Abstract

Study Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to determine the impact age has on LOS and discharge disposition following elective ACDF for cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM).

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was performed using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2016 and 2017. All adult patients >50 years old undergoing ACDF for CSM were identified using the ICD-10-CM diagnosis and procedural coding system. Patients were then stratified by age: 50 to 64 years-old, 65 to 79 years-old, and greater than or equal to 80 years-old. Weighted patient demographics, comorbidities, perioperative complications, LOS, discharge disposition, and total cost of admission were assessed.

Results:

A total of 14 865 patients were identified. Compared to the 50-64 and 65-79 year-old cohorts, the 80+ years cohort had a significantly higher rate of postoperative complication (50-64 yo:10.2% vs. 65-79 yo:12.6% vs. 80+ yo:18.9%, P = 0.048). The 80+ years cohort experienced significantly longer hospital stays (50-64 yo: 2.0 ± 2.4 days vs. 65-79 yo: 2.2 ± 2.8 days vs. 80+ yo: 2.3 ± 2.1 days, P = 0.028), higher proportion of patients with extended LOS (50-64 yo:18.3% vs. 65-79 yo:21.9% vs. 80+ yo:28.4%, P = 0.009), and increased rates of non-routine discharges (50-64 yo:15.1% vs. 65-79 yo:23.0% vs. 80+ yo:35.8%, P < 0.001). On multivariate analysis, age 80+ years was found to be a significant independent predictor of extended LOS [OR:1.97, 95% CI:(1.10,3.55), P = 0.023] and non-routine discharge [OR:2.46, 95% CI:(1.44,4.21), P = 0.001].

Conclusions:

Our study demonstrates that octogenarian age status is a significant independent risk factor for extended LOS and non-routine discharge after elective ACDF for CSM.

Keywords: octogenarian, extended LOS, non-routine discharge, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, cervical spondylotic myelopathy

Introduction

Recently, healthcare expenditures in the United States have been rising at an unprecedented rate, resulting in efforts by hospitals and policymakers to mitigate costs and improve quality of care.1-4 In spinal surgery, extended hospital length-of-stay (LOS) and non-routine discharge disposition have emerged as quality metrics associated with greater healthcare costs,5-7 perioperative complications,6,7 patient dissatisfaction, 8 and mortality.6,7 One common spinal surgery procedure, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), has surfaced as a popular treatment for cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM), with the number of operations performed nation-wide nearly doubling from 2003 to 2013. 9 Therefore, there is a need for further identification of patient risk factors predictive of extended LOS and non-routine discharge after ACDF for CSM.

Due to the rising life-expectancy in the United States, octogenarians (those aged between 80 and 89 years) are becoming an increasingly common patient population undergoing degenerative spinal fusion operations.10-12 Given that greater than 80% of octogenarians have multiple preexisting morbidities and weakened physiological systems, octogenarians represent a uniquely challenging patient population in spinal surgery. 13 Nonetheless, the impact of this impaired health status has shown varied results on postoperative outcomes. Indeed, a number of studies have suggested octogenarians are at an increased risk of complications,14-16 mortality, 14-16 and prolonged LOS following anterior cervical spine surgery.15,17 Contrary, other studies have demonstrated that octogenarians have outcomes similar to those observed in younger patients.18,19 Such discrepancies in the current literature highlight the need for further analysis of the impact octogenarian age status has on postsurgical outcomes and healthcare resource utilization so as to allow for risk-stratification and optimization of healthcare delivery.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether octogenarian age status is an independent predictor of non-routine discharge and extended LOS following ACDF for CSM.

Methods

Data Source and Patient Population

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database is a stratified discharge database representing 20% of all inpatient admissions from community hospitals in the United States. It is the largest all-payer healthcare database in the US, containing over 7 million hospital admissions (approximately 35 million hospitalizations, weighted) per year. A retrospective study was performed using years 2016 and 2017 of the NIS for all adult inpatient admissions undergoing elective, ACDF for CSM.

The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] diagnosis and procedural coding system (PCS) was used to identify patients and their respective comorbidities and surgical interventions. Patients ≥50 years old with a primary diagnosis code of CSM (ICD-10-CM M47.12) were identified. ICD-10-CM procedural codes were then cross-matched to identify patients in the cohort undergoing elective, anterior cervical discectomy with interbody fusion coded by “cervical vertebral joint fusion with an interbody fusion device” (ICD-10-PCS 0RG10A0, 0RG20A0). Patients with coding for posterior cervical fusion and/or “cervical spinal cord release” (representing laminectomy), a history of traumatic spine fracture or spinal malignancy were excluded (Online Appendix Table A). Patients were then stratified by age: 50 to 64 years-old, 65 to 79 years-old, and greater than or equal to 80 years-old. Informed consent was not necessary due to deidentification of patients in the NIS database. Institutional Review Board approval was not necessary due to deidentification of patients in the NIS database.

Data Collection

Patient demographic information, comorbidities and treating hospital characteristics were collected (Online Appendix Table B). Demographic information included age, gender, median household income quartile and expected primary payer. Hospital characteristics included the region of the hospital, size by bed volume, and teaching status. Elixhauser comorbidities were used to evaluate incidence of congestive heart failure (CHF), cardiac arrhythmia, valvular disease, hypertension (HTN), paralysis, other neurological disorders, chronic pulmonary disease, uncomplicated diabetes (DM), hypothyroidism, renal failure, rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular disease, coagulopathy, obesity, fluid and electrolyte disorders, and deficiency anemia. Nicotine dependence and presence of affective disorder were also assessed. Data on electrophysiological monitoring, blood transfusion, and perioperative complications was included.

Complications for each admission were collected by indexing additional diagnoses. Complications investigated included acute post-hemorrhagic anemia, dysphagia, displacement of internal fixation device of vertebrae, wound disruption, mechanical device complication, hematoma formation, nervous system complication, acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and anesthesia-related complications. We then assessed the patient outcomes of discharge disposition and total cost of hospital admission. Disposition was stratified by routine (home), non-routine (Short-term hospital, skilled nursing facility, intermediate care facility, home with healthcare services), and other (leaving against medical advice, died in hospital, unknown destination). All-payer inpatient cost-to-charge ratios (CCR) were used to convert total hospital charge to total cost of hospital services.

Statistical Analysis

Discharge-level weights were used to calculate national estimates. Parametric data was expressed as mean ± SD and compared via one-way ANOVA test. Nonparametric data was expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared via the Kruskal-Wallis test. Nominal data was compared with the χ2 test. For our primary hypothesis, weighted univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were fitted with extended postoperative hospital LOS (as defined by LOS greater than the 75th percentile for the entire cohort, or >2 days) and non-routine discharge as the dependent variable. There were no patients with missing information on LOS. Patients with “other” discharge were excluded from this portion of the analysis so as to dichotomize routine vs. non-routine discharge. Backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to select variables in the final model, using 0.1 as entry and stay criteria. We forced age, levels fused and complication during admission into the models based on our primary hypothesis, in addition to female sex based on the joint biological association between these covariates and in view of the plausibility for confounding. A P-value of less than 0.05 was determined to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R Studio, Version 3.6.2, RStudio Inc., Boston, MA.

