Abstract

Meloxicam is an analgesic and anti-inflammatory drug widely prescribed in current therapeutics that exhibits very low solubility in water. Thus, this physicochemical property has been studied in N-methyl-pyrrolidone (NMP)–aqueous mixtures at several temperatures to expand the solubility database about pharmaceutical compounds in aqueous–mixed solvents. The flask-shake method and UV–vis spectrophotometry were used for meloxicam solubility determination as a function of temperature and mixture composition. Several cosolvency models, including the Jouyban–Acree model, were challenged for equilibrium solubility correlation and/or prediction. The van’t Hoff and Gibbs equations were employed here to calculate the apparent standard thermodynamic quantities for the dissolution and mixing processes of this drug in these aqueous mixtures. Inverse Kirkwood–Buff integrals were employed to calculate the preferential solvation parameters of meloxicam by NMP in all mixtures. Meloxicam equilibrium solubility increased with increasing temperature, and maximal solubilities were observed in neat NMP at all temperatures. The mole fraction solubility of meloxicam increased from 1.137 × 10–6 in neat water to 3.639 × 10–3 in neat NMP at 298.15 K. The Jouyban–Acree model correlated the meloxicam solubility in these mixtures very well. Dissolution processes were endothermic and entropy-driven in all cases, except in neat water, where nonenthalpy- nor entropy-driven was observed. Apparent Gibbs energies of dissolution varied from 34.35 kJ·mol–1 in pure water to 7.99 kJ·mol–1 in pure NMP at a mean harmonic temperature of 303.0 K. A nonlinear enthalpy–entropy relationship was observed in the plot of dissolution enthalpy vs dissolution Gibbs energy. Meloxicam is preferentially hydrated in water-rich mixtures but preferentially solvated by NMP in the composition interval of 0.16 < x1 < 1.00.

1. Introduction

Meloxicam (IUPAC name: 4-hydroxy-2-methyl-N-(5-methyl-2-thiazolyl)-2H-1,2-benzothiazine-3-carboxamide-1,1-dioxide, molar mass 351.40 g·mol–1, CAS number: 71125-38-7, PubChem CID: 54677470, molecular structure shown in Figure 1) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used commonly for pain and inflammatory treatments.1 Regarding its mechanism of action, meloxicam inhibits the cyclooxygenase (COX) synthesis, which is the enzyme responsible for converting arachidonic acid into prostaglandin H2. This is the first step in the synthesis of prostaglandins, which, in turn, are the mediators of inflammation processes. Meloxicam exhibits, especially at its low therapeutic dose, selective inhibition of COX-2 over COX-1.2−5 It is commercially available as tablets and oral suspensions.5 Meloxicam exhibits very low aqueous solubility,1 which influences negatively the in vivo dissolution rates, affecting, in turn, its pharmacological performance. Moreover, because of its very low aqueous solubility, the development of pharmaceutical liquid dosage forms in solution, like oral or injectable products, is not easy at the industrial level. For this reason, some investigations have been performed and reported to increase the aqueous equilibrium solubility of this drug. The main relevant strategy was based in the use of some commonly used pharmaceutical cosolvents, which have recently been summarized.6 Moreover, several other aqueous mixtures, involving different cosolvents, including choline-based deep eutectic solvents, have also been studied and reported.7−12 It is worth noting that very good meloxicam solubility-increasing effects have been reported, reaching more than 1000-fold in some cases, like those obtained with Carbitol (1144 times),9N-methylformamide (NMF) (1399 times),6 dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (6956 times),12 and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) (11,233 times).9

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of meloxicam.

N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, IUPAC name: 1-methylpyrrolidin-2-one, molar mass 99.13 g·mol–1, CAS number 872-50-4, molecular structure shown in Figure 2) is a colorless liquid, which is miscible with water, as well as with the most commonly used organic solvents.13−15 It is a dipolar aprotic solvent widely used in the petrochemical and plastics industries. This is because of its nonvolatility and very good performance for dissolving diverse materials. Particularly, it is used for recovering some hydrocarbons that are generated during the processing of petrochemicals and is also used to absorb hydrogen sulfide from sour gas.16 Owing to its very good solubilization properties, NMP has been used for dissolving a wide range of polymers applied in the surface treatment of textiles, resins, and metal-coated plastics. At the pharmaceutical-industrial level, NMP is used in the design and formulation of different liquid medicines intended for oral and transdermal delivery routes. Detailed information about the pharmaceutical uses of NMP has been summarized earlier in the literature.17 NMP has been used for analyzing the enhancement of aqueous phase transdermal transport.18 Moreover, NMP has recently been evaluated as an enhancer for facilitating the administration of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 when a rabbit model was studied.19

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone.

Aqueous mixtures of NMP are also widely used for theoretical and practical purposes. For this reason, different physicochemical properties of NMP–aqueous mixtures have been reported by several research groups to inside the structural aspects of these binary mixtures.20−25

Furthermore, some aqueous mixtures of NMP have been analyzed in cosolvency studies for increasing the equilibrium solubility of several drugs and drug-like compounds, as was compiled in the published literature.17,26 The specific compounds include terephthalic acid,27 sebacic acid,28,29 1,12-decanedioic acid, 1-naphthoic acid,28,29 phenobarbital,28−30 griseofulvine,28,29 phenytoin,28,29,31 ketoprofen,28,29 estrone,28,29 testosterone,28,29 ibuprofen,28,29,32 amiodarone,28,29 carbendazim,28,29 2-phenoxypropionic acid,28,29 (2R)-2-[4-(7-chloroquinoxalin-2-yl)oxyphenoxy]propanoic acid (XK-469),28,29 a benzoylphenyl urea derivative,28,29 2-(2-thiophenyl)-4-azabenzoimidazole (PG-300995),28,29 clonazepam,30 diazepam,30 lamotrigine,30 acetaminophen,32 amiodarone·HCl,33 celecoxib,34 6-methyl-2-thiouracil,35 ketoconazole,36 allopurinol,37 chloroxine,38d-histidine,39 5-aminosalicylic acid,40 bisacodyl,41 amoxicillin,42 5-nitrofurazone,43 biapenem,44 phenformin,45 griseofulvine,46 and sulfadiazine.47

The physicochemical data about the equilibrium solubility of drugs and drug-alike compounds in aqueous–cosolvent binary mixtures, as well as the deep understanding of the underlying drugs’ dissolution mechanisms, are very important for pharmaceutical and chemical scientists. Hence, the measured, reported, and analyzed drug equilibrium solubility values in multicomponent vehicles expand the existing solubility databases, which is both useful for practical and theoretical purposes in the pharmaceutical and/or chemical industries48−51 and also for testing the limitations and possible applications of newly developed predictive mathematical expressions.

Therefore, the main aims of this experimental research were as follows: to (i) determine and analyze the effects of both the mixtures’ composition and temperature on the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures; (ii) correlate the equilibrium solubility data with some well-known thermodynamic models; (iii) calculate the apparent standard dissolution and mixing thermodynamic parameters like Gibbs energy, enthalpy, and entropy; and (iv) calculate the preferential solvation parameters of meloxicam by NMP in binary mixtures prepared from NMP and water. Therefore, this research continues the meloxicam solubility subject that has been reported in other aqueous binary cosolvent systems of pharmaceutical relevance.6−12,52,53

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Meloxicam (obtained from Technodrugs & Intermediates PVT LTD, component 3, with purity > 0.995 in mass fraction), NMP (obtained from Panreac, component 1, with purity > 0.990 in mass fraction), and distilled water with a conductivity of <2 μS·cm–1 (component 2) were used in the solubility studies.

2.2. Preparation of Solvent Mixtures

All {NMP (1) + water (2)} binary solvent mixtures were prepared gravimetrically by means of an Ohaus Pioneer TM PA214 analytical balance of sensitivity ± 0.1 mg in quantities of 50.00 g. The mole fractions of NMP varied by 0.10 steps from x1 = 0.10 to x1 = 0.90.

2.3. Solubility Determination

Equilibrium meloxicam solubilities in {NMP (1) + water (2)} binary solvent mixtures and neat NMP were determined using the classical shake-flask method,54 followed by UV-spectrophotometric analysis, as follows: An excess amount of meloxicam was added to 50.00 g of each binary solvent mixture or neat NMP in dark glass pharmaceutical flasks of 60 cm3. The stoppered flasks were put in an ultrasonic bath (Elma E60H Elmasonic) for 15 min and later were transferred to thermostatic mechanical shakers (Julabo SW23, Germany) or recirculating thermostatic baths (Neslab RTE 10 Digital One Thermo Electron Company) kept at T = 313.15 K during at least 4 days to ensure that the drug saturation had been achieved at this temperature in all of the solvent systems. After that, all of the supernatant solutions were isothermally filtered (Millipore Corp. Swinnex-13) to remove undissolved meloxicam particles before sampling for composition analysis at saturation. Meloxicam concentrations were determined after appropriate gravimetric dilution of the saturated solutions with a 0.10 mol·dm–3 aqueous NaOH by measuring the UV light absorbance at the maximum absorbance wavelength, λmax = 361 nm (UV/VIS BioMate 3 Thermo Electron Company spectrophotometer), followed by interpolation from a previously validated UV-spectrophotometric gravimetric calibration curve prepared in 0.10 mol·dm–3 aqueous NaOH. The respective linear equation was: Absorbance = 0.0073 + 52.508·C, where C is the meloxicam concentration expressed as μg·g–1. After all of these stages, the temperature of thermostatic baths was decreased from T = (313.15 to 308.15) K, allowing the meloxicam excess precipitation for 2 days. Later, the same stages mentioned above were followed to determine the new meloxicam concentrations at saturation. All of these procedures were performed successively in steps of 5.0 K until the solid–liquid equilibrium was achieved at T = 293.15 K. All of the meloxicam solubility experiments were performed at least three times, and the respective results were averaged. The density of every saturated solution was measured by means of a digital density meter (DMA 45 Anton Paar, Austria) connected to a recirculating thermostatic bath (Neslab RTE 10 Digital One Thermo Electron Company) kept at the respective temperature to transform the obtained gravimetric solubility values into those expressed in volumetric concentration scales. The density meter was calibrated at every studied temperature using air and water as standards, as indicated in the respective instructions manual.55

2.4. Solid-Phase Analyses

2.4.1. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

To determine the crystal nature of the solid meloxicam samples, both before and after the drug saturation in neat water, in the binary mixture of x1 = 0.50, and in neat NMP, the respective X-ray powder diffraction analyses were performed (PANalytical Xpert Pro X-ray diffractometer). This equipment is provided with Cu Kα radiation λ = 1.5418 Å. Generator setting: 40 kV and 40 mA and Bragg–Brentano geometry. Respective data were collected at 2θ from 5 to 70° and an angle variation of 0.02° with a detector data acquisition time of 9.46 min. Measurements were performed at room temperature.

