Abstract

Background:

Arsenic alters immunological parameters including antibody formation and antigen-driven T-cell proliferation.

Objective:

We evaluated the cross-sectional relationship between urinary arsenic and the seroprevalence of hepatitis B (HBV) infection in the United States using data from six pooled cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2003–2014, N = 12,447).

Methods:

Using serological data, participants were classified as susceptible, immune due to vaccination, or immune due to past natural infection. We used multinomial logistic regression to evaluate the association between urinary DMA and HBV classification. A sensitivity analysis using total urinary arsenic (TUA) was also conducted. Both DMA and TUA were adjusted for arsenobetaine using a residual regression method

Results:

A 1-unit increase in the natural logarithm (ln) of DMA was associated with 40% greater adjusted odds of having immunity due to natural infection compared to being susceptible (Odds Ratio [aOR]: 1.40, 95% Confidence Intervals [CI] 1.15, 1.69), 65% greater odds of having immunity due to a natural infection (aOR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.34, 2.04) and 18% greater odds of being susceptible (aOR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.33) compared to being immune due to vaccination after adjusting for creatinine, age, sex, race, income, country of birth, BMI, survey cycle, serum cotinine, recent seafood intake, and self-reported HBV immunization status.

Conclusion:

In the U.S. general public, higher urinary arsenic levels were associated with a greater odds of having a serological classification consistent with a past natural hepatitis B infection after adjusting for other risk factors. Additionally, higher urinary arsenic levels were linked to a greater odds of not receiving hepatitis B vaccinations. Given the cross-sectional nature of this analysis, more research is needed to test the hypothesis that environmentally relevant exposure to arsenic modulates host susceptibility to hepatitis B virus.

Keywords: Surface antibody, HBV, Core antibody, Viral hepatitis, Hepatitis surface antigen, Anti-HBs, Anti-HBc, Immunotoxicity, Infectious disease, Antibody responses, Heavy metals, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

Chronic arsenic exposure is immunotoxic (Burchiel et al., 2009; Dangleben et al., 2013; Martin-Chouly et al., 2011; Soto-Peña et al., 2006). Considering that approximately 100 million people worldwide are chronically exposed to arsenic through their drinking water (Naujokas et al., 2013), it is important to examine the potential for arsenic to influence human susceptibility to infectious agents. In vitro studies using cell culture have reported that high doses of arsenic increase apoptotic rates in B-cells, T-cells, macrophages and neutrophils (Dangleben et al., 2013). Additionally, a well-designed in vivo study using mice demonstrated that environmentally-relevant inorganic arsenic exposure levels of 100 parts per billion of arsenite in drinking water enhanced the morbidity and mortality of H1N1 influenza (Kozul et al., 2009). Epidemiological studies also report that chronic arsenic exposure is associated with higher rates of infectious diseases including pneumonia, respiratory illnesses, and diarrheal disease (Argos et al., 2010; Parvez et al., 2010; Rahman et al., 2011; Raqib et al., 2009., George et al., 2015).

There is also growing evidence gathered from epidemiological studies that demonstrate that arsenic exposure is associated with antibodies against viral hepatitis. Viral hepatitis is a common infectious disease that inflames the liver, which is also a target organ for arsenic toxicity. There are at least five different types of viral hepatitis: A, B, C, D and E. Data from a large prospective birth cohort in Bangladesh showed that women with higher arsenic exposure had higher odds of hepatitis E virus seroconversion during pregnancy (Heaney et al., 2015). In the United States, a large cross-sectional study showed that arsenic exposure was associated with higher hepatitis A seroprevalence although we were unable to determine if arsenic exposure increased susceptibility to the virus (Cardenas et al., 2016). The hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is also a common hepatitis virus that is mainly transmitted through contact with infected blood, semen, or other bodily fluid (CDC, 2010a). A vaccine to prevent HBV infection was first developed in the 1980s and recommended for high risk populations including health care workers, sexually active individuals, men who have sex with men, individuals travelling to countries where hepatitis is common, and intravenous drug users (Mast et al., 2006; Weinbaum et al., 2008). As of 1991 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends all newborns receive HBV vaccination with the final dose administered at 18 months of age. This prevention strategy has been highly effective and the incidence of hepatitis B has decreased dramatically (Smith et al., 2012). As of 2014, the CDC recorded 2953 new cases of acute hepatitis B in the United States although the actual number of new cases is estimated to be 6.48-times higher (CDC, 2010b).

While preventing contact with infected biological materials and vaccination are the most effective ways to reduce HBV transmission, identifying environmental factors that can affect HBV infection could inform novel prevention strategies, particularly in developing countries facing ubiquitous exposure to environmental toxicants and high prevalence rates for infectious diseases. Thus, the objective of this study was to investigate the association between arsenic exposure and HBV status as defined by serological markers in a large representative sample of the U.S. population. We hypothesized that higher urinary arsenic concentration would be associated with a higher prevalence of a natural HBV infection after controlling for other risk factors as potential confounders. We further hypothesized that only individuals with no doses of the hepatitis B vaccine would be at increased odds of infection with elevated arsenic exposure.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

We used data from six consecutive cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) which is representative of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population at midpoint between the 2003–2014. These cycles were selected because urinary arsenic measurements and serological markers for HBV were available in participants aged 6 years and older and collected consistently across all 6 cycles. Informed consent was obtained from all survey participants and study protocols were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board (CDC, 2012).

NHANES only performs urinary arsenic measurements in one third of participants aged 6 years and older (n = 15,663 in the six survey cycles). Of those participants, 14,285 also had complete data available on their HBV serology for classification and 12,492 with complete covariate information. To avoid potential confounding by immunodeficiency, we excluded participants with a positive or equivocal HIV test (n = 26), unclear classification of hepatitis B serology (n = 128) or with acute or chronic Hepatitis B infection (n = 33) leaving a total of N = 12,447 participants for this analysis.