Results

Patient Demographics, Hospital Characteristics, and Comorbidities

There was a total of 14 865 patients who received elective ACDF for CSM, of which 7,910 (53.2%) were 50-64 years-old (Old), 6,480 (43.6%) were 65-79 years-old (Elderly), and 475 (3.2%) were 80+ years of age (Octogenarian), Table 1. The proportion of female patients was significantly lower in the Octogenarian cohort (Old: 50.7% vs. Elderly: 46.4% vs Octogenarian: 42.1%, P = 0.025) as was the proportion of African-American patients (Old: 15.5% vs. Elderly: 9.3% vs Octogenarian: 8.9%, P < 0.001), Table 1. Median household income differed significantly between the cohorts (P = 0.011), particularly within the percentage of patients in the 0-25th income quartile (Old: 26.5% vs. Elderly: 26.3% vs Octogenarian: 15.2%) and the 51-75th income quartile (Old: 27.8% vs. Elderly: 24.6% vs Octogenarian: 35.9%), Table 1. Medical insurance provider also varied significantly between each the cohorts (P < 0.001) as the majority of Octogenarian and Elderly patients were insured by Medicare (93.7% and 83.8%, respectively), while the majority of Old patients were privately insured (54.3%), Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Hospital Characteristics.

| Variables | 50-64 Years (n = 7,910) |

65-79 Years (n = 6,480) |

80+ Years (n = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 57.3 ± 4.2 | 70.5 ± 4.0 | 82.2 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| Median [IQR] | 57 [54–61] | 70 [67–74] | 81.5 [81–83] | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 50.7 | 46.4 | 42.1 | 0.025 |

| Race (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 75.4 | 82.4 | 80.0 | |

| Black | 15.5 | 9.3 | 8.9 | |

| Hispanic | 4.9 | 4.1 | 3.3 | |

| Other | 4.2 | 4.2 | 7.8 | |

| Income Quartile (%) | 0.011 | |||

| 0-25th | 26.5 | 26.3 | 15.2 | |

| 26-50th | 26.8 | 26.1 | 30.4 | |

| 51-75th | 27.8 | 24.6 | 35.9 | |

| 76-100th | 18.8 | 22.9 | 18.5 | |

| Healthcare Coverage (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Medicare | 22.4 | 83.8 | 93.7 | |

| Medicaid | 14.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| Private Insurance | 54.3 | 12.6 | 6.3 | |

| Other | 9.2 | 3.3 | 0.0 | |

| Elective (%) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Hospital Demographics | ||||

| Hospital Bed Size (%) | 0.340 | |||

| Small | 21.0 | 20.2 | 24.2 | |

| Medium | 25.5 | 28.2 | 30.5 | |

| Large | 53.4 | 51.5 | 45.3 | |

| Hospital Region (%) | 0.030 | |||

| Northeast | 12.0 | 10.3 | 16.8 | |

| Midwest | 19.5 | 16.5 | 12.6 | |

| South | 46.1 | 51.2 | 52.6 | |

| West | 22.3 | 22.1 | 17.9 | |

| Hospital Type (%) | 0.132 | |||

| Rural | 2.8 | 1.9 | 5.3 | |

| Urban Non-Teaching | 25.1 | 25.2 | 17.9 | |

| Urban Teaching | 72.1 | 72.9 | 76.8 | |

There was no significant difference between the different cohorts in the size of the hospital where patients received ACDF for CSM, with the majority of each group treated at large hospitals (Old: 53.4% vs. Elderly: 51.5% vs Octogenarian: 45.3%, P = 0.340), Table 1. While the majority of patients were treated in southern hospitals (Old: 46.1% vs. Elderly: 51.2% vs Octogenarian: 52.6%), there was a significant difference between the 3 cohorts in the region of the hospital where patients were treated (P = 0.030), Table 1. No significant difference in the type of hospital (e.g. rural, urban non-teaching, and urban teaching) where patients were treated was observed between the 3 cohorts (P = 0.132), and the majority of patients within each cohort were treated at urban teaching hospitals (Old: 72.1% vs. Elderly: 72.9% vs Octogenarian: 76.8%), Table 1.

Between the cohorts, a significant difference was found in the proportion of patients with affective disorder (Old: 29.3% vs. Elderly: 23.5% vs Octogenarian: 18.9%, P < 0.001), obesity (Old: 18.9% vs. Elderly: 14.3% vs Octogenarian: 12.6%, P < 0.002), and nicotine dependence (Old: 22.0% vs. Elderly: 9.9% vs Octogenarian: 4.2%, P < 0.001), with the highest prevalence among the Old age cohort and the lowest prevalence among the Octogenarian age cohort for each comorbidity, Table 2. A significant difference was also found in the proportion of patients with cardiac arrhythmias (Old: 3.7% vs. Elderly: 10.0% vs Octogenarian: 21.1%, P < 0.001), valvular disease (Old: 2.0% vs. Elderly: 3.0% vs Octogenarian: 11.6%, P < 0.001), hypertension (Old: 56.2% vs. Elderly: 69.1% vs Octogenarian: 73.7%, P < 0.001), and renal failure (Old: 3.3% vs. Elderly: 7.9% vs Octogenarian: 12.6%, P < 0.001), with the prevalence of each decreasing along with age, Table 2. Significant differences in the prevalence of congestive heart failure (Old: 2.1% vs. Elderly: 4.6% vs Octogenarian: 3.2%, P = 0.001), diabetes (Old: 16.4% vs. Elderly: 21.0% vs Octogenarian: 15.8%, P < 0.001), and hypothyroidism (Old: 10.9% vs. Elderly: 16.7% vs Octogenarian: 15.8%, P < 0.001), were reported, with the highest rate of each morbidity observed in Elderly patients, Table 2. Other relevant comorbidities including chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular disease, deficiency anemias, paralysis, and other neurological disorders were found in similar proportions of patients between the different cohorts, Table 2. Less than 10 patients in the Octogenarian cohort and 0.8% of patients in Old and Elderly cohorts, respectively, had coagulopathy or fluid/electrolyte disorders, Table 2.

Table 2.

Admission and Patient Comorbidities.

| Variables (%) | 50-64 Years (n = 7,910) |

65-79 Years (n = 6,480) |

80+ Years (n = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective disorder | 29.3 | 23.5 | 18.9 | <0.001 |

| Nicotine dependence | 22.0 | 9.9 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.1 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 3.7 | 10.0 | 21.1 | <0.001 |

| Valvular disease | 2.0 | 3.0 | 11.6 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, combined | 56.2 | 69.1 | 73.7 | <0.001 |

| Paralysis | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 0.408 |

| Other neurological disorders | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 0.664 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 20.6 | 21.1 | 15.8 | 0.472 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 16.4 | 21.0 | 15.8 | 0.005 |

| Hypothyroidism | 10.9 | 16.7 | 15.8 | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 3.3 | 7.9 | 12.6 | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/ collagen vascular diseases | 4.0 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 0.691 |

| Coagulopathy | 0.8 | 0.8 | N < 10* | - |

| Obesity | 18.9 | 14.3 | 12.6 | 0.002 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 3.0 | 6.0 | N < 10* | - |

| Deficiency anemias | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 0.454 |

* Signifies that the count number is <10 and cannot be reported.

Intraoperative Variables, Postoperative Complications, and Postoperative Inpatient Outcomes

There was no significant difference between the cohorts regarding intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring (Old: 26.0% vs. Elderly: 25.4% vs Octogenarian: 23.2%, P = 0.792) or incidences of intraoperative dural tears and cerebrospinal fluid leaks (Old: 0.5% vs. Elderly: 0.5% vs Octogenarian: 0.0%, P = 0.778), Table 3.The Old and Elderly cohorts had higher reported rates of spinal fusions of two or more levels than Octogenarian patients (Old: 77.9% vs. Elderly: 75.2% vs Octogenarian: 61.1%, P = 0.001), Table 3.