2.4.2. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

Additionally to XRD analyses, to evaluate and confirm the nature of the solid meloxicam samples, both before and after the drug saturation in neat water, in the binary mixture of x1 = 0.50, and in neat NMP, FTIR analyses were also performed. The meloxicam solid samples were ground with quantities of pure potassium bromide varying from 10 to 100 times its bulk. Later, the resulting mixtures were pressed into discs using a special mold and a manual hydraulic press (Specac). The respective IR spectra were obtained in an FTIR spectrophotometer (IRAffinity-1, Shimadzu, Japan).

2.5. Mathematical and Statistical Calculations

All of the statistical calculations and mathematical correlations were performed using different tools of MS Excel and TableCurve 2D v5.01 software, as required.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Mole Fraction and the Molarity Solubility of Meloxicam

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the obtained experimental equilibrium solubilities of meloxicam in all {NMP (1) + water (2)} systems, as expressed in mole fraction and molarity (mol·dm–3), respectively, at different temperatures and mixture compositions. It is important to note that the solubility values in neat water were taken from Delgado et al.52 If the mole fraction scale is considered, at T = 298.15 K, Table 1 shows that the meloxicam solubility increased 32,006 times from x3 = 1.137 × 10–6 in neat water to x3 = 3.639 × 10–2 in neat NMP, where maximum solubility is obtained at this temperature. A comparison of meloxicam equilibrium solubility in neat water has been reported and discussed earlier in our previous communication.6 However, up to the best of our knowledge, solubility values of meloxicam in aqueous mixtures of NMP or neat NMP have not been reported, and therefore, no more comparisons are possible.

Table 1. Experimental Mole Fraction Solubility (x3) of Meloxicam in {N-Methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + Water (2)} Mixtures at Five Temperatures from T = (293.15 to 313.15) K and p = 96 kPaa,b.

|

T/Kb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1a,b | 293.15 | 298.15 | 303.15 | 308.15 | 313.15 |

| 0.000c | 1.088 × 10–6 | 1.137 × 10–6 | 1.187 × 10–6 | 1.262 × 10–6 | 1.329 × 10–6 |

| 0.100 | 1.325 × 10–5 | 1.553 × 10–5 | 1.864 × 10–5 | 2.314 × 10–5 | 2.711 × 10–5 |

| 0.200 | 1.021 × 10–4 | 1.194 × 10–4 | 1.389 × 10–4 | 1.664 × 10–4 | 1.954 × 10–4 |

| 0.300 | 5.107 × 10–4 | 5.962 × 10–4 | 6.671 × 10–4 | 7.816 × 10–4 | 9.011 × 10–4 |

| 0.400 | 1.830 × 10–3 | 2.061 × 10–3 | 2.254 × 10–3 | 2.589 × 10–3 | 2.888 × 10–3 |

| 0.500 | 4.746 × 10–3 | 5.174 × 10–3 | 5.717 × 10–3 | 6.369 × 10–3 | 6.942 × 10–3 |

| 0.600 | 8.420 × 10–3 | 9.629 × 10–3 | 1.079 × 10–2 | 1.226 × 10–2 | 1.339 × 10–2 |

| 0.700 | 1.121 × 10–2 | 1.312 × 10–2 | 1.607 × 10–2 | 1.908 × 10–2 | 2.191 × 10–2 |

| 0.800 | 1.682 × 10–2 | 1.938 × 10–2 | 2.254 × 10–2 | 2.730 × 10–2 | 3.122 × 10–2 |

| 0.900 | 2.529 × 10–2 | 2.887 × 10–2 | 3.318 × 10–2 | 3.792 × 10–2 | 4.176 × 10–2 |

| 1.000 | 3.189 × 10–2 | 3.639 × 10–2 | 4.159 × 10–2 | 4.923 × 10–2 | 5.463 × 10–2 |

| idealc | 2.607 × 10–3 | 3.079 × 10–3 | 3.627 × 10–3 | 4.260 × 10–3 | 4.991 × 10–3 |

p is the atmospheric pressure in Bogotá, Colombia. x1 is the mole fraction of N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures free of meloxicam (3). Mean uncertainty in x1 is u(x1) = 0.0005.

Standard uncertainty in p is u(p) = 3.0 kPa. Average relative uncertainty in x3 is ur(x3) = 0.025. Standard uncertainty in T is u(T) = 0.10 K.

Data taken from Delgado et al.52

Table 2. Experimental Molar Solubility (C, mol·dm–3) of Meloxicam in {N-Methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + Water (2)} Mixtures at Five Temperatures from T = (293.15 to 313.15) K and p = 96 kPaa,b.

|

T/Kb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1a,b | 293.15 | 298.15 | 303.15 | 308.15 | 313.15 |

| 0.000c | 6.027 × 10–5 | 6.290 × 10–5 | 6.557 × 10–5 | 6.962 × 10–5 | 7.319 × 10–5 |

| 0.100 | 5.225 × 10–4 | 6.105 × 10–4 | 7.302 × 10–4 | 9.034 × 10–4 | 1.055 × 10–3 |

| 0.200 | 3.119 × 10–3 | 3.633 × 10–3 | 4.211 × 10–3 | 5.022 × 10–3 | 5.873 × 10–3 |

| 0.300 | 1.266 × 10–2 | 1.471 × 10–2 | 1.638 × 10–2 | 1.909 × 10–2 | 2.190 × 10–2 |

| 0.400 | 3.787 × 10–2 | 4.242 × 10–2 | 4.615 × 10–2 | 5.270 × 10–2 | 5.847 × 10–2 |

| 0.500 | 8.369 × 10–2 | 9.076 × 10–2 | 9.966 × 10–2 | 0.1103 | 0.1195 |

| 0.600 | 0.1290 | 0.1466 | 0.1631 | 0.1836 | 0.1991 |

| 0.700 | 0.1524 | 0.1769 | 0.2141 | 0.2519 | 0.2858 |

| 0.800 | 0.2043 | 0.2333 | 0.2684 | 0.3212 | 0.3628 |

| 0.900 | 0.2763 | 0.3122 | 0.3547 | 0.4019 | 0.4374 |

| 1.000 | 0.3192 | 0.3597 | 0.4065 | 0.4749 | 0.5194 |

p is the atmospheric pressure in Bogotá, Colombia. x1 is the mole fraction of N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures free of meloxicam (3). Mean uncertainty in x1 is u(x1) = 0.0005.

Standard uncertainty in p is u(p) = 3.0 kPa. Average relative uncertainty in C is ur(C) = 0.025. Standard uncertainty in T is u(T) = 0.10 K.

Data taken from Delgado et al.52

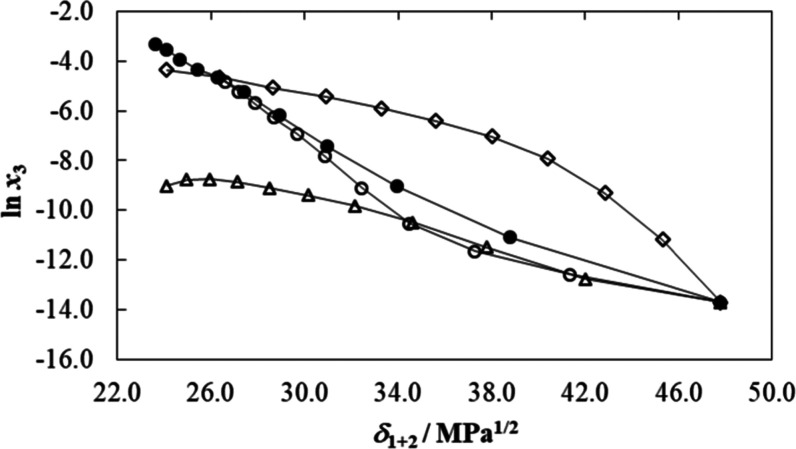

Figure 3 depicts the logarithmic solubility profiles of meloxicam as a function of the Hildebrand solubility parameters (δ1+2) of {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures at T = 298.15 K. As has widely been described in the literature, δ1+2 is a very important polarity descriptor of aqueous and nonaqueous binary cosolvent mixtures.48−51 The values of this descriptor were calculated considering the Hildebrand solubility parameter of every pure solvent (δ1 = 23.6 MPa1/2 for NMP and δ2 = 47.8 MPa1/2 for water)56,57 and its volume fraction (fi) as49,58

| 1 |

Figure 3.

Logarithmic mole fraction solubility of meloxicam (ln x3) as function of the Hildebrand solubility parameter in some {cosolvent (1) + water (2)} mixtures at T = 298.15 K. ●: N-Methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2); ○: dimethyl sulfoxide (1) + water (2);12 ◊: N,N-dimethylformamide (1) + water (2);6 and Δ: acetonitrile (1) + water (2).7

As observed in Figure 3, the solubility curve exhibited a maximum value in neat NMP, where δ1 is 23.6 MPa1/2. If only substance polarity is considered, every solute normally reaches its maximum solubility in solvent systems exhibiting a similar polarity index value.48,49 Thus, it is expected that the meloxicam δ3 value would be lower than 23.6 MPa1/2 at T = 298.15 K. However, the obtained solubility-based δ3 value is lower regarding the one reported earlier (δ3 = 32.1 MPa1/2)6 that was calculated by means of the Fedors’ groups contribution method.59 This large discrepancy between δ3 values could be attributed mainly to some specific drug solvation processes by NMP or water, which are not taken into account in Fedors’ calculations, in particular if the structural and complexing effects described for aqueous mixtures of NMP are considered.23,28,29

Otherwise, Figure 3 also compares the logarithmic solubility of meloxicam as a function of δ1+2 in some other aqueous–aprotic cosolvent mixtures, namely, {NMP (1) + water (2)}, {DMSO (1) + water (2)},12 {DMF (1) + water (2)},6 and {acetonitrile (1) + water (2)}7 mixtures at 298.15 K. It is worth noting that meloxicam solubilities are highest in {DMF (1) + water (2)} mixtures, followed by {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures, in turn, followed by {DMSO (1) + water (2)} mixtures and the lowest in {acetonitrile (1) + water (2)} mixtures, when δ1+2 > 26.5 MPa1/2. Otherwise, in mixtures of δ1+2 < 26.5 MPa1/2, the meloxicam solubilities are highest in NMP–aqueous mixtures, followed by DMF–aqueous mixtures, and lowest in acetonitrile–aqueous mixtures. Observed behaviors demonstrate that meloxicam solubility depends not exclusively on the mixtures’ polarity but also on some other physicochemical properties of both the solute and solvent systems.