2.2. Serological markers

At the time of examination, participants provided blood via venipuncture. Samples were processed by the Division of Viral Hepatitis. Hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) was qualitatively measured using a solid-phase competitive enzyme immunoassay (Ausab, Abbott Laboratories). A quantitative enzyme-linked immunoassay was used to measure the HBV core antibody, anti-HBc (Vitros, anti-HBc ELISA). If the sample tested positive for anti-HBc it was also tested for the hepatitis B surface antigen, HBsAg (Auszyme, Abbott Laboratories). If the sample tested negative for anti-HBc it was coded as negative for HBsAg. All serological markers are qualitatively reported as positive or negative by NHANES (CDC, 2014a, 2014b).

We used the clinical combination of HBV antibodies and the hepatitis B antigen (HBsAg) to determine three categorical classification for hepatitis B infection. If participants were coded negative for anti-HBs, anti-HBc and HBsAg they are considered susceptible to HBV (i.e. never infected or vaccinated). If participants were coded positive for both anti-HBs and anti-HBc but not HBsAg they were considered as having a past natural infection. Finally, if participants were coded positive for anti-HBs but negative for anti-HBc and HBsAg, they are considered to be immune due to vaccination (CDC, 2010b; Mast et al., 2005). Interpretation of the serological markers provided by the CDC are summarized in Table 1. We were unable to distinguish between acute or chronic HBV infection because the immunoglobulin M class of anti-HBc which becomes detectable at the onset of acute hepatitis B was not measured in NHANES. Therefore, we excluded 33 participants from this category and 128 with an unclear combination of hepatitis B serological markers that had complete exposure and covariate information.

Table 1.

Classification of hepatitis B viral status based on serological markers available in NHANES 2003–2014.

| Serological marker | Abbreviation | Susceptible | Vaccinated | Natural Infection | Acute/Chronic HBV infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hep B Surface Antibody | Anti-HBs | - | + | + | - |

| Hep B Surface Antigen | HBsAg | - | - | - | + |

| Total Hep B Core Antibody | Anti-HBc | − | − | + | + |

| Sample size | 8520 | 3491 | 436 | 33a | |

| Weighted prevalence (95% CI) | 71.9% (70.8 0–72.9) | 25.0% (23.9–26.0) | 3.1% (2.7–3.5) | − |

These individuals were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient power across covariates.

2.3. Urinary arsenic assessment

Urine samples were analyzed within 3 weeks of collection using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to inductively coupled-plasma dynamic reaction cell-mass spectrometry (ICP-DRC-MS). This method quantifies total urinary arsenic and species from which we selected dimethylarsenic acid (DMA), arsenobetaine (AsB), and total urinary arsenic for analyses (Caldwell et al., 2008). The corresponding limits of detection (LODs) for total urinary arsenic were 0.6 μg/L (2003–2004), 0.74 μg/L (2005–2010), 1.25 μg/L (2011–2012) and 0.26 μg/L (2013–2014). The LOD for DMA and AsB were 1.7 μg/L and 0.4 μg/L, respectively for the 2003–2010 NHANES cycles. For the 2011–2012 NHANES cycle the LOD for DMA and AsB was 1.8 μg/L and 0.28 μg/ respectively. Finally, for the 2013–2014 NHANES cycle the LOD for DMA and AsB was 1.91 μg/L and 1.16 μg/L. The proportion of urine samples that were below the limit of detection (LOD) in our study for all the cycles was 1.31% for total urinary arsenic, 17.32% for DMA and 43.54% for AsB. Concentrations below the LOD are reported in NHANES as the LOD divided by the square root of two for each analyte.

AsB is found in seafood and considered to be relatively nontoxic (Choi et al., 2010; Heinrich-Ramm et al., 2002). Therefore, we uses a residual method to provide an estimate of arsenic exposure that minimizes the potential influence of seafood arsenic intake (Jones et al., 2016). This approach yields a calibrated urinary biomarker by regressing DMA by AsB and extracting the model residuals [e.g. ln(DMAi)= β0 + β1 ×ln(arsenobetainei) + εi]. Additionally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that used a residual adjusted total urinary arsenic [e.g. ln(Total As) = β0 + β1 ×ln(arsenobetainei) + εi]. Finally, we used data from 24-h dietary recall to create a variable of recent seafood consumption (yes/no) (Welch et al., 2018). Urinary creatinine was measured by an enzymatic method by a Roche/Hitachi Modular P Chemistry Analyzer. Urinary creatinine was used as a separate independent variable to adjust for differences in urine dilution (Barr et al., 2005).

2.4. Covariates

Variables that were considered a priori as potential confounders for the association between urinary arsenic and hepatitis B serological classification included sex, age, race, country of birth, self-reported hepatitis B vaccination, body mass index (BMI), family-income-to poverty ratio, urinary creatinine levels, serum cotinine levels, recent seafood intake and survey cycle. For example, it has been shown that HBV serology in the U.S. is associated with sex, age, race and country of birth (Wasley et al., 2010). In addition, age, sex, race, BMI, urinary creatinine, smoking and survey cycle have been shown to be associated with urinary arsenic concentrations (Barr et al., 2005; Welch et al., 2018). We adjusted for self-reported hepatitis B vaccination as a predictor of hepatitis B serology and family-income to poverty ratio to control for socioeconomic status.

Race/ethnicity was self-reported as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other Hispanics, and other race including multiracial. Individuals reporting to be multiracial, non-Hispanic Asian or of another race were collapsed by NHANES into the single “other race – including multi-racial” category. BMI was calculated by dividing measured weight in kilograms by measured height in meters squared. BMI was classified as underweight (< 18.5), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), and obese (≥ 30). For participants < 20 years of age, BMI classification was defined using the CDC growth charts for age- and sex-specific cutoffs to describe the study sample. However, we used BMI as a continuous measure for adjustment in statistical models.

