Abstract

Objective: This study assessed the regional disparities and the associated factors in the implementation of cardiac rehabilitation in Japan.

Materials and Methods: Regional disparities were investigated by comparing the number of cardiac rehabilitation units in each of 47 prefectures in Japan based on the National Database of Health Insurance Claims Open Data published by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. The relationships between the numbers of inpatient and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation units and the numbers of registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation, board-certified physiatrists, and board-certified cardiologists were examined.

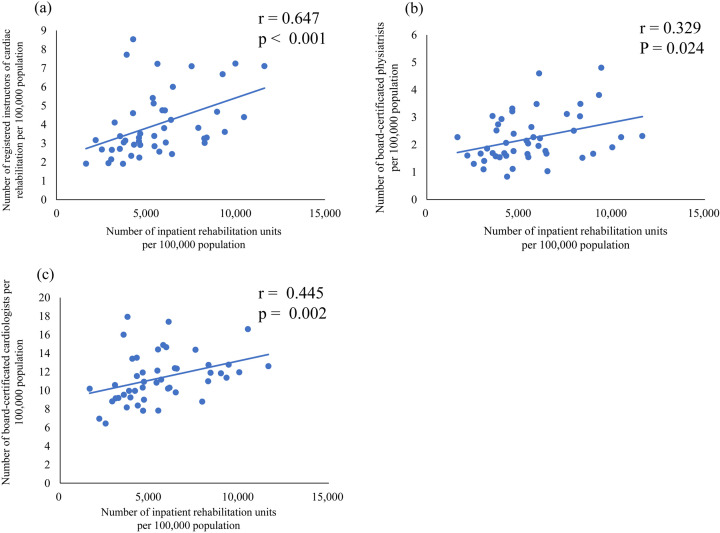

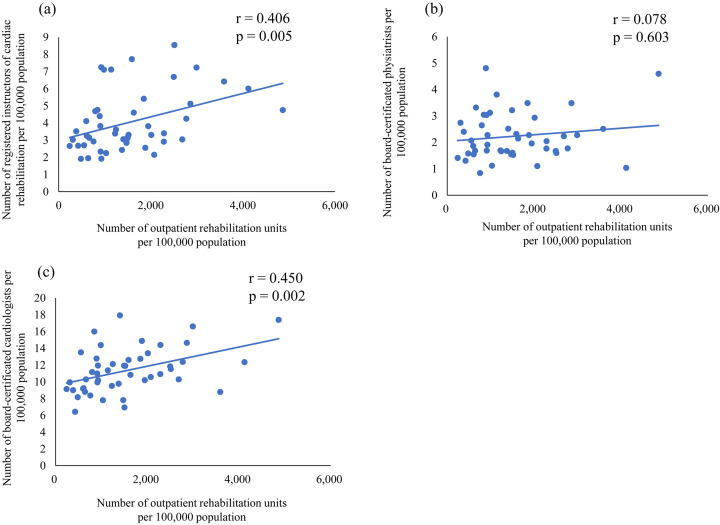

Results: The region with the highest and lowest numbers of inpatient units showed 11,620.5 and 1,650.2 population-adjusted cardiac rehabilitation units adjusted per 100,000 population, respectively, corresponding to a 7.0-fold difference. Meanwhile, 4,865.3 and 238.6 units were present in the regions with the highest and lowest numbers of outpatient units, respectively, corresponding to a 20.4-fold regional disparity. Our analysis showed that the population-adjusted number of inpatient cardiac rehabilitation units was significantly associated with the population-adjusted numbers of registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation (r=0.647, P<0.001) and board-certified cardiologists (r=0.445, P=0.002) but only marginally associated with the population-adjusted number of board-certified physiatrists (r=0.329, P=0.024). Moreover, the population-adjusted number of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation units was significantly associated with the population-adjusted numbers of registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation (r=0.406, P=0.005) and board-certified cardiologists (r=0.450, P=0.002) but not with the population-adjusted number of board-certified physiatrists (r=0.078, P=0.603).

Conclusion: Large regional disparities were observed during the implementation of cardiac rehabilitation. Increased numbers of cardiac rehabilitation instructors and cardiac rehabilitation practices are expected to eliminate these regional differences in cardiac rehabilitation practices.

