Abstract

Five immunodominant Treponema pallidum recombinant polypeptides (rTpN47, rTmpA, rTpN37, rTpN17, and rTpN15) were blotted onto strips, and 450 sera (200 from blood donors, 200 from syphilis patients, and 50 potentially cross-reactive) were tested to evaluate the diagnostic performance of recombinant Western blotting (recWB) in comparison with in-house whole-cell lysate antigen-based immunoblotting (wclWB) and T. pallidum hemagglutination (MHA-TP) for the laboratory diagnosis of syphilis. None of the serum specimens from blood donors or from potential cross-reactors gave a positive result when evaluated by recWB, wclWB, or MHA-TP. The evaluation of the immunoglobulin G immune response by recWB in sera from patients with different stages of syphilis showed that rTmpA was the most frequently identified antigen (95%), whereas only 41% of the specimens were reactive to rTpN37. The remaining recombinant polypeptides were recognized as follows: rTpN47, 92.5%; rTpN17, 89.5%; and rTpN15, 67.5%. The agreement between recWB and MHA-TP was 95.0% (100% with sera from patients with latent and late disease), and the concordance between wclWB and MHA-TP was 92.0%. The overall concordance between recWB and wclWB was 97.5% (100% with sera from patients with secondary and late syphilis and 94.6 and 98.6% with sera from patients with primary and latent syphilis, respectively). The overall sensitivity of recWB was 98.8% and the specificity was 97.1% with MHA-TP as the reference method. These values for sensitivity and specificity were slightly superior to those calculated for wclWB (sensitivity, 97.1%, and specificity, 96.1%). With wclWB as the standard test, the sensitivity and specificity of recWB were 98.9 and 99.3%, respectively. These findings suggest that the five recombinant polypeptides used in this study could be used as substitutes for the whole-cell lysate T. pallidum antigens and that this newly developed recWB test is a good, easy-to-use confirmatory method for the detection of syphilis antibodies in serum.

The laboratory diagnosis of syphilis is still a crucial point in the epidemiological and diagnostic evaluation of the disease (23, 32). Serologic screening has been performed over the past years by the use of Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and hemagglutination assay (MHA-TP), with the results confirmed by the immunofluorescence method (FTA-ABS) (23, 40). In recent years, however, several enzyme immunoassays based on either whole-cell lysate (8, 14, 24, 39) or recombinant (9, 12, 19, 48, 50) treponemal antigens have been developed for the serologic screening of syphilis sera, showing sensitivities and specificities similar to those of FTA-ABS and MHA-TP. All of the serologic tests for syphilis have been shown to possibly give false results when several different conditions are present: other spirochetal diseases, autoimmune disorders, or human immunodeficiency virus infection. Consequently, the use of a single method is considered insufficient to achieve the best diagnostic performance, and the quest for new, simple, reliable, and money-saving diagnostic methods continues.

The Western blot (WB) method has been used for the last 15 years to investigate the immune response to individual Treponema pallidum antigens in sera from experimentally infected animals (1, 16, 25, 26, 43, 46) and from humans with naturally occurring syphilis (4, 5, 6, 10, 17, 28, 30, 40, 47, 49). This method has been proposed as a possible alternative to either FTA-ABS or MHA-TP for the confirmation of the serological diagnosis of syphilis. At least nine T. pallidum polypeptides with apparent molecular masses of 15 (TpN15), 17 (TpN17), 33, 37 (TpN37), 39, 43, 45 (TmpA), 47 (TpN47), and 97 kDa have been identified as major immunogens (2, 11, 31, 33, 34, 45, 46). Among these polypeptides, at least five (TpN15, TpN17, TpN37, TmpA, and TpN47) proved to be of diagnostic relevance (4, 23, 28, 31, 32). While many different combinations of the above-mentioned immunogens in the recombinant form have been used in enzyme immunoassay methods (9, 12, 19, 48, 50), only a few preparations of recombinant T. pallidum polypeptides have been evaluated for the diagnosis of syphilis by WB (7, 38). The use of recombinant antigens could avoid the difficulties in purifying specific T. pallidum proteins due to the complex antigenic structure of this spirochete, and it has the potential to increase the specificity of serologic investigations. In fact, contamination with rabbit testicular tissue components may be partially responsible for unspecific results in syphilis serology. In addition, the production of recombinant antigens could allow the production and characterization of specific individual T. pallidum antigenic polypeptides in unlimited amounts, creating a consistent and cheap source of antigens.