2.5. Statistical analysis

We combined six consecutive NHANES survey cycles from 2003 to 2014. To account for the complex survey design, subpopulation weights from subsample A of NHANES were used to construct the combine sampling weights for the pooled analysis by multiplying the subsample weights by 1/6, as recommended by NHANES.

Urinary arsenic concentrations (DMA, AsB, and TUA) were right skewed and subsequently natural log-transformed. The available sample size and weighted proportion along with missing data were calculated for all covariates considered. In bivariate analyses, continuous covariates were categorized to examine and describe the distribution of the serological classification of hepatitis B by population characteristics. The weighted seroprevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of hepatitis B classification were estimated across categorical levels of all covariates, including quartiles of TUA (not adjusted for residuals). Lastly, weighted multinomial logistic regression models were used to evaluate the adjusted association between the calibrated urinary arsenic biomarkers (DMA_residual and TUA_residual) and the three mutually exclusive serological classification of hepatitis B defined as: past natural infection, HBV vaccination, and susceptible to HBV infection. These models were adjusted for natural log-transformed creatinine (continuous), age (continuous), gender (categorical), BMI (continuous), family income to poverty ratio (continuous), foreign born (categorical), race (categorical) survey cycle (categorical), log-transformed serum cotinine (continuous), 24-h seafood consumption (yes/no) and self-reported hepatitis B immunization (categorical). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were estimated for the three potential comparisons of interests among hepatitis B classification: i) a past natural infection vs. being susceptible to HBV infection, ii) past natural infection vs. HBV vaccine induced immunity, and c) susceptible to infection vs HBV vaccine induced immunity. We report P values for tests performed and 95% CIs to evaluate effect sizes and significance of associations. Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata using the survey command to account for the complex designs implemented in NHANES (version 12.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

3. Results

The weighted percentiles of each serological classification indicative of past natural HBV infection, HBV vaccination, and no HBV antibodies is shown in Table 1. Across all six NHANES survey cycles (2002–2014), the weighted seroprevalence of individuals who had serology indicative of a past natural HBV infection was 3.1% (95% CI: 2.7%, 3.5). The weighted prevalence of individuals who had serology indicative of HBV vaccination was 25.0% (95% CI: 23.9, 26.0). Finally, the weighted prevalence of individual who had serology indicative of being susceptible to HBV was 71.9% (95% CI: 70.8, 72.9). The unadjusted geometric mean of DMA was not different between people who reported having received all three-doses of HBV vaccine (3.65 μg/L, 95% CI: 3.52, 3.79) and those who reported never receiving any HBV vaccine doses (3.54 μg/L, 95% CI: 3.41, 3.66).

The bivariate relationship between HBV serological classification, selected demographic characteristics, and urinary arsenic concentrations are presented in Table 2. The weighted prevalence of individuals with a history of natural infection was highest among individuals in the highest quartile of DMA compared to the lowest ( = 5.1%, 95% CI: 4.1–6.1% vs = 2.5%, 95% CI: 1.7–3.3%). Whereas, the weighted prevalence of individuals who had no HBV antibodies present and therefore classified as susceptible to HBV infection was lowest among individuals with the highest quartile of DMA compared to the lowest ( = 68.8%, 95% CI: 66.3–71.2% vs = 73.1%, 95% CI: 71.1–75.2%). Yet, the weighted prevalence of individuals with a history of immunization did not differ between quartiles of DMA ( = 26.1%, 95% CI: 23.9–28.3% vs = 24.4%, 95% CI: 22.3–26.4%).

Table 2.

Weighted serological prevalence of Hepatitis B classification based on serological evidence among socio-demographic and total urinary arsenic categories in the combined survey cycles (2003–2014).

| Population Characteristic | N | Susceptible | History of vaccination | History of natural infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 6193 | 73.8% (72.4, 752.) | 22.8% (21.4, 24.1) | 3.4% (2.8, 4.1) |

| Female | 6254 | 70.0% (68.5, 71.6) | 27.2% (25.7, 28.7) | 2.8% (2.3, 3.3) |

| Age | ||||

| 6–18 | 3734 | 51.4% (48.8, 53.9) | 48.3% (45.7, 51.0) | 0.3% (0.1, 0.5) |

| 19–40 | 3486 | 64.7% (62.2, 67.2) | 33.3% (30.8, 35.7) | 2.0% (1.4, 2.5) |

| 41–85 | 5227 | 84.4% (83.2, 85.7) | 10.6% (9.5, 11.7) | 4.9% (4.1, 5.7) |

| Race | ||||

| Mexican American | 2482 | 72.9% (71.3, 74.6) | 26.1% (24.4, 27.7) | 1.0% (0.6, 1.4) |

| Other Hispanic | 945 | 68.0% (64.6, 71.5) | 27.3% (23.9, 30.7) | 4.6% (2.7, 6.5) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 5237 | 74.4% (72.9, 75.8) | 23.7% (22.3, 25.1) | 1.9% (1.5, 2.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2853 | 65.2% (62.8, 67.6) | 28.1% (26.1, 30.1) | 6.7% (5.5, 7.9) |

| Other Race – including multi-racial | 930 | 57.4% (52.9, 61.9) | 31.0% (27.5, 34.4) | 11.6% (8.3, 14.9) |

| Country of Birth | ||||

| Born in the US | 10,038 | 72.4% (71.3, 73.6) | 25.4% (24.3, 26.5) | 2.1% (1.8, 2.6) |

| Born Elsewhere | 2409 | 68.4% (65.9, 70.9) | 22.6% (20.2, 25.1) | 8.9% (7.3, 10.5) |

| Missing | 6 | |||

| Self-reported Hep. B Vaccination | ||||

| Yes, all three Doses | 5479 | 49.3% (47.3, 51.1) | 48.9% (47.1, 50.8) | 1.8% (1.4, 2.2) |

| Less than three doses | 291 | 62.5% (54.7, 70.3) | 34.1% (26.5, 41.7) | 3.4% (0.5, 6.2) |

