Abstract

Manganese has excellent performance in removing metal ions from aqueous solutions, but there are few studies on the adsorption and removal of heavy metal impurities in metal salt solutions. In this paper, the adsorption of cobalt and nickel ions in MnSO4 solution by δ-MnO2 prepared from two different manganese sources was studied. The optimum adsorption conditions were as follows: When the concentration of Mn2+ was 20 g/L, δ-MnO2 addition was 10 g/L, Co2+ concentration was 80 mg/L, Ni2+ concentration was 80 mg/L, reaction time was 60 min, reaction temperature was 80 °C, and pH value was 7, the adsorption rate of Co2+ and Ni2+ reached more than 80%. The manganese dioxide adsorbed by heavy metals was analyzed and detected. The results showed that MnOOH appeared in the phases of both kinds of δ-MnO2, and their morphologies were dense rod-like structures with different lengths and flake-like structures of fine particles. Co and Ni were distributed on the surface and gap of MnO2 particles, and the atomic percentage of Co was slightly higher than that of Ni. The new vibration peaks appeared near wave numbers of 2668.32, 1401.00, and 2052.19 cm–1, which were caused by the complexation of cations such as Co2 + and Ni2 + with hydroxyl groups. Some cobalt and nickel appeared on the surface of δ-MnO2, and the surface oxygen increased after adsorption. The above characterization revealed that the adsorption of cobalt and nickel in manganese sulfate by δ-MnO2 was realized by the reaction of its surface hydroxyl with metal ions (M) to form ≡SOMOH.

1. Introduction

Manganese sulfate is the most important and basic manganese source material for manganese-based lithium battery cathode materials.1−5 It is also the raw material for the preparation of manganese oxides, so it is of great significance to prepare high-purity manganese sulfate.6−9 In manganese ore, heavy metal cobalt and nickel often exist in the form of association. Therefore, when manganese ore is leached to obtain manganese sulfate, the impurity metals Co and Ni will also be leached one after another, resulting in the high content of heavy metal ions in the leached manganese sulfate solution, which seriously affects the quality of subsequent products. For example, the purity of manganese-based materials, especially the content of heavy metal impurities, is directly related to the specific capacity of the battery and the number of charge and discharge times.3 Battery-grade manganese sulfate has strict requirements on various metal impurity ions. The key to preparing high-purity manganese sulfate is to remove impurities. To obtain high-quality manganese-based battery materials, the purity of manganese-based raw materials must first be ensured. Whether it is manganese sulfate directly used to produce ternary materials or manganese oxide used to produce lithium manganate, it is necessary to first obtain manganese sulfate with high purity. Manganese sulfate is the most important and basic manganese source material for cathode materials of manganese-based power lithium batteries. So it is necessary to remove impurities in the manganese sulfate solution to obtain high-purity manganese sulfate products.10,11 The common impurity removal methods include the sulfide precipitation method,12−14 fluorination method,15−17 carbonation method,18,19 extraction method,20 and crystallization method.21,22 There are many shortcomings such as the long procedure, many control nodes, high requirements, high cost, large amount of slag, and low efficiency in the above processes. Therefore, developing an effective, short process with low environmental harm, low cost, and low slag removal has become a research hotspot in manganese sulfate production.

The adsorption method has been more and more widely used because of its simple process, good economic benefit, high treatment efficiency, and environmental friendliness,23−27 and the heavy metal ions in the adsorbent could be recycled by resolution so as to realize the regeneration and recycling of the adsorbent.28,29 Adsorption is the phenomenon of automatic diffusion and enrichment of molecules or ions between solid–liquid interfaces. According to this principle, the target molecules or ions are removed from the solution by using adsorbents with large specific surface area and high surface energy.30 MnO2 is an excellent adsorbent because of its rich surface hydroxyl, many defects, large specific surface area, and strong ion exchange capacity.

Manganese dioxide is mainly used in the field of adsorption to adsorb heavy metal ions in wastewater and alleviate the pressure of heavy metal pollution on the environment.31−37 Wang38 studied the adsorption properties of heavy metals antimony and thallium. δ-MnO2 had the best adsorption properties for Sb(III) and Tl(I), and its maximum adsorption capacities reached 120 and 498 mg·g–1, respectively. δ-MnO2 was prepared by Kong and Zhu39 in a laboratory method, and its adsorption properties for Zn2 +, Cd2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, and Co2+ in the mixed metal ion system was studied. The initial pH and adsorption time of the solution were investigated. Effect of coexisting ions and ionic strength on adsorption. The results showed that when the initial pH > 3.2, the adsorbent showed good removal effects on Zn2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Ni2+, and Co2+. The manganese oxide prepared by Kanungo et al.40 by the method of reducing potassium permanganate had a high adsorption capacity for heavy metal ions. Oscarson and Huang41 studied the removal of As(III) by δ, α, β state manganese dioxide. The results showed that the removal effect was related to the degree of crystallization and surface characteristics of manganese dioxide, indicating that δ, α state manganese dioxide with high activity can alleviate the toxicity of As(III) in the natural environment. Chen and Ye42 found that manganese dioxide had a strong adsorption effect on As(III) in the oxidation adsorption test of wastewater containing As(III) by pyrolusite, and the adsorption capacities of different forms of manganese oxides were also different. Two kinds of manganese dioxide, α-MnO2 and δ-MnO2, were prepared by Li.43 By controlling the single factor conditions, the main factors affecting the adsorption of nickel by manganese oxides were analyzed and studied. When the dosage was above 10 mmol, the adsorption rate of a 100 mL nickel solution with a 2 mmol/L concentration was close to 100%.

Although manganese dioxide has a good adsorption effect on heavy metal ions in water, the adsorption of heavy metal ions in high concentration metal salt solutions has been a difficult problem in the field of adsorption, and the related research is scarce. Some researchers investigated the effect of salt concentration (potassium salt, sodium salt, etc.) on the adsorption performance of manganese dioxide in the study of heavy metal ion adsorption. It was found that the adsorption amount of heavy metals was greatly weakened when there was a small amount of salt in the solution, and the adsorption amount was seriously slowed down with the increase of salt concentration. For the anion form of heavy metal impurity ions, the interference of salt solution was weak. In the mixed solution system of 80 g/L NaCl and 15 g/L Na2SO4, Yao44 studied the adsorption properties of flower-like manganese dioxide and sea-urchin-like manganese dioxide for trivalent arsenic. When the additive dosage was 30 g/L, the arsenic removal rates of the two adsorbents were 97.60 and 96.06%. The adsorption behavior of manganese dioxide on molybdenum ion in a manganese sulfate solution had been discussed by Xia et al.45,46 and Chen et al.47,48 Through in-depth analysis, it was found that the reason why arsenic ions and molybdenum ions can overcome the influence of high concentration salts mainly depends on the fact that both ions exist in the form of anionic groups such as H2AsO3–, HAsO32–, MoO4–, and HMoO4– in a certain pH range to be adsorbed by MnO2, while a large number of metal cations in high concentration salt solutions had limited obstacles to their anionic groups, so molybdenum ions in the manganese sulfate solution could be better adsorbed by manganese dioxide. However, there was no obvious effect on the metal ions in the cation form in the manganese sulfate solution.