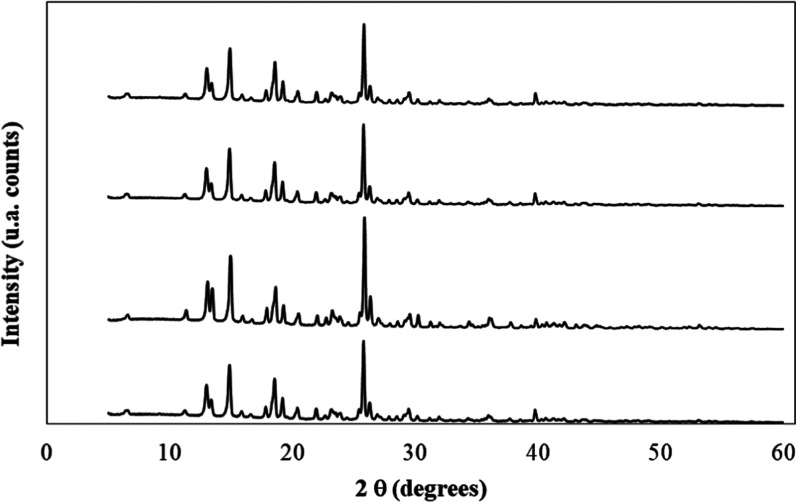

3.2. Solid-Phase Analyses

X-ray diffraction spectra of meloxicam, as an original sample and after saturation in neat water, neat NMP, and the aqueous mixture of x1 = 0.50 are shown in Figure 4. Because of the high similarity among all spectra, it could be concluded that possible changes in the crystalline form of meloxicam are not observed after its dissolution and saturation in these {NMP (1) + water (2)} cosolvent systems. Moreover, all of the XRD spectra obtained in this research are very similar to the one reported in the literature for polymorph I of meloxicam.52,60−63 Moreover, FTIR spectra of solid meloxicam samples shown in Figure 5 are also coincident with those reported in the literature, which allowed to indicate that all bottom-solid phases obtained after meloxicam saturation have the same nature as the original untreated sample.63−66 Therefore, as indicated, meloxicam did not suffer crystal polymorphic transitions or solvate formation after its saturation in these experiments.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction spectra of meloxicam. From top to bottom: crystallized in water, crystallized in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} (x1 = 0.50) mixture, crystallized in N-methyl-pyrrolidone, and the original untreated sample.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of meloxicam. From top to bottom: original untreated sample, crystallized in N-methyl-pyrrolidone, crystallized in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} (x1 = 0.50) mixture, and crystallized in water.

3.3. Activity Coefficients of Meloxicam in Mixed Solvents

Table 3 summarizes the obtained asymmetrical-based activity coefficients (γ3) of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures. These γ3 values were calculated as the (x3id/x3) quotient from the experimental (x3) and ideal (x3id) solubilities summarized in Table 1. Literature ideal solubilities were calculated as shown in the literature,67 using the following fusion values, Tfus = 536.7 (±0.7) K and ΔfusH = 43.9 (±0.4) kJ·mol–1,52 and assuming the respective ΔCp value as similar to the entropy of fusion. As observed, γ3 values vary from 2708 in neat water (where the lower meloxicam solubility is observed) to 8.46 × 10–2 in neat NMP at T = 298.15 K (where the maximum meloxicam solubility is observed at this temperature). It is worth noting that at all temperatures, meloxicam exhibits γ3 values higher than the unity in neat water and the mixtures of x1 ≤ 0.40 but γ3 values lower than the unity in the solvent systems of 0.50 ≤ x1 ≤ 1.00.

Table 3. Activity Coefficients of Meloxicam in {N-Methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + Water (2)} Mixtures at Five Temperatures from T = (293.15 to 313.15) K and p = 96 kPaa,b.

|

T/Kb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1a,b | 293.15 | 298.15 | 303.15 | 308.15 | 313.15 |

| 0.000c | 2396 | 2708 | 3055 | 3376 | 3755 |

| 0.100 | 197 | 198 | 195 | 184 | 184 |

| 0.200 | 25.5 | 25.8 | 26.1 | 25.6 | 25.5 |

| 0.300 | 5.11 | 5.16 | 5.44 | 5.45 | 5.54 |

| 0.400 | 1.42 | 1.49 | 1.61 | 1.65 | 1.73 |

| 0.500 | 0.549 | 0.595 | 0.634 | 0.669 | 0.719 |

| 0.600 | 0.310 | 0.320 | 0.336 | 0.348 | 0.373 |

| 0.700 | 0.233 | 0.235 | 0.226 | 0.223 | 0.228 |

| 0.800 | 0.155 | 0.159 | 0.161 | 0.156 | 0.160 |

| 0.900 | 0.103 | 0.107 | 0.109 | 0.112 | 0.120 |

| 1.000 | 8.18 × 10–2 | 8.46 × 10–2 | 8.72 × 10–2 | 8.65 × 10–2 | 9.13 × 10–2 |

p is the atmospheric pressure in Bogotá, Colombia. x1 is the mole fraction of N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures free of meloxicam (3). Mean uncertainty in x1 is u(x1) = 0.0005.

Standard uncertainty in p is u(p) = 3.0 kPa. Average relative uncertainty in γ3 is ur(γ3) = 0.028. Standard uncertainty in T is u(T) = 0.10 K.

Data taken from Delgado et al.52

Equation 2 allows a rough estimate of the energetic magnitudes involved in the solute–solvent intermolecular interactions from the γ3 values observed in these mixtures.68

| 2 |

Subscript 1 stands for the solvent system under consideration, which corresponds to both neat solvents or all of the aqueous–NMP binary mixtures, ess,e33, and es3 represent the solvent–solvent, solute–solute, and solvent–solute interaction energies, respectively. However, it is important to keep in mind that, in absolute ternary systems, like NMP–water–meloxicam, some water interactions are also present. These interactions could also play an important role in drug solubility and dissolution. V3 denotes the molar volume of meloxicam as a supercooled liquid, whereas φs denotes the volume fraction of the solvent system. For low x3 solubility values, V3φs2/RT may be considered constant despite the respective solvent system. Hence, γ3 values would depend mainly on ess,e33, and es3 magnitudes.68 As well known, ess and e33 are unfavorable for the drug solubility and dissolution rate, whereas es3 is favorable for increasing the respective meloxicam solubility and dissolution rate. As a first approach, the contribution of e33 could be considered as a constant value regardless the solvent system. Hence, from a qualitative point of view, based on the energetic quantities described in eq 2, the following description could be established: because in these mixtures, ess is the highest in neat water (δ2 = 47.8 MPa1/2) and the lowest in neat NMP (δ1 = 23.6 MPa1/2),56,57 then, neat water and water-rich mixtures (which exhibit γ3 values higher than 2300) would imply high ess and low es3 values, whereas in NMP-rich mixtures (which exhibit γ3 values near the unity and even lower), the ess values are relatively low, and, in turn, the es3 values would be high. Thus, higher meloxicam solvation by NMP in NMP-rich mixtures is expected.

3.4. Meloxicam Solubility Modeling

Modeling investigations on the solubility data of pharmaceuticals enable us to better understand the solubilization process of drugs in the solutions, to predict the unmeasured solubility data using interpolation technique, to detect possible outliers for their redetermination, and also to report the solubility data using a small number of model constants. Among the available approaches for the calculation of modeling the drug solubility data in binary solvent mixtures at isothermal conditions or at different temperatures,69,70 the Yalkowsky model is the simplest one,71 which requires only the experimental drug solubility data in the monosolvents to calculate the drug solubility in other solvent mixtures compositions. It is commonly presented as

| 3 |

where x3–(1+2) denotes the mole fraction solubility of meloxicam in the binary solvent mixtures, x3(1) denotes the mole fraction solubility of meloxicam in NMP (component 1), x3(2) denotes the mole fraction solubility of meloxicam in water (component 2), and x1 and x2 are the mole fractions of NMP (1) and water (2) in the solvent mixtures in the absence of meloxicam (3). Thus, the obtained mean percentage deviation (MPD) values when calculating the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures at T = (293.15, 298.15, 303.15, 308.15 and 313.15) K using this model were 69.8, 70.3, 70.9, 71.2, and 71.6%, respectively, with the overall MPD of 70.8%. The numerical values of the MPD were computed using

| 4 |

where N is the number of experimental solubility data points. To obtain the model constants, the minimization of the (ln x3calcd – ln x3)2 term was used employing MS Excel or other common packages. The “Enter” function was used to select the independent parameters considering the probability of less than 0.05.

As mentioned above, eq 3 is capable of estimating drug solubility in mixtures at constant T using only drug solubility data in the monosolvents at T. However, we extended its capability to various temperatures by combining the van’t Hoff and log-linear models as

| 5 |

in which A and B terms are the respective model constants.72 Thus, the trained model for describing the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures is given as

| 6 |

which resulted in an MPD of 70.9% (N = 55).

