Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells, a crucial component of the innate immune system, have long been of clinical interest for their anti-tumor properties. Almost every aspect of NK cell immunity is regulated by interleukin-15 (IL-15), a cytokine in the common γ-chain family. Several current clinical trials are using IL-15 or its analogs to treat various cancers. Moreover, NK cells are being genetically modified to produce membrane-bound or secretory IL-15. Here, we discuss the key role of IL-15 signaling in NK cell immunity and provide an up-to-date overview of IL-15 in NK cell therapy.

Keywords: Interleukin-15, Natural killer cells, CAR NK cells, Cancer immunotherapy

IL-15 and NK cells: many unresolved questions

NK cells are well-known for their unique cytolytic effector function that does not require prior sensitization [1]. However, the cytokine(s) responsible for supporting NK cell development, survival, and activation evaded scientists until 1994, when two independent groups discovered IL-15 [2,3].

After the IL-15 signaling pathway was partially elucidated (Box 1, Figure 1), targeting it to further activate NK and CD8+ T cells became an exciting opportunity to potentially enhance cancer immunotherapy [4]. Administration of IL-15 and IL-15 agonists as a single agent has shown efficacy in preclinical murine tumor models, and clinical trials with these agents are currently being conducted for various types of cancers [4]. However, many unsolved or controversial issues remain regarding IL-15 and its pleiotropic effects. First, although IL-15 promotes the anti-tumor immunity mediated by NK cells and CD8+ T cells, certain tumor-promoting properties of IL-15 and/or IL-15/IL-15Rα have been noted in patients with leukemia or solid tumors [5–8]. Second, long-term or repeated exposure of NK cells to IL-15 results in NK cell hypo-responsiveness, which impairs NK cell survival, activation, cytotoxicity, and anti-tumor activity [9,10]. Third, IL-15 has at least four functional forms in humans in vivo: (1) soluble monomeric IL-15 (sIL-15), (2) the soluble IL-15/IL-15Rα complex, (3) trans-presented IL-15 (tpIL-15), and (4) membrane-bound IL-15 (mIL-15) [11–13]. Which forms of IL-15 are most abundant under physiological and pathological conditions is unclear, and the best IL-15 form for expanding NK cells in vivo has not been determined.

Box 1. IL-15 signaling in murine NK cells.

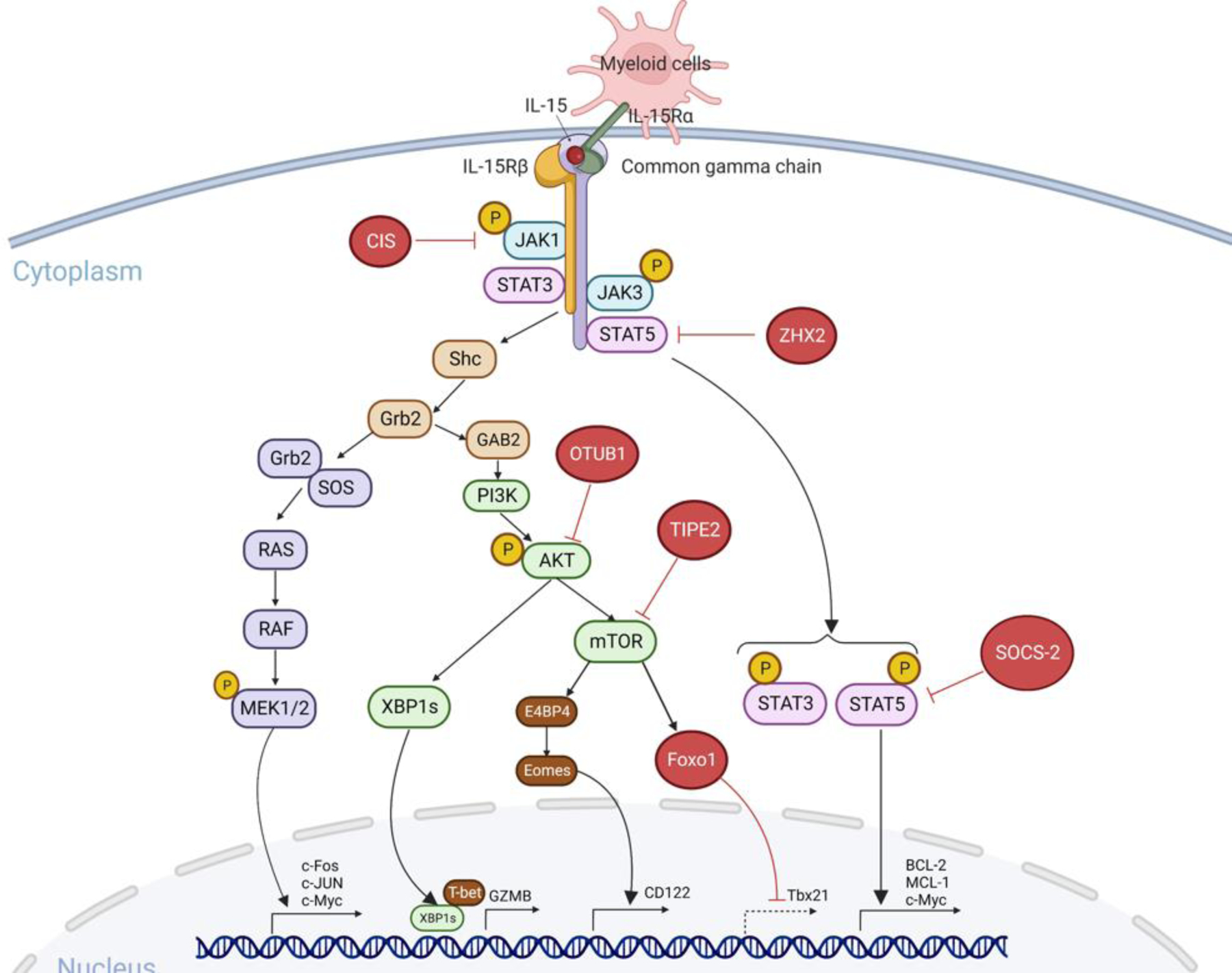

IL-15 belongs to the 4-α-helix bundle cytokine family, which includes IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-21. Both IL-15 and IL-2 bind to the heterodimeric IL-2/15Rβγc complex, but unlike IL-2, IL-15 does not utilize IL-2Rα [91]. This led to the discovery of a third IL-15 receptor component, IL-15Rα, [92,93]. IL-15 binds to IL-15Rα alone with high affinity (Ka ~1011 M−1) [92]. IL-15 also binds and signals through the heterodimeric IL-2/15Rβγ complex in the absence of the IL-15Rα chain, with intermediate affinity (Ka ~109 M−1) [91,94]. IL-15 is presented in-trans to NK cells expressing IL-2/15Rβγ to support NK cell development, survival, activation, and homeostasis [12,95,96]. IL-15 binding to the IL-2/15Rβγ receptor principally induces activation of JAK1, which subsequently phosphorylates STAT3 via the β chain and activates JAK3/STAT5 via the γc chain [97–99] (Figure 2, Key Figure). Phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT5 proteins translocate to the nucleus, where they activate transcription of the anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 [100] and MCL-1[101] and the oncogene c-Myc [102,103]. The homeostatic proliferation and survival of NK cells are fine-tuned by IL-15 signaling. At steady state, the extremely low concentrations of endogenous IL-15 primarily induce NK cell development in the bone marrow of mice and in secondary lymphoid tissue and other tissues of humans, and they maintain the survival of mature resting NK cells. However, a low concentration of endogenous IL-15 is largely insufficient to drive mature NK cells into division [44,104,105]. IL-15-mediated survival of NK cells is primarily regulated by the BCL-2 family, including BCL-2 and MCL-1 [100,101,106,107]. BCL-2 is highly expressed and regulates cell survival in resting NK cells, rather than when NK cells are in their activating or proliferating states [107]. A protein that is highly expressed throughout NK cell development, MCL-1, is regulated by IL-15-mediated STAT5 signaling and is essential for NK cell survival in both quiescent and proliferating states [106]. A newly identified signaling pathway, IL-15–AKT–XBP1s, was recently reported. XBP1s (X-box binding protein 1) is rarely expressed in resting NK cells but is highly expressed in IL-15-activated NK cells in humans [108]. XBP1s does not interact with endogenous STAT5 in human NK cells [108]. Knockdown of XBP1, using siRNAs, increased expression of cleaved caspase-3 in IL-15-activated human NK cells but not in resting human NK cells compared with cells transfected with scrambled siRNAs [108]. This pathway was therefore deemed independent of STAT5 signaling and thought to contribute to the survival of activated NK cells in humans, though this conclusion warrants further investigation. That study also showed that activated XBP1s is translocated into the nucleus, where it recruits T-bet, which induces transcription of genes encoding IFN-γ, granzyme B, and other molecules responsible for effector functions of NK cells [108]. From that study, we posit that incorporating XBP1s ectopic expression into genetically modified NK cells might benefit NK cell expansion, persistence, and effector function in vivo and argue that this approach merits further investigation.