In this study we set up a WB test (recombinant WB [recWB]) prepared with recombinant T. pallidum antigens rTpN47, rTmpA, rTpN17, rTpN15, and rTpN37. The results obtained by recWB were compared with those obtained using in-house whole-cell lysate antigen-based immunoblotting (wclWB) and MHA-TP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study groups.

Sera were obtained from three different groups of subjects. The first group of 200 specimens was obtained from blood donors (kindly provided by the Blutspendedienst des Bayerischen Roten Kreuzes, Munich, Germany). A second source of sera was a group of 200 patients attending the sexually transmitted disease outpatient clinic of the St. Orsola Hospital in Bologna, Italy, who were suffering from different stages of syphilis. The staging of the disease was done by following the clinical and laboratory criteria recently proposed by Norris and Larsen (32). In particular, 122 samples were from patients suffering from early syphilis (74 primary syphilis patients and 48 secondary syphilis patients), 74 samples were from patients with latent disease, and 4 samples were obtained from subjects with late (cardiovascular) syphilis. Among the 74 primary syphilis patients, 10 had been suffering from genital ulcers for less than 3 weeks. The third group of 50 serum samples was part of a previous study (29). The samples were obtained from patients who showed clinical and laboratory conditions well known to be potential causes of false-positive reactions in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis, and the patients had been referred to our laboratory in Bologna. Twenty-five sera were from patients suffering from other clinically and microbiologically confirmed spirochetal infections (18, 27, 35) (19 Lyme borreliosis patients and 6 leptospirosis patients), 15 sera were from pregnant women (3), and 10 sera were from subjects suffering from autoimmune disorders (13, 20) (antinuclear-antibody-positive sera).

Source of T. pallidum.

T. pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain) was originally obtained from the Statens Serum Institute (Copenhagen, Denmark) and maintained by passage in the testicles of adult male New Zealand White rabbits every 10 to 14 days. The animals were given antibiotic-free food and water ad libitum. Treponemes were extracted from the infected testicles and prepared for use as antigens as described elsewhere (29), after the animal had been euthanatized with thiopental (Pentothal).

Recombinant T. pallidum antigens.

Genomic DNA of T. pallidum strain Nichols was isolated using a method similar to that described by Langenberg and coworkers (22). DNA and DNA fragments were isolated as described by Sambrook et al. (37). Transformation, transfection, and the production of competent cells were carried out according to the method of Hanahan (15). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) were used as recommended by the manufacturer.

Five immunodominant (31) T. pallidum antigens, TpN47, TmpA, TpN37, TpN17, and TpN15 (GenBank accession numbers, M88769, M10931, M63142, M74825, and M30941, respectively), were expressed as full-length proteins in Escherichia coli. The genes were amplified from T. pallidum by PCR with specific primers based on the sequence information obtained from the GenBank database. Useful restriction enzyme sites were incorporated into these primers. All genes, with the sole exception of the TpN37 gene, were expressed without the sequences coding for the signal peptides. The cloned sequences were verified by sequence analysis.

The oligonucleotides were synthesized on a Gene Assembler (Pharmacia-LKB, Uppsala, Sweden) as described in the manufacturer's manual. All chemicals and supports (0.2 μmol) were obtained from and used as recommended by Pharmacia. Oligonucleotides were purified with NAP 10 columns (Pharmacia-LKB) as suggested by the manufacturer. The PCR was carried out using a commercially available PCR kit (Roche Diagnostics). Samples were denatured at 94°C for 2 min, annealed at 45°C for 2 min, and extended at 72°C for 4 min. The total number of cycles was 50. The reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide (0.5 mg/ml). DNA was extracted with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and precipitated with ethanol. Subsequently, the DNA was cleaved with suitable restriction enzymes. Fragments were cloned in a pUC8 plasmid vector, and recombinant antigens were expressed in E. coli JM 109.

SDS-PAGE.

The T. pallidum suspension was electrophoretically separated by using a Laemmli (21) buffer system and 12.5% polyacrylamide (16 cm long) separating gels, as previously reported (36). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) separation of the five recombinant T. pallidum antigens, purified from E. coli extracts by standard anion and cation ion-exchange chromatography, was carried out as described by Soutschek and coworkers (42), following the method of Laemmli (21).

WB.

