Abstract

Analysis of sequence variations among isolates of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. macacae from 14 Indian rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) at the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of the nuclear rRNA gene was undertaken. Like those from P. carinii f. sp. hominis, the ITS sequences from various P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates were not identical. Two major types of sequences were found. One type of sequence was shared by 13 isolates. These 13 sequences were homologous but not identical. Variations were found at 13 of the 180 positions in the ITS1 region and 28 of the 221 positions in the ITS2 region. These sequence variations were not random but exhibited definite patterns when the sequences were aligned. According to this sequence variation, ITS1 sequences were classified into three types and ITS2 sequences were classified into five types. The remaining specimen had ITS1 and ITS2 sequences substantially different from the others. Although some specimens had the same ITS1 or ITS2 sequence, all 14 samples exhibited a unique whole ITS sequence (ITS1 plus ITS2). The 5.8S rRNA gene sequences were also analyzed, and only two types of sequences that differ by only one base were found. Unlike P. carinii f. sp. hominis infections in humans, none of the monkey lung specimens examined in this study were found to be infected by more than one type of P. carinii f. sp. macacae. These results offer insights into the genetic differences between P. carinii organisms which infect distinct species.

Pneumocystis carinii is the major cause of pneumonia in AIDS patients and is one of the most common opportunistic pathogens in immunocompromised patients. P. carinii is also found in many different species of vertebrate animals. Although the morphologies of P. carinii from various animals are similar, nucleotide sequences of certain genes or genomic loci are variable. Examples of these genes include the major surface glycoproteins (22, 27, 28); beta-tubulin (4); alpha-tubulin (21); thymidylate synthase (18); arom (1); small (6) and large (19, 20, 25, 26) subunits of mitochondrial rRNAs; 5.8S (15), 26S (15), and 18S rRNAs (21); and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of nuclear rRNAs (16). Among these, nucleotide sequence variations in the large subunit mitochondrial rRNA gene and the ITS regions are the most profound. In addition, nucleotide sequences in these two regions are found to be unique to P. carinii from different species of animals. The ITS sequences of P. carinii from both rats and humans have been determined (16). The ITS sequences of human P. carinii (P. carinii f. sp. hominis) have been found to vary among different isolates, and this sequence variation has been used to type P. carinii f. sp. hominis isolates (2, 7–14, 16, 17, 19, 24). In this study, we sequenced the ITS regions of P. carinii from 14 Indian rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). It has been suggested that monkey P. carinii be named P. carinii f. sp. macacae (3). Like P. carinii f. sp. hominis, ITS sequence variations exist in different P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of specimen.

Fourteen lung tissues from 14 different SIV-infected Indian rhesus monkeys with P. carinii pneumonia (PCP) were obtained at necropsy. Diagnosis of PCP was based upon clinical signs including dyspnea, tachypnea, and development of interstitial pneumonia demonstrated by thoracic radiograph. All monkey lungs had moderate to severe interstitial infiltrates. P. carinii cysts were observed in methenamine-silver-nitrate-stained sections of all 14 lung tissue samples. These specimens were designated J637, C375, G762, G439, A349, G962, H468, J740, J308, H638, H423, I579, J129, and J203.

DNA isolation.

Approximately 50 mm3 of each monkey lung tissue was homogenized and placed into a 50-ml conical tube containing 10 ml of Marmur's solution (0.1 M NaCl, 0.04 M EDTA [pH 8.0]) and 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to lyse the cells. Proteinase K and RNase A were added to final concentrations of 100 μg/ml each to digest protein and RNA. After an overnight incubation at 37°C, a standard phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) extraction followed by a chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extraction was performed to purify the DNA. The DNA in the aqueous phase of the extraction was precipitated with ethanol. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in 250 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]).

PCR.