| No Doses | 5456 | 89.3% (88.2, 90.3) | 6.6% (5.7, 7.4) | 4.2% (3.5, 4.9) |

| Don't Know | 1221 | 76.1% (72.8, 79.4) | 21.1% (17.9, 24.25) | 2.8% (1.7, 3.9) |

| Missing | 11 | |||

| Body mass index classification | ||||

| Underweight | 282 | 60.9% (53.3, 68.6) | 35.4% (27.6, 44.6) | 3.7% (0.5, 6.8) |

| Normal weight | 4794 | 62.5% (60.3, 64.6) | 34.4% (32.0, 36.4) | 3.1% (2.4, 3.8) |

| Overweight | 3508 | 76.2% (74.6, 77.7) | 20.4% (17.8, 21.1) | 3.4% (2.6, 4.1) |

| Obese | 3863 | 79.3% (77.7, 80.9) | 17.9% (16.5, 19.4) | 2.7% (2.0, 3.4) |

| Missing | 111 | |||

| Survey Year | ||||

| 2003–2004 | 2123 | 72.6% (69.3, 75.9) | 23.5% (20.6, 26.4) | 3.9% (2.9, 4.9) |

| 2005–2006 | 2145 | 71.2% (69.4, 72.9) | 25.3% (23.7, 26.8) | 3.5% (2.4, 4.6) |

| 2007–2008 | 2018 | 73.7% (71.7, 75.7) | 23.5% (21.3, 25.6) | 2.8% (1.9, 3.7) |

| 2009–2010 | 2290 | 71.6% (68.5, 74.7) | 24.9% (22.1, 27.7) | 3.5% (2.3, 4.6) |

| 2011–2012 | 1867 | 71.1% (68.0, 74.1) | 26.2% (23.1, 29.3) | 2.7% (1.7, 3.8) |

| 2013–2014 | 2004 | 72.2% (69.7, 74.6) | 25.3% (23.2, 27.4) | 2.5% (1.6, 3.4) |

| Family-income to poverty ratio (weighted tertiles) | ||||

| Low (0–1.77) | 5800 | 69.7% (67.8, 71.7) | 26.5% (24.6, 28.3) | 3.7% (3.1, 4.5) |

| Medium (> 1.78–3.97) | 3787 | 74.5% (72.7, 76.3) | 22.3% (20.7, 23.9) | 3.1% (2.4, 3.9) |

| High (> 3.98–5) | 2860 | 71.3% (69.3, 73.3) | 26.4% (24.4, 28.3) | 2.4% (1.6, 3.1) |

| Missing | 872 | |||

| Creatinine (weighted tertiles) mg/dL | ||||

| Low (5–73) | 3771 | 73.1% (71.1, 75.2) | 23.3% (21.3, 25.3) | 3.6% (2.6, 4.4) |

| Medium (74–143) | 4321 | 71.8% (70.2, 73.4) | 25.1% (23.6, 26.5) | 3.1% (2.4, 3.8) |

| High (144–800) | 4355 | 70.7% (68.9, 72.5) | 26.7% (25.0, 28.3) | 2.6% (2.1, 3.3) |

| Missing | 2 | |||

| Serum Cotinine (weighted tertiles) ng/mL | ||||

| 0.011–0.021 | 4051 | 72.4% (70.5, 74.4) | 25.1% (23.2, 26.9) | 2.5% (1.8, 3.1) |

| 0.022–0.301 | 4416 | 71.5% (69.8, 73.3) | 24.9% (23.2, 26.6) | 3.6% (2.8, 4.3) |

| 0.302–1820 | 3980 | 71.6% (69.6, 73.6) | 25.1% (23.4, 26.8) | 3.3% (2.6, 4.0) |

| Missing | 46 | |||

| 24-h seafood consumption | ||||

| Yes | 1826 | 68.7% (65.1, 72.3) | 24.6% (21.5, 27.7) | 6.7% (5.0, 8.4) |

| No | 10,621 | 72.4% (71.4, 73.5) | 25.1% (24.0, 26.1) | 2.5% (2.0, 2.9) |

| Missing | 636 | |||

| Total Urinary Arsenic(weighted Quartiles) (μg/L) | ||||

| 0.35–3.7 | 2862 | 73.7% (71.6, 75.8) | 24.1% (22.0, 26.2) | 2.2% (1.5, 2.9) |

| > 3.7–7.2 | 3162 | 71.9% (69.9, 73.4) | 25.8% (23.9, 27.7) | 2.4% (1.6, 3.1) |

| > 7.2–15.07 | 3289 | 71.5% (69.5, 73.1) | 25.6% (23.6, 27.5) | 2.9% (2.1, 3.8) |

| > 15.07–1470 | 3134 | 70.4% (67.8, 73.1) | 24.6% (22.3, 26.9) | 4.9% (4.0, 5.9) |

| Urinary DMA Quartiles (weighted Quartiles) (μg/L) | ||||

| 0.001–2.0 | 2892 | 73.1% (71.1, 75.2) | 24.4% (22.3, 26.4) | 2.5% (1.7, 3.3) |

| > 2.0–3.51 | 3040 | 73.0% (71.2, 74.8) | 25.1% (23.3, 26.9) | 1.9% (1.2, 2.6) |

| > 3.51–5.9 | 3181 | 72.5% (70.5, 74.5) | 24.5% (22.6, 26.4) | 2.9% (2.2, 3.7) |

