Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy and tolerability of omega-3 fatty acids (FAs) and inositol alone and in combination for the treatment of pediatric bipolar (BP) spectrum disorder in young children.

Methods

Participants were male and female children ages 5–12 meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a BP spectrum disorder and displaying mixed, manic, or hypomanic symptoms without psychotic features at the time of evaluation.

Results

Participants concomitantly taking psychotropic medication were excluded from efficacy analyses. There were significant reductions in YMRS and HDRS mean scores in the inositol and combination treatment groups (all p < 0.05) and in CDRS mean scores in the combination treatment group (p < 0.001), with the largest changes seen in the combination group. Those receiving the combination treatment had the highest rates of antimanic and antidepressant response. The odds ratios for the combination group compared to the omega-3 FAs and inositol groups were clinically meaningful (ORs ≥2) for 50% improvement on the YMRS, normalization of the YMRS (score <12) (vs. inositol group only), 50% improvement on the HDRS, 50% improvement on CDRS (vs. omega-3 FAs group only), and CGI-I Mania, CGI-I MDD, and CGI-I Anxiety scores <2.

Conclusion

The antimanic and antidepressant effects of the combination treatment of omega-3 FAs and inositol were consistently superior to either treatment used alone. This combination may offer a safe and effective alternative or augmenting treatment for youth with BP spectrum disorder, but more work is needed to confirm the statistical significance of this finding.

Keywords: psychopharmacology, pediatric, pediatric bipolar, natural supplements

Introduction

Pediatric bipolar (BP) disorder is a prevalent and highly morbid disorder representing a serious public health concern.1–4 Children with BP disorder often exhibit high levels of severe irritability and concurrent features of mania and depression, as well as high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, complicating their diagnosis and treatment. Due to the severity of their symptoms of mania and depression and comorbid conditions, these children often require psychiatric hospitalizations.5–8 Although there are several medications that are U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the treatment of pediatric BP disorder down to age 10, they can be associated with annoying and serious adverse effects including weight gain, dyslipidemia, glycemic dyscontrol, and risk for tardive dyskinesia, calling for the identification of safe and effective alternative treatments.9–11

Natural products such as omega-3 fatty acids (FAs), a concentrated source of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and inositol may provide such an alternative. Omega-3 FAs increase membrane fluidity, optimizing neurochemical receptor functioning12,13 and inositol works as a critical second messenger in cellular processes.14–19 As such, their mechanisms are complementary, and the combination may have an additive effect in the treatment of pediatric BP disorder.

Omega-3 FAs have been shown to reduce both depressive20–23 and manic symptoms23–25 in children and adults, are safe and well tolerated, and have been used successfully for the commonly comorbid condition of ADHD in children.13 Inositol is involved in the second messenger system for processes known to be involved in the pathophysiology of mood disorders and has evidence supporting its use from clinical trials and imaging studies.14–16 Myo-inositol has been shown to be decreased in the cerebrospinal fluid of adult patients with depression.26

Spectroscopic study has revealed myo-inositol abnormalities in children with BP disorder that were corrected following lithium therapy.27,53 Randomized, placebo-controlled trials have shown trends for superior efficacy of inositol compared to placebo for depressive symptoms.28 Few of these studies included pediatric participants and no study addressed pre-adolescent children only. In a preliminary mid-point pilot report, our group previously showed that the combination treatment of omega-3 FAs plus inositol reduced manic, depressive, and overall psychiatric symptoms to a greater degree than either treatment alone and that both natural products were safe and well-tolerated.29

We are now reporting on our final sample and limiting the analysis to participants taking only the study treatments and no concomitant mood-stabilizing medications.

The main aim of the current study was to assess the efficacy and tolerability of omega-3 FAs and inositol both alone and in combination for the treatment of pediatric BP spectrum disorder in younger children. To this end, we completed a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in children 5–12 years of age with BP spectrum disorder. For this analysis, we excluded subjects taking other psychotropic medication, so that results reflect the monotherapy use of these complementary and alternative treatments used alone and in combination. We hypothesized that, consistent with the findings of our preliminary analysis, omega-3 FAs and inositol in combination would be more effective than either supplement alone in the treatment of pediatric BP spectrum disorder and would be well-tolerated.

Methods

Participants

Participants were male and female children ages 5–12 meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a BP spectrum disorder (type I, type II, or not otherwise specified) and displaying mixed, manic, or hypomanic symptoms without psychotic features at the time of evaluation.

All diagnoses were established by clinical interviews of the children and their parents or guardians by an expert clinician, supported by the mood modules of the Kiddie Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Epidemiological Version (K-SADS-E).30,31 BP I disorder was defined according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a manic episode, requiring participants to meet criterion A for a distinct period of extreme and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood lasting at least one week as well as criterion B, manifested by three (four if the mood is irritable only) of seven symptoms during the period of mood disturbance. BP II disorder was defined according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for hypomania (an abnormal mood lasting at least 4 days). BP disorder not otherwise specified was defined as a severe manic mood disturbance that either did not meet DSM-IV duration criteria for hypomania or had fewer symptoms than required in criterion B (two symptoms required for elation and three for irritability). A diagnosis of psychosis was established by the presence of hallucinations or delusions on the structured diagnostic interview.

Eligible participants were required to have a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)32,33 total score ≥20 and ≤40 at baseline assessment, and participants with a diagnosis of psychosis or a score of 8 (“delusions; hallucinations”) on YMRS item 8 (content) were excluded from the study, as a safety measure required by our IRB. All assessments were completed by board-certified or board-eligible child and adolescent psychiatrists trained to a high level of interrater reliability. The intraclass correlation score for interrater reliability on the YMRS was 0.81.52

Participants with any serious or unstable medical illness were excluded. Those with a history of sensitivity or intolerance to omega-3 FAs or inositol, severe allergies, or multiple adverse drug reactions were also excluded from the study. Participants with an estimated full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) <70 were excluded. No child that was adequately stabilized on antimanic therapy or had failed ≥2 previous trials with antimanic treatments including lithium, anticonvulsants, or atypical antipsychotic medication was entered into the study. Finally, we excluded participants judged clinically to be at serious suicidal risk, with a current diagnosis of schizophrenia, with a current or past history of seizures, who had begun menstruation, or who had active substance use, abuse, or dependence.