Table 3.

Intraoperative Variables.

| Variables (%) | 50-64 Years (n = 7,910) |

65-79 Years (n = 6,480) |

80+ Years (n = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophysiological monitoring | 26.0 | 25.4 | 23.2 | 0.792 |

| Fusion Levels | 0.001 | |||

| One level | 22.1 | 24.8 | 38.9 | |

| Two levels or more | 77.9 | 75.2 | 61.1 | |

| Complications | ||||

| Cerebrospinal fluid leak or dural tear |

0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.778 |

* Signifies that the count number is <10 and cannot be reported.

The proportion of patients who experienced any postoperative complication differed significantly between the cohorts and decreased with age, from 18.9% of Octogenarians to 12.6% of Elderly patients and 10.2% of Old patients (P = 0.048), Table 4. Of the Octogenarian patients, 17.9% had 1 complication and 1.1% had >1; of the Elderly patients, 11.7% had 1 complication and 0.9% had >1; of the Old patients, 9.4% had 1 complication and 0.8% had >1 (P = 0.048), Table 4. The most common complication for each of the cohorts was dysphagia and the rate of occurrence was significantly different between the 3 cohorts (Old: 7.2% vs. Elderly: 9.5% vs Octogenarian: 17.9%, P < 0.001), Table 4. No significant difference was observed between the 3 cohorts in regard to incidence rate of the postoperative complications: acute post-hemorrhagic anemia (P = 0.918), displacement of internal fixation device of vertebrae (P = 0.916), mechanical device complications (P = 0.727), hematoma (P = 0.716), acute deep vein thrombosis (P = 0.917), and any other nervous system complication (P = 0.255), Table 4. Less than 10 patients in the Old and Elderly cohorts had complications related to wound disruption and 0% of Octogenarians reported any postoperative wound complications, Table 4.

Table 4.

Postoperative Complications.

| Variables (%) | 50-64 Years (n = 7,910) |

65-79 Years (n = 6,480) |

80+ Years (n = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute post-hemorrhagic anemia |

2.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 0.918 |

| Dysphagia | 7.2 | 9.5 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

| Displacement of internal fixation device of vertebrae | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.916 |

| Wound disruption | N<10* | N<10* | 0.0 | - |

| Mechanical device complication | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.727 |

| Hematoma | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.716 |

| Nervous system complication | N<10* | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.255 |

| Acute deep vein thrombosis | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.917 |

| Any complication | 10.2 | 12.6 | 18.9 | 0.008 |

| Number of Complications | 0.048 | |||

| 0 | 89.8 | 87.4 | 81.1 | |

| 1 | 9.4 | 11.7 | 17.9 | |

| >1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

* Signifies that the count number is <10 and cannot be reported.

The mean LOS was largest among Octogenarian patients and differed significantly between the 3 cohorts (Old: 2.0 ± 2.4 days vs. Elderly: 2.2 ± 2.8 vs Octogenarian: 2.3 ± 2.1, P = 0.028), Table 5. The proportion of patients who experienced an extended LOS was also highest among Octogenarians and, compared between the 3 cohorts, differed significantly (Old: 18.3% vs. Elderly: 21.9% vs Octogenarian: 28.4%, P = 0.009), Table 5. The rate of non-routine discharge differed significantly between the cohorts and was greatest for Octogenarian patients (35.8%) when compared to Elderly (23.0%) and Old (15.1%) patients (P < 0.001), Table 5. There was no significant difference observed in the mean (P = 0.172) or median (P = 0.113) total cost of hospital admission between the 3 cohorts, Table 5.

Table 5.

Postoperative Inpatient Outcomes.

| Variables | 50-64 Years (n = 7,910) |

65-79 Years (n = 6,480) |

80+ Years (n = 475) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay (days) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.0 ± 2.4 | 2.2 ± 2.8 | 2.3 ± 2.1 | 0.028 |

| Median [IQR] | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–2] | 2 [1–3] | 0.001 |

| Extended LOS (%) | 18.3 | 21.9 | 28.4 | 0.009 |

| Total Cost of Admission ($) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 20,078 ± 10,668 | 20,128 ± 12,969 | 18,208 ± 9,905 | 0.172 |

| Median [IQR] | 17,678 [13,257–23,480] | 17,377 [12,956–23,104] | 16,197 [12,914–22,233] | 0.113 |

| Disposition (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Routine | 84.6 | 76.6 | 64.2 | |

