1. Background

The worldwide outbreak of SARS-COV2 has fueled a renewed interest in virtual delivery of healthcare services. Historically, telehealth has facilitated delivery of healthcare to patients living in remote areas with limited access to medical professionals. As the video camera and television became commonplace in the 1950s, medicine began to leverage these new technologies [1]. The unprecedented strain that SARS-COV2 has placed upon the healthcare system, and society at large, has created a “perfect storm” from which telehealth has emerged as a potential solution that allows us to continue to social distance while maintaining our current state of healthcare delivery. Practice venues ranging from Primary Care to the Emergency Department have started to trial mechanisms to treat non-emergent patients virtually [2].

The literature contains many examples of successful trials of “virtual” evaluation and treatment for musculoskeletal disorders [[3], [4], [5], [6]]. Truter et al. showed this in their low back feasibility trial while Russell et al. and Richardson et al. achieved similar success and results when researching disorders of the lower limb and knee. All three studies demonstrated the effectiveness and acceptability of a remote evaluation [5,7,8]. Some advocates feel the widespread implementation of telemedicine has the potential to minimize Emergency Department (ED) or Urgent Care Clinic traffic, creating more efficient workflows in those settings [9]. Others have demonstrated that the cost of a visit is reduced significantly in time and travel [10]. However, despite this interest in the potential benefits of telemedicine, there are still questions about safety and efficacy, as well as the level of satisfaction by patients and acceptance by providers. There has been significant research and adoption of telehealth solutions in the fields of neurology and rheumatology, but telehealth use for LBP, and musculoskeletal conditions in general, has lagged behind [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. Telehealth solutions to treat and intervene in LBP are in their infancy. There is no formal established research agenda proposed by the NIH or other funding agencies and the treatment environment is fraught with practitioners brewing up “treatment du jour”.

The objective of this systematic review was to address the following questions:

-

•

What is the effectiveness and safety of “synchronous” tele-rehab visits in the treatment of patients with acute or chronic low back pain?

-

•

What is the level of satisfaction in patients who use tele-rehab vs. those who use in person consults for acute or chronic low back pain?

-

•

What is the level of provider satisfaction with patients who use tele-rehab vs. those who use in person consults for acute or chronic low back pain?

Additionally, we will propose a potential model for a research agenda. In the past research has depended on the knowledge translation model to bring findings form the “bench to the bedside.” The results have been mixed with inconsistent uptake of new research and difficulties with clinical application. The emergence of implementation science has provided a formal structure for applying and integrating research evidence into practice and could serve as a foundation for future research [18].

2. Methods

A protocol for this systematic review was registered a priori through PROSPERO (CRD42020212006). Protocol development and execution was completed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) [19]. Our search strategy can be found in Appendix A . Selection strategy, eligibility and details of our analytic process can be found below.

2.1. Search strategy

Our search strategy attempted to identify literature, specifically randomized clinical trials, that includes a synchronous tele-rehab evaluation or intervention for the treatment of acute low back pain. For the purposes of this study, the intervention must include a live, “real time” video interaction between the patient and the provider. The platform through which the interaction occurs may vary if there is a real time interaction with the provider.

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) protocol, an exhaustive search of the existing literature was performed by a research librarian (RT). Sources queried included the following databases: Ovid Medline, Embase, Ebsco CINHAL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Trials, Cochrane Protocols, PEDro, ClinicalTrials.gov and the Index of Chiropractic Literature. We expanded our formal inquiry to include an extensive search of the grey literature to include ongoing/registered clinical trials, protocols conference proceedings and abstracts. Finally, we performed a hand search of identified systematic reviews and meta analyses to identify additional articles that were missed in the initial database search. All databases were searched from inception to September 2020. Search strategies and keywords used for each database can be found in Appendix A.

2.2. Study eligibility

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria for scientific articles were identified a priori. Studies were included if they were a clinical trial or cohort study (prospective or retrospective), published or available in the English language, included subjects over the age of 18 years seeking care for an acute or chronic episode of low back pain and examined synchronous telehealth for evaluation or treatment. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were identified and used to confirm our search strategy, and to identify individual studies that may have been missed. However, they were not rated for quality or included in our final analysis.

2.3. Research team and study selection

Our research team consisted of 3 physical therapists (AP, MeS, CB) 2 chiropractors (ZC, MJS) 1 research assistant (SD) and a dual licensed physical therapist/chiropractor (SM). All had previous training and experience with systematic reviews. Titles and abstracts for each reference were screened independently by 2 of the above team members using Distiller SR, a web based systematic review and literature manager [20]. Disagreements during title and abstract screening were discussed between reviewers and adjudicated by the principal investigator (CB). Disagreements that could not be resolved mandated a full text review of the article in question. Full text evaluation was completed using 2 independent investigators, with disagreements being mediated by the principal investigator (CB). Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria after full text review were removed from consideration.

2.4. Assessment of study quality and data extraction

The following information was extracted from included articles: title, author, study design, participant inclusion/exclusion criteria, participant demographic and clinical characteristics, intervention specifics, and outcomes. In addition to the risk of bias assessment, the demographic data extracted included title, author, study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, participants, intervention specifics, and outcomes. These can be found in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Non-randomized trials with synchronous interaction.

| Study | Sample Size | Population and Source | Study/Intervention | Outcomes | Results | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cottrell et al., 2019 | 15 Control 46 Telehealth | Participants were recruited from advanced-practice physiotherapy-led screening service in a single metropolitan hospital (Brisbane, Australia. All patients attending an initial visit with the service were approached to participate in this study. As per standard practice, patients were referred to the service under study having been triaged from neurosurgical or orthopedic outpatient services with a non-urgent musculoskeletal spinal condition | Non-Randomized non-inferiority clinical trial to compare usual non-surgical care for back or neck pain with telerehabilitation care for the same condition. Neck and back pain were combined for this study as was pragmatic service referral. | Primary outcome measures were the Oswestry disability index and the Neck Disability Index. Secondary measures included self-reported pain and quality of life measures. | There were no significant group-by-time interactions observed for either pain-related disability (p ¼ 0.706), pain severity (p ¼ 0.187) or health-related quality of life (p ¼ 0.425) measures. The telerehabilitation group reported significantly higher levels of treatment satisfaction (median: 97 vs. 76.5; p ¼ 0.021); | 22/22 LOW RISK |

| Palacin-Marin et, al (2013) | N = 15 | Initially recruited 42 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of chronic LBP referred to a single rehabilitation center. 15 participants eventually enrolled. | Repeated measures crossover design for criterion validity and rater reliability | Lumbar Spine Mobility | Reliability between face-to-face and telerehabilitation evaluations was more than 0.80 for 7 of the 9 outcome measures. Very good inter- and intrarater intraclass correlation coefficients were obtained (0.92–0.96). | 22/24 LOW RISK |

| Back Muscle Endurance | ||||||

| Lumbar Motor Control | ||||||

| Disability Assessment | ||||||

| Pain Assessment | ||||||

| Health Related Quality of Life | ||||||

| Kinesiophobia | ||||||

| Peterson et al. (2019) | N = 47 | 47 participants with <90-day history of LBP recruited from two private practice outpatient orthopedic clinics | Repeated measures correlation design comparing face-to-face evaluation with synchronous telehealth evaluation using a modified treatment based classification algorithm | Patient Satisfaction | Rate of agreement was 68.1% (κ = 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.32–0.72). There was no difference in classification distributions between assessments (χ 2 = 2.14, p = 0.54). The percentage agreement was 48.9%–59.6% for classification variables. | 24/24 LOW RISK |

| HIPPA compliant Zoom | Rater agreement: | |||||

| Centralization or Peripheralization | ||||||

| Aberrant movements | ||||||

| SLR>91 | ||||||

| SLR>10 asymmetry | ||||||

| SLR large but <91 | ||||||

| Active straight leg raise | ||||||

| Truter et al. (2014) | N = 26 | 26 participants with current or recent LBP (2 years) recruited from small town in Queensland Australia. | Single blind validation study comparing face-to-face evaluation with synchronous telehealth evaluation | Disability | High levels of agreement found with detecting pain with lumbar movements, symptom reproduction and the SLR test. Moderate agreement occurred with identifying directional preference and active lumbar spine range of motion. Poor agreement with postural analysis. | 17/24 MODERATE RISK |