No participants were tapered off their medications to be included in this study, although, per protocol, only participants with a poor response to their current medication treatment would be advised to consider a taper off their medications for entry into the study. Concomitant psychotropic medications were allowed in this study as long as the participant’s treatment regimen remained the same throughout the entire study and had been stable for at least one month prior to study entry. However, since the vast majority of participants were not taking any concomitant medication treatments, for the efficacy analyses of the study treatment, we excluded five subjects who were taking concomitant psychotropic treatment. Non-pharmacological treatments such as individual, family, or group therapy were allowed if they were in place before the participant joined the study. The participant’s therapy regimen was required to remain the same throughout the study. No new pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatments were to be initiated after study participation had begun. The use of the benzodiazepine lorazepam was permitted during the study at a maximum dosage of 2mg per day for maximum of three days during the study. Any greater need for lorazepam was considered evidence of poor treatment response and grounds for termination of the study.

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the committee for human subjects at our institution. All participants’ parents or guardians signed written informed consent forms and participants ages 7 years or older signed written assent forms. The trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01396486).

Study Design

Participants were randomized in double-blind fashion into one of three treatment arms: inositol + placebo, omega-3 FAs + placebo, or inositol + omega-3 FAs.

Inositol and inositol placebo capsules were created by the Massachusetts General Hospital Clinical Trials pharmacy, and inositol powder was provided by Life Extension. Inositol capsules contained 500mg inositol powder each and placebo capsules contained 500mg lactose powder each and were polished using muslin or cheesecloth with a small amount of light mineral oil. Participants weighing ≥25kg were dosed at 2,000mg (4 500mg capsules) of inositol or placebo daily. Participants weighing <25kg were dosed at 80mg per kg rounded down to the nearest 500mg capsule. These doses were maintained for the duration of the trial and were allowed to be separated into two daily doses.

Omega-3 FAs were provided in the form of Nordic Naturals brand high EPA omega-3 fatty acid soft gels (325mg EPA and 225mg DHA per 2 capsules). Nordic Naturals also provided the omega-3 fatty acid placebo. The placebo soft gels contained 500mg soybean oil each and had the same strawberry flavoring as the active omega-3 soft gels. A small amount of omega-3 FAs (approximately 55mg, with 1.9mg EPA) was added to the omega-3 placebo soft gels to provide a slightly fishy taste. All participants were dosed at 975mg EPA daily, with 6 of the soft gel capsules, which was 1650mg combined EPA+DHA total daily dose, or 6 matched placebo capsules, daily. This dose was maintained for the duration of the trial and was allowed to be separated into two daily doses.

Study clinicians assessed safety and efficacy of the study treatment at weekly intervals via office or phone visits. Participants were asked to return unused capsules and soft gels at each office visit. Study medication was counted by study staff at every office visit to ensure compliance and participants who failed to keep study appointments or were non-compliant with treatment were discontinued from study. Adverse events and concomitant medications were monitored weekly.

Clinician-Rated Assessment Scales

Severity of manic and depressive symptoms were assessed weekly using the YMRS, the Children’s Depression Rating Scale (CDRS),35 and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS).36 Global functioning was assessed weekly using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF).37 Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and psychotic symptoms were evaluated at baseline, midpoint, and endpoint with the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS)38 and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),39 respectively. To determine clinically significant severity and improvement relative to baseline, the NIMH Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity (CGI-S) and improvement (CGI-I) scales40 were completed weekly. CGI-S and CGI-I were assessed separately for mania, depression, anxiety, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and overall BPD.

At study beginning, participants completed a brief cognitive screen, as any participant with an estimated IQ below 70 was not eligible to participate in the study. The scales we used meet the demand for quick reliable measures of intelligence in clinical, educational and research settings. These tests provided estimates of verbal and nonverbal ability respectively, as well as the direct measure of Full Scale IQ. Depending upon the subject’s age, the cognitive screen consisted of: for participants age 5 years—Verbal Knowledge, Riddles, and Matrices subtests of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT-2)41 and for participants ages 6–12 years—Vocabulary and Matrices subtests of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI).42

Safety Assessment

Safety was assessed at each visit using spontaneous reports of treatment-emergent adverse events. Changes in vital signs (blood pressure, temperature, height, and weight) were recorded at every office visit.

The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)43 was administered weekly by a study clinician to assess initial and emergent suicidality in participants. Participants with scores of 4 or higher on the C-SSRS were discontinued from the study.

Definition of Clinical Response

Response was defined as having either a ≥30% reduction in symptoms according to the YMRS, HDRS, or CDRS at endpoint or by a rating of “much improved” or “very much improved” (score ≤2) on the CGI-I for mania or depression. We also assessed the percentage of participants who had a ≥50% reduction in symptoms according to the YMRS, HDRS, or CDRS at endpoint and the percentage of participants who had a score <12 on the YMRS at endpoint.

Poor response to treatment was defined by a CGI-S score for overall BP disorder 2 points higher (more severe) than baseline for 2 weeks in a row or a YMRS score 30% higher than baseline for 2 weeks in a row, which was grounds for discontinuation from the study as determined by the study clinician. Participants with individual YMRS item scores of 8 on item 8 (content) or greater than 6 on item 9 (disruptive/aggressive behavior) for 2 weeks in a row were also discontinued from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous outcome measures and vital signs were analyzed using mixed-effects Poisson regression models and mixed-effects linear regression models, respectively, with time as the predictor for within group analyses and time, treatment group, and the time-by-treatment group interaction as the predictors for between group analyses. All mixed-effects models used robust standard errors to account for the repeated measures on each participant. Rates of response at endpoint were analyzed using logistic or exact logistic regression models. The number of adverse events reported was analyzed using a negative binomial regression model and the proportions of participants reporting adverse events were analyzed with Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Tests were two-tailed and performed at the 0.05 alpha level using Stata (Version 16.0).44 All analyses were intention-to-treat (ITT).

