Abstract

Alkene aminoarylation with arylsulfonylacetamides via a visible-light mediated radical Smiles-Truce rearrangement represents a convenient approach to the privileged arylethylamine pharmacaphore traditionally generated by circuitous, multi-step sequences. Herein, we report detailed synthetic, spectroscopic, kinetic, and computational studies designed to interrogate the proposed mechanism, including the key aryl transfer event. The data are consistent with a rate-limiting 1,4-aryl migration occurring either via a stepwise process involving a radical Meisenheimer-like intermediate or in a concerted fashion dependent on both arene electronics and alkene sterics. Our efforts to probe the mechanism have significantly expanded the substrate scope of the transformation with respect to the migrating aryl group and provide further credence to the synthetic potential of radical aryl migrations.

Keywords: Photoredox, aminoarylation, radical cation, nucleophilic aromatic substitution, aryl transfer

Graphical Abstarct

Introduction

The arylethylamine scaffold is a pharmacophore noted for its prevalence in many anti-depressants along with endogenous neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin.1–3 The interaction of the core structure with various opioid receptors has led to the development of arylethylamine opioid addiction treatment therapies such as Suboxone.4 To date, access to this privileged core has relied on amino acid decarboxylation,5 reductive amination,6 benzyl cyanide hydrogenation,7 or nitro styrene reduction.8–11 In light of the current opioid epidemic, strategies to utilize a greater diversity of aryl and amine precursors are desirable in order to expand arylethylamine drug development.12,13 Relative to the aforementioned traditional synthetic strategies listed above, an intermolecular alkene aminoarylation is a more modular reaction design, enabling the synthesis of increasingly complex scaffolds from separate aryl, amino, and alkene precursors. Step-economy and amenability to catalysis are additional benefits to alkene aminoarylation from a synthetic standpoint.14

To this end, transition metal-catalyzed alkene aminoarylations (Pd and Rh) or aryl alkene difunctionalizations (Fe) have constituted important developments in strategies towards arylethylamines.15–19 Despite advancements, some transition-metal catalyzed methodologies necessitate directing groups, high-temperatures, or highly-engineered substrates to achieve the desired transformation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selected modern strategies for arylethylamine synthesis. Clockwise from the top: refs. 30, 26 & 27, 29, 31, 34, 16, 45, and 15 (top). Arylethylamine pharmaceuticals (middle). Key insights disclosed within this work (bottom).

Photoredox catalysis has emerged as an attractive alternative for arylethylamine synthesis and nitrogen functional group installation due to its obviation of many of the difficulties associated with transition metal-catalyzed methodologies. Nicewicz,20 Knowles,21–25 Jui26,27, Molander28,29, Reiser30, and Greaney31,32 have exploited a wide variety of simple nitrogen group precursors in the design of diverse, rapid, and versatile approaches to valuable nitrogen-containing scaffolds. The cited examples all highlight the ability of photoredox catalysis to generate radical intermediates which may be leveraged for their unique reactivity to enable innovative retrosynthetic disconnections.33 Furthermore, these reactions are generally carried out under mild conditions utilizing inexpensive, synthetically accessible precursors (Figure 1).

Recently, we demonstrated a visible light-mediated, intermolecular alkene aminoarylation featuring bifunctional arylsufonylacetamides as both the aryl and nitrogen group precursor.34 The method was developed based upon insights gleaned from our previous investigations of the Smiles-Truce rearrangement.35,36 Classically, this rearrangement is triggered by generation of a carbanion followed by an intramolecular nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr).37–39 It has been expanded to include a variety of ipso-substitution reactions with aryl sulfides, sulfoxides, sulfones, amides, amines, and ethers.40,41 Radical variants of the reaction were pioneered by Speckamp and Loven,42 while Tada43 realized its potential in arylethylamine synthesis using classical radical generation methods.

Seeking to avoid the use of stochiometric tin radical initiators and tethered substrates, we envisioned that under oxidative photoredox conditions, arylsulfonylacetamides and alkenes could react to form a carbon-centered radical predisposed to undergo the desired Smiles-Truce rearrangement. In our initial report, a variety of polycyclic and heteroarylsulfonylacetamides were successfully transformed to 2,2’-diarylethylamine scaffolds in a highly diastereoselective manner (Figure 1). The intermolecular design of our approach is another synthetic benefit, even in contrast to other photochemical methods.

Several mechanistic questions emerged from our initial study. First among them was the manner in which the key benzyl radical which undergoes the Smiles-Truce rearrangement is formed. Previous mechanistic studies had suggested sulfonylacetamide interception of an alkene radical cation (Figure 2 top), but had not ruled out the possibility of initial formation of the sulfonamidyl radical via a multisite concerted proton-electron transfer (MS-CPET) process similar to that studied by Knowles,24 followed by addition to an alkene (Figure 2, bottom). Second was whether the radical Smiles-Truce rearrangement was a stepwise or concerted process. Historically, ionic equivalents of these reactions have been thought to proceed via a stepwise SNAr mechanism with paradigmatic Meisenheimer intermediates.44,45 However, concerted processes allow for SNAr reactivity in substrates that would otherwise lead to prohibitively high energy intermediates. In fact, more recent theoretical and experimental investigations of the Smiles-Truce rearrangement for a variety of different substrate classes have provided evidence that both mechanistic pathways operate.46 Related to the foregoing, the third question was whether rearomatization occurred along with desulfonylation to yield the amidyl radical or whether a stabilized sulfonyl radical was formed as an intermediate.47 Clear discrimination between these intermediates and the manner in which they gave the desired amide product was left unclear in our preliminary disclosure. Lastly, we sought to understand the origins of the high observed diastereoselectivity >20:1 in favor of the syn-aminoarylation product. We hoped that the answers to these mechanistic questions would enable expansion of the scope of the methodology in both the alkene and aryl substrates and inspire future Smiles-Truce methodology development. Furthermore, our findings should enrich and inform further research into the vibrant fields of alkene difunctionalization and radical aryl transfer methodologies.48

Figure 2.

Key mechanistic questions addressed in this work.

In this report, we disclose a unified computational and experimental mechanistic investigation of our previously reported alkene aminoarylation methodology. Some of the primary developments include the discernment of arylsulfonylacetamide conjugate base addition to an alkene radical cation over competing hypotheses for the initial C–N bond formation step; a nuanced description of diastereoselective stepwise and concerted aryl transfer pathways; and the expansion of the methodology to include a broader range of alkene and arylsulfonylacetamides, most notably unactivated benzenesulfonylacetamides. The broader scope provides access to a wider array of aminoarylation products not achieved in our previous report and corroborates several key computational findings with respect to the barrier to 1,4-aryl transfer in the transformation.

Results and Discussion

A. Mechanism of Benzylic Radical Formation

Stern-Volmer quenching experiments in our initial report suggested formation of an alkene radical cation which was intercepted by either the sulfonylacetamide or its conjugate base (Figure 3A/A’) to yield the key benzylic radical.49 However, neither oxidation of the conjugate base of the sulfonylacetamide in a sequential proton loss electron-transfer fashion (SPLET, Figure 3B) nor multisite concerted proton-electron transfer (MS-CPET) from the H-bonded sulfonylacetamide followed by N-radical addition onto the alkene (Figure 3D) had been ruled out. Several examples of MS-CPET mechanisms for the formation of amidyl and sulfonamidyl radicals have been recently reported by the Knowles lab.22,24 To provide insight on the relative likelihood of these possibilities, we calculated the ionization potentials of the acetylsulfonamide and its conjugate base and compared them to those of our typical alkene substrate (trans-anethole, 2a). Furthermore, we considered the free energy changes for subsequent reactions leading to the key benzylic radical intermediate (Figure 3). Although capture of the sulfonylacetamidyl radical by the alkene is the most thermodynamically favourable pathway (Figure 3B and 3D), the alkene is clearly the most oxidizable species (Figure 3A/A’). Moreover, it is clear that involvement of the conjugate base of the sulfonylacetamide is key; trapping of either the alkene radical cation with the sulfonylacetamide or its direct oxidation are prohibitively high in energy (Figure 3A’ and 3C).

