Abstract

In mammals, adipose tissues and skeletal muscles (SkMs) play a major role in the regulation of energy homeostasis. Recent studies point to a possibility of dynamic interplay between these 2 sites during development that has pathophysiological implications. Among adipose depots, brown adipose tissue (BAT) is the major energy-utilizing organ with several metabolic features that resemble SkM. Both organs are highly vascularized, innervated, and rich in mitochondria and participate in defining the whole-body metabolic rate. Interestingly, in large mammals BAT depots undergo a striking reduction and concomitant expansion of white adipose tissue (WAT) during postnatal development that shares temporal and molecular overlap with SkM maturation. The correlation between BAT to WAT transition and muscle development is not quite apparent in rodents, the predominantly used animal model. Therefore, the major aim of this article is to highlight this process in mammals with larger body size. The developmental interplay between muscle and BAT is closely intertwined with sexual dimorphism that is greatly influenced by hormones. Recent studies have pointed out that sympathetic inputs also determine the relative recruitment of either of the sites; however, the role of gender in this process has not been studied. Intriguingly, higher BAT content during early postnatal and pubertal periods positively correlates with attainment of better musculature, a key determinant of good health. Further insight into this topic will help in detailing the developmental overlap between the 2 seemingly unrelated tissues (BAT and SkM) and design strategies to target these sites to counter metabolic syndromes.

Keywords: adipose tissue, brown fat, larger mammals, myogenesis, perinatal development, skeletal muscle

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) and skeletal muscle (SkM) are emerging as sites that determine the whole-body metabolic rate in mammals including humans [1–7]. It is proposed that these sites can be targeted to cause increased futile energy expenditure to counter obesity and related comorbidities including type 2 diabetes [8, 9]. SkM constitutes more than 40% of the body mass in healthy individuals, contributing about 50% of daily energy consumption [2, 10, 11]. On the other hand, BAT, although small, can be swiftly activated during physiological stresses like cold to produce heat and contribute significantly to the metabolic status [8]. Hence, both the sites have been implicated as “metabolic sinks” to utilize substrates (sugar and free fatty acid) creating energy demand [12–14]. Interestingly, the transcriptional regulation of BAT during early stages of development overlap with that of the SkM, indicating the possibility of coordinated maturation of these sites [15, 16]. BAT is hallmarked by the presence of large amounts of mitochondria with abundant expression of uncoupling protein (UCP)-1. The developmental pattern of BAT and expression profile of markers (UCP-1 and other transcription factors) are strikingly different between rodents and larger mammals [17, 18]. While rodents rely on active BAT throughout their lifetime, the majority of larger mammals express UCP-1 only during pre/postnatal life and it becomes negligible during adulthood.

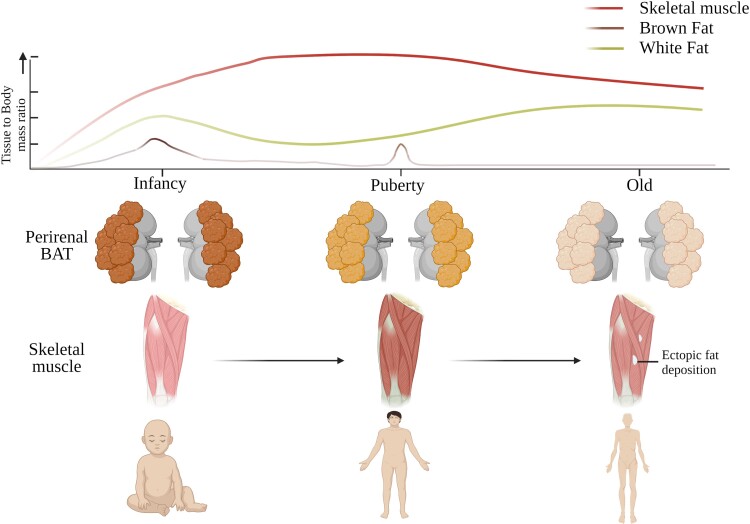

Several studies during the last decade have shown the presence of functional BAT in human adults that has catalyzed research in this field. However, subsequent studies found that the gene and protein expression profile of adult human BAT more resembles beige/brite fat of rodents than classical BAT [19]. Based on recent investigations, there is currently an evolving consensus that mouse BAT cannot fully mimic human BAT characteristics. Moreover, the relative abundance of various fat depots exhibits remarkable differences between rodent and nonrodent mammals [20–22]. The ongoing confusion relating to the functionality of BAT and beiging during adulthood can only be resolved by performing studies in animals developmentally closer to humans [23, 24]. In several mammals (ovine and bovine species) this disappearance of BAT is often closely associated with expansion of white adipose tissue (WAT). Further, this BAT to WAT transition is usually accompanied by the development of SkM in larger mammals including humans. Moreover, significant differences in SkM development have been reported between rodents and larger mammals. The overlap between muscle and BAT development in larger mammals (Fig. 1) has not been highlighted as this phenomenon is not apparent in rodents, which is the animal model predominantly used for research. Therefore, the focus of the present review is to assess structural and molecular aspects of adipose tissue (AT) and SkM development from embryo to adulthood in larger mammals such as ovine, bovine, and porcine animals. We have also gained insight from recent imaging and biochemical studies on humans to deduce the developmental interplay between the sites.

Figure 1.

Developmental maturation of muscle and brown fat. In larger mammals including human brown adipose tissue (BAT) is prominent only during perinatal stages. BAT quantity and its thermogenic capacity (ie, expression of UCP1, abundance of brown adipocytes, and mitochondrial density) sharply diminishes after birth. During the late postnatal period, the decline of BAT is reciprocally complemented by increased SkM oxidative capacity [25]. This might suggest the existence of a coordinated program that fine-tunes the metabolic functions of both sites. Further, it might be possible that SkM, after its maturation, takes over some of the metabolic functions of BAT in larger mammals. Interestingly, BAT makes a reappearance during puberty, where it closely correlates with the oxidative capacity of the SkM [26]. The oxidative capacity of SkM is highest during puberty and declines afterward. Starting from late adulthood, the appearance of ectopic fatty structures including white adipocytes in SkM gradually increases and is closely associated with metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and its comorbidities [27, 28]. Created with biorender.com.

Developmental and Distributional Homology of Adipose Tissue Between Larger Mammals and Humans

In different mammalian species ATs exhibit remarkable variation in their metabolic activity and quantity, ranging between 9% and 50% of total body weight [29, 30]. AT depots contain several types of cells including adipocytes, preadipocytes, fibroblasts, and vascular cells [31]. AT locations have classically been categorized into 2 types: WAT serves primarily as a storage site, and BAT chiefly as a thermogenic site. In addition to visible differences in color and texture, WAT and BAT also display divergences in their function, cellular architecture, and protein expression profiles. While adipocytes in WAT contain a large unilocular lipid droplet of triglycerides for storage during energy surplus states, adipocytes in BAT have multilocular smaller lipid droplets and are rich in mitochondria, which contain the unique protein named UCP-1. The function of UCP-1 is to dissipate the mitochondrial proton gradient and generate heat for maintaining the core body temperature [7].

WAT is mesodermal in origin and shows varied distribution among different mammalian groups [32]. In humans, the major WAT depots are abdominal (omental, perirenal, and intestinal) and subcutaneous (the buttocks, thighs, and abdomen) [12]. Interestingly, the adipocyte content in these WAT depots reaches maximum by roughly 6 months after birth and WAT increases its size mostly by accumulation of fat depending on nutritional availability. Hence, WAT function is highly synchronized with ambient energy status [33]. The volume of the white adipocyte grows with the increasing body size of the organism; however, distribution and the fat to body mass ratio vary across taxonomic groups. While most mammalian species have WAT in a range of 10% to 20% of total body mass, a few species show more extreme WAT content (Table 1). Chimpanzees, for instance, share a body mass range similar to humans but have comparatively much lesser volume of body fat, especially males (0.003-0.005% of total body mass) [43]. Strangely, larger mammals like elephants (mostly used as a tag of obesity) have a comparatively lesser fat to body ratio than humans and rodents [47]. Adipocyte number per body mass is more or less similar during neonatal stages in almost all mammals irrespective of their body size. The size of the adipocytes grows with increasing age and varies across species, as per their food habits and intrinsic metabolic rate. In addition, it is observed for most species, especially humans, that fat to body mass is highest during late adulthood and reduced at older ages. Interestingly, in most species females have a higher fat percentage than males, which suggests the existence of gender-specific differences in WAT function (described in “Role of Gender in Perinatal Development of SkM and AT”).

Table 1.