To solve the problem of manganese dioxide adsorption of metal ions in the manganese sulfate solution, the adsorption mechanism of manganese dioxide was further studied. There are many studies on adsorption mechanism considering the influence of surface charge. The isoelectric point and zero charge of manganese dioxide are proposed,49 but the influence of surface defects and surface hydroxyl is less mentioned.50 Due to more or less defects, vacancies, and impurities in MnO2, oxygen coordination around manganese vacancies was unsaturated, resulting in the presence of a large number of hydroxyl groups. When MnO2 adsorbed heavy metal ions by surface hydroxyl complexation, the first effect was on pH.51 Therefore, Li Mingdong, of our research group, did the determination of different crystal MnO2 acid point pH,52 and he compared different crystal manganese dioxide adsorption of cobalt and nickel in manganese sulfate solution. He did the analysis of its influencing factors and explored the interaction between manganese dioxide and manganese sulfate solution.53 On this basis, this paper explored the process conditions of manganese dioxide adsorption of metal ions in heavy metal salt solutions, analyzed the surface hydroxyl complexation mechanism, and further studied the adsorption characteristics of MnO2 surface hydroxylation on heavy metal ions. The adsorption mechanism of impurity ions in high-salt solutions was theoretically clarified to solve the difficult removal of heavy metal ions in the manganese sulfate solution, the raw material of manganese battery. Using manganese dioxide to adsorb cobalt and nickel impurities in manganese sulfate, on the one hand, can provide a reference method for manganese sulfate impurity removal to achieve battery-level requirements; on the other hand, it can recycle the adsorbed nickel and cobalt metal impurities, which has important economic significance. In this paper, the mechanism of manganese dioxide adsorbing cobalt and nickel in the manganese sulfate solution had been studied. Adsorption conditions were explored only in a simpler manganese sulfate solution system. It is hoped that, in the future, this study can be used to adsorb cobalt and nickel in a more complex manganese sulfate solution system and provide reference for adsorbing other impurity ions in heavy metal salt solutions.

2. Result and Discussion

2.1. Study on the Adsorption Process

Researchers in our group had done a lot of preliminary work,53 and through the comparison of different crystal forms of manganese dioxide, the best adsorption performance was by δ-MnO2. δ-MnO2 prepared with different manganese sources was further studied, and the equi-acidity point pH,53 specific surface area, pore size, and pore volume of the isoacid point were detected. Studies had shown that when the pH of the electrolyte solution is higher than the equi-acidity point pH of MnO2, the surface hydroxyl groups undergo deprotonation reaction and complex with metal ions to release H+, reducing the pH value of the solution. When the pH of the solution was lower than the equi-acidity point pH, the protonation reaction of the surface hydroxyl mainly consumed H+, which increased the pH value. When the pH of the solution was the same as the equi-acidity point pH, the H+ was released by the surface hydroxyl complexation reaction and the protonation reaction consumed H+ in a dynamic equilibrium, and the pH value did not change. The pH value of the equi-acidity point of MnO2 is essentially the equilibrium pH value of the adsorption and desorption of the surface hydroxyl and metal ions, and the pH value of the equi-acidity point depends on the content of the surface hydroxyl and the complexation ability. Both δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 have abundant surface hydroxyl groups, but the pH values at the equi-acidity point are quite different. δ1-MnO2 is much higher than δ2-MnO2, indicating that δ2-MnO2 has a stronger surface hydroxyl complexing ability, so it is speculated that it has a greater adsorption potential. It can be seen from Figure 1 that the isoelectric points of δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 are 3.7 and 3.4, respectively. When the solution pH was lower than the equi-acidity point pH, the surface of MnO2 was positively charged. When the solution pH was higher than the equi-acidity point pH, the surface of MnO2 was negatively charged, and the heavy metal cations in the solution could be adsorbed by charge attraction.

Figure 1.

Surface zeta potential of δ-MnO2.

The two kinds of δ-MnO2 have a pore structure, and the average pore diameter is large. The pore volume and average pore diameter of δ2-MnO2 are higher than those of δ1-MnO2. It can be seen from Figure 2 that the adsorption and desorption isotherms of the two kinds of δ-MnO2 show the fourth type, and there is an obvious hysteresis loop. δ1-MnO2 belongs to the H1 hysteresis loop, which is caused by the difference in the regular shape of the pores and the size distribution of the narrow pores. The pore size distribution can be found to be mainly in the range of 2–10 nm. δ2-MnO2 belongs to the H3 type hysteresis loop, and the MnO2 is composed of disc-shaped particles. The pores are slit-shaped. It can be found from the pore size distribution that most of the pores are distributed in the range of 2–10 nm, and there are still some pores in the range of 10–100 nm. The macropore structure is more abundant than δ1-MnO2.

Figure 2.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption curve of δ-MnO2.

From Table 1 and the above analysis, the adsorption performance of δ2-MnO2 should be slightly better than that of δ1-MnO2. It can also be found from the study of Li et al. that the adsorption efficiency of δ2-MnO2 on cobalt and nickel is higher than that of δ1-MnO2. In this paper, based on the two δ-MnO2 adsorption conditions of Li et al.,53 20 g/L Mn2+ concentration and 10 g/L MnO2 addition were obtained as the better conditions. The optimal reaction time, reaction temperature, reaction pH, Co2+ concentration, and Ni2+ concentration were further explored; the adsorption efficiency of MnO2 for Co2+ and Ni2+ was determined; and the influence of process conditions on the adsorption performance of MnO2 was analyzed.

Table 1. Partial Performance Parameters of Two Kinds of δ-MnO2.

| MnO2 crystal form | specific surface area (m2/g) | equi-acidity points pH | isopotential point | aperture (nm) | pore volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ1-MnO2 | 217.42 | 3.85 | 3.7 | 5.2627 | 0.323685 |

| δ2-MnO2 | 223.46 | 1.40 | 3.4 | 8.5211 | 0.417930 |

2.1.1. Effect of Reaction Time

When the Co2+ concentration was 80 mg/L; the Ni2+ concentration was 80 mg/L; the reaction temperature was 80 °C; the reaction pH was 7; and the reaction time was 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 150 min, respectively, the adsorption rate of Co2+ and Ni2+ in manganese sulfate by δ-MnO2 was as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Effect of reaction time on the adsorption of Co2+ and Ni2+.

