Pradip Dashraath and colleagues1 give recommendations about monkeypox exposure during pregnancy that do not fully align with public health guidance in the UK.

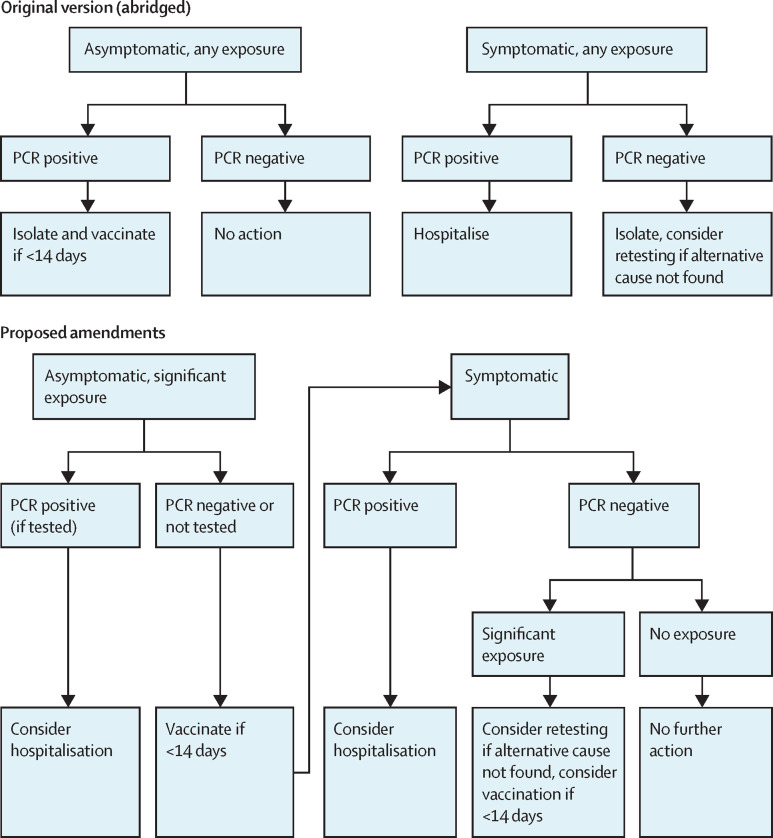

We propose a revision of the flowchart (figure ). As of August, 2022, the UK Health Security Agency no longer recommends self isolation for monkeypox contacts, although contacts at high risk (eg, after sexual exposure) are advised to avoid contact with clinically vulnerable people for 21 days.2 Precautionary admission to hospital should be considered for any pregnant person with a positive monkeypox PCR, regardless of symptoms. There is no benefit from vaccination after a positive monkeypox PCR test.

Figure.

Abridged screening flowchart proposed by Dashraath and colleagues1 and proposed amendments to flowchart to align with UK public health recommendations

The UK Health Security Agency recommends avoiding contact with immunosuppressed individuals, children younger than 5 years, and pregnant women for 21 days after significant exposure (direct monkeypox virus exposure to broken skin or mucous membranes), but does not recommend complete self isolation.2

Dashraath and colleagues1 list three types of monkeypox exposure: contact with a person who has human monkeypox; travel to an affected country; and exposure to exotic animals. The risk of monkeypox associated solely with travel is low: before 2022, eight travel-associated cases had been reported.3 Similarly, no zoonotic cases of monkeypox have been reported outside Africa since 2003.4

PCR testing of an oropharyngeal swab was recommended for asymptomatic, monkeypox-exposed pregnant women.1 In the UK, however, testing after exposure is not recommended unless symptoms are present.2 Oropharyngeal swabs are not 100% sensitive in early disease.3 If testing after exposure is done, orthopoxvirus serology tests should also be considered, if available.

In their proposed management plan for women who have been admitted to hospital, Dashraath and colleagues1 recommended prophylactic amoxicillin (systemic) and chloramphenicol (eye drops). We are unaware of evidence supporting prophylaxis against bacterial superinfection. In the analogous situation of chickenpox in pregnancy, prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended.5 The microbiome health of both mother and baby should be considered in this scenario, in addition to routine antimicrobial stewardship concerns.

Finally, we encourage the prospective documentation and analysis of all maternal and fetal outcomes after monkeypox exposure or illness in pregnancy, including the response to any antiviral therapies.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dashraath P, Nielsen-Saines K, Mattar C, Musso D, Tambyah P, Baud D. Guidelines for pregnant individuals with monkeypox virus exposure. Lancet. 2022;400:21–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01063-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UK Health Security Agency Monkeypox: contact tracing. Aug 9, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-contact-tracing

- 3.Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Inf Dis. 2022;22:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed KD, Melski JW, Graham MB, et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the western hemisphere. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Chickenpox in pregnancy. Green-top guideline no. 13. January, 2015. https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/y3ajgkda/gtg13.pdf