| eHAB conference system | Pain | |||||

| Posture | ||||||

| Active Movement | ||||||

| SLR Test | ||||||

| Satisfaction | ||||||

| Varkey et al. (2008) | N = 100 Only 8 (Seeking spine care) | 100 Consecutive patients from an onsite work clinic seeking primary care for an acute episode (84) or return visit (16) | Independently developed (Mayo Clinic) videoconference system, connected to medical records. | Pt. perceptions: | Overall, the authors concluded that patients and providers felt that telemedicine is feasible and, in some cases, preferred. A significant limitation to this study, however, was the small number of patients with LBP. | 7/16 HIGH RISK |

| Saved travel time | ||||||

| Saving appt. time | ||||||

| Prevent work absence | ||||||

| Saving other costs | ||||||

| Preventing work re-distribution. |

Study quality and risk of bias for randomized clinical trials was assessed using the Cochrane revised tool to assess risk of bias in randomized clinical trials (RoB2) [21]. This tool has been validated specifically for randomized clinical trials. Study quality and risk of bias for studies that involved face-to-face assessments but were not randomized clinical trials, will be assessed using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS). This validated tool was developed specifically to assess the methodological quality of comparative and non-comparative, non-randomized trials [22]. The tool consists of a total of 12 items; 8 items are relevant for all studies and 4 additional items are relevant for comparative studies. Each item is given one of 3 numeric ratings: “0 not reported”, 1 “reported but inadequate” or 2 “reported and adequate”. Risk of bias was assessed by 2 team members for each study (ZC and SM) with conflicts discussed and adjudicated by the PI (CB) [22].

3. Results

3.1. Study identification

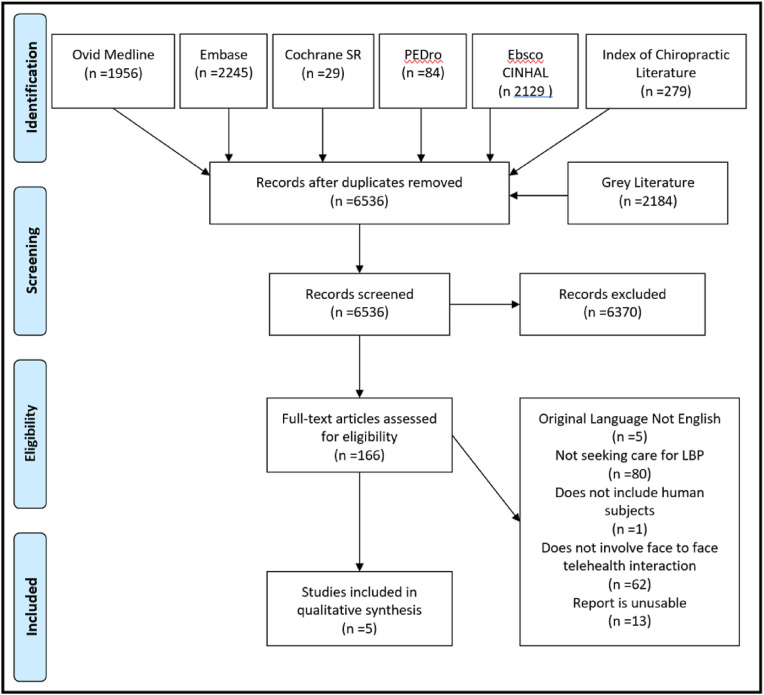

After our initial search, we removed 2261 duplicates and identified 6536 unique articles (Fig. 1 ). We then screened the title and abstract and excluded 6370 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. 166 articles underwent a full-text review. During this level of review, we excluded 5 articles because they were not in the English language; 80 articles because the participants were not seeking care for an episode of low back pain; 14 articles because the type of article was unusable; 1 article because it did not include human subjects; and 62 articles because they did not involve a synchronous telehealth interaction. Further review of the excluded articles revealed 15 clinical trials and 2 cohort studies that did not have a face-to-face clinical intervention but would have otherwise met our inclusion criteria. The research design and telehealth interventions studied in these 17 articles appeared to cluster around 3 themes: 1) Self-help exercise websites; 2) Online exercise smartphone applications; and 3) Telephonic telehealth interventions. The study outcomes included pain, disability, and satisfaction. Summaries of these 17 studies are provided in evidence tables and can be found in Appendix C and D.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Diagram.

We found 5 additional studies that met our inclusion criteria, but none were randomized controlled trials. The first article, Cottrell et al. [23] was a non-randomized cohort that used a non-inferiority approach. The authors attempted to establish that the use of a telerehabilitation approach (specifically videoconferencing) was non-inferior to in-person physiotherapy in treating patients with LBP or neck pain. Participants were recruited from an existing advanced-practice physiotherapy-led screening service. Patients with non-emergent spinal conditions were referred to this service after triage from neurosurgical or orthopedic outpatient services. Eligible patients chose whether they received treatment in-person (control group) or via telerehabilitation (intervention group). Outcome measures consisted of pain-related disability, pain severity, and health-related quality of life recorded at four separate time points (baseline, 3-, 6-, and 9-months). Disability and pain were assessed using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)and Neck Disability Index (NDI). Pain was assessed with a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS). Quality of life was assessed with the AQoL-6D. The telehealth intervention leveraged the eHAB telerehabilitation system (eHAB; NeoRehab, Brisbane, QLD, Australia). eHAB is a computer-based video conferencing system that works via a wireless 3G Internet connection. It provides real time video conferencing, advanced media tools including chat platforms, home exercise prescription software, remote measurement of joint and body position and real time video feedback between patients and clinicians. The authors found there were no significant group-by-time interactions for pain-related disability, pain severity, and health-related quality of life measures. These findings appear to indicate that in terms of the previously mentioned outcomes, that treatment via telerehabilitation was not inferior to in person treatment. A significant limitation of the study is that the authors collapsed subjects with neck and back pain into a single group. Despite this limitation the authors could not establish the superiority of any clinical outcome measure, thus demonstrating the equanimity between video and in person treatment for low back and neck pain [23].

The remaining 4 articles studied the reliability, validity, and feasibility of exam procedures. Each article used a standard in-person evaluation compared with a synchronous telerehabilitation evaluation. The next four paragraphs will provide summaries of each of these 4 studies, which are also listed in Table 1.

The first article by Palacin-Marin et al. [24] was a pilot, repeated-measures crossover study that assessed the agreement between a face-to-face evaluation and a telerehabilitation evaluation for patients seeking care for chronic low back pain. The study was conducted in a primary care environment. Assessments were completed by 2 physical therapists with more than 10 years of experience treating chronic low back pain. The telehealth evaluations used a web-based system with a real-time connection via Skype. Joint angles and movement were assessed using Kinovea (www.kinovea.org), an open-source video analysis package. Agreement between raters was assessed using Cronbach's α with agreement above 0.94 for all but lateral flexion and the Sorensen test. The authors concluded that their telerehabilitation system performed an adequate assessment for individuals with chronic back pain. Future research is warranted on larger samples [24].

Petersen et al. [25] performed a repeated-measures correlation design to assess the criterion validity and inter/intra rater reliability between a face-to-face evaluation and a synchronous telerehabilitation evaluation. The study, conducted in a physical therapy clinic, involved two physical therapists who completed all assessments. Telehealth assessments used a HIPPA compliant version of Zoom, two personal computers and an iPad. Examination procedures followed an assessment based on the Treatment Based Classification for Low Back Pain. (TBC) [[26], [27], [28]] Patient satisfaction with the telehealth assessment was also assessed. Agreement for specific variables of the TBC varied between 49% and 59%. Classification agreement hovered between 25% and 38% for both assessments. Regarding satisfaction, 56% of patients agreed or strongly agreed that the face-to-face assessment was as good as the telerehabilitation assessment, while 97% agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend the telerehabilitation assessment to someone unable to travel. The authors concluded that, based on patient satisfaction, the telerehabilitation system performed an adequate assessment. However, they recognized that the difficulties with the TBC evaluation might not be a function of the telehealth environment; rather, these disagreements are consistent with previously recognized disagreements with classification [25].