It can be seen from Figure 3 that with the increase of reaction time, the adsorption of δ-MnO2 on Co2+ and Ni2+ first increased and then decreased. When the reaction time was 60 min, the adsorption rate reached the highest. The adsorption reaction of the two kinds of δ-MnO2 in the first 30 min was faster due to the fact that the surface hydroxyl of δ-MnO2 adsorption sites have not been occupied. Co2+ and Ni2+ adsorption probability is the largest, the surface complex reaction is intense, and the solution pH decreased rapidly. When the reaction time was 30–60 min, the adsorption sites were gradually occupied, the complexation reaction decreased, the pH of the solution decreased slowly, the pH adjustment times were less, and the adsorption rate of Co2+ and Ni2+ slowed down. At 60 min, the adsorption amount reached saturation. At this time, the adsorption and desorption maintained a dynamic equilibrium. The pH of the solution no longer decreased and remained stable at about 7. The adsorption amounts of Co2+ and Ni2+ reached the maximum. After 60 min, the adsorption rate decreased due to the shedding of Co2+ and Ni2+ adsorbed in MnO2 pores and attracted by charge, and the ion exchange reaction between other ions and adsorbed Co2+ and Ni2+. So the appropriate reaction time was 60 min.

The adsorption rate of δ1-MnO2 is higher in 10 min, and that of δ2-MnO2 is higher in 10–60 min. The above phenomenon is due to the slit-like shape of the internal pores of δ2-MnO2, and the ion diffusion in the interlayer needs a longer time to diffuse to the corresponding adsorption point, so the adsorption rate is lower. After 10 min, the diffusion adsorption process is no longer a limitation of the adsorption rate.54 More binding sites will have a higher adsorption rate. δ2-MnO2 has larger specific surface area, pore size, and pore volume, which can provide more adsorption sites, so the adsorption rate is higher.

2.1.2. Effect of Temperature

When the Co2+ concentration was 80 mg/L; the Ni2+ concentration was 80 mg/L; the reaction time was 60 min; the reaction pH was controlled at 7; and the reaction temperature was 20, 35, 50, 65, 80, and 95 °C, respectively, the adsorption rate of Co2+ and Ni2+ in manganese sulfate by δ-MnO2 was as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Effect of temperature on the adsorption of Co2+ and Ni2+.

It can be seen from Figure4 that the adsorption rate of δ-MnO2 for Co2+ and Ni2+ increased with the increase of reaction temperature. Since the adsorption of δ-MnO2 was mainly due to the complexation reaction of surface hydroxyl, the higher the reaction temperature was, the more intense the movement of Co2+ and Ni2+ in the solution was, the higher the possibility of binding with hydroxyl was, and the faster the reaction was. When the temperature reached 80 °C, the adsorption rate was basically unchanged, the adsorption amount and desorption amount were in a dynamic equilibrium, and the adsorption of manganese dioxide reached saturation. It was of little significance to continue to increase the temperature. When the temperature was lower than 65 °C, the adsorption rate of δ1-MnO2 for the two ions was higher. When the temperature was higher than 65 °C, the adsorption rate of δ2-MnO2 for the two ions was higher, and δ2-MnO2 was more affected by temperature, indicating that, at lower temperatures, the slit pore structure of δ2-MnO2 limited the binding of Co2+ and Ni2+ with internal adsorption sites, and the adsorption rate of δ1-MnO2 with a regular pore structure was higher. At higher temperatures, Co2+ and Ni2+ were more active, and the adsorption rate of δ2-MnO2 with a larger pore volume was higher. Therefore, the increase of temperature is beneficial to the reaction, and the adsorption reaction belongs to the endothermic reaction, which is mainly affected by the surface hydroxyl complexation. There are differences in the adsorption rate of two kinds of δ-MnO2 with different pore structures and sizes.

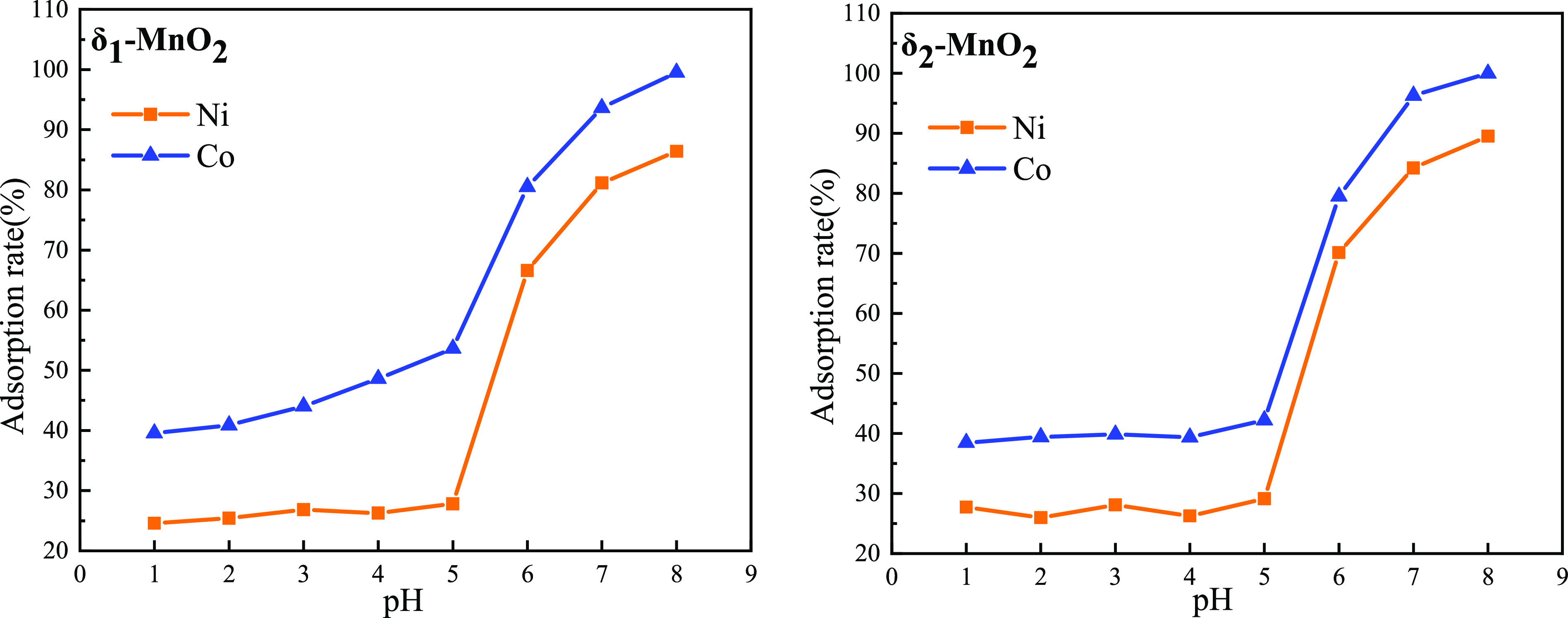

2.1.3. Effect of pH Value

When Co2+ concentration was 80 mg/L; Ni2+ concentration was 80 mg/L; reaction time was 60 min; reaction temperature was 80 °C; and reaction pH value was controlled at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, respectively, the adsorption rate of Co2+ and Ni2+ in manganese sulfate solution by δ-MnO2 was as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Effect of pH value on the adsorption of Co2+ and Ni2+.