The preparation of wclWB strips was done as previously described (35). Briefly, T. pallidum antigens, separated by SDS-PAGE as reported above, were blotted onto nitrocellulose sheets (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassell, Germany) by following the method of Towbin et al. (44), as reported elsewhere (28). The wclWB strips were incubated overnight in human sera, diluted 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Antigen-antibody complexes were detected with peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) and 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), as already described (28). As suggested by Byrne and coworkers (4), a wclWB test was considered positive when at least three of four T. pallidum immunogenic bands with apparent molecular masses of 47, 44.5, 17, and 15 kDa were present. A test was considered negative when no bands, or fewer than three of the above-mentioned T. pallidum antigens, were recognized.

To prepare recWB strips, recombinant T. pallidum polypeptides, separated by SDS-PAGE as described above, were transferred onto already numbered nitrocellulose sheets and blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5) containing 0.2% (vol/vol) skim milk powder. Serum incubation was carried out in a wash/dilution buffer (original preparation; Mikrogen, Martinsried, Germany) containing 1% (vol/vol) skim milk powder in a 1:200 dilution, for 1 h. The strips were then washed for 5 min three times with wash/dilution buffer, followed by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-human IgG antibody (Dako), diluted 1:1,000, for 45 min at room temperature. Again, the strips were washed for 5 min three times with wash/dilution buffer. Finally, the strips were stained with precipitated 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine solution containing H2O2 (original preparation; Mikrogen) for 2 to 5 min. At the end of the immunostaining, the strips were extensively washed with distilled water and the reaction pattern was recorded immediately.

To prevent bias, investigators evaluating the reactivities of human serum samples with all of the serologic methods used in this study were blinded to the group of sera being assessed.

MHA-TP and FTA-ABS.

The methods used were MHA-TP (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan) and FTA-ABS (bioMerieux, Marcy I'Etoile, France). These tests were performed in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturers. Titers of ≥80 and ≥20 were considered positive for MHA-TP and FTA-ABS testing, respectively.

RESULTS

Blood donor serum specimens.

A preliminary MHA-TP test showed a titer of <80 for all the samples belonging to the blood donor group, as expected. The sera from the blood donors showed the following results when tested using wclWB: seven samples identified only TpN47, five specimens were exclusively reactive to TmpA, and TpN37, TpN17, and TpN15 were individually reactive in six, one, and three cases, respectively. In addition, three serum samples were reactive to TpN47 and TpN37, and another sample identified both TpN47 and TpN15. The remaining 174 sera did not react at all. These findings demonstrate that all of these specimens failed to meet the above-mentioned positivity criteria for the evaluation of the wclWB strips.

The recWB was also applied to evaluate the blood donor specimens, and the findings were as follows: 169 sera were negative, 8 sera identified only the rTpN47, 6 sera were reactive to rTmpA alone, and 5, 3, and 4 sera reacted only to rTpN37, rTpN17, and rTpN15, respectively. In addition, two samples identified both rTpN47 and rTmpA, two samples were reactive with rTpN47 and rTpN37, and the last sample reacted to rTmpA and rTpN37. All the samples which reacted with at least one polypeptide, with either recWB or wclWB testing, were further evaluated by FTA-ABS IgG and found to be negative.

Serum specimens from syphilis patients.

Sera from syphilis patients reacted with the recWB antigens with differences in the reaction pattern depending on the stage of infection, as reported in Table 1. In particular, rTmpA was the most frequently recognized antigen in all stages of syphilis (100% in secondary and late disease and 87.8% and 98.6% in primary and latent syphilis, respectively), with 95.0% of sera reactive to it. Of the remaining recombinant T. pallidum antigens blotted onto the recWB strips, rTpN47 was identified by 92.5% of the specimens and rTpN37 was the least frequently reactive (82 samples of 200 studied [41.0%]). The recombinant antigens correspondent to the lower-molecular-mass polypeptides of T. pallidum, rTpN17 and rTpN15, were identified by 89.5 and 67.5% of the specimens, respectively. The most frequently reactive among the antigens in wclWB was TpN47, 99.5% of the specimens being reactive (all of the specimens from patients with secondary, latent, and late disease were reactive, whereas 98.6% of the sera from patients with primary syphilis recognized this antigen). The percentages of specimens reactive with the whole-cell T. pallidum antigens, other than TpN47, were as follows: TmpA, 95%; TpN37, 81%; TpN17, 89.0%; and TpN15, 77.5% (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