Truter et al. [7] completed a single-blind validation study comparing a face-to-face assessment with a synchronous telerehabilitation assessment. Two physical therapists were randomly assigned to complete the in-person evaluation of the telerehabilitation evaluation. The telehealth assessments used the eHAB telerehabilitation system (eHAB v2; NeoRehab, Brisbane, QLD, Australia). eHAB is a computer-based video conferencing system that works via a wireless 3G Internet connection. Physical assessments included posture, active movement, and the SLR. Psychometric assessments included disability (ODI), pain (VAS), and a satisfaction survey. Agreement with postural assessment varied widely from 25% agreement for the presence of a lumbar lordosis to 75% agreement for anterior/posterior positioning of the pelvis. Pearson's correlation for range of motion measurements correlated well for lumbar flexion (0.89) and extension (0.83). Lateral flexion showed moderate correlation of (0.69) on the right and (0.67) on the left. The agreement on the SLR test was 90% for pain and 84% for symptom reproduction. Symptom reproduction for SLR sensitization maneuvers was 90% for SLR with dorsiflexion, 86% for hip internal rotation, and 82% for active neck flexion. Patient satisfaction was similar to the Peterson study. The authors recognized that based on satisfaction, there is value in the telerehabilitation assessment but acknowledged limitations surrounding the agreement of postural assessments. These disagreements, however, may not be a function of the telerehabilitation evaluation. It is more likely that the disagreements are representative of the existing variations in postural assessment [7].

Varkey et al. [29] completed a feasibility study evaluating patient and provider satisfaction with a work site telemedicine clinic. The study evaluated 100 consecutive patients seen for a variety of primary care ailments including low back pain. Two physicians and 2 nurse practitioners completed telemedicine visits using an independently developed videoconference system, connected to radiology, pharmacy, and patient medical records. There is no information available about the components of the low back evaluations. Patient and provider perceptions were the primary outcomes. Patient perceptions included: opinions of saved travel time; saving time in appointment scheduling; preventing work absence; saving other costs; and preventing re-distribution of work to colleagues. Provider perceptions included: does a telehealth visit feel similar to a face-to-face visit; could they clearly hear the patient; and did telemedicine have a positive effect on their relationship with the patient. Overall, the authors concluded that patients and providers felt that telemedicine is feasible and, in some cases, preferred. Though this is a pragmatic representation of the use of telehealth in primary care we identified 2 significant limitations. The first was the small number of patients with LBP. The initial N was 100, but only 8 were seeking care for LBP. The second was an inability to discern what type of low back pain evaluation was completed. The article adds to the body of literature surrounding telehealth in general but does little to specify its use or effectiveness in the treatment of low back pain [29].

4. Discussion

4.1. Excluded studies and limitations

The goal of this systematic review was to identify all clinical trials and cohort studies that utilized some type of synchronous telehealth intervention for the virtual management of low back pain. After an extensive search and evaluation of the existing literature we only found a single unblinded, non-inferiority trial comparing a synchronous telehealth interaction with standard, in-person care [23]. The trial design was a prospective cohort that used a convenience sample in which the findings indicated that telehealth assessment and interventions were “not inferior” to in-person physiotherapy for back pain. An additional finding indicated that consumers, in terms of cost and convenience, have higher satisfactions rates with telehealth than face-to-face interactions.

The use of telehealth in the assessment and treatment of low back pain is evolving and accelerating. As physical therapists and chiropractors are becoming the preferred clinicians to manage back pain [30,31], access to these clinicians early and often has been shown to reduce cost and disability while improving patient reported outcomes [[32], [33], [34]]. The studies found in this review reinforce the existing literature indicating that physical therapists can perform comparable evaluations and interventions during in-person interactions and synchronous telehealth environments. This adds to the existing evidence that telehealth assessment and intervention may be one of the solutions to address the growing problem of back pain.

The studies varied widely in their risk of bias levels ( Table.2 ). The strongest studies were Peterson et al. followed by Palacin-Marin et al. Peterson scored a 24/24 indicating little to no risk of bias. Palacin-Marin et al. scored 22/24, losing two points for not having a prospective power calculation of sample size. Cottrell et al., the only study that compared an intervention, scored 22/24, losing points for not having a prospective power calculation of study size. The score received by Truder et al., 17/24, indicated moderate risk of bias in the study. The endpoints were unblinded, the follow up period was not defined, and patients lost to follow up were not discussed. The weakest of the studies was Varkey et al. scoring 7/16 on the MINORS scale, indicating this study had a high risk of bias. The authors did not clearly define the study endpoint, data was collected retrospectively, there was no end of study assessment and there was no prospective power calculation of sample size.

Table 2.

MINORS risk of bias assessment.

| Clearly stated aim | Inclusion of consecutive patients | Prospective data collection | Endpoint is appropriate to study aim | Unbiased assessment of study endpoint | Follow up period appropriate for study aim | <5% loss to follow up | Prospective calculation of study size | Adequate control group | Contemporary groups | Baseline equivalence of groups | Adequate statistical analysis | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cottrell et al., 2019 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| Palacin-Marin et al., 2013 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| Peterson et al., 2019 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 24 |

| Truter et al., 2013 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 |

| Varkey et al., 2008 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | – | – | – | – | 7 |

We identified several limitations associated with the included studies: The sample size was critically small for most of these studies, ranging from 8 patients to 47 patients. In addition to the size of the sample, 3 of the 4 studies did not calculate sample size prior to study initiation. As these were observational trials and there was no specific head-to-head comparison, there were no effect size calculations. Unfortunately, the small sample sizes would diminish any measured effect of a telerehabilitation evaluation, shading the true impact of the evaluation or intervention. Satisfaction was studied, but the focus was on the acceptability of the service to patients. Patients responded very well in terms of convenience and cost. Unfortunately, there was little research into the satisfaction on the clinical side. When, clinicians were included, they were not evaluated with the same metrics. As a critical part of the “evaluation equation,” there is a need for investigations into clinician needs, and the feasibility and acceptability of this type of change.

The most significant limitation to these observational studies was the lack of a systematic approach to the clinical assessment of LBP. Varkey et al. was particularly concerning in that they chose not to specify an evaluation procedure or schema. Additionally, the researchers did not identify the provider performing the initial evaluation. Though this leaves questions regarding comparison, we felt that due to the scarcity of evidence, these omission were not fatal flaws tha required omission of the study. Rather it was right in line as each study used a unique evaluation procedure and focused on the elements the authors deemed necessary to diagnose the source of LBP. This variation is not dissimilar to clinical practice, where there is a wide variety of procedures used to evaluate the spine. As the literature evolves, identifying a core set of measures for an evaluation of LBP may be warranted. Measures for the hip, knee, shoulder and elbow, as well as suggested equipment have previously been studied, [35].

This review has exposed a significant gap in the synchronous telemedicine literature for remote clinical management of LBP, and clearly suggests a need for additional research in this area. To maximize and potentially accelerate a research agenda for telehealth solutions for LBP, an implementation science approach should be considered. This approach would create a targeted research agenda that would allow for faster adoption and dissemination into clinical practice. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is one such approach. The CIFR, proposed by Damschroder et al., in 2009, provides five domains that would serve as a foundation for execution and implementation [36]. These 5 domains are: 1) Intervention characteristics; 2) Outer setting; 3) Inner setting; 4) Process; and 5) Individuals involved. Using these domains and the available literature, we have outlined a plan for future telehealth research.

Intervention Characteristics: Telehealth, as an evaluation or intervention, is a fluid concept. Interventions classified as “telehealth” can be as simple as a short message service (SMS) or as complex as web-based algorithms to triage and predict admission from the ED to the hospital [37,38]. This speaks to the source of the intervention. A program for LBP intervention is likely to come from an internal stakeholder familiar with the current treatment paradigm. The implementation to telehealth is likely going to be perceived as complex; however, as the studies from this review have shown, equipment as simple as a tablet computer and a webcam can deliver a reliable and effective exam [39]. This adaptability can be studied in remote situations where access is an issue and in situations where safety may be of concern. Adaptability and stakeholders’ positive perceptions of telehealth are attributes that may facilitate the adoption of telehealth. Barriers to adoption, in terms of CIFR constructs, may well be the strength of the existing evidence combined with the complexity involved with the infrastructure surrounding the telehealth delivery mechanisms. Future research must include investigation into the least complex mechanisms for effective delivery. If the implementation of telehealth has even the perception of being more difficult than the status quo, it is likely clinicians will not overcome the barriers with the associated changes.