The Yalkowsky model does not consider the interactions by mixing observed in the real solutions. Nevertheless, the Jouyban–Acree model considers these interaction terms (as Ji terms) to provide the most accurate equilibrium solubility data in binary solvent mixtures at various temperatures. The basic version of the Jouyban–Acree model is given as69

| 7 |

where the Ji term is the model constants, which is computed using a nonintercept least-squares analysis.51 Accordingly, the generated solubility values of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} were fitted to eq 7, and the obtained trained model is given as

| 8 |

The F value of eq 8 was 8131.7, and the correlation and the model constants were all significant with p < 0.0005. Equation 8 is valid for calculating the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures at various temperatures using the equilibrium solubility data of meloxicam in both monosolvents at each temperature. The obtained MPD for the back-calculated solubility data of meloxicam using eq 8 was 9.5%.

Although eq 8 provided an accurate correlation for equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures, it requires x3(1),T and x3(2),T values at any temperature of interest to compute the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in the mixed solvents. It is important to note that x3(1),T and x3(2),T correspond to the mole fraction solubilities of meloxicam in pure NMP and pure water at every temperature, respectively. However, it is possible to combine the trained version of eq 5 with eq 7 to provide a full predictive model as follows

|

9 |

Equation 9 calculates the solubilities of meloxicam in these {NMP (1) + water (2)} binary mixtures at various temperatures with an MPD of 9.7%. In practical applications of eq 9, it is possible to train the model employing a minimum number of seven experimental solubility data points and then predict the rest of the required solubility data in any solvent mixture composition and temperature of interest, as has been exemplified in a previous communication.73 When the model was trained with the meloxicam solubility data in NMP and water at T = (293.15 and 313.15) K (the lowest and highest temperatures, respectively) and in mixtures of x1 = 0.30, 0.50, and 0.70 at T = 298.15 K (totally 7 data points), the rest of solubility data points were predicted, observing an MPD value of 11.9% (N = 48).

In previous research,74 generally trained versions of the Jouyban–Acree–Abraham and Jouyban–Acree–Hansen models were reported for predicting the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in various binary solvent mixtures. These models are

|

10 |

and

|

11 |

where c, e, s, a, b, and v are the Abraham solvents’ coefficients and δd1, δp1, and δh1 and δd2, δp2, and δh2 are the Hansen parameters for the solvents 1 and 2, respectively.74Equations 10 and 11 estimated the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures with MPD values of 71.4 and 57.5%, respectively. Although the estimation errors are relatively large, these equations only require the drug solubility data in neat solvents. By including further drug solubility data sets in the training processes of eqs 10 and 11, more accurate predictions could be achieved.

To sum up this section, we used the log-linear model of Yalkowsky (as the simplest model requiring only the drug solubility data in the monosolvents)71 and its extended version for various temperatures,72 the Jouyban–Acree model (as the most accurate70 and reliable model)69 and its extended versions26,51,69,74 to provide a full picture of correlation/prediction of the solubility of meloxicam in a mixed solvent system.

3.5. Apparent Thermodynamic Functions of Meloxicam Dissolution Processes

All apparent standard thermodynamic quantities relative to dissolution processes of meloxicam in NMP–aqueous mixtures were determined at the mean harmonic temperature, Thm = 303.0 K, which was obtained by means of eq 12.75

| 12 |

where n = 5 is the number of temperatures under study from T = (293.15–313.15) K. The apparent standard enthalpy changes of meloxicam dissolution processes (ΔsolnH°) were obtained by means of the modified van’t Hoff equation, as shown in eq 13 76

| 13 |

The apparent standard Gibbs energy changes describing the meloxicam dissolution processes (ΔsolnG°) were calculated according to Krug et al. by means of76,77

| 14 |

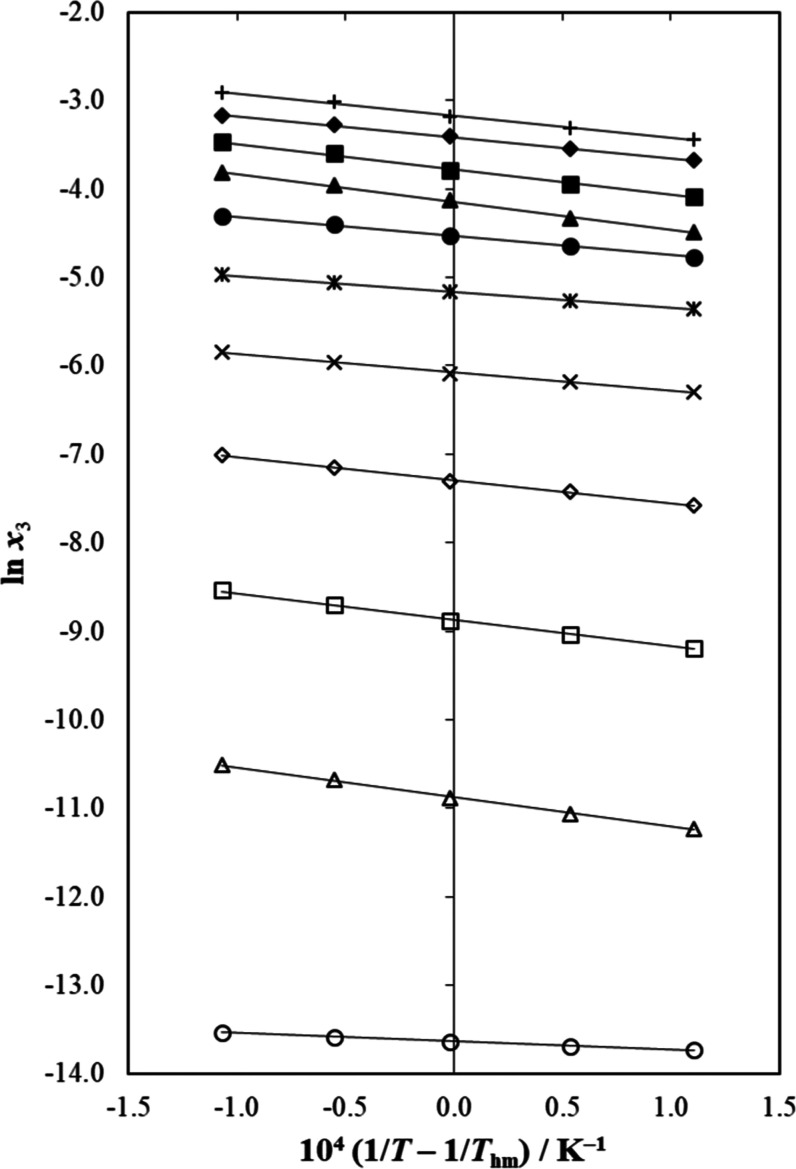

Used intercepts of eq 14 were those obtained from the linear regressions of ln x3 as a function of (1/T – 1/Thm). As visual help, Figure 6 depicts the meloxicam equilibrium solubility behavior in all of the {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures, as well as in both neat solvents. Linear regressions with r2 > 0.996 were observed in all of these NMP–aqueous solvent systems.78−80

Figure 6.

van’t Hoff plot of the solubility of meloxicam (3) in {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} solvent systems. ○: x1 = 0.00 (neat water), Δ: x1 = 0.10, □: x1 = 0.20, ◊: x1 = 0.30, ×: x1 = 0.40, *: x1 = 0.50, ●: x1 = 0.60, ▲: x1 = 0.70, ■: x1 = 0.80, ◆: x1 = 0.90, and +: x1 = 0.10 (neat N-methyl-pyrrolidone).

Finally, the apparent standard entropy changes of the meloxicam dissolution processes (ΔsolnS°) were calculated from the respective ΔsolnH° and ΔsolnG° values by means of77

| 15 |

Table 4 summarizes the apparent standard thermodynamic quantities relative to the dissolution processes of meloxicam in all of the {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures at Thm = 303.0 K. This table also includes those quantities associated with the meloxicam dissolution processes in neat water and NMP. Apparent standard dissolution thermodynamic quantities in neat water were also taken from the literature.52 As expected, the apparent standard Gibbs energies as well as the apparent enthalpies of dissolution of meloxicam in all of these NMP–aqueous systems were positive in every case. It is important to keep in mind that ΔsolnG° values are positive because mole fraction solubilities of meloxicam are lower than 1.0 in all cases, and thus, the respective Krug et al. intercepts are negative in all cases, as shown in Figure 6. Although ΔsolnG° values are positive, the dissolution processes of meloxicam are always spontaneous until the drug saturation is reached in every case. In a similar way, the apparent standard dissolution entropies were positive in almost all cases, except in neat water. Thus, the global dissolution processes of meloxicam are endothermic and entropy-driven in the composition interval of 0.10 ≤ x1 ≤ 1.00, whereas, in neat water, neither entropy- nor enthalpy-driven is observed. ΔsolnG° values decrease continuously from neat water to reach the lowest value in neat NMP. ΔsolnH° increases from neat water to reach the highest value in the mixture of x1 = 0.10, and it decreases with the NMP proportion to reach a new minimum in the mixture of x1 = 0.50. After this composition, it increases to reach a new maximum in the mixture of x1 = 0.70, followed by a decrease in the mixture of x1 = 0.90. ΔsolnS° values increase from a negative value in neat water to reach the maximum positive value in the mixture of x1 = 0.70, and later, they remain almost constant with the NMP proportion. As observed, the lowest ΔsolnH° and ΔsolnS° values are obtained in neat water (x1 = 0.00). Negative apparent dissolution entropy observed in neat water could be a consequence of hydrophobic hydration effects around the nonpolar methyl and phenylene groups of meloxicam (Figure 1). On the other hand, the relative magnitude contributions by enthalpy (ζH) and entropy (ζTS) toward the global drug dissolution processes are given by the following equations81

| 16 |

| 17 |

Table 4. Apparent Thermodynamic Functions Relative to Dissolution Processes of Meloxicam (3) in {N-Methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + Water (2)} Mixtures at Thm = 303.0 K and p = 96 kPaa,b.

| x1a,b | ΔsolnG°/kJ·mol–1b | ΔsolnH°/kJ·mol–1b | ΔsolnS°/J·mol–1·K–1b | TΔsolnS°/kJ·mol–1b | ζHc | ζTSc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.000d | 34.35 | 7.69 | –87.99 | –26.66 | 0.224 | 0.776 |

| 0.100 | 27.40 | 27.92 | 1.71 | 0.52 | 0.982 | 0.018 |

| 0.200 | 22.34 | 24.89 | 8.41 | 2.55 | 0.907 | 0.093 |

| 0.300 | 18.38 | 21.46 | 10.18 | 3.08 | 0.874 | 0.126 |

| 0.400 | 15.31 | 17.40 | 6.89 | 2.09 | 0.893 | 0.107 |

| 0.500 | 13.00 | 14.78 | 5.85 | 1.77 | 0.893 | 0.107 |

| 0.600 | 11.42 | 17.87 | 21.28 | 6.45 | 0.735 | 0.265 |

| 0.700 | 10.45 | 26.20 | 51.98 | 15.75 | 0.625 | 0.375 |

| 0.800 | 9.52 | 24.10 | 48.13 | 14.58 | 0.623 | 0.377 |

| 0.900 | 8.60 | 19.49 | 35.93 | 10.89 | 0.642 | 0.358 |

| 1.000 | 7.99 | 21.05 | 43.10 | 13.06 | 0.617 | 0.383 |

| ideald | 14.16 | 24.78 | 35.03 | 10.61 | 0.700 | 0.300 |

p is the atmospheric pressure in Bogotá, Colombia. x1 is the mole fraction of N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures free of meloxicam (3). Mean uncertainty in x1 is u(x1) = 0.0005.

