Abstract

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a common and refractory inflammation of the kidneys caused by systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis and therapies at this stage are inefficient or have severe side effects. In recent years, nanomedicines show great potential for imaging diagnosis and controlled drug release. Herein, we developed a polydopamine (PDA)-based nanocarrier modified with Fe3O4 and Pt nanoparticles and loaded with necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) for the bimodal imaging and therapy of LN. Results demonstrate that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanocarrier exhibits good biocompatibility. Nec-1, as an inhibitor of receptor-interacting protein 1 kinase, can be used to inhibit receptor-interacting protein 1 kinase activity and then reduces inflammation due to LN. Experiments in vitro and in the LN mouse model confirmed that the nanocarrier can reduce neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) production by RIPK1 and alleviate the progression of inflammation. Previous studies proved that Pt nanoparticles can catalyze H2O2 to produce oxygen. A blood oxygen graph of mouse photoacoustic tomography confirmed that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 can generate oxygen to fight against the hypoxic microenvironment of LN. PDA and Fe3O4 are used as photographic developers for photoacoustic or magnetic resonance imaging. The preliminary imaging results support Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 potential for photoacoustic/magnetic resonance dual-mode imaging, which can accurately and non-invasively monitor microscopic changes due to diseases. Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 combining these advantages exhibited outstanding performance in LN imaging and therapy. This work offers valuable insights into LN diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: theranostics, lupus nephritis, multi-mode imaging, collaborative treatment

1. Introduction

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a common and refractory inflammation of the kidneys caused by systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which occurs within 6–36 months after diagnosis [1]. Diagnostic and therapeutic tools for LN are currently available, but 14–33% of patients fail to respond, and LN remains a refractory disease [2,3,4]. The diagnosis of LN mainly relies on biomarker-based tests in the blood and histological analysis of kidney biopsies [5]. LN is mainly treated through immunosuppressive therapy and treatments with anti-inflammatory drugs [1,6]. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and the hypoxia microenvironment of the kidney plays a key role in the pathogenic course of LN [7,8,9,10]. The formation of NETs can be induced by receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), which aggravates inflammation [5,6,7]. NETs are highly expressed in the kidneys of patients with SLE, leading to severe organ damage [11,12]. In addition, sustained inflammation and immune responses are accompanied by an increased oxygen consumption, resulting in hypoxia in local inflammatory tissues, which further drives inflammation and the formation of extracellular traps in LN [8,13]. Immunosuppression therapy is often used to treat LN. However, it does not always provide adequate control of the disease and carries a high risk of treatment intolerance and dose-increasing toxicity, and a high recurrence rate because of adverse pharmacokinetics and biodistribution.

Owing to the enormous potential of imaging diagnosis and controlled drug release, nanomedicines have been applied to biomedicine. The development of diagnostic nanoparticles provides more accurate enhanced images. Therapeutic nanoparticles improve the accumulation and release of drugs at the pathological site, increase the therapeutic efficacy in general, and reduce the incidence and intensity of side effects. The theranostic purpose can be well achieved by integrating the diagnostic and therapeutic drugs into a single NP [14,15,16]. Polydopamine (PDA) has become a subject of great interest in nanomedicine because of its excellent properties, including good biocompatibility, easy preparation, easy modification, and high near-infrared absorption [17,18,19,20]. In addition, PDA can be used as a free radical scavenger because of its rich phenolic groups and eliminates reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced in inflammatory reactions [21,22]. Moreover, PDA is an outstanding photoacoustic imaging contrast agent because of its strong absorption in the near-infrared region [23,24]. Superparamagnetic complexes, such as SPIO, ferric oxide, and Fe3O4, have been successfully used in MRI to detect LN and other tissue sites of inflammation [25,26]. When injected into the bloodstream, these nanoparticles are absorbed by inflammatory cells and accumulate in inflammatory tissues, reducing signal attenuation on T2-weighted images, which can be used in detecting inflammation [27]. Combinations of PDA and superparamagnetic complexes can be used in visualizing the molecular changes of LN and monitoring microhemodynamic changes in the kidney through PA/MR bimodal imaging. Precious metal platinum (Pt) is used in oxygen production in vivo because it has high catalase catalytic activity, good biocompatibility, and high cell uptake efficiency [28]. In our previous study, we prepared Pt-based nanomaterials that significantly improve the hypoxia microenvironment of tumors by in situ catalytic hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [29].