It is obvious from Figure 5 that the adsorption rate of δ-MnO2 for Co2+ and Ni2+ increased with the increase of pH value of the manganese sulfate solution. The change trend of the adsorption rate of the two kinds of δ-MnO2 was similar. When the solution pH increased from 1 to 5, the adsorption rate of the two ions increased slowly, mainly because the concentration of H+ was high at low pH, and the surface hydroxyl was more likely to react with H+ to form ≡SOH2+. At the same time, the solution pH was less than the isoelectric point and the surface of δ-MnO2 was positively charged, so the adsorption of Co2+ and Ni2+ was mainly affected by the structural defects and voids of δ-MnO2. However, when pH increased from 5 to 8, the adsorption rate increased rapidly. When pH reached 8, the adsorption rates of Co2+ and Ni2+ by δ-MnO2 reached the highest. This was because the pH of the solution was obviously higher than the isoelectric point, the negative charge on the surface of MnO2 increased, the hydroxyl was deprotonated to form ≡SO–, and then it reacted with Co2+ and Ni2+ in the solution, so it was easier to adsorb Co2+ and Ni2+ in the solution. At the same time, when pH = 8, Mn2+ in manganese sulfate would be partially consumed and converted to Mn(OH)2. So the appropriate pH value was 7.

2.1.4. Effect of Co2+ and Ni2+ Concentration

When reaction time was 60 min; reaction temperature was 80 °C; pH value was controlled at 7; the concentration of Ni2+ was 100 mg/L; and the concentration of Co2+ was 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 mg/L, respectively, the effect of Co2+ concentration on the adsorption of Ni2+ in the manganese sulfate solution by δ-MnO2 was as shown in Figure 6a. When the other conditions were the same; the concentration of Co2+ was 100 mg/L; and the concentration of Ni2+ was 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 mg/L, respectively, the effect of Ni2+ concentration on the adsorption of Co2+ in the manganese sulfate solution by δ-MnO2 was as shown in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Interaction of cobalt and nickel ions. (a) Effect of Co2+ concentration on Ni2+ adsorption. (b) Effect of Ni2+ concentration on Co2+ adsorption.

Figure 6 shows that there is an obvious competitive relationship between Co2+ and Ni2+ in the adsorption process. The adsorption rate of Ni2+ decreases gradually with the increase of Co2+ concentration, and the adsorption rate of Co2+ decreases gradually with the increase of Ni2+ concentration. Co2+ is stronger in the adsorption competition. The affinity of hydroxyl to Co2+ is relatively large, and there is a difference in the adsorption capacities of two δ-MnO2 to two ions. δ1-MnO2 is more inclined to adsorb Ni2+, and δ2-MnO2 is more inclined to adsorb Co2+. The affinity and adsorption capacity of manganese dioxide for different metal ions are different. The adsorption order is generally Pb2+ > Cu2+ > Co2+ > Ni2+ > Zn2+ > Mn2+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+ > Na+, which is basically consistent with the order of ionic hydrolysis constants.53 This is also the reason why Co2+ is preferentially adsorbed and Co2+ and Ni2+ could be adsorbed in the manganese sulfate solution. Considering the adsorption efficiency and adsorption competition, Co2+ and Ni2+ were set at 80 g/L.

2.2. Study on the Adsorption Mechanism of MnO2

The optimal adsorption conditions were obtained through the above adsorption experiments, and they were as follows: the Co2+ concentration was 80 mg/L, Ni2+ concentration was 80 mg/L, reaction time was 60 min, reaction temperature was 80 °C, and pH value was 7. On this basis, products before and after adsorption were characterized by XRD, SEM, EDS surface scanning, IR, and XPS, and the adsorption mechanism of δ-MnO2 was analyzed in depth.

2.2.1. Phase

The XRD analysis of manganese dioxide before and after Co and Ni adsorption is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

XRD patterns of δ-MnO2 before and after adsorption.

According to the XRD pattern analysis, Mn3O4 and MnOOH both appear in manganese dioxide after adsorption under the above conditions. This is because the adsorption process is affected by acid points of MnO2, and the pH could be stabilized only by repeatedly adjusting the pH. In this process, a small amount of Mn2+ in the MnSO4 solution became Mn(OH)2 at pH = 7. Mn(OH)2 was oxidized by oxygen to MnOOH in the air, and some MnOOH was further oxidized to Mn3O4. These two substances were filtered out together in the adsorbed product, so they appeared in the phase.

2.2.2. Microstructure and Surface Elements

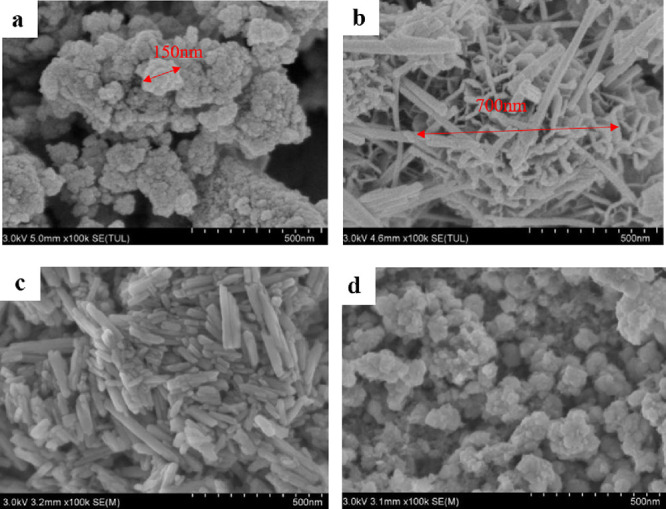

The SEM images of manganese dioxide before and after Co and Ni adsorption are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

SEM images before and after adsorption: (a) δ1-MnO2 before adsorption, (b) δ2-MnO2 before adsorption, (c) δ1-MnO2 after adsorption, and (d) δ2-MnO2 after adsorption.

As shown in Figure 8, δ1-MnO2 before adsorption is stacked by nanoparticles with a diameter of 150 nm, forming a cluster of layered structures with large voids. The morphology after adsorption is shown in Figure 8c, which changes from the large pore structure of nanoparticles before adsorption to the dense structure of nanorods with different lengths. The δ2-MnO2 before adsorption is aggregated by nanorods and has a rich pore structure with a diameter of 700 nm. δ2-MnO2 after adsorption transforms into a compact accumulation structure. The large difference in morphology depends on several reasons. First, the surface hydroxyl of MnO2 combines with a large number of Mn2+, Co2+, and Ni2+ in the solution to form a new morphology structure. Second, it could be known that Mn3O4 and MnOOH produced in the adsorption process also affected the microstructure of MnO2. Finally, the porous structure of MnO2 is occupied by metal ions after adsorption to form a relatively dense structure.