The purified DNA was used as a template to amplify the ITS regions by nested PCR using primers 1724F2 (5′-AGTTGATCAAATTTGGTCATTTAGAG-3′) and ITS2R (5′-CTCGGACGAGGATCCTCGCC-3′) for the first-step PCR and primers Fx (5′-TTCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCG-3′) and Rm (5′-TGATCCTGCCTGATTTGAGG-3′) for the second-step PCR as described previously (12, 14, 15). The PCR mixture contained 200 ng of template DNA, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 0.001% gelatin), 20 pmol of each PCR primer, a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 3 mM MgCl2, and 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase in a total volume of 40 μl. For PCR with primers 1724F2 and ITS2R, the initial stage was a 3-min denaturation at 94°C; the second stage was 5 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 62°C, and 1 min at 72°C; the third stage was 35 cycles of 40 s at 94°C, 40 s at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C; and the final stage was a 2-min extension at 72°C. When the Fx-Rx primer set was used, primer annealing was done at 59°C and the MgCl2 concentration was 2 mM in the PCR mix. All other PCR conditions were the same as described above. A positive specimen (bronchoalveolar lavage specimen obtained from a human patient with microscopically proven PCP) and a negative control sample containing no template DNA were included in each run. The amplified products were electrophoresed on a 1.2% agarose gel. The expected amplified fragments were approximately 620 bp.

Cloning and sequencing.

The PCR products were cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The recombinant plasmid DNA used for nucleotide sequencing was isolated using the Wizard Plus SV kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Nucleotide sequencing was performed with the dRhodamine Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.), and the sequences were determined by the ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin-Elmer).

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

DNA sequences were aligned using the program CLUSTAL W (23) and edited manually. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the maximum-likelihood analysis program DNAML of the PHYLIP software package (5) (version 3.57c; University of Washington, Seattle), and the phylogenetic trees were visualized using the Tree View program (Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Scotland).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been assigned accession numbers as follows: ITS1 type A, AF288827; ITS1 type A1, AF288828; ITS1 type A2, AF288829; ITS1 type A3, AF288830; ITS1 type B, AF288831; ITS1 type B1, AF288832; ITS1 type C, AF288833; ITS1 type D, AF288834; ITS2 type a, AF288835; ITS2 type al, AF288836; ITS2 type a2, AF288837; ITS2 type a3, AF288838; ITS2 type b, AF288839; ITS2 type b1, AF288840; ITS2 type c, AF288841; ITS2 type c1, AF288842; ITS2 type d, AF288843; ITS2 type d1, AF288844; ITS2 type e, AF288845; ITS2 type f, AF288846; 5.8S type I, AF288847; and 5.8S type II, AF288848.

RESULTS

With primer sets 1724F2-ITS2R and Fx-Rx, a fragment of approximately 620 bp was amplified from specimen J637. The PCR product was cloned and sequenced. Four recombinant clones of the PCR product were sequenced. The sequences obtained from all four clones were found to be identical. The sequence was then compared with that of P. carinii f. sp. hominis type Ee (Fig. 1). The type Ee sequence was chosen because it was used as a reference sequence previously (14). The first 31 bp of the sequence was found to be the same as those of the 3′ end of the 18S rRNA gene of P. carinii f. sp. hominis. Thirty-two of the last 33 bp (97% homology) of the sequence were identical to the first 33 bp of the 26S rRNA gene of P. carinii f. sp. hominis (Fig. 1). Among the 159 nucleotides of the 5.8S rRNA gene, only eight positions (95% homology) were different between P. carinii f. sp. hominis and P. carinii f. sp. macacae. These results indicate that this 620-bp fragment was indeed derived from P. carinii f. sp. macacae. Although the sequences of these three regions (18S, 5.8S, and 26S rRNA genes) were conserved among P. carinii f. sp. hominis and P. carinii f. sp. macacae, the ITS sequences were quite different. In the ITS1 region, only 104 of 180 nucleotides (58%) were identical to those of P. carinii f. sp. hominis. Similarly, only 111 of 221 (50%) nucleotides of the ITS2 region were found to be the same as those of P. carinii f. sp. hominis.