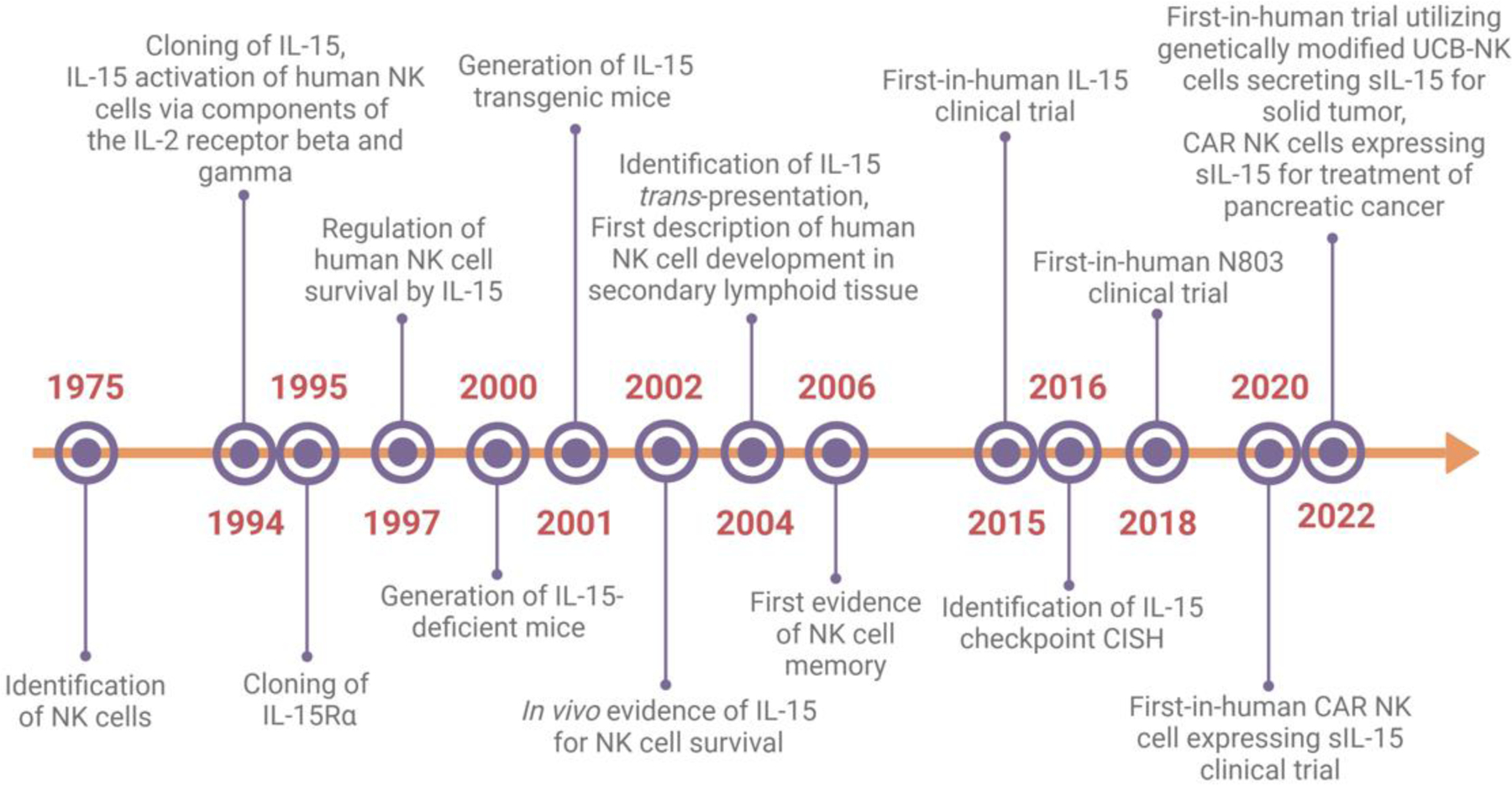

Figure 1. Timeline and major milestones in IL-15 and NK cell studies.

Abbreviations: CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; sIL-15, soluble IL-15; UCB, umbilical cord blood. Created with Biorender.com

Although IL-15 appears to be an attractive cytokine for treating cancer, its therapeutic usage can remain problematic. In this article, we discuss unanswered questions and review the role of IL-15 in cancer progression and NK cell immunity. We provide an up-to-date overview of existing and emerging investigations utilizing IL-15 for cancer immunotherapy. We also discuss potential approaches to reducing the untoward side effects of IL-15 administration and examine how IL-15 signaling might be redirected to potentiate the anti-tumor cytolytic activity of NK cells for successful immunotherapy.

IL-15 signaling in cancer: friend or foe?

As a potent proinflammatory cytokine, IL-15 promotes the proliferation and maintains the survival of certain T cells, such as CD8+ T cells, NKT cells, and γδT cells, and NK cells in both humans and mice [14,15]. However, it may also promote the growth of certain malignant cells that express all components of the IL-15 receptor, such as human T cell leukemia cells [16], cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) cells [5], large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia cells [17,18], and multiple myeloma (MM) cells [19]. Early studies using human tumor cell lines demonstrated that IL-15 can support in vitro growth of SeAx, a cell line of Sézary syndrome (an aggressive form of CTCL) and inhibit Fas-induced apoptosis in the MM cell lines IM-9, MC/CAR, and RPMI 8226 [5,19]. Intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of recombinant human (rh) IL-15 in nude mice harboring the human melanoma cell line MILG subcutaneously induces larger tumors compared with no rhIL-15 treatment [8]. These studies suggest that IL-15 might support cancer progression in vivo. Moreover, continued exposure to a supra-physiologic dose of IL-15 can also be detrimental. For instance, our group generated an IL-15 transgenic (Tg) (Il15Tg) mouse strain with constitutive overexpression of sIL-15 (mean ± SEM, 186.7 ± 41.8 pg/ml in serum) [6]. These mice displayed polyclonal expansion of their NK and NKT cells as well as of CD8+ memory T cell populations before 10 weeks of age. By weeks 15 to 25, ~30% of these IL-15Tg mice developed fatal lymphocytic leukemia with an NK or clonal NKT cell phenotype [6,20]. Similarly, mutated high mobility group protein I-C (HMGI-C) transgenic (Hmga2Tg) mice, which express excessive amounts of IL-2 and IL-15, develop NK or NKT cell lymphomas [21]. These studies support the notion that chronic inflammatory stimulation with IL-15 can increase the risk for malignant transformation of normal host cells [22]. Thus, chronic in vitro exposure of normal murine NK cells to IL-15 resulted in leukemic transformation after 6 months [23]. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of these cells into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice caused fatal leukemia in vivo [23]. Collectively, these observations suggest that IL-15 signaling can contribute to cancer progression.

Conversely, administration of IL-15 has been beneficial against primary and metastatic tumors in multiple mouse tumor models [24–27]. For instance, transducing the colon carcinoma cell line MC-38 with IL-15Rα enabled the cells to trans-present IL-15 to NK cells and augment their anti-tumor cytotoxicity activity, inhibiting MC-38 pulmonary metastases in vivo in mice [24]. Moreover, i.p. administration of recombinant murine (rm) IL-15 promoted anti-tumor activity associated with enhanced NK cell function in MC-38 and CT26 mouse colon cancer models, as evidenced by increased lytic activity and upregulated CD69 and granzyme B expression in NK cells [26]. A simultaneous comparison of tumor metastases among wild-type (WT), IL-15−/− (Il15−/−), IL-15Tg, and IL-15/IL-15Rα-treated mice (in the same model of metastatic breast cancer arising from the MT cell line) showed a high amount of metastasis in IL-15−/− mice but near-abolition of tumor metastases in IL-15Tg and IL-15-treated mice compared with WT mice [28]. In a spontaneous breast cancer model in which IL-15−/− or IL-15Tg mice were crossed with MMTV-PyMT mice, IL-15 deficiency increased tumor formation and decreased survival compared to WT mice. In contrast, the IL-15Tg and IL-15-treated mice had longer survival and fewer lung metastases [29]. Of note, antibody-mediated depletion of NK cells versus T cells in those studies suggested that NK cells, but not CD8+ T cells, were necessary for tumor destruction mediated by IL-15. This is an interesting observation because IL-15 has a stronger effect on NK cells than on CD8+ T cells during tumor metastasis [28,29]. Collectively, these studies suggest that IL-15 can systemically promote anti-tumor responses and be crucial for controlling tumor growth and metastases in vivo. They also suggest that IL-15’s role during tumor development is controversial. IL-15 induces leukemic transformation and acts as a growth factor for hematological tumor cells that express IL-15 receptors. However, it potentiates the anti-tumor immune response to suppress solid tumor progression and metastasis. Therefore, harnessing IL-15 for cancer immunotherapy should be considered with caution, and its suitability for a particular type of cancer must be carefully evaluated.

Although numerous cell types are important sources of IL-15, identifying those cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) remains elusive. Using IL-15 reporter mice, a recent study showed that the IL-15/IL-15Rα complex is abundant in several tumor models at an early stage but decreases with time in established B16 melanoma, MC-38 colon carcinoma, and MCA-205 mouse fibrosarcoma models [30]. Myeloid cells, specifically CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6G− cells, are the predominant sources of IL-15 within the TME [30], and restricting IL-15 expression to the TME is crucial for achieving optimal anti-tumor responses [31]. A comprehensive analysis of cytokine aberrations in a cohort of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients identified IL-15 as the key cytokine in the TME that associated with risk of cancer relapse. IL-15 loss resulted in a lower density of proliferating T and B cells within patient tumors [31]. Systemically delivered IL-15 induced the activation of non-tumor-specific T cells and NK cells, which resulted in off-tumor toxicity [32–34]. Moreover, CD8+ T cells activated by systemic administration of IL-15 were functionally compromised when they entered the TME, as evidenced by increased PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1) checkpoint expression [35]. Therefore, delivering IL-15 and/or its combination with immune-checkpoint inhibitors directly into a tumor might enable NK cells and CD8+ T cells to retain their anti-tumor activity [35,36]. In CT26 colon carcinoma or TRAMP-C2 prostatic cancer tumor models, tumor-bearing mice receiving IL-15 in combination with two anti-checkpoint antibodies (anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA4) showed reduced tumor growth and prolonged survival compared with those that received IL-15 alone [35,37]. IL-15 induces PD-L1 expression on NK cells, and anti–PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) enhances the anti-tumor effect of NK cells when administered in combination with IL-15 [36]. Indeed, this method of local sIL-15 delivery—trafficking NK cells directly into a tumor—in combination with anti-PD-L1 mAb checkpoint immunotherapy is currently being assessed in a phase I clinical trial (NCT05334329i). N-803 combined with anti-CD20 mAb showed a promising therapeutic effect in a phase I clinical trial of relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients (NCT02384954ii) [38]. This combination induced sustained proliferation, expansion, and activation of NK and CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood [38]. In addition, agonists such as stimulator of interferon genes (STING) can induce the release of endogenous IL-15 from myeloid cells to enhance NK cell anti-tumor immunity [39–42]. For instance, intra-tumoral injection of cyclic dinucleotide (CDN) promoted the proliferation, activation, and cytotoxicity of NK cells by inducing IL-15 and IL-15Rα on dendritic cells (DCs) in an RMA-B2m−/− mouse tumor model [39]. Of note, the STING agonist cGAMP (2′3′-Cyclic GMP-AMP) enhanced the sensitivity of AsPC-1 cells and Capan-2 pancreatic cancer cells to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-NK-92 cell cytotoxicity in vitro; a combination of cGAMP with CAR-NK-92 cells prolonged the survival of mice bearing AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer tumors [42].