| Non-Routine | 15.1 | 23.0 | 35.8 | |

| Other | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

Logistic Multivariate Regression Analysis for Extended LOS

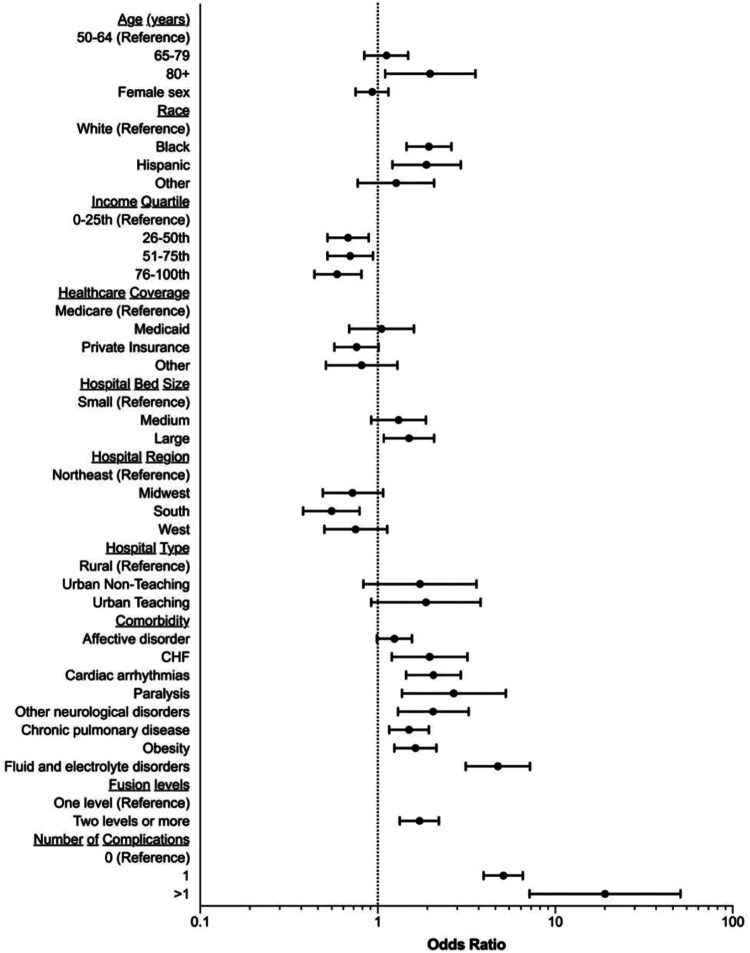

On multivariate regression analysis with the Old cohort used as a reference, Octogenarians were associated with an extended LOS after elective ACDF for CSM, [OR: 1.97, 95% CI: (1.10, 3.55), P = 0.023], while Elderly patients demonstrated no significant increase in the likelihood of an experiencing an extended LOS in the hospital [OR: 1.12, 95% CI: 0.84, 1.48), P = 0.436], Table 6, Figure 1. Other patient demographics associated with an increased risk of an extended LOS included being Black (P < 0.001) or Hispanic (P = 0.005), Table 6, Figure 1. Females were not found to be at a significantly greater risk of an extended LOS than males (P = 0.488), Table 6, Figure 1. Comorbidities such as congestive heart failure (P = 0.007), cardiac arrythmias (P < 0.001), paralysis (P = 0.004), other neurological disorders (P = 0.002), chronic pulmonary disease (P = 0.002), obesity (P < 0.001), and fluid or electrolyte disorders (P < 0.001) were also significant risk-factors associated with an extended LOS, Table 6, Figure 1. A prior diagnosis of affective disorder was the only comorbidity analyzed that was not found to increase the risk of experiencing an extended LOS (P = 0.060), Table 6, Figure 1. Other comorbidities such as hypertension, hypothyroidism, renal failure, and coagulopathy were excluded from multivariate regression analysis, Table 6. Intraoperatively, compared to a single level of spinal fusion, two or more levels were found to be a risk factor for extended LOS [OR: 1.72, 95% CI: (1.33, 2.21), P < 0.001], Table 6, Figure 1. Compared to no complications, experiencing 1 complication was also found to be a significant risk-factor associated with extended LOS, with an OR of 5.10 [95% CI: (3.95, 6.57), P < 0.001] Table 6, Figure 1. Experiencing >1 postoperative complication was associated with an even greater risk of an extended LOS than 1 complication when both conditions were independently compared to experiencing no complications [OR: 19.08, 95% CI: (7.16, 50.87), P < 0.001] Table 6, Figure 1. Receiving surgery in a large (P = 0.016) or southern hospital (P = 0.001) was also associated with an increased risk of experiencing an extended LOS, while choice of medical insurance provider was not, Table 6, Figure 1.

Table 6.

Logistic Multivariate Regression Analysis on Extended Length of Stay.a

| Univariate model | Multivariate model | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 50-64 | REFERENCE | ||

| 65-79 | 1.26 (1.04, 1.52) | 1.12 (0.84, 1.48) | 0.436 |

| 80+ | 1.78 (1.11, 2.85) | 1.97 (1.10, 3.55) | 0.023 |

| Female sex | 0.98 (0.82, 1.18) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.15) | 0.488 |

| Race | |||

| White | REFERENCE | ||

| Black | 1.95 (1.50, 2.54) | 1.94 (1.45, 2.60) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.92 (1.29, 2.85) | 1.88 (1.21, 2.94) | 0.005 |

| Other | 1.14 (0.73, 1.79) | 1.27 (0.77, 2.08) | 0.348 |

| Income Quartile | |||

| 0-25th | REFERENCE | ||

| 26-50th | 0.67 (0.52, 0.86) | 0.68 (0.52, 0.89) | 0.006 |

| 51-75th | 0.71 (0.55, 0.91) | 0.70 (0.52, 0.94) | 0.018 |

| 76-100th | 0.63 (0.47, 0.84) | 0.59 (0.44, 0.81) | 0.001 |

| Healthcare Coverage | |||

| Medicare | REFERENCE | ||

| Medicaid | 1.16 (0.83, 1.61) | 1.05 (0.69, 1.60) | 0.834 |

| Private Insurance | 0.65 (0.53, 0.79) | 0.76 (0.57, 1.01) | 0.055 |

| Other | 0.79 (0.53, 1.16) | 0.81 (0.51, 1.29) | 0.377 |

| Hospital Bed Size | |||

| Small | REFERENCE | ||

| Medium | 1.33 (0.95, 1.86) | 1.31 (0.92, 1.87) | 0.132 |

| Large | 1.67 (1.22, 2.29) | 1.50 (1.08, 2.08) | 0.016 |

| Hospital Region | |||

| Northeast | REFERENCE | ||

| Midwest | 0.90 (0.62, 1.30) | 0.72 (0.49, 1.07) | 0.103 |

| South | 0.65 (0.46, 0.91) | 0.55 (0.38, 0.79) | 0.001 |

| West | 0.83 (0.57, 1.21) | 0.75 (0.50, 1.13) | 0.167 |

| Hospital Type | |||

| Rural | REFERENCE | ||

| Urban Non-Teaching | 1.62 (0.86, 3.06) | 1.73 (0.83, 3.60) | 0.144 |

| Urban Teaching | 1.97 (1.07, 3.62) | 1.87 (0.92, 3.80) | 0.083 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Affective disorder | 1.35 (1.11, 1.65) | 1.24 (0.99, 1.56) | 0.060 |

| Congestive heart failure |

2.75 (1.80, 4.20) | 1.96 (1.20, 3.20) | 0.007 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 2.89 (2.14, 3.90) | 2.06 (1.44, 2.94) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, combined | 1.48 (1.23, 1.79) | Removed | |

| Paralysis | 3.43 (1.79, 6.57) | 2.68 (1.37, 5.27) | 0.004 |

| Other neurological disorders |

2.88 (1.91, 4.33) | 2.05 (1.30, 3.25) | 0.002 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

1.57 (1.26, 1.96) | 1.50 (1.16, 1.94) | 0.002 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.39 (1.08, 1.78) | Removed | |

| Renal failure | 2.22 (1.61, 3.06) | Removed | |

| Coagulopathy | 2.66 (1.19, 5.95) | Removed | |

| Obesity | 1.84 (1.46, 2.32) | 1.63 (1.24, 2.14) | <0.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders |

6.50 (4.54, 9.32) | 4.75 (3.13, 7.20) | <0.001 |

| Fusion Levels | |||

| One level | REFERENCE | ||

| Two levels or more | 1.52 (1.22, 1.91) | 1.72 (1.33, 2.21) | <0.001 |

| Number of Complications | |||

| 0 | REFERENCE | ||

| 1 | 5.94 (4.65, 7.59) | 5.10 (3.95, 6.57) | <0.001 |

| >1 | 22.56 (8.21, 61.96) | 19.08 (7.16, 50.87) | <0.001 |

aBold indicates statistical significance was met on the univariate and multivariate analyses respectively.

Figure 1.

Forest plot representing odds ratios for the multivariate regression analysis on extended length of stay.