Descriptive statistics are reported as absolute numbers, percentages, or mean ± standard deviation (SD) and use last observation carried forward (LOCF) for participants who did not complete the 12 weeks. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated as Cohen’s d comparing baseline and endpoint assessments for within group analyses and comparing the change in scores from baseline to endpoint for between group analyses. For within group analyses, a positive SMD indicates an improvement from baseline to endpoint. For between group analyses, a positive SMD indicates that the first group being compared performed better than the second group being compared. As defined by Cohen,45 a SMD = 0.2 is interpreted as a small effect size, SMD = 0.5 as medium, and SMD = 0.8 as large. Odds ratios (ORs) were reported for dichotomous outcomes. In the event of zero cells, 0.5 was added to all cells to calculate the odds ratio.

Results

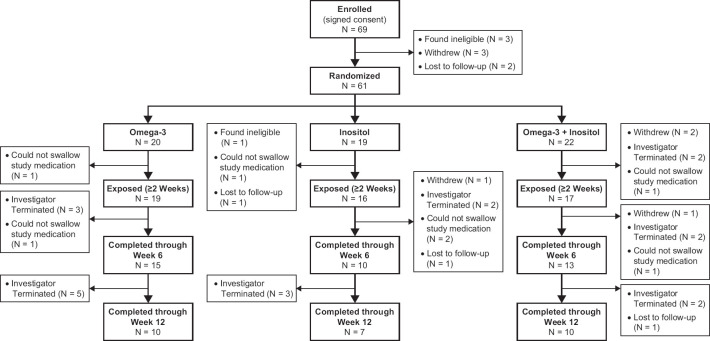

As shown in Figure 1, 69 participants signed consent and enrolled in the trial. Of these, 61 were randomized to receive either omega-3 FAs (N = 20), inositol (N = 19), or the combination treatment (omega-3 FAs + inositol) (N = 22). Fifty-two were exposed to the treatment (i.e. ≥2 weeks) and 27 completed the 12-week study (n = 10 omega-3 FAs, n = 7 inositol, n = 10 combination). Reasons for not completing the study included the following: lack of efficacy (n = 15), participant could not swallow the study medication (n = 7), non-compliant with the study procedures (n = 2), poor response to treatment (n = 1), need for more aggressive treatment (n = 1), ineligible after enrolled (n = 1), participant withdrew (n = 4), and lost to follow-up (n = 3).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

We analyzed 47 of the 52 participants who were exposed to treatment for at least two weeks for efficacy. Five participants were excluded from the efficacy analyses because they were taking adjunct mood stabilizing medications throughout the trial. Two participants in the omega-3 FAs group reported taking aripiprazole and risperidone, two participants in the inositol group reported taking risperidone, chlorpromazine, and lurasidone, and one participant in the combination group reported taking sertraline and hydroxyzine. Thus, our final groups for analysis included 17 participants in the omega-3 FAs group, 14 participants in the inositol group, and 16 in the combination group. There were no significant differences between the groups in age (omega-3 FAs: 7.9 ± 1.6 years vs. inositol: 8.6 ± 2.4 years vs. combination: 8.2 ± 2.5 years; p = 0.69), full-scale IQ (omega-3 FAs: 99.5 ± 17.6 vs. inositol: 104.6 ± 14.7 vs. combination: 113.3 ± 21.5; p = 0.11), baseline YMRS (omega-3 FAs: 24.9 ± 6.7 vs. inositol: 25.4 ± 4.5 vs. combination: 23.9 ± 5.9; p = 0.77), baseline GAF (omega-3 FAs: 52.0 ± 2.9 vs. inositol: 51.4 ± 2.7 vs. combination: 52.6 ± 1.8; p = 0.47), proportion of male participants (omega-3 FAs: 59% [n = 10/17] vs. inositol: 71% [10/14] vs. combination: 50% [n = 8/16]; p = 0.49), or proportion of Caucasian participants (omega-3 FAs: 93% [n = 14/15] vs. inositol: 93% [n = 13/14] vs. combination: 94% [n = 15/16]; p = 1.00).

Antimanic Effects

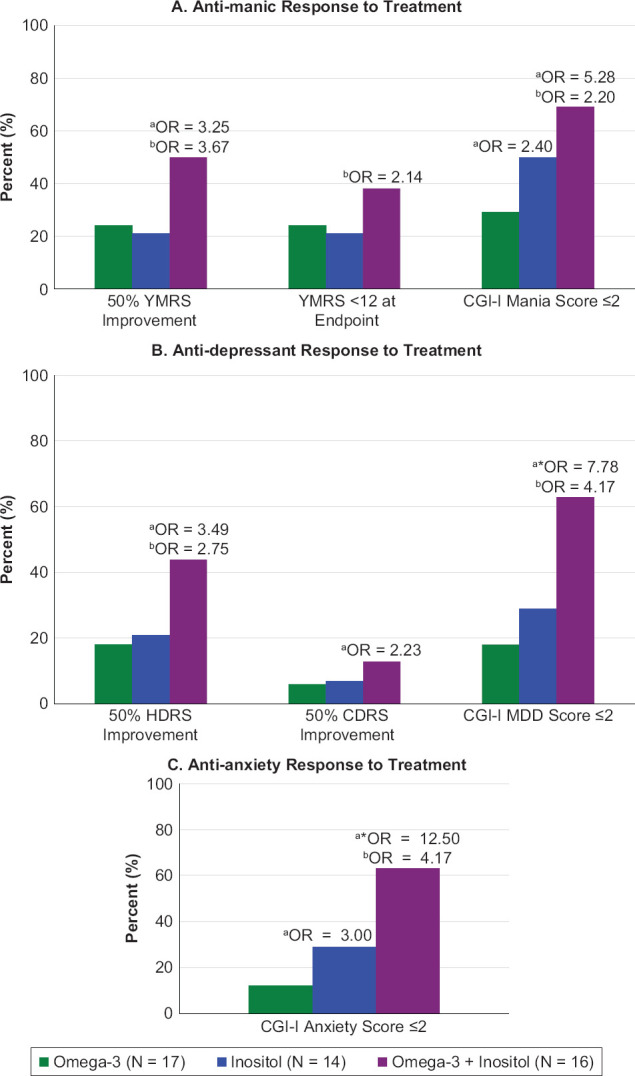

There were significant decreases in scores over time on the YMRS within the inositol and combination groups (both p < 0.001), with the largest change seen in the combination group (Table 1). The within group SMDs for all three groups were all medium to large. Those receiving the combination treatment also had the highest rates of response when examining those with 50% improvement on the YMRS, normalization on the YMRS (score <12), and CGI-I Mania scores ≤2 (Figure 2A). The omnibus tests for differences between the three groups were not significant (all p > 0.05), however the SMD for the combination group compared to the omega-3 FAs group and all but one of the ORs for the combination group compared to the omega-3 FAs and inositol groups were clinically meaningful (SMDs ≥0.04, ORs ≥2) (Table 1, Figure 2A). Additionally, the OR for the inositol group compared to the omega-3 FAs group was clinically meaningful for CGI-I Mania scores ≤2 (Figure 2A).

