Abstract

Background:

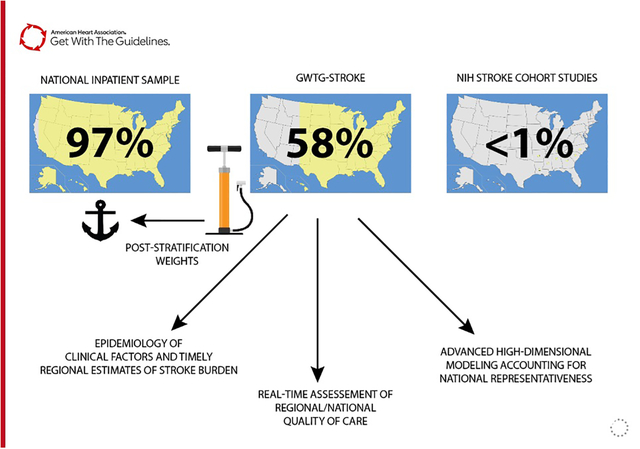

The U.S. lacks a timely and accurate nationwide surveillance system for acute ischemic stroke (AIS). We use the Get With The Guidelines® (GWTG) – Stroke registry to apply post-stratification survey weights to generate national assessment of AIS epidemiology, hospital care quality, and in-hospital outcomes.

Methods:

Clinical data from the GWTG-Stroke registry were weighted using a Bayesian interpolation method anchored to observations from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). To generate a U.S. stroke forecast for 2019, we linearized time trend estimates from the NIS to project anticipated AIS hospital volume, distribution, and race/ethnicity characteristics for the year 2019. Primary measures of AIS epidemiology and clinical care included patient and hospital characteristics, stroke severity, vital and laboratory measures, treatment interventions, performance measures, disposition, and clinical outcomes at discharge.

Results:

We estimate 552,476 patients with AIS were admitted in 2019 to US hospitals. Median age was 71 (IQR 60–81), 48.8% female. Atrial fibrillation was diagnosed in 22.6%, 30.2% had prior stroke/TIA, 36.4% had diabetes mellitus. At baseline 46.4% of AIS patients were taking antiplatelet agents, 19.2% anticoagulants, and 46.3% cholesterol-reducers. Mortality was 4.4% and only 52.3% were able to ambulate independently at discharge. Performance nationally on AIS achievement measures were generally higher than 95% for all measures but the use of thrombolytics within 3 hours of early stroke presentations (81.9%). Additional quality measures had lower rates of receipt: dysphagia screening (84.9%), early thrombolytics by 4.5 hours (79.7%), and statin therapy (80.6%)

Conclusions:

We provide timely, reliable, and actionable US national AIS surveillance using Bayesian interpolation post-stratification weights. These data may facilitate more targeted quality improvement efforts, resource allocation, and national policies to improve AIS care and outcomes.

Keywords: epidemiology, ischemic stroke, quality and outcomes, health services, Bayesian analysis, population surveillance

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Timely and accurate national surveillance of stroke and cardiovascular disease remains an immense challenge in the U.S. due to the lack of integration of various paper and electronic health record systems.1,2 Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) remains a leading cause of death and disability and may be prevented and treated with delivery of evidence-based AIS care.3–5 In 2018, 3.4% of Americans reported a history of stroke.6 Developing a national AIS surveillance system would allow for monitoring and responding to AIS burden, health equity, and quality of care.

The American Heart Association (AHA) sponsored The Get With The Guidelines® (GWTG) registry program includes reliable abstracted AIS clinical data for quality improvement and research analyses.7 Registry data is a convenience sample and not directly representative of a specific population of interest.8,9 Non-representative samples may be transformed into a representative ones using statistical methods such as post-stratification weights that rebalance over and under-represented segments of the target population of interest.10,11 A few community cohort and case-control studies are currently featured in the annual AHA statistical update on heart disease and stroke statistics, but are not nationally representative and inadequate to measure AIS burden and quality of care nationally.12–14 For this study, we use Bayesian interpolation to estimate post-stratification survey weights for the GWTG-Stroke registry to quantify the 2019 AIS burden, hospital quality of care, and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Data Source