| > 5.9–270 | 3334 | 68.8% (66.3, 71.2) | 26.1% (23.9, 28.3) | 5.1% (4.1, 6.1) |

We used multinomial logistic regression models to evaluate the association between DMA_residual and the three HBV serological classifications (Table 3). Adjusted associations were observed for log-transformed DMA_residual and TUA_residual with the serological categories for HBV. Specifically, for every unit increase in DMA_residual, the odds of having a past natural infection were 40% higher (aOR=1.40, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.69) compared to being susceptible to HBV infection. In addition, we also observed that for every unit increase in DMA_residual, the odds of having a past natural infection were higher by 65% (OR=1.65, 95% CI: 1.34, 2.04) compared to being immune due to HBV vaccination. In addition the odds of being susceptible were 18% higher (OR=1.18, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.33). These associations were robust to adjustment for multiple potential confounders. When modeling log-transformed TUA_residual in fully adjusted models our results were consistent but the magnitude of association was slightly attenuated. Namely, the odds of having a past natural infection were 23% higher (aOR = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.95, 1.59) for every 1-unit increase in TUA_residual compared to being susceptible to HBV infection. And, the odds of having a past natural infection were 34% higher (aOR=1.34, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.75) compared to vaccine-induced immunity. The proportion of people who were considered to be susceptible to infection versus having vaccine induced immunity was not associated with calibrated TUA concentration.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) for calibrated urinary arsenic concentrations (DMA residual and TUA residual) from a multinomial logistic regression models for three mutually exclusive serological classifications of hepatitis B as outcomes: susceptible, past natural hepatitis B infection, and vaccine-induced immunity to hepatitis B virus.

| Natural infection vs. Susceptible |

Natural infection vs. Vaccine-Induced Immunity |

Susceptible vs. Vaccine-Induced Immunity |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Odds Ratio (95% CIs) |

Odds Ratio (95% CIs) |

Odds Ratio (95% CIs) |

| DMA_residual | 1.40 (1.15, 1.69) | 1.65 (1.34, 2.04) | 1.18 (1.05, 1.33) |

| P = 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.005 | |

| TUA_residual | 1.23 (0.95, 1.59) | 1.34 (1.02, 1.75) | 1.08 (0.97, 1.21) |

| P = 0.10 | P = 0.034 | P = 0.14 |

DMA residuals are the regression residuals from ln(DMAi)= β0 + β1 ×ln(arsenobetainei) + εi.

TUA residual are the regression residuals from ln(Total As)= β0 + β1 ×ln(arsenobetainei) + εi.

Odds ratios estimates from a multinomial logistic regression model adjusted for log-transformed creatinine (continuous), age (continuous), sex (categorical), race (categorical), family poverty-income ratio (continuous), country of birth (categorical), BMI (continuous), survey year (categorical), log-transformed serum cotinine (continuous), recent seafood consumption (yes/no) and self-reported Hepatitis B immunization (categorical).

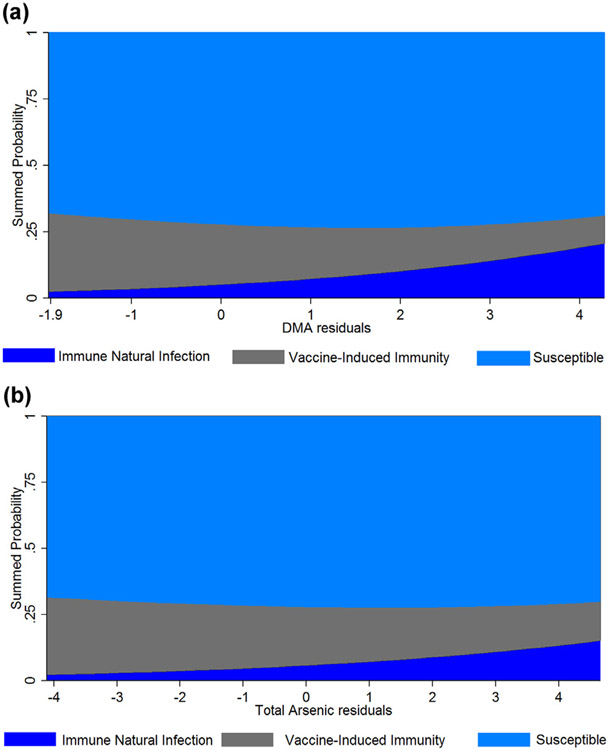

Together these results suggest that urinary arsenic concentration is associated with higher odds of having a past natural hepatitis B infection. Adjusted predicted probabilities from the multinomial logistic regression model for calibrated DMA and TUA are shown in Fig. 1 over the range of urinary arsenic concentration. Associations were robust and consistent but slightly attenuated in magnitude when urinary arsenic concentration was modeled as TUA.

Fig. 1.

Predicted cross-sectional probabilities for the classification of Hepatitis B serology across the range of A) calibrated urinary DMA concentration and B) calibrated total urinary Arsenic concentration. Predicted probabilities estimated from the adjusted multinomial regression model using mean levels of ln-transformed creatinine, log-transformed serum cotinine, age, family-income to poverty ratio, BMI, race (white), sex (male), survey year (2007–2008), country of birth (US), self-reported Hepatitis B vaccination (all three-doses) and seafood consumption (no).

We further examined the association between urinary arsenic concentration and hepatitis B serological classification by stratifying on self-reported hepatitis B immunization status (Table 4). Overall, the positive associations between DMA_residual and HBV natural infection compared to having vaccine induced immunity or being susceptible remained fairly consistent regardless of self-reported vaccination status. Although due to very small sample size (n = 291) we could not obtain reliable estimates for the less than three vaccine dose category. Importantly, the association between DMA_residual and natural HBV infection compared to having vaccine induced immunity was strongest among the strata of individuals who received the full course of HBV vaccination. When we modeled the exposure as TUA_residual the results were similar but the strength and magnitude of the association were more modest (Supplementary Table 1). As sensitivity analyses we restrict to individuals with non-detectable urinary arsenobetaine concentration. Associations were consistent in direction and magnitude but estimates crossed the null. However, in this restricted analysis the number of individuals with a serology consistent with a past natural Hepatis B infection was only 121 limiting the power of our analyses (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 4.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) for calibrated DMA urinary arsenic concentration stratified by self-reported immunization history from multinomial logistic regression models for three mutually exclusive serological classifications of hepatitis B as outcomes: susceptible, past natural hepatitis B infection, and vaccine-induced immunity to hepatitis B virus.