Table 1. Change in Score from Baseline to Endpoint in Measures of Mania, Depression, ADHD, and General Psychopathology.

| Measure | N | Baseline Score |

Endpoint Score† |

Difference | Within Group | Between Group | |||

| Effect Size | P-value | Effect Size | P-value | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | SMD (95% CI) | SMD (95% CI) | |||||

| Vs. Omega-3 | Vs. Inositol | ||||||||

| YMRS | 0.16 | ||||||||

| Omega-3 | 17 | 24.9 ± 6.7 | 20.7 ± 11.1 | −4.2 ± 8.1 | 0.52 (0.01, 1.03) | 0.07 | – | – | |

| Inositol | 14 | 25.4 ± 4.5 | 18.6 ± 8.3 | −6.9 ± 6.7 | 1.03 (0.38, 1.68) | <0.001 | 0.35 (−0.37, 1.06) | – | |

| Omega-3 + Inositol | 16 | 23.9 ± 5.9 | 14.4 ± 10.8 | −9.6 ± 8.9 | 1.07 (0.46, 1.68) | <0.001 | 0.62 (−0.08, 1.32) | 0.34 (−0.39, 1.06) | |

| HDRS | 0.14 | ||||||||

| Omega-3 | 17 | 15.8 ± 5.2 | 12.5 ± 6.4 | −3.4 ± 8.5 | 0.39 (−0.10, 0.88) | 0.05 | – | – | |

| Inositol | 14 | 18.6 ± 9.0 | 15.1 ± 8.3 | −3.5 ± 8.9 | 0.39 (−0.15, 0.93) | 0.03 | 0.02 (−0.69, 0.72) | – | |

| Omega-3 + Inositol | 16 | 17.1 ± 7.6 | 8.1 ± 3.9 | −8.9 ± 8.7 | 1.03 (0.42, 1.64) | <0.001 | 0.65 (−0.06, 1.35) | 0.62 (−0.12, 1.35) | |

| CDRS | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Omega-3 | 17 | 39.1 ± 9.1 | 35.2 ± 11.1 | −3.9 ± 10.7 | 0.36 (−0.13, 0.85) | 0.18 | – | – | |

| Inositol | 14 | 42.3 ± 10.8 | 36.5 ± 11.4 | −5.8 ± 10.6 | 0.55 (−0.01, 1.11) | 0.06 | 0.18 (−0.53, 0.89) | – | |

| Omega-3 + Inositol | 16 | 39.4 ± 7.6 | 28.4 ± 6.8 | −11.1 ± 7.6 | 1.46 (0.76, 2.16) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.05, 1.47)* | 0.58 (−0.16, 1.31) | |

| BPRS ‡ | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Omega-3 | 15 | 46.7 ± 9.9 | 37.9 ± 12.2 | −8.8 ± 11.3 | 0.78 (0.20, 1.36) | 0.002 | – | – | |

| Inositol | 13 | 48.8 ± 13.0 | 44.1 ± 12.2 | −4.8 ± 12.0 | 0.40 (−0.16, 0.96) | 0.001 | −0.35 (−1.09, 0.41) | ||

| Omega-3 + Inositol | 14 | 47.1 ± 8.3 | 32.9 ± 7.9 | −14.2 ± 11.3 | 1.26 (0.56, 1.96) | <0.001 | 0.48 (−0.26, 1.22) | 0.81 (0.02, 1.59)* | |

| ADHD RS ‡ | 0.45 | ||||||||

| Omega-3 | 15 | 39.1 ± 13.7 | 30.9 ± 14.2 | −8.2 ± 10.1 | 0.81 (0.23, 1.39) | 0.001 | – | – | |

| Inositol | 13 | 37.8 ± 15.1 | 32.4 ± 12.2 | −5.4 ± 11.3 | 0.47 (−0.10, 1.04) | 0.02 | −0.26 (−1.01, 0.49) | – | |

| Omega-3 + Inositol | 14 | 32.6 ± 15.4 | 30.7 ± 16.9 | −1.9 ± 13.7 | 0.14 (−0.39, 0.67) | 0.45 | −0.52 (−1.26, 0.22) | −0.27 (−1.03, 0.49) | |

† Endpoint score uses last observation carried forward for those who dropped prior to week 12.

‡ Subjects were excluded from analysis if they were missing baseline data (N = 1) or did not have any follow-up data (N = 4).

*P < 0.05. Bolded values indicate clinically meaningful SMDs defined as ⩾0.40.

Figure 2.

Response to Treatment

a Odds Ratio (OR) vs. Omega-3. b OR vs. Inositol. *P < 0.05.

P > 0.05 for all omnibus tests except CGI-I MDD (p = 0.03) and CGI-I Anxiety (p = 0.02).

Antidepressant Effects

The inositol and combination groups had significant decreases in scores on the HDRS (both p < 0.05) and the combination group had a significant decrease in scores on the CDRS (p < 0.001), with the largest changes seen in the combination group (Table 1). The within group SMDs for these two groups and outcomes were medium to large. Those receiving the combination treatment also had the highest rates of response when examining those with 50% improvement on the HDRS and CDRS as well as CGI-I MDD scores ≤2 (Figure 2B). The omnibus tests for differences between the groups were significant when looking at improvement on the CDRS and rates of CGI-I MDD scores ≤2 (both p = 0.03). Pairwise analyses revealed that those in the combination group improved significantly more on the CDRS and were significantly more likely to have CGI-I MDD scores ≤2 compared to those in the omega-3 FAs group. While the other omnibus tests were not significant, the SMDs and all but one of the ORs comparing the combination group to the other two groups were clinically meaningful (Table 1, Figure 2B).