Outer Setting: Policy incentives and patient satisfaction have the potential to influence the research agenda, when treating spine pain. The studies in our review did address patient satisfaction but only in terms of the evaluation itself. Additional research is needed to assess the impact of outer setting elements include patient needs and the external policy objectives. Our research found that indirect costs, especially the costs of lost work and driving to the clinic, had an impact on patient satisfaction [7,25]. Future research could focus the direct costs and subsequent savings associated with the use of telehealth. Fatoye et al. studied the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a McKenzie telerehabilitation protocol delivered via a self-guided phone-based application. Forty-seven participants were randomized to clinic-based treatments or telehealth-based treatments. The authors found that, even after providing all the participants a phone, there was a total reduction in costs of 16,000 Nigerian naira (USD $44.26) [40]. On the surface this may not seem a significant source of savings. However, when put into the context of the median monthly salary of 339,000 naira (USD $888.18), the cost savings to this consumer is significant [41]. Clearly, cost may act as an outer setting facilitator to implementation. Barriers in the outer setting that may inhibit the adoption of telehealth and may directly affect costs are the governmental regulations which are constantly changing and new policy or payment initiatives that may not take into account the unique requirements of a telehealth delivery mechanism. Future research can assist in overcoming fluid payment initiatives with a comparative analysis of telehealth and “bricks and mortar” delivery mechanisms. A cost analysis could include differences in co-pay structure and alternative payment models such as bundled payments and capitated payments.

Inner Setting: The inner setting encompasses the social architecture, culture and climate that patients, providers and staff experience every day [36]. With the changes brought about by COVID-19 the tolerance for change and the acceptance of new ideas has altered the implementation climate at most organizations. Telehealth, once thought of as inferior to face-to-face interactions, has gained traction and is becoming a viable solution to many of the recent challenges. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently showed a 154% increase in telehealth visits during January–March 2020 when compared to the same time last year [42], while telemedicine provider Teladoc reported a spike in video requests to more than 15,000 per day during the same period [43]. In support of this change, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has encouraged the use of telehealth and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid have expanded the types of telehealth services that are covered. Organizational culture and the implementation climate are 2 important inner setting CFIR constructs that, if optimized, will act as facilitators for the implementation of telehealth interventions. With increased expansion, the need for additional telehealth back pain research can only thrive in this climate. The readiness of organizations to adopt telehealth changes may still act as an inner setting barrier but this can be easily overcome as larger organizations such as HHS and CMS influence the implementation climate.

Characteristics of Individuals: The knowledge and beliefs of individuals as well as personal attributes can frame an individual's readiness to change. Regarding telehealth, there appears to be interest in changing behavior, from both providers and patients. Gilbert et al. [44] completed a systematic review of the qualitative methodology surrounding videoconferencing in an orthopedic setting. They found variation in the methodology, similar to the studies cited in this review. One of the common themes found across the studies was convenience. Many patients noted that remote access was more convenient because it contributed to decreased cost and saved time. What was more interesting was the patients' perceptions of the behavior of the therapists. Patients noted that “characteristics such as staring at the screen (rather than moving gaze from camera to screen), listening without interruption, and individually tailoring exercises to patients individual needs facilitated relationship building.” [44] These attributes will likely need to be learned and further researched as it appears there may be different verbal and non-verbal cues that are important in telehealth interactions. Future research should focus on the qualitative aspects of the perceived barriers and facilitators that an individual might pose to telehealth implementation.

Process: The process domains of the CFIR involve the planning, engagement, and execution of the implementation process. These processes are more likely to involve clinician opinion leaders and implementation champions than patients. Furthermore, the process domains of the CFIR are likely to be ongoing rather than onetime events. The ability to sustain this process can act as both a barrier and a facilitator and directly influence the success or failure of an initiative. Early research into process domains has surrounded the formal training of those in the organization responsible for coordinating the implementation process. Sugavanam et al. [45] conducted a two-stage observational cohort implementation study to evaluate the effects of an online training program for clinicians. The implementation study was a follow up to the BeST trial which studied the effects of a cognitive behavioral approach for LBP [45]. Those therapists who integrated the new evidence into practice reported acceptance of the system by both clinicians and patients. They did however identify internal and external barriers that included staffing, capacity and time that prevented rapid uptake of the guidelines. The second stage of the study required implementation of the intervention and a follow-up survey of patients. The authors found that most patients (77%) reported at improvement after the cognitive behavioral intervention. Patient perception of recovery at the 12-month follow-up, a medium effect size was observed for pain in the BeST trial [0.58 (0.48–0.68)] whereas in the current study, a small effect was observed [0.34 (0.23–0.45)] [45]. These findings provide insight into possible future research, including changes in staffing and the capacity of the individual and the organization for sustainable change.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review sought to identify all clinical trials and cohort studies that utilized some type of synchronous telehealth intervention for the virtual management of low back pain. Our search revealed a single unblinded, non-inferiority trial comparing a synchronous telehealth interaction with standard, in-person care [23]. The huge literature gap and lack of clinical trials studying synchronous telehealth interventions for LBP was unexpected. The field of LBP is in dire need of a solution to increase access points for care and faster referral of patients to a non-surgical provider. There are conditions for which management via telehealth has begun to thrive, and we hypothesized that LBP was no different. Unfortunately, this focused area of research is still in its infancy.

We continue to see a rise in spinal complaints year to year [46,47] and costs continue to escalate without subsequent improvements in patient-related outcomes. The key drivers of cost of care in LBP are unnecessary referral for imaging (x-ray, MRI, and CT), opioids, spinal injections, and inappropriate surgical referrals. Research into telehealth triage mechanisms, remote evaluation of patients using a core set of measures and choosing and implementing interventions from a remote location would serve as a foundation for future clinical trials. As researchers examine the issues of acceptability, feasibility, and validity, we can begin to compare costs between on-site and off-site services and the value that these services provide to the healthcare system at large. Telehealth services that facilitate non-pharmacologic care, which is largely under-utilized, present an opportunity if implementation can overcome the challenges of remote delivery (lack of hands on evaluation and treatment). Most value-based care in chronic musculoskeletal conditions requires diligent self-care principles, which are very amenable to telehealth. Thus, some combination of in-person and telehealth would be worthy of study.

Appendix A. Systematic Review Search Strategies

All searches run September 17, 2020.

Ovid Medline

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Back Pain/or exp Back Injuries/or exp sciatic neuropathy/or exp Spinal Diseases/or spinal fusion/or (arachnoiditis or backache* or coccydynia or discitis or dorsalgia or lumbago or postlaminectomy or sciatica or spinal stenosis or spondylarth* or spondylisthesis or spondylo* or ((disc* or disk*) adj (degeneration* or herniation* or prolapse*))).ti,ab,kw. | 203492 |

| 2 | exp Back/or (back or coccyx or facet joint* or intervertebral disc or lumbar or lumbo sacral* or lumbosacral* or spine or spinal or zygapophyseal joint*).ti,ab,kw. | 586571 |

| 3 | exp Pain/or (injur* or pain or pains or painful).ti,ab,kw. | 1570976 |

| 4 | 1 or (2 and 3) | 324285 |

| 5 | exp Telemedicine/or telecommunications/or exp Computer Communication Networks/or decision making, computer-assisted/or user computer interface/or exp Videoconferencing/or (digital care or digital treatment* or e coach or e health or information communication technolog* or information technolog* or internet quer* or m health or mhealth or mobile health or patient internet portal* or remote visit* or short message service or tele care* or tele coach* or tele conference* or tele consult* or tele diagnosis or tele health* or tele home* or tele management or tele med* or tele mentor* or tele monitor* or tele nurs* or tele rehab* or tele screen* or tele support or tele therap* or telecare* or telecoach* or teleconference* or teleconsult* or telediagnosis or telehealth* or telehome* or telemanagement or telematic* or telemed* or telementor* or telemonitor* or telenurs* or telerehab* or telerehabilitation or telescreen* or telesupport or teletherap* or video conferenc* or video rehab* or virtual reality or "Doctor on Demand" or "Livehealth Online" or Amwell or Blue jeans or Chiron health or Doxy or "Go to meeting" or "Go to webinar" or Google hangout* or Google meeting* or Healthtap or Icliniq or Mdlive or Memd or Microsoft teams or Plushcare or Skype or Teladoc or Virtuwell or Vsee or Vtconnec or Zoom).ti,ab,kw. | 187881 |

| 6 | ((app or computer based or internet or mobile or mobile or on line or online or phone or remote or tele* or video or virtual or web*) adj5 (assess* or care or coach* or communication or consult* or forum* or intervention* or monitor* or rehab* or specialist or therap* or train* or treatment* or visit*)).ti,ab,kw. | 103594 |

| 7 | 5 or 6 | 255639 |

| 8 | 4 and 7 | 1956 |

EMBASE via Embase.com

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 'backache'/exp OR ′spine injury'/exp OR ′sciatic neuropathy'/exp OR ′spine disease'/exp OR ′spine fusion'/de | 348,272 |