In short, the role of IL-15 in tumor development and progression could be either favorable, ineffective, or detrimental, and it may depend on several factors, including the method, amount, timing, and/or location of delivery, as well as the type of tumor, etc. Despite some experimental evidence suggesting that it might be pro-tumorigenic in certain malignancies [5,11,16,18,19], IL-15 may be one of the most promising candidates for cell-mediated immunotherapy [43]. Moreover, it is important for NK cell development, proliferation, survival, and effector functions, as reviewed elsewhere [44–46]. Yet, our knowledge of IL-15 and its effects on NK cells as a lymphocytotrophic hormone and therapeutic agent remains incomplete. Therefore, understanding three distinct aspects—IL-15 form (Box 2), IL-15 dosage, and downstream IL-15 signaling (Key Figure, Figure 2)— and how each aspect regulates NK cell expansion, survival, and effector functions certainly merit further consideration.

Box 2. Forms of IL-15.

IL-15 mRNA is expressed constitutively in many cell types and tissues. However, IL-15 protein is undetectable in the majority of tissues in humans and mice [3]. IL-15 proteins are produced mainly by activated monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells [109–111]. Cancer cells, such as clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) cells and breast cancer cells, were recently reported to produce IL-15 to support the expansion and anti-tumor activity of type I innate lymphoid cells (ILC1s) [112], a subset of ILCs previously recognized as an NK cell subset [113]. IL-15/IL-15Rα treatment enhanced the cytotoxicity against target K562 cells of ILC1s isolated from ccRCC tumors; it also increased expression of the cell proliferation marker Ki67 [112]. IL-15Rα is distributed in a variety of immune and non-immune cells and tissues in humans and mice [92,93]. In humans, soluble (s) IL-15, sIL-15Rα, and the sIL-15/sIL-15Rα heterodimer are present in serum at very low concentrations under normal physiological conditions, but are upregulated in patients with cancer, including large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia [17], cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) [5], multiple myeloma (MM) [19], head and neck cancer [7], and metastatic melanoma [11]. As a single molecule, sIL-15 is undetectable in peripheral blood because it presents as a heterodimeric complex, sIL-15/IL-15Rα, in mice and humans [11]. rsIL-15 has a short half-life (from 2.5 to 12 hours depending on the administration route) in patients with advanced solid tumors, such as advanced metastatic melanoma (MM), RCC, non-small cell lung (NSCLC), and squamous cell head and neck carcinoma (SCCHN) [32,114]. To increase its in vivo half-life, several types of IL-15 agonists have been developed based on the mechanism of IL-15 trans-presentation [47]. The first one described was IL-15 N72D: IL-15RαSu/Fc, also known as N-803 (formerly ALT-803), an IL-15 complex of mutated IL-15 (N72D) noncovalently linked to the Sushi domain of IL-15Rα that is in turn fused to human immunoglobulin IgG1 Fc [47]. N-803 showed favorable pharmacokinetics in CD-1 mice (a strain that is commonly used in toxicology) and better ability to increase NK cell expansion in C57BL/6 mice when compared to single-chain sIL-15 [47]. Specifically, N-803 had an extended half-life in serum greater than that of rsIL-15 (~25 h vs. 0.64 h), and it induced higher NK cell proliferation than rsIL-15 at equimolar concentrations in vivo [47]. These observations suggest that the N-803 might be more therapeutically advantageous than IL-15 in the clinic, though this remains to be further investigated. Indeed, N-803 in combination with intra-vesicular Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) showed a promising result (71% complete response rate) in treating patients with BCG-unresponsive, high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NCT03022825vi).

Key Figure, Figure 2. Intracellular checkpoint of IL-15 signaling in human or murine NK cells.

IL-15 binds to the IL-15Rα expressed on antigen-presenting cells and then is presented in trans to IL-2/IL-15Rβγ heterodimer on NK cells [12]. IL-15 induces activation of JAK1/STAT3 via the β chain and JAK3/STAT5 via the γ chain [97–99]. Phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT5 proteins translocate to the nucleus where they activate transcription of the anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 [100] and MCL-1[101] and the oncogene c-Myc [102,103]. Activated adaptor protein Shc promotes Gab2 phosphorylation through the adaptor Grb2, and then induces the activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling [131]. XBP1 is induced by AKT and translocates to the nucleus, where it promotes GZMB expression [108]. mTORC1 drives the E4BP4-Eomes-CD122 pathway [132,133]. The third RAS-RAF-MAPK pathway induces the activation of c-Fos, c-Jun, and c-Myc, which promote NK cell proliferation [103]. There are also some intracellular checkpoints that negatively regulate IL-15 signaling. CIS interacts with JAK1 and inhibits its enzymatic activity [73]. ZHX2 blocks STAT5 activation [85]. SOCS-2 inhibits STAT5 phosphorylation [71]. OTUB1 inhibits AKT phosphorylation [81]. TIPE2 suppresses mTOR activity [83]. Foxo1 binds to the Tbx21 promoter and inhibits T-bet transcription [80]. Abbreviations: JAK, Janus kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1; GZMB, granzyme B; E4BP4, E4 promoter-binding protein 4; Eomes, eomesodermin; CIS, cytokine-inducible Src homology 2–containing protein; ZHX2, zinc fingers and homeoboxes; OTUB1, OTU domain-containing ubiquitin aldehyde-binding protein 1; TIPE2, tumor necrosis factor–α–induced protein-8 like-2; Foxo1, forkhead box o1. Created with Biorender.com

Forms of IL-15 (soluble, membrane-bound, and complexed IL-15)

Although the IL-15-IL-15Rα complex shows greater potency, bioavailability, and stability compared to recombinant soluble (rs)IL-15 when administered systemically to mice and humans [47–49], uncomplexed IL-15 is currently the most common form incorporated into genetically engineered CAR NK cells to extend NK cell survival in preclinical mouse models and clinical trials [50–52]. For instance, CD19 CAR NK cells derived from human umbilical cord blood (UCB) have been engineered to express sIL-15 for treating certain lymphoid malignancies in clinical trials (NCT03056339iii) [52]. CD33 CAR NK-92 cells were reported to be safe for treating relapsed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but less effective (NCT02944162iv) [53], likely because 1) the two types of CAR NK cells targeted different diseases and 2) the irradiated anti-CD33 CAR NK92 cells lacked sIL-15 and persisted for a shorter time in patients compared to UCB-derived CD19 CAR NK cells expressing sIL-15. In another study, IL-15 was produced predominantly by CD19 CAR NK cells in response to CD19+ targets; furthermore, CAR NK cells transduced with IL-15 proliferated at a similar rate as non-CAR NK cells when both were under in vitro expansion conditions, with IL-2 and K562 feeder cells expressing 4–1BBL and mIL-21. However, the IL-15-transduced CAR NK cells persisted longer in NOD-scid IL-2Rgammanull (NSG) mice in vivo, and they controlled tumor growth better than CAR NK cells that lacked sIL-15, as evidenced from reduced tumor volume and prolonged survival in a xenograft NSG mouse model of Raji lymphoma compared to control mice [50]. In the same model, i.p. administration of a low dose of rhIL-15 or CD19 CAR NK cells transduced to express sIL-15 were similarly able to (1) promote human CD19 CAR NK cell expansion and (2) control tumor progression, as evidenced by similar tumor burdens and survival rates. However, systemic low-dose i.p. administration of sIL-15 was associated with toxicity and treatment-related mortality [50]. This toxicity profile suggests that engineering CAR NK cells with sIL-15 might be a better alternative for supporting the proliferation, survival, and anti-tumor activity of CAR NK cells in vivo than administering IL-15 exogenously. This idea was subsequently supported in several other preclinical cancer models utilizing CAR NK cells, including models for AML [54–56], lymphoma [57], pancreatic cancer [51], and MM [55]. In one recent study, however, CAR-NK cells engineered to secrete sIL-15 caused early death in an immunodeficient mouse model engrafted with human MV-4–11 AML cells [56]. In that study, serum IL-15 concentration exceeded 1000 pg/ml [56], which was much higher than in other studies [50,51]. Therefore, though CAR NK cells engineered to express sIL-15 were reported to be safe in a clinical trial that used CD19 CAR NK cells to treat patients with relapsed or refractory CD19-positive cancers, additional robust preclinical and clinical trials are needed to gather more safety data. Further optimization of the constructs might safely regulate IL-15 secretion by genetically engineered NK cells. We recently reported the development of prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA)–CAR NK cells for pancreatic cancer [51]. In this model, the concentration of IL-15 in the cells’ supernatants was ~100 ng/ml, which did not induce systemic toxicity in NSG mice after either i.p. or intravenous (i.v.) administration. This observation suggests that CAR NK cells engineered to express relatively low concentrations of IL-15 should be safe in the clinic [51]. In fact, a clinical trial using NK cells genetically engineered to secrete low concentrations of sIL-15 was recently initiated for patients with refractory/relapsed non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (NCT05334329i).