T. pallidum antigens recognized by IgG antibodies in sera obtained from patients suffering from syphilis

| T. pallidum antigena | No. (%) of positive sera at indicated stage of syphilis

|

Total positive (n = 200) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (n = 74) | Secondary (n = 48) | Latent (n = 74) | Late (n = 4) | ||

| rTpN47 | 63 (85.1) | 48 (100) | 70 (94.6) | 4 (100) | 185 (92.5) |

| wcTpN47 | 73 (98.6) | 48 (100) | 74 (100) | 4 (100) | 199 (99.5) |

| rTmpA | 65 (87.8) | 48 (100) | 73 (98.6) | 4 (100) | 190 (95) |

| wcTmpA | 67 (90.5) | 47 (97.9) | 72 (97.3) | 4 (100) | 190 (95) |

| rTpN37 | 26 (35.4) | 26 (54.1) | 26 (35.1) | 4 (100) | 82 (41) |

| wcTpN37 | 56 (75.6) | 41 (85.4) | 61 (82.4) | 4 (100) | 162 (81) |

| rTpN17 | 57 (77.0) | 48 (100) | 70 (94.6) | 4 (100) | 179 (89.5) |

| wcTpN17 | 54 (72.9) | 46 (95.8) | 74 (100) | 4 (100) | 178 (89) |

| rTpN15 | 50 (67.5) | 34 (70.8) | 49 (66.2) | 2 (50) | 135 (67.5) |

| wcTpN15 | 54 (72.9) | 38 (79.1) | 59 (79.7) | 4 (100) | 155 (77.5) |

Abbreviations: r, recombinant; wc, whole-cell lysate.

At present, there are no established and generally accepted criteria to evaluate a recombinant-polypeptide-based WB for syphilis. The analysis of the findings obtained by testing the blood donor specimens and the sera from syphilis patients by recWB showed that the recWB assay identified a positive serum specimen when at least three out of the five antigens were reactive, given that at least one of the two lower-molecular-mass polypeptides (rTpN17 and rTpN15) were included. A negative serum could be reactive with one, two, or no bands. Therefore, the criterion to assess the positivity of the recWB was that at least three out of the five antigens were identified, given that at least one of the two lower-molecular-mass polypeptides were included.

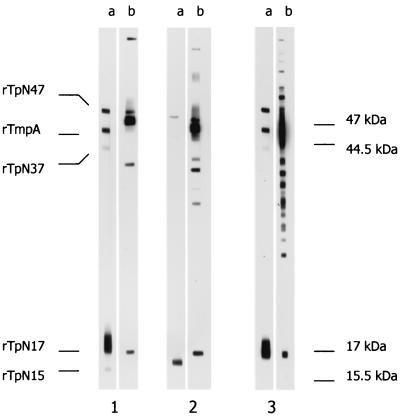

When used to define the immune response to T. pallidum antigens in sera obtained from syphilis patients, recWB showed a good diagnostic performance when compared to MHA-TP as well as to wclWB, as reported in Tables 2, 3, and 4. The overall sensitivity of recWB was 98.8% and the specificity was 97.1%, making the overall agreement between recWB and MHA-TP 95.0% (Table 2). (The concordance was 100% with sera from patients with late syphilis and 98.6% with sera from patients with latent syphilis; the agreement was lower with specimens obtained from patients with early disease, with a value of 97.9% for sera from patients with secondary syphilis. The agreement between recWB and MHA-TP was 80.0% when the duration of the genital ulcer was less than 3 weeks and 90.6% for sera obtained from patients with a duration of the chancre more than 21 days.) The comparison of recWB results to findings obtained with wclWB strips (Table 4) showed an overall sensitivity of 98.9%, a specificity of 99.3%, and a concordance of 97.5%, showing slight differences among the diverse groups of sera studied (80.0% when sera were from patients with a duration of primary syphilis of less than 21 days, 96.8% when the genital ulcers lasted for more than 3 weeks, 98.6% in latent disease, and 100% in the secondary and late stages). As expected, the concordance between findings obtained with MHA-TP and wclWB (Table 3) was 92.0%, as previously reported (28). The overall sensitivity and specificity of wclWB were 97.1 and 96.1%, respectively. The reactivity to rTpN37 proved to be essential to the increased sensitivity of recWB in 7 of the 200 sera from syphilis patients studied. In particular, three specimens from primary disease patients identified rTmpA, rTpN37, and rTpN17. Moreover, four samples from patients with latent syphilis were scored as positive due to the presence of reactivity to rTpN37. Namely, two samples identified rTpN47, rTpN37, and rTpN15; one serum sample was reactive to rTpN47, rTpN37, and rTpN17; and the last specimen reacted to rTmpA, rTpN37, and rTpN15. For an example of recWB reactivities compared with wclWB reactivities, see Fig. 1. Out of 200 serum specimens studied, 17 (8.5%) showed discrepancies when evaluated by the different methods. As expected, most of the discrepancies were observed for primary syphilis patients (Table 5).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of MHA-TP and recWB reactivities in sera obtained from patients with different stages of syphilis