| 2 | arachnoiditis:ti,ab,kw OR backache*:ti,ab,kw OR coccydynia:ti,ab,kw OR discitis:ti,ab,kw OR dorsalgia:ti,ab,kw OR lumbago:ti,ab,kw OR postlaminectomy:ti,ab,kw OR sciatica:ti,ab,kw OR ′spinal stenosis':ti,ab,kw OR spondylarth*:ti,ab,kw OR spondylisthesis:ti,ab,kw OR spondylo*:ti,ab,kw | 57744 |

| 3 | ((disc* or disk*) NEAR/1 (degeneration* or herniation* or prolapse*)):ti,ab,kw | 19457 |

| 4 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 | 361051 |

| 5 | 'back'/exp OR ′lumbar region'/exp OR ′lumbosacral region'/exp OR 'back'/exp | 226782 |

| 6 | back:ti,ab,kw OR coccyx:ti,ab,kw OR ′facet joint*':ti,ab,kw OR ′intervertebral disc':ti,ab,kw OR lumbar:ti,ab,kw OR ′lumbo sacral*':ti,ab,kw OR lumbosacral*:ti,ab,kw OR spine:ti,ab,kw OR spinal:ti,ab,kw OR ′zygapophyseal joint*':ti,ab,kw | 788915 |

| 7 | #5 OR #6 | 851031 |

| 8 | 'pain'/exp | 1357148 |

| 9 | injur*:ti,ab,kw OR pain:ti,ab,kw OR pains:ti,ab,kw OR painful:ti,ab,kw | 2013891 |

| 10 | #8 OR #9 | 2655033 |

| 11 | #4 OR (#7 AND #10) | 530684 |

| 12 | 'telemedicine'/exp OR 'telecommunication'/de OR 'telehealth'/exp OR 'teleconference'/exp OR ′computer network'/exp OR ′computer interface'/exp OR 'videoconferencing'/exp | 117474 |

| 13 | 'digital care':ti,ab,kw OR ′digital treatment*':ti,ab,kw OR ′e coach':ti,ab,kw OR ′e health':ti,ab,kw OR ′information communication technolog*':ti,ab,kw OR ′information technolog*':ti,ab,kw OR ′internet quer*':ti,ab,kw OR ′m health':ti,ab,kw OR mhealth:ti,ab,kw OR ′mobile health':ti,ab,kw OR ′patient internet portal*':ti,ab,kw OR ′remote visit*':ti,ab,kw OR ′short message service':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele care*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele coach*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele conference*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele consult*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele diagnosis':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele health*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele home*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele management':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele med*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele mentor*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele monitor*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele nurs*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele rehab*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele screen*':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele support':ti,ab,kw OR ′tele therap*':ti,ab,kw OR telecare*:ti,ab,kw OR telecoach*:ti,ab,kw OR teleconference*:ti,ab,kw OR teleconsult*:ti,ab,kw OR telediagnosis:ti,ab,kw OR telehealth*:ti,ab,kw OR telehome*:ti,ab,kw OR telemanagement:ti,ab,kw OR telematic*:ti,ab,kw OR telemed*:ti,ab,kw OR telementor*:ti,ab,kw OR telemonitor*:ti,ab,kw OR telenurs*:ti,ab,kw OR telerehab*:ti,ab,kw OR telerehabilitation:ti,ab,kw OR telescreen*:ti,ab,kw OR telesupport:ti,ab,kw OR teletherap*:ti,ab,kw OR ′video conferenc*':ti,ab,kw OR ′video rehab*':ti,ab,kw OR ′virtual reality':ti,ab,kw OR ′doctor on demand':ti,ab,kw OR ′livehealth online':ti,ab,kw OR amwell:ti,ab,kw OR ′blue jeans':ti,ab,kw OR ′chiron health':ti,ab,kw OR doxy:ti,ab,kw OR ′go to meeting':ti,ab,kw OR ′go to webinar':ti,ab,kw OR ′google hangout*':ti,ab,kw OR ′google meeting*':ti,ab,kw OR healthtap:ti,ab,kw OR icliniq:ti,ab,kw OR mdlive:ti,ab,kw OR memd:ti,ab,kw OR ′microsoft teams':ti,ab,kw OR plushcare:ti,ab,kw OR skype:ti,ab,kw OR teladoc:ti,ab,kw OR virtuwell:ti,ab,kw OR vsee:ti,ab,kw OR vtconnec:ti,ab,kw OR zoom:ti,ab,kw | 77278 |

| 14 | ((app OR ′computer based' OR internet OR mobile OR mobile OR ′on line' OR online OR phone OR remote OR tele* OR video OR virtual OR web*) NEAR/5 (assess* OR care OR coach* OR communication OR consult* OR forum* OR intervention* OR monitor* OR rehab* OR specialist OR therap* OR train* OR treatment* OR visit*)):ti,ab,kw | 151904 |

| 15 | #12 OR #13 OR #14 | 278352 |

| 16 | #11 AND #15 | 3429 |

| Duplicates removed = 1300 | 2129 | |

| NOT Conference Abstracts | 945 | |

| Conference Abstracts | 1184 |

EBSCO CINAHL

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (MH "Back Pain+") or (MH "Back Injuries+") or (MH "Sciatica") or (MH "Spinal Diseases+") or (MH "Spinal Fusion") | 73,866 |

| 2 | TI (arachnoiditis or backache* or coccydynia or discitis or dorsalgia or lumbago or postlaminectomy or sciatica or "spinal stenosis" or spondylarth* or spondylisthesis or spondylo*) OR AB (arachnoiditis or backache* or coccydynia or discitis or dorsalgia or lumbago or postlaminectomy or sciatica or "spinal stenosis" or spondylarth* or spondylisthesis or spondylo*) OR SU (arachnoiditis or backache* or coccydynia or discitis or dorsalgia or lumbago or postlaminectomy or sciatica or "spinal stenosis" or spondylarth* or spondylisthesis or spondylo*) | 13,647 |

| 3 | TI ((disc* or disk*) N1 (degeneration* or herniation* or prolapse*)) OR AB ((disc* or disk*) N1 (degeneration* or herniation* or prolapse*)) OR SU ((disc* or disk*) N1 (degeneration* or herniation* or prolapse*)) | 4517 |

| 4 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 | 77,705 |

| 5 | (MH "Back") | 3660 |

| 6 | TI (back or coccyx or “facet joint*” or “intervertebral disc” or lumbar or “lumbo sacral*” or lumbosacral* or spine or spinal or “zygapophyseal joint*”) OR AB (back or coccyx or “facet joint*” or “intervertebral disc” or lumbar or “lumbo sacral*” or lumbosacral* or spine or spinal or “zygapophyseal joint*”) OR SU (back or coccyx or “facet joint*” or “intervertebral disc” or lumbar or “lumbo sacral*” or lumbosacral* or spine or spinal or “zygapophyseal joint*”) | 187,669 |

| 7 | S5 OR S6 | 187,669 |

| 8 | (MH "Pain+") | 204,983 |

| 9 | TI (injur* or pain or pains or painful) OR AB (injur* or pain or pains or painful) OR SU (injur* or pain or pains or painful) | 597,804 |

| 10 | S8 OR S9 | 617,327 |

| 11 | S4 or (S7 AND S10) | 126,560 |

| 12 | (MH "Telemedicine+") OR (MH "Telenursing") OR (MH "Telepsychiatry") OR (MH "Telehealth") OR (MH "Videoconferencing+") OR (MH "Telecommunications") OR (MH "Teleconferencing") OR (MH "Computer Communication Networks+") OR (MH "Decision Making, Computer Assisted") OR (MH "User-Computer Interface") | 189,923 |