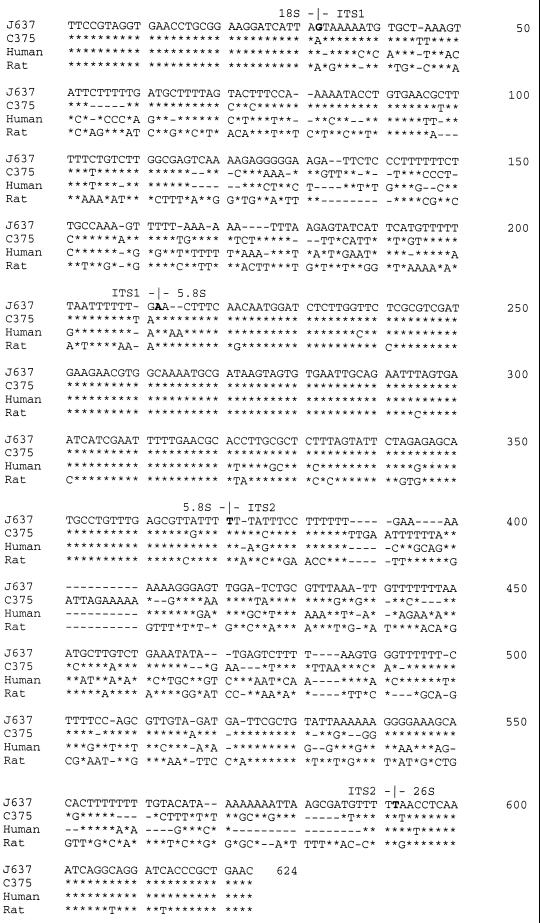

FIG. 1.

Alignment of ITS sequences of P. carinii f. sp. hominis, P. carinii f. sp. carinii, and P. carinii f. sp. macacae. The DNA sequences were aligned using the program CLUSTAL W and then edited manually. The sequence of specimen J637, which was the first P. carinii f. sp. macacae ITS sequence determined in this study, is used as the reference. C375 is another monkey lung specimen containing P. carinii with ITS sequences that are very different from those of the other 13 specimens examined in this study. Bases that are the same as those of J637 are represented by asterisks, missing bases are denoted by hyphens, and those that are different from the reference sequence are indicated. The P. carinii f. sp. hominis ITS sequence used in this study is that of type Ee (14), and that of the rat P. carinii (P. carinii f. sp. carinii) sequence is as described previously (16).

To determine whether the sequences of the ITS regions were variable among different P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates, 13 additional P. carinii-infected monkey lung specimens were examined. All 13 specimens generated the 620-bp PCR product. The PCR products were cloned and sequenced. Sequences of the extreme 3′ end of the 18S rRNA genes of all 14 specimens were found to be identical, and only one base, the second base, of the first 14 bases of the 26S rRNA gene was found to be variable among the 14 sequences. Only one position was found to be variable within the 158-bp 5.8S rRNA gene. When these 14 sequences were aligned, 13 of them were found to be similar to each other, and one (specimen C375) was quite different (Fig. 1). Bases of these 13 sequences that were found to be variable were aligned as shown in Fig. 2, and a consensus sequence based on the majority of the sequences at each variable position was developed (Fig. 2, top line).

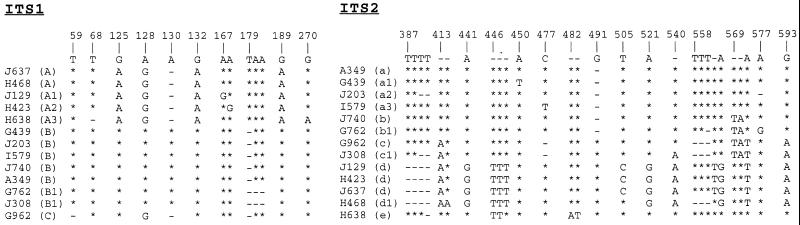

FIG. 2.

Variable bases of the 13 homologous ITS sequences of P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates. Locations of bases that exhibit sequence variation are shown above the sequence. The type of each sequence is indicated in the parentheses following the specimen identification number. The sequence shown at the top is the consensus sequence derived from the majority of the sequence at each position. Bases that are the same as the consensus sequence are represented by asterisks, missing bases are denoted by hyphens, and those that are different from the reference sequence are indicated.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have analyzed both ITS1 and ITS2 sequences of 14 P. carinii f. sp. macacae specimens. Similar to P. carinii f. sp. hominis, P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates also exhibit nucleotide sequence variations in ITS regions. Except for specimen C375 (Fig. 1), the sequence variations are not randomly distributed. They occur at certain positions. In the ITS1 region of the remaining 13 specimens, sequence variations are found at 13 of the 180 positions. Six (positions 125, 128, 130, 132, 179, and 189) of these 13 positions appear to be more critical. Based on sequence variations at these six positions, the ITS1 sequences can be classified into three major types, designated A, B, and C (Fig. 2). The ITS1 sequence of specimen C375 is designated type D.

