Abstract

Assays measuring opsonophagocytic killing capacity of immune sera are good surrogate assays for assessing pneumococcal vaccine responses, but they are tedious to perform primarily because the enumeration of surviving bacteria requires the counting of individual bacterial colonies. To overcome this limitation, we have developed a simple and rapid chromogenic assay for estimating the number of surviving bacteria. In this method, the conventional opsonophagocytic killing assays were performed in microtiter wells with differentiated HL-60 cells as phagocytes. At the end of the assay the reaction mixture was cultured for an additional 4.5 h to increase the number of bacteria. After the short culture, XTT (3,3′-[1{(phenylamino)carbonyl}-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis[4-methoxy-6-nitro] benzene sulfonic acid hydrate) and coenzyme Q were added to the wells and the optical density at 450 nm was measured. Our study shows that changes in the optical density were proportional to the number of CFU of live bacteria in the wells. Also, the number of bacteria at the end of the 4.5-h culture was found to be proportional to the original number of bacteria in the wells. When the performance of the chromogenic assay was evaluated by measuring the opsonizing titers of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 6B and 19F, the sensitivity and precision of the new method were similar to those of the conventional opsonization assay employing the colony counting method. Furthermore, the results of this chromogenic assay obtained with 33 human sera correlate well with those obtained with the conventional colony counting method (R > 0.90) for the two serotypes (6B and 19F). Thus, this simple chromogenic assay would be useful in rapidly measuring the capacities of antisera to opsonize pneumococci.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important pathogen, and there is currently an effort to develop a vaccine against S. pneumoniae that would be more effective than the current 23-valent vaccine (14). Vaccine development would be facilitated if there were a simple surrogate assay for pneumococcal vaccine responses. Antibody concentrations estimated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-type methods are commonly used as the measure of vaccine responses. However, it was found that ELISAs for pneumococcal antibodies were sometimes nonspecific, thus often producing falsely high responses (4, 17). Even if the concentration of pneumococcal antibody could be accurately determined by ELISA, ELISA may measure nonfunctional low-avidity antibodies as well as high-avidity antibodies (3, 6). For these reasons, assays, such as the opsonophagocytic assay, that measure the function of pneumococcal antibodies would be useful.

While the opsonophagocytic killing assay is widely accepted as one of the best surrogate assays for vaccine-induced protection, the assay is tedious to perform, and several improvements have been made to simplify the assay. For instance, the classical assay was greatly simplified with the use of microtiter plates, frozen bacterial aliquots (1), and differentiated-HL-60 cells (13). We have recently developed a double-serotype opsonization assay which can yield the opsonophagocytic titers of two different serotypes in a single assay with the use of antibiotic-resistant pneumococci (12). While these modifications have reduced the amount of required effort and serum, the surviving bacteria still need to be enumerated by counting their colonies. Moreover, the assays need to be performed for many different serotypes because pneumococcal vaccines contain up to 23 serotypes. Consequently, the difficulties in counting colonies make the assay impractical for a large-scale use.

To eliminate the need to count bacterial colonies, we investigated the use of a formazan dye, XTT (3,3′-[1{(phenylamino)carbonyl}-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis[4-methoxy-6-nitro] benzene sulfonic acid hydrate) (15). XTT is converted to a colored, water-soluble product by live (but not dead) eukaryotic as well as prokaryotic cells (15). This property can be useful for assays measuring the ability of antisera to kill bacteria with or without neutrophils. However, the conversion of XTT by bacteria is relatively inefficient, and XTT can be used to measure the ability of neutrophils to kill various bacteria only when a large number of bacteria are present in the reaction well (15). Unfortunately, the standardized pneumococcal opsonization assay uses a small number (e.g., 1,000 CFU/well) of target bacteria. Therefore, XTT would not be useful unless the number of pneumococci surviving at the end of the assay could be increased in proportion to the number of surviving bacteria. We found that a brief (e.g., 4 to 5-h) culture prior to adding XTT increases the cell number and that the capacity of antisera to opsonize S. pneumoniae can be rapidly and easily determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples.