Response in Other Domains

For general psychopathology, all three treatment groups had significant decreases in scores on the BPRS, with the largest change seen in the combination group (all p < 0.05) (Table 1). The within group SMDs were all medium to large. Further, those in the combination group had the highest rates of response when examining CGI-I Anxiety scores ≤2 (Figure 2C). The omnibus tests for the BPRS and CGI-I Anxiety were significant (both p < 0.05). Pairwise analyses revealed that BPRS scores of those in the combination group improved significantly more than those in the inositol group and those in the combination group had significantly higher rates of participants with CGI-I Anxiety scores ≤2 compared to those in the omega-3 FAs group. While not significant, the SMDs and ORs comparing the combination group to the inositol group and to the omega-3 FA groups on the BPRS and CGI-I Anxiety, respectively, and the OR comparing the inositol group to the omega-3 FAs group on the CGI-I Anxiety were clinically meaningful. Improvement in ADHD was limited as demonstrated by the ADHD-RS (Table 1). Unlike the measures for mania, depression, and general psychology, the combination group had the smallest changes in ADHD-RS scores and the omega-3 FAs group had the largest changes.

Safety and Tolerability

While only those receiving study treatments who were exposed to treatment for ≥2 weeks and not receiving concomitant psychotropic medication were analyzed for efficacy, all participants who were randomized were included in the safety and tolerability analyses. Overall, 10 (50%) participants from the omega-3 FAs group, 12 (63%) participants from the inositol group, and 12 (55%) participants from the combination group dropped out of the study, but none were due to adverse events (see Figure 1 for reasons). These dropout rates did not statistically differ (p = 0.70). Treatments with omega-3 FAs and inositol were very well tolerated. Two serious adverse events were reported (aggressive behavior at school; agitation with a violent outburst requiring Emergency Room visit) and both were determined unlikely to be related to study treatment. One participant who was randomized to the combination group was dropped from the study at baseline and psychiatrically hospitalized due to exacerbation of preexisting symptoms of aggression and outbursts that were considered unrelated to the study treatment. The most commonly reported adverse event was nausea/vomit/diarrhea (Table 2). Treatment had no significant effects on blood pressure or pulse in the omega-3 FAs or combination groups (all p > 0.05). Treatment had no significant effects on systolic blood pressure or pulse for those in the inositol group but did have a significant effect on diastolic blood pressure with an average drop of 8.0 ± 10.2 points (baseline: 68.1 ± 13.9 vs. endpoint: 60.1 ± 12.9; p = 0.007). All three groups saw significant increases in weight from baseline to endpoint (omega-3 FAs: baseline = 70.3 ± 18.7 lbs vs. endpoint = 73.6 ± 19.8 lbs; inositol: baseline = 78.6 ± 28.6 lbs vs. endpoint = 81.1 ± 30.4 lbs; combination: baseline = 69.5 ± 22.1 lbs vs. endpoint = 71.8 ± 22.5 lbs; all p ≤ 0.005).

Table 2. Adverse Events in All Randomized Participants.

| Omega-3 | Inositol | Omega-3 + Inositol | ||

| N = 20 | N = 19 | N = 22 | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | P-Value | |

| Number (%) of Participants Reporting AEs | 14 (70) | 12 (63) | 10 (45) | 025 |

| Number (%) with Severe AEs | 2 (10) | 2 (11) | 2 (9) | 1.00 |

| Number (%) with Serious AEs | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.53 |

| AEs Reported ≥2 Times | ||||

| Nausea/Vomit/Diarrhea | 4 (20) | 1 (5) | 3 (14) | |

| Cold/Infection/Allergy | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | |

| Agitated/Irritable | 1 (5) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Headache | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | |

| Insomnia | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | |

| Sedation | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Tics | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| Mean Number of AEs Reported | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 2.7 | 4.5 ± 3.1 | 0.11 |

| Median (IQR) Number of AEs | 2.5 (1) | 1.5 (4.5) | 4 (4) |

Discussion

The results of this randomized, double-blind, controlled trial indicate that omega-3 FAs and inositol improved both manic and depressive symptoms after 12 weeks of treatment in pre- adolescent children with BP spectrum disorder who were not taking any concomitant psychotropic medication. Although concomitant medications were allowed per protocol, as the vast majority of the participants were only taking the study treatments (only 5 participants were taking concomitant medication), we excluded these participants from analysis to remove any possible positive effect from the concomitant medication. While all three groups demonstrated some improvement in symptoms of mania and depression, the effects of the combination treatment were consistently superior. To our knowledge, our results are the first to suggest that the combination treatment of two complementary and alternative treatments may be more effective than either treatment alone in the management of children with BP spectrum disorder, although more work with larger samples is needed to confirm the statistical significance of this finding.

The finding that the combination of omega 3-FAs plus inositol improved manic and depressive symptoms is consistent with our interim analysis of this study.29 Pediatric studies have supported the positive impact of omega-3 FAs on mood disorders, including our omega-3 FA pilot study.22–25 However, a recent review of complementary and alternative medicine performed a meta-analysis based on 4 placebo-controlled child and adolescent studies (N = 153) excluding bipolar disorder and concluded that EPA monotreatment provides no benefit for pediatric depression.54–55 A meta-analysis of adult studies of omega-3 PUFA found clinical benefit for depression.46 However, a very large prospective study of 18, 353 adults followed for 5–7 years randomized to Vitamin D and/or omega-3 fatty acids or matching placebo found no benefit from omega-3 FAs in preventing depression or boosting mood.47 The adult literature documents clinical benefits associated with inositol in adults with BP disorder,48–50 however, as with omega-3 FAs, meta-analyses are less encouraging. A meta-analysis of 7 inositol RCTs including 3 of BP depression (n = 242) reported no statistically significant effects of inositol on depressive symptoms.28 In contrast, 36-ingredient micronutrient supplement, EMPowerplus, (which includes inositol, but not omega-3 FAs) has preliminary evidence of potential benefit in a variety of mental disorders. A pediatric database analysis (N = 120) of children and adolescents using this supplement, without a control group, reported a 43% decline in pediatric BP symptoms and a 74% reduction in number of concomitant psychiatric medications.51 Taken together, these studies raise the question as to whether a combination of complementary and alternative interventions could be more effective than any one used alone.

