease of aging. Many cancers develop after an accumulation of genetic mutations that occur with age (Campisi, 1997).

Conclusion

Embryologic reactivation is inexorable. Once embryologic reactivation has occurred in the brain of an older person and AD or PD develops, this complex process relentlessly destroys what the system created in utero.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this paper was supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure of the U.S. National Institutes of Health under award numbers S10OD018522 and S10OD026880. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

This work was presented at the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Meeting, Washington, D.C., 22 September 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/vaccines/nvac/meetings/2022/index.html

Contributor Information

Steven Lehrer, Specialty: Radiation Oncology, Institution: Department of Radiation Oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Address: 1 Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, New York, 10029, United States.

Peter H Rheinstein, Specialty: Legal Medicine, Drug Regulation, Institution: Severn Health Solutions, Address: 621 Holly Ridge Road, Severna Park, MD, 21146, USA.

References

- Ash C, Smith J, Hines PJ, Vinson V, Jiang D, Osborne IS, Wible B, Hurtley SM, Grocholski B. In Other Journals. Science 377(6602):167–168, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del TK. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 112(4):389–404, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhbinder AS, Ling Y, Hasan O, Jiang X, Kim Y, Phelps KN, Schmandt RE, Amran A, Coburn R, Ramesh S, Xiao Q, Schulz PE. Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease Following Influenza Vaccination: A Claims-Based Cohort Study Using Propensity Score Matching. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 88:1061–1074, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RE, Dauer WT, Vonsattel JPG. A critical evaluation of the Braak staging scheme for Parkinson’s disease. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 64(5):485–491, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns DM, Itzhaki RF, Kaplan DL. Potential Involvement of Varicella Zoster Virus in Alzheimer’s Disease via Reactivation of Quiescent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. J Alzheimers Dis, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aging Campisi J. and cancer: the double-edged sword of replicative senescence. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45(4):482–488, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia R, Sabir MS, Bandres-Ciga S, Saez-Atienzar S, Reynolds RH, Gustavsson E, Walton RL, Ahmed S, Viollet C, Ding J, Makarious MB, Diez-Fairen M, Portley MK, Shah Z, Abramzon Y, Hernandez DG, Blauwendraat C, Stone DJ, Eicher J, Parkkinen L, et al. Genome sequencing analysis identifies new loci associated with Lewy body dementia and provides insights into its genetic architecture. Nat Genet 2021. Feb 15. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00785-3. Online ahead of print., 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttler JM, Abdellah E, Goldberg Y, Al-Shamaa S, Symons SP, Black SE, Freedman M. Low Doses of Ionizing Radiation as a Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Pilot Study. J Alzheimers Dis 80(3):1119–1128, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald E, Murphy S, Martinson HA. Alpha-Synuclein Pathology and the Role of the Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurosci 13:369, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 14(10):576–590, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau-Bove X, Navarrete C, Chiva C, Pribasnig T, Anto M, Torruella G, Galindo LJ, Lang BF, Moreira D, Lopez-Garcia P, Ruiz-Trillo I, Schleper C, Sabido E, Sebe-Pedros A. A phylogenetic and proteomic reconstruction of eukaryotic chromatin evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 6(7):1007–1023, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P, Adami H-O, Trichopoulos D, Pedersen NL, Lagiou P, Ekbom A, Ingvar M, Lundell M, Granath F. Effect of low doses of ionising radiation in infancy on cognitive function in adulthood: Swedish population based cohort study. BMJ 328(7430):19, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch SG, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 15(10):565–581, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki RF. Overwhelming Evidence for a Major Role for Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV1) in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD); Underwhelming Evidence against. Vaccines (Basel) 9(6), 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasler H, Verdin E. How inflammaging diminishes adaptive immunity. Nature Aging 1(1):24–25, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein P. Shingles vaccination reduces risk of Parkinson’s disease. medRxiv, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH. Alignment of Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid-beta Peptide and Herpes Simplex Virus-1 pUL15 C-Terminal Nuclease Domain. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 4(1):373–377, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH. Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease May Result from Reactivation of Embryologic Pathways Silenced at Birth. Discov Med 31(163):89–94, 2021a. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH. Herpes Zoster Vaccination Reduces Risk of Dementia. In Vivo 35(6):3271–3275, 2021b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Huang Y, Cai W, Chen X, Men X, Lu T, Wu A, Lu Z. Age-related cerebral small vessel disease and inflammaging. Cell Death & Disease 11(10):1–12, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lophatananon A, Mekli K, Cant R, Burns A, Dobson C, Itzhaki R, Muir K. Shingles, Zostavax vaccination and risk of developing dementia: a nested case-control study-results from the UK Biobank cohort. BMJ Open 11(10):e045871, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Bernes GA, Doyle LR. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a review of the neurobehavioral deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 43(6):1046–1062, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnier C, Janbek J, Lathe R, Haas J. Reduced dementia incidence after varicella zoster vaccination in Wales 2013–2020. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 8(1):e12293, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnier C, Janbek J, Williams L, Wilkinson T, Laursen TM, Waldemar G, Richter H, Kostev K, Lathe R, G Haas J. Antiherpetic medication and incident dementia: observational cohort studies in four countries. European Journal of Neurology 28(6):1840–1848, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog I, Nilsson L, Palmertz B, Andreasson L-A, Svanborg A. A population-based study of dementia in 85-year-olds. New England Journal of Medicine 328(3):153–158, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukraintseva S, Yashkin A, Duan M, Akushevich I, Arbeev K, Wu D, Stallard E, Tropsha A, Yashin A. Repurposing of existing vaccines for personalized prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: Vaccination against pneumonia may reduce AD risk depending on genotype. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 16(S3):e046751, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Willyard C How gut microbes could drive brain disorders. Nature 590(7844):22–25, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Shen L, Miles T, Shen Y, Cordero J, Qi Y, Liang L, Li C. Association of Low to Moderate Alcohol Drinking With Cognitive Functions From Middle to Older Age Among US Adults. JAMA Network Open 3(6):e207922–e207922, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]