Abstract

Background:

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is a common complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) and has the potential to induce shunt infection. Especially in infants and children, these are serious complications. DuraGen is a collagen matrix dural substitute used to reduce the risk of CSF leakage in various neurosurgeries. We report our VPS procedure with DuraGen for preventing postoperative CSF leakage in patients aged <1 year.

Methods:

We used DuraGen to prevent postoperative CSF leakage in six VPS surgeries. Antibiotic-impregnated shunt catheters and programmable valves with anti-siphon devices were also used in all cases. DuraGen was placed inside and atop the burr hole. All cases had an initial shunt pressure of 5 cmH2O. Fibrin glue was not used.

Results:

The patients underwent follow-up for a year after VPS surgery. There was no postoperative subcutaneous CSF collection or leakage after all six VPS surgeries. Furthermore, no postoperative shunt infections or DuraGen-induced adverse events were noted.

Conclusion:

We speculate that DuraGen has a preventive effect on postoperative CSF leakage in VPS cases aged <1 year.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid leakage, Collagen matrix, Hydrocephalus, Pediatric neurosurgery, Shunt infection, Ventriculoperitoneal shunt

INTRODUCTION

A ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) is a common procedure for hydrocephalus in newborns and infants. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage is a common complication of VPS, occurring in about 7% of patients who have undergone VPS.[7,9] There are several proposed methods for preventing CSF leakage, including low-pressure or programmable valves, minimal dural incision, frontal burr hole, catheter placement in a region containing the largest cerebral portion, and postoperative positioning with the head raised.[4,15]

Shunt infection is a serious complication that could lead to severe morbidity and mortality;[5,6,14,20] moreover, it has economic effects.[3,17,19] The shunt infection rate after VPS surgery is 4.1–20.5%.[1] CSF leakage is among the risk factors for shunt infection.[7,9] Specifically, CSF leakage at the surgical site increases the risk of infection by 19.16-fold[9] up to 27-fold.[7] In addition, CSF accumulation along the shunt tract is associated with a significant increase in the risk of infection.[4] Young age is another reported risk factor for shunt infection.[9,11,16,18] Therefore, it is important to prevent CSF leakage to reduce postoperative complications.

The collagen matrix acts as a scaffold on which host fibroblasts lay down new collagen, which promotes fibrin clot formation, with full reabsorption with the dura healing and integration into the endogenous dura mater.[8,12] Collagen matrix dural substitutes are used to reduce the risk of CSF leakage in various neurosurgeries. DuraGen (Integra Lifesciences, Plainsboro, NJ, USA) is a sutureless dural substitute graft composed of purified type I collagen extracted from bovine Achilles tendons.

Herein, we report our VPS procedure with DuraGen for preventing postoperative CSF leakage in patients aged <1 year.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