In addition to the improvements in manic and depressive symptoms, all three treatment groups improved in symptoms of overall psychopathology and anxiety, with the combination group experiencing the greatest improvements in these domains. Given the high rates of comorbidity of pediatric BP spectrum disorder with other psychiatric conditions5–7 and the high levels of morbidity associated with these comorbidities,5 these additional improvements are relevant for the care of these highly impaired youth.

Omega-3 FAs and inositol were well-tolerated by the youth in this trial with a low frequency of adverse events among participants. Only one participant dropped from the study due to exacerbation of preexisting symptoms that were considered unrelated to the study treatment itself. Unexpectedly, all three treatment groups experienced similar weight gain during this 12-week study. Because we do not have a true placebo group, we cannot determine if the observed weight increases were related to the study treatments, but given the morbidity associated with weight gain, future studies tracking BMI are needed.

Strengths of this study include the double-blind design and the young 5–12-year age of participants. Additionally, no participant included in the efficacy analyses was taking concomitant antimanic or antidepressant medication beyond the study treatments. However, these results should be considered in the context of methodological limitations. Our findings may not be generalizable to the general population, as our sample consisted only of referred children. Additionally, since our study consisted largely of Caucasian children, our findings may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups. All children were age 12 or younger, and menstruation was an exclusionary criterion, but as this study did not include Tanner staging, we cannot call this a study of prepubertal children. Due to exclusion criteria, designed as a safety measure to exclude participants with severe illness who should be referred to FDA approved treatments, our results apply only to children with YMRS scores of 40 or lower. This trial was limited also by a long recruitment period and a high dropout rate, attributable in part to the long length of study (12 weeks) and that the treatments are safe and easily available for over-the-counter purchase.

Despite the high drop-out rate, only one participant was terminated for poor response to treatment. Future studies can benefit from a shorter length of study, a study design that is flexible and the use of telepsychiatry to make participation easier for children and parents. Despite these limitations, our results indicate that omega-3 FAs and inositol were well-tolerated in young school-aged youth and improved both manic and depressive symptoms, with the combination treatment group under double-blind conditions experiencing the largest improvements. If replicated in larger randomized and controlled trials, the combination of omega-3 FAs and inositol may offer a safe and effective alternative, or augmenting, treatment for youth with BP spectrum disorder.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Janet Wozniak receives research support from PCORI and Demarest Lloyd, Jr. Foundation. In the past, Dr. Wozniak has received research support, consultation fees or speaker’s fees from Eli Lilly, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, McNeil, Merck/Schering-Plough, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Pfizer, and Shire. She is the author of the book, “Is Your Child Bipolar” published May 2008, Bantam Books. Her spouse receives royalties from UpToDate; consultation fees from Emalex, Noctrix, Disc Medicine, Avadel, HALEO, OrbiMed, and CVS; and research support from Merck, NeuroMetrix, American Regent, NIH, NIMH, the RLS Foundation, and the Baszucki Brain Research Fund. In the past, he has received honoraria, royalties, research support, consultation fees or speaker’s fees from: Otsuka, Cambridge University Press, Advance Medical, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Axon Labs, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cantor Colburn, Covance, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, FlexPharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Impax, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, King, Luitpold, Novartis, Neurogen, Novadel Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Sunovion, Takeda, UCB (Schwarz) Pharma, Wyeth, Xenoport, Zeo.

Dr. Mai Uchida receives research support from the NIMH under Award Number 1K23MH122667-01.

Dr. T. Atilla Ceranoglu has received research support from PAMLab, Roche Inc., Pfizer, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Department of Defense, H. Lundbeck A/S, Magceutics, Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, and Massachusetts General Hospital. He has acted as a consultant for Guidepoint Global LLC and L.E.K. Consulting. Dr. Ceranoglu has received honoraria and travel support from Prima Barn och Vuxenpsykiatri.

Dr. Gagan Joshi is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number K23MH100450. In the last year he has received research support from the Demarest Lloyd, Jr. Foundation as a primary investigator (PI) for investigator-initiated studies. Additionally, he receives research support F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. as a site PI for multi-site trials. In the past three years, he has received research support from Pfizer and the Simons Center for the Social Brain. In addition, he has received honorarium from the Governor’s Council for Medical Research and Treatment of Autism in New Jersey and from NIMH for grant review activities. Finally, he received speaker’s honorariums from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, The Israeli Society of ADHD, the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the University of Jülich.

In the past year, Dr. Stephen V. Faraone received income, potential income, travel expenses continuing education support and/or research support from, Akili Interactive Labs, Arbor, Genomind, Ironshore, KemPharm/Corium, Ondosis, Otsuka, Rhodes, Shire/Takeda, Sunovion, Supernus, Tris, and Vallon. With his institution, he has US patent US20130217707 A1 for the use of sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitors in the treatment of ADHD. In previous years, he received support from: Alcobra, Aveksham, CogCubed, Eli Lilly, Enzymotec, Impact, Janssen, KemPharm, Lundbeck/Takeda, McNeil, Neurolifesciences, Neurovance, Novartis, Pfizer, and Vaya. He also receives royalties from books published by Guilford Press: Straight Talk about Your Child’s Mental Health; Oxford University Press: Schizophrenia: The Facts; and Elsevier: ADHD: Non-Pharmacologic Interventions. He is also Program Director of www.adhdinadults.com. Dr. Faraone is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 667302 and NIMH grants U01 MH109536-01, 1R01MH116037-01A1 and 1R01AG06495502.