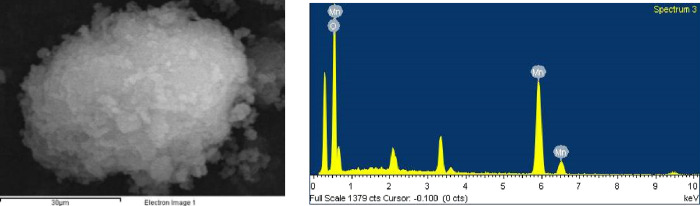

EDS diagrams of two kinds of δ-MnO2 before adsorption are shown in Figures 9 and 10. The higher the O/Mn ratio of MnO2 is, the richer the surface oxygen is, and the oxygen coordination around the manganese vacancy is unsaturated, resulting in the formation of a large number of hydroxyl groups on the surface of MnO2, which is more conducive to the surface complexation reaction. The O/Mn ratios of δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 are 2.76 and 2.65, respectively, which indicate that the two kinds of δ-MnO2 have a high surface oxygen content and could form more hydroxyl functional groups on their surfaces, so they have the potential to become adsorbents with a high adsorption capacity.

Figure 9.

EDS point scan diagram of δ1-MnO2.

Figure 10.

EDS point scan diagram of δ2-MnO2.

It can be seen from Figure 11 that Mn and O in the products adsorbed by δ1-MnO2 are still the main two elements, and a large number of Co2+ and Ni2+ are distributed, indicating that Co2+ and Ni2+ are adsorbed by MnO2. At the same time, it can be seen that there is still O element distribution in the area without Mn element. This part of oxygen may come from the crystal water formed by MnO2 adsorbed water. According to the distribution of Co2+ and Ni2+ elements, it is speculated that it may also come from the oxides of Co and Ni. It can be seen from Table 1 that the O/Mn ratio of δ1-MnO2 increased from 2.76 to 3.11 after adsorption. In the process of surface hydroxyl binding to metal ions, with the progress of complexation reaction, O element was increasing. According to ≡SO– + M2+ + H2O≡SOMnOH + H+, surface hydroxyl ≡SOH reacted with metal ions M to form ≡SOMOH. The second sources of oxygen are crystal water produced during adsorption and manganese oxide in the solution. Co2+ and Ni2+ ions are mainly distributed on the surface of MnO2 particles, and a small amount of them is evenly distributed in the gap of MnO2 particles. It further shows that the hydroxyl complexation reaction on the surface of MnO2 plays a leading role in the adsorption of Co2+ and Ni2+, and MnO2 pores play an auxiliary role. At the same time, the proportion of the Co element is slightly higher than that of the Ni element. The K ions in the adsorbed δ1-MnO2 almost do not exist, and the layered structure of δ-MnO2 is mainly supported by K ions. The behavior of other metal ions replacing K ions is bound to affect the structure of δ-MnO2 in the adsorption process.

Figure 11.

EDS surface scan diagram of δ1-MnO2 after adsorption.

Figure 12 shows that the distribution of each element in the adsorption products of δ2-MnO2 and δ1-MnO2 is basically consistent. The only difference is that there is a K element in the adsorption products of δ2-MnO2, indicating that the stability of the δ2-MnO2 layered structure is stronger. According to Table 2, the O/Mn ratio of δ2-MnO2 increased from 2.65 to 2.90. And the element proportion of Co2+ and Ni2+ shows that the adsorption capacity of δ2-MnO2 for Co2+ is slightly higher than that of δ1-MnO2 and that the adsorption capacity of δ1-MnO2 for Ni2+ is slightly higher than that of δ2-MnO2.

Figure 12.

EDS surface scan diagram of δ2-MnO2 after adsorption.

Table 2. The Proportion of Each Element after the Adsorption of Two Kinds of δ-MnO2.

| δ-MnO2 | element | Mn | O | Ni | Co | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ1-MnO2 | percentage by weight | 50.33 | 45.63 | 1.87 | 2.17 | 0 |

| atomic percent ratio | 23.87 | 74.34 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0 | |

| δ2-MnO2 | percentage by weight | 51.66 | 43.67 | 1.67 | 2.40 | 0.59 |

| atomic percent ratio | 25.05 | 72.71 | 0.76 | 1.09 | 0.40 |

2.2.3. Surface Hydroxyl and Other Groups

The infrared spectral characteristics of manganese dioxide before and after Co and Ni adsorption are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

FT-IR spectra of δ-MnO2 before and after adsorption.

In the δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 before adsorption, there are a surface hydroxyl stretching vibration peak near 3400 cm–1, surface hydroxyl bending vibration peak near 1600 and 1100 cm–1, and Mn–O lattice vibration peak near 500–600 cm–1. In addition, there are acetate ion C–O and C–H vibration peaks near 1400 cm–1 in δ1-MnO2 prepared by manganese acetate. δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 have broad and strong hydroxyl vibration peaks, So they are rich in surface hydroxyl, which is more conducive to surface complexation reaction with heavy metal ions so as to achieve an excellent adsorption effect.

In the δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 after adsorption, the surface hydroxyl vibration peaks near 3400 and 1600 cm–1 are obviously weakened, indicating that a large number of hydroxyls are bound to metal ions, and the utilization rate of hydroxyls is greatly increased. There are new vibration peaks that appeared near 2600 and 2000 cm–1, which are likely to be ≡SOCoOH and ≡SONiOH formed by the complexation of Co2+, Ni2+, and hydroxyl groups on the surface of δ-MnO2. The enhancement of the vibration peak near 1000 cm–1 is caused by the increase of adsorbed water on the surface of δ-MnO2, which is basically consistent with the EDS surface oxygen scanning analysis. The vibration peaks of the Mn-O lattice near 500–600 cm–1 moved and were enhanced, which are caused by Mn2+ adsorption on the δ-MnO2 surface or Mn3O4 and MnOOH generated from Mn2+.

2.2.4. Atomic Valence State

The XPS spectra of manganese dioxide before and after Co and Ni adsorption are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

XPS spectra of δ-MnO2 before and after adsorption: (a) full spectrum, (b) O1s spectrum, (c) Mn2p spectrum, (d) Ni2p spectrum, and (e) Co2p spectrum.

From Figure 14a, it could be found that the K+ peak basically disappeared in δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 after adsorption. It indicates that interlayer K+ was replaced by metal cations in the solution. Figure 14b shows that the structure oxygen of δ-MnO2 has no obvious change after adsorption, but the proportion of adsorbed oxygen increases greatly. This indicates that in the adsorption process of surface hydroxyl, the surface hydroxyl reacts with metal ions (M) to form ≡SOMOH. The oxygen in ≡SOMOH causes the increase of adsorbed oxygen on the surface of δ-MnO2. Therefore, the adsorbed oxygen content increases with the adsorption. It could be seen from Figure 14c that the peak bond energy of Mn2p decreased after adsorption, indicating that the proportion of low-valent Mn increased, which was related to Mn2+ adsorbed by MnO2 and the Mn3O4 and MnOOH generated during the adsorption process. Figure 14d,e could also verify that Co2+ and Ni2+ were adsorbed by MnO2, but the adsorption amounts of Co2+ and Ni2+ were relatively small compared with the adsorbent body, so the 2p peak was not obvious. It could be speculated that the combined valence of Co and Ni was bivalent according to the binding energy.