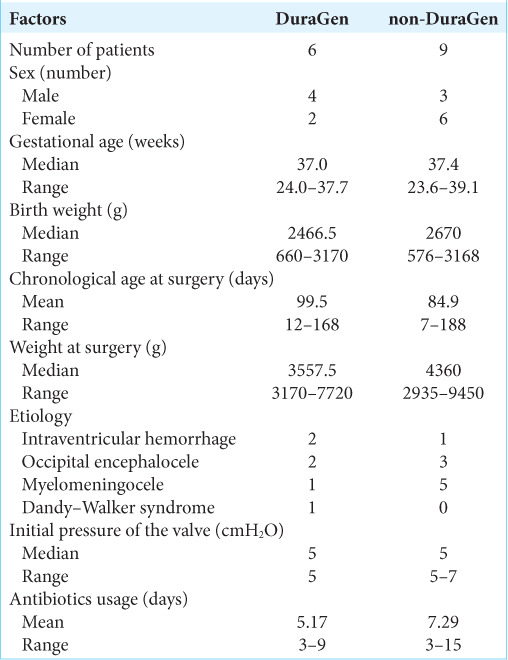

We used DuraGen in all VPS surgeries in patients aged <1 year at Kagoshima City Hospital between June 2020 and December 2020. We performed six VPS surgeries with DuraGen (including one revision VPS surgery) in this period. Nine patients aged <1 year who underwent VPS surgery with antibiotic-impregnated shunt catheters (AISCs): Bactiseal (Codman, Johnson and Johnson, Raynham, Massachusetts, USA) and programmable valves: proGAV 2.0 (Miethke, Aesculap, Potsdam, Tuttlingen, Germany) or Hakim Medos (Codman, Johnson and Johnson, Raynham, Massachusetts, USA) without DuraGen (including two revision VPS surgeries) before June 2020 were considered the control group (non-DuraGen). Table 1 shows patients’ characteristics. All DuraGen cases were treated using ventricular and AISCs: Bactiseal (Codman, Johnson and Johnson, Raynham, Massachusetts, USA), which were connected to a programmable valve with anti-siphon devices: proGAV 2.0 (Miethke, Aesculap, Potsdam, Tuttlingen, Germany). Furthermore, all cases with DuraGen had an initial shunt pressure of 5 cmH2O.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics of the DuraGen and non-DuraGen groups.

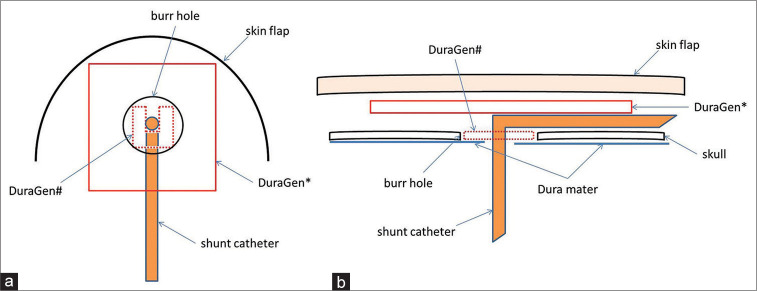

Figure 1 shows how to use DuraGen in our VPS procedure. First, a semicircular skin incision was made, and the skin flap was detached under epicranial aponeurosis. The pedicle periosteum was peeled to make a 5–7 mm diameter burr hole. Next, a ventricular tube was placed in the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle. A 5 mm2 notched DuraGen# was placed on the dura mater in the burr hole and enclosed the ventricular tube [Figure 1a and b#]. If possible, the DuraGen# and burr hole were then covered with the peeled pedicle periosteum. In addition, the tube and burr hole were covered with 1.5 cm2 DuraGen* [Figure 1a and b*]. Finally, we performed normal wound closure. Fibrin glue was not used in all cases.

Figure 1:

Place a 5 mm2 notched DuraGen in the burr hole and enclose the ventricular tube (a # and b #). Cover with 1.5 cm2 DuraGen over the tube and burr hole (a *and b *). (a) Overlooking view. (b) Sectional view.

RESULTS

All patients underwent follow-up for a year after VPS surgery. There was no consistent postoperative subcutaneous CSF collection or leakage (zero of six surgeries) in the DuraGen group; in contrast, six cases of CSF leakage (including subcutaneous CSF collection) were observed in the non-DuraGen group. There were also no cases and two cases of postoperative shunt infection in the DuraGen and non-DuraGen groups, respectively. Moreover, two cases of shunt infection with CSF leakage that required revision surgery were noted in the non-DuraGen group, while one case of ventral tube obstruction without infection that required revision surgery was reported in the DuraGen group. In addition, DuraGen-induced adverse events were not observed in all surgeries.

DISCUSSION

Our previous nine patients with VPS aged <1 year using AISCs and programmable valves without DuraGen had six subcutaneous CSF collections or CSF leakage and two infections. It was suggested that DuraGen has a preventive effect on CSF leakage in patients <1 year.