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: AACAP, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Genentech, Headspace Inc., NIDA, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Roche TCRC Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Takeda/Shire Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tris, and NIH. Dr. Biederman and his program have received royalties from a copyrighted rating scale used for ADHD diagnoses, paid by Biomarin, Bracket Global, Cogstate, Ingenix, Medavent Prophase, Shire, Sunovion, and Theravance; these royalties were paid to the Department of Psychiatry at MGH. Through Partners Healthcare Innovation, Dr. Biederman has a partnership with MEMOTEXT to commercialize a digital health intervention to improve adherence in ADHD. Through MGH corporate licensing, Dr. Biederman has a US Patent (#14/027,676) for a non-stimulant treatment for ADHD, a US Patent (#10,245,271 B2) on a treatment of impaired cognitive flexibility, and a patent pending (#61/233,686) on a method to prevent stimulant abuse. In 2020: Dr. Biederman received an honorarium for a scientific presentation from Tris, and research support from the Food & Drug Administration. He receives honoraria from the Medlearning Inc and MGH Psychiatry Academy for tuition-funded CME courses. In 2019, Dr. Biederman was a consultant for Akili, Avekshan, Jazz Pharma, and Shire/Takeda. He received research support from Lundbeck AS and Neurocentria Inc. Through MGH CTNI, he participated in a scientific advisory board for Supernus. He received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for tuition-funded CME courses. In 2018, Dr. Biederman was a consultant for Akili and Shire. He received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for tuition-funded CME courses. In 2017, Dr. Biederman received research support from the Department of Defense and PamLab. He was a consultant for Aevi Genomics, Akili, Guidepoint, Ironshore, Medgenics, and Piper Jaffray. He was on the scientific advisory board for Alcobra and Shire. He received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for tuition-funded CME courses. In previous years, Dr. Biederman received research support, consultation fees, or speaker’s fees for/from the following additional sources: AACAP, Abbott, Akili, Alcobra, Alza, APSARD, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Avekshan, Boston University, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cambridge University Press, Celltech, Cephalon, The Children’s Hospital of Southwest Florida/Lee Memorial Health System, Cipher Pharmaceuticals Inc., Eli Lilly and Co., Esai, ElMindA, Forest Research Institute, Fundacion Areces (Spain), Forest, Fundación Dr.Manuel Camelo A.C., Glaxo, Gliatech, Hastings Center, Ironshore, Janssen, Juste Pharmaceutical Spain, Magceutics, McNeil, Medgenics, Medice Pharmaceuticals (Germany), Merck, MGH Psychiatry Academy, MMC Pediatric, NARSAD, NIDA, New River, NICHD, NIMH, Novartis, Noven, Neurosearch, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Pharmacia, Phase V Communications, Physicians Academy, The Prechter Foundation, Quantia Communications, Reed Exhibitions, Shionogi Pharma Inc, Shire, the Spanish Child Psychiatry Association, SPRITES, The Stanley Foundation, UCB Pharma Inc., Vaya Pharma/Enzymotec, Veritas, and Wyeth.

Ms. Maura DiSalvo, Ms. Abigail Farrell, Dr. Carrie Vaudreuil, and Ms. Emmaline Cook have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a generous philanthropic donation from Kent and Elizabeth Dauten (Chicago, Illinois). The authors acknowledge and thank Life Extension for the donation of inositol powder.

Contributor Information

Janet Wozniak, Janet Wozniak, MD, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA..

Abigail Farrell, Abigail Farrell, BS, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA..

Maura DiSalvo, Maura DiSalvo, MPH, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA..

Atilla Ceranoglu, Atilla Ceranoglu, MD, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA..

Mai Uchida, Mai Uchida, MD, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA..

Carrie Vaudreuil, Carrie Vaudreuil, MD, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA..

Gagan Joshi, Gagan Joshi, MD, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA..

Stephen V Faraone, Stephen V. Faraone, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, USA..

Emmaline Cook, Emmaline Cook, BA, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA..

Joseph Biederman, Joseph Biederman, MD, Clinical and Research Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacology and Adult ADHD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA..