| Syphilis stage of specimen source | No. (%) of specimens showing the following MHA-TP and recWB results, respectively:

|

% Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + and + | − and − | + and − | − and + | ||

| Primarya (n = 10) | 2 (20) | 6 (60) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 80 |

| Primaryb (n = 64) | 49 (76.6) | 9 (14.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (9.4) | 90.6 |

| Secondary (n = 48) | 46 (95.8) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 97.9 |

| Latent (n = 74) | 68 (91.9) | 5 (6.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 98.6 |

| Late (n = 4) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 |

Duration of genital ulcer was less than 3 weeks.

Duration of genital ulcer was more than 3 weeks.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of MHA-TP and wclWB reactivities in sera obtained from patients with different stages of syphilis

| Syphilis stage of specimen source | No. (%) of specimens showing the following MHA-TP and wclWB results, respectively:

|

% Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + and + | − and − | + and − | − and + | ||

| Primarya (n = 10) | 2 (20) | 6 (60) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 80 |

| Primaryb (n = 64) | 47 (73.4) | 7 (10.9) | 2 (3.1) | 8 (12.5) | 84.4 |

| Secondary (n = 48) | 46 (95.8) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 97.9 |

| Latent (n = 74) | 67 (90.5) | 4 (5.4) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.4) | 95.9 |

| Late (n = 4) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 |

Duration of genital ulcer was less than 3 weeks.

Duration of genital ulcer was more than 3 weeks.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of wclWB and recWB reactivities in sera obtained from patients with different stages of syphilis

| Syphilis stage of specimen source | No. (%) of specimens showing the following wclWB and recWB results, respectively:

|

% Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + and + | − and − | + and − | − and + | ||

| Primarya (n = 10) | 2 (20) | 6 (60) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 80 |

| Primaryb (n = 64) | 54 (84.3) | 8 (12.5) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 96.8 |

| Secondary (n = 48) | 47 (97.9) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 |

| Latent (n = 74) | 68 (91.9) | 5 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 98.6 |

| Late (n = 4) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 |

Duration of genital ulcer was less than 3 weeks.

Duration of genital ulcer was more than 3 weeks.

FIG. 1.

WB analysis of human sera using wclWB (lanes b) and recWB (lanes a). Serum no. 169 (lane 1, latent syphilis) was scored as positive by recWB and negative by wclWB, serum no. 183 (lane 2, latent syphilis) was positive by wclWB and negative by recWB, and sample no. 86 (lane 3, secondary syphilis) was positive by both recWB and wclWB. The apparent molecular masses of the individual T. pallidum proteins are shown on the right, and the positions of the five recombinant T. pallidum antigens are indicated on the left.

TABLE 5.

Discrepant results obtained in 17 of 200 syphilis serum specimens

| Sample no. | Syphilis stagea | Result

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| recWB | wclWB | MHA-TPb | FTA-ABSb | ||

| 15 | Primary | Positive | Positive | Negc | 40 |

| 28 | Primary | Positive | Positive | Neg | 20 |

| 34 | Primary | Positive | Positive | Neg | 20 |

| 39 | Primary | Positive | Positive | Neg | 40 |

| 41 | Primary | Positive | Positive | Neg | 80 |

| 45 | Primary | Positive | Positive | Neg | 40 |

| 53 | Primary | Positive | Positive | Neg | 40 |

| 61 | Primary | Negative | Positive | Neg | 20 |

| 68 | Primary | Negative | Positive | Neg | 40 |

| 69 | Primary | Positive | Negative | 80 | Neg |

| 71 | Primary | Positive | Negative | 160 | Neg |

| 73 | Primary | Negative | Negative | 80 | Neg |

| 85 | Secondary | Positive | Positive | Neg | 160 |

| 102 | Secondary | Negative | Negative | 80 | Neg |

| 157 | Latent | Negative | Negative | 160 | 40 |

| 169 | Latent | Positive | Negative | 160 | 80 |

| 183 | Latent | Negative | Positive | 80 | Neg |

All samples belonging to the primary syphilis group were from patients with a genital ulcer lasting more than 21 days with the exception of sample no. 53, 61, and 73, which were obtained from subjects with a chancre lasting less than 3 weeks.