Figure 3.

Calculated ionization potentials of aminoarylation starting materials and free energy changes at 298 K (in kcal/mol) for the various reaction paths to the putative benzylic radical intermediate. The calculations were carried out using B3LYP(D3)/CBSB7+ with bulk solvation by DMF estimated using a conductor-like polarized continuum model (CPCM).

Oxidation of the conjugate base of the sulfonylacetamide or an H-bonded complex of the sulfonylacetamide was also possible given the equilibria between the starting amide and benzoate (Figure 4A). Importantly, single electron oxidation of the H-bonded complex was not associated with proton transfer to benzoate contrary to what would be expected for a MS-CPET pathway 3D (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Acid-base equilibria of benzoate and sulfonylacetamide starting materials along with calculated molecular orbitals (MOs)of the H-bonded benzoate-sulfonylacetamide complex (4A). Calculated MOs do not support MS-CPET pathway (Figure 3D) as H+ transfer is not predicted upon single electron oxidation of the complex. Stern-Volmer (SV) luminescence quenching of relevant starting materials (4B). The SV data also supports alkene radical cation hypothesis (Figure 3A) rather than sulfonylacetamide SPLET or MS-CPET (Figure 3B and 3D). Calculated bond dissociation enthalpies of benzenesulfonylacetamide and benzoic acid (4C). Hydrogen atom transfer from the latter to the former is endergonic. The calculations were carried out using B3LYP(D3)/CBSB7+ with solvation by DMF estimated using a polarized continuum model.

Experimental corroboration from Stern-Volmer quenching studies (Figure 4B) was sought since the computations alone could not definitively address which of paths 3A, 3B, or 3D was operative. Consistent with our previous observations, alkene trans-anethole (E1/2 = +1.24 V versus SCE in MeCN)50 was able to quench the excited state of the Ir photocatalyst (*E1/2 IrIII*/IrII = +1.68 V versus SCE in MeCN),51 with KSV = 327 M−1. Importantly, neither the benzenesulfonylacetamide nor mixtures of the benzenesulfonylacetamide with base (tetrabutylammonium benzoate) efficiently quenched the photolcatalyst (KSV = 67 M−1 for the former alone). If pathway 3B or 3D were operative, the latter combination of base and sulfonylacetamide would be expected to quench the excited state of the photocatalyst forming a sulfonamidyl radical. The absence of quenching from the mixtures is strong evidence in favor of path 3A.

Interestingly, tetrabutylammonium benzoate (E1/2 = +1.40 V versus SCE in MeCN)50 alone was able to quench the excited state of the photocatalyst very efficiently with Ksv = 340 M−1. However, hydrogen atom transfer from the sulfonylacetamide N–H to the putative benzoyloxyl radical formed upon quenching by benzoate is unlikely: in addition to the calculated endergonicity of this process (Figure 4C), the concentration of free benzoate must be small given its substoichiometric loading under synthetic conditions and the equilibria in Figure 4A. Thus, alkene radical cation pathway 3A emerges as the most likely mechanism for the coupling of the sulfonylacetamide and alkene towards the formation of the intermediate benzylic radical.

B. Steric and Electronic Effects on Alkene Reactivity

Given the foregoing conclusions, it is expected that the reaction efficiency would depend on the oxidation potential of the olefin. Moreover, the steric profile of the olefin can also not be discounted; formation of a spirocyclic Meisenheimer-like intermediate during aryl transfer should also be impacted by olefin substitution. Therefore, a sterically varied series of electron-rich olefins were subjected to the optimized reaction conditions with p-trifluoromethylbenzenesulfonylacetamide 1a (Figure 5A). The monosubstituted alkene vinyl anisole (2aa) delivered 38% of the corresponding aminoarylation product 3aa. More sterically demanding olefins such as the trisubstituted 2ac also gave 38% of the desired aminoarylation product 3ac. X–ray crystallographic analysis of 3ac yielded only the syn-aminoarylation product as in our previous work.31 The desired aminoarylation product was not observed with trisbustituted alkene 2ag and tetrasubstituted alkene 2ah reflecting the delicate steric requirements of the 5-exo-trig cyclization (vide infra). These alkenes would also be expected to experience increased steric repulsion in the initial C-N coupling. Given these trends, trans-anethole 2a appears to have the optimal balance between radical cation stabilization and steric accessibility for the 5-exo-trig cyclization.

Figure 5.

Alkene scope features aryl alkenes (5A). Tetrabutylammonium salt experiments support sulfonylacetamide conjugate base addition to an alkene radical cation rather than sulfonacetamidyl radical addition to an alkene (5B). aYield determined by 19F NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture.

Other electron-rich alkenes gave modest yields of aminoarylation product, including L-dopa analog 3ae. Electronically neutral alkene substrates such as 1-methylcyclohexene did not deliver the desired aminoarylation product (see supplementary information section V). Presumably, the higher oxidation potential of these alkenes prevents formation of an alkene radical cation intermediate leading to a lack of desired reactivity. However, products 3aj and 3ak could be obtained from thiophene and furan derived alkenes, demonstrating the competency of aryl alkene substrates which did not feature a para-methoxyphenyl activating group. These products also suggest the importance of π-stacking interactions in the transition state structures of these transformations (vide infra section D).

Additional synthetic evidence for pathway 3A was obtained via subjection of the independently synthesized tetrabutylammonium sulfonylacetazanide 4a to the reaction conditions (Figure 5B). In the absence of base and with trans-anethole 2a as the alkene reaction partner, 52% of the desired aminoarylation product was isolated along with 32% of conjugate acid sulfonylacetamide 1a. Subjection of this same salt 4a with the electron-neutral β-methylstyrene 2i under the same conditions resulted in formation of trace aminoarylated product as detected by analysis of the crude reaction mixture by 19F NMR spectroscopy (Figure 5B). The sulfonylacetamide 1a was isolated in 75% yield. If a sulfonamidyl radical were generated by oxidation of 4a, given literature precedent, the corresponding aminoarylation product could be expected in higher yield.23 It is worth noting, however, that styrene was also a poor reaction partner with sulfonamidyl radicals in the cited work from Knowles.

These above results can be understood by comparison of the alkene and photocatalyst oxidation potentials. The oxidation potential of β-methylstyrene, (+1.74 V versus SCE in MeCN) is slightly beyond that of the excited state of the Ir photocatalyst [Ir]-1 (+1.68 V versus SCE in MeCN), making formation of the required alkene radical cation as in pathway 3A more endergonic leading to a decreased concentration of its radical cation. With a lower concentration of radical cation of 2i to trap, back-electron transfer from Ir can compete with desired C–N coupling thus diminishing aminoarylation reactivity. In all, these final two experiments and the other above computational and experimental studies substantiate the alkene radical cation pathway 3A, while rejecting the SPLET pathway 3B and MS-CPET pathway 3D.