For type A, the bases at these six positions are A, G, missing, A, T, and A (AG-ATA), respectively. For type B, these positions are G, A, A, G, missing, and G (GAAG-G), respectively. For type C, these positions are G, G, missing, G, missing, and G (GG-G-G), respectively. Five specimens (J129, H423, J637, H468, and H638) belong to type A, and seven specimens belong to type B. Only one specimen (G962) is considered to be type C. Minor sequence variations are also found at other positions. At position 167, the A residue is replaced by a G in specimen J129. The same change is found at position 168 in specimen H423. Since these two specimens differ from the typical A type by only one base, they are designated types A1 (J129) and A2 (H423), respectively. Specimen H638 differs from the typical type A sequence by two bases and is classified as type A3. It is missing a base at position 68 and has an A instead of a G at position 270. In the type B isolates, specimens G762 and J308 are missing the two A residues at positions 180 and 181; otherwise, they are identical to typical type B. These two specimens are designated type B1.

Classification of ITS2 sequences is much more complicated. Sequence variations occur at 28 positions, and only three specimens (J129, H423, and J637) have the same ITS2 sequence. The sequences of the remaining 10 specimens are classified into five types (designated a, b, c, d, and e). Types a, b, and c are distinguished according to sequence variations at positions 569 to 571. Type a is missing the first two bases in this region. The sequence for type b is TAA and that for type c is TAT at this region. The type d sequence is quite distinct from the other types. It has a G residue at positions 441, 521, and 562 and a run of 3 Ts at positions 446 to 448. Type e is closer to type a except that it has two extra Ts at positions 446 and 447 and AT residues at positions 482 and 483. The ITS2 sequence of specimen C375 is designated type f.

There are also minor variations among type a isolates. Specimen G439, designated a1, has a T instead of an A at position 450; otherwise, it is identical to a typical type a sequence. Specimen J203 is missing bases at positions 389, 390, and 577 and is designated type a2. Specimen I579 has a T instead of a C residue at position 477 and is designated type a3. Among the two type b isolates, specimen G762 is missing a T residue at position 560 and has a G instead of an a residue at position 577. Specimen J308 is designated c1 because it differs from the typical type c (specimen G962) at position 540, where specimen J308 has an extra A. Three specimens (J129, H423, and J637) have identical sequences and are designated type d. Specimen H468 is designated type d1 because it differs from type d at positions 505, where the C residue is replaced by a T, and at positions 558 to 560, where a run of three Ts is missing. It is also missing the T residue at position 561.

Since both the ITS1 and ITS2 sequences of specimen C375 are quite different from those of the other 13 specimens, we propose to classify P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates into two major groups. Group I consists of the 13 specimens that are further divided into various types based on the sequence types of ITS1 and ITS2 regions. Therefore, the 13 specimens can be designated as follows: J129, A1d; H423, A2d; J637, Ad; H468, Ad1; H638, A3e; A349, Ba; G439, Bal; J203, Ba2; I579, Ba3; J740, Bb; G762, B1b1; J308, B1c1; and G962, Cc. Specimen C375 belongs to group II and is designated type Df. According to this classification, every P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolate is distinct. No two isolates are found to be the same type in this study. This finding is very different from that of P. carinii f. sp. hominis isolates. In P. carinii f. sp. hominis isolates, the majority of the isolates found in various geographical locations belong to type Eg. Another difference between P. carinii f. sp. hominis and P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates is that coinfection by more than one type of P. carinii isolate is not found in the 14 monkey lung specimens we examined in this study.

