Abstract

Background:

Our goal was to identify racial and ethnic disparities in health outcome and care measures in Wisconsin.

Methods:

We used electronic health record data from 25 health systems submitting to the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality to identify disparities in measures including vaccinations, screenings, risk factors for chronic disease, and chronic disease management.

Results:

American Indian/Alaska Native and Black populations experienced substantial disparities across multiple measures. Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino and White populations experienced substantial disparities for two measures each.

Discussion:

Reducing health disparities is a statewide imperative. Root causes of health disparities such as systemic racism and socioeconomic factors should be addressed for groups experiencing multiple disparities, with focused efforts on selected measures when indicated.

Background

Although Wisconsin ranks highly in overall healthcare quality, the state performs poorly with respect to health disparities. In a national report, Wisconsin performed worse than the U.S. average on 22 out of 27 measures of disparities in care for Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black populations relative to White populations.1 The Health of Wisconsin Report Card, published by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute in 2016, gave the state a grade of “D” for overall health disparities.2 The 2019 County Health Rankings Report for Wisconsin found that American Indian/Alaska Native and Black populations had substantially worse health outcomes than the Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and White populations.3 This report adds detailed information on disparities in specific health outcome and care measures that distinguish these populations.

To eliminate health disparities in Wisconsin, it is critical to understand where disparities exist. Measuring disparities in health outcomes and care allows for benchmarking of current performance and monitoring changes over time.4 Measurement also allows stakeholders to prioritize efforts and develop and implement programs for the populations that are most impacted by disparities. Regular monitoring of disparity measures promotes transparency and accountability, and helps to ensure that efforts continue to eliminate these gaps.

The Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ) is a regional health improvement collaborative that publicly reports and brings meaning to health outcome and care measures in Wisconsin. WCHQ members include 35 health systems that represent more than 65 percent of Wisconsin’s primary care providers. Member organizations voluntarily submit electronic health record (EHR) data to WCHQ for public reporting of quality measures on their website (https://reports.wchq.org/).

With funding from the Wisconsin Partnership Program, WCHQ members and the University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program leveraged the existing WCHQ data to develop the 2019 Wisconsin Health Disparities Report (https://www.wchq.org/disparities.php). Herein we share highlights from this report to identify where disparities in health outcomes and care exist in Wisconsin by race/ethnicity and to help inform and accelerate programs that are working to eliminate disparities.

Methods

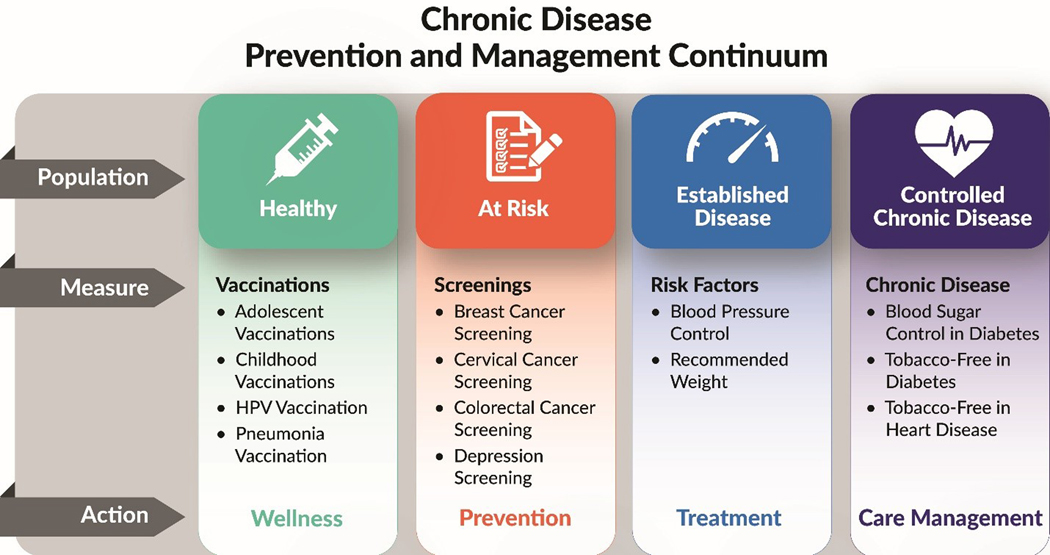

The WCHQ health outcome and care measures are organized using a model (Figure 1) adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Care Continuum.5 The model shows population health at four stages: healthy, at-risk, established disease, and controlled chronic disease. The model orients readers to actions to prevent populations from progressing from one health state to the next. The health outcome and care measures include vaccinations, screenings, risk factors for chronic disease, and chronic disease management.