Because of the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, requests to access the dataset from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the Get With The Guidelines - Stroke program to QualityResearch@heart.org. We used the GWTG-Stroke registry data from 2019 to model AIS epidemiology, clinical characteristics, hospital quality of care, and outcomes at discharge. 2019 was the most recent year not impacted by COVID-19 and the disruption of hospital services. GWTG-Stroke uses trained personnel to abstract reliable demographic, clinical, and event information from participating hospitals using an internet-based patient management tool.7 Identification of AIS is accurately identified and clinical variables such as admission and discharge stroke severity are systematically included, alongside detailed clinical data not available in administrative claims data alone. GWTG-Stroke includes 1,300–1,500 hospitals per year (out of approximately 5,300 U.S. community or federal hospitals nationally) and details are previously described.15–17 Hospitals participating in the GWTG program do so on a voluntary basis. Although the GWTG program contains many small, rural and non-academic hospitals, these hospital types are under-represented compared to the overall U.S. hospitalized population.8,11 Therefore, the sampling strategy does not directly estimate national AIS clinical characteristics as currently structured.

To determine the total number of AIS hospitalizations for 2019 in the U.S., marginal counts stratified by population characteristics are used to anchor post-stratification weights for GWTG-stroke. These estimates were derived from 2012 to 2018 from National Inpatient Sample (NIS) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. NIS is a structured random sample of U.S. hospitalizations that is then weighted to represent national hospital utilization. There are 4,550 community hospitals included in the NIS.18 However, the database does not include detailed clinical data such as stroke severity, laboratory data, medical treatments received, and patient reported outcomes. NIS samples 20% of the administrative discharge records from all participating hospitals (approximately 4,300 hospitals) covering 95% of the U.S. population and 94% of all community hospital discharges.19 While the NIS may be used estimate the total number of AIS hospitalization, basic demographics, procedure performed, and hospitalization costs, the database lacks detailed clinical and outcomes data important for AIS quality of care and outcomes assessment.

Data Definitions

In the NIS, AIS is defined using the primary discharge diagnosis from the first listed International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code or the beta Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) code “CIR020” (online supplement, Table S1 and S2).20,21 AIS is defined in GWTG-Stroke based on abstracted discharge diagnoses. GWTG-Stroke uses electronic case report form-based data extraction from clinical chart review to document patient-specific comorbid conditions, care quality, and clinical outcomes. Performance and quality metric definitions are provided (online supplement, Table S3 and S4). Only records with complete variables of interest were included, no imputation was performed.

Statistical Analysis

Annual AIS population counts stratified by patient (age group, sex, and race/ethnicity) and hospital factors (size, rurality, ownership, teaching status) were obtained between 2012 and 2018. Annual stratified population counts were linearized, and predictions made for the 2019 AIS population in the U.S. The derived 2019 NIS population counts were used to generate post-stratification weights for 2019 GWTG-Stroke observations using Bayesian population interpolation method previously validated.22 GWTG-Stroke observations (Bayesian prior) are fit to the marginal distributions of the 2019 NIS anchoring counts to estimate post-stratification weights for each hospitalization. Weighted GWTG-Stroke data is used to estimate national AIS clinical characteristics, laboratory values, and quality metrics. Findings followed the STROBE cohort study reporting guideline.23 Anchoring population counts from the NIS were analyzed in Stata 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA). All Bayesian analyses are performed in R 3.6.1 (R Foundation, Vienna Austria). Each participating hospital received either human research approval to enroll patients without individual consent under the Common Rule or a waiver of authorization and exemption from subsequent review by their institutional review board. IQVIA, Inc. serves as the data collection and coordination center. Duke Clinical Research Institute serves as the data analysis center and has an agreement to analyze the aggregate de-identified data for research purposes. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Duke University.