Ideally, IL-15 would specifically activate NK cells and T cells within the TME. Recently, a tumor-conditional pro-IL-15 was produced by fusing the extracellular domain of IL-15Rβ into the N-terminus of IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc, using a tumor-enriched matrix metalloproteinase cleavable peptide linker [34]. This pro-IL-15 activates the expansion of NK and T cells in the TME but not in circulation, thus reducing systemic toxicity. It efficiently inhibited tumor growth in murine MC-38 colon cancer and A20 lymphoma models [34]. In addition, pro-IL-15 expanded intra-tumoral stem-like TCF1+Tim-3−CD8+ T cells and synergized with anti-PD-L1 mAb therapy in the MC-38 mouse colon cancer model [34]. However, other forms of IL-15 or targeted delivery of IL-15 into the TME remain to be explored. One study showed that human NK cells transduced with mIL-15 have autonomous survival and expansion capacity in the absence of IL-2 in vitro and in vivo in NSG mice [58]. Indeed, NK cells that expressed mIL-15 displayed increased cytotoxicity against K562 or U937 cells compared with mock-transduced NK cells [58]. Moreover, our group reported that an oncolytic virus expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα released the complex locally and could synergize with intra-tumoral injection of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-CAR NK cells to control tumor growth in multiple glioblastoma mouse models [59]. This observation suggests that targeted release of IL-15 within the TME may elicit strong anti-tumor activity in NK cells. Thus, exploring various forms of IL-15 for the purpose of sustaining and/or activating NK cells within the TME will need further investigation in pre-clinical and clinical settings to identify the best constructs for different clinical presentations. Recently, several multi-functional IL-15 agonists or fusion proteins (Box 3, Figure I) have been developed and are in pre-clinical evaluation.

Box 3. Multi-functional IL-15 agonists.

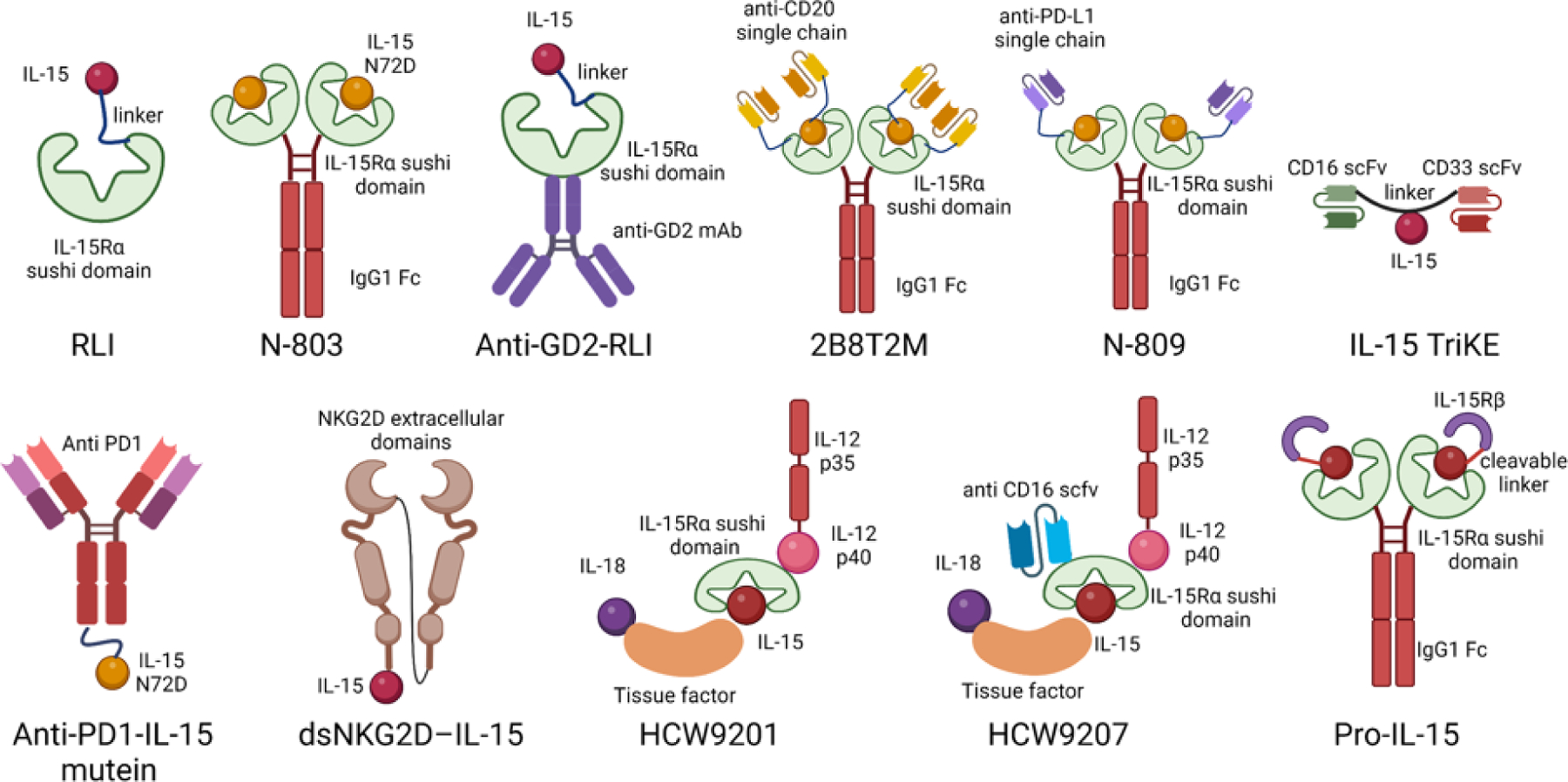

Several IL-15 agonists have been developed. These include IL-15N72D mutein [115], a heterodimer of IL-15 and IL-15Rα (hetIL-15) [48]; RLI, a fusion protein of IL-15 linked to the cytokine binding (Sushi) domain of IL-15Rα [116,117], and N-803, discussed earlier [47,118]. Some novel IL-15 agonists or fusion proteins are currently in the pre-clinical stage (Table 1 and Figure I). For instance, RLI has been fused to the heavy chain of an anti-GD2 ganglioside antibody (GD2-RLI). This anti-GD2-RLI fusion protein efficiently binds to GD2 (a tumor-associated antigen highly expressed on several tumors of neuroectodermal origin) and also binds to IL-15Rβγ; GD2-RLI inhibited tumor development in a mouse model of subcutaneous EL4 lymphomas and reduced liver metastasis of murine NXS2 neuroblastomas [119,120]. 2B8T2M (a fusion protein of N-803 and anti-CD20) is designed to simultaneously bind to CD20, IL-2/15Rβγc, and Fc receptors; 2B8T2M exhibited stronger anti-tumor activity than anti-CD20 monotherapy in a xenograft SCID mouse model [121]. N-803 has also been fused to an anti-PD-L1 mAb (designated N-809). N-809 blocks PD-L1 and induces IL-15-dependent immune effects [122]. Its subcutaneous administration induced anti-tumor efficacy in murine 4T1 breast and MC-38 colon carcinoma models [123]. A trispecific killer engager (TriKE) containing CD16 and CD33 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) and hIL-15 has also been developed. This IL-15 TriKE promoted in vivo persistence, activation, and survival of NK cells and showed better anti-tumor activity than CD16/CD33 BiKE in a xenografted human HL-60 AML model [124]. An IL-15 mutein (m) fused to a human PD1-specific mAb (anti-hPD1-IL15m) was reported recently. This immunocytokine was more effective than an IL-15 super-agonist when administered with an anti-mPD-1 mAb in the B16-F10 melanoma model. Anti-hPD1–IL15m targets mainly CD8+ T cells and induces the expansion of exhausted CD8+ T cells [125]. A double soluble (ds) NKG2D–IL-15 fusion protein was also recently reported; this protein consists of two identical extracellular domains of human NKG2D coupled to human IL-15 via a linker [126]. NKG2D–IL-15 exhibits higher anti-tumor efficiency than IL-15 in a xenografted human SGC-7901 gastric cancer model and mouse B16BL6–MICA melanoma model [126]. Recently, multifunctional heteromeric fusion protein complexes (HFPCs) comprised of IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 (referred to as HCW9201) or IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 with a CD16 ligation domain (HCW9207) were designed and produced [127]. HCW9201- and HCW9207-induced memory-like NK cells are similar to IL-12/15/18-induced memory-like NK cells, and the two equally improve cytotoxicity against K562 targets compared with IL-15 alone [127,128]. Therefore, HFPCs represent a potentially useful platform for producing multi-signal receptor engagement on immune cells. HCW9201 may become an ideal super-agonist for producing clinical GMP-grade memory-like NK cells for cancer therapy [129,130].

Figure I. in Box 3. IL-15 agonists and fusion proteins.

Top row, left to right: RLI is a fusion protein consisting of IL-15 linked to the cytokine binding (sushi) domain of IL-15Rα [116,117]. N-803 is an IL-15 complex comprising mutated IL-15 (N72D) linked to the sushi domain of IL-15Rα fused to human immunoglobulin IgG1 Fc [47,118]. Anti-GD2-RLI is a fusion protein comprising RLI and the heavy chain of an anti-GD2 ganglioside antibody [119,120]. 2B8T2M is a fusion protein consisting of N-803 and anti-CD20 [121]. N-809 is N-803 fused to an anti-PD-L1 antibody [122,123]. IL-15 trispecific killer engager (TriKE) is an engager containing CD16 and CD33 single-chain variable fragments (scFv) and hIL-15 linked by a fragment encoding G4S linker [124]. Anti-hPD1-IL15m is an IL-15 mutein fused with a human PD1-specific antibody [125]. dsNKG2D–IL-15 consists of two identical extracellular domains of human NKG2D coupled to human IL-15 via a linker [126]. HCW9201 is a heteromeric fusion protein complex comprising IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 [127]. HCW9207 is a heteromeric fusion protein complex containing IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, and a CD16 ligation domain [127]. Pro-IL-15 is the extracellular domain of IL-15Rβ fused into the N terminus of IL-15-IL-15Rα-Fc through a tumor-enriched matrix metalloproteinase cleavable peptide linker [34]. Created with Biorender.com