Figure 1:

Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality Measures within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Disease Prevention and Management Continuum

To ensure high quality race and ethnicity data, we completed an assessment of data completeness and quality in the WCHQ data repository. WCHQ worked directly with members to improve mapping and submission of race and ethnicity data in the EHR as needed. We used race and ethnicity categories as defined by the CDC, including American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic/Latino, and White.6

Data from the WCHQ members were validated, comparing denominators and performance rates with their publicly reported measure results. Some member-level data were excluded from analysis due to incompleteness or quality issues. Statewide EHR data for nine health outcome and care measures from January 1, 2018 – December 31, 2018 were stratified by race/ethnicity. Substantial disparities were defined as a 10% or greater difference between a population group and the highest performing population group for the measure. For all measures, higher performance is better (e.g. higher screening rates, a higher percentage of people with their blood pressure under control). Additional details on the methodology and measures as well as results for all publicly reported measures are available in the report appendix on HIPxChange (https://www.hipxchange.org/WCHQDisparities).

Results

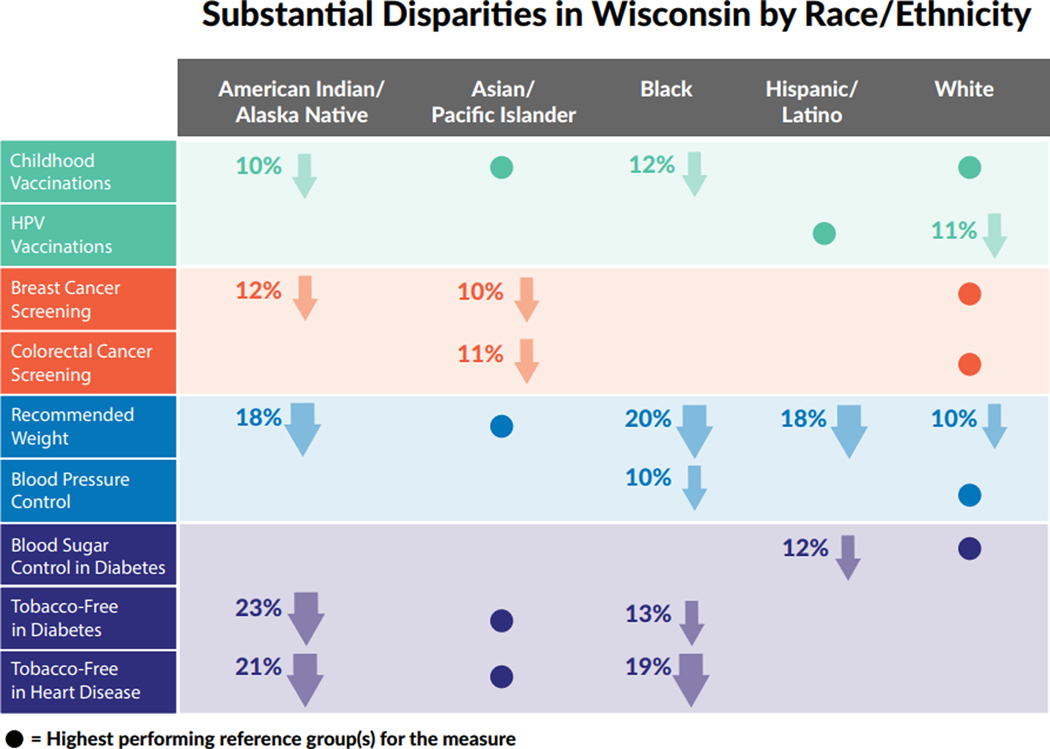

Substantial disparities in health outcomes and care by race/ethnicity were found for each race/ethnicity group (Table 1). Table 1 shows the percent achievement of each measure by racial/ethnic group. American Indian/Alaska Native and Black populations experienced substantial disparities across multiple measures. Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino and White populations experienced substantial disparities for two measures each.