| 13 | TI ("digital care" or "digital treatment*" or "e coach" or "e health" or "information communication technolog*" or "information technolog*" or "internet quer*" or "m health" or mhealth or "mobile health" or "patient internet portal*" or "remote visit*" or "short message service" or "tele care*" or "tele coach*" or "tele conference*" or "tele consult*" or "tele diagnosis" or "tele health*" or "tele home*" or "tele management" or "tele med*" or "tele mentor*" or "tele monitor*" or "tele nurs*" or "tele rehab*" or "tele screen*" or "tele support" or "tele therap*" or telecare* or telecoach* or teleconference* or teleconsult* or telediagnosis or telehealth* or telehome* or telemanagement or telematic* or telemed* or telementor* or telemonitor* or telenurs* or telerehab* or telerehabilitation or telescreen* or telesupport or teletherap* or "video conferenc*" or "video rehab*" or "virtual reality" or "Doctor on Demand" or "Livehealth Online" or Amwell or "Blue jeans" or "Chiron health" or Doxy or "Go to meeting" or "Go to webinar" or "Google hangout*" or "Google meeting*" or Healthtap or Icliniq or Mdlive or Memd or "Microsoft teams" or Plushcare or Skype or Teladoc or Virtuwell or Vsee or Vtconnec or Zoom) OR AB ("digital care" or "digital treatment*" or "e coach" or "e health" or "information communication technolog*" or "information technolog*" or "internet quer*" or "m health" or mhealth or "mobile health" or "patient internet portal*" or "remote visit*" or "short message service" or "tele care*" or "tele coach*" or "tele conference*" or "tele consult*" or "tele diagnosis" or "tele health*" or "tele home*" or "tele management" or "tele med*" or "tele mentor*" or "tele monitor*" or "tele nurs*" or "tele rehab*" or "tele screen*" or "tele support" or "tele therap*" or telecare* or telecoach* or teleconference* or teleconsult* or telediagnosis or telehealth* or telehome* or telemanagement or telematic* or telemed* or telementor* or telemonitor* or telenurs* or telerehab* or telerehabilitation or telescreen* or telesupport or teletherap* or "video conferenc*" or "video rehab*" or "virtual reality" or "Doctor on Demand" or "Livehealth Online" or Amwell or "Blue jeans" or "Chiron health" or Doxy or "Go to meeting" or "Go to webinar" or "Google hangout*" or "Google meeting*" or Healthtap or Icliniq or Mdlive or Memd or "Microsoft teams" or Plushcare or Skype or Teladoc or Virtuwell or Vsee or Vtconnec or Zoom) OR SU ("digital care" or "digital treatment*" or "e coach" or "e health" or "information communication technolog*" or "information technolog*" or "internet quer*" or "m health" or mhealth or "mobile health" or "patient internet portal*" or "remote visit*" or "short message service" or "tele care*" or "tele coach*" or "tele conference*" or "tele consult*" or "tele diagnosis" or "tele health*" or "tele home*" or "tele management" or "tele med*" or "tele mentor*" or "tele monitor*" or "tele nurs*" or "tele rehab*" or "tele screen*" or "tele support" or "tele therap*" or telecare* or telecoach* or teleconference* or teleconsult* or telediagnosis or telehealth* or telehome* or telemanagement or telematic* or telemed* or telementor* or telemonitor* or telenurs* or telerehab* or telerehabilitation or telescreen* or telesupport or teletherap* or "video conferenc*" or "video rehab*" or "virtual reality" or "Doctor on Demand" or "Livehealth Online" or Amwell or "Blue jeans" or "Chiron health" or Doxy or "Go to meeting" or "Go to webinar" or "Google hangout*" or "Google meeting*" or Healthtap or Icliniq or Mdlive or Memd or "Microsoft teams" or Plushcare or Skype or Teladoc or Virtuwell or Vsee or Vtconnec or Zoom) | 58,640 |

| 14 | TI ((app or computer or internet or mobile or mobile or online or phone or remote or tele* or video or virtual or web*) N5 (assess* or care or coach* or communication or consult* or forum* or intervention* or monitor* or rehab* or specialist or therap* or train* or treatment* or visit*)) OR AB ((app or computer or internet or mobile or mobile or online or phone or remote or tele* or video or virtual or web*) N5 (assess* or care or coach* or communication or consult* or forum* or intervention* or monitor* or rehab* or specialist or therap* or train* or treatment* or visit*)) OR SU ((app or computer or internet or mobile or mobile or online or phone or remote or tele* or video or virtual or web*) N5 (assess* or care or coach* or communication or consult* or forum* or intervention* or monitor* or rehab* or specialist or therap* or train* or treatment* or visit*)) | 71689 |

| 15 | S12 OR S13 OR S14 | 260568 |

| 16 | S11 AND S15 | 2129 |

Wiley Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

| ID | Search | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Back Pain] explode all trees | 4880 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Back Injuries] explode all trees | 865 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Sciatic Neuropathy] explode all trees | 319 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Spinal Diseases] explode all trees | 4090 |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor: [Spinal Fusion] this term only | 933 |

| #6 | (arachnoiditis OR backache* OR coccydynia OR discitis OR dorsalgia OR lumbago OR postlaminectomy OR sciatica OR "spinal stenosis" OR spondylarth* OR spondylisthesis OR spondylo*):ti,ab,kw | 8268 |

| #7 | ((disc* or disk*) NEAR/1 (degeneration* or herniation* or prolapse*)):ti,ab,kw | 2118 |

| #8 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 | 17001 |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Back] explode all trees | 686 |

| #10 | ("low back" OR coccyx OR "facet joint*" OR "intervertebral disc" OR lumbar OR "lumbo sacral*" OR lumbosacral* OR spine OR spinal OR "zygapophyseal joint*"):ti,ab,kw | 48350 |

| #11 | #9 OR #10 | 48495 |

| #12 | MeSH descriptor: [Pain] explode all trees | 48748 |

| #13 | (injur* or pain or pains or painful):ti,ab,kw | 225318 |

| #14 | #12 OR #13 | 231230 |

| #15 | #11 AND #14 | 28284 |

| #16 | #8 OR #15 | 36433 |

| #17 | MeSH descriptor: [Telemedicine] explode all trees | 2488 |

| #18 | MeSH descriptor: [Telecommunications] this term only | 86 |

| #19 | MeSH descriptor: [Computer Communication Networks] explode all trees | 3989 |

| #20 | MeSH descriptor: [Decision Making, Computer-Assisted] this term only | 131 |

| #21 | MeSH descriptor: [User-Computer Interface] this term only | 1230 |

| #22 | MeSH descriptor: [Videoconferencing] explode all trees | 203 |

| #23 | ("digital care" OR "digital treatment*" OR "e coach" OR "e health" OR "information communication technolog*" OR "information technolog*" OR "internet quer*" OR "m health" OR mhealth OR "mobile health" OR "patient internet portal*" OR "remote visit*" OR "short message service" OR "tele care*" OR "tele coach*" OR "tele conference*" OR "tele consult*" OR "tele diagnosis" OR "tele health*" OR "tele home*" OR "tele management" OR "tele med*" OR "tele mentor*" OR "tele monitor*" OR "tele nurs*" OR "tele rehab*" OR "tele screen*" OR "tele support" OR "tele therap*" OR telecare* OR telecoach* OR teleconference* OR teleconsult* OR telediagnosis OR telehealth* OR telehome* OR telemanagement OR telematic* OR telemed* OR telementor* OR telemonitor* OR telenurs* OR telerehab* OR telerehabilitation OR telescreen* OR telesupport OR teletherap* OR "video conferenc*" OR "video rehab*" OR "virtual reality" OR "Doctor on Demand" OR "Livehealth Online" OR Amwell OR "Blue jeans" OR "Chiron health" OR Doxy OR "Go to meeting" OR "Go to webinar" OR "Google hangout*" OR "Google meeting*" OR Healthtap OR Icliniq OR Mdlive OR Memd OR "Microsoft teams" OR Plushcare OR Skype OR Teladoc OR Virtuwell OR Vsee OR Vtconnec OR Zoom):ti,ab,kw | 13497 |

| #24 | (((app or "computer based" or internet or mobile or mobile or "on line" or online or phone or remote or tele* or video or virtual or web*) NEAR/5 (assess* or care or coach* or communication or consult* or forum* or intervention* or monitor* or rehab* or specialist or therap* or train* or treatment* or visit*))):ti,ab,kw | 57679 |

| #25 | #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 | 64418 |

| #26 | #16 AND #25 | 1067 |

| Systematic Reviews | 29 | |

| Trials | 1037 | |

| Protocols | 1 |

*updated back in keyword search to “low back” because back appears often in full text.