Adult volunteers were immunized with a 23-valent polysaccharide (PS) vaccine available from either Merck (West Point, Pa.) or Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines (Pearl River, N.Y.), and serum samples were obtained either before and/or 1 month after the vaccination. A human serum pool (HSP-3) was prepared by mixing equal volumes of sera from 1,638 blood donors (9). The pool was stored in aliquots at −20°C, and the pool was incubated in a 56°C water bath for 30 min before being added to Todd-Hewitt broth containing 0.5% yeast extract (THY medium). Another serum pool (Ppool10) was made by pooling equal volumes of the sera from 10 individuals who received a pneumococcal PS vaccine 1 month before phlebotomy. Ppool10 was used as a control for opsonophagocytic assays. Twenty-two postimmune serum samples were mixed with their own preimmune sera to obtain the samples with low opsonization titer and they were used to produce the data shown below (see Fig. 5).

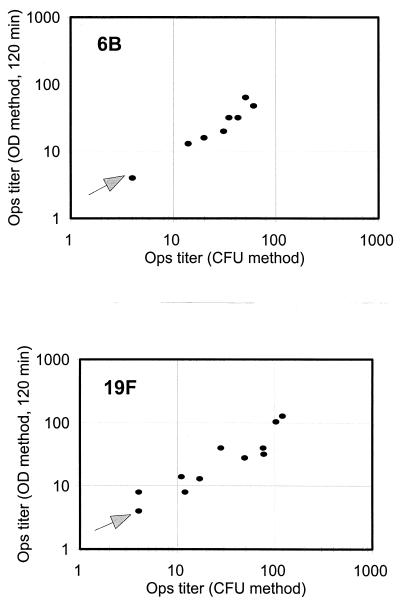

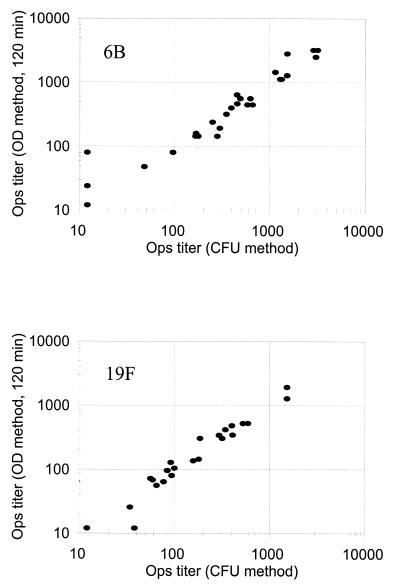

FIG. 5.

Comparison of the results obtained with the conventional method (x axis) and the chromogenic method (y axis) for serotype 6B (top panel) and serotype 19F (bottom panel). Fifteen serum samples for serotype 6B and 12 serum samples for serotype 19F had undetectable opsonization titers (i.e., <8) by both methods. One data point near the origin in each figure (marked with an arrow) represents these samples. Excluding these samples with undetectable titers, the data points have correlation coefficients of 0.93 for serotype 6B and 0.90 for serotype 19F. Ops, opsonization.

Bacteria.

Three strains of pneumococci (strains DS221494, DS2212, and DS2217) were obtained from G. Carlone at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Ga.). Their serotypes were, respectively, 14, 6B, and 19F. A streptomycin-resistant variant of DS2212 was obtained as described before (12) and labeled R6BSR. An optochin-resistant variant of DS2217 was similarly obtained and labeled R19FOR. R6BSR and R19FOR were grown in THY broth, aliquoted, and frozen at −70°C until used.

Double-serotype opsonophagocytic killing assay.