| Comparisons | Three-doses | Less than 3 doses* |

No Doses | Don’t Know |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Infection vs.Susceptible | 1.35 (0.95, 1.92) | 2.47 (0.39, 15.7) | 1.44 (1.13, 1.83) | 1.16 (0.64, 2.09) |

| P = 0.10 | P = 0.33 | P = 0.003 | P = 0.62 | |

| Natural Infection vs. Vacc. induced immunity | 1.67 (1.17, 2.38) | 5.75 (0.87, 38.1) | 1.38 (0.96, 1.98) | 1.25 (0.64, 2.46) |

| P = 0.005 | P = 0.10 | P = 0.08 | P = 0.51 | |

| Susceptible vs. Vaccine induced immunity | 1.24 (1.08, 1.42) | 2.33 (1.33, 4.07) | 0.96 (0.73, 1.26) | 1.08 (0.73, 0.60) |

| P = 0.002 | P= 0.003 | P = 0.76 | P = 0.70 |

Odds ratios estimates from a multinomial logistic regression model adjusted for log-transformed creatinine (continuous), age (continuous), sex (categorical), race (categorical), family poverty-income ratio (continuous), country of birth (categorical), BMI (continuous), survey year (categorical), log-transformed serum cotinine (continuous) and recent seafood consumption (yes/no).

Model estimates not using NHANES sampling design due to non-convergence because of small sample size strata (n = 291).

4. Discussion

We observed a positive exposure-response relationship between urinary arsenic concentration and higher odds of having hepatitis B serology reflecting a past HBV infection in the general U.S. population. This conclusion is based on the premise that total anti-HBc is only detected following natural HBV infection and not after vaccination (Wasley et al., 2010). However, the cross-sectional study design and reliance on self-reported medical history makes it difficult to ascertain the exact nature of the observed exposure-response relationships. For instance, it is also possible that arsenic modulated the host response to HBV vaccine or people who were at greater risk of HBV infection resided in geographic regions with higher arsenic exposure resulting in geographical confounding. However, individuals that respond to the hepatitis B vaccine with no previous history of HBV infections are typically only positive for anti-HBs (Goldstein et al., 2005). We observed a positive association between urinary arsenic concentrations among individuals only positive for anti-HBs (immune due to vaccination), or both anti-HBs and anti-HBc which indicates a past natural HBV infection (Mast et al., 2005). We also observed a similar positive association between urinary arsenic concentration and having a natural infection among people who reported being vaccinated (all three doses) and those that self-reported receiving no doses of the vaccine. This raises the possibility that arsenic exposure may modulate the host cellular immune response to HBV vaccine and warrants further study.

The vaccine-induced protection produced by HBV immunization is hypothesized to occur through the immune-memory induced by the selective expansion and differentiation of clones of antigen specific B and T lymphocytes (Banatvala and Damme, 2003). Both the innate and the adaptive immune system act synergistically to activate and execute the immune response following immunizations. However, it is the adaptive immune system that allows the host to produce both the antigen-specific response and the creation of an immune memory. There is evidence that arsenic affects this adaptive immune system. Experimental studies in zebra-fish demonstrated that arsenic concentrations at environmentally-relevant doses compromise the overall innate and adaptive immune system (Mattingly et al., 2009; Nayak et al., 2007). In vivo studies show that arsenic increases the percentage and total levels of CD8 + T-cells and decreases cytokine production (Kozul et al., 2009). This type of lymphocyte response is thought to contribute to the development, progression, and down regulation of the pathogenic immune response (Pennock et al., 2013). Alterations in the expression of genes related to the immune response, including genes involved in T-cell receptor signaling have also been observed with increased exposure to inorganic arsenic (Andrew et al., 2008; Biswas et al., 2008). T-cells are an important part of the immune system that play a key role in the immune response to infections and vaccine induce immunity (Belkaid and Rouse, 2005). Recent evidence from two different cohort studies have demonstrated that in utero exposure to arsenic altered the CD4 + / CD8 + T cell ratios (Koestler et al., 2013) and also slightly decreased the proportion of B-cells in newborns (Kile et al., 2014). The key role of T-cells in stimulating B-cells for the production of antibodies makes T-cell production and regulation a likely target for the effect of arsenic in altered immune response to the hepatitis A that we have previously reported (Cardenas et al., 2016), and hepatitis B virus reported here. In addition, we have also reported associations between urinary arsenic concentration and varicella zoster virus IgG antibodies in the general US population (Cardenas et al., 2015).

The results of our analysis support the hypothesis that people exposed to higher levels of arsenic had a greater risk of a natural infection even when the serology and self-reported vaccination status indicated that they were immune to HBV. Additional prospective epidemiological studies would be needed to confirm this hypothesis. Furthermore, there is still much to learn about how arsenic may affect host susceptibility to HBV or modulate the effectiveness of vaccine response. However, it is worth noting that our analysis has several strengths. Namely, NHANES collects information from a large representative sample of the US population. We combined five survey cycles spanning 10 years of data. This increased our sample size, as well as, expanded the time window captures in this cross-sectional analysis. Urinary arsenic measurements were rigorous and represented a range of exposures commonly encountered by the U.S. population. However, this is a cross sectional analysis and relied on spot urinary samples which may not capture individual fluctuations in arsenic exposure or previous arsenic exposure history. Furthermore, urinary arsenic concentrations reflect all routes of exposure. We did examine urinary arsenic concentrations using two metrics (DMA and TUA) and both yielded similar results. However, these urinary arsenic metabolites can be influenced by organoarsenicals in seafood (Molin et al., 2015; Navas-Acien et al., 2011). We attempted to minimize the influence of these less toxic organoarsenicals by using a residual method that adjusted for arsenobetaine (Jones et al., 2016) and self-reported seafood intake in the past 24-h. This approach provides a better estimate of inorganic arsenic exposure, however it does not necessarily identify the source of arsenic exposure which could be coming from water, dust, air, or rice (Gilbert-Diamond et al., 2011; Nigra et al.,2017). Additionally, the risk of natural HBV infection can be higher among certain racial groups such as Asians which are captured in the “other race” category in NHANES can also have higher urinary arsenic concentration (Awata et al., 2017). Though we excluded individuals with HIV participants with other infections like influenza or tuberculosis could have been included in the analyses. While we did adjust for race/ethnicity and country of origin, there is a potential for residual confounding due to the cross-sectional nature of this data. Additionally, medical histories including self-reported vaccination status and disease history might have substantial misclassification due to recall and reporting bias. While we did adjust our analysis for important risk factors for HBV infection and urinary arsenic concentration as potential confounders, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding or reverse causality because viral hepatitis inflames the liver which could modify arsenic metabolism and subsequent excretion arsenic in the urine. However, our hypothesis was based on strong experimental and epidemiological data indicating the causal role of arsenic in modulating the immune response.