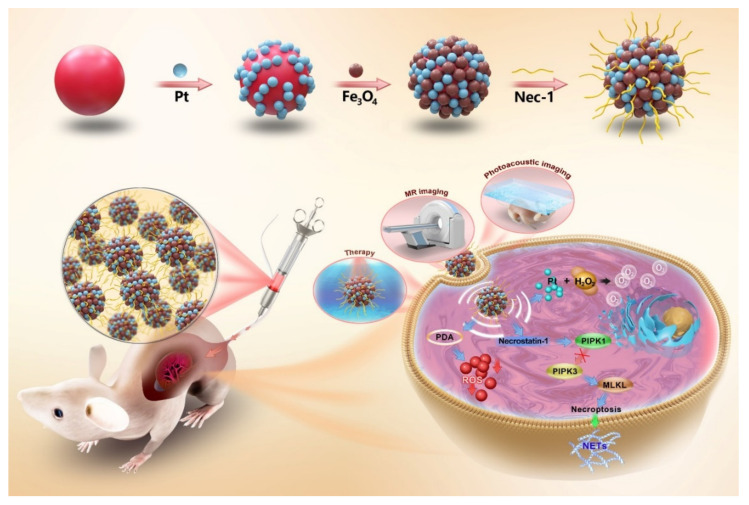

In this work, we prepared PDA-based nanoparticles modified with Fe3O4 and Pt nanoparticles (PDA@Pt-Fe3O4) and loaded with necrostatin-1 (Nec-1), an inhibitor of RIPK1, for the bimodal imaging and therapy of LN (Figure 1). Nec-1 is used to inhibit RIPK1 kinase activity and further reduces inflammation due to LN. PDA and Fe3O4 have been used as photographic developers for photoacoustic/magnetic resonance dual-mode imaging for the accurate and non-invasive monitoring of microscopic changes caused by diseases. Pt nanoparticles are used to alleviate inflammation induced by hypoxia. This work offers valuable insights into LN diagnosis and therapy.

Figure 1.

The preparation process of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles and schematic illustration of the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles for imaging and therapy of LN. Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles consisted of a polydopamine (PDA)-based nanocarrier modified with Fe3O4 and platinum (Pt) and loaded with necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) for photoacoustic/magnetic resonance dual-mode imaging and therapy of LN. As a necroptosis inhibitor, Nec-1 selectively targets the kinase activity of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), and thus inhibits mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) phosphorylation. Nec-1 is used to inhibit neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) release and further reduces inflammation due to LN. PDA can be used as a free radical scavenger and eliminates reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced in inflammatory reactions. Moreover, Pt is used in oxygen production because of its high catalase catalytic activity.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Ammonium hydroxide (NH3·H2O, 25–28%, w/w), dopamine, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, K30), hydrogen hexachloroplatinate (H2PtCl6), ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O), ferrous chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O) and Nec-1 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Shanghai, China). Anhydrous ethanol was obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) was purchased from Beyotime (Wuhan, China). Sytox Green was purchased from Keygen Biotech (Wuhan, China). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was obtained from KH2PO4, Na2HPO4, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, and deionized water. All the chemical reagents were of analytical grade and used directly as received. A Milli-Q water purification system (Bedford, MA, USA) was used in obtaining deionized water.

2.2. Preparation of Polydopamine (PDA) Nanoparticles

Firstly, 18 mL of ultrapure water and 8 mL ethanol were mixed and stirred gently at 30 °C. Secondly, 0.6 mL of NH3·H2O was added, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. Then, 2 mL of dopamine solution (50 mg/mL) and hydrochloride were added [30]. The resulting solution was stirred for 18 h. Finally, the solution was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min and washed three times with ultrapure water for the preparation of PDA nanoparticles.

2.3. Preparation of PDA@Pt Nanoparticles

PDA@Pt nanoparticles were synthesized by a chemical reduction method [31]. In brief, 10 mg of PDA and 50 mg of PVP were dispersed in 100 mL of ethanol under ultrasonic conditions. Then, 0.8 mL of 120 × 10−3 mol/L H2PtCl6 was added to the above solution, which was then subjected to ultrasonic stirring for 30 min and reflux at 90 °C for 12 h. PDA@Pt nanoparticles were prepared by washing, centrifugation, and dispersion with deionized water.

2.4. Preparation of PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

Approximately 15 mg of PDA@Pt nanoparticles were dispersed in 55 mL of deoxidized ultrapure water to form a uniform suspension. Subsequently, 54 mg of FeCl3·6H2O and 23 mg of FeCl2·4H2O were added to the suspension. A water bath was heated to 85 °C, and when the temperature was stable, 3.75 mL of NH3·H2O was added, and stirring was continued for 1 h [32]. The PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles were prepared by washing several times with ethanol and dispersing them in water.

2.5. General Characterization

The morphology of nanoparticles was recorded with high-resolution transmission electron microscopy at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV (JEM-2100, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The size and zeta potential of the nanoparticles were determined through dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis using a Zetasizer Nano ZS equipment (Malvern Instruments Nano ZSE, UK). Each sample was measured five times. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra were obtained using a TENSOR II spectrometer (Bruker, DER). Crystallinity was measured by powder X-ray diffraction on a D/Max-2550 PC X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) with Cu-Ka radiation. UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra were measured on a Cary 5000 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent, CA, USA). Pathological images were obtained with an upright metallurgical microscope (Carl Zeiss, Axio Imager A2, Jena, Germany). The concentrations of Fe and Pt solutions were measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (710-ES, Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Pathological images were obtained with an upright metallurgical microscope (Carl Zeiss, Axio Imager A2, Jena, Germany).

2.6. Nec-1 Loading and Release

Nec-1 was loaded on the PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles by mixing 2 mL of freshly prepared Nec-1 solution (0.5 mg/mL) with 5 mg of PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The mixed solution was stirred in the dark for 48 h at room temperature to reach an equilibrium state. Then, the remaining unbound Nec-1 was wiped off through centrifugation. The loading capacity of Nec-1 was calculated by the following equation:

| (1) |

Nec-1 released from PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles was tested as follows. Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles (2.5 mg) were dispersed in 5.0 mL of PBS solution at pH 6.5 and pH 7.4 successively. The solutions were stirred in a shaker (Boxun Instrument Co., Ltd., Changsha, China) at 37 °C and subjected to centrifugation at certain time points. The supernatants were collected, and the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles at the bottom were re-dispersed in equal volumes of fresh PBS solutions under ultrasonication. The amounts of released Nec-1 in corresponding PBS supernatants (pH 6.5 and 7.4) at various times were obtained via the characteristic absorption of Nec-1.