IL-15 dosage

In experimental systems such as IL-15Tg mice, long-term exposure to supra-physiological concentrations of IL-15 can trigger spontaneous T-NK and NK-LGL leukemia [6]. Moreover, sustained in vivo stimulation with the IL-15/IL-15Rα complex reduced proliferative capacity and decreased effector functions of NK cells in mice [9]. Similar results have been reported in human NK cells [10]. Also, continuous infusion of sIL-15 into humans changed the expression patterns of cell cycle and mitochondrial respiration genes in NK cells, resulting in more cell death, reduced CD107a degranulation and IFN-γ production, and decreased cytolytic activity against K562 cells and HL-60 cells [10]. Thus, NK cells become hyporesponsive after continuous stimulation with systemically administered sIL-15 or the sIL-15/IL-15Rα complex. For example, NK cells expanded less in response to a second infusion of sIL-15 in patients with advanced solid tumors such as metastatic melanoma, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), NSCLC, and squamous cell head and neck carcinoma (SCCHN) [32]. Also, repeated cycles of N-803 treatment in patients with NSCLC decreased NK cell proliferation and reduced serum IFN-γ concentrations compared with just one cycle [60]. Experimentally, NK cell hyporesponsiveness did not associate with the presence of suppressive CD4+ regulatory T cells, TGF-β, or IL-10, or with IL-15 competition between NK and T cells, because depleting CD25+ cells or treatments with anti–TGF-β or anti–IL-10R blocking Abs failed to restore the expansion of NK cells after two cycles of IL-15. However, the presence of pre-stimulated CD44+CD8+ T cells (as evidenced from adoptive transfer of these cells) inhibited NK cell expansion in mice, suggesting that these cells might affect NK cell expansion in vivo [61]. Of note, two early mouse studies showed that, compared to non-CD8+ T cell depletion, NK cells expanded more when CD8+ T cells were depleted by murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection or by a 3LL Lewis lung carcinoma cell challenge [62,63]. Depleting NK cells also expanded CD8+ T cells in vivo in a mouse model of 3LL Lewis lung carcinoma [63]. These data suggest two possibilities that require further investigation: 1) the two types of cytolytic immune cells—NK and CD8+ T cells—might mutually regulate each other in vivo; 2) with the removal of one of the IL-15 responsive populations, excess IL-15 might function on the remaining responsive population and induce their cell expansion. Recently, a group reported that N-803 administration induced the allo-rejection of CD8+ T cells, causing the elimination of haploidentical NK cells infused into patients with AML [64]. This study might help explain why systemic delivery of N-803 combined with adoptive haplo-NK cell therapy can produce worse clinical outcomes than adoptive haplo-NK cell therapy alone (NCT03050216v, NCT01898793vi). Presumably, N-803 treatment accelerates the rejection of donor NK cells that is mediated by host CD8+ T cells, suggesting that N-803 might act as a double-edged sword during haplo-NK cell therapy [65]. Although NK cells that are genetically modified to produce mIL-15 or sIL-15 can be sourced from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy allogeneic donors or donor UCB [66], it is still unclear whether more localized delivery of IL-15 might activate host CD8+ T cells and thereby cause the rejection of allogeneic donor NK cells. Rejection might partly depend on the dose of allogeneic NK cells per infusion, the sequence and timing of the infusions, and the provision of preconditioning immunosuppression to the patient. Of note, a prior study reported that CD56bright NK cells (a minor population of NK cells in the peripheral blood but abundant in secondary lymphoid tissues) showed potent anti-tumor activity against AML and MM and exhibited survival advantage in vivo compared to CD56dim NK cells following repeated N-803 priming [67]. Since an in vivo mouse study demonstrated that N-803 was accumulated mainly in lymphoid organs such as the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes [68], adoptively transferred allogeneic CD56bright NK cells combined with N-803 might have better therapeutic efficacythan CD56dim NK cells. Recently, a polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugate of rhIL-15 (NKTR-255) was designed for sustained release of IL-15 in vivo in SCID mice. In a xenograft SCID mouse model of Daudi lymphoma, NKTR-255 yielded therapeutic concentrations of IL-15 that persisted for days and showed potent anti-tumor efficacy, as evidenced by a longer half-life (15.2 h vs. 0.168 h) and longer survival compared with rhIL-15 [69,70]. NKTR-255 is currently being tested in clinical trials for both solid and hematological malignancies (NCT04136756vii, NCT04616196viii, NCT05359211ix, NCT03233854x).

Targeting the checkpoint of IL-15 signaling in NK cells

Another approach to enhancing the activity of genetically modified sIL-15 NK cells is to target the negative regulator or checkpoint of IL-15 signaling (Figure 2, Key Figure). The suppressor of cytokine (SOCS) family of proteins—including SOCS1, SOCS2, and cytokine-inducible Src homology 2–containing protein (CIS)—are key negative regulators of IL-15 signaling in mice [71]. Thus, SOCS1-deficient mice (Socs1−/−) harbored a larger number of CD8+CD44high memory T cells, which responded mainly to IL-15 signaling [72]. Also, NK cells from SOCS2-deficient (Socs2−/−) mice exhibited increased JAK2 and STAT5 phosphorylation following IL-15 stimulation [71]. Moreover, Socs2−/− mice had more NK cells and fewer lung metastases in a mouse model of B16-F10 melanoma [71]. Another protein, CIS, encoded by the CISH gene, is a potent intracellular checkpoint in NK cells downstream of IL-15 signaling [73,74]. CIS interacts with JAK1 to inhibit its enzymatic activity [73]. Deleting Cish in mice (Cish−/−) reduced NK cells’ hypersensitivity to IL-15, enhanced NK cell proliferation, survival, and IFN-γ production, and protected mice from lung metastasis in B16-F10 melanoma, RM-1 prostate cancer, and E0771 breast cancer [73] as well as from developing methylcholanthrene-induced fibrosarcoma [74]. A recent study showed that specific Cish-deletion from NK cells (Cishfl/fl Ncr1icre mice) increased their proliferation and IFN-γ and CD107a expression and suppressed tumor metastasis in mouse models of B16-F10 melanoma and E0771 breast cancer [75]. Of note, Cish-deletion (Cish−/−) protects against tumor metastasis, and that protection is NK cell- and IFN-γ-dependent and CD8+ T cell-independent because depleting CD8+ T cells in Cish−/− mice did not affect RM-1 lung metastases, whereas depleting NK cells or neutralizing IFN-γ abolished the effects of Cish deficiency [74]. In addition to demonstrating the inhibitory role of CIS in mediating IL-15 signaling, these data also support the notion that NK cells (known to traffic to lungs) can when activated, protect against cancers of the lung. It will be interesting to see if there is clinical benefit from the clinical study NCT05334329i, which is delivering activated NK cells secreting sIL-15 to patients with NSCLC. Moreover, Cish deficiency (Cish−/−) did not affect tumor growth in subcutaneous mouse models of B16-OVA melanoma or MC38-OVA colon cancer compared to WT mice [74]. Because such tumors are controlled by OVA-specific CD8+ T cells, these results suggest that Cish deficiency does not affect T cell-mediated tumor control. CIS therefore represents an interesting checkpoint that might be targeted to enhance NK cell anti-tumor activity. Indeed, a recent study found that a combination strategy—engineering NK cells to express IL-15, adding a CD19 CAR, and disrupting the CISH locus—enhanced the anti-tumor cytotoxic activity of the resulting IL-15/CD19-CAR NK cells in a mouse model of human Raji lymphoma [57]. Another checkpoint, E3 ubiquitin ligase casitas B cell lymphoma (Cbl)-b, is found in T cells [76]. Studies suggest it plays a negative role in activated mouse and human NK cells [77,78]. Indeed, NK cells from Cbl-b−/− mice produced more IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin than wildtype mice. Cbl-b deficiency also reduced lung metastases and increased survival in a mouse model of B16-F10 melanoma [78]. Knocking down CBL-B in human NK cells increased granzyme B, perforin, and IFN-γ production and boosted cytotoxicity against the AML cell lines MV4–11, MOLM-13, and EOL-1 [77]. Another group showed that silencing this inhibitory checkpoint molecule (using nanoparticles encapsulating small interfering RNA (siRNA)) enhanced NK cell degranulation in vitro and suppressed tumor growth in a xenograft SCID/NOD mouse model of 221.Cw4 B-cell lymphoma [79]. Moreover, the transcription factor FOXO1, whose phosphorylation is induced by IL-15 and other inflammatory cytokines as well as by tumor challenges, is a negative regulator of NK cells [80]. In vivo deletion of FOXO1 from NK cells, in Foxo1fl/fl Ncr1icre mice, led to increased maturation and enhanced effector functions, as evidenced from higher numbers of CD11b+CD27− terminally matured NK cells and greater IFN-γ production compared with littermate control mice [80]. OTU domain-containing ubiquitin aldehyde-binding protein 1 (OTUB1) was recently reported to be a checkpoint for IL-15-mediated priming in NK cells and CD8+ T cells in mice [81]. OTUB1 deubiquitinates AKT, inhibiting its phosphorylation and activation; T cell-specific Otub1 deficiency (Otub1fl/fl CD4icre mice) induced more CD8+ T cell proliferation and greater IFN-γ and TNF-α production in response to IL-15 [81]. Otub1 deficiency (Otub1fl/fl ROSA26-CreER mice) increased the number of terminally mature NK cells and enhanced the expression of granzyme B and chemokine C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) in NK cells [81]. Tumor necrosis factor–α–induced protein-8 like-2 (TIPE2) is essential for maintaining immune homeostasis by negatively regulating innate and adaptive immunity [82], and was recently reported to function as a potential intrinsic checkpoint molecule that suppresses IL-15–triggered mTOR activity in human and mouse NK cells [83]. Indeed, NK cell-specific TIPE2 deficiency (Tipe2fl/fl Ncr1icre mice) increased NK cell maturation, promoted NK cell effector functions, and enhanced NK cell responses to IL-15, as evidenced from higher numbers of CD11b+CD27− terminally matured NK cells, higher amounts of the activation marker CD69 and the effector cytokine IFN-γ, as well as higher cytolytic activity against YAC-1 cells when compared with control NK cells [83]. In addition, a recent study identified zinc fingers and homeoboxes 2 (ZHX2) (a ubiquitous transcriptional repressor [84]) as an intracellular checkpoint of NK cells that restricts NK cell maturation, survival, and effector functions by inhibiting STAT5 activation in mice [85]. Therefore, Cbl-b, FOXO1, OTUB1, TIPE2, and ZHX2 are all promising targets that might enhance NK cell-mediated anti-tumor activity. In addition, screening the genome-wide library of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 (Cas9) has been widely applied to find key regulators associated with specific cellular phenotypes [86–88]. It is likely that this technology and other methodologies can soon identify additional negative regulators of IL-15 signaling in NK cells. Together, these studies indicate that targeting a checkpoint of IL-15 signaling might be a potentially promising strategy for enhancing NK cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Therefore, further studies to explore new checkpoints of IL-15 signaling and strategies for inhibiting those checkpoint molecules are warranted.