Results are expressed as titers.

Neg, titers of less than 80 (MHA-TP) or 20 (FTA-ABS).

Potential cross-reactors.

The MHA-TP results obtained with the potential cross-reactor specimens were negative in 49 of the 50 cases evaluated. Only one serum sample obtained from a patient suffering from Lyme borreliosis showed a titer of 80, but this positive finding was not confirmed by wclWB and recWB evaluation.

When applied to the 50 serum specimens from patients suffering from clinical conditions well known as sources of potential cross-reactions in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis, the diagnostic performance of recWB was comparable to that of wclWB. No positive samples were identified using the recombinant-antigen-based immunoblotting techniques. No reaction was found against rTpN17 and rTpN15. Similar results were obtained with wclWB.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of syphilis is based upon clinical symptoms, laboratory examination of skin or mucous lesion material, and serology (41). Since the lesion material is available for examination only during the early stage of disease, the main laboratory diagnostic tool for stages other than primary syphilis is the detection of a specific antibody response to T. pallidum (23, 32).

The WB technique based on whole-T. pallidum-cell lysate has been widely used in past years (5, 6, 10, 12, 17, 28, 30, 49), and it has been shown to be a reliable confirmatory test (4). Few data are available on the use of recombinant-antigen-based immunoblotting in the diagnosis of syphilis. Recently, a paper by Sato and coworkers (38) appeared describing the immune reactivity of three glutathione S-transferase fusion recombinant antigens (rTp47, rTp17, and rTp15), whereas Ebel et al. (7) reported on the use of a single multiparametric line immunoassay, containing separated recombinant forms of four T. pallidum antigens, TpN47, TmpA, TpN17, and TpN15, for the confirmatory diagnosis of syphilis.