Logistic Multivariate Regression Analysis for Non-Routine Discharge

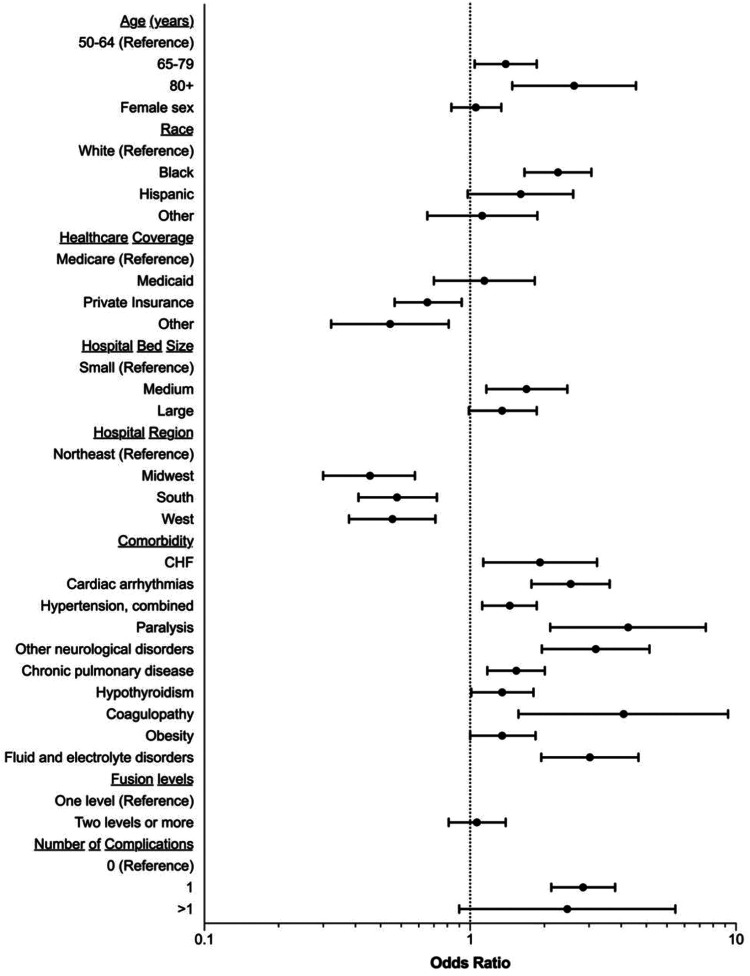

Compared to the Old patient cohort, Elderly and Octogenarian patients were found to have an increased risk of experiencing a non-routine discharge from the hospital, with respective ORs of 1.36 [95% CI: (1.04, 1.78), P < 0.027] and 2.46 [95% CI: (1.44, 4.21), P = 0.001], Table 7, Figure 2. Black race was associated with an increased risk of non-routine discharge (P < 0.001), while being female (P = 0.624), Hispanic (P = 0.061), or another unclassified race (P = 0.669) were not found to be risk-factors, Table 7, Figure 2. Compared to patients insured by Medicare, patients who received insurance from private (P = 0.014) or other organizations (P = 0.008) were at a greater risk of non-routine discharge, while patients insured by Medicaid were not (P = 0.588) Table 7, Figure 2. Comorbidities associated with an greater risk of non-routine discharge included congestive heart failure (P = 0.017), cardiac arrhythmias (P < 0.001), hypertension (P = 0.004), paralysis (P < 0.001), other neurological disorders (P < 0.001), chronic pulmonary disease (P = 0.002), hypothyroidism (P = 0.046), coagulopathy (P = 0.004), and fluid and electrolyte disorders (P < 0.001), Table 7, Figure 2. Obesity was found to not be a significant risk-factor for non-routine discharge following ACDF for CSM (P = 0.053), Table 7, Figure 2. Comorbidities excluded from multivariate analysis included affective disorder, diabetes, and renal failure, Table 7. Two levels of spinal fusion, as compared to one, was also not a significant risk factor for non-routine discharge (P = 0.637), Table 7, Figure 2. Compared to no complications, experiencing 1 complication was found to be a significant risk-factor for non-routine discharge, with an OR of 2.66 [95% CI: (2.02, 3.51), P < 0.001], but experiencing >1 complication was not considered a risk-factor, with an OR of 2.32 [95% CI: (0.91, 5.92), P < 0.077], Table 7, Figure 2. Being treated in a midwest (P < 0.001), southern (P < 0.001), or western hospital (P < 0.001), were found to be risk-factors for non-routine discharge when compared being treated in northeastern hospitals, Table 7, Figure 2. Compared to small hospitals, being treated at a medium sized hospital (P = 0.006) posed a significant risk to having a non-routine discharge, while large hospitals did not (P = 0.063), Table 7, Figure 2.

Table 7.

Logistic Multivariate Regression Analysis on Non-Routine Discharge.a

| Univariate model | Multivariate model | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 50-64 | Reference | ||

| 65-79 | 1.69 (1.39, 2.04) | 1.36 (1.04, 1.78) | 0.027 |

| 80+ | 3.13 (2.03, 4.84) | 2.46 (1.44, 4.21) | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.06 (0.88, 1.29) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.31) | 0.624 |

| Race | |||

| White | Reference | ||

| Black | 2.06 (1.60, 2.65) | 2.14 (1.60, 2.86) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.53 (1.03, 2.27) | 1.55 (0.98, 2.44) | 0.061 |

| Other | 0.97 (0.61, 1.56) | 1.11 (0.69, 1.79) | 0.669 |

| Income Quartile | |||

| 0-25th | Reference | ||

| 26-50th | 0.77 (0.60, 0.99) | Removed | |

| 51-75th | 0.94 (0.73, 1.21) | Removed | |

| 76-100th | 0.93 (0.70, 1.23) | Removed | |

| Healthcare Coverage | |||

| Medicare | Reference | ||

| Medicaid | 0.95 (0.68, 1.33) | 1.13 (0.73, 1.75) | 0.588 |

| Private Insurance | 0.46 (0.36, 0.58) | 0.69 (0.52, 0.93) | 0.014 |

| Other | 0.42 (0.27, 0.67) | 0.50 (0.30, 0.83) | 0.008 |

| Hospital Bed Size | |||

| Small | Reference | ||

| Medium | 1.64 (1.18, 2.28) | 1.63 (1.15, 2.32) | 0.006 |

| Large | 1.41 (1.07, 1.87) | 1.32 (0.99, 1.78) | 0.063 |

| Hospital Region | |||

| Northeast | Reference | ||

| Midwest | 0.51 (0.36, 0.73) | 0.42 (0.28, 0.62) | <0.001 |

| South | 0.59 (0.43, 0.80) | 0.53 (0.38, 0.75) | <0.001 |

| West | 0.53 (0.38, 0.74) | 0.51 (0.35, 0.74) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Affective disorder | 1.29 (1.05, 1.58) | Removed | |

| Congestive heart failure | 3.03 (1.97, 4.67) | 1.83 (1.12, 3.00) | 0.017 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 3.29 (2.45, 4.41) | 2.39 (1.70, 3.35) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, combined | 1.88 (1.53, 2.32) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.78) | 0.004 |

| Paralysis | 4.82 (2.49, 9.31) | 3.93 (2.00, 7.70) | <0.001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 3.59 (2.38, 5.43) | 2.97 (1.86, 4.73) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.57 (1.26, 1.95) | 1.49 (1.16, 1.91) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 1.45 (1.17, 1.79) | Removed | |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.49 (1.18, 1.88) | 1.32 (1.01, 1.73) | 0.046 |

| Renal failure | 2.54 (1.84, 3.51) | Removed | |

| Coagulopathy | 6.00 (2.64, 13.60) | 3.78 (1.52, 9.35) | 0.004 |

| Obesity | 1.56 (1.22, 1.99) | 1.32 (1.00, 1.76) | 0.053 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders |

4.35 (3.05, 6.21) | 2.82 (1.85, 4.30) | <0.001 |

| Fusion Levels | |||

| One level | Reference | ||

| Two levels or more | 0.99 (0.79, 1.23) | 1.06 (0.83, 1.36) | 0.637 |

| Number of Complications | |||

| 0 | Reference | ||

| 1 | 3.16 (2.47, 4.05) | 2.66 (2.02, 3.51) | <0.001 |

| >1 | 3.66 (1.55, 8.64) | 2.32 (0.91, 5.92) | 0.077 |

aBold indicates statistical significance was met on the univariate and multivariate analyses respectively.