Standard uncertainty in Thm is u(Thm) = 0.13 K. Standard uncertainty in p is u(p) = 3.0 kPa. Average relative standard uncertainty in apparent thermodynamic quantities of real dissolution processes are ur(ΔsolnG°) = 0.028, ur(ΔsolnH°) = 0.037, ur(ΔsolnS°) = 0.047, and ur(TΔsolnS°) = 0.047.

ζH and ζTS are the relative contributions by enthalpy and entropy toward apparent Gibbs energy of dissolution.

Data taken from Delgado et al.52

As observed in Table 4, the main contributing thermodynamic function to the positive apparent standard molar Gibbs energies of meloxicam dissolution processes is the positive enthalpy. This demonstrates the energetic predominance in almost all of these dissolution processes, except in neat water, where ζH = 0.224, and thus, the entropy is the dominant function in this neat solvent.

3.6. Apparent Thermodynamic Quantities of Meloxicam Mixing Processes

The overall dissolution processes of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} solvent systems may be represented by the following hypothetical stages

Here, the hypothetical stages are as follows: (i) the heating and fusion of meloxicam at Tfus = 536.7 K, (ii) the cooling of the liquid meloxicam to the considered temperature (Thm = 303.0 K), and (iii) the subsequent mixing of both the hypothetical supercooled liquid meloxicam and the {NMP (1) + water (2)} liquid solvent system at Thm = 303.0 K.82 This treatment allowed the calculation of the individual thermodynamic contributions by fusion and mixing toward the overall meloxicam dissolution processes by means of the following expressions

| 18 |

| 19 |

where ΔfusHThm and ΔfusSThm represent the thermodynamic quantities relative to meloxicam melting and its cooling at Thm = 303.0 K, which, in turn, were calculated using36

| 20 |

| 21 |

where ΔCp denotes the difference in heat capacities of liquid and solid states of meloxicam at the temperature of melting (Tfus = 536.7 K). Owing to the difficulties found in experimental determination of ΔCp, the entropy of fusion (ΔfusS) is commonly used instead.36Table 5 summarizes the apparent standard thermodynamic quantities relative to mixing processes of the hypothetical supercooled liquid meloxicam with all of the aqueous–NMP mixtures and the neat solvents, water, and NMP, at Thm = 303.0 K. Apparent Gibbs energies of mixing are positive from neat water to the mixture of x1 = 0.40 because the experimental meloxicam solubilities are lower than ideal solubilities; on the contrary, they are negative from the mixture of x1 = 0.50 to neat NMP because the experimental meloxicam solubilities are higher than the ideal ones. The contributions of the thermodynamic quantities relative to the mixing process to the overall dissolution processes of meloxicam are variable depending on the mixtures’ composition. Thus, ΔmixH° are negative in water and the mixtures of 0.30 ≤ x1 ≤ 0.60 and 0.80 ≤ x1 ≤ 1.00 but positive in the mixtures of x1 = 0.10, 0.20 and 0.70. Moreover, ΔmixS° values are negative from neat water to the mixture of x1 = 0.60 but positive from the mixture of x1 = 0.70 to neat NMP. Thus, the mixing processes of meloxicam in neat water and the mixtures of 0.30 ≤ x1 ≤ 0.60 are enthalpy-driven because of the exothermic character exhibited (ΔmixH° < 0 and ΔmixS° < 0). In the mixtures of x1 = 0.10 and 0.20, neither enthalpy- nor entropy-driven is observed for mixing (ΔmixH° > 0 and ΔmixS° < 0). In the mixture of x1 = 0.70, the mixing process is entropy-driven (ΔmixH° > 0 and ΔmixS° > 0). Finally, in the interval of 0.80 ≤ x1 ≤ 1.00, both enthalpy- and entropy-driven are observed for mixing processes (ΔmixH° < 0 and ΔmixS° > 0). Furthermore, to compare the relative contributions by enthalpy (ζH) and entropy (ζTS) to the meloxicam mixing processes, two equations analogous to eqs 16 and 17 were employed. As observed, in water-rich mixtures (0.00 ≤ x1 ≤ 0.40) and the mixtures of x1 = 0.70 and 0.80, the main contributor to Gibbs energies of mixing is the entropy, whereas in the mixtures of x1 = 0.50, 0.60, 0.90, and neat NMP is the enthalpy.

Table 5. Apparent Thermodynamic Functions Relative to Mixing Processes of Meloxicam (3) in {N-Methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + Water (2)} Mixtures at Thm = 303.0 K and p = 96 kPaa,b.

| x1a,b | ΔmixG°/kJ·mol–1b | ΔmixH°/kJ·mol–1b | ΔmixS°/J·mol–1·K–1b | TΔmixS°/kJ·mol–1b | ζHc | ζTSc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.000 | 20.19 | –17.09 | –123.02 | –37.27 | 0.314 | 0.686 |

| 0.100 | 13.24 | 3.14 | –33.32 | –10.10 | 0.237 | 0.763 |

| 0.200 | 8.18 | 0.11 | –26.62 | –8.07 | 0.014 | 0.986 |

| 0.300 | 4.22 | –3.31 | –24.85 | –7.53 | 0.305 | 0.695 |

| 0.400 | 1.15 | –7.38 | –28.14 | –8.53 | 0.464 | 0.536 |

| 0.500 | –1.16 | –10.00 | –29.18 | –8.84 | 0.531 | 0.469 |

| 0.600 | –2.74 | –6.91 | –13.74 | –4.16 | 0.624 | 0.376 |

| 0.700 | –3.72 | 1.42 | 16.95 | 5.14 | 0.216 | 0.784 |

| 0.800 | –4.65 | –0.68 | 13.10 | 3.97 | 0.146 | 0.854 |

| 0.900 | –5.56 | –5.29 | 0.90 | 0.27 | 0.951 | 0.049 |

| 1.000 | –6.17 | –3.73 | 8.07 | 2.44 | 0.604 | 0.396 |

p is the atmospheric pressure in Bogotá, Colombia. x1 is the mole fraction of N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures free of meloxicam (3). Mean uncertainty in x1 is u(x1) = 0.0005.

Standard uncertainty in Thm is u(Thm) = 0.13 K. Standard uncertainty in p is u(p) = 3.0 kPa. Average relative standard uncertainty in apparent thermodynamic quantities of mixing processes are ur(ΔmixG°) = 0.031, ur(ΔmixH°) = 0.042, ur(ΔmixS°) = 0.052, and ur(TΔmixS°) = 0.052.

ζH and ζTS are the relative contributions by enthalpy and entropy toward the apparent Gibbs energy of mixing.

In aqueous binary mixtures, the net variation of ΔmixH° values, as the mixtures composition changes, depends on the contribution of different kinds of intermolecular interactions. Thus, the cavity formation in the solvent, which is required for accommodating the solute, is endothermic because some energy extent must be supplied against the respective solvent cohesive forces. This requirement diminishes the drug solubility in this medium, as mentioned above. Oppositely, the solvent–solute interactions, resulting mainly from van der Waals and Lewis acid–base interactions, are exothermic in nature. This last effect increases the meloxicam solubility, as also indicated before. Even more, the structuring of water molecules as “icebergs” around the phenylene ring and the methyl group of meloxicam (Figure 1) would contribute to lowering the net ΔmixH° to small or even negative values in water and water-rich mixtures.83 This event is clearly observed with meloxicam in aqueous–NMP mixtures, as shown in Table 5 for systems from neat water to the mixture of x1 = 0.60. However, the complexing effects of NMP could be contributing to increasing the meloxicam solubility, in particular in water-rich mixtures, as has already been described in the literature.28,29

3.7. Enthalpy–Entropy Compensation Analysis of Meloxicam

Extra-thermodynamic studies, especially those related to enthalpy–entropy compensation analyses, provide a powerful tool for the identification of similar mechanisms involved in physical and chemical processes implying similar organic compounds.84,85 In this way, some literature reports demonstrated nonlinear enthalpy–entropy compensation effects when studying the dissolution processes of many drugs in different aqueous–cosolvent mixtures. These physicochemical studies have usually been performed to identify and obtain insights into the main mechanisms involved in the cosolvent action for increasing or decreasing the drug solubility and dissolution rate, depending on the binary mixtures’ composition.86−88 As shown in Figure 7, meloxicam exhibits a nonlinear ΔsolnH° vs ΔsolnG° trend with negative slopes from neat water to the mixture of x1 = 0.10, from the mixture of x1 = 0.50 to x1 = 0.70, and from x1 = 0.90 to neat NMP, whereas in the interval of 0.10 ≤ x1 ≤ 0.50 and from x1 = 0.70 to 0.90, positive slopes are observed. In the first cases, the driving mechanism for transferring meloxicam from the most polar to the less solvent systems is entropy. First, from neat water to the mixture of x1 = 0.10, entropy could be associated with water molecules releasing from the icebergs existing around the nonpolar groups of meloxicam as a consequence of NMP addition to water. For the composition intervals exhibiting positive slopes, the drug transfer processes are driven by enthalpy. Nevertheless, it is not easy to identify the molecular events involved, owing to the complexity of aqueous–NMP mixtures, as indicated earlier.24,28,29

Figure 7.