Results

In 2019, there were an estimated 552,476 AIS hospitalizations in the U.S. with a median age of 71 years (IQR, 60–81), 48.8% (95% CI, 48.5–49.2%) female, and 63.1% (95% CI, 62.7–63.5%) white (Table 1). With respect to comorbid conditions, 22.6% (95% CI, 22.3–22.8%) had an atrial fibrillation history or new diagnosis, prior stroke 30.2% (95% CI, 29.8–30.5%), diabetes mellitus 36.4% (95% CI, 36.1–36.8%), hypertension 76.5% (95% CI, 76.2–76.8%), and smoking 19.3% (95% CI, 19.1–19.6%). Only 46.4% (46.1–46.8%) of patients were taking antiplatelets at baseline, 19.2% (95% CI, 18.9–19.6%) anticoagulants, 46.3% (95% CI, 45.9–46.6%) on cholesterol reducing medications, and 29.0% (95% CI, 28.7–29.4%) on diabetic medications. 74.9% (95% CI, 74.4–75.3%) were treated in private, non-profit hospitals. The distribution of stroke severity using the NIH Stroke Scale/Score (NIHSS) was 58.7% (95% CI 58.3–59.0%) for the 0–4 category, 19.1% (95% CI 18.9–19.4%) for 5–9, 8.3% (95% CI 8.1–8.5%) for 10–14, 7.0% (95% CI 6.8–7.2%) for 15–20, and 6.9%, 95% CI 6.8–7.1%) for NIHSS greater than 20.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in ischemic stroke patients: the 2019 GWTG-Stroke sample and the entire U.S. based on the Bayesian weighted sample.

| Variable | GWTG-Stroke | U.S. 2019 (Bayesian Weighted) |

|---|---|---|

| N=414,628 | N=552,476 N (Proportion, 95% CI) |

|

| Patient Demographics | ||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 71 (61 – 81) | 71 (60 – 81) |

| Female | 203,249 (49.0%) | 269,840 (48.8%, 95% CI 48.5–49.2%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 278,602 (67.2%) | 348,457 (63.1%, 95% CI 62.7–63.5%) |

| Black | 74,227 (17.9%) | 92,875 (16.8%, 95% CI 16.5–17.1%) |

| Hispanic | 31,109 (7.5%) | 51,788 (9.4%, 95% CI 9.0–9.7%) |

| Asian & Pacific Islander | 13,871 (3.4%) | 24,302 (4.4%, 95% CI 4.2–4.6%) |

| Other | 16,819 (4.1%) | 35,053 (6.3%, 95% CI 6.1–6.6%) |

| Insurance | ||

| Private/VA/Champus/Other Insurance | 76,349 (22.5%) | 104,231 (23.0%, 95% CI 22.7–23.3% |

| Medicaid | 28,448 (8.4%) | 37,277 (8.2%, 95% CI 8.0–8.5%) |

| Medicare | 218,893 (64.4%) | 286,934 (63.3%, 95% CI 62.9–63.7%) |

| Self Pay/No Insurance | 15,983 (4.7%) | 25,120 (5.5%, 95% CI 5.3–5.8%) |

| Medical History | ||

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter history/new diagnosis | 95,507 (23.1%) | 124,192 (22.6%, 95% CI 22.3–22.8%) |

| Previous Stroke/TIA | 125,649 (30.5%) | 165,355 (30.2%, 95% CI 29.8–30.5%) |

| CAD/Prior Myocardial Infarction | 92,743 (22.5%) | 121,403 (22.1%, 95% CI 22.9–22.4%) |

| Carotid Stenosis | 14,934 (3.6%) | 19,187 (3.5%, 95% CI 3.4–3.6%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 147,794 (35.9%) | 199,675 (36.4%, 95% CI 36.1–36.8%) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 16,784 (4.1%) | 22,390 (4.1%, 95% CI 4.0–4.2%) |

| Hypertension | 315,574 (76.7%) | 419,251 (76.5%, 95% CI 76.2–76.8%) |

| Smoker | 77,756 (18.9%) | 105,826 (19.3%, 95% CI 19.1–19.6%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 200,575 (48.7%) | 262,999 (48.0%, 95% CI 47.6–48.3%) |

| Heart Failure | 41,726 (10.1%) | 54,609 (10.0%, 95% CI 9.8–10.2%) |

| Obesity/Overweight | 123,112 (29.9%) | 163,125 (29.8%, 95% CI 29.4–30.1%) |

| Chronic Renal Insufficiency | 43,135 (10.5%) | 56,779 (10.4%, 95% CI 10.2–10.6%) |