Keywords: cardiac rehabilitation, regional disparity, registered instructor of cardiac rehabilitation

Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR), an effective treatment for cardiac diseases1), is designed to promote a healthy and active lifestyle and improve patient quality of life (QOL) by increasing exercise tolerance; decreasing cardiovascular symptoms; reducing anxiety, depression, and stress; enabling a return to work; and helping people to maintain independence in their activities of daily living2,3,4). CR reduces mortality by up to 25%, improves functional capacity, and decreases the risk of rehospitalization3, 4).

However, a 2004 nationwide survey in Japan showed that the rate of CR in the recovery phase after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was as low as 20%5), suggesting the presence of an evidence-practice gap in CR caused by concerns related to patients, healthcare providers, and the system (environment)3). The factors associated with patient participation in CR include a lack of awareness regarding the importance of CR6), marital status6), depression and chronic diseases7), sex8, 9), and age9). Similarly, the factors related to CR provision based on reports by health care providers include a lack of awareness of CR6) and interventions aimed at motivating and providing information regarding CR to patients9). Systemic (environmental) factors affecting CR participation include the scheduling availability of CR8), hospital accessibility6), availability of parking at the hospital8), facility location, availability of public transportation8, 9), and lack of system construction that satisfies individual needs10).

Two-thirds of Japan’s landscape consists of mountainous areas, which may affect the population distribution. Moreover, uneven population distributions may cause disparities in the number of medical facilities, quality of medical care, and number of medical staff. Despite the potential regional disparities in CR implementation, regional disparities in the number of CR units and their relationship to the number of medical staff involved in CR remain unclear.

Therefore, this study examined regional disparities in CR implementation throughout Japan and the human resource factors associated with these disparities. The information obtained from this study provides basic data necessary for establishing medical policies for cardiovascular diseases.

Materials and Methods

Open data

The populations of each prefecture were determined based on census data from October 1, 2017, from the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications11). This study used open data from the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups (NDB)12), which has been maintained by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare since 2008. The NDB open dataset contains information on >20 million health insurance claims and specific health checkups annually and has been providing data to researchers and government agencies since 2011.

The cardiac rehabilitation units were extracted from the total number of rehabilitation units in the NDB data. Inpatient and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation units at authorized insurance medical institutions that had submitted a notification to the Director of the Regional Health and Welfare Bureau and met the facility standards specified by the Minister of Health, Labour, and Welfare were assessed. These units can be assessed when exercise therapy is performed, based on an appropriate exercise prescription following an evaluation of cardiopulmonary function to restore cardiac function and prevent disease recurrence.

Cardiac rehabilitation personnel

This study assessed three cardiac rehabilitation personnel: registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation (RICRs), board-certified physiatrists (BCPs), and board-certified cardiologists (BCCs). The Japanese Society of Cardiac Rehabilitation established the RICR system in Japan in 2000. As of 2020, there have been 4,474 certified RICRs13), who aim to treat cardiovascular diseases, reduce readmissions, prevent recurrence, and improve QOL through comprehensive CR, including the prevention of deconditioning and weaning after acute myocardial infarction (AMI), exercise therapy for patients with heart failure (HF), early weaning and early discharge after cardiovascular surgery, lifestyle guidance, nutritional guidance, and medication guidance13). Physicians, nurses, physical therapists, clinical laboratory technicians, registered dietitians, pharmacists, clinical engineering technicians, clinical psychologists, licensed psychologists, occupational therapists, or health and exercise instructors can be certified as a RICR after 2 years of membership in the Japanese Society of Cardiac Rehabilitation, submitting a case report, and passing the certification examination.

As of 2021, the Japanese Association of Rehabilitation Medicine has employed 2,612 BCPs14). The requirements for becoming a BCP of the Japanese Association of Rehabilitation Medicine include a 3-year residency program that covers the entire field of rehabilitation medicine, followed by final written and oral examinations. BCPs in Japan must renew their certification every 5 years.

In 2019, the Japanese Circulation Society certified 15,168 BCCs15). After obtaining a medical license, physicians can apply to become a BCC by completing at least 6 years of clinical experience, including 3 years of training at a facility authorized by the Japanese Society of Cardiology.

Data description

Using NDB open data from 2017, we examined the number of inpatient and outpatient CR units and regional differences in the numbers of inpatient or outpatient CR units per 100,000 population throughout each Japanese prefecture, as well as the relationships between the population-adjusted number of cardiac rehabilitation personnel (RICRs, BCPs, and BCCs) per 100,000 population and the population-adjusted number of CR units. The correlations between the population-adjusted numbers of cardiac rehabilitation personnel (RICRs, BCPs, and BCCs) and the numbers of population-adjusted inpatient and outpatient CR units were examined.