WAT to body mass ratio in different mammalian species

| Mammals | Body mass | Fat percentage | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young ones | Adult | |||

| Mice | 20-45 g | 2-4% | 10-22% | [34, 35] |

| Hamster | 120-160 g | 1-3% | 18-32% | [38, 39] |

| Ring tailed Lemur | 1.7-3 kg | __ | 14-26% | [40] |

| Goat | 20-50 kg | 2-5% | 14-25% | [41, 42] |

| Sheep | 20-50 kg | 2-5% | 14-25% | [39, 42] |

| Chimpanzee | 30-40 kg | __ | 0.003-8% | [43] |

| Human | 40-100 kg | 15-20% | 6-30% | [44] |

| Dolphin | 150-650 kg | __ | 18-22% | [42] |

| Camel | 210-400 kg | __ | 8-18% | [45] |

| Horse | 400-900 kg | __ | 8-20% | [46] |

| Rhinoceros | 1800-2500 kg | __ | 2-25% | [27] |

| Elephant | 1800-6300 kg | __ | 5-15% | [47] |

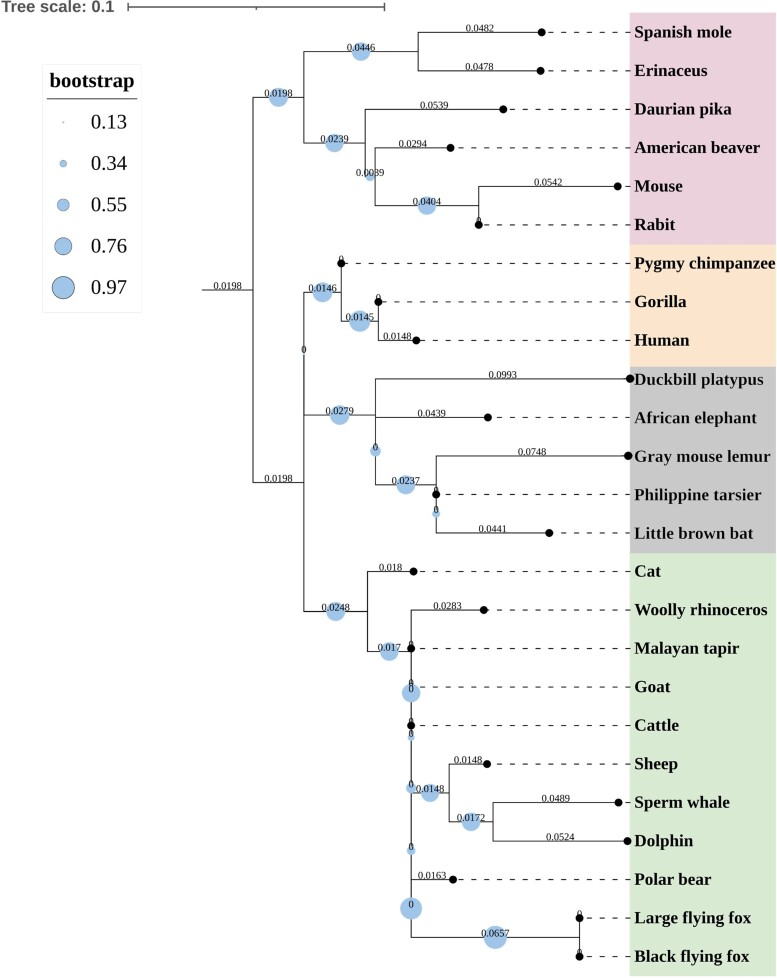

In contrast, BAT primarily generates heat by nonshivering thermogenesis in rodents [48, 49] and neonates of larger mammals [50, 51]. BAT is primarily located in interscapular, perirenal, axillary, periadrenal, gonadal, and cervical regions during the fetal and neonatal stages of both larger mammals [19, 41, 52] and rodents [7, 53]. In BAT depots of larger mammals, the abundance of brown adipocytes diminishes while that of white adipocytes increases after a few days of birth [54–57]. In adult humans, the amount of BAT observed is quite insignificant, except for those continuously exposed to cold and in patients with pheochromocytoma with abnormally high adrenergic levels [58–60]. Primary hyperaldosteronism, a condition where the adrenal secretion of aldosterone becomes abnormally high, stimulates adipogenic differentiation and inflammation in perirenal AT depot. Hyperaldosteronism has also been suggested to induce differentiation of brown preadipocytes, causing a major shift in metabolic phenotype [61, 62]. However, studies have shown the presence of metabolically active BAT in adult humans in paravertebral, cervical, axillary, and supraclavicular regions using [18F]-2-fluoro-D-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scanning [6, 63, 64]. While interscapular BAT is the predominant depot in adult rodents, it is minimal or even absent in the majority of mammalian orders (both precocial and altricial) during adulthood [53, 65]. Studies associating BAT amount in terms of body mass in different mammalian groups have not been performed so far, but phylogenetic analysis of the same has been reported. Here, we performed phylogenetic analysis of UCP-1, believed to be the basis of BAT function, for animals with varying body size from 10 different orders. In 8 orders of mammalian class with both larger and smaller body size, UCP-1 had been inactivated during evolution. UCP-1 evolution was found to be independent of body size, which suggests BAT metabolism and body mass are not related (Fig. 2). However, quantitative studies such as comparative protein expression and FDG-PET scanning analysis will provide more insight on this topic. Recent studies point out that classical BAT is present only in the interscapular region in rodents and human infants, while other BAT depots show adipocyte heterogeneity influenced by the ratio between energy intake and expenditure and have crucial metabolic implications [6, 21, 66].

Figure 2.

The phylogenetic relatedness of 11 mammalian orders based on UCP-1 sequence similarity. Maximum likelihood analysis was used to define evolutionary similarity between UCP-1 proteins taken from 25 mammalian species from 11 orders. Animals of varied body sizes were selected from each order. The phylogeny was inferred using FastTree v.2.1 program with a GTR+ GAMMA model and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Midpoint rooting was used to establish the evolutionary tree. Each node represents bootstrap values, which are indicated with varying size of solid circles.

Development of Skeletal Muscle

SkMs also undergo several structural and physiological changes during development from fetus to adulthood, largely to fulfill locomotory requirements and to withstand gravity. Muscles dedicated to posture maintenance need sustained contraction (muscle tone) contain mainly slow-twitch fibers (type I), whereas the locomotory muscles meant to support rapid contraction are enriched with fast-twitch fibers (type II) [67]. The fiber type in muscle varies greatly across species depending on their ecological adaptations and shows uniqueness in the developmental pattern.

Myogenesis and Its Molecular Regulation

SkMs are mesodermal in origin from multipotent mesenchymal stem cells and show different levels of prenatal development depending on the level of precociality [68, 69]. The differentiation of SkM is referred to as myogenesis and occurs at the level of myofibers [70]. In larger mammals, muscle fiber development during prenatal stages is categorized as primary and secondary myogenesis that occurs during early to midgestation, and has been eloquently described by earlier manuscripts [25, 68, 71]. The process of development and differentiation of SkM varies significantly between rodents and larger mammals. In rodents SkM differentiation is activated after birth, whereas in larger mammals it starts during the late gestation period [25]. A common observation during perinatal development is an increase in oxidative capacity of the SkM. Factors that demand such a change are the transition from prenatal to postnatal life, including detachment of the placental supply of oxygen and nutrients, the onset of breathing in the neonate, and the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood [67]. The postnatal growth of SkM only encompasses an increase in fiber size with no net addition of new muscle fibers [25]. However, new muscle fibers can be generated from satellite cells during postnatal life under special circumstances such as injury repair [72]. Differentiated myoblasts from satellite cells fuse with the existing SkM, thereby replenishing the lost/injured part [73].