| Medications Prior to Admission | ||

| Antiplatelets | 177,052 (47.6%) | 230,322 (46.4%, 95% CI 46.1–46.8%) |

| Anticoagulants | 51,139 (20.0%) | 66,364 (19.2%, 95% CI 18.9–19.6%) |

| Antihypertensives | 227,286 (66.6%) | 304,648 (66.2%, 95% CI 65.8–66.6%) |

| Cholesterol-Reducers | 194,326 (47.2%) | 253,731 (46.3%, 95% CI 45.9–46.6%) |

| Diabetic Medications | 96,998 (28.8%) | 131,446 (29.0%, 95% CI 28.7–29.4%) |

| Stroke Presentation Severity | ||

| NIHSS Score categories | ||

| 0–4 | 226,953 (58.6%) | 299,827 (58.7%, 95% CI 58.3–59.0%) |

| 5–9 | 74,321 (19.2%) | 97,680 (19.1%, 95% CI 18.9–19.4%) |

| 10–14 | 32,530 (8.4%) | 42,466 (8.3%, 95% CI 8.1–8.5%) |

| 15–20 | 26,827 (6.9%) | 35,634 (7.0%, 95% CI 6.8–7.2%) |

| >20 | 26,884 (6.9%) | 35,406 (6.9%, 95% CI 6.8–7.1%) |

| Initial NIHSS Score (0–42), median (IQR) | 3 (1 – 8) | 3 (1 – 8) |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||

| Census Divisions | ||

| Division 1 New England | 17,640 (4.3%) | 23,847 (4.3%, 95% CI 4.2–4.5%) |

| Division 2 Mid-Atlantic | 63,949 (15.4%) | 71,472 (12.9%, 95% CI 12.7–13.1%) |

| Division 3 East North Central | 58,373 (14.1%) | 82,502 (14.9%, 95% CI 14.7–15.2%) |

| Division 4 West North Central | 28,034 (6.8%) | 35,975 (6.5%, 95% CI 6.3–6.7%) |

| Division 5 South Atlantic | 97,670 (23.6%) | 124,143 (22.5%, 95% CI 22.2–22.8%) |

| Division 6 East South Central | 27,333 (6.6%) | 44,053 (8.0%, 95% CI 7.7–8.2%) |

| Division 7 West South Central | 43,504 (10.5%) | 68,336 (12.4%, 95% CI 12.1–12.6%) |

| Division 8 Mountain | 21,446 (5.2%) | 30,018 (5.4%, 95% CI 5.3–5.6%) |

| Division 9 Pacific | 56,679 (13.7%) | 72,132 (13.1%, 95% CI 12.8–13.3%) |

| Hospital ownership | ||

| Government | 47,351 (11.4%) | 61,607 (11.2%, 95% CI 10.8–11.5%) |

| Private, Nonprofit | 319,389 (77.0%) | 413,545 (74.9%, 95% CI 74.4–75.3%) |

| Private, Investment | 47,888 (11.6%) | 77,324 (14.0%, 95% CI 13.7–14.3%) |

| Rural/teaching status | ||

| Rural | 19,371 (4.7%) | 32,793 (5.9%, 95% CI 5.5–6.3%) |

| Urban non-teaching | 89,200 (21.5%) | 90,735 (16.4%, 95% CI 16.1–16.8%) |

| Urban teaching | 306,057 (73.8%) | 428,948 (77.6%, 95% CI 77.2–78.1%) |

| Bed Size Categories* | ||

| Small | 53,558 (12.9%) | 96,760 (17.5%, 95% CI 17.1–17.9%) |

| Medium | 112,109 (27.0%) | 167,345 (30.3%, 95% CI 30.0–30.6%) |

| Large | 248,961 (60.0%) | 288,372 (52.2%, 95% CI 51.8–52.6%) |

| GWTG Hospital Characteristics | ||

| Primary Stroke Center | 302,198 (72.9%) | 397,705 (72.0%, 95% CI 71.6–72.4%) |

| Comprehensive Stroke Center | 97,461 (23.5%) | 126,893 (23.0%, 95% CI 22.8–23.2%) |

| Academic Hospital | 312,615 (75.4%) | 436,212 (79.0%, 95% CI 78.5–79.4%) |

defined by Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project definitions

TIA= Transient Ischemic Attack, CAD = Coronary Artery Disease, NIHSS = NIH Stroke Scale/Score

In terms of outcomes, the median hospital stay was 4 days (IQR, 2–6 days) (Table 2). Disposition at discharge included 275,033 (49.8%, 95% CI 49.4–50.1%) to home, 208,289 (37.7%, 95% CI 37.4–38.0%) to another health care facility primarily for skilled nursing or inpatient rehabilitation, 21,908 (4.0%, 95% CI 3.8–4.1%) died, and 16,987 (3.1%, 95% CI 3.0–3.2%) were discharged to hospice facilities. Among patients with documented ambulatory status, 62,652 (12.5%, 95% CI 12.3–12.8%) were unable to ambulate and 154,188 (30.8%, 95% CI 30.5–31.2%) need assistance with ambulation.