Double-serotype opsonization assays were performed as previously described (12). Briefly, differentiated HL-60 cells were diluted to 107 cells/ml in Hanks' buffer supplemented with 0.1% gelatin and 10% fetal calf serum (HGF buffer). The serum samples for the test were serially diluted in HGF buffer. To obtain the maximal assay sensitivity, undiluted serum was applied to the first well of the serial dilution. Each strain (R6BSR or R19FOR) of frozen bacteria was thawed and was diluted to 105 CFU/ml in HGF buffer. The two bacterial solutions were mixed (1:1 by volume), and 20 μl of the mixed bacterial solution was added to 10 μl of a diluted serum sample in a well of 96-well microtiter plate. After a 15-min incubation at 37°C, 40 μl of HL-60 cell suspension and 10 μl of baby rabbit complement (Pelfreeze, Browndeer, Wis.) were added to each well. The mixture was incubated for 45 min at 37°C with shaking. A 5 μl aliquot of reaction mixture was plated in a THY agar plate containing streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and another 5 μl was plated in a THY agar plate containing optochin (5 μg/ml). The THY agar plates were incubated in a candle jar at 37°C for 7 to 9 h, and bacterial colonies on the plates were counted. The opsonization titer of a serum is defined as the final dilution of a serum that results in half as many colonies as are seen with the control well containing all the reactants except for the serum. For instance, if 10 μl of the neat serum added to the well killed half of the bacteria, the opsonization titer is 8, because the serum was diluted with the reactants. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate.

Chromogenic opsonophagocytic killing assay.

Following the double-serotype opsonization assay and after replica plating in THY agar, the remaining reaction mixture was split into two by transferring about one-half (40 μl) to another microtiter plate. To the wells in the new plate, 20 μl of THY both containing 0.2% saponin, 10% HSP-3, and optochin (5 μg/ml) was added. The human serum was added to minimize the variable nutrient effect of the serum present in the test wells at various concentrations. Saponin was added to lyse HL-60 cells, which can degrade XTT. To the wells in the original plate, 20 μl of THY broth containing 0.2% saponin, 10% HSP-3, and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) was added. The presence of optochin or streptomycin permits selective growth of serotype 19F or 6B, respectively. After incubating the plates for 4.5 h at 37°C, 20 μl of a freshly made XTT substrate solution was added to each well. The substrate solution is phosphate-buffered saline containing XTT (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.) and coenzyme Q (40 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical). The plates were incubated at room temperature, and the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was measured with an ELISA reader (model EL309; BioTek Instrument, Winooski, Vt.) at 0, 30, and 120 min. “Delta ODs” were obtained by subtracting the OD obtained at 0 min from the OD obtained at either 30 or 120 min. The opsonization titer of a serum is defined as the final dilution of serum that produces delta OD that was obtained with 500 CFU/well, which is half of the initial number of bacteria of each serotype. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate.

RESULTS

Characterization of chromogen reaction step.

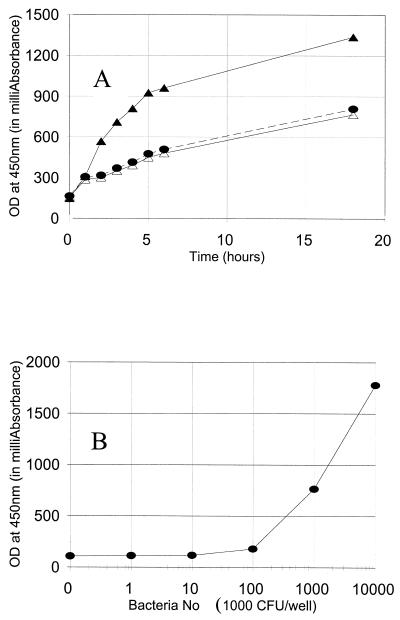

To determine the reaction time and to determine that only the living, but not dead, pneumococci convert XTT to water-soluble orange formazan, 100 μl of THY broth containing zero, 2 × 106 living, or 2 × 106 dead pneumococci (strain DS2212) was mixed with 50 μl of the XTT substrate solution in a microtiter well, and its OD450 was monitored during an incubation at room temperature. Dead pneumococci were prepared by incubating at 65°C for 1 h. Due to the absorption of the light by the culture medium, OD450 was readily detectable at the beginning of the reaction. The OD of the wells containing no bacteria or dead bacteria slowly increased over time, indicating that XTT spontaneously became colored product but the dead bacteria did not actively convert XTT to the colored product. However, the OD450 of the wells containing the live bacteria increased severalfold faster than those of the wells with no or dead bacteria for the first 5 h (Fig. 1A). This indicates clearly that the live bacteria produced the chromogenic product. After 5 h of incubation, the rate of OD change of the wells with the live bacteria became similar to those containing no bacteria. This may have happened because the bacteria died in 5 h. Based on these results, 1- to 3-h time periods were chosen to be the optimum for the chromogenic reaction.