5. Conclusions

Our study supports the hypothesis that arsenic exposure at environmentally-relevant levels is associated with a higher odds of HBV infection in the general U.S. population. While the cross-sectional nature of NHANES makes it difficult to ascertain the exact nature of the exposure-response relationship or infer causal relationships, these results raise the intriguing possibility that higher arsenic exposure, a ubiquitous environmental contaminant, may influence susceptibility to HBV infection. Given the public health impact of HBV and prevalence of arsenic exposure in the United States and other countries, further studies are warranted that examine the potential for arsenic exposure to alter host susceptibility to HBV infection or modulate the efficacy of HBV vaccine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01 ES023441).

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

All authors declared that no competing interests exist.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.023.

References

- Andrew AS, Jewell DA, Mason RA, Whitfield ML, Moore JH, Karagas MR, 2008. Drinking-water arsenic exposure modulates gene expression in human lymphocytes from a US population. Environ. Health Persp 116 (4), 524–531. 10.1289/ehp.10861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argos M, Kalra T, Rathouz PJ, Chen Y, Pierce B, Parvez F, et al. , 2010. Arsenic exposure from drinking water, and all-cause and chronic-disease mortalities in Bangladesh (HEALS): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 376 (9737), 252–258. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60481-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awata H, Linder S, Mitchell LE, Delclos GL, 2017. Biomarker levels of toxic metals among Asian Populations in the United States: nhanes 2011–2012. Environ. Health Persp 125, 306–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banatvala J, Damme P, 2003. Hepatitis B vaccine–do we need boosters? J. Viral Hepat (1), 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Wilder LC, Caudill SP, Gonzalez AJ, Needham LL, Pirkle JL, 2005. Urinary creatinine concentrations in the US population: implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ. Health Perspect 113 (2), 192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch B, Smit E, Cardenas A, Hystad P, Kile ML, 2018. Trends in urinary arsenic among the US population by drinking water source: results from the National Health and Nutritional Examinations Survey 2003–2014. Environ. Res 162, 8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y, Rouse BT, 2005. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat. Immunol 6 (4), 353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas R, Ghosh P, Banerjee N, Das J, Sau T, Banerjee A, et al. , 2008. Analysis of T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion in the individuals exposed to arsenic. Hum. Exp. Toxicol (5), 381–386. 10.1177/0960327108094607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchiel SW, Mitchell LA, Lauer FT, Sun X, McDonald JD, Hudson LG, et al. ,2009. Immunotoxicity and biodistribution analysis of arsenic trioxide in c57bl/6 mice following a 2-week inhalation exposure. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 241 (3), 253–259. 10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell KL, Jones RL, Verdon CP, Jarrett JM, Caudill SP, Osterloh JD, 2008. Levels of urinary total and speciated arsenic in the U.S. population: national health and nutrition examination survey 2003–2004. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol 19 (1), 59–68. 10.1038/jes.2008.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A, Smit E, Houseman EA, Kerkvleit NI, Bethel JW, Kile ML, 2015. Arsenic exposure and prevalence of the varicella zoster virus in the United States: nhanes (2003–2004 and 2009–2010). Environ. Health Perspect 123 (6), 590–596. 10.1289/ehp.1408731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A, Smit E, Bethel JW, Houseman EA, Kile ML, 2016. Arsenic exposure and seroprevalence of total hepatitis A antibodies in the US population: nhanes, 2003–2012. Epidemiol. Infect 144 (8), 1641–1651. 10.1017/S0950268815003088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2010a. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Viral hepatitis surveillance–United States, 2010. Available: 〈http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics/2010Surveillance/PDFs/2010HepSurveillanceRpt.pdf〉. (accessed October 16, 2013).

- CDC, 2010b. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Hepatitis B general information. Available: 〈http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/PDFs/HepBGeneralFactSheet.pdf〉. (accessed October 16, 2013).

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), 2012. National Center for Health Statistics. Nchs research ethics review board (erb) approval. Available: 〈http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm〉 (accessed February 20, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2014a. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2011–2012 lab methods. Available: 〈http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2011-2012/lab_methods_11_12.htm〉 (accessed February 25, 2014).

- CDC, 2014b. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Available: 〈http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm〉 (accessed February 10, 2014).