C. Sulfonamide N-H Acidity and Reaction Efficiency

The effect of N–H bond acidity and base loading on the reaction was investigated as these variables modulate the nucleophilicity and concentration of deprotonated sulfonamide. This anion is necessary for alkene radical cation capture via pathway 3A. Therefore, a series of carbamate and acyl protected sulfonamides were synthesized and subjected to the optimized reaction conditions. The relative acidity of these substrates was qualitatively ranked according to the N–H proton shift in MeCN-d3 with further downfield N–H shifts corresponding to a more acidic N–H bond (Figure 6A). The desired amino arylation products were only observed for substrates with an N–H shift between 9.17 ppm and 9.61 ppm. This narrow shift range reflects the delicate balance necessary between N–H acidity and anion nucleophilicity for aminoarylation reactivity. The yield of the desired aminoarylation product correlated with increasing N–H acidity up to the optimal acyl protecting group. Sulfonylacetamides have reported pKa values similar to that of benzoic acid (4.2 in H2O).52 Indeed, we have calculated that the equilibrium between benzoate and 1m has ΔG = −0.3 kcal/mol, favoring the conjugate base of 1m (Keq = 1.66 at 25 °C) These well-matched acidities ensure sufficient concentrations of the conjugate base of sulfonylacetamide to capture the alkene radical cation compared to the less acidic carbamate protected sulfonamides 1ah-1ai which afford poor yields. Despite having the most acidic N-H bond, the lack of observed aminoarylation product from trifluoromethylacyl protected sulfonamide 1al may be attributed to its severely attenuated nucleophilicity from its strongly electron-withdrawing trifluoroacyl group. In benzenesulfonylacetamide starting material (conditions 6B-a). Thisresult reinforces the formation of the sulfonylacetamide conjugate base as beneficial to desired reactivity. Buffered conditions with 0.3 equivalents of both potassium benzoate and benzoic acid did not result in any loss in reaction efficiency (conditions 6B-b). Finally, superstoichiometric benzoate loading (1.5 equivalents of tetrabutylammonium benzoate) resulted in isolation of only 25% of the aminoarylation product with 57% unreacted sulfonylacetamide (conditions 6B-c). This decrease in reaction efficiency in the presence of superstroichiometric base may be attributed to competitive, non-productive electron transfer from benzoate over trans-anethole given their similar Stern-Volmer quenching constants (vide supra). Quenching of the Ir excited state by benzoate base would lead to a benzoyloxyl radical53, but our previous computations (Figure 4C) indicate that this species is unlikely to perform productive HAT with the sulfonylacetamide starting material due to the endergonicity of this step. Once again, alkene radical cation capture by the conjugate base of the arylsulfonylacetamide as in pathway 3E remains the most likely C–N coupling mechanism

Figure 6.

N–H Bond acidity effect on aminoarylation yield. 1H NMR shifts obtained in MeCN-d3. (6A). Effect of of acidic conditions (a), buffered conditions (b), and super-stoichiometric base loading (c) on the aminoarylation reaction of benzenesulfonylacetamide 1a and trans-anethole 2a. Sub-stoichiometric loading of base (standard) gives optimum reactivity (6B).

D. Smiles-Truce Rearrangement and Arene Electronics

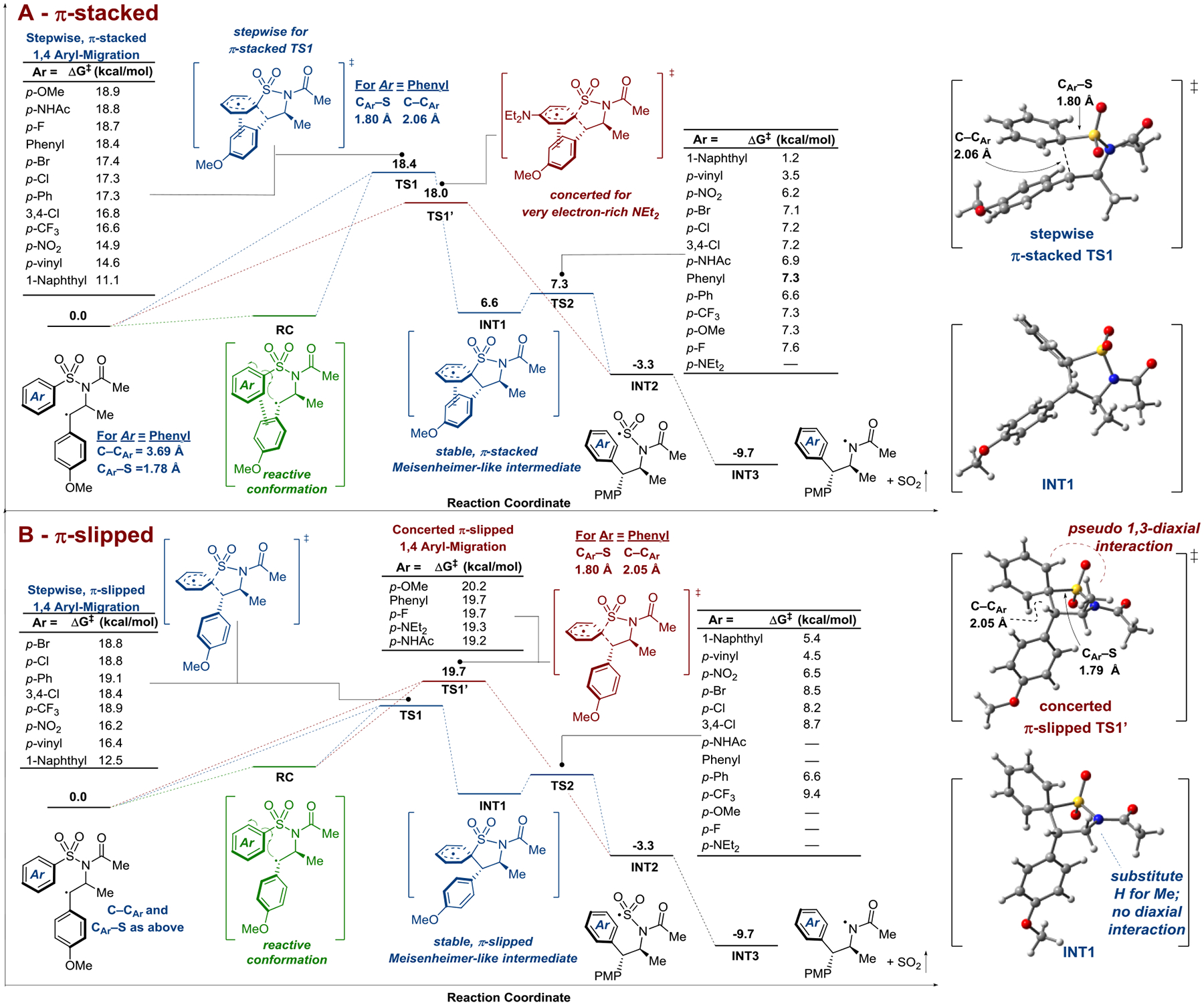

The 1,4-aryl shifts in the radical intermediates arising from a series of substituted benzenesulfonylacetamides as well as 1-naphthylsulfonylacetamide were investigated by computation (Figure 7). Initial calculations were carried at the CBS-QB3(+) level of theory incorporating Grimme’s D3 empirical dispersion correction for density functionals on a truncated analog of benzenesulfonylacetamide 1m with the phenyl group replaced with a methyl group.54,55 Contributions to the free energies of the relevant species from solvation by DMF were estimated using a conductor-like polarized continuum model.56 Given the good agreement between these results and those afforded by only the initial B3LYP(D3)/CBSB7+ steps of the CBS-QB3(+) treatment (see supplementary information section VII for further details), subsequent calculations were carried out using the truncated, less computationally intensive approach.

Figure 7.

Calculated reaction coordinates for the 1,4-aryl shift in the key benzylic radical intermediate derived from the reaction of benzenesulfonylacetamide 1m with trans-anethole and subsequent desulfonylation. Corresponding barriers for substituted benzenesulfonylacetamides are also shown. Figure 7A depicts the π-stacked reaction pathway in which the migrating aryl group interacts with the para-methoxyphenyl group from the trans-anethole model alkene. Figure 7B depicts the π-slipped reaction pathway in which the migrating aryl group does not have a significant interaction. Stepwise or concerted 1,4 aryl migrations are possible from either the stacked or slipped pathways, depending on the electronics of the migrating arene and the sterics of the alkene. The slipped pathway results in systematically higher energies, along with more substrates favoring concerted aryl transfer. This is due to the slipped species experiencing a destabilizing pseudo 1,3-diaxial interaction (depending on the substitution of the alkene starting material). (7B top right). The absence of this diaxial interaction results in a stable, slipped Meisenheimer-like intermediate (7B bottom right). INT2 and INT3 energies are the same for either pathway. The calculations were carried out using B3LYP(D3)/CBSB7+ with solvation by DMF estimated using a conductor-like polarized continuum model (CPCM).

For the rearrangement of the unsubstituted benzenesulfonylacetamide 1m with trans-anethole 2a, two transition state structures (7A-TS1 and 7B-TS1’, Ar = Phenyl) were readily identified using this approach which differed with respect to the positions of the aryl rings, leading us to describe them as π-stacked (Figure 7A) and π-slipped (Figure 7B) geometries.