Concluding remarks

Since the discovery of IL-15, >200 clinical trials have investigated several forms of IL-15 in cancer treatment. Thus, IL-15 has become a cytokine reagent of interest for cancer immunotherapy. As a single agent, however, it is limited by its pharmacokinetics and dose-dependent toxicity [4]. It is therefore likely that infusing therapeutically sufficient amounts of IL-15 without adding IL-15-dependent cells to act as a sink will produce off-target effects. Also, chronic stimulation of effector immune cells by IL-15 super-agonists can negatively affect the immune system, such as through NK and T cell exhaustion [9,10]. Combining IL-15 with an immune checkpoint blockade might improve therapeutic efficacy, but this remains to be rigorously assessed [35]. Reducing systemic toxicity while maintaining the anti-tumor activity of IL-15 is another direction we need to pursue. For example, using oncolytic virus or genetically modified NK cells might be a better way to locoregionally deliver therapeutic concentrations of IL-15 into the TME to induce potent anti-tumor efficacy. Thus, we posit that IL-15 might become a powerful weapon for treating cancer, but only after the mechanisms for tightly regulating it are deciphered, along with ways for combining it effectively with other cells or agents. Similar advances need to be made in understanding NK cell signaling to better incorporate IL-15 into NK-cell mediated immunotherapy.

Evidently, there are many questions about how to best improve NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy (see Outstanding Questions). Our incomplete understanding of the mechanisms by which IL-15 regulates NK cell immunity requires further robust basic studies. CRISPR-Cas9 screening should provide a powerful approach to identifying essential genes and downstream components of IL-15 signaling in NK cells. In addition, it is important for future clinical trials to optimize the forms of IL-15 used, the dosages, and the treatment schedules of IL-15 and IL-15 agonists, especially when they are combined with other agents, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, oncolytic viruses, CAR T cells, or CAR NK cells. Finally, by leveraging the latest advances in single-cell RNA sequencing and single-cell spatial sequencing [89,90], we might obtain multimodal measurements of individual cellular phenotypes and genotypes to better understand cell-to-cell communication within the TME in the absence and presence of IL-15 administration. A more comprehensive view of the immunosuppressive TME could also spur the development of more precise agents, including the various forms of IL-15 discussed here, to combat this formidable challenge to cancer immunotherapy.

Outstanding questions.

Is IL-15 the dominant factor maintaining NK cell survival and persistence in vivo? Are there unknown or known negative regulators, possibly downstream of IL-15, that regulate NK cell homeostasis?

How do we diminish the systemic toxicity of IL-15 infusion in cancer patients? How can we use IL-15 to specifically activate NK and CD8+ T cells within the TME without stimulating peripheral counterparts or inducing NK cell and/or T cell exhaustion?

How can we produce clinical quantities of CAR NK cells ex vivo, without jeopardizing their cellular functions (e.g., cytotoxicity and trafficking)? How long can sizeable numbers of CAR NK cells persist in patients with cancer?

Which form of IL-15 is the best simulator of CAR NK cell survival, activation, and persistence in vivo?

Could tumor-specific memory NK cells be manufactured, and might IL-15 play a role in this phenomenon?

Can IL-15 synergize with other agents, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, oncolytic viruses, or cancer vaccines, for successful cancer treatments?

Table 1.

In vivo studies of recent representative IL-15 agonists and fusion proteins.

| IL-15 Agent | Preclinical Tumor Models | Route and Dose | Effect and outcome | Species | Reference |

| Anti-GD2-RLI | EL4 lymphoma and NXS2 neuroblastoma | N/A | Inhibits EL4 and NXS2 tumor development and increases mouse survival. | Mouse | [119,120] |

| 2B8T2M | Daudi B-cell lymphoma | Intravenous injection (5 mg/kg) | Enhances ADCC and CDC against B-lymphoma; increases survival of SCID mice bearing Daudi B-lymphoma. | Mouse | [121] |

| N-809 | 4T1 lung metastasis and MC-38 colon cancer | Subcutaneous injection (25, 50, 100 μg per mouse) | Increases NK and CD8+ T cell activation, cytokine production, and infiltration. Decreases Treg cells and MDSCs. Inhibits 4T1 lung metastasis, decreases MC-38 tumor burden, and increases mouse survival. | Mouse | [122,123] |

| IL-15 TriKE | Human HL-60 AML model | Intraperitoneal injection (20 μg per mouse) | Promotes in vivo persistence, activation, and survival of NK cells and shows better anti-tumor activity than CD16/CD33 BiKE. | Mouse | [124] |

| Anti-PD1-IL-15 mutein | B16-F10 melanoma and MC-38 colon cancer | Subcutaneous injection (0.1, 0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg) | Induces the expansion of exhausted CD8+ T cells; enhances the proliferation, activation, and cytotoxicity of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, inhibits tumor growth in B16-F10 and MC-38 models. | Mouse | [125] |

| DsNKG2D-IL-15 | Human SGC-7901 gastric cancer and mouse B16BL6–MICA melanoma | Intraperitoneal injection (60 μg per mouse) | Enhances IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity of NK cells, inhibits growth of transplanted gastric cancer in nude mice. | Mouse | [126] |

| HCW9201, HCW9207 | K562 leukemia | Retroorbital injection of HCW9201 induced memory-like NK cells (5 million per mouse, three times per week) | HCW9201 and HCW9207 induced memory-like NK cells are similar to IL-12/15/18-induced memory-like NK cells and the two show equivalently improved cytotoxicity against K562 targets; improved mouse survival compared with control NK cells induced by IL-15 alone. | Mouse | [127] |

| Pro-IL-15 | MC-38 colon cancer and A20 lymphoma | Intravenous injection (0.2 nmol) | Pro-IL-15 does not activate the peripheral expansion of NK and T cells. It activates intratumoral CD8+ T cells and increases the stem-like TCF1+Tim-3−CD8+ T cells within tumor tissue. It inhibits tumor growth and synergizes with anti-PD-L1 mAb therapy in the MC-38 mouse colon cancer model. | Mouse | [34] |

Significance.

IL-15 and its combination with other reagent(s) are of interest in the field of cancer immunotherapy yet its potential untoward side effects have at times required special management. A better understanding of IL-15 signaling can improve its utilization for anti-tumor activity and ideally allow for successful NK cell-based immunotherapy.

Highlights.

IL-15 is a pleiotropic cytokine that promotes the survival, proliferation, and cytotoxicity of both NK and CD8+ T cells. As these cells take the lead in tumor destruction, the IL-15 pathway provides an exciting opportunity to enhance cancer cellular immunotherapy.

Like IL-2, IL-15 signals through a receptor complex composed of IL-2/IL-15 receptor beta (β) chain and the common gamma chain (γc). Unlike IL-2, however, IL-15 does not support activation-induced T cell death or enhance the proliferation, function, or differentiation of CD4+ regulatory T cells.

Administration of soluble (s) recombinant IL-15 and several IL-15 agonists has shown promising anti-tumor effects in preclinical murine models. These agents are currently under clinical investigation for treating hematological and solid tumor malignancies. sIL-15 and membrane-bound (m) IL-15 have also been genetically engineered into NK cells to enhance their survival, persistence, and activation in vivo.

Obtaining mechanistic insights into how IL-15 regulates NK cell immune responses and generating novel IL-15 agonists can help improve NK cell-based immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA210087, CA265095, and CA163205 to M.A.C.; NS106170, AI129582, CA247550, CA264512, and CA223400 to J.Y.) and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (1364–19 to J.Y.). The authors regret that it was not possible to include many other interesting studies in the field due to limited space.

Glossary

- Hypo-responsive NK cells

Pre-stimulated NK cells that can no longer respond to a second cycle of similar stimulation. Chronic IL-15 stimulation induces NK cell hypo-responsiveness.

- MMTV-PyMT mouse

genetically engineered mouse that contains the MMTV-PyVT transgene (which carries the polyoma virus middle T antigen, PyVT) and the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter (which drives mammary tissue-specific expression). MMTV-PyMT mice spontaneously develop mammary tumors.

- CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6G− cell

type of immature myeloid cell mononuclear morphology that exhibits suppressive capacity.

- Immune-checkpoint inhibitor

drug that blocks proteins called immune checkpoints (expressed on some types of immune cells, but also some tumor cells; e.g. PD-1 on T cells, PD-L1 on tumor cells). Blocking these checkpoints can uninhibit the cytotoxic effector functions of CD8+ T cells).

- STING

Stimulator of interferon genes, endoplasmic protein, a key component of the cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase)-STING pathway, which is a cellular cytosolic double-stranded DNA sensing pathway.

- CAR T cells

genetically engineered with a synthetic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) so they can recognize for example, specific tumor antigens independently of MHC-I expression.

- CAR NK cells

genetically engineered with CAR-expressing constructs.

- Oncolytic virus

native or genetically modified virus that can infect and destroy cancer cells.

- Haploidentical NK cells

NK cells from a donor who shares one human leukocyte antigen haplotype with the recipient.

- XBP1

transcription factor expressed during endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress that mediates the unfolded protein response (UPR).

- CRISPR-Cas9 screening

large-scale genetic perturbation screening with single-guide RNA (sgRNA) libraries for gene knockout, repression, and activation.

- GD2

disialoganglioside expressed on the surface of tumors of neuroectodermal origin, including human neuroblastoma and melanoma.

- NKG2D

activating receptor belonging to the NKG2 family of C-type lectin-like receptors; expressed on NK, NKT, CD8+ T, and γδT cells.