References

- 1.Lewinsohn P, Klein D, Seeley J. Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: Prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. J Am Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 1995;34(4):454–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Meter A, Moreira ALR, Youngstrom E et al. Updated meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry . 2019;80(3):18r12180. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18r12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biederman J, Birmaher B, Carlson GA et al. National Institute of Mental Health Research Roundtable on Prepubertal Bipolar Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2001;40(8):871–878. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi G, Wilens T. Comorbidity in pediatric bipolar disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am . 2009;18(2):291–319. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K et al. Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 1995;34(7):867–876. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199507000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biederman J, Faraone S, Wozniak J, Mick E, Kwon A, Aleardi M. Further evidence of unique developmental phenotypic correlates of pediatric bipolar disorder: findings from a large sample of clinically referred preadolescent children assessed over the last 7 years. J Affect Disord . 2004;82(Suppl 1):S45–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickstein DP, Rich BA, Binstock AB et al. Comorbid anxiety in phenotypes of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol . 2005;15(4):534–548. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Findling RL, Stepanova E, Youngstrom EA et al. Progress in diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder among children and adolescents: an international perspective. Evid Based Ment Health . 2018;21:177–181. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu HY, Potter MP, Woodworth KY et al. Pharmacologic treatments for pediatric bipolar disorder: a review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2011;50(8):749–762. e739. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konstantakopoulos G, Dimitrakopoulos S, Michalopoulou PG. Drugs under early investigation for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs . 2015;24(4):477–490. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.1019061. doi: Epub 2015 Feb 23. PMID: 25704484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold L Eugene et al. Omega-3 fatty acid plasma levels before and after supplementation: correlations with mood and clinical outcomes in the omega-3 and therapy studies. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol . 2017;27(3):223–233. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0123. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloch MH, Qawasmi A. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2011;50(10):991–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel NC, DelBello MP, Cecil KM et al. Lithium treatment effects on Myo-inositol in adolescents with bipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry . 2006;60(9):998–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baraban JM, Worley PF, Snyder SH. Second messenger systems and psychoactive drug action: focus on the phosphoinositide system and lithium. Am J Psychiatry . 1989;146(10):1251–1260. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.10.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belmaker RH, Levine J. Natural Medications for Psychiatry: Considering the Alternatives . 2nd. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Inositol in the treatment of psychiatric disorders; p. 111. In: Mischoulon D, Rosenbaum JF, eds. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Case KC, Salsaa M, Yu W, Greenberg ML. Regulation of Inositol Biosynthesis: Balancing Health and Pathophysiology. Handb Exp Pharmacol . 2020;259:221–260. doi: 10.1007/164_2018_181. doi: PMID: 30591968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michell RH. Do inositol supplements enhance phosphatidylinositol supply and thus support endoplasmic reticulum function. Br J Nutr . 2018;120(3):301–316. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518000946. doi: Epub 2018 Jun 3. PMID: 29859544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei H, Landgraf D, Wang G, McCarthy MJ. Inositol polyphosphates contribute to cellular circadian rhythms: implications for understanding lithium’s molecular mechanism. Cell Signal . 2018;44:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.01.001. doi: Epub 2018 Jan 11. PMID: 29331582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peet M, Horrobin DF. A dose-ranging study of the effects of ethyl-eicosapentaenoate in patients with ongoing depression despite apparently adequate treatment with standard drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry . 2002;59(10):913–919. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemets B, Stahl Z, Belmaker RH. Addition of omega-3 fatty acid to maintenance medication treatment for recurrent unipolar depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry . 2002;159(3):477–479. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemets H, Nemets B, Apter A, Bracha Z, Belmaker RH. Omega-3 treatment of childhood depression: a controlled, double-blind pilot study. Am J Psychiatry . 2006;163(6):1098–1100. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold LE, Young AS, Belury MA, Cole RM, Gracious B, Seidenfeld AM, Wolfson H, Fristad MA. Omega-3 fatty acid plasma levels before and after supplementation: correlations with mood and clinical outcomes in the omega-3 and therapy studies. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol . 2017;27(3):223–233. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0123. doi: Epub 2017 Feb 3. PMID: 28157380; PMCID: PMC5397211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fristad MA, Young AS, Vesco AT et al. A randomized controlled trial of individual family psychoeducational psychotherapy and omega-3 fatty acids in youth with subsyndromal bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol . 2015;25(10):764–774. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.013. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wozniak J, Biederman J, Mick E et al. Omega-3 fatty acid monotherapy for pediatric bipolar disorder: a prospective open-label trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol . 2007;17(6–7):440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkai AI, Dunner DL, Gross HA, Mayo P, Fieve RR. Reduced myo-inositol levels in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with affective disorder. Biol Psychiatry . 1978;13(1):65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davanzo P, Thomas MA, Yue K et al. Decreased anterior cingulate myo-inositol/creatine spectroscopy resonance with lithium treatment in children with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology . 2001;24(4):359–369. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukai T, Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Iwata N. A meta-analysis of inositol for depression and anxiety disorders. Hum Psychopharmacol . 2014;29(1):55–63. doi: 10.1002/hup.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Chan J, Tarko L, Hernandez M, Davis J, Woodworth Y, Biederman J. Correction: a randomized clinical trial of high eicosapentaenoic acid omega-3 fatty acids and inositol as monotherapy and in combination in the treatment of pediatric bipolar spectrum disorders: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry . J Clin Psychiatry . 2016;2015;7776(9)(11):e1153. 1548–55. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16lcx11151. doi: Erratum for. PMID: 27780327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children: Epidemiologic Version . Fort Lauderdale, FL: Nova University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orvaschel H. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version . 5th. Ft. Lauderdale: Nova Southeastern University: Center for Psychological Studies; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry . 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gracious BL, Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Discriminative validity of a parent version of the Young Mania Rating Scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2002;41(11):1350–1359. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Youngstrom EA, Danielson CK, Findling RL, Gracious BL, Calabrese JR. Factor structure of the Young Mania Rating Scale for use with youths ages 5 to 17 years. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol . 2002;31(4):567–572. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinberg WA et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry . 1997;54(11):1031–1037. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230069010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry . 1976;33(6):766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos A, Reed R. The ADHD Rating Scale-IV Checklist, Norms and Clinical Interpretation . New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lachar D, Bailley SE, Rhoades HM et al. New subscales for an anchored version of the brief psychiatric rating scale: construction, reliability, and validity in acute psychiatric admissions. Psychol Assess . 2001;13:384–395. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institute of Mental Health. CGI (Clinical Global Impression) Scale – NIMH. Psychopharmacol Bull . 1985;21(8):839–844. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test . Second. Bloomington, MN: Pearson, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale . 4th. San Antonia, TX: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C . Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) New York, NY: The Research Foundation for Mental Hygene, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.College Station, TX: StatCorp LLC; 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16 [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences . Second. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liao Y, Xie B, Zhang H, He Q, Guo L, Subramanieapillai M, Fan B, Lu C, McIntyre RS. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: A meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry . Transl Psychiatry . 2019 2021 Aug 5 7;Sep 5 7;911(1)(1):190. 465. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0515-5. doi: Erratum in. PMID: 31383846; PMCID: PMC6683166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okereke OI, Vyas CM, Mischoulon D et al. Effect of long-term supplementation with marine omega-3 fatty acids vs placebo on risk of depression or clinically relevant depressive symptoms and on change in mood scores: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2021;326(23):2385–2394. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.21187. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chengappa KN, Levine J, Gershon S et al. Inositol as an add-on treatment for bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord . 2000;2(1):47–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.020107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nierenberg AA, Ostacher MJ, Calabrese JR et al. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a STEP-BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry . 2006;163(2):210–216. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evins EA, Demopulos C, Yovel I et al. Inositol augmentation of lithium or valproate for bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord . 2006;8(2):168–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rucklidge JJ, Gately D, Kaplan BJ. Database analysis of children and adolescents with Bipolar Disorder consuming a micronutrient formula. BMC Psychiatry . 2010;10:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wozniak J, Petty CR, Schreck M, Moses A, Faraone SV, Biederman J. High level of persistence of pediatric bipolar-I disorder from childhood onto adolescent years: a four year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res . 2011;45(10):1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei H, Landgraf D, Wang G, McCarthy MJ. Inositol polyphosphates contribute to cellular circadian rhythms: Implications for understanding lithium’s molecular mechanism. Cell Signal . 2018;44:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.01.001. doi: Epub 2018 Jan 11. PMID: 29331582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trkulja V, Barić H. Current research on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the treatment of major depressive disorder: an evidence-based review. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology . 2021;1305:375–427. doi: 10.1007/978-981-33-6044-0_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L, Liu H, Kuang L, Meng H, Zhou X. Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of depressive disorders in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health . 2019;13:36. doi: 10.1186/s13034-019-0296-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]