PEDro

| 1 | Abstract and Title: Remote | 6 |

| Problem: pain | ||

| Body Part: lumbar spine, sacro-iliac joint or pelvis | ||

| 2 | Abstract and Title: Tele* | 38 |

| Problem: pain | ||

| Body Part: lumbar spine, sacro-iliac joint or pelvis | ||

| 3 | Abstract and Title: Video* | 23 |

| Problem: pain | ||

| Body Part: lumbar spine, sacro-iliac joint or pelvis | ||

| 4 | Abstract and Title: Online* | 22 |

| Problem: pain | ||

| Body Part: lumbar spine, sacro-iliac joint or pelvis | ||

| 5 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 | 84 |

Index of Chiropractic Literature

| Query | Items found |

|---|---|

| Subject:\"Back\" OR All Fields:back OR All Fields:lumbar OR All Fields:lumbosacral* OR All Fields:spine OR All Fields:spinal OR All Fields:\"lumbo sacral*\", Peer Review only | 4448 |

| Subject:\"Acute Pain\" OR All Fields:pain OR All Fields:pains OR All Fields:painful OR All Fields:injur*, Peer Review only | 4362 |

| Subject:\"Back\" OR All Fields:back OR All Fields:lumbar OR All Fields:lumbosacral* OR All Fields:spine OR All Fields:spinal OR All Fields:\"lumbo sacral*\", Peer Review only AND Subject:\"Acute Pain\" OR All Fields:pain OR All Fields:pains OR All Fields:painful OR All Fields:injur*, Peer Review only | 2692 |

| Subject:\"Back Pain\" OR Subject:\"Back Injuries\" OR Subject:\"Spinal Diseases\" OR Subject:Spinal Fusion\" OR All Fields:arachnoiditis OR backache* OR coccydynia OR discitis OR dorsalgia OR lumbago OR postlaminectomy OR sciatica OR \"spinal stenosis\" OR spondylarth* OR spondylisthesis OR spondylo*, Peer Review only | 953 |

| Subject:\"Back\" OR All Fields:back OR All Fields:lumbar OR All Fields:lumbosacral* OR All Fields:spine OR All Fields:spinal OR All Fields:\"lumbo sacral*\", Peer Review only AND Subject:\"Acute Pain\" OR All Fields:pain OR All Fields:pains OR All Fields:painful OR All Fields:injur*, Peer Review only OR Subject:\"Back Pain\" OR Subject:\"Back Injuries\" OR Subject:\"Spinal Diseases\" OR Subject:Spinal Fusion\" OR All Fields:arachnoiditis OR backache* OR coccydynia OR discitis OR dorsalgia OR lumbago OR postlaminectomy OR sciatica OR \"spinal stenosis\" OR spondylarth* OR spondylisthesis OR spondylo*, Peer Review only | 2754 |

| Subject:\"telemedicine\" OR Subject:\"Computer Communication Networks\" OR Subject:\"Computers\" OR All Fields:\"digital care\" OR \"digital treatment*\" OR \"e coach\" OR \"e health\" OR \"information communication technolog*\" OR \"information technolog*\" OR \"internet quer*\" OR \"m health\" OR mhealth OR \"mobile health\" OR \"patient internet portal*\" OR \"remote visit*\" OR \"short message service\" OR \"tele care*\" OR \"tele coach*\" OR \"tele conference*\" OR \"tele consult*\" OR \"tele diagnosis\" OR \"tele health*\" OR \"tele home*\" OR \"tele management\" OR \"tele med*\" OR \"tele mentor*\" OR \"tele monitor*\" OR \"tele nurs*\" OR \"tele rehab*\" OR \"tele screen*\" OR \"tele support\" OR \"tele therap*\" OR telecare* OR telecoach* OR teleconference* OR teleconsult* OR telediagnosis OR telehealth* OR telehome* OR telemanagement OR telematic* OR telemed* OR telementor* OR telemonitor* OR telenurs* OR telerehab* OR telerehabilitation OR telescreen* OR telesupport OR teletherap* OR \"video conferenc*\" OR \"video rehab*\" OR \"virtual reality\" OR \"Doctor on Demand\" OR \"Livehealth Online\" OR Amwell OR \"Blue jeans\" OR \"Chiron health\" OR Doxy OR \"Go to meeting\" OR \"Go to webinar\" OR \"Google hangout*\" OR \"Google meeting*\" OR Healthtap OR Icliniq OR Mdlive OR Memd OR \"Microsoft teams\" OR Plushcare OR Skype OR Teladoc OR Virtuwell OR Vsee OR Vtconnec OR Zoom, Peer Review only | 28 |

| All Fields:tele* OR All Fields:web* OR All Fields:computer* OR All Fields:online* OR All Fields:remote OR All Fields:internet OR All Fields:mobile OR All Fields:virtual OR All Fields:video, Peer Review only | 1011 |

| Subject:\"telemedicine\" OR Subject:\"Computer Communication Networks\" OR Subject:\"Computers\" OR All Fields:\"digital care\" OR \"digital treatment*\" OR \"e coach\" OR \"e health\" OR \"information communication technolog*\" OR \"information technolog*\" OR \"internet quer*\" OR \"m health\" OR mhealth OR \"mobile health\" OR \"patient internet portal*\" OR \"remote visit*\" OR \"short message service\" OR \"tele care*\" OR \"tele coach*\" OR \"tele conference*\" OR \"tele consult*\" OR \"tele diagnosis\" OR \"tele health*\" OR \"tele home*\" OR \"tele management\" OR \"tele med*\" OR \"tele mentor*\" OR \"tele monitor*\" OR \"tele nurs*\" OR \"tele rehab*\" OR \"tele screen*\" OR \"tele support\" OR \"tele therap*\" OR telecare* OR telecoach* OR teleconference* OR teleconsult* OR telediagnosis OR telehealth* OR telehome* OR telemanagement OR telematic* OR telemed* OR telementor* OR telemonitor* OR telenurs* OR telerehab* OR telerehabilitation OR telescreen* OR telesupport OR teletherap* OR \"video conferenc*\" OR \"video rehab*\" OR \"virtual reality\" OR \"Doctor on Demand\" OR \"Livehealth Online\" OR Amwell OR \"Blue jeans\" OR \"Chiron health\" OR Doxy OR \"Go to meeting\" OR \"Go to webinar\" OR \"Google hangout*\" OR \"Google meeting*\" OR Healthtap OR Icliniq OR Mdlive OR Memd OR \"Microsoft teams\" OR Plushcare OR Skype OR Teladoc OR Virtuwell OR Vsee OR Vtconnec OR Zoom, Peer Review only OR All Fields:tele* OR All Fields:web* OR All Fields:computer* OR All Fields:online* OR All Fields:remote OR All Fields:internet OR All Fields:mobile OR All Fields:virtual OR All Fields:video, Peer Review only | 1011 |

| Subject:\"Back\" OR All Fields:back OR All Fields:lumbar OR All Fields:lumbosacral* OR All Fields:spine OR All Fields:spinal OR All Fields:\"lumbo sacral*\", Peer Review only AND Subject:\"Acute Pain\" OR All Fields:pain OR All Fields:pains OR All Fields:painful OR All Fields:injur*, Peer Review only OR Subject:\"Back Pain\" OR Subject:\"Back Injuries\" OR Subject:\"Spinal Diseases\" OR Subject:Spinal Fusion\" OR All Fields:arachnoiditis OR backache* OR coccydynia OR discitis OR dorsalgia OR lumbago OR postlaminectomy OR sciatica OR \"spinal stenosis\" OR spondylarth* OR spondylisthesis OR spondylo*, Peer Review only AND Subject:\"telemedicine\" OR Subject:\"Computer Communication Networks\" OR Subject:\"Computers\" OR All Fields:\"digital care\" OR \"digital treatment*\" OR \"e coach\" OR \"e health\" OR \"information communication technolog*\" OR \"information technolog*\" OR \"internet quer*\" OR \"m health\" OR mhealth OR \"mobile health\" OR \"patient internet portal*\" OR \"remote visit*\" OR \"short message service\" OR \"tele care*\" OR \"tele coach*\" OR \"tele conference*\" OR \"tele consult*\" OR \"tele diagnosis\" OR \"tele health*\" OR \"tele home*\" OR \"tele management\" OR \"tele med*\" OR \"tele mentor*\" OR \"tele monitor*\" OR \"tele nurs*\" OR \"tele rehab*\" OR \"tele screen*\" OR \"tele support\" OR \"tele therap*\" OR telecare* OR telecoach* OR teleconference* OR teleconsult* OR telediagnosis OR telehealth* OR telehome* OR telemanagement OR telematic* OR telemed* OR telementor* OR telemonitor* OR telenurs* OR telerehab* OR telerehabilitation OR telescreen* OR telesupport OR teletherap* OR \"video conferenc*\" OR \"video rehab*\" OR \"virtual reality\" OR \"Doctor on Demand\" OR \"Livehealth Online\" OR Amwell OR \"Blue jeans\" OR \"Chiron health\" OR Doxy OR \"Go to meeting\" OR \"Go to webinar\" OR \"Google hangout*\" OR \"Google meeting*\" OR Healthtap OR Icliniq OR Mdlive OR Memd OR \"Microsoft teams\" OR Plushcare OR Skype OR Teladoc OR Virtuwell OR Vsee OR Vtconnec OR Zoom, Peer Review only OR All Fields:tele* OR All Fields:web* OR All Fields:computer* OR All Fields:online* OR All Fields:remote OR All Fields:internet OR All Fields:mobile OR All Fields:virtual OR All Fields:video, Peer Review only | 279 |

ClinicalTrials.gov

160 Studies found for: telemedicine OR telerehabilitation OR telehealth OR remote OR video OR mobile health OR online OR virtual OR web OR tele OR internet | Low Back Pain.