Figure 2.

Forest plot representing odds ratios for the multivariate regression analysis on non-routine discharge.

Discussion

In this national, retrospective NIS database study of 14 865 geriatric patients who underwent elective ACDF for CSM, we demonstrate that Octogenarians are at a significantly higher risk of experiencing post-operative complications, prolonged LOS, and nonroutine discharge.

Within the literature, there has been efforts to determine the rates of perioperative complications following spinal surgery on Octogenarian patients. In a retrospective analysis of NIS data collected from 1993 to 2003, Boakye et al. found that CSM patients aged ≥85 years had 5.1 times greater odds of experiencing complications from surgical fusion than CSM patients aged 18 to 44 years and more than double the odds of complication than patients aged 65 to 84 years. 14 In a retrospective cohort study of 6,253 patients who underwent ACDF, Buerba et al. showed that ≥75-year-old patients have 2.8 times greater odds of adverse outcomes than patients between the ages of 40 and 74 years. 15 Similarly, in a retrospective analysis of 57 323 patients undergoing ACDF surgery in the NIS database, Puvanesarajah et al. found that Octogenarians had 1.6 times greater odds of experiencing complications than patients aged 65 to 79 years. 16 Similar to the findings in the aforementioned studies, our study found that the prevalence of postoperative complications was significantly higher among Octogenarians than the rest of the cohort.

The cause of this age-related discrepancy in the rate of complication after ACDF is likely multifactorial, arising secondary to the natural aging process and increased incidence rate of high-risk comorbidities.16,20 This was shown in the study by Puvanesarajah et al., which demonstrated that on average, each octogenarian patient had significantly more comorbidities than younger age patients undergoing ACDF. 16 The effect of multiple, compounding comorbidities, is likely an important contributor to complication development. 21 In our study, dysphagia was the most common complication seen to disproportionately affect octogenarian patients. Increased rates of post-ACDF dysphagia in the aging population have consistently been reported by multiple independent groups.16,22,23 Additionally, Puvanesarajah et al. noted higher reintubation and aspiration pneumonia rates in octogenarian patients, 2 factors previously demonstrated to closely associate with later dysphagia development after ACDF.16,24 These results suggest octogenarians may be more naturally prone to post-ACDF dysphagia, with the frequency exacerbated by other common perioperative events. Interestingly, in the study by Buerba et al., the authors highlighted high rates of urinary complications, citing age as a significant risk factor for urinary retention after ACDF procedure.15,25 The group suggested this increase in urinary complication frequency resulted from higher rates of preoperative risk-factors such as diabetes and prostate comorbidities among patients aged 75 years or older. 15 While our study did not tabulate incidence of prostate comorbidities or postoperative urinary complication rates, our study found that diabetes was actually significantly less common among octogenarians when compared to old and elderly patients. However, octogenarian patients included in our study did have significantly higher rates of renal failure, which may predispose to postoperative urinary complication. These results indicate that natural aging and higher rates of preexisting comorbidities among advanced-age patients both play key roles in the development of complications. Given these considerations, it is important to note that our octogenarian patients had significantly higher rates of just 4 of the 17 reported comorbidities: cardiac arrythmias, valvular disease, hypertension, and renal failure. While this does not address the possibility of compounding comorbidities, these results indicate that dysregulation in heart and/or hemostatic blood pressure regulation may be a critical predictor of ACDF outcomes. This multifactorial hypothesis for complications in advanced age patients is supported in other major surgeries. 26 Despite these indications, further controlled studies are still required to best elucidate the underlying factors that contribute to the observed discrepancies in complication rates between these age groups.

In addition to greater risks of postoperative complications, increased prevalence of mortality in Octogenarians remains a critical issue in anterior cervical spine surgery. In the study by Boakye et al., patients aged ≥85 years were found to have a 44-fold increase in rates of mortality following spinal fusion for CSM compared to patients in the 18- to 44-year-old age group. 14 These odds were significantly higher than the odds of mortality faced by 65 to 84-year-old patients (14-fold increase). 14 Similarly, in the study by Buerba et al., ≥75-year-old patients were demonstrated to have an 8 times greater chance of experiencing mortality than patients aged 40 to 64 years. 15 Moreover, Buerba et al. also observed that there was no increase in mortality for patients aged 60 to 74 years when compared to patients between the ages of 40 and 64 years. Lastly, in the study by Puvanesarajah et al., octogenarians were found to be at 4 times greater odds of mortality than patients aged 65 to 79. 16 One could postulate that the observed increase in mortality rates may not be attributable to the ACDF procedure in itself, but rather the overall state of health of the patient presents with. The octogenarian cohort has at a baseline increased rates of significant comorbidities that are likely chronic in nature, and therefore have already taken an effect on the patients’ overall health compliance—thus increasing rate of mortality. 20 Nonetheless, further studies could identify possible explanations for why octogenarian patients experience such high mortality rates that are specific to the ACDF procedure. Additionally, risk-benefit stratifications may be warranted in this patient population.

Previous studies have attempted to find associations between old age and LOS after elective spine surgery. In the study by Buerba et al., when compared to patients between the age of 40 to 64 years old, the authors demonstrated that patients aged ≥75 years had considerably greater odds of experiencing a prolonged LOS after ACDF than 65- to 74-year-old patients. 15 Similarly, in a retrospective analysis of the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan Research Databases between 2000 and 2012, Lagman et al. showed that patients aged 80 to 103 years were significantly more likely than patients aged 18 to 79 years to experience a prolonged LOS (3.62 days vs. 3.11 days) after decompression and/or fusion surgery to correct degenerative spinal disease or spinal stenosis. 27 Furthermore, in a retrospective, observational study of 134 088 patients who underwent ACDF in 2011, Kalakoti et al. found that patients aged 80 to 95 years experienced significantly longer LOS (+0.16 days) than patients aged 60 to 79 years (+0.06), with patients of <60 years of age used as a reference group. 17 Similar to the aforementioned studies, our analysis demonstrated that octogenarians were at the greatest risk for an extended LOS. With much of the existing literature classifying patients as >65- or <65-years-old, more studies that analyze LOS after spinal surgery in further age-stratified groups of geriatric patients are needed to better understand the potential impact advanced aging has on spinal operation outcomes. The increase in the LOS for the octogenarian cohort is likely attributable to the temporal delay in post-operative recovery—pain control, ambulation and oral intake. All of which have implications on the time in the hospital.

In addition to analyzing LOS, other healthcare proxy metrics, such as discharge disposition, have been used to assess surgical outcomes in advanced aged patients following spinal surgery procedures. However, there is a paucity of studies analyzing this metric after spinal surgery in geriatric patients further stratified by age group, with most studies broadly comparing younger patients to those over the age of 60 or 65. Of these studies, geriatric patients have been noted to have significantly higher rates of nonroutine discharge. For example, in a retrospective review of 15 624 patients who underwent ACDF, Malik et al. demonstrated that an age of ≥65 years was a significant predictor of discharge to a skilled care or rehabilitation facility. 28 Our study found similar results, with elderly patients having significantly increased odds of nonroutine discharge when compared to old patients. Moreover, our further age-stratified dataset allowed for the determination that a significantly greater proportion of octogenarians experienced nonroutine discharge than both old and elderly patients. These results indicate the risk of nonhome discharge continues to increase past the age of 65, underscoring the importance for increased research focusing exclusively on all operation outcomes in stratified groups of geriatric patients.