Collagen matrix is commonly used in dural closure and plasty in various neurosurgeries. Graft encapsulation, neo-membrane formation, delayed bleeding, and foreign body reaction have not been reported in dural plasty with collagen matrix dural substitutes.[2,12] DuraGen is almost noninfectious, nonantigenic, and nonimmunogenic, with all substances, including viruses, except for collagen removal. Collagen matrices have comparable infection rates as other dural closure techniques (6.1 vs. 5.7% [P = 0.67]).[18] There were no DuraGen-related adverse events; in addition, collagen matrices are considered highly safe for newborns and infants.

DuraGen is a sutureless dural substitute graft. Collagen matrix dural substitutes initially adhere to the dura through surface tension.[12] Neulen et al.[13] examined DuraGen adhesion and water tightness in dural plasty using pigs. They observed CSF leakage at 5.5 ± 4.6 mmHg in dural plasty with DuraGen, with adjustment of the intracranial pressure using the head down and Valsalva maneuver. All our cases had an initial shunt pressure of 5 cmH2O (= 3.68 mmHg). Using a CSF diversionary procedure, postoperative CSF leakage disappeared in very extensive posterior fossa surgery and Chiari malformation surgery associated with temporary or permanent hydrocephalus, in which dural plasty was performed using the collagen matrix.[12] Adhesion through surface tension could be maintained until chemical adhesion by fibrin is obtained. In addition, DuraGen, which is placed on the burr hole and adheres to the surrounding tissue around the burr hole through surface tension, is pressed by the sewn-closed skin flap to yield a strong sealing effect to prevent CSF leakage from the burr hole. In addition, DuraGen could reduce the subcutaneous dead space for CSF collection. Since the collagen sponge absorbs fluid without increasing its volume, there is a low risk of necrosis of the skin flap due to the strong pressure on it. First, DuraGen has a dural closure effect by promoting fibroblast infiltration and fibrin clot formation.[8,12] Narotam et al.[12] reported that 2–10 days after surgery, the collagen sponge was already adherent to the dura; moreover, fibrin, which is derived from blood in the surgical area, had formed a good seal against the CSF at the edges. DuraGen is thought to tightly adhere to the dura immediately after surgery to prevent CSF leakage. Soon after surgery, DuraGen is presumed to tightly adhere to the subcutaneous tissue, accelerating subcutaneous wound healing.[10] We speculated that these processes prevented subcutaneous CSF collection and CSF leakage on our VPS procedure.

Despite these findings, a limitation of this nonrandomized controlled study was its small sample size. DuraGen was used in our VPS procedure for the 1st time in June 2020 with the aim of preventing CSF leakage, as shown in Figure 1. Given that there was no CSF leakage in the first case, DuraGen was used in all five consecutive VPS procedures, all of which reported no CSF leakage. Therefore, we compared the incidence of CSF leakage when performing VPS procedures with and without (before June 2020) DuraGen. To clarify the preventive effect of DuraGen on CSF leakage, further trials are necessary.

CONCLUSION

Our findings suggest that DuraGen can be safely used in neonates and infants, and it has a preventive effect on CSF leakage.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Sato M, Oyoshi T, Iwamoto H, Tanoue N, Komasaku S, Higa N, et al. The collagen matrix dural substitute graft prevents postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage after ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery in patients aged <1 year. Surg Neurol Int 2022;13:461.

Contributor Information

Masanori Sato, Email: masanori-sato@umin.ac.jp.

Tatsuki Oyoshi, Email: tatsuki@m2.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Hirofumi Iwamoto, Email: punadiver@gmail.com.

Natsuko Tanoue, Email: natsu.tano3@gmail.com.

Soichiro Komasaku, Email: komasaku0812@yahoo.co.jp.

Nayuta Higa, Email: nayuhiga@gmail.com.

Hiroshi Hosoyama, Email: hiroshitok@nag.bbiq.jp.

Hiroshi Tokimura, Email: hiroshitok@nag.bbiq.jp.

Satoshi Ibara, Email: ibarasatoshi8@gmail.com.

Ryosuke Hanaya, Email: hanaya@m2.kufm.kagoshima-u.ac.jp.