Map creation

The regional distribution of the number of RICRs, BCPs, and BCCs and the numbers of inpatient and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation units per 100,000 population in 47 prefectures in Japan were mapped using the Excel map coloring function.

Statistical analysis

The numbers of population-adjusted inpatient and outpatient CR units, RICRs, BCPs, and BCCs per prefecture were expressed as medians (interquartile range [IQR]). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient analysis was used to examine the associations between the numbers of RICRs, BCPs, and BCCs, and the numbers of inpatient and outpatient CR units. Regional disparities were identified by obtaining the maximum and minimum numbers of CR units from the NDB open data for all 47 prefectures and dividing the maximum by the minimum. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with the threshold for significance set at P<0.05.

Results

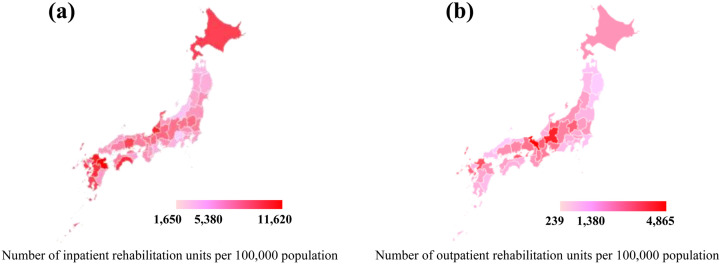

Each prefecture had a median of 5,380.6 (IQR 3,846.3–6,507.3) inpatient CR units, with the largest and smallest regions having 11,620.5 and 1,650.2 units, respectively, resulting in a 7.0-fold regional disparity (Table 1). Each prefecture had a median of 1,372.2 (IQR 795.3–2,074.9) outpatient CR units, ranging from 4,865.3 and 238.6 units, corresponding to a 20.4-fold disparity among regions (Table 1).

Table 1. Population-adjusted numbers of inpatient and outpatient units per 100,000 population per 47 in each of prefectures.

| Minimum | Median (IQR) | Maximum | Regional disparity (Maximum/minimum) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of inpatient rehabilitation units per 100,000 population | 1,650.2 | 5,380.6 (3,846.3–6,507.3) | 11,620.5 | 7.0 |

| Number of outpatient rehabilitation units per 100,000 population | 238.6 | 1,372.2 (795.3–2,074.9) | 4,865.3 | 20.4 |

IQR: interquartile range.

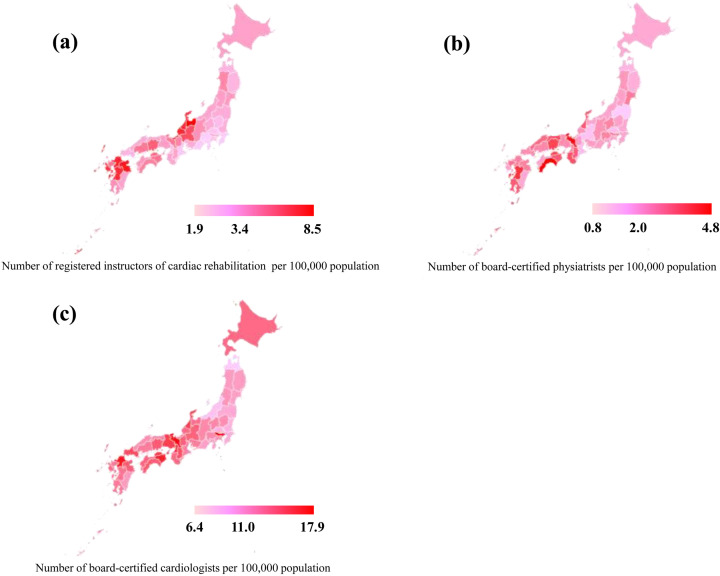

Each prefecture had a median of 3.4 (IQR 2.8–4.8) RICRs, ranging from 8.5 to 1.9 RICRs and corresponding to a 4.5-fold regional disparity (Table 2). Each prefecture had a median of 2.0 (IQR 1.6–2.7) BCPs, ranging from 4.8 to 0.9 BCPs, respectively, resulting in a 5.3-fold regional disparity. Each prefecture had a median of 11.0 (IQR 9.2–12.7) BCCs, ranging from 17.9 to 6.4 BCCs, resulting in a 2.8-fold regional disparity (Table 2).