Enthalpy–entropy compensation plot for the solubility of meloxicam (3) in {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures at Thm = 303.0 K. The points represent the mole fraction of N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures in the absence of meloxicam (3).

3.8. Preferential Solvation Analysis

The preferential solvation parameter of meloxicam (component 3) by NMP (component 1) in the {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures (δx1,3) is defined as

| 22 |

where x1,3L is the local mole fraction of NMP in the molecular environment of meloxicam and x1 is the bulk mole fraction of NMP in the initial aqueous–NMP mixture free of meloxicam. If δx1,3 values are positive, meloxicam would be preferentially solvated by NMP in these binary solvent mixtures, but if they are negative, meloxicam would be preferentially solvated by water in these mixtures. δx1,3 values were obtained by means of the inverse Kirkwood–Buff integral (IKBI) applied to every solvent component based on the following thermodynamic definitions89−91

| 23 |

with

| 24 |

| 25 |

| 26 |

In these equations, κT denotes the isothermal compressibility of the {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures. V̅1 and V̅2 denote the partial molar volumes of NMP and water in the mixtures. V̅3 denotes the partial molar volume of meloxicam in the respective dissolution. The function D corresponds to the first derivative of the variation of standard molar Gibbs energies of transfer of meloxicam from neat water to {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures with respect to the mole fraction of NMP in the mixtures, as defined in eq 27. The function Q involves the second derivative of the variation of excess molar Gibbs energy of mixing of NMP and water (G1+3Exc) with respect to the mole fraction of water in the mixtures, as defined in eq 28. Vcor denotes the correlation volume and r3 denotes the molecular radius of meloxicam. In turn, r3 is commonly calculated from eq 29, where NAv denotes the number of Avogadro.

| 27 |

| 28 |

| 29 |

The definitive Vcor value requires iterative calculation because it depends on the local mole fractions of NMP and water around the meloxicam molecules. Hence, this iteration process is performed by substituting δx1,3 and Vcor values in eqs 22, 23, and 26 to recalculate x1,3L until nonvariant values of Vcor are obtained.

Figure 8 depicts the apparent Gibbs energies of transfer of meloxicam from neat water to {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures (ΔtrG3,2→1+2°) at T = 298.15 K. These ΔtrG3,2→1+2 values were calculated from the mole fraction solubility data shown in Table 1 using

| 30 |

ΔtrG3,2→1+2° values were correlated according to the regular fourth degree polynomial presented as eq 31, obtaining the following parameters: adjusted r2 = 0.9997, typical error = 0.1435, and F value = 8570.

| 31 |

Figure 8.

Gibbs energy of transfer of meloxicam (3) from neat water (2) to {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures at T = 298.15 K.

The D values shown in Table 6 were calculated from the first derivative of eq 31 by considering the variation of NMP in the mixture composition in increasing x1 = 0.05 steps. Otherwise, Q, RTκT, V̅1, and V̅2 values of {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures at T = 298.15 K were taken from the literature.34

Table 6. Some Properties Associated with the Preferential Solvation of Meloxicam (3) in {N-Methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + Water (2)} Mixtures at T = 298.15 K.

| x1a | D/kJ·mol–1 | G1,3/cm3·mol–1 | G2,3/cm3·mol–1 | Vcor/cm3·mol–1 | 100 δx1,3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | –71.31 | –702.7 | –182.2 | 829 | 0.00 |

| 0.05 | –64.29 | –669.9 | –311.3 | 860 | –3.21 |

| 0.10 | –57.63 | –596.6 | –417.0 | 942 | –3.19 |

| 0.15 | –51.33 | –513.2 | –484.4 | 1061 | –0.64 |

| 0.20 | –45.42 | –438.6 | –519.2 | 1175 | 1.92 |

| 0.25 | –39.89 | –378.9 | –532.6 | 1273 | 3.70 |

| 0.30 | –34.76 | –332.9 | –533.5 | 1360 | 4.75 |

| 0.35 | –30.04 | –298.0 | –527.4 | 1437 | 5.27 |

| 0.40 | –25.73 | –271.3 | –517.0 | 1508 | 5.41 |

| 0.45 | –21.85 | –250.7 | –503.6 | 1575 | 5.28 |

| 0.50 | –18.40 | –234.5 | –487.7 | 1638 | 4.96 |

| 0.55 | –15.39 | –221.7 | –469.5 | 1699 | 4.49 |

| 0.60 | –12.84 | –211.6 | –449.4 | 1758 | 3.93 |

| 0.65 | –10.75 | –203.7 | –428.7 | 1815 | 3.34 |

| 0.70 | –9.13 | –197.7 | –409.5 | 1873 | 2.76 |

| 0.75 | –7.99 | –193.3 | –394.9 | 1930 | 2.24 |

| 0.80 | –7.33 | –190.1 | –388.5 | 1988 | 1.81 |

| 0.85 | –7.18 | –187.8 | –394.4 | 2046 | 1.44 |

| 0.90 | –7.54 | –186.0 | –417.8 | 2104 | 1.10 |

| 0.95 | –8.41 | –184.2 | –467.3 | 2161 | 0.69 |

| 1.00 | –9.81 | –181.8 | –563.4 | 2213 | 0.00 |

x1 is the mole fraction of N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) in the {N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2)} mixtures free of meloxicam (3).

Because V̅3 values are not available for meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures, they were considered here as invariant and equal to the one calculated based on the Fedors’ method, i.e., 183.3 cm3·mol–1.6 As shown in Table 6, G1,3 and G2,3 values are negative in all cases, which indicates the affinity of meloxicam by NMP and water. The meloxicam radius value (r3) was calculated as 0.417 nm. Preferential solvation parameters of meloxicam by NMP are also shown in Table 6. According to Figure 9, initially, the addition of NMP to neat water makes the δx1,3 values of meloxicam negative in the solvent systems from neat water to the mixture of x1 = 0.16. Maximum negative values of this parameter are obtained in the mixtures of x1 = 0.05 and 0.10, with δx1,3 = −3.21 × 10–2 and −3.19 × 10–2, respectively, which are higher in magnitude than |1.00 × 10–2|. Therefore, these results could be considered as a consequence of real preferential solvation effects by water on meloxicam rather than a consequence of the uncertainty propagation in IKBI calculations.92,93 The cosolvent action of NMP for increasing the meloxicam equilibrium solubility in these water-rich mixtures could be associated with the breaking of the ordered, “iceberg”-like structure of water around the nonpolar moieties of meloxicam, which, in turn, would increase the meloxicam equilibrium solubility and solvation.

Figure 9.

Preferential solvation parameters of meloxicam (3) in some {cosolvent (1) + water (2)} mixtures at T = 298.15 K. ●: N-methyl-pyrrolidone (1) + water (2); ○: dimethyl sulfoxide (1) + water (2);12 and ◊: N,N-dimethylformamide (1) + water (2).6

In {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures of composition 0.16 < x1 < 1.00, the δx1,3 values are positive, which indicates preferential solvation of meloxicam by NMP. The maximum δx1,3 value was observed in the mixture of x1 = 0.40 (δx1,3 = 5.41 × 10–2). This maximum positive δx1,3 value is also higher than |1.00 × 10–2|, being considered as a consequence of real preferential solvation effects by NMP on meloxicam.92,93 From a mechanistic point of view, in the mixture composition interval of 0.16 < x1 < 1.00, it is conjecturable that meloxicam could acts as a Lewis acid with the NMP molecules, owing to the unshared electron pairs of the carbonyl oxygen atom of this organic solvent. Thus, this cosolvent is more Lewis-basic than water, as remarkable by comparison of their Kamlet–Taft hydrogen bond-acceptor (HBA) parameters, namely, β = 0.77 for NMP and 0.47 for water.57 Additionally, Figure 9 allows the comparison of preferential solvation of meloxicam by NMP, DMSO,12 and DMF,6 in their respective aqueous mixtures. As observed, the cosolvent regions of preferential solvation are similar between DMSO and DMF, as well as the magnitudes of preferential solvation by both cosolvents. However, the composition interval of preferential hydration is lower with NMP regarding the other cosolvents, and the magnitude of preferential solvation by NMP is higher than those obtained with DMSO and DMF. Otherwise, the magnitude of maximal preferential hydration is similar in the cases of NMP and DMF. These behaviors could be a consequence of higher water-association effects like icebergs around the nonpolar groups of meloxicam, which, in turn, is also favored by the more hydrophobic moieties of the cosolvents as they exhibit less polar behaviors. In turn, the hydrophobic groups of the cosolvents could also act as water-association promotors, depending on their respective sizes.11 However, possible complexing effects of NMP with meloxicam should also be considered as well, in particular in compositions with a high proportion of water. Finally, based on all of the physicochemical analyses reported above, it is worth noting that this research expands the equilibrium solubility database about nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in aqueous–cosolvent mixtures.94