FIG. 1.

(A) OD450 (y axis) versus time of color development (x axis). The wells assayed contained either 2 × 106 live cells of S. pneumoniae 6B serotype strain DS2212 (solid triangle), 2 × 106 heat-killed cells of S. pneumoniae 6B serotype strain DS2212 (open triangle), or no bacteria (solid circle). (B) OD450 (y axis) versus the number of live pneumococci in the well (x axis). S. pneumoniae serotype 14 (strain DS221494) was added to the well, and the OD was obtained after a 2-h incubation with XTT and was expressed in milliabsorbance units.

To establish the sensitivity of the chromogenic reaction, we determined the number of pneumococci necessary to produce detectable OD changes by adding various numbers of bacteria to each well and monitoring the OD450 after a 2-h incubation. As shown in Fig. 1B, the increase in OD450 was demonstrable when the wells contained 105 to 107 CFU of pneumococci. Also, within this range of bacterial density, the rate of OD change was proportional to the number of live bacteria in the well.

Characterization of culture condition.

Since 1,000 CFU of the target pneumococci are added to each well in a routine pneumococcal opsonization assay (13), the number of bacteria must be amplified by 102- to 103-fold, to 105 to 107 CFU/well, in proportion to the original number of live bacteria in the well. To achieve this, we investigated the culture conditions by testing various culture media and culture periods. Studies of various culture supplements added to the wells at the end of the opsonization assay verified that THY broth containing 10% human serum and 0.2% saponin was satisfactory. THY medium was chosen as the basic supplement because it supported the growth of S. pneumoniae well and had an OD450 low enough to pose no practical problems. HSP-3 (10%) was added to the medium because some human serum enhances the growth of bacteria. Addition of catalase did not change the performance of the medium (data not shown) and was not added to the medium. HL-60 cells, which can convert XTT to the colored product, were lysed by adding saponin (0.2%) to the culture medium. Saponin, up to 0.1%, had little effect on the growth of pneumococci (data not shown), and the added (0.2%) saponin would be diluted threefold during the assay.

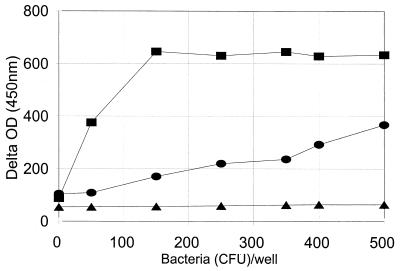

After too long a period of culture, the bacterial density would be independent of the initial density of bacteria. Thus, we needed to determine the optimum culture period, i.e., one short enough to reflect the initial number of bacteria but long enough to produce a sufficient number of bacteria. To identify the optimum period, we inoculated each well with 40 μl containing a variable (0 to 1,000 CFU) number of pneumococci, added 20 μl of the culture supplement, and incubated the wells at 37°C for 3, 4.5, and 6 h. After the incubation, 20 μl of XTT substrate solution was added and OD450 was monitored at 0 and 2 h. To compensate for the light absorption by the medium, the temporal change in OD (delta OD), obtained by subtracting the initial OD from the final OD, was used to estimate the number of bacteria. As shown in Fig. 2 a 3-h culture was too short, and no signal could be detected even for the wells seeded with 1,000 CFU of pneumococci. On the other hand, a 6-h incubation was too long and the OD changes were the same as long as the wells were seeded with more than 150 CFU (Fig. 2). Incubation for 4.5 h was found to be the best. The OD450 changes were readily detectable and remained proportional to the number of bacteria used to seed the wells. Assuming that bacteria divide every 30 min, the number of bacteria should have increased by 29 (512)-fold in 4.5 h and 1,000 CFU would have increased to 5 × 105 CFU. Thus, this incubation period is consistent with our previous conclusion in Fig. 1B. For all subsequent experiments, the bacteria were cultured for 4.5 h after the culture supplement was added to each well.

FIG. 2.