2.7. Evaluating the Formation of NETs

The PMA-induced formation of NETs in HL-60 cells was investigated, and the amount of the NETs was determined in vitro. The cells were induced to differentiate into neutrophil-like granulocytes by DMSO. Then, neutrophil-like granulocytes (1.5 × 106 cells/well in 200 μL of medium) were seeded into black, flatbottomed, and 96-well plates and incubated for 4 h in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The medium was supplemented with PBS, 50 μg/mL Nec-1/mPDA@Pt-Fe3O4, and 25 nM PMA. Another medium without 25 nM PMA was used. Extracellular DNA was stained with the membrane-impermeable DNA-binding dye Sytox Green. The plates were analyzed using a Spectra Max M3 fluorescent plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 520 nm [12].

2.8. Animal Model Establishment

Female C57BL/6 mice (15 weeks old) were purchased from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (Foshan, China). Animal work was performed using the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female C57BL/6 mice aged 5–6 weeks were intraperitoneally injected with 0.5 mL of pristane. The urinary protein content of the mice was detected by Albustix dipsticks every week, and the symptoms and signs in the mice were observed. When there were 3 + urine proteins on the paper, and the mice’s paws were pale and cold with ascites, the model was considered successfully established [33].

2.9. MR Imaging and Photoacoustic Imaging of the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4

Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 at different concentrations (0.8, 0.4, 0.2, 0.1 and 0 mM) was dispersed in 3% agar mixture. All samples were placed in test tubes and scanned with 3.0T MRI with a small animal coil (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands). The imaging parameters for axial T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) sequence were as follows: relaxation time (TR) = 2408 ms, echo time (TE) = 100 ms, slice thickness = 3.5 mm, slice spacing = 0.35 mm, field of view = 180 mm × 180 mm, matrix = 328 × 251, and scanning time = 82 s.

Nanoprobes with different concentrations (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 mg/mL) were poured into plastic tubes, which were placed in a photoacoustic microscope imager (developed by Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital) for scanning. The photoacoustic imager had a laser wavelength of 532 nm.

Photoacoustic imaging and MR imaging in vivo were performed on the mice in the model group. After anesthesia administration, lupus mice were placed in a 3.0T MR imager (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) and scanned with a 3.0T MRI with a small animal coil (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands). Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoprobe (100 μL) was injected into the tail vein of each mouse at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. T2WI was performed at baseline (prior to injection) and 5 min after Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 injection. The imaging parameters for coronal T2WI sequence were as follows: TR = 2500 ms, TE = 100 ms, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice spacing = 0.3 mm, field of view = 80 mm × 80 mm, matrix = 160 × 119, and scanning time = 65 s.

Lupus mice were scanned by photoacoustic tomography (VisualSonics, Vevo LAZR, Toronto, Canada). The mice were fixed in photoacoustic tomography, and the renal photoacoustic images were collected. A 100 μL Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoprobe was injected into the tail vein of mice at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. After 5 min, photoacoustic imaging was performed on the kidney again, and the intensities of photoacoustic signals in the kidney region before and after the injection of the nanoprobe were compared.

2.10. Therapeutic Effect of Nec-1/mPDA@Pt-Fe3O4 on LN

LN mice (16 weeks) were randomly divided into three groups, including control, model, and Nec-1/mPDA@Pt-Fe3O4 groups. Intraperitoneally, Nec-1 nanoprobes were injected at a concentration of 1 mg/mL and a dosage of 6 mg/kg/day. All mice were treated for 3 weeks, their body weights were measured every 3 days and urinary protein excretion was measured every week. They were killed at the end of the experiment. Mouse kidneys were collected and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and structural changes in the kidney tissues were observed. Then, myeloperoxidase (MPO; antibodies to neutrophil markers) was used to stain the kidney tissues. Finally, an upright metallographic microscope was used for image acquisition. Differences in treatment outcomes among groups were analyzed by t-test.

The renal areas of different groups were scanned with a 3.0T MRI (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands). The imaging parameters for coronal intravoxel incoherent motion imaging (IVIM-DWI) sequence were as follows: TR = 3000 ms, TE = 61 ms, scanning layer thickness = 2.4 mm, layer spacing = 0.24 mm, field of vision = 70 mm × 66 mm, matrix = 64 × 72, and scanning time = 189 s. IVIM-DWI image post-processing: Philips post-processing workstation was used to analyze the image, delineate the renal parenchyma area of interest, and calculate the perfusion score F value.

Lupus mice were scanned by photoacoustic tomography (VisualSonics, Vevo LAZR, Toronto, Canada). After anesthesia, the mice were fixed in photoacoustic tomography, the renal blood oxygen images of each group were collected, and the renal blood oxygen status of each group was compared with that of another.