2.2.5. Adsorption Mechanism

According to the above research, the mechanism of manganese dioxide adsorbing Co and Ni ions is as follows. The protonation and deprotonation of surface hydroxyl (≡SOH) occurred first when MnO2 was in contact with solution.53,55 The reaction formulas are shown in formula 1 and formula 2.

| 1 |

| 2 |

The hydroxyl group underwent deprotonation reaction to form ≡SO– and then complexed with Co2+ and Ni2+ in the solution. The reaction formulas are shown in formula 4 and formula 5.

| 3 |

| 4 |

Due to the difference in the complexing ability of hydroxyl groups on the surface of MnO2 to different cations, there would be an ion exchange reaction on the surface of δ-MnO2. For example, the K+ supporting the layered structure was replaced by metal ions, and a large number of Mn2+, Co2+, and Ni2+ entered the macropore structure of MnO2, resulting in the change of its microstructure. The complex reaction produced ≡SOCo+ and SONi+, so Co and Ni appeared on the surface element distribution of δ-MnO2 after adsorption. A large number of surface hydroxyl groups of MnO2 combined with metal ions, and the utilization rate of hydroxyl groups increased, resulting in the weakening of hydroxyl vibration peak. The surface hydroxyl group reacted with metal ions (M) to form ≡SOMOH. The oxygen in ≡SOMOH still only existed on the surface of MnO2 in the form of adsorbed oxygen. Therefore, the adsorbed oxygen content increased with the adsorption. After the complexation reaction, Co2+ and Ni2+ appeared on the surface of MnO2, Mn2+ was also adsorbed by MnO2, and Mn3O4 and MnOOH were produced during the adsorption process, which would increase the proportion of low-valence Mn.

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Materials and Equipment

Sulfuric acid, ammonia, potassium permanganate, manganese acetate, manganese sulfate monohydrate, nickel sulfate hexahydrate, and cobalt sulfate heptahydrate used in the experiment were all analytically pure reagents and produced by Tianjin Comitry Co., Ltd.

The experimental equipment used was as follows: the PHS-25 digital pH meter was produced by Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd.; the HH-3 constant-temperature water bath boiler was produced by Shanghai Scientific Analysis Experimental Instruments Co., Ltd.; the DHG-905A constant-temperature drying box was produced by Beijing Yongguangming Medical Instruments Co., Ltd.; the P4Z vacuum pump was produced by Beijing Jinghui Kaiye Co., Ltd.; the PL2002 electronic analysis balance was produced by Mettler-Toledo Instruments (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.; the JJ-1 precision booster electric stirrer was produced by Changzhou Aohua Instruments Co., Ltd.; the SHA-C constant-temperature water bath shaker reciprocating oscillator was produced by Changzhou Guohua Electric Co., Ltd.; the SX-4-10 box resistance furnace was produced by Tianjin Tate Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd.; the HY-5B rotary oscillator was produced by Changzhou Langyue Instruments Manufacturing Co., Ltd.; and the A3AFG-13 flame atomic absorption spectrometer was produced by Beijing Pusan General Instrument Co., Ltd.

3.2. Experimental Process

The synthesis steps of δ1-MnO2 are as follows: 0.1 mol/L potassium permanganate solution 300 mL and 0.15 mol/L manganese acetate solution 150 mL were prepared with deionized water, respectively. The potassium permanganate solution was first stirred by magnetic force for 30 min, and then the prepared concentration of manganese acetate solution was added. The stirring reaction was carried out at 80 °C for 6 h. After the solution was cooled to room temperature, the black precipitate was obtained. The product was washed with deionized water many times, and the impurity ions were removed. The product was dried at 100 °C for 5 h.

The steps of synthesizing δ2-MnO2 are as follows: 0.1 mol/L potassium permanganate solution 300 mL and 0.15 mol/L manganese sulfate solution 150 mL were prepared with deionized water, respectively. The potassium permanganate solution was first stirred by magnetic force for 30 min, and then the prepared concentration of MnSO4 solution was added. The magnetic stirring reaction was carried out at 80 °C for 6 h. After the solution was cooled to room temperature, the brown and black precipitate was obtained. The product was washed with deionized water many times, and the impurity ions were removed. The product was dried at 100 °C for 5 h.

A mixed solution of Mn2+, Ni2+, and Co2+ was prepared with manganese sulfate monohydrate, nickel sulfate hexahydrate, cobalt sulfate heptahydrate, and deionized water. The pH of the solution was adjusted with 10% ammonia, and a certain amount of prepared δ-MnO2 was added. The solution was continuously stirred in a constant-temperature water bath at a certain temperature. Due to the influence of the pH of MnO2 equi-acidity point, the pH of the solution would decrease to a certain value. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 by dropping ammonia. With the progress of the reaction, the pH of the solution decreased again and continued to be adjusted until the pH did not decrease. The adsorption experiments were carried out by controlling the reaction time, reaction temperature, reaction pH, MnO2 addition, Mn2+ concentration, Co2+ concentration, and Ni2+ concentration. After the adsorption, the solution was quickly filtered. The concentrations of Ni2+ and Co2+ in the filtrate were determined by an A3AFG-13 flame atomic absorption spectrometer, and the filter residue was further characterized and analyzed after drying.

3.3. Characterization Methods

The adsorption rate formula is shown in formula 5:

| 5 |

c0 is the initial concentration of impurity ions before adsorption, and c is the concentration of impurity ions after adsorption.

In the experiment, the phase identification was done by a Bruker D8 ADVANCE diffraction analyzer from Bruker, Germany. The microstructure and energy spectrum were analyzed by an SU8020 scanning electron microscope from Hitachi, Japan. The FT-IR analysis was collected on a Nicolet iS10 infrared spectrometer produced by Nigaoli, USA. The XPS data were collected on a Thermo ESCALAB 250Xi electronic energy spectrometer produced by ThermoFisher Scientific, USA.

4. Conclusions

Two kinds of δ-MnO2 were prepared under controlled conditions. With δ-MnO2 addition amount of 10 g/L, Co2+ and Ni2+ in the manganese sulfate solution with Mn2+ concentration of 20 g/L were adsorbed and removed, and better adsorption conditions were obtained. They were as follows: When Co2+ concentration was 80 mg/L, Ni2+ concentration was 80 mg/L, reaction time was 60 min, reaction temperature was 80 °C, and pH value was 7, the adsorption rate of Co2+ and Ni2+ by the two kinds of δ-MnO2 reached more than 80%. The phase, microstructure, surface hydroxyl, surface element content, and surface oxygen of the δ-MnO2 were analyzed after adsorption. MnOOH phase was found in both kinds of δ-MnO2 after adsorption. δ1-MnO2 and δ2-MnO2 showed dense rod-like structures with different lengths and flake-like structures of fine particles. Co and Ni were distributed on the surface and gap of MnO2 particles after adsorption, the atomic percentage of Co was slightly higher than that of Ni, and the oxygen content would increase after adsorption. After adsorption, the surface hydroxyl vibration peaks of δ-MnO2 decreased, and new vibration peaks appeared near 2668.32, 1401.00, and 2052.19 cm–1, indicating that cations such as Co2+ and Ni2+ complexed with hydroxyl and new vibration peaks were formed on the surface of δ-MnO2. After adsorption, partial Co2+ and Ni2+ appeared on the surface of δ-MnO2, and the surface oxygen increased. The adsorption mechanism of manganese dioxide is revealed, as follows: δ-MnO2 reacted with metal ions (M) to form ≡SOMOH through surface hydroxyl groups so as to realize the adsorption and removal of Co2+ and Ni2+ in the manganese sulfate solution.