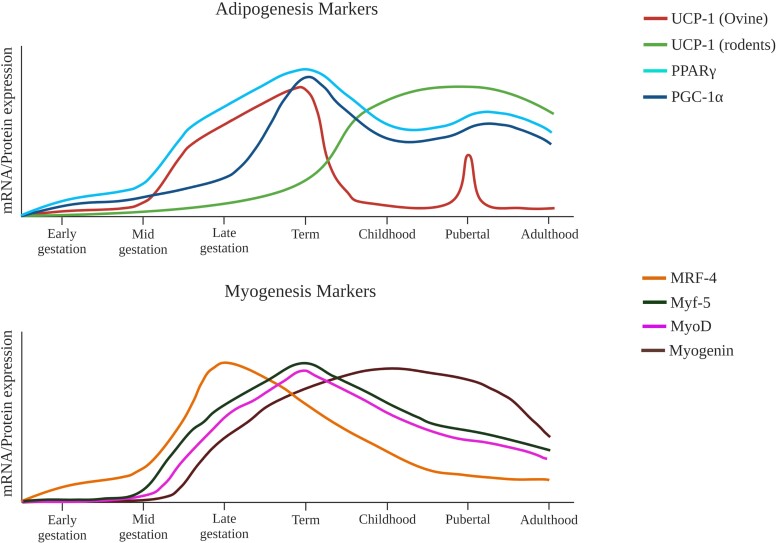

Myogenesis is a highly regulated process with sequential activation of several key transcription factors. Paired box gene family proteins along with other regulatory factors including wingless and Int induce commitment in mesenchymal stem cells, initiating myogenic regulatory factor (MRF)-4 expression [25, 74]. MRF-4 acts as a key regulator and induces expression of myogenic factor (Myf)-5 and myoblast determination protein, which drive the transition of myogenic precursor cells to myoblasts [75]. Then the myoblasts undergo proliferation, alignment, and fusion to generate immature muscle fibers, a step guided by the transcription factor myogenin (Fig. 3) [74, 78]. During this stage, a cytokine of the transforming growth factor-β family called myoststin (Mstn) plays an inhibitory role on myogenesis in the developing muscle [81]. While the Mstn mRNA starts to express during early myogenesis, reaching its peak during late gestation, several muscles continue to express Mstn until adulthood. Loss of Mstn and enhanced action of its antagonist, follistatin, have been shown to cause “hypermuscularity” in mammals, illustrating the importance of this pathway in regulating muscle development [82]. Interestingly, during postnatal development it has been observed that SkM upregulates expression of genes associated with an oxidative phenotype [83, 84]. The oxidative fibers in SkM are characterized by higher mitochondrial density and vascularization. This process is driven in part by calcineurin, which also plays a crucial role in the postnatal hypertrophy of both slow- and fast-twitch SkM [85, 86]. Further, the expression pattern of myosin heavy chain (MYH) genes shows a unique alteration during the transition from prenatal to postnatal development. MYH genes such as MYH1, MYH2, and MYH7 are upregulated in oxidative fibers (type I and IIa) with a concomitant downregulation of embryonic MYH genes such as MYH3 and MYH8 [67].

Figure 3.

Hypothetical expression of proteins associated with myogenesis and adipogenesis. (A) Expression of UCP-1 shows an interesting dichotomy between rodents and bovine/ovine species. While in rodents UCP-1 expression peaks after birth and stays high throughout life [76], in larger mammals its expression declines sharply after birth [41, 52]. UCP-1 expression is again upregulated for a short period during puberty and is correlated with muscle abundance and/or strength [77]. PGC1α and PPARγ are the major regulators of BAT functionality and follow a similar expression pattern in both rodent and bovine/ovine species. (B) Schematic showing postulated expression levels of transcription factors that mediate SkM differentiation and development in bovine/ovine species. The transcription factors that play a coordinated set of roles beginning at midgestation and continuing through the perinatal period are MRF-4, Myf-5, MyoD, and myogenin [78–80]. Interestingly, myogenin expression is upregulated last but is sustained until postpubertal life, playing a critical role in muscle maturation and hypertrophy [78, 79]. Created with biorender.com.

Sarcoplasmic Reticulum and Calcium Handling

The routine function of SkM is regulated by the major organelle called the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), the primary site of calcium (Ca2+) storage. Ca2+ handling is important not only for contraction–relaxation of the muscle but also is essential in regulating its metabolism [87]. The development of SR begins in the midgestational period in larger mammals during myoblast formation and innervations [85]. The neuromuscular contacts in primary myoblasts show expression of both subunits of the acetylcholine receptor “α” and “γ.” While γ subunit expression is only limited to fetal development, the α subunit is observed during both prenatal and postnatal development [88, 89]. After the formation of neuromuscular contacts, SR development starts during primary myogenesis, which is marked by the expression of sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium transport ATPase (SERCA) 2b, the predominant fetal isoform. At the onset of primary myogenesis, the expression of SERCA1 is also observed, which clearly suggests the existence of SR during initiation of SkM differentiation during fetal development [90]. During the perinatal period, based on SERCA1 expression, it has been suggested that the SR develops a close proximal association with the contractile apparatus. The level of Ca2+ storage inside the SR increases after birth due to upregulation of SERCA activity [91] and SR Ca2+-buffering capacity by increased expression of calsequestrin [92].

Mitochondrial Alterations During Development

A significant increase in mitochondrial biogenesis and its oxidative capacity is observed in SkM during the fetal to neonatal transition [93]. During the same period, the association (both functional and physical) between SR, mitochondria, and the contractile apparatus becomes more intimate [94]. In porcine species, SkM mitochondria are believed to utilize both carbohydrate and lipid for the generation of ATP during fetal development; however, in sheep a preferential use of carbohydrate over lipid is observed [95–97]. After birth, SkM shows marked upregulation of the enzymes associated with fat oxidation, and the mitochondria switch to free fatty acids as a primary fuel source [93, 98, 99]. A significant upregulation in the uptake of O2 during perinatal development was also observed by Smolich et al [100]. The factor that drives mitochondrial biogenesis during perinatal development has been a matter of debate. While several groups suggested Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator (PGC)-1α to be the primary regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis during myogenic development [101–103], Davies and colleagues observed no significant changes in the expression of PGC-1α during fetal development and concluded it may not be a major factor in this process [93, 104]. Calcineurin, which regulates postnatal myogenic hypertrophy, might also play a role in postnatal SkM mitochondrial biogenesis [85].

Are BAT and SkM Development Synergistically Intertwined?