2.11. Biosafety Assessment of Nec-1/mPDA@Pt-Fe3O4

Mice were randomly divided into the experimental group and the control group, and the experimental group was injected with Nec-1/mPDA@Pt-Fe3O4 (1mg/mL, 6mg/kg/d Necrostatin-1 equiv.) via the intraperitoneal injection, and the control group was injected with saline (100 mL). The hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, and kidneys of the mice were collected for histological analysis.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Experimental results were shown as the mean ± standard deviation. All the statistical analyses were performed by Statistical Product and Service Solutions for Windows (SPSS, version 22.0, IBM Co., Ltd., Armonk, NY, USA). The difference between the iVIM-DWI sequence renal perfusion scores and percentage content of NETs released by neutrophils of different groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. p < 0.05 indicated statistical difference.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4

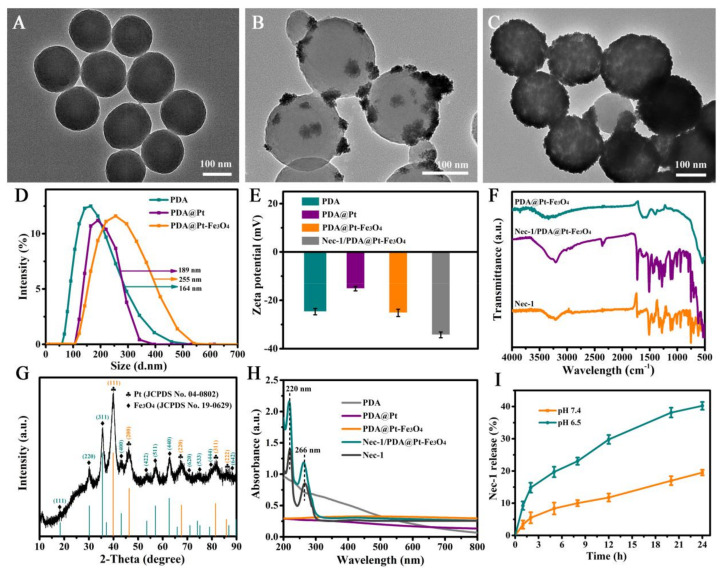

The Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles were designed according to Figure 1. PDA nanoparticles were prepared by an oxidation self-polymerization method. Pt was then coated on the surface of PDA by a chemical reduction method for the preparation of PDA@Pt nanoparticles. Fe3+/Fe2+ were converted into Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the surface of PDA@Pt nanoparticles in the presence of ammonium hydroxide. As demonstrated in Figure 2A, the prepared PDA nanoparticles were monodispersed with well-defined spherical shapes and had a homogeneous diameter of ~142 nm. Figure 2B shows that the PDA@Pt nanoparticles were constructed successfully. After Fe3O4 coating, PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 formed (Figure 2C). The results provided indirect proof of the success of each step. We measured the hydrated particle sizes of PDA, PDA@Pt, and PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 by DLS (Figure 2D,E), and the average diameters were ~164, ~189, and ~255 nm, which were slightly larger than the corresponding TEM results because DLS showed an average hydrodynamic particle size. Subsequently, the zeta potentials of these nanoparticles were investigated (Figure 2E). The zeta potentials of PDA were negative on account of the existence of phenolic hydroxyl groups on the surface. The zeta potential of PDA@Pt increased to accommodate the negative hydroxyl in PDA. The zeta potential value of PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 decreased from −15.2 mV to −25.3 mV, which may be attributed to the successful Fe3O4 coating. The zeta potential of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 decreased to −34.6 mV, which may be due to the ionization of Nec-1. These results showed that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 had been successfully prepared.

Figure 2.

The TEM images of (A) PDA nanoparticles, (B) PDA@Pt nanoparticles, (C) PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. (D) The dynamic light scattering of PDA, PDA@Pt, and PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles, respectively. (E) The zeta potential of PDA, PDA@Pt, PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, and Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles, respectively. (F) FTIR spectra of the PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, and free Nec-1. (G) XRD pattern of the PDA@Pt-Fe3O4. (H) UV-Vis-NIR spectra of the aqueous solutions of PDA, PDA@Pt, PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, and free Nec-1. (I) Cumulative Nec-1 release of the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles in PBS at pH 6.5 and 7.4.

To verify the encapsulation of Nec-1, we compared the FTIR spectra of PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, and free Nec-1. As shown in Figure 2F, the characteristic peak at 512 cm−1 in the spectra of PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 should be assigned to the Fe–O bond vibration of Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Compared with the characteristic peaks of Nec-1, Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 was successfully prepared. Subsequently, the X-ray diffraction pattern of PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 is presented in Figure 2G. The characteristic peaks of Pt nanocrystals (JCPDS No. 04-0802) and Fe3O4 nanocrystals (JCPDS No. 19-0629) demonstrated that Pt nanocrystals and Fe3O4 were successfully assembled in the final nanoparticles.

Figure 2H shows the UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra of PDA, PDA@Pt, PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, and free Nec-1. The aqueous solution of PDA, PDA@Pt, and PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 revealed no obvious absorption peaks. The distinct characteristic absorption peak at 220 and 266 nm of Nec-1 appeared in the spectra of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, indicating that Nec-1 was successfully loaded in the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles. In addition, we calculated the loading capacity of Nec-1. As indicated by the UV-Vis-NIR spectra of PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 and Nec-1, the Nec-1 loading capacity in Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles was 17% (by weight). These results showed that we successfully prepared Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

Further, the Nec-1 release properties of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles were studied in PBS with pH 6.5 (simulated LN lesion environment) and pH 7.4 (simulated physiological condition), respectively. The results (Figure 2I) showed that 40.2% of Nec-1 was released under pH 6.5 within 24 h, much higher than that at pH 7.4, which is due to the fact that the -HC=N- bonds on the surface of nanoparticles can be disrupted in an acidic lupus nephritis environment, resulting in the specific release of Nec-1 at the lesion site [34]. The results demonstrated that the Nec-1 release from Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 nanoparticles can be controlled by pH. The high release is beneficial for the treatment of lupus nephritis as it rapidly produces effective local Nec-1 concentrations.