Delta OD (y axis) versus the number of bacteria added to the wells at the beginning of culture (x axis). After the bacteria were added to the well, the culture supplement was added and the well was incubated at 37°C for 3 h (triangle), 4.5 h (circle), or 6 h (square). The culture supplement contained THY broth, 0.2% saponin, and 10% HSP-3. The delta OD was expressed in milliabsorbance units and was obtained by subtracting the OD450 at the beginning of the color development period from the OD450 obtained at the end of the color development.

Comparison of chromogenic opsonization assay with a conventional assay.

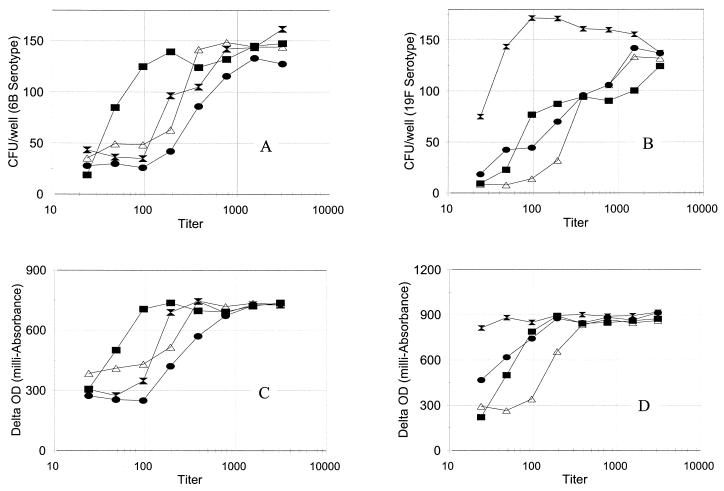

Once the conditions for the bacterial culture and the chromogenic reaction were determined, we compared the sensitivities of the chromogenic and the conventional (i.e., colony counting) opsonization assays by performing both assays for 6B and 19F serotypes with four serum samples. The curves describing delta OD versus serum dilution and the number of CFU of bacteria versus serum dilution had almost identical shapes for both 6B and 19F serotypes (Fig. 3), and the nearly identical shapes suggested that the assay sensitivity would be identical. Both assays produced comparable titers for the four samples. Delta OD is therefore a good indication of the number of bacteria, and the chromogenic assay appears to perform as anticipated.

FIG. 3.

CFU of bacteria versus dilution of serum samples (A and B) or delta OD versus dilution of serum samples (C and D) for serotype 6B (A and C) and serotype 19F (B and D). One sample is a serum pool, Ppool10 (solid square), and the others are serum samples from three persons who received a pneumococcal PS vaccine 1 month prior to phlebotomy. Delta OD was expressed in milliabsorbance units and was obtained by subtracting the OD450 obtained at the beginning of the color development from the OD450 after 2 h of color development.

Assay precision was determined by analyzing one serum pool (Ppool 10) five different times in both ways for 6B and 19F serotypes (Table 1). While the coefficient of variation for 6B serotype was higher than that for 19F serotype, the two methods produced comparable coefficients of variation for both serotypes. Thus, the serotype-dependent variability in the precision is not due to the method, and both methods provide comparable assay precision.

TABLE 1.

Precision of two opsonophagocytic killing assaya

| Serotype and assay | Geometric mean titer | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| 6B | ||

| Chromogenic | 468 | 281–776 |

| Conventional | 590 | 312–1,120 |

| 19F | ||

| Chromogenic | 728 | 583–908 |

| Conventional | 644 | 498–831 |

Each assay was performed five times.

We then examined whether both opsonization assays produce comparable results by testing 33 human serum samples by both assays for 6B and 19F serotypes. The samples with undetectable titer were declared to have titer of 12, or half of the minimum detectable titer. The minimum detectable titer was 24 because all the serum samples were diluted threefold and all the samples became diluted eightfold during the opsonization assay with various reactants. The results of both assays correlated well for both serotypes (Fig. 4) as shown by the very high r values (>0.95). One outlier data point was noted for serotype 6B. The outlier sample had an undetectable opsonization titer by the conventional assay but had a clearly demonstrable opsonization titer by the chromogenic assay. When the curve for OD versus serum dilution was examined, one data point in the middle of the titration had one abnormally small OD change, and this low OD point yielded a detectable opsonization titer. Without this low data point, the sample would have been declared to have an undetectable opsonization titer, and it is likely that there was a technical problem in assaying this sample.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the results obtained with the conventional method (x axis) and the chromogenic method (y axis) for serotype 6B (top panel) and serotype 19F (bottom panel). The correlation coefficients were 0.96 for serotype 6B and 0.99 for serotype 19F. Seven serum samples for serotype 6B and 10 serum samples for serotype 19F had undetectable opsonization titers (i.e., <24) by both methods. One data point near the origin in each figure represents these samples. Ops, opsonization.