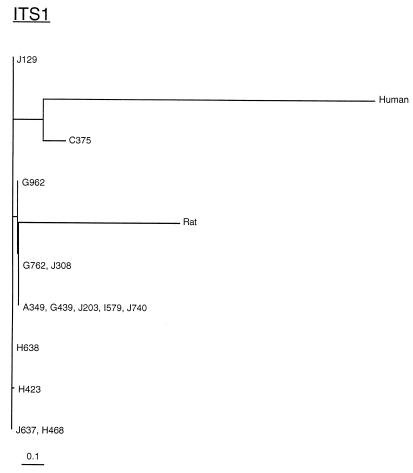

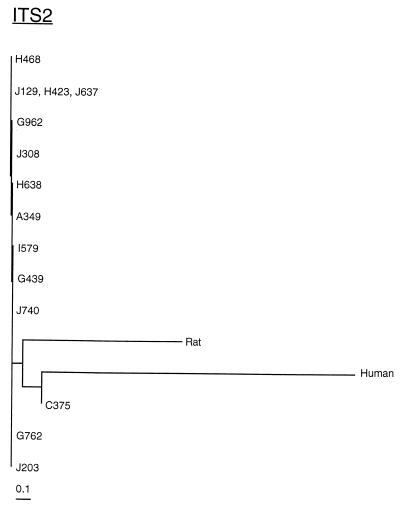

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the program DNAML in the PHYLIP software package (5). This program generates phylogenetic trees using the maximum-likelihood method. The results indicate that there are two major groups of P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates. One group is represented by specimen C375; the other group consists of the other 13 specimens. These results are consistent with those obtained by visual examination. The phylogenetic analyses also reveal that C375 is more closely related than the other 13 isolates to P. carinii f. sp. hominis (Fig. 3 and 4). Interestingly, these 13 isolates are closer to P. carinii f. sp. carinii (rat-derived P. carinii) than to P. carinii f. sp. hominis.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of ITS1 sequences from P. carinii f. sp. hominis, P. carinii f. sp. carinii, and all 14 P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates examined in this study. The phylogenetic tree was generated by the program DNAML of the PHYLIP software package, and the phylogram was drawn using the program TreeView. The lengths of the horizontal lines represent the degree of relatedness between various P. carinii isolates.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of ITS2 sequences from P. carinii f. sp. hominis, P. carinii f. sp. carinii, and all 14 P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates examined in this study. The phylogenetic tree was generated by the program DNAML of the PHYLIP software package, and the phylogram was drawn using the program TreeView. The lengths of the horizontal lines represent the degree of relatedness between various P. carinii isolates.