The π-stacked 7A-TS1 structure has a free energy which is 18.4 kcal/mol higher above that of the minimum energy conformation of the benzylic radical. The structure shows C-C bond formation to be well advanced of C-S bond cleavage (i.e. the distance between the benzylic carbon and the ipso carbon of the migrating phenyl group was reduced from 3.69 Å to 2.06 Å while the C-S bond length only increased from 1.78 Å to 1.80 Å when comparing the benzylic radical and 7A-TS1). Intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations confirm that 7A-TS1 connects the reactive conformation of the starting benzylic radical 7A-RC to a discrete Meisenheimer-like intermediate 7A-INT1. From 7A-INT1, the subsequent rearomatization to 7A-INT2 via 7A-TS2 was determined to be nearly barrierless (ΔG‡ = + 0.7 kcal/mol).

The π-slipped 7B-TS1’ structure also shows C–C bond formation to be well-advanced of C-S bond cleavage (i.e. the distance between the benzylic carbon and the ipso carbon of the migrating phenyl group was reduced from 3.69 Å to 2.05 Å while the C–S bond length only increased from 1.78 Å to only 1.79 Å). Importantly, in this case, IRC calculations indicated that 7B-TS1’ directly connects the reactive conformation of the starting benzylic radical 7B-RC to the fully 1,4-aryl transferred intermediate 7B-INT2. This frontside attack and direct displacement of a leaving group from the arene has an analogy in another calculated concerted SNAr reaction.57 However, 7B-TS1’ lies 1.3 kcal/mol higher in energy than 7A-TS1 (overall ΔG = +19.7 kcal/mol). Concerted aryl transfer via Meisenheimer-like transition states with largely intact CAr–S bonds as is suggested in the π-slipped 7B-TS1’ has also been calculated by Legnani and Vidari for ionic Smiles rearrangements and in a recent report by Nevado for radical Smiles-Truce rearrangements.58,46 Models of 7A-TS1, 7B-TS1’, and 7A/7B-INT1 are illustrated to the far right of Figure 7, while the relative energies of relevant intermediates for other migrating aryl groups can be found in the supplementary information.

Two TS structures were also identified when the phenyl ring was exchanged for a naphthyl ring. Again, the π-stacked 7A-TS1 was lower in energy than the π-slipped 7B-TS1 (ΔG = +11.1 and +12.5 kcal/mol, respectively). Both processes have significantly lower barriers for 1,4-aryl migration than the analogous processes in the phenyl-containing substrate 1m, consistent with the efficiency with which 1m and the naphthyl analog undergo the aminoarylation chemistry at room temperature. By extension, it seems that increased conjugation and decreased aromatic character is likely to contribute significantly to the successful use of heteroaryl-substituted substrates in these transformations as well.32,59 Consistent with the potential for the naphthyl substrate to yield more highly-delocalized Meisenheimer-like intermediates, both 7A-TS1 and 7B-TS1 were connected to intermediates 7A/7B-INT1 (see SI for relative energies). Rearomatization for the naphthyl substrate from 7A/7B-INT1 to 7A/7B-INT2 gave the largest activation energies of the interrogated substrates (ΔG‡ = +2.5 and +2.0 kcal/mol via 7A-TS2 and 7B-TS2, respectively).

Corresponding calculations of the 1,4-aryl shifts of the benzylic radicals derived from para-substituted benzenesulfonyl substrates revealed several interesting trends. In general, the substituted systems had similar TS and TS’ structures to those already described, with well-advanced C–C bond formation. Furthermore, the π-slipped 7B-TS1/TS1’ structures of these substrates were also systematically higher in energy than their π-stacked 7A-TS1/TS1’ structures. Migrating aryl group electronics contributed to determining the barrier to aryl transfer regardless of whether the process was stepwise or concerted. Aryl substitution with electron-withdrawing groups was associated with lower calculated barriers relative to the unsubstituted 1m (ΔG‡≈15–17 and ~16–19 kcal/mol via the 7A-TS1 and 7B-TS1/TS1’ structures, respectively). Favorable through-space interactions between the electron-deficient aryl rings of these substrates with the electron-rich PMP ring likely contributes to their systematically lower energies, particularly in the π-stacked pathway. These electron-deficient substrates favored stepwise aryl transfer (via 7A-TS1 or 7B-TS1 structures) regardless of via the π-stacked or π-slipped geometries.

Substitution with electron-donating groups gave higher calculated barriers to aryl transfer, which were mostly invariant between the π-stacked and π-slipped pathways (ΔG‡≈18–20 for both the 7A-TS1 and 7B-TS1’ structures), and presumably a consequence of repulsion between the electron-rich rings. Interestingly, IRC calculations revealed that both 7A-TS1’ and 7B-TS1’ of the p-NEt2 substituted analogue connected the reactive conformation of the starting benzylic radical directly to the rearranged sulfonyl radical 7A/7B-INT2. Likewise, the 1,4-aryl shift proceeding via 7B-TS1’ for the p-F, p-OMe and p-NHAc analogues were predicted to proceed via a concerted mechanism. However, these substrates were still predicted to slightly favor stepwise 1,4-aryl shifts from their π-stacked 7A-TS1 structures.

Substitution with electron-neutral groups gave similar activation energies to the unsubstituted substrate 1m, unless these groups introduced the possibility for extended conjugation (i.e. Ar = p-Ph or p-vinyl). In these latter cases, aryl transfer barriers were lower than 1m, in line with the benefit of increased radical delocalization through conjugation as previously discussed for the 1-naphthyl substrate. These substrates were also predicted to favor stepwise aryl transfer irrespective of the 7A/7B-TS1 structure.

However, if the TS/TS’ energies were dictated solely by electronic effects such as the electron-donating ability of these various functional groups, the highly donating p-NEt2 group should have 7A/7B-TS1’ barriers at the extremum of the substrate series. Importantly, its calculated TS1’ values belie this assumption; they are of intermediate values relative to less electron-rich substrates such as p-OMe. Consequently, the delicate interaction of several competing electronic and steric effects must dictate the overall energy of the Meisenheimer-like transition states TS1/TS1’.

The systematically higher energies of the π-slipped 7B-TS1/TS1’ relative to the π-stacked 7A-TS1 for a given substrate appears to be based primarily on steric effects (Figure 7B right). The origin of this destabilization in the π-slipped 7B-TS1/TS1’ was determined to be pseudo-1,3 di-axial interactions between the spirocycle moiety and the methyl group derived from trans-anethole 2a. These diaxial interactions, however, are absent in the π-stacked 7A-TS1/TS1’ structures where the relevant groups are pseudo-1,3 di-equatorial.

This steric destabilization also appears to contribute to the preference for concerted aryl shifts via 7B-TS1’ for substrates that would otherwise undergo a stepwise 1,4-aryl shift via 7A-TS1 (e.g. 1m). This is supported by calculations in which the β-methyl group from trans-anethole was replaced with a hydrogen atom. In this case, a stable Meisenheimer-like intermediate INT1 was located on the reaction coordinate (Figure 7B bottom right). Thus, the mechanism of 1,4-aryl transfer in this system is sensitive not only to the electronics of the migrating aryl group, but also the steric profile of the alkene reaction partner. This is consistent with the observation that more highly-substituted PMP containing alkenes did not perform as well as trans-anethole 2a in the reaction (vide supra).

In all, while the π-stacked 7A-TS1 was favored and is majorly operative for all substrates studied herein, the contribution of the concerted π-slipped 7B-TS1’ has been shown to not be insignificant for certain electron-rich arylsulfonylacetamide substrates (e.g. from the ΔΔG‡ = 0.4 kcal/mol between 7A-TS1 and 7B-TS1’ for p-NHAc substrate 1u, 1 in 3 reactions would be predicted to occur by 7B-TS1’). In addition to electron-rich migrating arenes, increased steric bulk of the alkene promotes concerted reactivity.