Acknowledgments

The funding supports for this study were obtained from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51864012), Guizhou Provincial Science Cooperation Program ([2016] 5302, [2017] 5788, [2018] 5781, [2019] 1411, [2019] 2841, [2022] 020, and [2022] 003), and Major special projects in Tongren City, Guizhou Province (2021) 13. The authors sincerely thank the reviewers for their views and suggestions to further improve the quality of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

# P.Y. and J.W.W. contributed equally to this work

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Liu Y.; Ming X. Q.; Huang B. H.; Liu H. H.; Yuan M. L. Control of Fluorine Content in High Purity Manganese Sulfate Prepared By Fluorination. Min. Metall. Eng. 2021, 41, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- He Y. H.; Zhang H. J.; Xiong S. MnSO4 solution and preparation of battery grade high purity manganese sulfate. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 38, 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. H.; Wu R. L.; Hu P. Study on impurity characteristics and purification process of high purity manganese sulfate. World Nonferrous Metals 2020, 1, 186–188. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. H.; Feng H. C.; Luo Y. Y.; Lei J.; Huang X. Determination of silicon content in manganese sulfate for battery and battery materials. Shanxi Chemical Industry 2021, 41, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- He B. H. Experimental study on removal of heavy metals from industrial manganese sulfate. China Manganese Industry 2021, 39, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Huang P.; Li C. Flexible and self-supported manganese dioxide/S composite cathode for high electrochemical performance. Ionics 2021, 27, 5037–5042. 10.1007/s11581-021-04260-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parveen N.; Ansari S. A.; Al-Arjan W. S.; Ansari M. O. Manganese dioxide coupled with hollow carbon nanofiber toward high-performance electrochemical supercapacitive electrode materials. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices 2021, 6, 472–482. 10.1016/j.jsamd.2021.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi F.; Javanbakht M.; Shahrokhian S. Anodic pulse electrodeposition of mesoporous manganese dioxide nanostructures for high performance supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 887, 161376. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.161376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S.; Ahmad Z.; Kumar A.; Rafiq M.; Vashistha V. K.; Ashiq M. N.; Kumar A. Effective removal of methylene blue using nanoscale manganese oxide rods and sphere derived from different precursors of manganese. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 155, 110121. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D. J.; Wang H. F.; Gou B. B.; Li M. D.; Wang J. W. Preparation of Octahedral Mn3O4 by Liquid Phase Method. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2022, 2166, 012067. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Song D.; Zhang Q.; Huang X. P. Evaporation-Cooling Coupling Method to Remove the Calcium and Magnesium Impurities in Leaching Solution of Manganese Ore. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 651, 042055 10.1088/1755-1315/651/4/042055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. J.; Wang W. N.; Liu Y. L.; Liu F.; Chen X. Y. Removal of Heavy Metals from Manganese Sulfate Solution and Preparation Battery-level Manganese Sulfate. Nonferrous Metals (Extractive Metallurgy) 2020, 11, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tian J. Y.; Wang H. F.; Kuang S. D.; Yang Q. K.; Hu P.; Wang J. W. Study on Removal of Heavy Metals from Manganese Sulfate Solution by Sulfide. Nonferrous Metals (Extractive Metallurgy) 2019, 12, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. Z. Experimental Study on Purification of Cadmium from Manganese Sulfate Solution by Manganese Sulfide. China Steel Focus 2020, 11, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q. Q.; Gu G. H.; Wang H. Separation of Manganese from calcium and magnesium in sulfate solutions via carbonate precipitation. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1118–1125. 10.1016/S1003-6326(16)64210-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.; Qiu Y. R. Preparation of electronic grade Manganese sulfate from leaching solution of ferromanganese slag. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2014, 24, 3716–3721. 10.1016/S1003-6326(14)63520-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He G. X.; He L. H.; Zhao Z. W. Thermodynamic study on phosphorus removal from tungstate solution via magnesium salt precipitation method. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 3440–3447. 10.1016/S1003-6326(13)62886-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. L.; Wang H. F.; Wang J. W.; Zhao P. Y. Removal of Cobalt and Nickel from Manganese Sulfate Leachate by Carbonization. Conservation and Utilization of Mineral Resources 2020, 40, 103–107. 10.13779/j.cnki.issn1001-0076.2020.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. L.; Wang H. F.; Wang J. W. Removal of Calcium and Magnesium from Manganese Sulfate Leaching Solution via a Reverse Precipitation by Carbonation. Kuangye Gongcheng (Changsha, China) 2020, 40, 82–85+93. [Google Scholar]