Developmental Analogy Between BAT and SkM

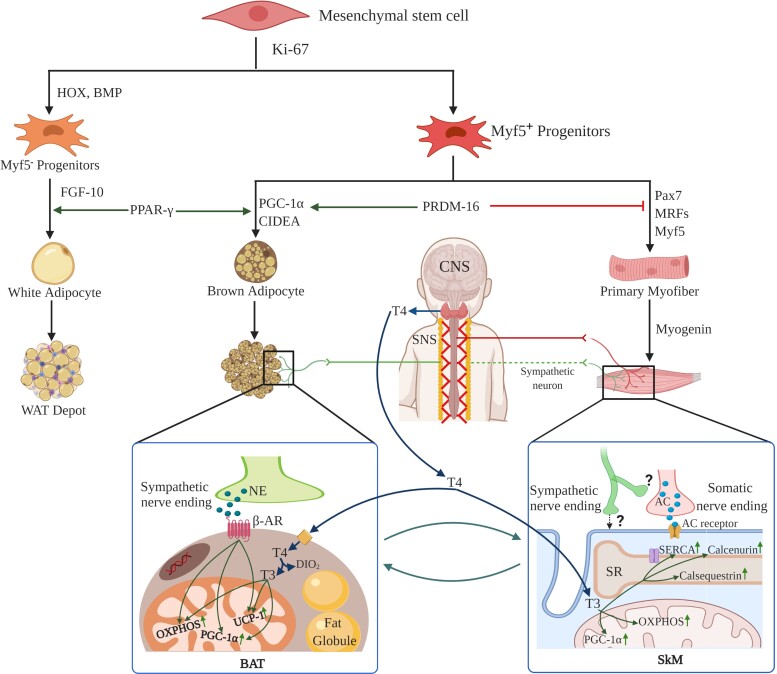

The functional difference between BAT and SkM is apparent: BAT is the major center for nonshivering thermogenesis while SkM is responsible for locomotion. Both organs use energy substrates (fat and glucose) as fuel, and due to the major overlap in their function they bear several functional and developmental similarities [16, 105–109]. These include factors associated with oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial abundance, and metabolism [16, 106]. Therefore, BAT and SkM show marked overlapping in their mitochondrial proteome, including high expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, carnitine palmitoyl transferase, complex 1 of electron transport chain, and superoxide dismutase. Recent investigations have unraveled an interesting fact that both BAT and SkM are related developmentally as they are derived from a common mesenchymal progenitor cell expressing Myf5. The brown preadipocyte and myocyte lineages diverge by the action of a transcription factor called “PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16)” regarded as the switch between BAT and SkM differentiation. Progenitor cells lacking PRDM16 undergo differentiation towards myogenic lineage, with significant upregulation in the expression of muscle-specific genes. In contrast, induction of PRDM16 in these progenitor cells commits them to the brown adipocytic lineage [110, 111]. Afterwards, myogenic genes are silenced in the brown preadipocytes by Sirtuin1-mediated deacetylation of MyoD, a major transcriptional regulator of myogenesis. It has been observed that brown preadipocytes but not white preadipocytes show a myogenic transcriptional signature, while both preadipocytes share expression of genes associated with adipocyte development, such as Hoxa7, Tbx15, and Hoxc8. Therefore, BAT is developmentally closer to SkM than WAT [106]. This process is summarized in Fig. 4. A few recent discoveries have ignited further research in the field. First is the unearthing of “brown adipocytes” inside adult SkM and that they are derived from SkM precursor cells [115–118]. In addition, the abundance of these adipocytes in SkM positively correlates with resistance against obesity. Second, PET/computed tomography scanning studies by Gilsanz et al have shown a positive correlation between the amount of BAT during neonatal/pubertal stages and SkM mass/size during adulthood [26]. Third, children with scant BAT show metabolic defects in muscles during adulthood. These studies highlight the fact that the functional intertwining of BAT and SkM has major implications in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders including obesity and diabetes.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation showing synergistic interplay between muscle and brown fat development. During development, BAT and SkM share a common Myf5+ progenitor cell while WAT originates from Myf5− progenitors. PRDM16 is a key transcriptional switch that induces commitment towards the BAT lineage, while inhibiting the SkM lineage [16, 105]. Thyroid hormone promotes metabolism and programs both sites to carry out adaptive thermogenesis. Thyroid hormone is a synergistic supplement alongside the SNS for enhancing UCP1 expression and structural modifications that are required for fully functional BAT in mice [112]. In an analogous manner, thyroid hormone also orchestrates the long-term adaptation of SkM, including the regulation of several key proteins like SERCA [113]. Moreover, BAT and SkM exhibit comparable regulation of oxidative metabolism through mitochondrial proteins, hormonal action, sympathetic innervations. [114]. All these features reflect that BAT is developmentally and functionally closer to SkM than WAT. Created with biorender.com.

Transitions in BAT and SkM During Neonatal, Pubertal, and Adolescent Life

During neonatal development, BAT and SkM undergo drastic transformation in terms of both structure and molecular expression profile [25, 119]. BAT is abundant in infants of several mammalian species [120], while minimized during postnatal life: ∼8 weeks in humans [54, 121], ∼3 to 4 weeks in goats [120], and ∼2 weeks in cattle [55]. However, studies utilizing recent advances in noninvasive imaging technologies have shown that BAT content in humans is transiently elevated during the pubertal stage in children aged 10-13 years of age [77]. The pubertal increase in BAT was gender independent and was observed in the supraclavicular area in 20% to 75% of individuals studied [122]. Interestingly, pubertal reappearance of BAT is correlated positively with SkM development, while negatively with WAT quantity [26, 123]. However, the mechanism behind its re-emergence and its synergistic regulation with SkM still remains an open question. Some studies suggested that common hormonal regulators, such as gonadal hormones, insulin, thyroid hormone, growth factors, and catecholamines, might play roles in codevelopment of the tissues [124, 125]. A possible role of cytokines has been speculated, including myokines such as irisin, which mainly upregulates brown adiposity, and adipokines such as interleukin-6, fibroblast growth factor-21, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, which enhance SkM development [126–131]. After adolescence and during adulthood, the amount of BAT in humans is drastically reduced. The loss of function of BAT with aging has been suggested to be due to the transformation of brown adipocytes into white in most of the adipose depots [132]. The detailed mechanism for this occurrence is currently lacking. Intriguingly, in humans SkM also undergoes age-related atrophy and loss of muscle mass after 40 years of age [133]. This may coincide with the brown to white transformation of adipocytes in adults and needs to be investigated to gain more insight about the synergistic development of SkM and BAT.

Hormonal and Neural Regulation of SkM and AT Development

The development of SkM and AT depots from perinatal to adulthood is regulated partly by hormones, prominently thyroid, growth hormones (GHs), and steroids [134]. Recent reports showing dysregulation of AT and SkM during prenatal development as a causative factor of metabolic disorders (such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and fatty liver) during adult life have renewed interest in this field [135–138]. Thyroid hormone is a principal regulator of SkM and AT development during all stages of life. On one hand, it enhances mitochondrial abundance by increasing PGC-1α expression, while also upregulating glucose transporter-4 expression, enhancing glycolytic capacity and thereby boosting muscle and AT metabolism [139]. Thyroid deficiency in the fetus (pig and sheep) modifies gene expression associated with fetal AT development and promotes growth of white adipocytes over brown adipocytes in the perirenal depot [140, 141]. Induced hypothyroidism in the fetus by thyroidectomy has been shown to increase expression of genetic markers of WAT, such as adiponectin, leptin, and lipoprotein lipase [142]. Thyroid hormone also increases UCP-1 and other mitochondrial proteins in cultured BAT from fetal rats and brown adiposity in large mammals during perinatal development [142–144]. A thyroid response element is located in the upstream sequences of the UCP-1 promoter and mediates the thyroid response even in adult BAT in rodents [142, 145]. In addition, thyroid hormone regulates myogenic transcription factors, such as MyoD1 and myogenin, thus mediating muscle development [146, 147]. During muscle maturation, thyroid hormone plays a critical role by modulating expression of SERCA, myosin, and Na+/K+ ATPase [148, 149]. The thyroid hormone–induced growth and differentiation of myofibers is also dependent on the activation of growth hormone receptor (GHR) and IGFs [142].

GHs regulate development of both SKM and AT during perinatal stages via GHRs in coordination with IGFs. While the loss of GHRs and IGFs leads to muscle atrophy, their overexpression causes hypertrophy [150]. Interestingly, IGF-1 mRNA is expressed increasingly from early to late gestation, indicating its role in primary and secondary myogenesis, whereas IGF-2 remains high only during early gestation [151]. IGF-1 induces myogenin and MRF4 thereby activating the Mef2c gene leading to myogenesis in the fetus [152–155]. In contrast, the role of GH and IGFs during the perinatal development of AT in large mammals has been elusive. While in vitro studies show GH and IGF-I induce adipocyte differentiation and hypertrophy [156–159], in vivo results have been conflicting [160–165]. Some groups suggest a lack of GH in fetal stages predisposes to obesity in later life, whereas others have shown higher GH levels during fetal development leads to elevated white adipogenesis [163–165]. A consensus view suggests that GH and IGFs have primary functions in AT development during early to midgestation and may have only minor fine-tuning roles during perinatal development [161]. Insulin and corticosteroids (especially cortisol) have also been suggested to have a functional interplay with IGFs and GH during the differentiation of both SkM and AT [166]. In WAT, insulin plays an anabolic role, whereas corticosteroids, especially glucocorticoids, play a catabolic role. Hyperinsulinemia was suggested to promote the growth of WAT without changing BAT differentiation; in contrast, cortisol in excess has been shown to induce a lipolytic effect facilitating triglyceride release to the serum [167–169]. This might suggest corticosteroids have distinct functions in different WAT depots, which remains poorly defined. Interestingly, a class of corticosteroid called “aldosterone” has been shown to regulate AT development in a synergistic manner. Studies suggest that aldosterone induces BAT differentiation from a preadipocyte cell line (T37i) via mineralocorticoid receptors. In return, BAT is proposed to release angiotensinogen, which subsequently augments aldosterone production via the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone pathway. This shows that aldosterone also plays a critical role in adipose metabolism in addition to its better known function in electrolyte homeostasis [170, 171]. Sex steroid hormones are known to regulate development of both AT and SkM during perinatal, pubertal, and adult life. A positive correlation is observed between gonadal hormones and the thermogenic/oxidative capacity of BAT and SkM [124, 172]. BAT expresses estrogen and androgen receptors abundantly, indicating that these steroids regulate BAT activity [173]. Decreased production of sex steroids has been proposed to reduce BAT thermogenesis due to unhindered action of cortisol during adulthood [4, 174, 175].

The development of BAT and SkM is also regulated by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). During the perinatal period, the SNS enhances the BAT phenotype by promoting UCP-1 expression and SkM activity by regulating the expression of proteins involved in fiber typing and intracellular Ca2+ channels (Fig. 4) [149, 176]. The SNS, via catecholamines and by employing other hormones such as thyroid hormone [112, 177] and prolactin, upregulates UCP-1 expression in BAT during late gestation [178]. During late neonatal stages, local adrenergic signaling is reduced partly due to increased intracellular expression of catecholamine-degrading enzymes, such as monoamine oxidase and catechol-O-methyl transferase, contributing to decreased BAT activity [179]. The SNS coordinating center, the hypothalamus, also influences brown adipogenesis via peptides like orexin [180]. Sympathetic activity is also suggested to regulate almost all aspects of SkM function including vascularization, contractility, and metabolism [181, 182]. Increasing evidence shows that sympathetic neurons are part of the neuromuscular junction and influence SkM development and expression of metabolic sensors like PGC-1α [183]. The presence of sympathetic neurites has been reported for SkM such as the diaphragm, extensor digitorum longus, gastrocnemius, and tibialis anterior based on the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase and neuropeptide Y, 2 markers of sympathetic neurons. Expression of tyrosine hydroxylase and neuropeptide Y rise during neonatal SkM development in rodents, indicating an increase in sympathetic input [184]. However, developmental regulation of SkM by the SNS in larger mammals is underexplored.