- MICA

MHC class I polypeptide–related sequence A; highly polymorphic cell surface glycoprotein that functions as a ligand for the activating receptor NKG2D.

- Single-cell RNA sequencing

technology that allows the information in messenger RNA to be decoded in single cells on a genomic scale.

- Single-cell spatial sequencing

genomic approach that measures gene expression profiles of individual cells, simultaneously taking their positional information into account.

- NK and T cell exhaustion

Production of effector cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ) wanes in NK or T cells, impairing their cytolytic activity. Exhausted NK cells or T cells usually downregulate their expression of activating receptors while upregulating their expression of inhibitory receptors.

- Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)

family of immune cells that mirror the phenotypes and functions of T cells, yet do not express antigen receptors or undergo clonal selection and expansion when stimulated. They include NK cells, ILC1s, ILC2s, ILC3s, and lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells.

- IL-15 trans-presentation

while most cytokines are secreted, IL-15 in dendritic cells and macrophages forms a complex with IL-15Rα. The complex is then shuttled to the surface of these accessory cells, which present it to the IL-2/15Rβγ receptor expressed on T and NK cells.

- Memory-like NK cells

have features resembling adaptive immunologic memory as they can remember prior cytokine exposure.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The two senior authors (Dr. Caligiuri and Dr. Yu) are co-founders of CytoImmnue Therapeutics, Inc. No other authors have a direct conflict of interest relevant to this research to declare.