Our results indicated that the WB techniques could be performed by using recombinant T. pallidum antigens instead of spirochetal whole-cell lysate, without any decrease in the overall diagnostic performance of the method. Using MHA-TP as the reference treponemal test, the concordance between recWB and the hemagglutination method was 95.0% considering all of the sera from syphilis patients studied. As expected, the later the sera were studied in the course of infection, the higher the agreement was between recWB and MHA-TP. The results also showed that the concordance between wclWB and MHA-TP was 92.0%. In addition, the agreement between the two WB methods was 97.5%. The high concordance between the recWB and wclWB techniques strongly suggests that recombinant antigens could act as substitutes for the whole-cell-lysate T. pallidum polypeptides without any loss of sensitivity when the recWB is applied to serum specimens drawn from syphilis patients. In addition, since no positive results were found when a large number of potentially cross-reactive sera were studied by using wclWB and recWB, our findings proved that both methods are highly specific. Previous results are therefore strongly confirmed and extended, thus allowing the recWB technique to enter the pool of confirmatory methods for syphilis. The use of the readily available recombinant antigens, in addition to avoiding the well-known cross-reactivities with other spirochetal antigens and contaminating residues from rabbit testies, would overcome the problem of growing T. pallidum in animals (23, 31) and consequently simplify the procedure of preparing WB strips with treponemal antigens, permitting a wider use of this technique in the laboratory confirmatory diagnosis of syphilis. In addition, recWB strips contain few immunodominant antigens, allowing easier reading and interpretation of the results. Further improvement of this method could be made in the future by introducing a score reading system based on the comparative analysis between the intensity and reaction pattern shown by a reference serum, which could act as a cutoff control serum, and the bands identified by the specimens studied, which would make the interpretation of the results easier and simpler. Such improvements would probably allow a wider use of the recWB method in the diagnosis of T. pallidum infection, enlarging the number of available confirmatory tests for syphilis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker-Zander S A, Fohn M J, Lukehart S A. Development of cellular immunity to individual soluble antigen of Treponema pallidum during experimental syphilis. J Immunol. 1988;141:4363–4369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco D R, Reimann K, Skare J, Champion C I, Foley D, Exner M M, Hancock R E W, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Isolation of the outer membranes from Treponema pallidum and Treponema vincentii. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6088–6099. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6088-6099.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan C S, Haserick J R. FTA-ABS test in pregnancy: a probable false-positive reaction. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:333–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne R E, Laska S, Bell M, Larson D, Phillips J, Todd J. Evaluation of a Treponema pallidum Western immunoblot assay as a confirmatory test for syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:115–122. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.1.115-122.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dettori G, Grillo R, Mora G, Cavalli A, Alinovi A, Chezzi C, Sanna A. Evaluation of Western immunoblotting technique in the serological diagnosis of human syphilitic infections. Eur J Epidemiol. 1989;5:22–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00145040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobson S R, Taber L H, Baughn R E. Recognition of Treponema pallidum antigens by IgM and IgG antibodies in congenitally infected newborns and their mothers. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:903–910. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebel A, Vanneste L, Cardinaels M, Sablon E, Samson I, De Bosschere K, Hulstaert F, Zrein M. Validation of the INNO-LIA syphilis kit as a confirmatory assay for Treponema pallidum antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:215–219. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.215-219.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farshy C E, Hunter E F, Helsel L O, Larsen S A. Four-step enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of Treponema pallidum antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:387–389. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.3.387-389.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimura K, Ise N, Ueno E, Hori T, Fujii N, Okada M. Reactivity of recombinant Treponema pallidum (r-Tp) antigens with anti-Tp antibodies in human syphilitic sera evaluated by ELISA. J Clin Lab Anal. 1997;11:315–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1997)11:6<315::AID-JCLA1>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George R W, Pope V, Larsen S A. Use of the Western blot for the diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Immunol Newsl. 1991;8:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 11.George R W, Pope V, Fears M, Morril B, Larsen S A. An analysis of the value of some antigen-antibody interactions used as diagnostic indicators in a treponemal Western blot (TWB) test for syphilis. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1998;50:27–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber A, Krell S, Morenz J. Recombinant Treponema pallidum antigens in syphilis serology. Immunobiology. 1997;196:535–549. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(97)80070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibowski M, Neumann E. Non-specific positive test results to syphilis in dermatological diseases. Br J Vener Dis. 1980;56:17–19. doi: 10.1136/sti.56.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halling V W, Jones M F, Bestrom J E, Wold A D, Rosenblatt J E, Smith T F, Cockerill F R., III Clinical comparison of the Treponema pallidum CAPTIA syphilis-G enzyme immunoassay with the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption immunoglobulin G assay for syphilis testing. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3233–3234. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3233-3234.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanff P A, Bishop N H, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Humoral immune response in experimental syphilis to polypeptides of Treponema pallidum. J Immunol. 1983;131:1973–1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hensel U, Wellensiek H-J, Bhakdi S. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis immunoblotting as a serological tool in the diagnosis of syphilitic infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:82–87. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.1.82-87.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter E F, Russell H, Farshy C E, Sampson J S, Larsen S A. Evaluation of sera from patients with Lyme disease in the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test for syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13:233–236. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ijsselmuiden O E, Schouls L M, Stolz E, Aelbers G N M, Agterberg C M, Top J, van Embden J D A. Sensitivity and specificity of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the recombinant DNA-derived Treponema pallidum protein TmpA for serodiagnosis of syphilis and the potential use of TmpA for assessing the effect of antibiotic therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:152–157. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.1.152-157.