In summary, ITS sequences of 14 P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolates were examined. One isolate (C375) has very different ITS sequences. The other 13 isolates have similar sequences, with variations at certain nucleotide positions. These sequence variations exhibit certain patterns that allow classification of ITS1 into four types and classification of ITS2 sequences into six types. Some isolates have the same ITS1 or ITS2 sequences, but each isolate has a different combined ITS1 and ITS2 sequence. This observation suggests that each monkey was infected by a different strain of P. carinii f. sp. macacae. This is conceivable, since each monkey used in this study was caught in a different place. Whether P. carinii f. sp. macacae is transmissible among monkeys remains to be determined. The fact that each P. carinii f. sp. macacae isolate is different would make it feasible to develop a primate model to study P. carinii by transtracheal inoculation of P. carinii. It would be possible to distinguish the inoculated strain from the latent ones, if any, that become reactivated due to immunosuppression. At present, studies such as screening new drugs against P. carinii f. sp. hominis are mainly done using rodent models. The information derived from the rodent models may not be readily applicable to humans. A primate model would provide information more useful for the management of P. carinii infections in humans.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerji S, Lugli E B, Miller R F, Wakefield A E. Analysis of genetic diversity at the arom locus in isolates of Pneumocystis carinii. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1995;42:675–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett M S, Vermund S H, Jacobs R, Durant P J, Shaw M M, Smith J W, Tang X, Lu J J, Li B, Jin S, Lee C H. Detection of Pneumocystis carinii DNA in air samples: likely environmental risk to susceptible persons. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2511–2513. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2511-2513.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durand-Joly I, Wakefield A E, Palmer R J, Denis C M, Creusy C, Fleurisse L, Ricard I, Gut J P, Dei-Cas E. Ultrastructural and molecular characterization of Pneumocystis carinii isolated from a rhesus monkey. Med Mycol. 2000;38:61–72. doi: 10.1080/mmy.38.1.61.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edlind T D, Bartlett M S, Weinberg G A, Prah G N, Smith J W. The beta-tubulin gene from rat and human isolates of Pneumocystis carinii. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3365–3373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (phylogeny inference package), version 3.57c. Seattle: Department of Genetics. University of Washington; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter J A, Wakefield A E. Genetic divergence at the mitochondrial small subunit ribosomal RNA gene among isolates of Pneumocystis carinii from five mammalian host species. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:24S–25S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1996.tb04962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang B, Lu J J, Li B, Tang X, Bartlett M S, Smith J W, Lee C H. Development of type-specific PCR for typing Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis based on nucleotide sequence variations of the internal transcribed spacer regions of ribosomal RNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3245–3248. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3245-3248.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keely S P, Stringer J R. Sequences of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis strains associated with recurrent pneumonia vary at multiple loci. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2745–2747. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2745-2747.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latouche S, Roux P, Poirit J L, Lavrard I, Hermelin B, Bertrand V. Preliminary results of Pneumocystis carinii strain differentiation by using molecular biology. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:3052–3053. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.3052-3053.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latouche S, Ortona E, Masers E, Margutti P, Tamburrini E, Siracusano A, Guyot K, Nigou M, Roux P. Biodiversity of Pneumocystis carinii hominis: typing with different DNA regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:383–387. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.383-387.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latouche S, Poirot J L, Bernard C, Roux P. Study of internal transcribed spacer and mitochondrial large-subunit genes of Pneumocystis carinii hominis isolated by repeated bronchoalveolar lavage from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients during one or several episodes of pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1687–1690. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1687-1690.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee C H, Lu J J, Bartlett M S, Durkin M M, Liu T H, Wang J, Jiang B, Smith J W. Nucleotide sequence variation in Pneumocystis carinii strains that infect humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:754–757. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.754-757.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C H, Lu J J, Tang X, Jiang B, Li B, Jin S, Bartlett M S, Lundgren B, Atzori C, Orlando G, Cargnel A, Smith J W. Prevalence of various Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis types in different geographical locations. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:37S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1996.tb04973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C H, Helweg-Larsen J, Lundgren B, Lundgren J D, Tang X, Jin S, Li B, Bartlett M S, Lu J J, Olsson M, Luvas S B, Roux P, Cargnel A, Atzori C, Matos O, Smith J W. Update on Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis typing based on nucleotide sequence variations in the internal transcribed spacer regions of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:734–741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.734-741.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Rocourt M, Pan S, Liu C, Leibowitz M J. Sequence and variability of the 5.8S and 26S rRNA genes of Pneumocystis carinii. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3763–3772. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu J J, Bartlett M S, Shaw M M, Queener S F, Smith J W, Ortiz-Rivera M, Leibowitz M J, Lee C H. Typing of Pneumocystis carinii strains that infect humans based on nucleotide sequence variations of internal transcribed spacers of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2904–2912. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2904-2912.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu J J, Bartlett M S, Smith J W, Lee C H. Typing of Pneumocystis carinii strains with type-specific oligonucleotide probes derived from nucleotide sequences of internal transcribed spacers of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2973–2977. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2973-2977.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazars E, Odberg-Ferragut C, Dei-Cas E, Fourmaux M E, Aliouat E M, Brun-Pascaud M, Mougeot G, Camus D. Polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase gene of Pneumocystis carinii from different host species. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1995;42:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortona E, Margutti P, De Luca A, Tamburrini E, Visconti E, Siracusano A. Genetic variability in different Pneumocystis isolates from man and rats. New Microbiol. 1995;18:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinclair K, Wakefield A E, Banerji S, Hopkin J M. Pneumocystis carinii organisms derived from rat and human hosts are genetically distinct. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45:183–184. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stringer J R, Stringer S L, Zhang J, Baughman R, Smulian A G, Cushion M T. Molecular genetic distinction of Pneumocystis carinii from rats and humans. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:733–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stringer S L, Garbe T, Sunkin S M, Stringer J R. Genes encoding antigenic surface glycoproteins in Pneumocystis carinii from humans. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:821–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalities and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsolaki A G, Miller R F, Underwood A P, Banerji S, Wakefield A E. Genetic diversity at the internal transcribed spacer regions of the rRNA operon among isolates of Pneumocystis carinii from AIDS patients with recurrent pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:141–156. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakefield A E, Pixley F J, Banerji S, Sinclair K, Miller R F, Moxon E R, Hopkin J M. Amplification of mitochondrial ribosomal RNA sequences from Pneumocystis carinii DNA of rat and human origin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;43:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wakefield A E, Fritscher C C, Malin A S, Gwanzura L, Hughes W T, Miller R F. Genetic diversity in human-derived Pneumocystis carinii isolates from four geographical locations shown by analysis of mitochondrial rRNA gene sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2959–2961. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2959-2961.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright T W, Simpson-Haidaris P J, Gigliotti F, Harmsen A G, Haidaris C G. Conserved sequence homology of cysteine-rich regions in genes encoding glycoprotein A in Pneumocystis carinii derived from different host species. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1513–1519. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1513-1519.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright T W, Gigliotti F, Haidaris C G, Simpson-Haidaris P J. Cloning and characterization of a conserved region of human and rhesus macaque Pneumocystis carinii gpA. Gene. 1995;167:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00704-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]