Role of Gender in Perinatal Development of SkM and AT

Sexual dimorphism in adiposity and musculature is common among adult mammals: females having greater adiposity and males exhibiting greater musculature. However, the age at which sexual dimorphism appears and its role in the developmental interplay of SkM and AT in early life is less explored. Longitudinal cohort studies show that gender-based differences in body composition are minimal at birth but acquire multifold differences during the first 6 months of the postnatal period [185]. In this period, female infants increase adiposity compared with males, while male infants increase lean body mass. These studies also demonstrate that puberty is another major window of time during which sexual dimorphism is further pronounced [31, 186, 187]. The association of adiposity accumulation during early infancy with adolescence and adult obesity supports the idea that programming during this critical window of development influences metabolism of AT throughout life [188]. Other studies in rodents have reported that gender-specific differences in SkM and AT arise during prenatal development [189, 190]. Estrogen receptor knockout mice show increased adiposity in both sexes, while androgen receptor knockout exhibits no effect on adiposity but instead impairs muscle development [191–194]. These data suggest that estrogen is an adiposity-promoting hormone while androgen is an enhancer of musculature [195, 196]. In ovine and bovine species, male fetuses exhibit greater myogenesis, whereas female fetuses show greater intestinal development with no difference in adipogenesis or fibrogenesis [197].

Studies have shown that muscles from male fetuses have higher mRNA expression of myogenic markers such as Catenin Beta 1 and Myogenic differentiation (MyoD)1 [190]. Other studies have suggested that the sexual divergence in AT and SkM is initiated during early infancy [198]. Longitudinal cohort studies of healthy term babies indicate higher subcutaneous AT volumes in females during the first 2 to 3 months than in males [187, 198, 199]. These gender-based differences can arise due to sex hormones as estrogen promotes deposition of AT in the gluteofemoral regions, whereas testosterone promotes deposition in abdominal regions [200–203]. Moreover, androgen receptors are expressed more abundantly in intra-abdominal AT than in subcutaneous AT [204]. Interestingly, there is a surge in sex-related hormones immediately after birth, termed “mini-puberty of early infancy” [205]. During the first week after birth, the circulating levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and sex hormones (testosterone and estrogen) tend to rise. The rise in sex hormones is also accompanied by increased levels of aldosterone and cortisone, resulting in hyperaldosteronism [206]. The levels of these hormones remain high for about 6 months in males and 2 to 3 years in females [205, 207, 208]. This period of mini-puberty coincides with the commencement of sexual dimorphism of SkM and AT in humans. The rise in testosterone has been suggested to be the possible reason behind enhanced musculature in males. The role of mini-puberty in the enhanced musculature in males has also been observed in male monkeys, as muscle mass diminished after blocking neonatal secretion of testosterone and gonadotrophins [209]. Compromised mini-puberty has also been suggested to trigger obesogenic metabolic imprinting [210]. Thus, mini-puberty along with SkM/AT development are possibly correlated with processes that determine the metabolic status during adulthood. Despite this, our understanding of the origins of sex differences in AT and SkM is largely speculative, as most studies to date have focused on rodents. An increased number of studies on human or physiologically closer mammals will define the exact role of gender in development of AT and SkM.

Conclusion

In the last 2 decades, there has been significant progress in the understanding of developmental regulation of AT and SkM using rodents as animal models. The discovery of beige adipocytes and active BAT in adult human has further catalyzed research in this field. However, there are several key questions that still remain poorly explored, especially related to larger mammals as these studies are resource intensive and time consuming. Some of the major unanswered questions are (1) the mediators of interplay between BAT and SkM: cytokines, miRNA or hormones; (2) the mechanism behind this interplay: while studies on rodents give a faint idea regarding the synergism between both sites, studies in larger mammals will reveal mechanistic details; and (3) the regulators of the synergism between BAT and SkM: while previously it was believed hormones and the central nervous system to be the primary regulator, recent studies project SNS to be a crucial regulator of SkM activity. This points out a possible role of the SNS behind the synergism between BAT and SkM. Further studies in larger mammals (rather than rodents) are essential to resolve these unanswered questions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bijayashree Sahu, Gourabamani Swalsingh, and Punyadhara Pani for their scientific inputs towards the outline of the review, and for their critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Leslie Rowland for careful editing and grammatical corrections.

Abbreviations

- AT

adipose tissue

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- FDG

[18F]-2-fluoro-D-2-deoxy-D-glucose

- GH

growth hormone

- GHR

growth hormone receptor

- IGF

insulin-like growth factor

- MRF

myogenic regulatory factor

- Mstn

myoststin

- Myf

myogenic factor

- MYH

myosin heavy chain

- MyoD

myogenic differentiation

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PGC

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator

- PRDM16

PR domain containing 16

- SERCA

sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium transport ATPase

- SkM

skeletal muscle

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- UCP

uncoupling protein

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Contributor Information

Sunil Pani, School of Biotechnology, KIIT University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha 751024, India.

Suchanda Dey, Center of Biotechnology, Siksha O Anusandhan, Bhubaneswar, Odisha 751030, India.

Benudhara Pati, School of Biotechnology, KIIT University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha 751024, India.

Unmod Senapati, School of Biotechnology, KIIT University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha 751024, India.

Naresh C Bal, Email: naresh.bal@kiitbiotech.ac.in, School of Biotechnology, KIIT University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha 751024, India.

Funding

This work has been partly funded by Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), DST, India (grant no. ECR/2016/001247) and DBT, India (grant no. BT/RLF/Re-entry/41/2014 and BT/PR28935/MED/30/2035/2018) to N.C.B. S.P. and S.D. are recipients of Senior Research Fellowships from Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) vide grant no 45/3/2019/PHY/BMS and AMR/Fellowship/13/2019/ECD-II respectively.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

All the data generated has been included in the submitted article.