- Jantunen N.; Kauppinen T.; Salminen J.; Virolainen S.; Lassi U.; Sainio T. Separation of zinc and iron from secondary manganese sulfate leachate by solvent extraction. Miner. Eng. 2021, 173, 107200. 10.1016/j.mineng.2021.107200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Y.; Wang K. T.; Ming X. Q.; Zhan F.; Muhammad Y.; Zhan Y. Z.; Wei W. J.; Li H. Q. The Efficient Removal of Calcium and Magnesium Ions from Industrial Manganese Sulfate Solution through the Integrated Application of Concentrated Sulfuric Acid and Ethanol. Metals 2021, 11, 1339. 10.3390/met11091339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. F.; You X. Y.; Tian J. Y.; Chen X. L.; Wang J. W. Solubility and crystallinity of manganese, magnesium and ammonium double salt systems. Mater. Express 2021, 11, 540–550. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. S.; Hu X.; Li T. X.; Zhang Y. X.; Xu H. X.; Sun Y. Y.; Gu X. Y.; Gu C.; Luo J.; Gao B. MIL series of metal organic frameworks (MOFs) as novel adsorbents for heavy metals in water: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128271. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P.; Huang Z. B.; Ma Q.; Zhang B. L.; Wang P. Artificial humic acid synthesized from food wastes: An efficient and recyclable adsorbent of Pb (II) and Cd (II) from aqueous solution. Environ. Technol. Innovation 2022, 27, 102399. 10.1016/j.eti.2022.102399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ihsanullah I. Applications of MOFs as adsorbents in water purification: Progress, challenges and outlook. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2022, 26, 100335. 10.1016/j.coesh.2022.100335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur A. K.; Singh R.; Teja P. R.; Pundir V. Green adsorbents for the removal of heavy metals from Wastewater: A review. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 57, 1468–1472. 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaimee M. Z. A.; Sarjadi M. S.; Rahman M. L. Heavy Metals Removal from Water by Efficient Adsorbents. Water 2021, 13, 2659. 10.3390/w13192659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egorova A. A.; Bushkova T. M.; Kolesnik I. V.; Yapryntsev A. D.; Kottsov S. Y.; Baranchikov A. E. Selective Synthesis of Manganese Dioxide Polymorphs by the Hydrothermal Treatment of Aqueous KMnO4 Solutions. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 66, 146–152. 10.1134/S0036023621020066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. P.; Zhao Q. Y.; Wang C. Removal of heavy metal ions by manganese dioxide-based nanomaterials and mechanism research: A review. Environ. Chem. 2020, 39, 687–703. [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z. H.; He S. F.; Han C. Y.; Zhang L. Y.; Luo Y. M. Progress of Research onTreatment of Heavy Metal Wastewater by Adsorption. Environ. Prot. Sci. 2010, 36, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Meng K. Y.; Wu X. W.; Zhang X. Y.; Su S. M.; Huang Z. H.; Min X.; Liu Y. G.; Fang M. H. Efficient Adsorption of the Cd(II) and As(V) Using Novel Adsorbent Ferrihydrite/Manganese Dioxide Composites. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 18627–18636. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneechakr P.; Mongkollertlop S. Investigation on adsorption behaviors of heavy metal ions (Cd2+, Cr3+, Hg2+ and Pb2+) through low-cost/active manganese dioxide-modified magnetic biochar derived from palm kernel cake residue. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104467. 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W. Q.; Lv R. W.; Tao Q. Q. Facile Preparation of Novel Manganese Dioxide Modified Nanofiber and Its Uranium Adsorption Performance. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 2021, 09, 1837–1852. 10.4236/jamp.2021.97118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M. M.; Yao C. X.; Su Y.; Liu J. L.; Xu L. J.; Hou S. F. Synthesis of membrane-type graphene oxide immobilized manganese dioxide adsorbent and its adsorption behavior for lithium ion. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130487. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. P.; Xu F. F.; Xue J. Y.; Chen S. Y.; Wang J. J.; Yang Y. J. Enhanced removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution using manganese dioxide-loaded biochar: Behavior and mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6067. 10.1038/s41598-020-63000-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R. J.; Fan Y. Y.; Ye R. Q.; Tang Y. X.; Cao X. H.; Yin Z. Y.; Zeng Z. Y. MnO2-Based Materials for Environmental Applications. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004862. 10.1002/adma.202004862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. H.; Liu X. Y.; Deng T. Q.; Huang S. Z.; Ding M.; Miao X. H.; Zhu C. Z.; Zhu Y. H.; Liu W. X.; Wu F. F.; Gao C. J.; Yang S. W.; Yang H. Y.; Shen J. N.; Cao X. H. Enabling Superior Sodium Capture for Efficient Water Desalination by a Tubular Polyaniline Decorated with Prussian Blue Nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. 2021, 32, 1907404. 10.1002/adma.201907404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. H.Study on adsorption effects of different crystalline MnO2 adsorbents on thallium and antimony in water. Xi’an Polytechnic University 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kong L. G.; Zhu Z. L.. Adsorption of several heavy metal ions in micro-polluted water by δ-MnO2. China Sustainable Development Forum 2006[C]. 2006. in Chinese

- Kanungo S. B.; Tripathy S. S.; Mishra S.; et al. Adsorption of Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ onto amorphous hydrous manganese dioxide from simple (1-1) electrolyte solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 269, 11–21. 10.1016/j.jcis.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscarson D. W.; Huang P. M.; et al. Kinetics of oxidation of arsenite by various manganesedioxides. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1983, 47, 644–648. 10.2136/sssaj1983.03615995004700040007x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Ye Z. J. The study on adsorption of As(III) from wastewater by different types of MnO2. China Environ. Sci. 1998, 2, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li S.Research on Adsorption Efficiency of Nickle Ion by Synthetic Manganese Oxides; Chongqing University, 2015. in Chinese [Google Scholar]

- Yao L.N.Arsenic Adsorption Performance of Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles. Qinghai Institute of Salt Lakes, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2018. in Chinese [Google Scholar]

- Xia W. T.; Zhao Z. W.; Ren Z. D. A Exploratory Researchondeep Removal Trace Molybdenum from Manganese Sulfate Solution with Powder Electrolytic Manganese Dioxide. China’s Manganese Industry 2008, 04, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xia W. T.; Zhao Z. W.; Chen A. L. Research on chemical manganese dioxide adsorbent for removing molybdenum from manganese sulfate solution. Chin. Battery Ind. 2008, 13, 363–366. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. L.; Wang H. F.; Wang J. W. Experimental Study on the Removal of Molybdenum from Manganese Sulfate Solution with Electrolytic Manganese Anode Slag. Metal Mine 2021, 05, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. F.; Chen X. L.; Zhao P. Y.; Gao Z. W.; You X. Y.; Tian J. Y.; Wang J. W. Preparation of New Nano-MnO2 and Its Molybdenum Adsorption in Manganese Sulfate Solution. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2020, 12, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Xue W. L.; Yi H.; Lu Y. L.; Xia L.; Meng D. L.; Song S. X.; Li Y. T.; Wu L.; Farías M. E. Combined electrosorption and chemisorption of As(III) in aqueous solutions with manganese dioxide as the electrode. Environ. Technol. Innovation 2021, 24, 101832. 10.1016/j.eti.2021.101832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. W.; Chen W.; Huang M.; Tang H. Y.; Zhang J.; Wang G.; Wang R. L. Metal organic frameworks derived manganese dioxide catalyst with abundant chemisorbed oxygen and defects for the efficient removal of gaseous formaldehyde at room temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 565, 150445. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.150445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christian F. B.; Oliver S. F.; Jordan B.; Manuel B.; Harald G.; Kai P. B.; Hans M.; Henning D. B. Revealing the Local pH Value Changes of Acidic Aqueous Zinc Ion Batteries with a Manganese Dioxide Electrode during Cycling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 020545. [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. The relation between chemical, physical properties and electrochemical activity form anganese dioxides(8). Battery Bimon. 2007, 04, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Li M. D.; Wang J. W.; Gou B. B.; Fu D. J.; Wang H. F.; Zhao P. Y. Relationship between Surface Hydroxyl Complexation and Equi-Acidity Point pH of MnO2 and Its Adsorption for Co2+ and Ni2+.ACS. Omega 2022, 7, 9602–9613. 10.1021/acsomega.1c06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.P.Adsorptive Removal of Lead Ions from Aqueous Solution Using Manganese Oxides Materials. Nanjing University, 2017, in Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Hiroki T.; Tatsuya O.; Masaichi N.; Ryusaburo F. Acid-Base Dissociation of Surface Hydroxyl Groups on Manganese Dioxide in Aqueous Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 136, 2782. [Google Scholar]