Table 2.

Short term outcomes and stroke performance metrics in ischemic stroke patients: the 2019 GWTG-Stroke sample and the entire U.S. based on the Bayesian weighted sample.

| Variable | GWTG-Stroke | U.S. 2019 (Bayesian Weighted) |

|---|---|---|

| N=414,628 | N=552,476 N (Proportion, 95% CI) |

|

| Short term outcomes | ||

| Length of stay, days, median (IQR) | 4 (2 – 6) | 4 (2 – 6) |

| Discharge Disposition | ||

| Home | 204,586 (49.3%) | 275,033 (49.8%, 95% CI 49.4–50.1%) |

| Home Hospice | 6,568 (1.6%) | 8,526 (1.5%, 95% CI 1.4–1.7%) |

| Hospice Facility | 12,727 (3.1%) | 16,987 (3.1%, 95% CI 3.0–3.2%) |

| Acute Care Facility | 9,758 (2.4%) | 15,009 (2.7%, 95% CI 2.5–2.9%) |

| Other Health Care Facility | 159,492 (38.5%) | 208,289 (37.7%, 95% CI 37.4–38.0%) |

| Expired | 16,530 (4.0%) | 21,908 (4.0%, 95% CI 3.8–4.1%) |

| Left Against Medical Advice | 4,292 (1.0%) | 5,650 (1.0%, 95% CI 1.0–1.1%) |

| If “Other Health Care Facility” | ||

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 70,714 (44.4%) | 91,998 (44.3%, 95% CI 43.7–44.8%) |

| Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility | 82,889 (52.1%) | 107,735 (51.9%, 95% CI 51.3–52.4%) |

| Long Term Care Hospital | 3,274 (2.1%) | 4,624 (2.2%, 95% CI 2.1–2.4%) |

| Intermediate Care facility | 952 (0.6%) | 1,370 (0.7%, 95% CI 0.6–0.8%) |

| Other | 1,316 (0.8%) | 2,067 (1.0%, 95% CI 0.9–1.1%) |

| Thrombolytic Complications – Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage <36 hours | 3,316 (3.8%) | 4,263 (3.7%, 95% CI 3.6–3.9%) |

| Discharge ambulatory status | ||

| Unable to ambulate | 46,481 (12.3%) | 62,652 (12.5%, 95% CI 12.3–12.8%) |

| With assistance from person | 118,271 (31.2%) | 154,188 (30.8%, 95% CI 30.5–31.2%) |

| Able to ambulate independently | 197,933 (52.2%) | 261,561 (52.3%, 95% CI 51.9–52.7%) |

| Modified Rankin Scale at Discharge Total, median (IQR) | 3 (1 – 4) | 3 (1 – 4) |

| Achievement Measures | ||

| Acute - IV Thrombolytics Arrive by 2 Hours, Treat by 3 Hours | 30,584 (83.8%) | 38,980 (81.9%, 95% CI 80.7–83.1%) |

| Acute - Early Antithrombotics | 238,022 (97.0%) | 315,212 (96.9%, 95% CI 96.7–97.0%) |

| Acute - VTE Prophylaxis | 302,435 (99.2%) | 398,744 (99.2%, 95% CI 99.1–99.3%) |

| At or by discharge - Antithrombotics | 340,563 (99.2%) | 450,912 (98.9%, 95% CI 98.7–99.0%) |

| At or by discharge - Anticoagulation for Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter | 55,552 (97.2%) | 71,710 (96.9%, 95% CI 96.5–97.4%) |

| At or by discharge - Smoking Cessation | 65,657 (97.9%) | 88,352 (97.2%, 95% CI 96.6–97.8%) |