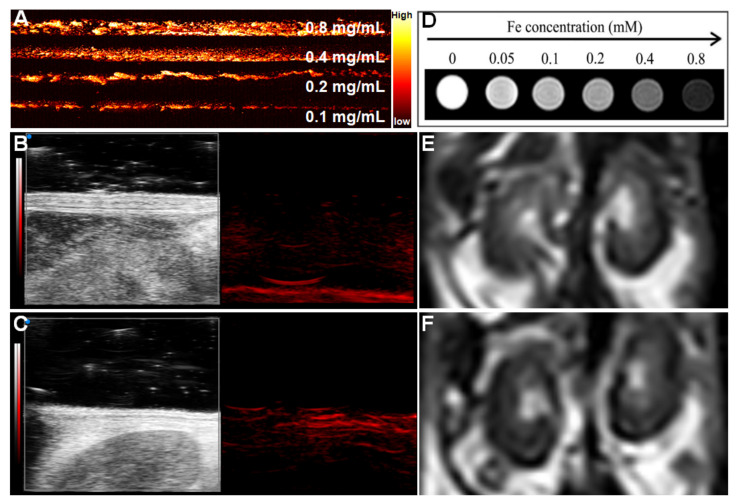

3.2. PA and MR Dual-Mode Image Tracking

To explore the PA performance of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, we used a variable wavelength pulsed laser (680–970 nm) and an input laser with a frequency of 30 MHz. The results showed that PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 exhibited extremely strong PA signal intensity, and the intensity of the photoacoustic signal increased with PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 concentration (Figure 3A) possibly because of the PA-enhancing effect of PDA [23]. In addition, the photoacoustic image of mouse kidneys before and after injection of 100 μL Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 at a concentration of 1 mg/mL was investigated. The results are shown in Figure 3B,C. After the injection of nanoprobes, the photoacoustic signal of blood vessels in the renal region was significantly enhanced, and the renal contour became clear, indicating that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 had an excellent performance in PA images.

Figure 3.

Photoacoustic/magnetic resonance dual-mode imaging. (A) Photoacoustic imaging at different concentrations of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 in vitro, Photoacoustic imaging of mice kidney before (B) and after (C) adding 1mg/mL Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 in vivo. (D) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in vitro at different concentrations of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4. Magnetic resonance imaging of mice kidneys before (E) and after (F) adding Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 in vivo.

The MRI performance of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 was investigated with 3.0T MRI. The detailed parameters are shown in the Methods section. As shown in Figure 3D, the T2-weighted signal intensity decreased gradually with increasing concentration. We also investigated MRI performance in vivo. As shown in Figure 3E,F, after Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 was injected into the mice in vivo, the T2-weighted signal was negatively enhanced.

The above results showed that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 is an outstanding PA/MR dual-mode imaging agent.

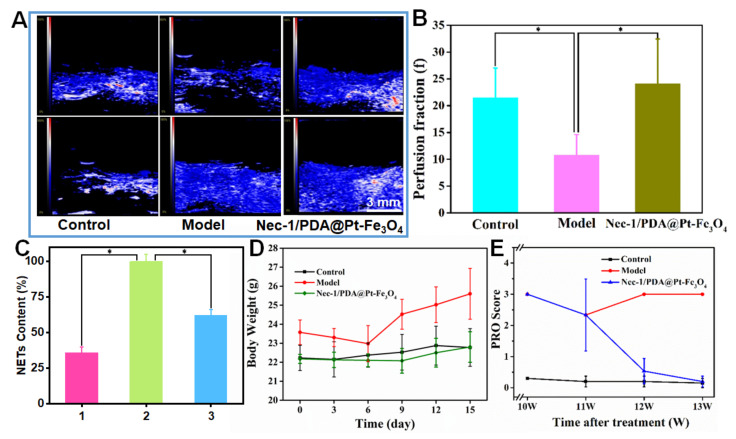

3.3. Therapeutic Effect of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 on LN

Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 showed considerable therapeutic quality apart from acting as a dual-mode imaging contrast agent. PDA, as the main material of this nanocomposite, is a good free radical scavenger because of its rich phenolic groups, which eliminates the ROS produced in inflammatory reactions [21]. Pt has a high catalase catalytic activity and can thus catalyze hydrogen peroxide and produce oxygen gas, which significantly improves the hypoxia microenvironment of LN and alleviate LN to a certain extent [35]. To intuitively confirm the change in oxygen level in the kidney area, we carried out a blood oxygen graph of mouse photoacoustic tomography. As shown in Figure 4A, the closer the color level is to 100%, the higher the blood oxygen saturation (SaO2) is. The results demonstrated that the SaO2 level of the model group greatly decreased relative to that in the control group, indicating that inflammation reduced the oxygen content. After the addition of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, the SaO2 level in the kidney considerably increased relative to that in the model group and was equal to the SaO2 level of the control. These results showed that improving the anoxic microenvironment has a certain therapeutic effect on LN. Moreover, iVIM-DWI sequence renal perfusion scores among the control, model, and drug group were compared (Figure 4B). The results demonstrated that the renal perfusion score of the mice in the model group was lower than that in the control group, indicating that the renal capillaries in the model group mice were damaged. After the injection of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, the renal perfusion score of mice significantly increased, and the renal capillaries damage was reduced. This result demonstrated that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 decreased inflammation in the kidney and alleviated LN.