Most samples tested as described above had relatively high (i.e., >100) titers. To evaluate the new method for the samples with low titers, we diluted 22 postimmune samples with their preimmune sera and tested them against 6B and 19F serotypes for opsonization titers. Because the samples have low titers, undiluted samples were used here as the first sample in the serial dilution and the samples with undetectable titers were declared to have titer of 4, or half of the minimum detectable titer. As shown in Fig. 5, the two methods were highly correlated (r = 0.93 for 6B; r = 0.90 for 19F). Thus, the new method correlates well with the conventional method for the samples with low opsonization titers.

When the data obtained with 30 min of color development were examined, the signal-to-noise ratio was slightly less than the ratio with the 2-h color development period, but the results were similar to those obtained with 2 h of color development (data not shown). Thus, any color development time between 0.5 and 2 h should provide the same results.

DISCUSSION

Chromogenic substrates have often been used to detect the number of viable cells. They have been used to measure proliferation of lymphocytes (11), and to enumerate fungal cells (5), as well as Mycobacterium bovis (7). It was also used by Stevens and Olsen (15) to determine the capacity of immune sera to opsonize bacteria. They were able to use XTT without introducing a short culture step because their opsonization assay used a very large number of bacteria. Since the current opsonization assay for pneumococcal antibodies uses very few target bacteria (13), we introduced a short culture step, during which the number of bacteria was increased about 1,000-fold. We now report that this short culture is practical and the chromogenic opsonization assay yields results that are comparable to the assay based on the counting of bacterial colonies.

Because the dyes measuring the number of viable cells can be useful for many different purposes, many different tetrazolium compounds have been produced. Among them, MTT, which is chemically stable, is commonly used, but MTT produces nonsoluble products, and its use requires a step to dissolve the product. This additional step would have increased the complexity of the assay. We therefore chose to use XTT, which gave us a simpler assay because it produces water-soluble products that absorb light at 450 nm (15). The substrate solution did have to be freshly prepared before each reaction, because XTT is unstable in solution. An interesting choice of dye would have been 5-cyano-2,3 ditolyl tetrazolium chloride (8). This compound produces a fluorescent product, which might make the assay more sensitive. Increased sensitivity may eliminate the need to increase the number of bacteria by culturing, and therefore the assay could be made even simpler with this dye. Unfortunately, we could not evaluate this dye, because the detection of the fluorescence would require a new piece of equipment.

Compared to other assays for measuring opsonic capacity of pneumococcal antibodies, this chromogenic assay is much easier and simpler to perform. For instance, the conventional opsonization assay requires a time-consuming step of colony counting. Another opsonization assay method uses a radiolabel (16), which is inconvenient and increasingly more difficult to use because of regulatory burden. Recently, a new method of measuring the opsonophagocytic capacity of sera was developed in which phagocytosis of fluorescent bacteria by phagocytes was measured (2, 10). This method, however, requires a flow cytometer, an expensive piece of specialized equipment, so that only certain laboratories can use this method. In addition, this method measures not the opsonophagocytic killing but the opsonophagocytosis. Compared to these alternative opsonization assays, the present chromogenic assay is simple and requires only commonly available instruments.

In terms of the ease of the assay, this chromogenic assay compares favorably even to ELISA. Clearly, this opsonization assay still needs cell culture facilities to culture the HL-60 cells. However, except for this, the chromogenic method only uses equipment already used for ELISA. Furthermore, the chromogenic assay results could be analyzed with the computer programs used to analyze ELISA data so that only minimal additional effort would be needed to set up this opsonization assay in a laboratory which already performs ELISAs. We therefore conclude that by using the double-serotype opsonization assay, the chromogenic opsonization assay may require less effort to perform than the ELISA.