Increased rates of post-operative complications in geriatric patients may be contributing to the longer LOS and more frequent nonroutine discharges following anterior cervical spinal surgery. In a retrospective cohort study of 14 602 patients, Di Capua et al. found that the best predictor of nonroutine discharge after ACDF was experiencing a postoperative complication. 29 In another retrospective cohort study of 15 600 patients treated with ACDF or ACCF, Katz et al. found an association between complications and extended LOS, suggesting a bidirectional relationship where complications may result in prolonged LOS and prolonged LOS may increase the frequency of nosocomial complications. 30 Moreover, as shown in Malik et al., prolonged LOS is often associated with nonhome discharge. 28 Similarly, our study found that experiencing one complication led to significantly increased odds of nonroutine discharge and extended LOS. Interestingly, however, our study found more than one complication did not result in significantly increased odds of nonroutine discharge but was associated with experiencing an extended LOS. This data suggests a possible positive correlation between increased complications, which was observed in octogenarians, and an increased likelihood of prolonged LOS. Comorbidities, which as previously discussed are strongly linked to complication occurrence, may also be significant predictors of prolonged LOS and nonroutine discharge. Three of the 4 morbidities that most strongly afflicted octogenarian patients (renal failure, hypertension, cardiac arrythmias), were independently shown to predict extended LOS or nonroutine discharge. The fourth, valvular disease, was not analyzed. Future studies are needed to better assess the relationship between surgical complication, comorbidity, extended LOS and nonroutine discharge, as the association may be the driver for inferior patient outcomes and increased healthcare resource utilization.

Given the rapidly aging population in the United States and the established higher rates of prolonged LOS and complications observed in Octogenarian patients, studies have attempted to assess the potential burden of Octogenarian patients undergoing ACDF on healthcare costs. In a multi-institutional retrospective study of 49 300 patients who underwent cervical spinal fusion, Joseph et al. reported that patients with post-ACDF dysphagia, the outlier accounting for the majority of octogenarian complications, had to pay $21 245 dollars in direct hospital costs while non-dysphagia patients paid $13 099. 31 In Kalakoti et al., patients aged 80 to 95 years had greater healthcare costs following fusion procedures than patients of <60 years by a meager margin (+$561). 17 Although the increase in cost among those aged 80 to 95 was insignificant in Kalakoti et al., they also determined patients with preexisting comorbidities, similar to our octogenarian cohort, had significantly increased costs of care than patients without comorbidities. 17 However, despite these findings, our study determined octogenarians did not significantly differ from old and elderly patients in cost of hospital admission. While the reasons for this observation are currently unclear, studies that observed similar findings have attempted to better understand why healthcare costs are similar. For example, in Buerba et al., patients aged ≥75 years had significantly shorter, and therefore cheaper, OR times, potentially offsetting increased costs imposed by longer LOS. 15 Other studies have suggested payment modality to be the cause of these observation as it is estimated that private payers have nearly double the amount of direct healthcare costs than those supported by government systems. 32 This potentially mirrors what is observed in our study, as significantly more old (54.3%) and elderly (12.6%) patients were privately insured than octogenarians (6.3%), who were primarily insured by Medicare (93.7%). While this may offer an explanation as to why costs were lowest among octogenarians despite expenditures imposed by increased LOS and higher complication rates, further studies are necessary to better elucidate the reasons for these findings.

Given the soaring cost healthcare in the United States healthcare systems and policymakers are increasing efforts to mitigate expenditures. One strategy that is believed to help mitigate the cost of healthcare, is to reduce the length of time patients spend in the hospital. In a retrospective cohort study of 465 patients undergoing ACDF at a single institution, Reese et al. demonstrated that extended LOS was the most important factor for increasing costs of ACDF procedures. 33 Moreover, in a retrospective analysis of 450 patients, Chotai et al. showed that total hospital-related expenditures increased by $2,216 with each additional day spent in the hospital after ACDF for cervical spine degeneration. 34 Additionally, in a retrospective analysis of 35 962 CSM patients, Veeravagu et al. demonstrated that complications were a significant driver of healthcare costs following ACDF or other fusion procedures. 35 Given these studies, LOS is considered to be closely associated increased hospital expenditures for spinal surgery—therefore, reducing hospital LOS may significantly reduce hospital resource utilization.

Although octogenarian patients have significantly higher rates of complication, mortality, prolonged LOS, and nonroutine discharge after ACDF, there is evidence to suggest that many octogenarian patients may still greatly benefit from the procedure. In a multicenter prospective study of 479 patients who underwent various modalities of decompressive surgery for CSM, Nakashima et al. demonstrated that most geriatric patients achieve functionally significant improvement by 24-months after surgery. 19 Furthermore, in a prospective study of 369 patients being treated for CSM, Yoshida et al. found that locomotor improvement was significantly greater among patients aged ≥75 years than those <75 years of age. 18 Currently, there is a lack of studies that focus on long-term improvement of octogenarian patients as compared to other geriatric patients in spinal surgery, with much of the literature focused on rates of perioperative complication. Future longitudinal studies that analyze motor and sensory metrics before surgery, before discharge, and in the months or years following surgery should be conducted to better understand how octogenarian patients respond to ACDF and other spinal operations. Overall further necessitating a risk-benefit stratification for octogenarians presenting with CSM requiring ACDF. In creating such stratifications would also help identify risk-factors for adverse outcomes that could be used to establish criteria for when and when not to do surgery. This may reduce healthcare costs by avoiding surgeries where the risk of operating outweighs the potential benefit, which typically lead to long, expensive hospital courses and nonhome discharges.

This study has several inherent limitations that may impact how the data is interpreted. First, the study was a retrospective analysis of a national database, lending way to the possibility of inaccurate or biased recordkeeping. Second, as patients in the NIS database are separated by diagnostic codes, there is the potential for misclassified or incomplete data. Third, the NIS only shares information for one inpatient hospital admission, limiting our ability to assess long-term outcomes derived from follow-up appointments. Finally, as the data was collected retrospectively, we are unable to report on some potential confounding factors. For example, while data for many common comorbidities was collected, not all pre-existing conditions that may impact surgical outcomes were considered. Due to these limitations in the study’s design, we are unable to determine whether the discrepancies observed are the result of natural aging or the higher reported incidence of potentially complication-associated comorbidities in Octogenarians. However, despite these limitations, the study broadly demonstrates that advanced-aged patients are at an increased risk for postoperative complications, length of stay and non-routine discharges after undergoing ACDF.