Resources

References

- 1.Wolf NK et al. (2022) Roles of natural killer cells in immunity to cancer, and applications to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 10.1038/s41577-022-00732-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Grabstein KH et al. (1994) Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the beta chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science 264, 965–968. 10.1126/science.8178155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton JD et al. (1994) A lymphokine, provisionally designated interleukin T and produced by a human adult T-cell leukemia line, stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine-activated killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91, 4935–4939. 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldmann TA et al. (2020) IL-15 in the Combination Immunotherapy of Cancer. Front Immunol 11, 868. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobbeling U et al. (1998) Interleukin-15 is an autocrine/paracrine viability factor for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells. Blood 92, 252–258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fehniger TA et al. (2001) Fatal leukemia in interleukin 15 transgenic mice follows early expansions in natural killer and memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med 193, 219–231. 10.1084/jem.193.2.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badoual C et al. (2008) The soluble alpha chain of interleukin-15 receptor: a proinflammatory molecule associated with tumor progression in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 68, 3907–3914. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doucet C et al. (1997) Role of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-15 in the tumour progression of a melanoma cell line MELP, derived from an IL-2 progressor patient. Melanoma Res 7 Suppl 2, S7–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elpek KG et al. (2010) Mature natural killer cells with phenotypic and functional alterations accumulate upon sustained stimulation with IL-15/IL-15Ralpha complexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 21647–21652. 10.1073/pnas.1012128107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felices M et al. (2018) Continuous treatment with IL-15 exhausts human NK cells via a metabolic defect. JCI Insight 3. 10.1172/jci.insight.96219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergamaschi C et al. (2012) Circulating IL-15 exists as heterodimeric complex with soluble IL-15Ralpha in human and mouse serum. Blood 120, e1–8. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burkett PR et al. (2004) Coordinate expression and trans presentation of interleukin (IL)-15Ralpha and IL-15 supports natural killer cell and memory CD8+ T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med 200, 825–834. 10.1084/jem.20041389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giron-Michel J et al. (2005) Membrane-bound and soluble IL-15/IL-15Ralpha complexes display differential signaling and functions on human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood 106, 2302–2310. 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lodolce JP et al. (2002) Regulation of lymphoid homeostasis by interleukin-15. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 13, 429–439. 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00029-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becknell B and Caligiuri MA (2005) Interleukin-2, interleukin-15, and their roles in human natural killer cells. Adv Immunol 86, 209–239. 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86006-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada Y et al. (1998) Interleukin-15 (IL-15) can replace the IL-2 signal in IL-2-dependent adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) cell lines: expression of IL-15 receptor alpha on ATL cells. Blood 91, 4265–4272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J et al. (2012) Increased serum soluble IL-15Ralpha levels in T-cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Blood 119, 137–143. 10.1182/blood-2011-04-346759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R et al. (2008) Network model of survival signaling in large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 16308–16313. 10.1073/pnas.0806447105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tinhofer I et al. (2000) Expression of functional interleukin-15 receptor and autocrine production of interleukin-15 as mechanisms of tumor propagation in multiple myeloma. Blood 95, 610–618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu J et al. (2011) NKp46 identifies an NKT cell subset susceptible to leukemic transformation in mouse and human. J Clin Invest 121, 1456–1470. 10.1172/JCI43242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldassarre G et al. (2001) Onset of natural killer cell lymphomas in transgenic mice carrying a truncated HMGI-C gene by the chronic stimulation of the IL-2 and IL-15 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 7970–7975. 10.1073/pnas.141224998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greten FR and Grivennikov SI (2019) Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity 51, 27–41. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra A et al. (2012) Aberrant overexpression of IL-15 initiates large granular lymphocyte leukemia through chromosomal instability and DNA hypermethylation. Cancer Cell 22, 645–655. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi H et al. (2005) Role of trans-cellular IL-15 presentation in the activation of NK cell-mediated killing, which leads to enhanced tumor immunosurveillance. Blood 105, 721–727. 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang F et al. (2008) Activity of recombinant human interleukin-15 against tumor recurrence and metastasis in mice. Cell Mol Immunol 5, 189–196. 10.1038/cmi.2008.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang M et al. (2009) Interleukin-15 combined with an anti-CD40 antibody provides enhanced therapeutic efficacy for murine models of colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 7513–7518. 10.1073/pnas.0902637106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M et al. (2018) IL-15 enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mediated by NK cells and macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E10915–E10924. 10.1073/pnas.1811615115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillgrass A et al. (2014) The absence or overexpression of IL-15 drastically alters breast cancer metastasis via effects on NK cells, CD4 T cells, and macrophages. J Immunol 193, 6184–6191. 10.4049/jimmunol.1303175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillgrass AE et al. (2015) Overexpression of IL-15 promotes tumor destruction via NK1.1+ cells in a spontaneous breast cancer model. BMC Cancer 15, 293. 10.1186/s12885-015-1264-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santana Carrero RM et al. (2019) IL-15 is a component of the inflammatory milieu in the tumor microenvironment promoting antitumor responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 599–608. 10.1073/pnas.1814642116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mlecnik B et al. (2014) Functional network pipeline reveals genetic determinants associated with in situ lymphocyte proliferation and survival of cancer patients. Sci Transl Med 6, 228ra237. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller JS et al. (2018) A First-in-Human Phase I Study of Subcutaneous Outpatient Recombinant Human IL15 (rhIL15) in Adults with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 24, 1525–1535. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conlon KC et al. (2019) IL15 by Continuous Intravenous Infusion to Adult Patients with Solid Tumors in a Phase I Trial Induced Dramatic NK-Cell Subset Expansion. Clin Cancer Res 25, 4945–4954. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo J et al. (2021) Tumor-conditional IL-15 pro-cytokine reactivates anti-tumor immunity with limited toxicity. Cell Res 31, 1190–1198. 10.1038/s41422-021-00543-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu P et al. (2012) Simultaneous inhibition of two regulatory T-cell subsets enhanced Interleukin-15 efficacy in a prostate tumor model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 6187–6192. 10.1073/pnas.1203479109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong W et al. (2019) The Mechanism of Anti-PD-L1 Antibody Efficacy against PD-L1-Negative Tumors Identifies NK Cells Expressing PD-L1 as a Cytolytic Effector. Cancer Discov 9, 1422–1437. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu P et al. (2010) Simultaneous blockade of multiple immune system inhibitory checkpoints enhances antitumor activity mediated by interleukin-15 in a murine metastatic colon carcinoma model. Clin Cancer Res 16, 6019–6028. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foltz JA et al. (2021) Phase I Trial of N-803, an IL15 Receptor Agonist, with Rituximab in Patients with Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 27, 3339–3350. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicolai CJ et al. (2020) NK cells mediate clearance of CD8(+) T cell-resistant tumors in response to STING agonists. Sci Immunol 5. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz2738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcus A et al. (2018) Tumor-Derived cGAMP Triggers a STING-Mediated Interferon Response in Non-tumor Cells to Activate the NK Cell Response. Immunity 49, 754–763 e754. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esteves AM et al. (2021) Combination of Interleukin-15 With a STING Agonist, ADU-S100 Analog: A Potential Immunotherapy for Prostate Cancer. Front Oncol 11, 621550. 10.3389/fonc.2021.621550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Da Y et al. (2022) STING agonist cGAMP enhances anti-tumor activity of CAR-NK cells against pancreatic cancer. Oncoimmunology 11, 2054105. 10.1080/2162402X.2022.2054105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheever MA (2008) Twelve immunotherapy drugs that could cure cancers. Immunol Rev 222, 357–368. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huntington ND (2014) The unconventional expression of IL-15 and its role in NK cell homeostasis. Immunol Cell Biol 92, 210–213. 10.1038/icb.2014.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rautela J and Huntington ND (2017) IL-15 signaling in NK cell cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol 44, 1–6. 10.1016/j.coi.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X and Zhao XY (2021) Transcription Factors Associated With IL-15 Cytokine Signaling During NK Cell Development. Front Immunol 12, 610789. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.610789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han KP et al. (2011) IL-15:IL-15 receptor alpha superagonist complex: high-level co-expression in recombinant mammalian cells, purification and characterization. Cytokine 56, 804–810. 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chertova E et al. (2013) Characterization and favorable in vivo properties of heterodimeric soluble IL-15.IL-15Ralpha cytokine compared to IL-15 monomer. J Biol Chem 288, 18093–18103. 10.1074/jbc.M113.461756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubinstein MP et al. (2022) Phase I Trial Characterizing the Pharmacokinetic Profile of N-803, a Chimeric IL-15 Superagonist, in Healthy Volunteers. J Immunol 208, 1362–1370. 10.4049/jimmunol.2100066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu E et al. (2018) Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia 32, 520–531. 10.1038/leu.2017.226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teng KY et al. (2022) Off-the-Shelf Prostate Stem Cell Antigen-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor Natural Killer Cell Therapy to Treat Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 162, 1319–1333. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu E et al. (2020) Use of CAR-Transduced Natural Killer Cells in CD19-Positive Lymphoid Tumors. N Engl J Med 382, 545–553. 10.1056/NEJMoa1910607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang X et al. (2018) First-in-man clinical trial of CAR NK-92 cells: safety test of CD33-CAR NK-92 cells in patients with relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Cancer Res 8, 1083–1089 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Du Z et al. (2021) piggyBac system to co-express NKG2D CAR and IL-15 to augment the in vivo persistence and anti-AML activity of human peripheral blood NK cells. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 23, 582–596. 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X et al. (2020) Inducible MyD88/CD40 synergizes with IL-15 to enhance antitumor efficacy of CAR-NK cells. Blood Adv 4, 1950–1964. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christodoulou I et al. (2021) Engineering CAR-NK cells to secrete IL-15 sustains their anti-AML functionality but is associated with systemic toxicities. J Immunother Cancer 9. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daher M et al. (2021) Targeting a cytokine checkpoint enhances the fitness of armored cord blood CAR-NK cells. Blood 137, 624–636. 10.1182/blood.2020007748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imamura M et al. (2014) Autonomous growth and increased cytotoxicity of natural killer cells expressing membrane-bound interleukin-15. Blood 124, 1081–1088. 10.1182/blood-2014-02-556837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma R et al. (2021) An Oncolytic Virus Expressing IL15/IL15Ralpha Combined with Off-the-Shelf EGFR-CAR NK Cells Targets Glioblastoma. Cancer Res 81, 3635–3648. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wrangle JM et al. (2018) ALT-803, an IL-15 superagonist, in combination with nivolumab in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol 19, 694–704. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30148–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frutoso M et al. (2018) Emergence of NK Cell Hyporesponsiveness after Two IL-15 Stimulation Cycles. J Immunol 201, 493–506. 10.4049/jimmunol.1800086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salem ML and Hossain MS (2000) In vivo acute depletion of CD8(+) T cells before murine cytomegalovirus infection upregulated innate antiviral activity of natural killer cells. Int J Immunopharmacol 22, 707–718. 10.1016/s0192-0561(00)00033-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alvarez M et al. (2014) Increased antitumor effects using IL-2 with anti-TGF-beta reveals competition between mouse NK and CD8 T cells. J Immunol 193, 1709–1716. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berrien-Elliott MM et al. (2022) Systemic IL-15 promotes allogeneic cell rejection in patients treated with natural killer cell adoptive therapy. Blood 139, 1177–1183. 10.1182/blood.2021011532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pende D and Meazza R (2022) N-803: a double-edged sword in haplo-NK therapy. Blood 139, 1122–1124. 10.1182/blood.2021014789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yilmaz A et al. (2020) Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered natural killer cells for cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol 13, 168. 10.1186/s13045-020-00998-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wagner JA et al. (2017) CD56bright NK cells exhibit potent antitumor responses following IL-15 priming. J Clin Invest 127, 4042–4058. 10.1172/JCI90387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rhode PR et al. (2016) Comparison of the Superagonist Complex, ALT-803, to IL15 as Cancer Immunotherapeutics in Animal Models. Cancer Immunol Res 4, 49–60. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0093-T [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyazaki T et al. (2021) NKTR-255, a novel polymer-conjugated rhIL-15 with potent antitumor efficacy. J Immunother Cancer 9. 10.1136/jitc-2020-002024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Robinson TO et al. (2021) NKTR-255 is a polymer-conjugated IL-15 with unique mechanisms of action on T and natural killer cells. J Clin Invest 131. 10.1172/JCI144365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Kim WS et al. (2017) Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 2 Negatively Regulates NK Cell Differentiation by Inhibiting JAK2 Activity. Sci Rep 7, 46153. 10.1038/srep46153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davey GM et al. (2005) SOCS-1 regulates IL-15-driven homeostatic proliferation of antigen-naive CD8 T cells, limiting their autoimmune potential. J Exp Med 202, 1099–1108. 10.1084/jem.20050003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Delconte RB et al. (2016) CIS is a potent checkpoint in NK cell-mediated tumor immunity. Nat Immunol 17, 816–824. 10.1038/ni.3470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Putz EM et al. (2017) Targeting cytokine signaling checkpoint CIS activates NK cells to protect from tumor initiation and metastasis. Oncoimmunology 6, e1267892. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1267892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bernard PL et al. (2022) Targeting CISH enhances natural cytotoxicity receptor signaling and reduces NK cell exhaustion to improve solid tumor immunity. J Immunother Cancer 10. 10.1136/jitc-2021-004244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chiang YJ et al. (2000) Cbl-b regulates the CD28 dependence of T-cell activation. Nature 403, 216–220. 10.1038/35003235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lu T et al. (2021) Cbl-b Is Upregulated and Plays a Negative Role in Activated Human NK Cells. J Immunol 206, 677–685. 10.4049/jimmunol.2000177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paolino M et al. (2014) The E3 ligase Cbl-b and TAM receptors regulate cancer metastasis via natural killer cells. Nature 507, 508–512. 10.1038/nature12998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biber G et al. (2022) Modulation of intrinsic inhibitory checkpoints using nano-carriers to unleash NK cell activity. EMBO Mol Med 14, e14073. 10.15252/emmm.202114073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deng Y et al. (2015) Transcription factor Foxo1 is a negative regulator of natural killer cell maturation and function. Immunity 42, 457–470. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou X et al. (2019) The deubiquitinase Otub1 controls the activation of CD8(+) T cells and NK cells by regulating IL-15-mediated priming. Nat Immunol 20, 879–889. 10.1038/s41590-019-0405-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sun H et al. (2008) TIPE2, a negative regulator of innate and adaptive immunity that maintains immune homeostasis. Cell 133, 415–426. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bi J et al. (2021) TIPE2 is a checkpoint of natural killer cell maturation and antitumor immunity. Sci Adv 7, eabi6515. 10.1126/sciadv.abi6515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu Y et al. (2015) Zinc fingers and homeoboxes family in human diseases. Cancer Gene Ther 22, 223–226. 10.1038/cgt.2015.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tan S et al. (2021) Transcription factor Zhx2 restricts NK cell maturation and suppresses their antitumor immunity. J Exp Med 218. 10.1084/jem.20210009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Joung J et al. (2017) Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout and transcriptional activation screening. Nat Protoc 12, 828–863. 10.1038/nprot.2017.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shifrut E et al. (2018) Genome-wide CRISPR Screens in Primary Human T Cells Reveal Key Regulators of Immune Function. Cell 175, 1958–1971 e1915. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Long L et al. (2021) CRISPR screens unveil signal hubs for nutrient licensing of T cell immunity. Nature 600, 308–313. 10.1038/s41586-021-04109-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marx V (2021) Method of the Year: spatially resolved transcriptomics. Nat Methods 18, 9–14. 10.1038/s41592-020-01033-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schier AF (2020) Single-cell biology: beyond the sum of its parts. Nat Methods 17, 17–20. 10.1038/s41592-019-0693-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carson WE et al. (1994) Interleukin (IL) 15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J Exp Med 180, 1395–1403. 10.1084/jem.180.4.1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Giri JG et al. (1995) Identification and cloning of a novel IL-15 binding protein that is structurally related to the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. EMBO J 14, 3654–3663. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00035.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Anderson DM et al. (1995) Functional characterization of the human interleukin-15 receptor alpha chain and close linkage of IL15RA and IL2RA genes. J Biol Chem 270, 29862–29869. 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Giri JG et al. (1994) Utilization of the beta and gamma chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J 13, 2822–2830. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koka R et al. (2003) Interleukin (IL)-15R[alpha]-deficient natural killer cells survive in normal but not IL-15R[alpha]-deficient mice. J Exp Med 197, 977–984. 10.1084/jem.20021836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koka R et al. (2004) Cutting edge: murine dendritic cells require IL-15R alpha to prime NK cells. J Immunol 173, 3594–3598. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Johnston JA et al. (1995) Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT5, STAT3, and Janus kinases by interleukins 2 and 15. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 92, 8705–8709. 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miyazaki T et al. (1994) Functional activation of Jak1 and Jak3 by selective association with IL-2 receptor subunits. Science 266, 1045–1047. 10.1126/science.7973659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lin JX et al. (1995) The role of shared receptor motifs and common Stat proteins in the generation of cytokine pleiotropy and redundancy by IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-13, and IL-15. Immunity 2, 331–339. 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Carson WE et al. (1997) A potential role for interleukin-15 in the regulation of human natural killer cell survival. J Clin Invest 99, 937–943. 10.1172/JCI119258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huntington ND et al. (2007) Interleukin 15-mediated survival of natural killer cells is determined by interactions among Bim, Noxa and Mcl-1. Nat Immunol 8, 856–863. 10.1038/ni1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lord JD et al. (2000) The IL-2 receptor promotes lymphocyte proliferation and induction of the c-myc, bcl-2, and bcl-x genes through the trans-activation domain of Stat5. J Immunol 164, 2533–2541. 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Miyazaki T et al. (1995) Three distinct IL-2 signaling pathways mediated by bcl-2, c-myc, and lck cooperate in hematopoietic cell proliferation. Cell 81, 223–231. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90332-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ranson T et al. (2003) IL-15 is an essential mediator of peripheral NK-cell homeostasis. Blood 101, 4887–4893. 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Huntington ND et al. (2007) NK cell maturation and peripheral homeostasis is associated with KLRG1 upregulation. J Immunol 178, 4764–4770. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sathe P et al. (2014) Innate immunodeficiency following genetic ablation of Mcl1 in natural killer cells. Nat Commun 5, 4539. 10.1038/ncomms5539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Viant C et al. (2017) Cell cycle progression dictates the requirement for BCL2 in natural killer cell survival. J Exp Med 214, 491–510. 10.1084/jem.20160869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]