References

- 1. Astrup A. Thermogenesis in human brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle induced by sympathomimetic stimulation. Eur J Endocrinol. 1986;112(3_Suppl a):S9–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baskin KK, Winders BR, Olson EN. Muscle as a “mediator” of systemic metabolism. Cell Metab. 2015;21(2):237–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Periasamy M, Herrera JL, Reis FC. Skeletal muscle thermogenesis and its role in whole body energy metabolism. Diabetes Metab J. 2017;41(5):327–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The changed metabolic world with human brown adipose tissue: therapeutic visions. Cell Metab. 2010;11(4):268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matsushita M, Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Kameya T, Sugie H, Saito M. Impact of brown adipose tissue on body fatness and glucose metabolism in healthy humans. Int J Obes. 2014;38(6):812–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):277–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blondin DP, Daoud A, Taylor T, et al. Four-week cold acclimation in adult humans shifts uncoupling thermogenesis from skeletal muscles to brown adipose tissue. J Physiol. 2017;595(6):2099–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Metabolic consequences of the presence or absence of the thermogenic capacity of brown adipose tissue in mice (and probably in humans). Int J Obes. 2010;34(1):S7–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gavini CK, Mukherjee S, Shukla C, et al. Leanness and heightened nonresting energy expenditure: role of skeletal muscle activity thermogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306(6):E635–E647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gallagher D, Belmonte D, Deurenberg P, et al. Organ-tissue mass measurement allows modeling of REE and metabolically active tissue mass. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(2):E239–E258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gesta S, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. Developmental origin of fat: tracking obesity to its source. Cell. 2007;131(2):242–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vornanen M. Feeling the heat: source–sink mismatch as a mechanism underlying the failure of thermal tolerance. J Exp Biol. 2020;223(16):jeb225680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Verkerke AR, Kajimura S. Oil does more than light the lamp: the multifaceted role of lipids in thermogenic fat. Dev Cell. 2021;56(10):1408–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kajimura S, Seale P, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional control of brown fat development. Cell Metab. 2010;11(4):257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, et al. PRDM16 Controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454(7207):961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaudry MJ, Campbell KL. Evolution of UCP1 transcriptional regulatory elements across the mammalian phylogeny. Front Physiol. 2017;8:670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaudry MJ, Jastroch M, Treberg JR, et al. Inactivation of thermogenic UCP1 as a historical contingency in multiple placental mammal clades. Sci Adv. 2017;3(7):e1602878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lidell ME, Betz MJ, Leinhard OD, et al. Evidence for two types of brown adipose tissue in humans. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Jong JMA, Sun W, Pires ND, et al. Human brown adipose tissue is phenocopied by classical brown adipose tissue in physiologically humanized mice. Nat Metab. 2019;1(8):830–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kajimura S, Spiegelman BM. Confounding issues in the ‘humanized’ BAT of mice. Nat Metab. 2020;2(4):303–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Jong JMA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J, Wolfrum C, Petrovic N. Reply to ‘confounding issues in the ‘humanized’ brown fat of mice’. Nat Metab. 2020;2(4):305–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Renner S, Dobenecker B, Blutke A, et al. Comparative aspects of rodent and nonrodent animal models for mechanistic and translational diabetes research. Theriogenology. 2016;86(1):406–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fuller-Jackson J-P, Henry BA. Adipose and skeletal muscle thermogenesis: studies from large animals. J Endocrinol. 2018;237(3):R99–R115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yan X, Zhu MJ, Dodson MV, Du M. Developmental programming of fetal skeletal muscle and adipose tissue development. J Genomics. 2013;1:29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gilsanz V, Chung SA, Jackson H, Dorey FJ, Hu HH. Functional brown adipose tissue is related to muscle volume in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2011;158(5):722–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rivas DA, Lessard SJ, Rice NP, et al. Diminished skeletal muscle microRNA expression with aging is associated with attenuated muscle plasticity and inhibition of IGF-1 signaling. FASEB J. 2014;28(9):4133–4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coen PM, Goodpaster BH. Role of intramyocelluar lipids in human health. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(8):391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rigamonti A, Brennand K, Lau F, Cowan CA. Rapid cellular turnover in adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hausman D, DiGirolamo M, Bartness T, Hausman G, Martin R. The biology of white adipocyte proliferation. Obes Rev. 2001;2(4):239–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2548–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pond CM. An evolutionary and functional view of mammalian adipose tissue. Proc Nutr Soc. 1992;51(3):367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Birsoy K, Festuccia WT, Laplante M. A comparative perspective on lipid storage in animals. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(7):1541–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sjögren K, Hellberg N, Bohlooly YM, et al. Body fat content can be predicted in vivo in mice using a modified dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry technique. J Nutr. 2001;131(11):2963–2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aires V, Labbé J, Deckert V, et al. Healthy adiposity and extended lifespan in obese mice fed a diet supplemented with a polyphenol-rich plant extract. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):9134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kodama A. In vivo and in vitro determinations of body fat and body water in the hamster. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1971;31(2):218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuzawa CW. Adipose tissue in human infancy and childhood: an evolutionary perspective. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;107(S27):177–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simmen B, Bayart F, Rasamimanana H, Zahariev A, Blanc S, Pasquet P. Total energy expenditure and body composition in two free-living sympatric lemurs. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mahgoub O, Lodge G. A comparative study on growth, body composition and carcass tissue distribution in Omani sheep and goats. J Agric Sci. 1998;131(3):329–339. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Demerath EW, Fields DA. Body composition assessment in the infant. Am J Hum Biol. 2014;26(3):291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Symonds ME, Pope M, Sharkey D, Budge H. Adipose tissue and fetal programming. Diabetologia. 2012;55(6):1597–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bottlenose dolphin. https://seaworld.org/animals/all-about/bottlenose-dolphin/adaptations/