A lingering question from the initial report was the manner in which SO2 extrusion and photocatalyst turnover occurred. The former point is relevant as it has been shown that feasibility of SO2 extrusion is oftentimes dependent on the resultant radical species.60 We considered that rearomatization during aryl transfer could result in direct extrusion of SO2 to an amidyl radical, or, simpler C–S bond cleavage to an S-centered sulfonyl radical (Figure 2). Either of these radical species was hypothesized to oxidize the reduced Ir(II) photocatalyst back to its ground state in order to complete the photocatalytic cycle. Whether by a concerted or stepwise mechanism, sulfonyl radical 7A/7B-INT2 resulted following aryl transfer. That is, rearomatization of the radical Meisenheimer-like transition state 7B-TS1’ or intermediate 7A/7B-INT1 does not result in direct extrusion of SO2 to an amidyl radical. However, S–N bond cleavage resulting in liberation of SO2 from 7A/7B-INT2 does ultimately give an amidyl radical intermediate 7-INT3. This exergonic step is driven by an increase in entropy with release of the SO2 gas, as cleavage of the S–N bond is a highly endothermic process (see supplementary information section VII for ΔΗ values). It is hypothesized that single-electron reduction of 7-INT3 results in catalyst turnover while irreversible protonation of the resultant stabilized N-anion gives the observed amide products.

E. Diastereoselectivity and Reaction Profile

We envisioned that the high observed diastereoselectivity in this transformation was imparted in the course of aryl transfer due to the conformation of the benzylic radical intermediate during 5-exo-trig cyclization. In the previous report, both trans and cis-anethole furnished exclusively the syn-aminoarylation products. From these results, we hypothesized that there was a preferential adoption of an anti-periplanar relationship between the methyl and aryl portion of the former PMP-alkene in order to avoid otherwise unfavorable steric interactions in the benzylic radical intermediate. This conformation would cyclize to form the observed syn-aminoarylated product. The foregoing computations provided additional insight to this point; the syn- and anti-diastereomeric transition states of benzenesuflonylacetamide 1m yielded a difference of 5.6 kcal/mol in favor of the transition state leading to the syn-product. This difference in ΔG‡ is consistent with the observed >20:1 d.r. favoring the syn-aminoarylation product (Figure 8A). Furthermore, the irreversibility of the aryl transfer due to the extrusion of SO2 followed by reduction and protonation of the resultant amidyl radical ensures exclusive syn-aminoarylation.

Figure 8.

Diastereoselectivity rationale based on computed conformational analysis of benzylic radical intermediate. Calculations were performed at B3LYP/CBSB7 level of theory in DMF with dispersion corrections (A). 1H LED-NMR reaction monitoring with benzenesulfonylacetamide 1a conducted according to optimized reaction conditions in DMF-d7. In situ alkene isomerization still maintains the observed >20:1 d.r. (B).

Additional experimental support was provided by in situ LED-NMR monitoring of the reaction with benzenesulfonylacetamide 1a and trans-anethole 2a. During the course of the reaction, the only observed species by 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopy corresponded to the starting materials and syn-aminoarylation product. Isomerization of trans-anethole to cis-anethole was also observed, as described in our previous report, but did not result in anti-aminoarylation product (Figure 8B).

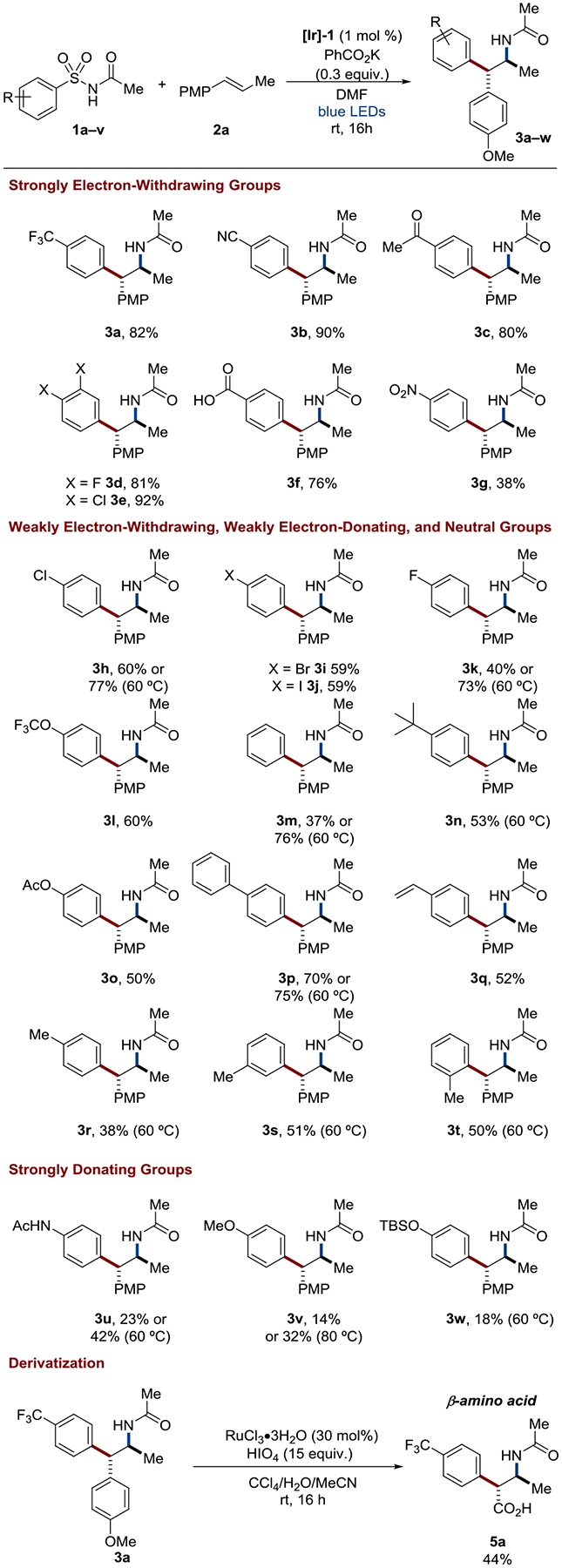

F. Expanded Arene Scope

In order to provide experimental corroboration of the trends in the computational results presented in Figure 7, a series of 23 electronically diverse benezenesulfonylacetamides were synthesized and subjected to the optimized reaction conditions (Figure 9). A wide variety of arene electronics were tolerated with highly electron-deficient systems (3a-3g) providing the aminoarylation product in good to excellent yield at room temperature, consistent with the lower barriers predicted for 1,4-aryl shifts in electron-poor substrates. Interestingly, benzoic acid 1f did not require additional base and gave product 3f in 76% yield. Derivatization of 3a to a non-canonical β-amino acid analog 5a was achieved in a two-step sequence in 54% yield.

Figure 9.

Diverse aryl scope of alkene aminoarylation. Simply heating reactions with challenging electron-neutral or electron-rich substrates helped to recover desired reactivity in line with their higher calculated TS1/TS1’ energies (Figure 7). Reactions run at RT unless otherwise noted. All yields are isolated yields. The d.r. is > 20:1 unless otherwise noted.

Weak electron withdrawing/donating and neutral substituted benzensulfonylacetamides provided the corresponding products in good yields (3h-3t), albeit reduced relative to the strongly deficient substrates. In light of their greater calculated aryl transfer barriers, it was envisioned that simply heating the reaction for these substrates would overcome the greater barriers. Gratifyingly, increasing the temperature to 60 °C for unsubstituted benezenesulfonylacetamide 1m resulted in isolation of the desired aminoarylation product 3m in 76% yield. This is on par with the previously reported hetero– or multicyclic aromatic or electron-deficient benzenesulfonylacetamide substrates.32 Indeed, simply increasing reaction temperatures proved a general solution to successful aryl transfer from electron-neutral and electron-rich substrates. Extended π-conjugation in 1p and 1q was beneficial for the desired transformations giving good yields of 3p and 3q at room temperature. Ortho substitution in o-tolylsulfonylacetamide 1t did not diminish reactivity relative to meta (1s) and para (1r) isomers with comparable yields of 3r–3t obtained.