Figure 4.

(A) Blood oxygen graph of mouse photoacoustic tomography. (B) Comparison of iVIM-DWI sequence renal perfusion scores in different groups of mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. * p < 0.05 vs. the model group. (C) The percentage content of NETs released by a neutrophil. 1 represents neutrophil control group; 2 represents neutrophil + PMA; 3 represents neutrophil + PMA + Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. * p < 0.05 vs. the neutrophil + PMA group. (D) Body weight and (E) PRO content change before and after Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 treatment.

Nec-1 is an inhibitor of receptor-interacting protein 1 kinase, which inhibits RIPK1 kinase activity and reduces LN inflammation [36,37]. As shown in Figure 4C, PMA can promote NET production. After the addition of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, the NET content decreased to 50%, which demonstrated that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 loading Nec-1 had excellent performance in inhibiting RIPK1 kinase activity and reduced NET production by RIPK1. Body weight change in the mice was recorded in the entire experiment. The result showed that the body weight of LN mice (model group) exhibited decreased and then increased. The possible principal reason for this trend was the production of ascites when LN was aggravated. In the control and drug groups, the body weights of the mice were basically stable, suggesting that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 can treat LN to some extent (Figure 4D). Furthermore, we measured the urinary protein content. As shown in Figure 4E, the urine protein content of the control group mice remained low, and the urine protein content in the model group mice remained high. After treatment with Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4, the content of urinary protein gradually reduced with the extension of treatment time, demonstrating that the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 improved renal function.

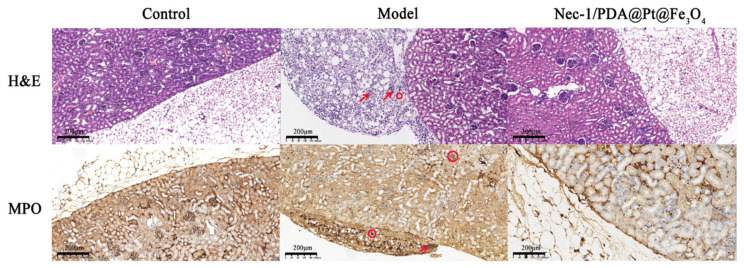

To further test the therapeutic efficacy of the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 for LN, we performed a pathological examination on the kidneys of the mice. The kidneys were sectioned and stained with H&E and MPO. As shown in Figure 5, H&E staining showed numerous neutrophils and lymphocytes that infiltrated the renal cortex, indicating severe kidney inflammation. In the control and drug groups, clear infiltration around the renal cortex without inflammatory cell infiltration was observed, demonstrating that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 reduced inflammation and then ameliorated LN. MPO staining showed similar results. Neutrophils and some lymphocytes were observed around the renal cortex in the model group. In the control and drug groups, neutrophils and some lymphocytes around the renal cortex markedly decreased, showing that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 can reduce inflammation. In general, these results suggested that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 can ameliorate LN.

Figure 5.

H&E and MPO staining images of kidney sections. The area where the red arrow is pointing represents neutrophils. The red circle area represents lymphocytes.

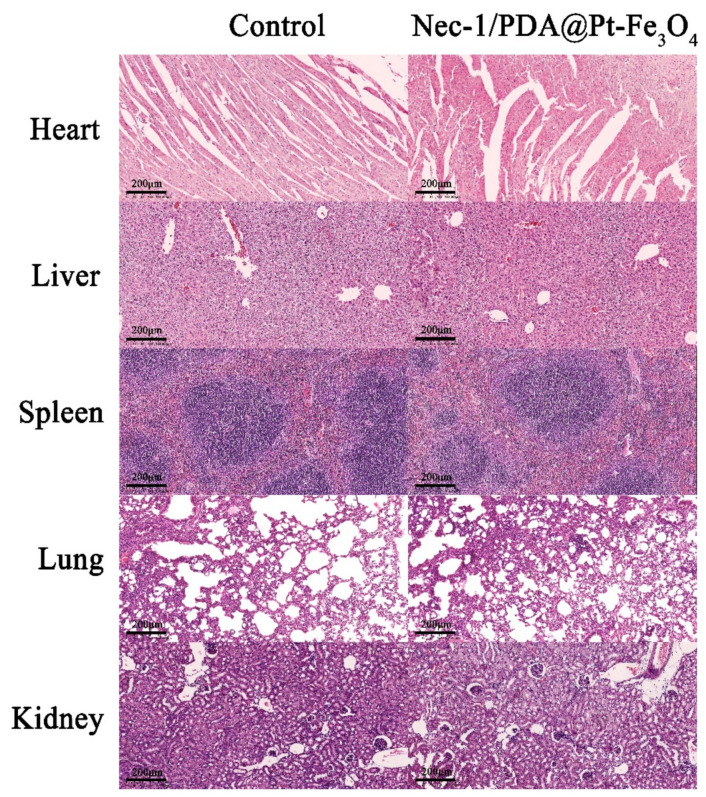

3.4. Biosafety Assessment of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4

To further investigate the potential for clinical applications, we studied the biosafety of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 in vivo and performed H&E staining on vital organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidney). The results showed no apparent abnormality or damage of mouse vital organs in the histopathological experiment after the mice were treated with Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 (Figure 6), indicating that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 has low toxicity in vivo. Hence, Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 may be used clinically for LN treatment.