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraus S J, Haserick J R, Lantz M. Fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test reactions in lupus erythematosus. Atypical beading pattern and probable false-positive reactions. N Engl J Med. 1970;333:1247–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197006042822303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langenberg W, Rauws E A J, Widjojokusumo A, Tytgat G N J, Zanen H C. Identification of Campylobacter pyloridis isolates by restriction endonuclease DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:414–417. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.3.414-417.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen S A, Steiner B M, Rudolph A H. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1–21. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefevre J-C, Bertrand M-A, Bauriaud R. Evaluation of the Captia-enzyme immunoassays for detection of immunoglobulins G and M to Treponema pallidum in syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1704–1707. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.8.1704-1707.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukehart S A, Baker-Zander S A, Gubish E. Identification of Treponema pallidum antigens: comparison with non-pathogenic treponemes. J Immunol. 1982;129:833–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukehart S A, Baker-Zander S A, Sell S. Characterization of the humoral immune response of the rabbit to antigens of Treponema pallidum after experimental infection and therapy. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13:9–15. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luther B, Moskophidis M. Antigenic cross-reactivity between Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia recurrentis, Treponema pallidum, and Treponema phagedenis. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1990;274:214–226. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marangoni A, Sambri V, Olmo A, D'Antuono A, Negosanti M, Cevenini R. IgG Western blot as a confirmatory test in early syphilis. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1999;289:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(99)80095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marangoni A, Sambri V, Storni E, D'Antuono A, Negosanti M, Cevenini R. Treponema pallidum surface immunofluorescence assay for serologic diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:417–421. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.3.417-421.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer M P, Eddy T, Baughn R E. Analysis of Western blotting (immunoblotting) technique in diagnosis of congenital syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:629–633. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.629-633.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norris S J the Treponema pallidum Polypeptide Research Group. Polypeptides of Treponema pallidum: progress toward understanding their structural, functional, and immunologic roles. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:750–779. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.750-779.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norris S J, Larsen S A. Treponema and other host-associated spirochetes. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 636–651. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radolf J D, Robinson E J, Bourell K W, Akins D R, Porcella S F, Weigel L M, Jones J D, Norgard M V. Characterization of outer membranes isolated from Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4244–4252. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4244-4252.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodgers G C, Laird W J, Coates S R, Mack D H, Huston M, Sninsky J J. Serological characterization and gene localization of an Escherichia coli-expressed 37-kilodalton Treponema pallidum antigen. Infect Immun. 1986;53:16–25. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.16-25.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambri V, Moroni A, Massaria F, Brocchi E, De Simone F, Cevenini R. Immunological characterization of a low molecular mass polypeptidic antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol Immunol. 1991;3:345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambri V, Marangoni A, Olmo A, Storni E, Montagnani M, Fabbi M, Cevenini R. Specific antibodies reactive with the 22-kilodalton major outer surface protein of Borrelia anserina Ni-NL protect chicks from infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2633–2637. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2633-2637.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato N S, Hirata M H, Hirata R D, Zerbini L C, Silveira E P, de Melo C S, Ueda M. Analysis of Treponema pallidum recombinant antigens for diagnosis of syphilis by Western blotting technique. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1999;41:115–118. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651999000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt B L, Edjlalipour M, Luger A. Comparative evaluation of nine different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for determination of antibodies against Treponema pallidum in patients with primary syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1279–1282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1279-1282.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmitz J L, Gertis K S, Mauney C, Stamm L V, Folds J D. Laboratory diagnosis of congenital syphilis by immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgA immunoblotting. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1:32–37. doi: 10.1128/cdli.1.1.32-37.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh A E, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187–209. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soutschek E, Höflacher B, Motz M. Purification of a recombinantly produced transmembrane protein (gp41) of HIV 1. J Chromatogr. 1990;521:267–277. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(90)85051-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strugnell R A, Williams W F, Drummond L, Pedersen J S, Toh B H, Faine S. Development of increased serum immunoblot reactivity against a 45,000-dalton polypeptide of Treponema pallidum (Nichols) correlates with establishment of chancre immunity in syphilitic rabbits. Infect Immun. 1986;51:957–960. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.3.957-960.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wicher K, Jakubowski A, Wicher V. Humoral response in Treponema pallidum-infected guinea pigs. I. Antibody specificity. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987;69:263–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wicher K, Wos S M, Wicher V. Kinetics of antibody response to polypeptides of pathogenic and nonpathogenic treponemes in experimental syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13:251–257. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wicher V, Zabek J, Wicher K. Pathogen-specific humoral response in Treponema pallidum-infected humans, rabbits, and guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:830–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young H, Moyes A, Seagar L, McMillan A. Novel recombinant-antigen enzyme immunoassay for serological diagnosis of syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:913–917. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.913-917.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young H, Walker P J, Merry D, Mifsud A. A preliminary evaluation of a prototype Western blot confirmatory test for syphilis. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:409–414. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zrein M, Maure I, Boursier F, Soufflet L. Recombinant antigen-based enzyme immunoassay for screening of Treponema pallidum antibodies in blood bank routine. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:525–527. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.525-527.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]