Table 2. Population-adjusted number of cardiac rehabilitation personnel per 100,000 population in each of 47 prefectures.

| Minimum | Median (IQR) | Maximum | Regional disparity Maximum/minimum |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation per 100,000 population | 1.9 | 3.4 (2.8–4.8) | 8.5 | 4.5 |

| Number of board- certified physiatrists per 100,000 population | 0.9 | 2.0 (1.6–2.7) | 4.8 | 5.3 |

| Number of board- certified cardiologists per 100,000 population | 6.4 | 11.0 (9.2–12.7) | 17.9 | 2.8 |

IQR: Interquartile range.

Figures 1 and 2 show the population-adjusted numbers of RICRs, BCPs, and BCCs and the numbers of inpatient and outpatient CR units, colored according to the regional distributions for each of the 47 prefectures.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the number of cardiac rehabilitation personnel per 100,000 population in 47 prefectures.

(a–c) Distributions of the numbers of registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation, board-certified physiatrists, and board-certified cardiologists, respectively, per 100,000 population in 47 prefectures. Pink to red colors: minimum to maximum. Middle value: median.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of the numbers of inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation units per 100,000 population in 47 prefectures.

(a, b) Distributions of the numbers of inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation units per 100,000 population in 47 prefectures, respectively. Pink to red colors: minimum to maximum. Middle value: median.

We observed significant correlations between the number of RICRs and inpatient CR units (r=0.647, P<0.001) and BCCs (r=0.439, P=0.002) (Figure 3). In contrast, a weak correlation was noted between inpatient CR units and the number of BCPs (r=0.329, P=0.024) (Figure 3). Moreover, our findings showed a significant correlation between the number of outpatient CR units and the numbers of RICRs (r=0.406, P=0.005) and BCCs (r=0.450, P=0.002) (Figure 4). However, we observed no correlation between the number of outpatient CR units and the number of BCPs (r=0.078, P=0.603) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Correlation between the number of inpatient cardiac rehabilitation units and the number of cardiac rehabilitation personnel.

(a–c) Correlations between the numbers of registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation, board-certified physiatrists, and board-certified cardiologists, respectively per 100,000 population and the number of inpatient rehabilitation units per 100,000 population.

Figure 4.

Correlation between the number of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation units and the number of cardiac rehabilitation personnel.

(a–c) Correlations between the number of registered instructors of cardiac rehabilitation, board-certified physiatrists, and board-certified cardiologists, respectively, per 100,000 population and the number of outpatient rehabilitation units per 100,000 population.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated large regional disparities in CR implementation among 47 prefectures in Japan, with 7- and 20.4-fold regional disparities in the number of CR units for inpatients and outpatients, respectively. Moreover, we also observed 4.5-, 5.3-, and 2.8-fold regional disparities in the numbers of RICRs, BCPs, and BCCs, respectively. Notably, the number of inpatient CR units was correlated with the number of RICRs and BCCs but weakly correlated with the number of BCPs. Finally, our results showed that the number of outpatient CR units was correlated with the number of RICRs and BCCs but not with the number of BCPs.

Previous studies have attributed the limited implementation of outpatient CR to the low number of facilities providing CR, poor facility locations, limited time available at the facilities, poor facility accessibility, and the cost of CR including out-of-pocket and transportation costs16). One study showed that 80.4% and 56.5% of patients with chronic heart failure underwent inpatient and outpatient CR, respectively17). Another study showed that 7.3% of patients with heart failure who received inpatient CR underwent outpatient CR after hospital discharge, suggesting low outpatient CR provision rates17). Consistent with these reports, the results of the current study showed that outpatient CR was performed less frequently than inpatient CR. The difficulty in shifting from inpatient to outpatient CR may be one explanation for the low number of outpatient CR units.

One study showed that attending physician recommendation was the most important factor affecting outpatient CR participation among older cardiac patients18). BCCs undergo training at facilities certified by the Japanese Circulation Society; these facilities have high implementation rates for inpatients (86.3%) and outpatients (60.4%) CR17). BCCs who were educated on CR during their training were more likely to recommend CR for outpatients with cardiac diseases, suggesting a stronger association between the numbers of outpatient CR units and BCCs.