Figure 6.

Biosafety and toxicity in vivo. Histological toxicity evaluation of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4. Organs mainly include the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidney.

4. Conclusions

A multifunctional photoacoustic/magnetic resonance dual-mode-imaging nanocarrier loading Nec-1 was reported for the diagnosis and therapy of LN. This nanocarrier (Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4) consisted of a PDA-based nanocarrier modified with Fe3O4 and platinum nanoparticles and Nec-1. Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 are regarded as safe, and we did not observe any toxicities in mice after they received the nanocarrier. The blood oxygen graph of mouse photoacoustic tomography confirmed that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 can generate oxygen to fight against the hypoxic microenvironment of LN. Cellular experiments and in vivo tests in the LN mice model confirmed that the nanocarrier can inhibit RIPK1 kinase activity and reduce NET production by RIPK1. After three weeks of systemic administration, the Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 prominently alleviated the progression of inflammation in the LN mice model. Additionally, the preliminary imaging results confirmed that Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 can exhibit strong PA signal intensity and a negative enhancement of T2-weighted signal intensity, supporting its potential for photoacoustic/magnetic resonance dual-mode imaging, which can monitor accurately and non-invasively the progression of LN. Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 combining these benefits exhibited excellent performance in LN diagnosis and therapy. Therefore, Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 is a promising nanocarrier system for dual-mode imaging and LN therapy. Last, it remains to be explored the full extent of Nec-1/PDA@Pt-Fe3O4 efficacy in LN mouse models, including, but not limited to, survival analysis, dose-dependent response, the presence of side effects, and the study of the mechanisms involved. We propose that the results from this study establish the translational potential of humans, but further studies should be conducted to prove this hypothesis.