- Choi B-S, Choi S-J, Kim D-W, Huang M, Kim N-Y, Park K-S, et al. , 2010. Effects of repeated seafood consumption on urinary excretion of arsenic species by volunteers. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 58 (1), 222–229. 10.1007/S00244-009-9333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangleben NL, Skibola CF, Smith MT, 2013. Arsenic immunotoxicity: a review. Environ. Health 12 (1), 73. 10.1186/1476-069X-12-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CM, Brooks WA, Graziano JH, Nonvane BA, Hossain L, Goswami D, et al. , 2015. Arsenic exposure is associated with pediatric pneumonia in rural Bangaldesh: a case control study. Environ. Health 14, 83. 10.1186/s12940-015-0069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert-Diamond D, Cottingham KL, Gruber JF, Punshon T, Sayarath V, Gandolfi AJ, et al. , 2011. Rice consumption contributes to arsenic exposure in US women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108 (51), 20656–20660. 10.1073/pnas.1109127108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein ST, Zhou F, Hadler SC, Bell BP, Mast EE, Margolis HS, 2005. A mathematical model to estimate global hepatitis B disease burden and vaccination impact. Int J. Epidemiol 34 (6), 1329–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney CD, Kmush B, Navas-Acien A, Francesconi K, Gössler W, Schulze K, et al. , 2015. Arsenic exposure and hepatitis E virus infection during pregnancy. Environ. Res 142, 273–280. 10.1016/j.envres.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich-Ramm R, Mindt-Prüfert S, Szadkowski D, 2002. Arsenic species excretion after controlled seafood consumption. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 778 (1–2), 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MR, Tellez-Plaza M, Vaidya D, Grau M, Francesconi KA, Goessler W, et al. , 2016. Estimation of inorganic arsenic exposure in populations with frequent seafood intake: evidence from MESA and NHANES. Am. J. Epidemiol 184 (8), 590–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kile ML, Houseman EA, Baccarelli A, Quamruzzaman Q, Rahman M, Mostofa G, et al. , 2014. Effect of prenatal arsenic exposure on DNA methylation and leukocyte subpopulations in cord blood. Epigenetics 9 (5), 774–782. 10.4161/epi.28153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koestler DC, Avissar-Whiting M, Houseman EA, Karagas MR, Marsit CJ, 2013. Differential DNA methylation in umbilical cord blood of infants exposed to low levels of arsenic in utero. Environ. Health Perspect 121 (8), 971–977. 10.1289/ehp.1205925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozul CD, Ely KH, Enelow RI, Hamilton JW, 2009. Low-dose arsenic compromises the immune response to influenza A infection in vivo. Environ. Health Perspect 117 (9), 1441–1447. 10.1289/ehp.0900911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Chouly C, Morzadec C, Bonvalet M, Galibert M-D, Fardel O, Vernhet L, 2011. Inorganic arsenic alters expression of immune and stress response genes in activated primary human T lymphocytes. Mol. Immunol 48 (6–7), 956–965. 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast EE, Margolis HS, Fiore AE, Brink EW, Goldstein ST, Wang SA, et al. , 2005. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm. Rep 54 (RR-16), 1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, Alter MJ, Bell BP, Finelli L, et al. , 2006. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) Part 2: immunization of adults. MMWR Recomm. Rep.: MMWR Recomm. Rep 8, 1–33 (55)(RR-16). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly CJ, Hampton TH, Brothers KM, Griffin NE, Planchart A, 2009. Perturbation of defense pathways by low-dose arsenic exposure in zebrafish embryos. Environ. Health Perspect 117 (6), 981–987. 10.1289/ehp.0900555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molin M, Ulven SM, Meltzer HM, Alexander J, 2015. Arsenic in human food chain, biotransformation and toxicology- Review focusing on seafood arsenic. J. Trace Elem. Med Biol 31, 249–259. 10.1016/j.jtemb.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naujokas MF, Anderson B, Ahsan H, Aposhian HV, Graziano JH, Thompson C, et al. , 2013. The broad scope of health effects from chronic arsenic exposure: update on a worldwide public health problem. Environ. Health Perspect 121, 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Acien, Francesconi KA, Silbergeld EK, Gualler E, 2011. Seafood intake and urine concentrations of total arsenic, dimethylarsinate and arsenobetaine in the US population. Environ. Res 111 (1), 110–118. 10.1016/j.envres.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak AS, Lage CR, Kim CH, 2007. Effects of low concentrations of arsenic on the innate immune system of the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol. Sci 98 (1), 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigra AE, Sanchez TR, Nachman KE, Harvey DE, Chilrud SN, Graziano JH, et al. , 2017. The effect of the Environmental Protection Agency maximum contaminant level on arsenic exposure in the USA from 2003 to 2014: an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Lancet Public Health 2, e513–e521. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvez F, Chen Y, Brandt-Rauf PW, Slavkovich V, Islam T, Ahmed A, et al. , 2010. A prospective study of respiratory symptoms associated with chronic arsenic exposure in Bangladesh: findings from the health effects of arsenic longitudinal study (HEALS). Thorax 65 (6), 528–533. 10.1136/thx.2009.119347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock ND, White JT, Cross EW, Cheney EE, Tamburini BA, Kedl RM, 2013. T cell responses: naïve to memory and everything in between. Adv. Physiol. Educ 37 (4), 273–283. 10.1152/advan.00066.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Vahter M, Ekström E-C, Persson L-Å, 2011. Arsenic exposure in pregnancy increases the risk of lower respiratory tract infection and diarrhea during infancy in Bangladesh. Environ. Health Perspect 119 (5), 719–724. 10.1289/ehp.1002265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raqib R, Ahmed S, Sultana R, Wagatsuma Y, Mondal D, Hoque A, et al. , 2009. Effects of in utero arsenic exposure on child immunity and morbidity in rural Bangladesh. Toxicol. Lett 185 (3), 197–202. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Jacques-Carroll L, Walker TY, Sirotkin B, Murphy TV, 2012. The national perinatal Hepatitis B prevention program, 1994–2008. Pediatrics 129 (4), 609–616. 10.1542/peds.2011-2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Peña GA, Luna AL, Acosta-Saavedra L, Conde P, López-Carrillo L, Cebrián ME, et al. , 2006. Assessment of lymphocyte subpopulations and cytokine secretion in children exposed to arsenic. FASEB J. 20 (6), 779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasley A, Kruszon-Moran D, Kuhnert W, Simard EP, Finelli L, McQuillan G, et al. , 2010. The prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States in the era of vaccination. J. Infect. Dis 202 (2), 192–201. 10.1086/653622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, Wang SA, Finelli L, Wasley A, et al. , 2008. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.