Lastly, electron-rich systems provided moderate yields of the corresponding aminoarylation products. Again, increased yields could be had by raising the reaction temperature, as indicated by 3u and 3v. The feasibility of nucleophilic aromatic substitutions on electron-rich aryl systems has recently been invoked as hallmark of concerted aryl transfer mechanisms.61,62 This is consistent with the small calculated ΔΔG‡ (within ~2 kcal/mol) between the stepwise and concerted mechanisms for these electron-rich substrates (Figure 7 It is likely that the exceptional leaving group ability of the sulfonyl group plays a large part in enabling aryl transfer for these more challenging electron-rich substrates, as is observed in other Smiles-Truce rearrangement methodologies utilizing SO2.63). Unfortunately, a p-NEt2 substituted benzenesulfonylacetamide (as tested in our calculations) did not undergo the rearrangement due to oxidative N-dealkylation of the p-NEt2 group (see supplementary information section V).

G. Linear Free Energy Correlation and Radical Probe Experiments

With the foregoing substrates in hand, we sought to carry out kinetic experiments in order to corroborate the structure-reactivity relationships predicted by computation and provide additional information that may aid in discriminating between the concerted and step-wise mechanisms. Initial rate kinetics were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy (to ~10% product formation) for the reactions of 1v, 1u, 1m, 1i, and 1a, and gave a good correlation with the σ− parameter with ρ = +1.58 (Figure 10).64

Figure 10.

Correlation of the rate of aminoarylation with σ− is consistent with increasing electron density on the benzenesulfonyl moiety in the rate-determining step of the reaction.

The correlation versus σ− suggests that there is development of excess electron density in the aryl system consistent with the addition of the nucleophilic (p-OMe) benzylic radical to the aryl ring. This value is also in agreement with a greater degree of C–CAr bond formation than CAr–S cleavage during aryl transfer as indicated by the above calculated C–CAr and CAr–S bond distances directly before and at the transition state(s) of the rearrangement (Figure 7). Such bond length effects were computed by Jacobsen and Williams in their studies of concerted nucleophilic aromatic substitutions.44,65 Importantly, the ρ = 1.58 is consistent with previously reported ρ-values for concerted nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions by Ritter, Williams, Fry, Miyazaki, and others.65–73 In contrast to this ρ-value, a fully anionic Meseinheimer intermediate from a stepwise nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction typically displays ρ-values between 3 and 8.66,67,74 The lower ρ-value in this study thus satisfactorily reflects the radical rather than anionic nature of this rearrangement. This fact is important given the significant contribution of ring through-space interactions to the 7-TS1/TS1’ energies detailed previously; an anionic Meisenheimer intermediate would experience unfavorable repulsion with the electron-rich PMP group utilized in these reactions. Delightfully, a calculated Hammett plot resulted in a ρ = 1.59 in excellent agreement with the experimental plot discussed above (see supplementary information section VI).

The role of a radical intermediate in the reaction would be most convincingly established using a substrate wherein the radical intermediate could be diverted to another reaction path, e.g. a known radical rearrangement. To this end, we prepared arylsulfonylacetamide rac-5a, which was expected to react with trans-anethole under our optimized conditions via a radical intermediate that may be expected to undergo ring-opening (and subsequent closure to epimerize the cyclopropane (Figure 11). Newcomb has measured the rate constant of ring-opening of the 2-phenylcyclopropylcarbinyl radical to be 4×1011 s−1 at 25 °C, making it one of the fastest “radical clocks” designed to date.75 Of course, since the cyclohexadienyl radical intermediate in the 1,4-aryl migration is significantly more stable than the primary cyclopropylcarbinyl in Newcomb’s experiment, we expected this to be slower for the current system and calculated it to be 1.3×108 s−1 (see supplementary information section VI). Nevertheless, it presented the most reasonable opportunity to inform on the presence of a radical intermediate.

Figure 11.

No observed stereochemical scrambling is observed when the rac-5a kinetic probe is subjected to the optimized reaction conditions, suggesting that aryl migration is faster than ring opening of the cyclopropyl cyclohexadienyl radical (estimated to be 1.3 ×108 s−1).

If ring-opening of the cyclopropane were faster than the competing 1,4-aryl shift, stereochemical scrambling of the phenyl groups on the cyclopropane ring to the trans isomer would be observed in the aminoarylation product. On the other hand, stereochemical retention of the cis relationship between the cyclopropyl phenyl groups in the aminoarylation product would result if the 1,4-aryl shift was faster than the cyclopropylcarbinyl radical ring opening – or if the reaction were concerted.

Subjection of rac-5a to the optimized reaction conditions led to isolation of aminoarylation product mixture 6a in 27% yield as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers with exclusive cis stereochemistry at the cyclopropyl moieties in each diastereomer (Figure 11). The exclusive, retained cis relative stereochemistry was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Furthermore, 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture indicated the presence of only unreacted arylsulfonylacetamide, trans-anethole 2a and isomerized cis-anethole, and the set of signals corresponding to the isolated cis-cyclopropyl aminoarylation product diastereomer mixture (see supplementary information section VI). In addition to the lack of evidence for the trans-cyclopropyl aminoarylation product from the crude reaction mixture and obtained crystal structures, attempted HPLC separation on the isolated material did not indicate the formation of the trans-cyclopropyl diastereomer (see supplementary information). Thus, if the 1,4 aryl migration is step-wise, it must occur via a short-lived radical intermediate since rearomatization must occur with k ≥ 1.3×108 s−1. Indeed, the computations suggest a very small barrier for rearomatization (cf. Figure 7).

H. Summarized Mechanism and Conclusions

Taken together, the foregoing computational and experimental data furnish a refined mechanistic picture of our aminoarylation approach (Figure 12). Upon visible-light excitation of the IrIII photocatalyst, single-electron oxidation of an electron-rich alkene III provides its radical cation IV. This species is intercepted by the conjugate base of sulfonylacetamide II, which predominates in the acid-base equilibrium between I and the benzoate base. The subsequent carbon-centered radical intermediate V is well-poised to undergo the critical diastereoselective, rate-determining aryl transfer step. The 1,4-aryl transfer occurs via either a π-stacked or higher energy π-slipped transition state depending on the migrating arene electronics and alkene substitution at R2. The former pathway is predicted to be a stepwise process via a discrete, but short-lived radical Meisenheimer-like intermediate whereas the latter is predicted to be concerted for a variety of electron-neutral and electron-rich substrates. Electron deficient and multicyclic arenes favor stepwise pathways, whereas electron-neutral and electron-rich arenes could likely undergo either pathway. Furthermore, aryl migration was demonstrated to be more energetically favorable for electron-deficient arenes or multicyclic/heterocyclic arenes. A lower-bounds for the rate constant for 1,4-aryl transfer of 1.3×108 s’1 was estimated by a radical probe experiment with rac-5a. Sulfonyl radical intermediate VII resulted from either stepwise or concerted pathways. Extrusion of SO2 from VII forms an amidyl radical VIII, which upon single-electron reduction returns the ground state IrIII photocatalyst. Protonation of the resultant amide anion with benzoic acid generated from initial sulfonylacetamide deprotonation furnishes the aminoarylation product IX and returns benzoate for use by additional sulfonylacetamides. Alternatively, protonation of the amide anion by another equivalent of arylsulfonylacetamide substrate I can yield the next equivalent of conjugate base II.

Figure 12.

Refined mechanism of alkene aminoarylation informed by the studies detailed herein.