Abbreviations

PDA: polydopamine; Pt: platinum; Fe3O4: ferroferric oxide; Nec-1: necrostatin-1; LN: lupus nephritis; PMA: Phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate; RIPK1: receptor interacting protein kinase 1; NETs: neutrophil extracellular traps; ROS: reactive oxygen species; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PA: photoacoustic imaging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and L.Z.; Data curation, M.L., Y.L. and M.M.; Formal analysis, M.L. and Y.W.; Funding acquisition, L.Z.; Methodology, X.H.; Project administration, L.Z.; Resources, X.H., Y.L. and L.Z.; Supervision, L.Z.; Visualization, M.L., Y.W. and X.H.; Writing—original draft, M.L. and Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, Y.L. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Committee of Shenzhen ENT Institute approved all animal procedures, which were following the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (No. 20210284).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Bureau of Science and Technology Innovation of Longgang District (Grants No: LGKCYLWS2021000004), the Bureau of Science and Technology Innovation of Longgang District (Grants No: LGWJ2021-25), and the Foundation for Basic and Applied Basic Research of Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation Projects (Grants No: 2022A1515011095).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Anders H.-J., Saxena R., Zhao M.-H., Parodis I., Salmon J.E., Mohan C. Lupus nephritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maroz N., Segal M.S. Lupus Nephritis and End-stage Kidney Disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013;346:319–323. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31827f4ee3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moroni G., Ponticelli C. The multifaceted aspects of refractory lupus nephritis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2015;11:281–288. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.990883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anders H.-J., Hiepe F. Treatment Options for Refractory Lupus Nephritis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019;14:653–655. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03230319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin L., Liu P., Yin M., Zhang M., Kuang Y., Zhu W. RIPK1: A rising star in inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2020;99:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mifflin L., Ofengeim D., Yuan J. Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) as a therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:553–571. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0071-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pieterse E., Rother N., Garsen M., Hofstra J.M., Satchell S.C., Hoffmann M., Loeven M.A., Knaapen H.K., van der Heijden O.W.H., Berden J.H.M., et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Drive Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017;37:1371–1379. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurata Y., Tanaka T., Nangaku M. The role of hypoxia in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2020;98:821–823. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M., Ishikawa T., Lai Y., Nallapothula D., Singh R.R. Diverse Roles of NETosis in the Pathogenesis of Lupus. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:895216. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.895216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke J. NETs directly injure cartilage in RA. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020;16:410. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frangou E., Vassilopoulos D., Boletis J., Boumpas D.T. An emerging role of neutrophils and NETosis in chronic inflammation and fibrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV): Implications for the pathogenesis and treatment. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019;18:751–760. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han X.A., Jie H.Y., Wang J.H., Zhang X.M., Wang J., Yu C.X., Zhang J.L., He J., Chen J.Q., Lai K.F., et al. Necrostatin-1 Ameliorates Neutrophilic Inflammation in Asthma by Suppressing MLKL Phosphorylation to Inhibiting NETs Release. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:666. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McHugh J. Targeted delivery of immunosuppressant in SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020;16:410. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddique S., Chow J.C.L. Recent Advances in Functionalized Nanoparticles in Cancer Theranostics. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:2826. doi: 10.3390/nano12162826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siddique S., Chow J.C.L. Application of Nanomaterials in Biomedical Imaging and Cancer Therapy. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1700. doi: 10.3390/nano10091700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J., Chen C., Fu H., Yu J., Sun Y., Huang H., Tang Y., Shen N., Duan Y. MicroRNA-125a-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles Alleviate Systemic Lupus Erythematosus by Restoring Effector/Regulatory T Cells Balance. ACS Nano. 2020;14:4414–4429. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b09998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z., Zou Y., Li Y., Cheng Y. Metal-Containing Polydopamine Nanomaterials: Catalysis, Energy, and Theranostics. Small. 2020;16:1907042. doi: 10.1002/smll.201907042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu J.H., Messersmith P.B., Lee H. Polydopamine Surface Chemistry: A Decade of Discovery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:7523–7540. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b19865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H., Zeng Z., Liu L., Chen J., Zhou H., Huang L., Huang J., Hu X., Xu Y., Chen Z., et al. Polydopamine nanoparticles for the treatment of acute inflammation-induced injury. Nanoscale. 2018;10:6981–6991. doi: 10.1039/C8NR00838H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding F., Gao X., Huang X., Ge H., Xie M., Qian J., Song J., Li Y., Zhu X., Zhang C. Polydopamine-coated nucleic acid nanogel for siRNA-mediated low-temperature photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 2020;245:119976. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y., Wang Y., Chen Z., Cai J., Li K., Huang H., Song F., Gao M., Yang Y., Zheng L., et al. NIR-driven polydopamine based nanoenzymes as ROS scavengers to suppress osteoarthritis progression. Mater. Today Nano. 2022;19:100240. doi: 10.1016/j.mtnano.2022.100240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma W., Zhang X., Liu Y., Fan L., Gan J., Liu W., Zhao Y., Sun L. Polydopamine Decorated Microneedles with Fe-MSC-Derived Nanovesicles Encapsulation for Wound Healing. Adv. Sci. 2022;9:2103317. doi: 10.1002/advs.202103317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie L., Pang X., Yan X., Dai Q., Lin H., Ye J., Cheng Y., Zhao Q., Ma X., Zhang X., et al. Photoacoustic Imaging-Trackable Magnetic Microswimmers for Pathogenic Bacterial Infection Treatment. ACS Nano. 2020;14:2880–2893. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b06731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y., Wang K., Zhao S., Xiong Q., Liu G., Li Y., Fang Q., Gong X., Xuan S. Rough surface NiFe2O4@Au/Polydopamine with a magnetic field enhanced photothermal antibacterial effect. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;437:135282. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.135282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H., Deng L., Liu H., Mai S., Cheng Z., Shi G., Zeng H., Wu Z. Enhanced fluorescence/magnetic resonance dual imaging and gene therapy of liver cancer using cationized amylose nanoprobe. Mater. Today Bio. 2022;13:100220. doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segers F.M.E., Ruder A.V., Westra M.M., Lammers T., Dadfar S.M., Roemhild K., Lam T.S. Magnetic resonance imaging contrast-enhancement with superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles amplifies macrophage foam cell apoptosis in human and murine atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022:1–14. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvac032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sargsyan S.A., Serkova N.J., Renner B., Hasebroock K.M., Larsen B., Stoldt C., McFann K., Pickering M.C., Thurman J.M. Detection of glomerular complement C3 fragments by magnetic resonance imaging in murine lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2012;81:152–159. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang S., Liu B., Xiao X., Yuan M., Yang L., Ma P.A., Cheng Z., Lin J. A Robust Narrow Bandgap Vanadium Tetrasulfide Sonosensitizer Optimized by Charge Separation Engineering for Enhanced Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2021;33:2101467. doi: 10.1002/adma.202101467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L., Li M., Zhou Q., Dang M., Tang Y., Wang S., Fu J., Teng Z., Lu G. Computed tomography and photoacoustic imaging guided photodynamic therapy against breast cancer based on mesoporous platinum with insitu oxygen generation ability. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10:1719–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T., Liu Y., Zhou J., Lin L., Jia C., Wang J., Yu L., Wang Y., Yan Z. Controllable hydrogen release for gas-assisted chemotherapy and ultrasonic imaging of drug-resistant tumors. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;421:129917. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.129917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bian S.W., Liu S., Chang L. Synthesis of magnetically recyclable Fe3O4@polydopamine–Pt composites and their application in hydrogenation reactions. J. Mater. Sci. 2016;51:3643–3649. doi: 10.1007/s10853-015-9688-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y., Liu X., Deng G., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang Q., Lu J. Multifunctional PS@CS@Au-Fe3O4-FA nanocomposites for CT, MR and fluorescence imaging guided targeted-photothermal therapy of cancer cells. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:4221–4232. doi: 10.1039/C7TB00642J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dema B., Lamri Y., Pellefigues C., Pacreau E., Saidoune F., Bidault C., Karasuyama H., Sacré K., Daugaus E., Charles N. Basophils contribute to pristane-induced Lupus-like nephritis model. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7969. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08516-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pravda J. Hydrogen peroxide and disease: Towards a unified system of pathogenesis and therapeutics. Mol. Med. 2020;26:41. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00165-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gutiérrez de la Rosa S.Y., Muñiz Diaz R., Villalobos Gutiérrez P.T., Patakfalvi R., Gutiérrez Coronado Ó. Functionalized Platinum Nanoparticles with Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:9404. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jie H., He Y., Huang X., Zhou Q., Han Y., Li X., Bai Y., Sun E. Necrostatin-1 enhances the resolution of inflammation by specifically inducing neutrophil apoptosis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:19367–19381. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu B.F., Gong Q., Chen S.Q., Yue L., Ma W.X., Wang F., Feng X.-W., Wang J.-N., Li C., Liu M.-M., et al. Protective effect of inhibiting necroptosis on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity. FASEB J. 2022;36:e22487. doi: 10.1096/fj.202200163R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.