- 43. Zihlman AL, Bolter DR. Body composition in pan paniscus compared with homo sapiens has implications for changes during human evolution. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(24):7466–7471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kamili A, Bengoumi M, Faye B. Assessment of body condition and body composition in camel by barymetric measurements. J Camel Practice Res. 2006; 13(1):67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kearns C, McKeever KH, Abe T. Overview of horse body composition and muscle architecture: implications for performance. Veterinary J. 2002;164(3):224–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dierenfeld ES. Rhinoceros nutrition: an overview with special reference to browsers. Verhandlungsbericht Int Symp Erkrankungen Zootiere. 1995;37:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chusyd DE, Nagy TR, Golzarri-Arroyo L, et al. Adiposity, reproductive and metabolic health, and activity levels in zoo Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). J Exp Biol. 2021;224(2):jeb219543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Himms-Hagen J. Cellular thermogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1976;38(1):315–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ricquier D, Kader J-C. Mitochondrial protein alteration in active brown fat: a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;73(3):577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gunn T, Gluckman P. Development of temperature regulation in the fetal sheep. J Dev Physiol. 1983;5(3):167–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Himms-Hagen J. Nonshivering thermogenesis. Brain Res Bull. 1984;12(2):151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Symonds ME. Brown adipose tissue growth and development. Scientifica (Cairo). 2013;2013:305763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hankir MK, Klingenspor M. Brown adipocyte glucose metabolism: a heated subject. EMBO Rep. 2018;19(9):e46404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lean M, James W, Jennings G, Trayhurn P. Brown adipose tissue uncoupling protein content in human infants, children and adults. Clin Sci. 1986;71(3):291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Casteilla L, Forest C, Robelin J, Ricquier D, Lombet A, Ailhaud G. Characterization of mitochondrial-uncoupling protein in bovine fetus and newborn calf. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1987;252(5):E627–E636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Giralt M, Casteilla L, Vinas O, et al. Iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase activity as an early event of prenatal brown-fat differentiation in bovine development. Biochem J. 1989;259(2):555–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vatnick I, Tyzbir RS, Welch JG, Hooper AP. Regression of brown adipose tissue mitochondrial function and structure in neonatal goats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1987;252(3):E391–E395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. English JT, Patel SK, Flanagan MJ. Association of pheochromocytomas with brown fat tumors. Radiology. 1973;107(2):279–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Leitner BP, Huang S, Brychta RJ, et al. Mapping of human brown adipose tissue in lean and obese young men. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(32):8649–8654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Santhanam P, Treglia G, Ahima RS. Detection of brown adipose tissue by 18F-FDG PET/CT in pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma: a systematic review. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(3):615–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu C, Zhang H, Zhang J, et al. Inflammation and fibrosis in perirenal adipose tissue of patients with aldosterone-producing adenoma. Endocrinology. 2018;159(1):227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hammoud SH, AlZaim I, Al-Dhaheri Y, Eid AH, El-Yazbi AF. Perirenal adipose tissue inflammation: novel insights linking metabolic dysfunction to renal diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:707126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Virtanen KA, Lidell ME, Orava J, et al. Functional brown adipose tissue in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1518–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lichtenbelt WD vM, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, et al. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1500–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hany TF, Gharehpapagh E, Kamel EM, Buck A, Himms-Hagen J, Von Schulthess GK. Brown adipose tissue: a factor to consider in symmetrical tracer uptake in the neck and upper chest region. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29(10):1393–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kozak LP. The genetics of brown adipocyte induction in white fat depots. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Byrne K, Vuocolo T, Gondro C, et al. A gene network switch enhances the oxidative capacity of ovine skeletal muscle during late fetal development. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bailey P, Holowacz T, Lassar AB. The origin of skeletal muscle stem cells in the embryo and the adult. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13(6):679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dearolf JL, McLellan WA, Dillaman RM, Frierson Jr D, Pabst DA. Precocial development of axial locomotor muscle in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). J Morphol. 2000;244(3):203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bentzinger CF, Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. Building muscle: molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(2):a008342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Picard B, Lefaucheur L, Berri C, Duclos MJ. Muscle fibre ontogenesis in farm animal species. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2002;42(5):415–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shefer G, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Reflections on lineage potential of skeletal muscle satellite cells: do they sometimes go MAD? Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2007;17(1):13–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tong J, Zhu M, Underwood K, Hess B, Ford S, Du M. AMP-activated protein kinase and adipogenesis in sheep fetal skeletal muscle and 3T3-L1 cells. J Anim Sci. 2008;86(6):1296–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hyatt JPK, McCall GE, Kander EM, Zhong H, Roy RR, Huey KA. PAX3/7 expression coincides with MyoD during chronic skeletal muscle overload. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38(1):861–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Molkentin JD, Olson EN. Defining the regulatory networks for muscle development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6(4):445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ribeiro MO, Bianco SD, Kaneshige M, et al. Expression of uncoupling protein 1 in mouse brown adipose tissue is thyroid hormone receptor-β isoform specific and required for adaptive thermogenesis. Endocrinology. 2010; 151(1):432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1526–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Maroto M, Reshef R, Münsterberg AE, Koester S, Goulding M, Lassar AB. Ectopic pax-3 activates MyoD and Myf-5 expression in embryonic mesoderm and neural tissue. Cell. 1997;89(1):139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Maire P, Dos Santos M, Madani R, Sakakibara I, Viaut C, Wurmser M. Myogenesis control by six transcriptional complexes. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; 2020;104:51-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80. Chal J, Pourquié O. Making muscle: skeletal myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Development. 2017;144(12):2104–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Trendelenburg AU, Meyer A, Rohner D, Boyle J, Hatakeyama S, Glass DJ. Myostatin reduces Akt/TORC1/p70S6K signaling, inhibiting myoblast differentiation and myotube size. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296(6):C1258–C1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Patruno M, Caliaro F, Maccatrozzo L, et al. Myostatin shows a specific expression pattern in pig skeletal and extraocular muscles during pre- and post-natal growth. Differentiation. 2008;76(2):168–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Buckingham M. Skeletal muscle formation in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11(4):440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Christ B, Brand-Saberi B. Limb muscle development. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46(7):905–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. de Jonge HW, van der Wiel CW, Eizema K, Weijs WA, Everts ME. Presence of SERCA and calcineurin during fetal development of porcine skeletal muscle. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54(6):641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Delling U, Tureckova J, Lim HW, De Windt LJ, Rotwein P, Molkentin JD. A calcineurin-NFATc3-dependent pathway regulates skeletal muscle differentiation and slow myosin heavy-chain expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(17):6600–6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Verkerke AR, Ferrara PJ, Lin C-T, et al. Phospholipid methylation regulates muscle metabolic rate through Ca2+ transport efficiency. Nat Metab. 2019;1(9):876–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mishina M, Takai T, Imoto K, et al. Molecular distinction between fetal and adult forms of muscle acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 1986;321(6068):406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Takahashi M, Kubo T, Mizoguchi A, Carlson CG, Endo K, Ohnishi K. Spontaneous muscle action potentials fail to develop without fetal-type acetylcholine receptors. EMBO Rep. 2002;3(7):674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Babu GJ, Bhupathy P, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Periasamy M. Differential expression of sarcolipin protein during muscle development and cardiac pathophysiology. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43(2):215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Nowack J, Vetter SG, Stalder G, et al. Muscle nonshivering thermogenesis in a feral mammal. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Murphy RM, Larkins NT, Mollica JP, Beard NA, Lamb GD. Calsequestrin content and SERCA determine normal and maximal Ca2+ storage levels in sarcoplasmic reticulum of fast-and slow-twitch fibres of rat. J Physiol. 2009;587(2):443–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Davies KL, Camm EJ, Atkinson EV, et al. Development and thyroid hormone dependence of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function towards birth. J Physiol. 2020;598(12):2453–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Boncompagni S, Pozzer D, Viscomi C, Ferreiro A, Zito E. Physical and functional cross talk between endo-sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria in skeletal muscle. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020;32(12):873–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhao L, Huang Y, Du M. Farm animals for studying muscle development and metabolism: dual purposes for animal production and human health. Anim Front. 2019;9(3):21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Brand MD, Pakay JL, Ocloo A, et al. The basal proton conductance of mitochondria depends on adenine nucleotide translocase content. Biochem J. 2005;392(2):353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Short KR, Nygren J, Barazzoni R, Levine J, Nair KS. T3 increases mitochondrial ATP production in oxidative muscle despite increased expression of UCP2 and-3. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(5):E761–E769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Clapham JC, Arch JR, Chapman H, et al. Mice overexpressing human uncoupling protein-3 in skeletal muscle are hyperphagic and lean. Nature. 2000;406(6794):415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Vidal-Puig AJ, Grujic D, Zhang C-Y, et al. Energy metabolism in uncoupling protein 3 gene knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(21):16258–16266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Smolich JJ, Soust M, Berger PJ, Walker A. Indirect relation between rises in oxygen consumption and left ventricular output at birth in lambs. Circ Res. 1992;71(2):443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Houzelle A, Jörgensen JA, Schaart G, et al. Human skeletal muscle mitochondrial dynamics in relation to oxidative capacity and insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia. 2021;64(2):424–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Finck BN, Kelly DP. PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Gan Z, Fu T, Kelly DP, Vega RB. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial remodeling in exercise and diseases. Cell Res. 2018;28(10):969–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Brown GC, Murphy MP, Jornayvaz FR, Shulman GI. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. 2010;47:69–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Kajimura S, Seale P, Kubota K, et al. Initiation of myoblast to brown fat switch by a PRDM16–C/EBP-β transcriptional complex. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1154–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Timmons JA, Wennmalm K, Larsson O, et al. Myogenic gene expression signature establishes that brown and white adipocytes originate from distinct cell lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4401–4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Farmer SR. Brown fat and skeletal muscle: unlikely cousins? Cell. 2008;134(5):726–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Walden TB, Timmons JA, Keller P, Nedergaard J, Cannon B. Distinct expression of muscle-specific microRNAs (myomirs) in brown adipocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(2):444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Bal NC, Singh S, Reis FCG, et al. Both brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle thermogenesis processes are activated during mild to severe cold adaptation in mice. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(40):16616–16625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Forner F, Foster LJ, Campanaro S, Valle G, Mann M. Quantitative proteomic comparison of rat mitochondria from muscle, heart, and liver. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(4):608–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Forner F, Kumar C, Luber CA, Fromme T, Klingenspor M, Mann M. Proteome differences between brown and white fat mitochondria reveal specialized metabolic functions. Cell Metab. 2009;10(4):324–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Silva JE, Bianco SD. Thyroid–adrenergic interactions: physiological and clinical implications. Thyroid. 2008;18(2):157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. de Meis L, Arruda AP, Carvalho DP. Role of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in thermogenesis. Biosci Rep. 2005;25(3-4):181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Seebacher F. The evolution of metabolic regulation in animals. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;224:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Almind K, Manieri M, Sivitz WI, Cinti S, Kahn CR. Ectopic brown adipose tissue in muscle provides a mechanism for differences in risk of metabolic syndrome in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(7):2366–2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Crisan M, Casteilla L, Lehr L, et al. A reservoir of brown adipocyte progenitors in human skeletal muscle. Stem Cells. 2008;26(9):2425–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Gorski T, Mathes S, Krützfeldt J. Uncoupling protein 1 expression in adipocytes derived from skeletal muscle fibro/adipogenic progenitors is under genetic and hormonal control. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9(2):384–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Liu Y, Fu W, Seese K, Yin A, Yin H. Ectopic brown adipose tissue formation within skeletal muscle after brown adipose progenitor cell transplant augments energy expenditure. FASEB J. 2019;33(8):8822–8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Schiaffino S, Rossi AC, Smerdu V, Leinwand LA, Reggiani C. Developmental myosins: expression patterns and functional significance. Skelet Muscle. 2015;5(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Trayhurn P, Thomas ME, Keith JS. Early postnatal changes in the brown fat-specific mitochondrial uncoupling protein in goat adipose tissues. Biochem Soc Trans. 1992;20(4):335S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Emery JL, Dinsdale F. Structure of periadrenal brown fat in childhood in both expected and cot deaths. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53(2):154–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Gelfand MJ, O’Hara SM, Curtwright LA, MacLean JR. Pre-medication to block [18F] FDG uptake in the brown adipose tissue of pediatric and adolescent patients. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(10):984–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Gilsanz V, Smith ML, Goodarzian F, Kim M, Wren TA, Hu HH. Changes in brown adipose tissue in boys and girls during childhood and puberty. J Pediatr. 2012;160(4):604–609.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Rodríguez-Cuenca S, Monjo M, Gianotti M, Proenza AM, Roca P. Expression of mitochondrial biogenesis-signaling factors in brown adipocytes is influenced specifically by 17β-estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(1):E340–E346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Veldhuis JD, Roemmich JN, Richmond EJ, et al. Endocrine control of body composition in infancy, childhood, and puberty. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(1):114–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Bal NC, Maurya SK, Pani S, et al. Mild cold induced thermogenesis: are BAT and skeletal muscle synergistic partners? Biosci Rep. 2017;37(5):BSR20171087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Villarroya J, Cereijo R, Villarroya F. An endocrine role for brown adipose tissue? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(5):E567–E572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Gunawardana SC, Piston DW. Reversal of type 1 diabetes in mice by brown adipose tissue transplant. Diabetes. 2012;61(3):674–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Stanford KI, Goodyear LJ. Muscle-adipose tissue cross talk. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(8):a029801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Pedersen BK, Febbraio M. Muscle-derived interleukin-6—a possible link between skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, liver, and brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(5):371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(4):1379–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Gilsanz V, Hu HH, Kajimura S. Relevance of brown adipose tissue in infancy and adolescence. Pediatr Res. 2013;73(1):3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Tumasian RA, Harish A, Kundu G, et al. Skeletal muscle transcriptome in healthy aging. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Saltiel AR. You are what you secrete. Nat Med. 2001;7(8):887–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Wong S, Ng S, Didi M. Children with congenital hypothyroidism are at risk of adult obesity due to early adiposity rebound. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61(4):441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Godfrey KM, Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental origins of metabolic disease: life course and intergenerational perspectives. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(4):199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Friedman JE. Developmental programming of obesity and diabetes in mouse, monkey, and man in 2018: where are we headed? Diabetes. 2018;67(11):2137–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Simeoni U, Armengaud JB, Siddeek B, Tolsa JF. Perinatal origins of adult disease. Neonatology. 2018;113(4):393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Harper M-E, Seifert EL. Thyroid hormone effects on mitochondrial energetics. Thyroid. 2008;18(2):145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Hausman G, Wright J. Cytochemical studies of adipose tissue-associated blood vessels in untreated and thyroxine-treated hypophysectomized pig fetuses. J Anim Sci. 1996;74(2):354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Hausman GJ, Wright JT. Ontogeny of the response to thyroxine (T4) in the porcine Fetus: interrelationships between serum T4, serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and differentiation of skin and several adipose tissues. Obes Res 1996;4(3):283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Harris SE, De Blasio MJ, Zhao X, et al. Thyroid deficiency before birth alters the adipose transcriptome to promote overgrowth of white adipose tissue and impair thermogenic capacity. Thyroid. 2020;30(6):794–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Rogers NH. Brown adipose tissue during puberty and with aging. Ann Med. 2015;47(2):142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Whittle A. Searching for ways to switch on brown fat: are we getting warmer? J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;49(2):R79–R87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Villarroya F, Peyrou M, Giralt M. Transcriptional regulation of the uncoupling protein-1 gene. Biochimie. 2017;134:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Forhead A, Li J, Gilmour R, Dauncey M, Fowden A. Thyroid hormones and the mRNA of the GH receptor and IGFs in skeletal muscle of fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282(1):E80–E86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Carnac G, Albagli-Curiel O, Vandromme M, et al. 3, 5, 3'-Triiodothyronine positively regulates both MyoD1 gene transcription and terminal differentiation in C2 myoblasts. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6(8):1185–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Dauncey M, Harrison A. Developmental regulation of cation pumps in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1996;156(3):313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Cairns SP, Borrani F. β-Adrenergic modulation of skeletal muscle contraction: key role of excitation-contraction coupling. J Physiol. 2015;593(21):4713–4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Coleman ME, DeMayo F, Yin KC, et al. Myogenic vector expression of insulin-like growth factor I stimulates muscle cell differentiation and myofiber hypertrophy in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(20):12109–12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Ernst CW, McFarland DC, White ME. Expression of insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II), IGF binding protein-2 and myogenin during differentiation of myogenic satellite cells derived from the Turkey. Differentiation. 1996;61(1):25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Rosenthal SM, Cheng Z-Q. Opposing early and late effects of insulin-like growth factor I on differentiation and the cell cycle regulatory retinoblastoma protein in skeletal myoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(22):10307–10311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Engert JC, Berglund EB, Rosenthal N. Proliferation precedes differentiation in IGF-I-stimulated myogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1996;135(2):431–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Musarò A, Rosenthal N. Maturation of the myogenic program is induced by postmitotic expression of insulin-like growth factor I. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(4):3115–3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Oksbjerg N, Gondret F, Vestergaard M. Basic principles of muscle development and growth in meat-producing mammals as affected by the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2004;27(3):219–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Wallace JM, Matsuzaki M, Milne J, Aitken R. Late but not early gestational maternal growth hormone treatment increases fetal adiposity in overnourished adolescent sheep. Biol Reprod. 2006;75(2):231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Oberbauer AM, Stern JS, Johnson PR, et al. Body composition of inactivated growth hormone (oMt1a-oGH) transgenic mice: generation of an obese phenotype. Growth Dev Aging. 1997;61(3-4):169–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Wabitsch M, Hauner H, Heinze E, Teller WM. The role of growth hormone/insulin-like growth factors in adipocyte differentiation. Metab Clin Exp. 1995;44:45–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Rommel C, Bodine SC, Clarke BA, et al. Mediation of IGF-1-induced skeletal myotube hypertrophy by PI (3) K/Akt/mTOR and PI (3) K/Akt/GSK3 pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(11):1009–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Jensen RBB, Chellakooty M, Vielwerth S, et al. Intrauterine growth retardation and consequences for endocrine and cardiovascular diseases in adult life: does insulin-like growth factor-I play a role? Horm Res Paediatr. 2003;60(Suppl 3):136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Oberbauer AM. Developmental programming: the role of growth hormone. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2015;6(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Louveau I, Gondret F. Regulation of development and metabolism of adipose tissue by growth hormone and the insulin-like growth factor system. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2004;27(3):241–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Bartke A, Chandrashekar V, Turyn D, et al. Effects of growth hormone overexpression and growth hormone resistance on neuroendocrine and reproductive functions in transgenic and knock-out mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;222(2):113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Mauras N, Haymond MW. Are the metabolic effects of GH and IGF-I separable? Growth Horm IGF Res. 2005;15(1):19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Blüher S, Kratzsch J, Kiess W. Insulin-like growth factor I, growth hormone and insulin in white adipose tissue. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19(4):577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Li J, Forhead A, Dauncey M, Gilmour R, Fowden A. Control of growth hormone receptor and insulin-like growth factor-I expression by cortisol in ovine fetal skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2002;541(2):581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2001;414(6865):799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Zezulak KM, Green H. The generation of insulin-like growth factor-1–sensitive cells by growth hormone action. Science. 1986;233(4763):551–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Nixon T, Green H. Contribution of growth hormone to the adipogenic activity of serum. Endocrinology. 1984;114(2):527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Penfornis P, Viengchareun S, Le Menuet D, Cluzeaud F, Zennaro M-C, Lombès M. The mineralocorticoid receptor mediates aldosterone-induced differentiation of T37i cells into brown adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279(2):E386–E394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Engeli S, Schling P, Gorzelniak K, et al. The adipose-tissue renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system: role in the metabolic syndrome? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35(6):807–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Yanase T, Fan W, Kyoya K, et al. Androgens and metabolic syndrome: lessons from androgen receptor knock out (ARKO) mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;109(3-5):254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Abelenda M, Nava MP, Fernández A, Puerta ML. Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis in testosterone-treated rats. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1992;126(5):434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Soumano K, Desbiens S, Rabelo R, Bakopanos E, Camirand A, Silva JE. Glucocorticoids inhibit the transcriptional response of the uncoupling protein-1 gene to adrenergic stimulation in a brown adipose cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;165(1-2):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Wasco EC, Martinez E, Grant KS, St. Germain EA, St. Germain DL, Galton VA. Determinants of iodothyronine deiodinase activities in rodent uterus. Endocrinology. 2003;144(10):4253–4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Khan MM, Lustrino D, Silveira WA, et al. Sympathetic innervation controls homeostasis of neuromuscular junctions in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(3):746–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Silva JE, Larsen PR. Adrenergic activation of triiodothyronine production in brown adipose tissue. Nature. 1983;305(5936):712–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Budge H, Edwards LJ, McMillen IC, et al. Nutritional manipulation of fetal adipose tissue deposition and uncoupling protein 1 messenger RNA abundance in the sheep: differential effects of timing and duration. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(1):359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Mancuso P, Bouchard B. The impact of aging on adipose function and adipokine synthesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. Sellayah D, Bharaj P, Sikder D. Orexin is required for brown adipose tissue development, differentiation, and function. Cell Metab. 2011;14(4):478–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181. Higashihara T, Nishi H, Takemura K, et al. β2-adrenergic receptor agonist counteracts skeletal muscle atrophy and oxidative stress in uremic mice. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182. Voltarelli VA, Coronado M, Gonçalves Fernandes L, et al. β2-Adrenergic signaling modulates mitochondrial function and morphology in skeletal muscle in response to aerobic exercise. Cells. 2021;10(1):146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]