In view of these advantages offered by the chromogenic opsonization assay, the assay could have a very wide appeal as the primary measure of pneumococcal vaccine response. Therefore, we believe that our study described here should be independently confirmed and validated by other laboratories for additional serotypes included in the pneumococcal vaccine. Also, both the short culture and the chromogen can be used to develop a very simple assay for measuring the bactericidal capacities of sera. If this chromogenic opsonization assay is found to be useful for determining pneumococcal vaccine responses, the direct measurement of the opsonophagocytic capacity or the bactericidal activity may become popular as the primary measure of the immune responses to various vaccines in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. Frasch and M. Loeb for their critical reading of the manuscript and E. Henderson for her secretarial help.

This work was supported with a fund from the National Institutes of Health (AI-85334). M. H. Nahm is partially supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases contract NO1 AI-45248.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaberge I S, Hvalbye B, Lovik M. Enhancement of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6B infection in mice after passive immunization with human serum. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:125–137. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso DeVelasco E, Dekker H A T, Antal P, Jalink K P, van Strijp J A G, Verheul A F M, Verhoef J, Snippe H. Adjuvant Quil A improves protection in mice and enhances opsonic capacity of antisera induced by pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccines. Vaccine. 1994;12:1419–1422. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anttila M, Eskola J, Ahman H, Kayhty H. Avidity of IgG for Streptococcus pneumoniae type 6B and 23F polysaccharides in infants primed with pneumococcal conjugates and boosted with polysaccharide or conjugate vaccines. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1614–1621. doi: 10.1086/515298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coughlin R T, White A C, Anderson C A, Carlone G M, Klein D L, Treanor J. Characterization of pneumococcal specific antibodies in healthy unvaccinated adults. Vaccine. 1998;16:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freimoser F L, Jakob C A, Aebi M, Tuor U. The MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-y)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay is a fast and reliable method for colorimetric determination of fungal cell densities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3727–3729. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3727-3729.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldblatt D, Vaz A R, Miller E. Antibody avidity as a surrogate marker of successful priming by Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines following infant immunization. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1112–1115. doi: 10.1086/517407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kairo S K, Bedwell J, Tyler P C, Carter A, Corbel M J. Development of a tetrazolium salt assay for rapid determination of viability of BCG vaccines. Vaccine. 1999;17:2423–2428. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai M, Yamaguchi N, Nasu M. Rapid enumeration of physiologically active bacteria in purified water used in the pharmaceutical manufacturing process. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:496–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madassery J V, Kwon O H, Lee S Y, Nahm M H. IgG2 subclass deficiency: IgG subclass assays and IgG2 concentrations among 8015 blood donors. Clin Chem. 1988;34:1407–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez J E, Romero-Steiner S, Pilishvili T, Barnard S, Schinsky J, Goldblatt D. A flow cytometric opsonophagocytic assay for measurement of functional antibodies elicited after vaccination with the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:581–586. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.581-586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mossman T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nahm M H, Briles D E, Yu X. Development of a multi-specificity opsonophagocytic killing assay. Vaccine. 2000;18:2768–2771. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero-Steiner S, Libutti D, Pais L B, Dykes J, Anderson P, Whitin J C, Keyserling H L, Carlone G M. Standardization of an opsonophagocytic assay for the measurement of functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae using differentiated HL-60 cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:415–422. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.4.415-422.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siber G R. Pneumococcal disease: prospects for a new generation of vaccines. Science. 1994;265:1385–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.8073278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens M G, Olsen S C. Comparative analysis of using MTT and XTT in colorimetric assay for quantative bovine neutrophil and bactericidal activity. J Immunol Methods. 1993;157:225–231. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90091-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitharsson G, Jonsdottir I, Jonsson S, Valdimarsson H. Opsonization and antibodies to capsular and cell wall polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:592–599. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu X, Sun Y, Frasch C E, Concepcion N, Nahm M H. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide preparations may contain non-C-polysaccharide contaminants that are immunogenic. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:519–524. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.519-524.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]