Conclusions

Our study found that Octogenarian patients are at significantly higher risk for experiencing postoperative complications, extended LOS, and nonroutine discharge following ACDF. Risk-stratification and optimized peri- and post-operative management of at-risk patients may allow for improved quality of care and decreased healthcare expenditures.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-gsj-10.1177_2192568221989293 for Octogenarians Are Independently Associated With Extended LOS and Non-Routine Discharge After Elective ACDF for CSM by Aladine A. Elsamadicy, Andrew B. Koo, Benjamin C. Reeves, Isaac G. Freedman, Wyatt B. David, Jeff Ehresman, Zach Pennington, Maxwell Laurans, Luis Kolb and Daniel M. Sciubba in Global Spine Journal

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-2-gsj-10.1177_2192568221989293 for Octogenarians Are Independently Associated With Extended LOS and Non-Routine Discharge After Elective ACDF for CSM by Aladine A. Elsamadicy, Andrew B. Koo, Benjamin C. Reeves, Isaac G. Freedman, Wyatt B. David, Jeff Ehresman, Zach Pennington, Maxwell Laurans, Luis Kolb and Daniel M. Sciubba in Global Spine Journal

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Aladine A. Elsamadicy, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7658-6461

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7658-6461

Isaac G. Freedman, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2603-4201

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2603-4201

Zach Pennington, BS  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8012-860X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8012-860X

Daniel M. Sciubba, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7604-434X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7604-434X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Adogwa O, Lilly DT, Khalid S, et al. Extended length of stay after lumbar spine surgery: sick patients, postoperative complications, or practice style differences among hospitals and physicians? World Neurosurg. 2019;123:e734–e739.[ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercer MP, Singh MK, Kanzaria HK. Reducing emergency department length of stay. JAMA. 2019;321(14):1402–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang J, Upfill-Brown A, Dann AM, et al. Association of hospital length of stay and complications with readmission after open pancreaticoduodenectomy. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(1):88–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gay JC, Hall M, Markham JL, Bettenhausen JL, Doupnik SK, Berry JG. Association of extending hospital length of stay with reduced pediatric hospital readmissions. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(2):186–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stopa BM, Robertson FC, Karhade AV, et al. Predicting nonroutine discharge after elective spine surgery: external validation of machine learning algorithms. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;31:742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yadla S, Ghobrial GM, Campbell PG, et al. Identification of complications that have a significant effect on length of stay after spine surgery and predictive value of 90-day readmission rate. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(6):807–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De la Garza-Ramos R, Goodwin CR, Abu-Bonsrah N, et al. Prolonged length of stay after posterior surgery for cervical spondylotic myelopathy in patients over 65years of age. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;31:137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith GA, Chirieleison S, Levin J, et al. Impact of length of stay on HCAHPS scores following lumbar spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;31(3):366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vonck CE, Tanenbaum JE, Smith GA, Benzel EC, Mroz TE, Steinmetz MP. National trends in demographics and outcomes following cervical fusion for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Glob Spine J. 2018;8(3):244–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein N. Spine surgery in geriatric patients: sometimes unnecessary, too much, or too little. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Lynnger TM, Zuckerman SL, Morone PJ, et al. Trends for spine surgery for the elderly. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(Supp 4):S136–S141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zafrir N, Mats I, Solodky A, Ben-Gal T, Battler A. Characteristics and outcome of octogenarian population referred for myocardial perfusion imaging: comparison with non-octogenarian population with reference to gender. Clin Cardiol. 2006;29(3):117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boakye M, Patil CG, Santarelli J, Ho C, Tian W, Lad SP. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: complications and outcomes after spinal fusion. Neurosurgery 2008;62(2):455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buerba RA, Giles E, Webb ML, Fu MC, Gvozdyev B, Grauer JN. Increased risk of complications after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion in the elderly. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(25):2062–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puvanesarajah V, Jain A, Shimer AL, Singla A, Shen F, Hassanzadeh H. Complications and mortality following one to two-level anterior cervical fusion for cervical spondylosis in patients above 80 years of age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(9):E509–E514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalakoti P, Gao Y, Hendrickson NR, Pugely AJ. Preparing for bundled payments in cervical spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44(5):334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida G, Kanemura T, Ishikawa Y, et al. The effects of surgery on locomotion in elderly patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(11):2545–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakashima H, Tetreault LA, Nagoshi N, et al. Does age affect surgical outcomes in patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy? Results from the prospective multicenter AOSpine International study on 479 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(7):734–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson VB, Jones RS. Surgical risk factors, morbidity, and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6): 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Capua J, Somani S, Kim JS, et al. Elderly age as a risk factor for 30-day postoperative outcomes following elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Glob Spine J. 2017;7(5):425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron EM, Soliman AMS, Simpson L, Gaughan JP, Young WF. Dysphagia, hoarseness, and unilateral true vocal fold motion impairment following anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003. doi:10.1177/000348940311201102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh K, Marquez-Lara A, Nandyala SV, Patel AA, Fineberg SJ. Incidence and risk factors for dysphagia after anterior cervical fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(21):1820–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clavé P, Shaker R. Dysphagia: current reality and scope of the problem. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(5):259–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung HJ, Park JB, Kong CG, Kim YY, Park J, Kim JB. Postoperative urinary retention following anterior cervical spine surgery for degenerative cervical disc diseases. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5(2):134–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lott A, Belayneh R, Haglin J, Konda SR, Egol KA. Age alone does not predict complications, length of stay, and cost for patients older than 90 years with hip fractures. Orthopedics. 2019;42(1):e51–e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lagman C, Ugiliweneza B, Boakye M, Drazin D. Spine surgery outcomes in elderly patients versus general adult patients in the United States: a MarketScan analysis. World Neurosurg. 2017;103:780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malik AT, Jain N, Yu E, Kim J, Khan SN. Discharge to skilled-care or rehabilitation following elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion increases the risk of 30-day re-admissions and post-discharge complications. J Spine Surg. 2018;4(2):264–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Capua J, Somani S, Kim JS, et al. Predictors for patient discharge destination after elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976). 2017;42(20):1538–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz AD, Mancini N, Karukonda T, Cote M, Moss IL. Comparative and predictor analysis of 30-day readmission, reoperation, and morbidity in patients undergoing multilevel ACDF versus single and multilevel ACCF using the ACS-NSQIP dataset. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44(23):E1379–E1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph JR, Smith BW, Mummaneni PV, La Marca F, Park P. Postoperative dysphagia correlates with increased morbidity, mortality, and costs in anterior cervical fusion. J Clin Neurosci. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devin CJ, Chotai S, Parker SL, et al. A cost-utility analysis of lumbar decompression with and without fusion for degenerative spine disease in the elderly. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(Suppl 4):S116–S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reese JC, Karsy M, Twitchell S, Bisson EF. Analysis of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion healthcare costs via the value-driven outcomes tool. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(2):485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chotai S, Sivaganesan A, Parker SL, Sielatycki JA, McGirt MJ, Devin CJ. Drivers of variability in 90-day cost for elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion for cervical degenerative disease. Neurosurgery. 2018;83(5):898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veeravagu A, Connolly ID, Lamsam L, et al. Surgical outcomes of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: an analysis of a national, administrative, longitudinal database. Neurosurg Focus. 2016;40(6):E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-gsj-10.1177_2192568221989293 for Octogenarians Are Independently Associated With Extended LOS and Non-Routine Discharge After Elective ACDF for CSM by Aladine A. Elsamadicy, Andrew B. Koo, Benjamin C. Reeves, Isaac G. Freedman, Wyatt B. David, Jeff Ehresman, Zach Pennington, Maxwell Laurans, Luis Kolb and Daniel M. Sciubba in Global Spine Journal

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-2-gsj-10.1177_2192568221989293 for Octogenarians Are Independently Associated With Extended LOS and Non-Routine Discharge After Elective ACDF for CSM by Aladine A. Elsamadicy, Andrew B. Koo, Benjamin C. Reeves, Isaac G. Freedman, Wyatt B. David, Jeff Ehresman, Zach Pennington, Maxwell Laurans, Luis Kolb and Daniel M. Sciubba in Global Spine Journal