| At or by discharge - Statin Prescribed at Discharge | 250,031 (98.9%) | 328,842 (98.7%, 95% CI 98.7–98.9%) |

| GWTG/PAA Defect-free Measure | 363,743 (94.3%) | 480,112 (93.7%, 95% CI 93.4–93.9%) |

| Quality Measures | ||

| Acute - Dysphagia Screen | 316,185 (85.8%) | 415,863 (84.9%, 95% CI 84.5–85.2%) |

| Acute - Time to Intravenous Thrombolytic Therapy – 60 minutes | 30,131 (86.3%) | 38,045 (85.0%, 95% CI 83.8–86.1%) |

| Acute - IV Thrombolytics Arrive by 3.5 Hours, Treat by 4.5 Hours | 40,715 (81.3%) | 52,199 (79.7%, 95% CI 78.8–80.7%) |

| Acute - NIHSS Reported | 353,181 (93.8%) | 466,975 (92.9%, 95% CI 92.5–93.2%) |

| At or by discharge - Stroke Education | 192,279 (95.8%) | 256,626 (95.2%, 95% CI 94.8–95.5%) |

| At or by discharge - Rehabilitation Considered | 347,797 (99.0%) | 460,709 (98.8%, 95% CI 98.7–98.9%) |

| At or by discharge - LDL Documented | 325,527 (93.5%) | 429,722 (93.1%, 95% CI 92.8–93.3%) |

| At or by discharge - Intensive Statin Therapy | 130,069 (81.2%) | 173,858 (80.6%, 95% CI 80.1–81.0%) |

| Additional Metrics | ||

| Door to CT time, min, median (IQR) | 33 (13 – 87) | 32 (13 – 86) |

| IV Thrombolytic use | 47,292 (11.4%) | 60,510 (11.0%, 95% CI 10.8–11.1%) |

| Door to IV thrombolytic time, min, median (IQR) | 49 (35 – 68) | 49 (35 – 69) |

| Endovascular treatment use | 29,939 (7.2%) | 39,008 (7.1%, 95% CI 6.9–7.2%) |

| Door to endovascular treatment time, min, median (IQR) | 87 (53 – 128) | 86 (53 – 127) |

VTE = venous thromboembolism, GWTG/PAA = Get With The Guideline / Performance Achievement Award, NIHSS = NIH Stroke Scale/Score

For early onset AIS presenting within 2 hours, 38,980 (81.9%, 95% CI, 80.7–83.1%) of eligible AIS patients received thrombolytics IV within 3 hours of presentation. Receipt of early antithrombotics, and venous thromboembolic prophylaxis were greater than 95%. Indicated therapies at discharge were provided at a high rate (>95%) for antithrombotics, anticoagulation for atrial flutter or fibrillation, smoking cessation recommendations, and statin therapy. Defect free care was received by 480,112 (93.7%, 95% CI 93.4–93.9%), defined has no deficiencies across all seven AIS performance measures. However, some quality measures had lower rates of receipt. Dysphagia screening occurred in 415,863 (84.9%, 95% CI 84.5–85.2%) of patients with AIS, time to thrombolysis within 60 minutes for eligible patients occurred for 38,045 (85.0%, 95% CI 83.8–86.1%) of indicated patients, and intensive statin therapy was only received for 173,858 (80.6%, 95% CI 80.1–81.0%) of patients.

Discussion

There remains an immense challenge in monitoring AIS epidemiology, clinical care, and outcomes using existing data structures. This study used a novel method to apply post-stratification weights to an existing large GWTG-Stroke registry to describe national stroke epidemiology, clinical care, and outcomes for the year 2019. NIS is typically released with a two to three lag and consists of administrative data, while GWTG data are verified by chart review by train personnel with accuracy checks and the data are mostly complete and analyzable within 6 months. We used the NIS to select reliable anchoring variables to generate post-stratification survey weights for the GWTG-Stroke registry. We believe our approach provides accurate and near real-time estimates of AIS burden and clinical outcomes.