Table 1:

Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality Measure Results by Race/Ethnicity

| Measure Name | American Indian/Alaska Native | Asian/Pacific Islander | Black | Hispanic/ Latino |

White |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood Vaccinations | 73%* | 83% | 71%* | 81% | 83% |

| N=206 | N=1,726 | N=2,532 | N=3,628 | N=30,312 | |

| HPV Vaccinations | 65% | 64% | 64% | 68% | 57%* |

| N=127 | N=706 | N=1,455 | N=2,210 | N=22,495 | |

| Breast Cancer Screening | 67%* | 69%* | 75% | 74% | 79% |

| N=1,467 | N=6,594 | N=26,330 | N=12,709 | N=522,959 | |

| Colorectal Cancer Screening | 71% | 68%* | 77% | 72% | 79% |

| N=2,584 | N=11,944 | N=46,301 | N=25,347 | N=1,030,825 | |

| Recommended Weight | 21%* | 39% | 19%* | 21%* | 29%* |

| N=4,831 | N=26,839 | N=87,087 | N=58,309 | N=1,602,200 | |

| Blood Pressure Control | 82% | 82% | 74%* | 80% | 84% |

| N=1,496 | N=6,402 | N=39,125 | N=14,592 | N=554,193 | |

| Blood Sugar Control in Diabetes | 65% | 69% | 66% | 62%* | 74% |

| N=1,050 | N=4,025 | N=15,362 | N=9,402 | N=181,631 | |

| Tobacco-Free in Diabetes | 69%* | 92% | 79%* | 87% | 86% |

| N=956 | N=3,775 | N=15,159 | N=8,922 | N=164,264 | |

| Tobacco-Free in Heart Disease | 70%* | 91% | 72%* | 83% | 83% |

| N=313 | N=830 | N=4,184 | N=1,873 | N=79,936 |

N = number of people in racial/ethnic group eligible for the measure

= group experienced substantial disparities (>10% difference in performance) compared to the highest performing population group

We found that American Indian/Alaska Native children had much lower childhood vaccination rates, while American Indian/Alaska Native adults had much lower rates of breast cancer screening, attainment of recommended weight, and being tobacco-free if they had diabetes or heart disease. Black children had much lower childhood vaccination rates, while Black adults had much lower attainment of recommended weight and blood pressure control, and Black adults who had diabetes or heart disease were much less likely to be tobacco-free.

Asian/Pacific Islander adults had much lower rates of breast and colorectal cancer screening. Hispanic/Latino adults had much lower attainment of recommended weight and those with diabetes had much lower blood sugar control. Finally, White adolescents had much lower HPV vaccination rates and White adults had much lower attainment of recommended weight.

These results are summarized in Figure 2, where the dots indicate the racial/ethnic group that was identified as highest performing for that measure and was therefore the reference group.

Figure 2:

Substantial Disparities in Wisconsin by Race/Ethnicity

Discussion

We found that American Indian/Alaska Native and Black populations experienced substantial disparities across multiple measures spanning the continuum from wellness to chronic disease management. Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino and White populations experienced substantial disparities for two measures each. Identifying disparities by race/ethnicity for specific, actionable health measures informs health systems about where strategies may be needed to address disparities in the quality of care, and informs other stakeholders about where additional resources may be needed to promote health.

Colleagues with the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute and County Health Rankings & Roadmaps have found that American Indian/Alaska Native and Black populations in Wisconsin experience considerably worse health outcomes.1,2,3 This report leveraged EHR data to identify specific health measures that help to explain some of these poor health outcomes. For communities that experience a high number of substantial disparities across multiple measures, systemic changes are needed to address root causes of health inequities in addition to focused efforts. In the United States, poorer health outcomes for people of color are the result of historical trauma and racism at the individual, institutional, and structural levels. This includes inequitable distribution of access to political power, resources, and social status in settings such as education, employment, housing, criminal justice, and healthcare.7 Investments in communities to address the social determinants of health are needed to begin to repair the effects of years of systemic racism. It is critical to improve access to health-promoting goods and services, which includes access to culturally responsive healthcare.