4. Conclusions

In this research, the mole fraction and molarity equilibrium solubility values of meloxicam in {NMP (1) + water (2)} mixtures at five temperatures from T = (293.15 to 313.15) K were determined, reported, and analyzed. Meloxicam mole fraction solubilities observed in these mixtures were adequately correlated with the Jouyban–Acree and Jouyban–Acree–van’t Hoff correlation models obtaining mean percentage deviations (MPDs) of 9.5–9.7%. Additionally, a number of predictive models involving Hansen or Abraham parameters, which were already trained using published data sets, and by employing the minimum number of measured experimental solubility data from this research produced MPDs of 57.5–71.4%. All apparent standard thermodynamic quantities relative to the dissolution and mixing processes of meloxicam were calculated, obtaining endothermal dissolution processes in all cases that were favored in NMP-rich mixtures. Nonlinear enthalpy–entropy compensation of transfer was observed, indicating different mechanisms for the cosolvent action on increasing meloxicam solubilization. IKBI calculations demonstrated preferential hydration of meloxicam in water-rich mixtures but preferential solvation by NMP in cosolvent mixtures of 0.16 < x1 < 1.00.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Departments of Pharmacy and Physics of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for facilitating the equipment and laboratories used. Financial support of Minciencias (formerly Colciencias) is also highly appreciated.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Budavari S.; O’Neil M. J.; Smith A.; Heckelman P. E.; Obenchain J. R. Jr; Gallipeau J. A. R.. et al. The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals, 13th ed.; Merck & Co., Inc.: Whitehouse Station (NJ), 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks P. M.; Day R. O.; et al. Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-differences and similarities. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 1716–1725. 10.1056/NEJM199106133242407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt G.; Homma D.; Schlegel K.; Utzmann R.; Schnitzler C. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic and related properties of meloxicam, a new non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent with favourable gastrointestinal tolerance. Inflamm. Res. 1995, 44, 423–433. 10.1007/BF01757699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Türck D.; Roth W.; Busch U. A review of the clinical pharmacokinetics of meloxicam. Rheumatology 1996, 35, 13–16. 10.1093/rheumatology/35.suppl_1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetman S. C.Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference, 36th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tinjacá D. A.; Martínez F.; Almanza O. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Solubility of meloxicam in aqueous binary mixtures of formamide, N-methylformamide and N,N-dimethylformamide: Determination, correlation, thermodynamics and preferential solvation.. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2021, 154, 106332 10.1016/j.jct.2020.106332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tinjacá D. A.; Martínez F.; Almanza O. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Dissolution thermodynamics and preferential solvation of meloxicam in (acetonitrile + water) mixtures. Phys. Chem. Liq. 2021, 59, 733–752. 10.1080/00319104.2020.1808658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tinjacá D. A.; Martínez F.; Almanza O. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Solubility, dissolution thermodynamics and preferential solvation of meloxicam in (methanol + water) mixtures. J. Solution Chem. 2021, 50, 667–689. 10.1007/s10953-021-01084-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tinjacá D. A.; Martínez F.; Almanza O. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Solubility of meloxicam in (Carbitol + water) mixtures: Determination, correlation, dissolution thermodynamics and preferential solvation. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 324, 114671 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golgoun S.; Mokhtarpour M.; Shekaari H. Solubility enhancement of betamethasone, meloxicam and piroxicam by use of choline-based deep eutectic solvents. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 27, 86–101. 10.34172/PS.2020.58. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tinjacá D. A.; Martínez F.; Almanza O. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Solubility, correlation, dissolution thermodynamics and preferential solvation of meloxicam in aqueous mixtures of 2-propanol. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 28, 130–144. 10.34172/PS.2021.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinjacá D. A.; Martínez F.; Almanza O. A.; Peña M. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Increasing the equilibrium solubility of meloxicam in aqueous media by using dimethyl sulfoxide as a cosolvent: Correlation, dissolution thermodynamics and preferential solvation. Liquids 2022, 2, 161–182. 10.3390/liquids2030011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R. C.; Sheskey P. J.; Quinn M. E.. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 6th ed.; American Pharmacists Association and Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone, PubChem. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (accessed Dec 7, 2020).

- N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone, ChemSpider. http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.12814.html (accessed Dec 7, 2020).

- Mokhatab S.; Poe W. A.; Mak J. Y.. Handbook of Natural Gas Transmission and Processing; Principles and Practices, 4th ed.; Elsevier, 2019; pp 231–269. [Google Scholar]

- Jouyban A.; Fakhree M. A. A.; Shayanfar A. Review of pharmaceutical applications of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 13, 524–535. 10.18433/J3P306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. J.; Langer R.; Shastri V. P. Role of N-methyl pyrrolidone in the enhancement of aqueous phase transdermal transport. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 912–917. 10.1002/jps.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H.-C.; Thoma D. S.; Yoon S.-R.; Cha J.-K.; Lee J.-S.; Jung U.-W. Bone regeneration using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone as an enhancer for recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in a rabbit sinus augmentation model. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4153073 10.1155/2017/4153073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald D. D.; Dunay D.; Hanlon G.; Hyne J. B. Properties of the N-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone-water system.. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1971, 49, 420–423. 10.1002/cjce.5450490321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Åkesson B.N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone, Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 35; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Henni A.; Hromek J. J.; Tontiwachwuthikul P. Amit Chakma, A. Volumetric properties and viscosities for aqueous N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone solutions from 25 ° C to 70 °C. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2004, 49, 231–234. 10.1021/je034073k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaichikov A. M. Thermodynamic characteristics of water–N-methylpyrrolidone mixtures and intermolecular interactions in them. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2006, 76, 626–633. 10.1134/S1070363206040219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dávila M. J.; Alcalde R.; Aparicio S. Pyrrolidone derivatives in water solution: An experimental and theoretical perspective. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 1036–1050. 10.1021/ie800911n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Abuín A.; Gómez-Díaz D.; La Rubia M. D.; Navaza J. M. Density, speed of sound, viscosity, refractive index, and excess volume of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + ethanol (or water or ethanolamine) from T = (293.15 to 323.15) K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2011, 56, 646–651. 10.1021/je100967k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimpour E.; Barzegar-Jalali M.; Shayanfar A.; Jouyban A. Generally trained models to predict drug solubility in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone+water mixtures at various temperatures. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 254, 34–38. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Cheng Y.-w.; Wang L.-j.; Li X. Solubility of terephthalic acid in aqueous N-methyl pyrrolidone and N,N-dimethyl acetamide solvents at (303.2 to 363.2) K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2008, 53, 1421–1423. 10.1021/je700635r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi R.Drug Solubilization using N-Methyl Pyrrolidone: Efficiency and Mechanism. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arizona, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi R.; Narazaki R.; Machatha S. G.; Yalkowsky S. H. Solubility improvement of drugs using N-methyl pyrrolidone. AAPS PharmSciTech 2008, 9, 366–376. 10.1208/s12249-008-9050-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayanfar A.; Acree W. E. Jr; Jouyban A. Solubility of clonazepam, diazepam, lamotrigine, and phenobarbital in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + water mixtures at 298.2 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2009, 54, 2964–2966. 10.1021/je9000153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khajir S.; Shayanfar A.; Acree W. E. Jr; Jouyban A. Effects of N-methylpyrrolidone and temperature on phenytoin solubility. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 285, 58–61. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.04.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soltanpour S.; Jouyban A. Solubility of acetaminophen and ibuprofen in polyethylene glycol 600, N-methyl pyrrolidone and water mixtures. J. Solution Chem. 2011, 40, 2032–2045. 10.1007/s10953-011-9767-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eghrary S. H.; Zarghami R.; Martinez F.; Jouyban A. Solubility of 2-butyl-3-benzofuranyl 4-(2-(Diethylamino)ethoxy)-3,5-diiodophenyl ketone hydrochloride (Amiodarone HCl) in ethanol + water and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + water mixtures at various temperatures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2012, 57, 1544–1550. 10.1021/je201268b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nozohouri S.; Shayanfar A.; Cárdenas Z. J.; Martinez F.; Jouyban A. Solubility of celecoxib in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + water mixtures at various temperatures: Experimental data and thermodynamic analysis. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 1435–1443. 10.1007/s11814-017-0028-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Chen G.; Cong Y.; Xu A.; Farajtabar A.; Zhao H. Equilibrium solubility, dissolution thermodynamics and preferential solvation of 6-methyl-2-thiouracil in aqueous co-solvent mixtures of methanol, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, N,N-dimethyl formamide and dimethylsulfoxide. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2018, 121, 55–64. 10.1016/j.jct.2018.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatefi A.; Rahimpour E.; Ghafourian T.; Martinez F.; Barzegar-Jalali M.; Jouyban A. Solubility of ketoconazole in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + water mixtures at T=(293.2 to 313.2) K. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 281, 150–155. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.02.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Liu Y.; Zheng M.; Zhang N.; Farajtabar A.; Zhao H. Solubility modelling, solvent effect and preferential solvation of allopurinol in aqueous co- solvent mixtures of ethanol, isopropanol, N,N-dimethylformamide and 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidone. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2019, 131, 478–488. 10.1016/j.jct.2018.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Farajtabar A.; Wang N.; Liu Z.; Fei Z.; Zhao H. Solubility of chloroxine in aqueous co-solvent mixtures of N,N-dimethylformamide, dimethyl sulfoxide, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone and 1,4-dioxane: Determination, solvent effect and preferential solvation analysis. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2019, 138, 288–296. 10.1016/j.jct.2019.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Farajtabar A.; Xing R.; Zhu Y.; Zhao H. Solubility of d-histidine in aqueous cosolvent mixtures of N,N-dimethylformamide, ethanol, dimethyl sulfoxide, and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone: determination, preferential solvation, and solvent effect. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2020, 65, 1695–1704. 10.1021/acs.jced.9b01051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jouyban K.; Agha E. M. H.; Hemmati S.; Martinez F.; Kuentz M.; Jouyban A. Solubility of 5-aminosalicylic acid in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + water mixtures at various temperatures. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 310, 113143 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-K.; Sim W.-Y.; Ha E.-S.; Park H.; Kim J.-S.; Jeong J.-S.; Kim M.-S. Solubility of bisacodyl in fourteen mono solvents and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + water mixed solvents at different temperatures, and its application for nanosuspension formation using liquid antisolvent precipitation. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 310, 113264 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Farajtabar A.; Xing R.; Zhu Y.; Zhao H. Equilibrium solubility determination, solvent effect and preferential solvation of amoxicillin in aqueous co-solvent mixtures of N,N-dimethylformamide, isopropanol, N-methyl pyrrolidone and ethylene glycol. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2020, 142, 106010 10.1016/j.jct.2019.106010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y.; Farajtabar A.; Zheng M.; Zhao H. Equilibrium solubility, solvent effect and preferential solvation of 5-nitrofurazone (form γ) in aqueous co-solvent mixtures of isopropanol, N-methyl pyrrolidone, ethanol and dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2020, 142, 106016 10.1016/j.jct.2019.106016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C.; Xu R.; Zhou Y.; Zhao H. Biapenem in binary aqueous mixtures of N,N-dimethylformamide, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, isopropanol and ethanol: Solute-solvent and solvent-solvent interactions, solubility determination and preferential solvation. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2020, 149, 106190 10.1016/j.jct.2020.106190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Farajtabar A.; Han G.; Zhao H. Phenformin in aqueous co-solvent mixtures of N,N-dimethylformamide, ethanol, N-methylpyrrolidone and dimethyl sulfoxide: Solubility, solvent effect and preferential solvation. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2020, 144, 106085 10.1016/j.jct.2020.106085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Farajtabar A.; Han G.; Zhao H. Griseofulvin dissolved in binary aqueous co-solvent mixtures of N,N-dimethylformamide, methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile and N-methylpyrrolidone: Solubility determination and thermodynamic studies. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2020, 151, 106250 10.1016/j.jct.2020.106250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio I. P.; Martínez F.; Peña M. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Solubility, dissolution thermodynamics and preferential solvation of sulfadiazine in (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone + water) mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 330, 115693 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino J. T.Cosolvents and Cosolvency. In Encyclopedia of Pharmaceutical Technology, Swarbrick J.; Boylan J. C., Eds.; Marcel Dekker, Inc: New York (NY), 1988; Vol. 3, pp 375–398. [Google Scholar]