Synthetically, a large expansion in the scope of the alkene aminoarylation with respect to the migrating aryl group to accommodate benzenesulfonylacetamides was achieved (Figure 10). Our increased comprehension of this reaction has found application in diverse projects within our research groups including arene dearomatization methodology development76, droplet microfluidic reaction platform design77, and expansion of alkene aminoarylation to unactivated olefins.78 We hope this work will further facilitate the synthesis of valuable nitrogen containing scaffolds such as arylethylamines, inform future alkene difunctionalization and radical aryl transfer methods, and lead to the greater utilization of the Smiles-Truce rearrangement in synthesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support for this work was provided by the NIH NIGMS (R01GM127774 and R35GM144286) and the University of Michigan for grants to C.R.J.S. and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Canada Foundation for Innovation for grants to D.A.P. This work is supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship for R.C.M. (grant DGE 1256260) and A.R.A. (grant DGE 1256260).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and characterization data for all compounds. Crystal structures for relevant compounds. Bond coordinates, energies, and other computations for relevant structures. Stern-Volmer, Hammett, and reaction profile raw data and plots (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Nichols DE Amphetamine and Its Analogues; Psychopharmacology, Toxicology, and Abuse. In Amphetamine and Its Analogues; Psychopharmacology, Toxicology, and Abuse; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 1994; pp 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gallardo-Godoy A; Fierro A; McLean TH; Castillo M; Cassels BK; Reyes-Parada M; Nichols DE Sulfur-Substituted α-Alkyl Phenethylamines as Selective and Reversible MAO-A Inhibitors: Biological Activities, CoMFA Analysis, and Active Site Modeling. J. Med. Chem 2005, 48 (7), 2407–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Reti L β-Phenethylamines. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Physiology; Manske RHF, Holmes HL, Eds.; Academic Press, 1953; Vol. 3, pp 313–338. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Velander JR Suboxone: Rationale, Science, Misconceptions. Ochsner J 2018, 18 (1), 23–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Claes L; Janssen M; De Vos DE Organocatalytic Decarboxylation of Amino Acids as a Route to Bio-based Amines and Amides. ChemCatChem 2019, 11 (17), 4297–4306. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Senthamarai T; Murugesan K; Schneidewind J; Kalevaru NV; Baumann W; Neumann H; Kamer PCJ; Beller M; Jagadeesh RV Simple Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reductive Amination Enables the Synthesis of a Broad Range of Primary Amines. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Chakraborty S; Leitus G; Milstein D Selective Hydrogenation of Nitriles to Primary Amines Catalyzed by a Novel Iron Complex. Chem. Commun 2016, 52 (9), 1812–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Slotta KH; Szyszka G Über β-Phenyl-Äthylamine, IV. Mitteil.: Darstellung von β-[Amino-Phenyl]-Äthylaminen. Berichte der Dtsch. Chem. Gesellschaft (A B Ser 1935, 68 (1), 184–192. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kindler K; Peschke W; Brandt E Über Neue Und Über Verbesserte Wege Zum Aufbau von Pharmako-Logisch Wichtigen Aminen, XI. Mitteil.: Über Die Bereitung von Aryl-Äthylaminen Und von Aryl-Äthyanolaminen Durch Katalytische Reduktion. Berichte der Dtsch. Chem. Gesellschaft (A B Ser 1935, 68 (12), 2241–2245. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Benington F; Morin RD An Improved Synthesis of Mescaline. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1951, 73 (3), 1353–1353. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lundström J β-Phenethylamines and Ephedrines of Plant Origin. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology; Academic Press, 1989; Vol. 35, pp 77–154. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Wolfrum LA; Nordmeyer AS; Racine CW; Nichols SD Loperamide-Associated Opioid Use Disorder and Proposal of an Alternative Treatment with Buprenorphine. J. Addict. Med 2019, 13 (3), 245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nickell JR; Siripurapu KB; Vartak A; Crooks PA; Dwoskin LP The vesicular monoamine transporter-2: an important pharmacological target for the discovery of novel therapeutics to treat methamphetamine abuse. Adv Pharmacol 2014, 69, 71–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jiang H; Studer A Intermolecular Radical Carboamination of Alkenes. Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49, 1790–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yang Q; Ney JE; Wolfe JP Palladium-Catalyzed Tandem N-Arylation/Carboamination Reactions for the Stereoselective Synthesis of N-Aryl-2-Benzyl Pyrrolidines. Org. Lett 2005, 7 (13), 2575–2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Liu Z; Wang Y; Wang Z; Zeng T; Liu P; M. Engle K Catalytic Intermolecular Carboamination of Unactivated Alkenes via Directed Aminopalladation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (32), 11261–11270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Piou T; Rovis T Rhodium-Catalysed Syn-Carboamination of Alkenes via a Transient Directing Group. Nature 2015, 527 (7576), 86–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Legnani L; Morandi B Direct Catalytic Synthesis of Unprotected 2-Amino-1-Phenylethanols from Alkenes by Using Iron(II) Phthalocyanine. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2016, 55 (6), 2248–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Zhou K; Zhu Y; Fan W; Chen Y; Xu X; Zhang J; Zhao Y Late-Stage Functionalization of Aromatic Acids with Aliphatic Aziridines: Direct Approach to Form β-Branched Arylethylamine Backbones. ACS Catal 2019, 9 (8), 6738–6743. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Nguyen TM; Nicewicz DA Anti-Markovnikov Hydroamination of Alkenes Catalyzed by an Organic Photoredox System. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135 (26), 9588–9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Choi GJ; Knowles RR Catalytic Alkene Carboaminations Enabled by Oxidative Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (29), 9226–9229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Miller CD; Choi JG; Orbe SH; Knowles RR Catalytic Olefin Hydroamidation Enabled by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (42), 13492–13495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Nguyen QL; Knowles RR Catalytic C–N Bond-Forming Reactions Enabled by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Activation of Amide N–H Bonds. ACS Catal 2016, 6 (5), 2894–2903. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Zhu Q; Graff ED; Knowles RR Intermolecular Anti-Markovnikov Hydroamination of Unactivated Alkenes with Sulfonamides Enabled by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (2), 741–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Miller DC; Ganley MJ; Musacchio JA; Sherwood CT; Ewing RW; Knowles RR Anti-Markovnikov Hydroamination of Unactivated Alkenes with Primary Alkyl Amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (42), 16590–16594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Seath CP; Vogt DB; Xu Z; Boyington AJ; Jui NT Radical Hydroarylation of Functionalized Olefins and Mechanistic Investigation of Photocatalytic Pyridyl Radical Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (45), 15525–15534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Boyington AJ; Seath CP; Zearfoss AM; Xu Z; Jui NT Catalytic Strategy for Regioselective Arylethylamine Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (9), 4147–4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Pantaine LRE; Milligan JA; Matsui JK; Kelly CB; Molander GA Photoredox Radical/Polar Crossover Enables Construction of Saturated Nitrogen Heterocycles. Org. Lett 2019, 21 (7), 2317–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zheng S; Gutiérrez-Bonet Á; Molander GA Merging Photoredox PCET with Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling: Cascade Amidoarylation of Unactivated Olefins. Chem 2019, 5 (2), 339–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Faderl C; Budde S; Kachkovskyi G; Rackl D; Reiser O Visible Light-Mediated Decarboxylation Rearrangement Cascade of ω-Aryl-N-(Acyloxy)Phthalimides. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83 (19), 12192–12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Whalley DM; Duong HA; Greaney MF A Visible Light-Mediated, Decarboxylative, Desulfonylative Smiles Rearrangement for General Arylethylamine Syntheses. Chem. Commun 2020, 56 (77), 11493–11496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Whalley DM; Seayad J; Greaney MF Truce–Smiles Rearrangements by Strain Release: Harnessing Primary Alkyl Radicals for Metal-Free Arylation. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2021, 60 (41), 22219–22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).McAtee RC; McClain EJ; Stephenson CRJ Illuminating Photoredox Catalysis. Trends Chem 2019, 1 (1), 111–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Monos TM; McAtee RC; Stephenson CRJ Arylsulfonylacetamides as Bifunctional Reagents for Alkene Aminoarylation. Science (80-. ). 2018, 361 (6409), 1369 LP – 1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Alpers D; Cole KP; Stephenson CRJ Visible Light Mediated Aryl Migration by Homolytic C−N Cleavage of Aryl Amines. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2018, 57 (37), 12167–12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Douglas JJ; Albright H; Sevrin MJ; Cole KP; Stephenson CRJ A Visible-Light-Mediated Radical Smiles Rearrangement and Its Application to the Synthesis of a Difluoro-Substituted Spirocyclic ORL-1 Antagonist. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2015, 54 (49), 14898–14902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Truce EW; Ray JW; Norman LO; Eickemeyer BD Rearrangements of Aryl Sulfones. I. The Metalation and Rearrangement of Mesityl Phenyl Sulfone1. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1958, 80 (14), 3625–3629. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Naito T; Nagase O; Dohmori R; Sano M Rearrangement of Nitrobenzenesulfonamide Derivatives. I. Yakugaku Asshi 1954, 74 (6), 593–595. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Drozd VN Carbanion Rearrangement of O-Methyldiaryl Sulfones (The Truce Rearrangement). Int. J. Sulfur Chem 1973, 8 (3), 443–467. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Henderson ARP; Kosowan JR; Wood TE The Truce–Smiles Rearrangement and Related Reactions: A Review. Can. J. Chem 2017, 95 (5), 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Snape TJ A Truce on the Smiles Rearrangement: Revisiting an Old Reaction—the Truce–Smiles Rearrangement. Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37 (11), 2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Loven R; Speckamp WN A Novel 1,4 Arylradical Rearrangement. Tetrahedron Lett 1972, 13 (16), 1567–1570. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Tada M; Shijima H; Nakamura M Smiles-Type Free Radical Rearrangement of Aromatic Sulfonates and Sulfonamides: Syntheses of Arylethanols and Arylethylamines. Org. Biomol. Chem 2003, 1 (14), 2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kwan EE; Zeng Y; Besser HA; Jacobsen EN Concerted Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitutions. Nat. Chem 2018, 10 (9), 917–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Rohrbach S; Smith AJ; Pang JH; Poole DL; Tuttle T; Chiba S; Murphy JA Concerted Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2019, 58 (46), 16368–16388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Hervieu C; Kirillova MS; Suárez T; Müller M; Merino E; Nevado C Asymmetric, Visible Light-Mediated Radical Sulfinyl-Smiles Rearrangement to Access All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocentres. Nat. Chem 2021, 13, 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Griesser M; Chauvin J-PR; Pratt DA The Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reactivity of Sulfinic Acids. Chem. Sci 2018, 9 (36), 7218–7229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Allen RA; Noten AE; Stephenson RJC Aryl Transfer Strategies Mediated by Photoinduced Electron Transfer. Chem. Rev 2021, 122 (2), 2695–2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Monos TM; McAtee RC; Stephenson CRJ Arylsulfonylacetamides as Bifunctional Reagents for Alkene Aminoarylation. Science (80-. ). 2018, 361 (6409), 1369–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Roth H; Romero N; Nicewicz D Experimental and Calculated Electrochemical Potentials of Common Organic Molecules for Applications to Single-Electron Redox Chemistry. Synlett 2015, 27 (05), 714–723. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Choi GJ; Zhu Q; Miller DC; Gu CJ; Knowles RR Catalytic Alkylation of Remote C–H Bonds Enabled by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Nature 2016, 539 (7628), 268–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Lassalas P; Gay B; Lasfargeas C; James MJ; Tran V; Vijayendran KG; Brunden KR; Kozlowski MC; Thomas CJ; Smith AB Structure Property Relationships of Carboxylic Acid Isosteres. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 3183–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mukherjee S; Maji B; Tlahuext-Aca A; Glorius F Visible-Light-Promoted Activation of Unactivated C(Sp3)–H Bonds and Their Selective Trifluoromethylthiolation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138 (50), 16200–16203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Montgomery JA; Frisch MJ; Ochterski JW; Petersson GA A Complete Basis Set Model Chemistry. VI. Use of Density Functional Geometries and Frequencies. J. Chem. Phys 1999, 110 (6), 2822–2827. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Grimme S; Antony J; Ehrlich S; Krieg H A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys 2010, 132 (15), 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Barone V; Cossi M Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102 (11), 1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Park NH; Dos Passos Gomes G; Fevre M; Jones GO; Alabugin IV; Hedrick JL Organocatalyzed Synthesis of Fluorinated Poly(Aryl Thioethers). Nat. Commun 2017, 8 (1), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Legnani L; Porta A; Caramella P; Toma L; Zanoni G; Vidari G Computational Mechanistic Study of the Julia–Kocieński Reaction. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80 (6), 3092–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).L. Franklin J Calculation of Resonance Energies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1950, 72 (9), 4278–4280. [Google Scholar]