Targeted interventions may be effective in addressing disparities for communities that experience a smaller number of substantial disparities, in addition to addressing social determinants of health where indicated. Based on the findings of this report, this could include strategies such as removing barriers to receiving cancer screening for Asian/Pacific Islander communities8 and addressing vaccine hesitancy around HPV vaccination in White populations.9 Culturally responsive diabetes self-management programs are one evidence-based intervention to improve blood sugar control in diabetes for Hispanic/Latino populations.10 The Wisconsin Institute for Healthy Aging (WIHA) currently conducts evidence-based, diabetes self-management workshops developed by Stanford University in English and Spanish throughout the state.

The Neighborhood Health Partnerships Program (https://nhp.wisc.edu/) is addressing the need for local, timely, and actionable health data by leveraging the existing WCHQ data to provide health reports at the sub-county level. These reports may be used to identify and prioritize health improvement opportunities in neighborhoods where they are most needed to improve health equity, and to monitor the effects of interventions over time.

To eliminate health disparities, multidisciplinary partnerships are needed to improve the opportunities for all people to be healthy where they live, work, play, and age. The healthcare system has an imperative to eliminate health disparities but cannot do it alone. There is strong evidence that social and environmental factors have a greater impact on length and quality of life than clinical care. Stakeholders including health systems, policymakers, state and local public health departments, businesses, and community organizations should collaborate and synergize efforts to improve community health and work to eliminate health inequities in Wisconsin.

Funding Support:

This work was funded by a grant from the Wisconsin Partnership Program.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None declared.

Contributor Information

Maureen A. Smith, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (UW SMPH), Madison, Wis; Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, UW SMPH, Madison, Wis; Health Innovation Program, UW SMPH, Madison, Wis.

Korina A. Hendricks, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (UW SMPH), Madison, Wis; Health Innovation Program, UW SMPH, Madison, Wis.

Lauren M. Bednarz, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (UW SMPH), Madison, Wis; Health Innovation Program, UW SMPH, Madison, Wis.

Matthew Gigot, Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality, Madison, Wis.

Abbey Harburn, Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality, Madison, Wis.

Katherine J. Curtis, Department of Community and Environmental Sociology, University of Wisconsin – Madison College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, Madison, Wis; Applied Population Laboratory, Madison, Wis.

Susan R. Passmore, Collaborative Center for Health Equity, UW SMPH, Madison, Wis.

Dorothy Farrar-Edwards, Collaborative Center for Health Equity, UW SMPH, Madison, Wis; Department of Kinesiology, University of Wisconsin – Madison School of Education, Madison, Wis.

References

- 1.Friedsam D.Wisconsin’s Health Care Quality: Among the Best…and Among the Worst. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatchell K, Handrick L, Pollock EA, Timberlake K. Health of Wisconsin Report Card-2016. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings State Report 2019. Available from: https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/media/document/CHR2019_WI.pdf

- 4.National Quality Forum. A Roadmap to Reduce Health and Healthcare Disparities through Measurement. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trotter P, Lobelo F, Heather AJ. Chronic Disease Is Healthcare’s Rising-Risk. June 17, 2016; https://healthitoutcomes.com/doc/chronic-disease-is-healthcare-s-rising-risk-0001. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Glossary. National Health Interview Survey Special Topics. November 6, 2015; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/rhoi/rhoi_glossary.htm. Accessed October 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smedley BD. The lived experience of race and its health consequences. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):933–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma GX, Shive SE, Wang MQ, Tan Y. Cancer screening behaviors and barriers in Asian Americans. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(6):650–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner EL, Ding Q, Pappas LM, Henry K, Kepka D. White, affluent, educated parents are least likely to choose HPV vaccination for their children: a cross-sectional study of the National Immunization Study - teen. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):200. Published 2017 Dec 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown SA, Garcia AA, Kouzekanani K, Hanis CL. Culturally competent diabetes self-management education for Mexican Americans: the Starr County border health initiative. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]