A previous study showed that skilled healthcare providers play an important role in promoting heart failure care17). In recent years, outpatient CR has been critical in providing shorter hospitalizations and discharge of patients with heart disease who have received insufficient CR during their hospitalization. We believe that increasing the number of RICRs familiar with CR requires increasing the implementation of outpatient CR. Estimates have shown that the number of RICRs increases by approximately 500 to 600 annually13). An increased number of RICRs could reduce regional disparities in the number of outpatient CR units.

As the NDB database used in this study contains health insurance claims for over 90% of the entire Japanese population, information on almost all CR implementation units can be extracted, thereby reducing information bias.

However, the current study has several limitations. First, given the ecological study design, there are concerns regarding ecological fallacy. Moreover, the data for an entire prefecture may not always apply to an individual hospital. Second, the RICR system is unique to Japan, which limits the generalizability of our results to other countries. In other countries without similar systems, nurses18), exercise physiologists, and physical therapists19) perform this role, suggesting the need to investigate the involvement of CR-related professions in different countries. Third, we could not investigate other factors that could affect regional disparities, such as the residential environment and transportation methods. Fourth, our database did not include the diagnosis, severity, or treatment of cardiac diseases.

Conclusion

The results of the current study demonstrated large regional disparities in CR implementation. Our results also showed a correlation between the number of RICRs and rehabilitation units, suggesting that increasing the number of RICRs could promote increased CR provision in each region.

References

- 1.McMahon SR, Ades PA, Thompson PD. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2017; 27: 420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price KJ, Gordon BA, Bird SR, et al. A review of guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation exercise programmes: Is there an international consensus? Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016; 23: 1715–1733. doi: 10.1177/2047487316657669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turk-Adawi K, Sarrafzadegan N, Grace SL. Global availability of cardiac rehabilitation. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014; 11: 586–596. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patti A, Merlo L, Ambrosetti M, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs in heart failure patients. Heart Fail Clin 2021; 17: 263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2021.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto Y, Saito M, Iwasaka T, et al. Japanese Cardiac Rehabilitation Survey Investigators.Poor implementation of cardiac rehabilitation despite broad dissemination of coronary interventions for acute myocardial infarction in Japan: a nationwide survey. Circ J 2007; 71: 173–179. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grace SL, Gravely-Witte S, Brual J, et al. Contribution of patient and physician factors to cardiac rehabilitation enrollment: a prospective multilevel study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2008; 15: 548–556. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328305df05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park LG, Schopfer DW, Zhang N, et al. Participation in cardiac rehabilitation among patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 2017; 23: 427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison WN, Wardle SA. Factors affecting the uptake of cardiac rehabilitation services in a rural locality. Public Health 2005; 119: 1016–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doolan-Noble F, Broad J, Riddell T, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation services in New Zealand: access and utilisation. N Z Med J 2004; 117: U955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vonk T, Nuijten MAH, Maessen MFH, et al. Identifying reasons for nonattendance and noncompletion of cardiac rehabilitation: insights from Germany and the Netherlands. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2021; 41: 153–158. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.e-Stat General office for government statistics prefectures, gender and gender ratio-total population, Japanese population. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/file-download?statInfId=000031690317&fileKind=0; 2017. (Accessed Jan. 8, 2021)

- 12.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. National database of health insurance claims and specific health checkups of Japan, NDB Open Data Japan 4th. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000177221_00003.html; 2017. (Accessed May 5, 2021)

- 13.The Japanese Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation. https://www.jacr.jp/web/jacrreha/ (Accessed May 5, 2021)

- 14.The Japanese Association of Rehabilitation Medicine. https://www.jarm.or.jp/english/about/activities.html (Accessed May 5, 2021)

- 15.The Japanese Circulation Society. http://j-circ.or.jp/english/index.html (Accessed May 5, 2021)

- 16.Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67: 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiya K, Yamamoto T, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, et al. Nationwide survey of multidisciplinary care and cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure in Japan—an analysis of the AMED-CHF study. Circ J 2019; 83: 1546–1552. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deturk WE, Scott LB. Physical therapists as providers of care: exercise prescriptions and resultant outcomes in cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation programs in new york state. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2008; 19: 35–43. doi: 10.1097/01823246-200819020-00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sérvio TC, Ghisi GLM, Silva LPD, et al. Availability and characteristics of cardiac rehabilitation programs in one Brazilian state: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Phys Ther 2018; 22: 400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]