Currently, the American Heart Association stroke prevalence estimates are based on self-report from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) which is a limited sample of community participants with a risk of health selection bias.6,24 Smaller cohort studies sponsored from the National Institutes of Health are featured for characterizing stroke incidence and etiology with non-representative national populations.14,25 The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) estimates 795,000 incident new or recurrent strokes per year using these cohorts and unpublished methods.26 Our study improves the reliability of these estimates by applying Bayesian interpolation to a large stroke patient registry anchored to nationally representative hospital claims data to characterize the U.S. AIS population.

Nationally we observe a large AIS burden suggesting large gaps in care prehospitalization that would likely reduce the risk of both primary and secondary AIS events. Less than half of patients presenting with AIS receive antiplatelet or cholesterol reducing medications prior to hospital presentation. Overall, patients seen in participating GWTG-Stroke hospitals receive excellent and timely care but areas for quality improvement remain. The early recognition, treatment, and appropriate screening during hospitalization remain critical areas for care improvement.

Clinical outcomes remain severe at discharge with large proportions of patients post-AIS events requiring rehabilitation or extended inpatient care. This highlights the importance of population health to prevent both primary and secondary stroke attack rates. Strategies that encourage population-wide hypertension control, atherosclerotic risk reduction with use of cholesterol lowering therapies, anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation/flutter, and antiplatelet agents for indicated patients will reduce the incidence of AIS.

In terms of limitations, this study’s methods may not accurately forecast large shifts in cardiovascular disease related to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. We applied these methods to 2019 data to avoid issues related to delayed AIS presentation and shifts in cardiovascular health related to the COVID-19 pandemic and large behavioral changes. GWTG-Stroke includes over 1,500 hospitals that primarily provide stroke services and voluntarily participate in the GWTG-Stroke quality improvement program. Participating hospitals may provide higher quality care relative to hospitals not participating in the GWTG-Stroke program.27,28 Non-participating hospitals likely treat a smaller portion of AIS patients. Nevertheless, our estimates for care quality might be on the higher end of true national performance. The Bayesian interpolation method is not able to adjust for unknown confounders. However, we believe that by balancing hospital characteristics related to size and rurality we closely approximate national AIS care quality of care.

Conclusion

This study provides an overview of the burden of AIS and delivers more timely representative reports of the national population health. The post-stratification Bayesian survey weights and forecasting approach allows for more timely evaluation of trends in AIS hospital presentations and quality of care assessments. By leveraging clinically valuable data from a high-quality national stroke registry program to make national estimates, we provide a broad overview of epidemiologic clinical and hospital factors underlying the stroke epidemic that can be sustained for the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Sources of Funding:

B. Ziaeian and this research are supported by the AHA 17SDG33630113. B. Ziaeian is also supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number KL2TR001882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The Get With The Guidelines®–Stroke (GWTG-Stroke) program is provided by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. GWTG-Stroke is sponsored, in part, by Novartis, Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Tylenol and Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. IQVIA (Parsippany, New Jersey) serves as the data collection and coordination center. Duke Clinical Research Institute (Durham, NC) serves as the data analysis center

Disclosures:

Boback Ziaeian: none

Haolin Xu: none

Eric E. Smith: none

Ying Xian: research grant from the National Institute On Aging (R01AG062770 and R01AG066672), and Genentech.

Lee H Schwamm: Consultant: Boehringer Ingelheim; Research grants: NINDS, NIA, PCORI; Serves on scientific advisory boards for (1) LifeImage (2) Medtronic clinical trial design for AF related stroke NCT02700945 (3) Penumbra MIND study DSMB NCT03342664, (4) Genentech TIMELESS study NCT03785678 Steering Committee, and expert advisory panel on late window thrombolysis, (5) Diffusion Pharma DSMB PHAST-TSC NCT03763929. Serves as volunteer chair of the AHA/ASA stroke systems of care advisory committee, and ASA Advisory Committee of the AHA Board of Directors [unpaid]

Yosef Khan: Premier Inc.

Roland A. Matsouaka: none

Gregg C. Fonarow: Research: American Heart Association, NIH; Consulting: Abbott, Amgen, Bayer, Janssen, Medtronic, and Novartis

Abbreviations

- AHA

American Heart Association

- AIS

Acute Ischemic Stroke

- GWTG

Get With The Guidelines®

- NIS

National Inpatient Sample

Footnotes

References

- 1.Committee on a National Surveillance System for Cardiovascular and Select Chronic Diseases; Institute of Medicine, IOM (Institute of Medicine). A Nationwide Framework for Surveillance of Cardiovascular and Chronic Lung Diseases [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/13145 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidney S, Rosamond WD, Howard VJ, Luepker RV. The “Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2013 Update” and the Need for a National Cardiovascular Surveillance System. Circulation. 2013;127:21–23. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23239838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2019.