- (60).dos Passos Gomes G; Wimmer A; Smith MJ; König B; Alabugin VI CO2 or SO2: Should It Stay, or Should It Go? J. Org. Chem 2019, 84 (10), 6232–6243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Schimler SD; Cismesia MA; Hanley PS; Froese RDJ; Jansma MJ; Bland DC; Sanford MS; D. Nucleophilic Deoxyfluorination of Phenols via Aryl Fluorosulfonate Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (4), 1452–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Leonard DJ; Ward JW; Clayden J Asymmetric α-Arylation of Amino Acids. Nature 2018, 562 (7725), 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Bertrand MP; Bellrand LCMO UKA MP Recent Progress in the Use of Sulfonyl Radicals in Organic Synthesis. A Review. Org. Prep. Proced. Int 1994, 26 (3), 257–290. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Hansch C; Leo A; Taft RW, A Survey of Hammett Substituent Constants and Resonance and Field Parameters. Chem. Rev 1991, 91 (2), 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Shakes J; Raymond C; Rettura D; Williams A Concerted Displacement Mechanisms at Trigonal Carbon: The Aminolysis of 4-Aryloxy-2,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-Triazines. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1996, No. 8, 1553. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Neumann CN; Hooker JM; Ritter T Concerted Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution with 19F− and 18F−. Nature 2016, 534 (7607), 369–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Fry ES; Pienta JN Effects of Molten Salts on Reactions. Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution by Halide Ions in Molten Dodecyltributylphosphonium Salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107 (22), 6399–6400. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Cullum NR; Rettura D; Whitmore JMJ; Williams A The Aminolysis and Hydrolysis of N-(4,6-Diphenoxy-1,3,5-Triazin-2-Yl) Substituted Pyridinium Salts: Concerted Displacement Mechanism. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1996, No. 8, 1559. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Jacobsen H; Donahue JP Expanding the Scope of the Newman–Kwart Rearrangement — A Computational Assessment. Can. J. Chem 2006, 84 (11), 1567–1574. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Lloyd-Jones* G; Moseley J; Renny J Mechanism and Application of the Newman-Kwart O→S Rearrangement of O -Aryl Thiocarbamates. Synthesis (Stuttg). 2008, 2008 (5), 661–689. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Burns M; Lloyd-Jones GC; Moseley JD; Renny JS The Molecularity of the Newman−Kwart Rearrangement. J. Org. Chem 2010, 75 (19), 6347–6353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Cruz CL; Nicewicz DA Mechanistic Investigations into the Cation Radical Newman–Kwart Rearrangement. ACS Catal 2019, 9 (5), 3926–3935. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Miyazaki K The Thermal Rearrangement of Thionocarbamates to Thiolcarbamates. Tetrahedron Lett 1968, 9 (23), 2793–2798. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Miller J; Kai-Yan W 655. The S N Mechanism in Aromatic Compounds. Part XXIX. Some Para-Substituted Chlorobenzenes. J. Chem. Soc 1963, No. 0, 3492. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Newcomb M; Johnson CC; Beata Manek M; Varick RT Picosecond Radical Kinetics. Ring Openings of Phenyl-Substituted Cyclopropylcarbinyl Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114 (27), 10915–10921. [Google Scholar]

- (76).McAtee RC; Noten EA; Stephenson CRJ Arene Dearomatization through a Catalytic N-Centered Radical Cascade Reaction. Nat. Commun 2020, 11 (1), 2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Sun AC; Steyer DJ; Allen AR; Payne EM; Kennedy RT; Stephenson CRJ A Droplet Microfluidic Platform for High-Throughput Photochemical Reaction Discovery. Nat. Commun 2020, 11 (1), 6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Noten EA; McAtee RC; Stephenson CRJ Catalytic Intramolecular Aminoarylation of Unactivated Alkenes with Aryl Sulfonamides Chem. Sci, 2022, Advance Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.