Koji Yoshimoto, Email: kyoshimo@ns.med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams DJ, Rajnik M. Microbiology and treatment of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections in children. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16:427. doi: 10.1007/s11908-014-0427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Çetin B, Şengül G, Tüzün Y, Gündoğdu C, Kadıoğlu HH, Aydın İH. Suitability of collagen matrix as a dural graft in the repair of experimental posterior fossa dura mater defects. Turk Neurosurg. 2006;16:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1422–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis SE, Levy ML, McComb JG, Masri-Lavine L. Does age or other factors influence the incidence of ventriculoperitoneal shunt infections? Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;30:253–7. doi: 10.1159/000028806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forward KR, Fewer HD, Stiver HG. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections. A review of 35 infections in 32 patients. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:389–94. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.3.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrop JS, Sharan AD, Ratliff J, Prasad S, Jabbour P, Evans JJ, et al. Impact of a standardized protocol and antibiotic-impregnated catheters on ventriculostomy infection rates in cerebrovascular patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:187–91. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000370247.11479.B6. discussion 191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeelani NU, Kulkarni AV, Desilva P, Thompson DN, Hayward RD. Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid wound leakage as a predictor of shunt infection: A prospective analysis of 205 cases. Clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:166–9. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.PEDS08458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knopp U, Christmann F, Reusche E, Sepehrnia A. A new collagen biomatrix of equine origin versus a cadaveric dura graft for the repair of dural defects--a comparative animal experimental study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:877–87. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulkarni AV, Drake JM, Lamberti-Pasculli M. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection: A prospective study of risk factors. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:195–201. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.2.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lullove E. Acellular fetal bovine dermal matrix in the treatment of nonhealing wounds in patients with complex comorbidities. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2012;102:233–9. doi: 10.7547/1020233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGirt MJ, Leveque JC, Wellons JC, 3rd, Villavicencio AT, Hopkins JS, Fuchs HE, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt survival and etiology of failures: A seven-year institutional experience. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002;36:248–55. doi: 10.1159/000058428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narotam PK, Van Dellen JR, Bhoola KD. A clinicopathological study of collagen sponge as a dural graft in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:406–12. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.3.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neulen A, Gutenberg A, Takács I, Wéber G, Wegmann J, Schulz-Schaeffer W, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and biocompatibility of a novel semisynthetic collagen matrix as a dural on lay graft in a large animal model. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:2241–50. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raffa G, Marseglia L, Gitto E, Germanò A. Antibiotic-impregnated catheters reduce ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection rate in high-risk newborns and infants. Childs Nerv Syst. 2015;31:1129–38. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rohde V, Weinzierl M, Mayfrank L, Gilsbach JM. Postshunt insertion CSF leaks in infants treated by an adjustable valve opening pressure reduction. Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18:702–4. doi: 10.1007/s00381-002-0620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rotim K, Miklic P, Paladino J, Melada A, Marcikic M, Scap M. Reducing the incidence of infection in pediatric cerebrospinal fluid shunt operations. Childs Nerv Syst. 1997;13:584–7. doi: 10.1007/s003810050144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon CN, Simon TD, Reed GT, Franklin FA, Kirby RS, Kilgore ML, et al. The economic impact of ventriculoperitoneal shunt failure. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8:593–9. doi: 10.3171/2011.9.PEDS11192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon TD, Hall M, Riva-Cambrin J, Albert JE, Jeffries HE, Lafleur B, et al. Infection rates following initial cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement across pediatric hospitals in the United States. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:156–65. doi: 10.3171/2009.3.PEDS08215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon TD, Riva-Cambrin J, Srivastava R, Bratton SL, Dean JM, Kestle JR, et al. Hospital care for children with hydrocephalus in the United States: Utilization, charges, comorbidities, and deaths. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:131–7. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/1/2/131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang KW, Chang WN, Shih TY, Huang CR, Tsai NW, Chang CS, et al. Infection of cerebrospinal fluid shunts: Causative pathogens, clinical features, and outcomes. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57:44–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]