- 4.Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, Cockroft KM, Gutierrez J, Lombardi-Hill D, Kamel H, Kernan WN, Kittner SJ, Leira EC, et al. 2021 Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack; A guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. 2018.

- 6.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Cheng S, Delling FN, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2021 Update. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–e743. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xian Y, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Webb LE, Blevins J, Demyanenko VS, Zhao X, Olson DM, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, et al. Data quality in the American Heart Association Get with the Guidelines-Stroke (GWTG-Stroke): Results from a National Data Validation Audit. Am. Heart J 2012;163:392–398.e1. Available from: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves MJ, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Pan W, Olson D, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Schwamm LH. Representativeness of the get with the guidelines-stroke registry: Comparison of patient and hospital characteristics among medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heidenreich PA, Fonarow GC. Are registry hospitals different? A comparison of patients admitted to hospitals of a commercial heart failure registry with those from national and community cohorts. Am. Heart J 2006;152:935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt D, Smith TMF. Post Stratification. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1979;142:33. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/2344652?origin=crossref [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziaeian B, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, Xian Y, Khan Y, Schwamm LS, Smith EE, Fonarow GC. National surveillance of stroke quality of care and outcomes by applying post-stratification survey weights on the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke patient registry. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 2021;21:23. Available from: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-021-01214-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS, Howard G. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–43. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/86678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broderick J, Brott T, Kothari R, Miller R, Khoury J, Pancioli A, Gebel J, Mills D, Minneci L, Shukla R. The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study: Preliminary first-ever and total incidence rates of stroke among blacks. Stroke. 1998;29:415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Hospital Association. Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2022 [Internet]. Chicago, Illinois: 2022. Available from: https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaBresh KA, Reeves MJ, Frankel MR, Albright D, Schwamm LH. Hospital treatment of patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack using the “Get With The Guidelines” program. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:411–417. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18299497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Pan W, Frankel MR, Smith EE, Ellrodt G, Cannon CP, Liang L, Peterson E, et al. Get With the Guidelines-Stroke is associated with sustained improvement in care for patients hospitalized with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation. 2009;119:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2019 [Internet]. Rockville, MD: 2021. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2013 [Internet]. Rockville, Maryland: 2015. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang TE, Lichtman JH, Goldstein LB, George MG. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM Codes by Hospital Characteristics and Stroke Severity: Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Program. J. Am. Heart Assoc 2016;5:1–7. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.115.003056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classificiations Software (CCS) for ICD-10-PCS [Internet]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp#overview

- 22.Ziaeian B, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, Xian Y, Khan Y, Schwamm LS, Smith EE, Fonarow GC. National surveillance of stroke quality of care and outcomes by applying post-stratification survey weights on the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke patient registry. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 2021;21:23. Available from: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-021-01214-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med 2007;147:W. Available from: http://annals.org/article.aspx?doi=10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fakhouri THI, Martin CB, Chen T-C, Akinbami LJ, Ogden CL, Paulose-Ram R, Riddles MK, Van de Kerckhove W, Roth SB, Clark J, et al. An Investigation of Nonresponse Bias and Survey Location Variability in the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Vital Health Stat 2. 2020;1–36. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33541513 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS, Howard G. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: Objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, Boehme AK, Buxton AE, Carson AP, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Song S, Fonarow GC, Olson DM, Liang L, Schulte PJ, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Reeves MJ, Smith EE, Schwamm LH, et al. Association of get with the guidelines-stroke program participation and clinical outcomes for medicare beneficiaries with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:1294–302. Available from: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/early/2016/04/13/STROKEAHA.115.011874.abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard G, Schwamm LH, Donnelly JP, Howard VJ, Jasne A, Smith EE, Rhodes JD, Kissela BM, Fonarow GC, Kleindorfer DO, et al. Participation in Get with the Guidelines-Stroke and Its Association with Quality of Care for Stroke. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1331–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.