- Martin A.; Bustamante P.; Chun A. H. C.. Physical Pharmacy: Physical Chemical Principles in the Pharmaceutical Sciences, 4th ed.; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia (PA), 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yalkowsky S. H.Solubility and Solubilization in Aqueous Media; American Chemical Society and Oxford University Press: New York (NY), 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jouyban A.Handbook of Solubility Data for Pharmaceutical; CRC Press: Boca Raton (FL), 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado D. R.; Holguin A. R.; Almanza O. A.; Martinez F.; Marcus Y. Solubility and preferential solvation of meloxicam in ethanol + water mixtures. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2011, 305, 88–95. 10.1016/j.fluid.2011.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holguín A. R.; Delgado D. R.; Martínez F.; Marcus Y. Solution thermodynamics and preferential solvation of meloxicam in propylene glycol + water mixtures. J. Solution Chem. 2011, 40, 1987–1999. 10.1007/s10953-011-9769-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi T.; Connors K. A. Phase solubility techniques. Adv. Anal. Chem. Instrum. 1965, 4, 117–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kratky O.; Leopold H.; Stabinger H.. DMA45 Calculating Digital Density Meter, Instruction Manual; Anton Paar, K.G.: Graz, Austria, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Barton A. F. M.Handbook of Solubility Parameters and Other Cohesion Parameters, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton (FL), 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y.The Properties of Solvents; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester (UK), 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Connors K. A.Thermodynamics of Pharmaceutical Systems: An Introduction for Students of Pharmacy; Wiley–Interscience: Hoboken (NJ), 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fedors R. F. A method for estimating both the solubility parameters and molar volumes of liquids. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1974, 14, 147–154. 10.1002/pen.760140211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacon Freitas J. T.; Santos-Viana O. M. M.; Bonfilio R.; Doriguetto A. C.; Benjamim de Araújo M. Analysis of polymorphic contamination in meloxicam raw materials and its effects on the physicochemical quality of drug product. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 109, 347–358. 10.1016/j.ejps.2017.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R.; Sarkar M. Spectroscopic studies of microenvironment dictated structural forms of piroxicam and meloxicam. J. Lumin. 2002, 99, 255–263. 10.1016/S0022-2313(02)00344-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luger P.; Daneck K.; Engel W.; Trummlitz G.; Wagner K. Structure and physicochemical properties of meloxicam, a new NSAID. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1996, 4, 175–187. 10.1016/0928-0987(95)00046-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. Q.; Tang P. X.; Li S. S.; Zhang L. L.; Li H. X-ray powder diffraction data for meloxicam, C14H13N3O4S2. Powder Diffr. 2014, 29, 196–198. 10.1017/S0885715614000153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noolkar S. B.; Jadhav N. R.; Bhende S. A.; Killedar S. G. Solid-state characterization and dissolution properties of meloxicam–moringa coagulant–PVP ternary solid dispersions. AAPS PharmSciTech 2013, 14, 569–577. 10.1208/s12249-013-9941-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirisolla J. Solubility enhancement of meloxicam by liquisolid technique and its characterization. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 835–840. 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alnaief M.; Obaidat R.; Mashaqbeh H. Loading and evaluation of meloxicam and atorvastatin in carrageenan microspherical aerogels particles. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 83–88. 10.7324/JAPS.2019.90112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas Z. J.; Jiménez D. M.; Delgado D. R.; Almanza O. A.; Jouyban A.; Martínez F.; Acree W. E. Jr. Solubility and preferential solvation of some n-alkyl-parabens in methanol + water mixtures at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2017, 108, 26–37. 10.1016/j.jct.2017.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kristl A.; Vesnaver G. Thermodynamic investigation of the effect of octanol–water mutual miscibility on the partitioning and solubility of some guanine derivatives. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1995, 91, 995–998. 10.1039/FT9959100995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Mathematical derivation of the Jouyban-Acree model to represent solute solubility data in mixed solvents at various temperatures. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 256, 541–547. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jouyban-Gharamaleki A.; Valaee L.; Barzegar-Jalali M.; Clark B. J.; Acree W. E. Jr. Comparison of various cosolvency models for calculating solute solubility in water-cosolvent mixtures. Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 177, 93–101. 10.1016/S0378-5173(98)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalkowsky S. H.; Roseman T. J.. Solubilization of drugs by cosolvents. In Techniques of Solubilization of Drugs; Yalkowsky S. H., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York (NY), 1981; pp 91–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jouyban A.; Romero S.; Chan H. K.; Clark B. J.; Bustamante P. A cosolvency model to predict solubility of drugs at several temperatures from a limited number of solubility measurements. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 594–599. 10.1248/cpb.50.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadmand S.; Kamari F.; Acree W. E. Jr; Jouyban A. Solubility prediction of drugs in binary solvent mixtures at various temperatures using a minimum number of experimental data points. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 10. 10.1208/s12249-018-1244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimpour E.; Jouyban A. Utilizing Abraham and Hansen solvation parameters for solubility prediction of meloxicam in cosolvency systems. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 328, 115400 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krug R. R.; Hunter W. G.; Grieger R. A. Enthalpy-entropy compensation. 1. Some fundamental statistical problems associated with the analysis of van’t Hoff and Arrhenius data. J. Phys. Chem. A 1976, 80, 2335–2341. 10.1021/j100562a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krug R. R.; Hunter W. G.; Grieger R. A. Enthalpy-entropy compensation. 2. Separation of the chemical from the statistical effect. J. Phys. Chem. B 1976, 80, 2341–2351. 10.1021/j100562a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruidiaz M. A.; Delgado D. R.; Martínez F.; Marcus Y. Solubility and preferential solvation of indomethacin in 1,4-dioxane + water solvent mixtures. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2010, 299, 259–265. 10.1016/j.fluid.2010.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bevington P. R.Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences; McGraw-Hill Book, Co.: New York (NY), 1969; pp 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen J. T.Modeling and Data Treatment in the Pharmaceutical Sciences; Technomic Publishing Co., Inc.: Lancaster (PA), 1996; pp 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Barrante J. R.Applied Mathematics for Physical Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River (NJ), 1998; p 227. [Google Scholar]

- Perlovich G. L.; Kurkov S. V.; Kinchin A. N.; Bauer-Brandl A. Thermodynamics of solutions III: Comparison of the solvation of (+)-naproxen with other NSAIDs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2004, 57, 411–420. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado D. R.; Almanza O. A.; Martínez F.; Peña M. A.; Jouyban A.; Acree W. E. Jr. Solution thermodynamics and preferential solvation of sulfamethazine in (methanol + water) mixtures. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2016, 97, 264–276. 10.1016/j.jct.2016.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero S.; Reillo A.; Escalera B.; Bustamante P. The behaviour of paracetamol in mixtures of aprotic and amphiprotic-aprotic solvents. Relationship of solubility curves to specific and nonspecific interactions. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 1061–1066. 10.1248/cpb.44.1061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson E. Enthalpy-entropy compensation analysis of pharmaceutical, biochemical and biological systems. Int. J. Pharm. 1983, 13, 115–144. 10.1016/0378-5173(83)90001-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler J. E.; Grunwald E.. Rates and Equilibria of Organic Reactions: As Treated by Statistical, Thermodynamic and Extrathermodynamic Methods; Dover Publications Inc.: New York (NY), 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante P.; Romero S.; Reillo A. Thermodynamics of paracetamol in amphiprotic and amphiprotic-aprotic solvent mixtures. Pharm. Pharmacol. Commun. 1995, 1, 505–507. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1995.tb00366.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante P.; Romero S.; Peña A.; Escalera B.; Reillo A. Nonlinear enthalpy-entropy compensation for the solubility of drugs in solvent mixtures: paracetamol, acetanilide and nalidixic acid in dioxane-water. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998, 87, 1590–1596. 10.1021/js980149x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez F.; Peña M. A.; Bustamante P. Thermodynamic analysis and enthalpy-entropy compensation for the solubility of indomethacin in aqueous and non-aqueous mixtures. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2011, 308, 98–106. 10.1016/j.fluid.2011.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y.Solvent Mixtures: Properties and Selective Solvation; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York (NY), USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y. On the preferential solvation of drugs and PAHs in binary solvent mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 2008, 140, 61–67. 10.1016/j.molliq.2008.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y. Preferential solvation of drugs in binary solvent mixtures. Pharm. Anal. Acta 2017, 8, 1000537. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Naim A. Preferential solvation in two- and in three-component systems. Pure Appl. Chem. 1990, 62, 25–34. 10.1351/pac199062010025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y. Solubility and solvation in mixed solvent systems. Pure Appl. Chem. 1990, 62, 2069–2076. 10.1351/pac199062112069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acree W. E. Jr. IUPAC-NIST Solubility Data Series. 102. Solubility of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in neat organic solvents and organic solvent mixtures. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2014, 43, 023102 10.1063/1.4869683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]