Appendix B. MINORS Assessment Scale

| Methodological items for non-randomized studies | Score* |

|---|---|

| 1. A clearly stated aim: the question addressed should be precise and relevant in the light of available literature | |

| 2. Inclusion of consecutive patients: all patients potentially fit for inclusion (satisfying the criteria for inclusion) have been included in the study period (no exclusion or details about the reasons for exclusion) | |

| 3. Prospective collection of data: data were collected according to a protocol established before the beginning of the study | |

| 4. Endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study: unambiguous explanation of the criteria used to evaluate the main outcome which should be in accordance with the question addressed by the study. Also, the endpoints should be assessed on an intention-to-treat basis. | |

| 5. Unbiased assessment of the study endpoint: blind evaluation of objective endpoints and double-blind evaluation of subjective endpoints. Otherwise reasons for not blinding should be stated. | |

| 6. Follow-up period appropriate to the aim of the study: the follow-up should be sufficiently long to allow the assessment of the main endpoint and possible adverse events. | |

| 7. Loss to follow up less than 5%: all patients should be included in the follow up. Otherwise, the proportion lost to follow up sholud not exceed the proportion experiencing the major endpoint. | |

| 8. Prospective calculation of the study size: information of the size of detectable difference of interest with a calculation of 95% confidence interval, according to the expected incidence of the outcome event, and onformation about the level for statistical significance and estimates of power when comparing the outcomes. | |

| Additional criteria in case of comparative study | |

| 9. An adequate control group: having a gold standard diagnostic test or therapeutic intervention recognized as the optimal intervention according to the available published data. | |

| 10. Contemporary groups: control and studied group should be managed during the same time period (no historical comparison) | |

| 11. Baseline equivalence of groups: the groups should be similar regarding the criteria other than the studied endpoints. Absence of confounding factors that could bias the interpretation of the results. | |

| 12. Adequate statistical analyses: whether the statistics were in accordance with the type of study witht the calculation of confidence intervals or relative risk. |

*The items are scored 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but inadequate) or 2 (reported and adequate). The global ideal score being 16 for non-comparative studies and 24 for comparative studies.

Appendix C. Clinical Trials Excluded During Full Text Screening

| Study | Sample Size | Study/Intervention | Telehealth Medium | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trialsrowhead | |||||

| Bernardelli et al., 2020 [48] | 47 Control 37 Telehealth | Control: 7 weeks of moderate intensity exercise in a gym at the worksite departments. The aim was to increase muscle strength in the lower back, neck, and shoulders and increase core (abdomen and lower back) stability | Low back booklet supported by a video on the company intranet website. | Primary outcome was the change from baseline to 7-week follow-up in the RMDQ score between the workplace- and home-based groups. Secondary outcomes, included the change in average of functional and psychological assessment. Functional assessment includes RMDQ, FABQ, and Tampa Scale. Psych assessment includes the Psychological General Well Being Index, and the Zung anxiety and depression scales. | The authors found improvement of RMDQ, TSK, and FARQ. TSK showed a slightly higher improvement in the home-based group. The ODI showed improvement in the workplace group and no effect in the home-based one. Small changes in well-being scales were observed, except a decrease of mean Zung D in the home-based group. |

| Intervention: 7 weeks of the same exercises done by the workplace group, adapted to low back pain, planned by a physiotherapist, illustrated in a booklet and in a video available on the company intranet website. | |||||

| Buhurman et al., 2011 [49] | 28 Control 26 Telehealth | Control: A waiting where participants were instructed to monitor their pain intensity daily for two weeks before and two weeks after the treatment period (recorded as a pain diary) | E-mail based support with online print text material and forms. The site was accessible only with a password provided to the participants. | Primary outcome was the catastrophizing subscale of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire. Secondary outcomes included pain, anxiety, depression and QOL. | The authors found statistically significant reductions from pre- to post-treatment in catastrophizing & improvement in quality of life for the treatment group. On a scale measuring pain catastrophizing, 58% (15/26) of the treated participants showed reliable improvement, compared with 18% (5/28) of the control group. |

| Intervention: A self-help management program based on a cognitive behavioral model of chronic pain. The therapist responded to questions, and provided feedback and encouragement on a weekly basis, in association with the completion of treatment modules and homework assignments. Approximately 10–15 min per week was spent on each participant. | All treatment contact with participants was via e-mail. | ||||

| Chhabra et al., 2018 [50] | 48 Control 45 Telehealth | Control: Received a written prescription from the Physician, containing a list of prescribed medicines and dosages, and stating the recommended level of physical activity (including home exercises) | Web-based app developed by the authors (SnapCare). Patients receive daily activity goals (including back and aerobic exercises), tailored to individual health status, ADLs, and daily activity progress. The app attempts to motivate, promote, and guide participants to increase their level of physical activity and exercise adherence | Primary outcomes were pain and disability. | Both groups had a significant improvement in pain and disability (p < 0.05). The App group showed a statistically significantly greater decline in disability (p < 0.001) |

| Intervention: Received the same prescription and instructions as the control and Snapcare, a web-based support app that encouraged increased physical activity. | |||||

| Study | Sample Size | Study/Intervention | Telehealth Medium | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiauzzi et al., 2010 [51] | 104 Control 95 Telehealth | Control: Participants were e-mailed a back pain guide after baseline screening. | painACTION-Back Pain is a website based on CBT and self-management principles. It includes components that help people cope with chronic low back pain: collaborative decision making with health professionals; CBT to improve self-efficacy, manage thoughts and mood, set clinical goals, work on problem-solving life situations, and prevent pain relapses; motivational enhancement through tailored feedback; wellness activities to enhance good sleep, nutrition, stress management, and exercise practices. | Outcomes included: The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS), the Chronic Pain Coping Inventory-42 (CPCI-42, Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ), Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ). | Intervention participants reported significantly: lower stress; increased coping self-statement; greater use of social support. Comparisons between groups suggested clinically significant differences in current pain intensity, depression, anxiety, stress, and global ratings of improvement. Among participants recruited online, those using the Website reported significantly: lower “worst” pain; lower “average” pain; and 3) increased coping self-statements, compared with controls |

| Intervention: Participants were instructed to log onto the painACTION-Back Pain study Website, in their own environment, for two weekly sessions across 4 weeks. Participants were asked to spend at least 20 min in each session. Protocols served as guides to online content to be reviewed, with instructions for the intervention phase (first 4 weeks) as well as the booster phase (five monthly visits during the follow-up period). | |||||

| Cottrell et al., 2019 [23] | 15 Control 46 Telehealth |

Control: Non-surgical management for their back or neck pain within person visits to their local physiotherapy provider. | The eHAB telerehabilitation web-based platform is a clinically validated telehealth system from NEOREHAB. It provides real time video conferencing, advanced media tools including chat platforms and exercise prescription, remote measurement of joint and body position and real time feedback to patients. | Outcomes included the Oswestry Disability Index, the Neck Disability Index, Pain severity using a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS), the Assessment of Quality of Life – 6 Dimensions (AQoL-6D). the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, (PSEQ), the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) | There were no significant group-by-time interactions observed for either pain-related disability (p ¼ 0.706), pain severity (p ¼ 0.187) or health-related quality of life (p ¼ 0.425) measures. The telerehabilitation group reported significantly higher levels of treatment satisfaction (median: 97 vs. 76.5; p ¼ 0.021); |

| Intervention: Participants who chose to undertake their nonsurgical management via telerehabilitation were referred to the Telehealth Clinic. The Telehealth Clinic utilized the eHAB telerehabilitation web-based platform, where patients were able to independently connect with their clinicians on their own Internet enabled computer device from within their home. | |||||

| Pozo-Cruz et al., 2012 [52] | 50 Control 50 Telehealth |

Control: Standard preventive medicine care. Intervention: A short e-mail was sent every day with a reminder message containing a link to the online “session of the day”. The sessions were structured in real-time, first playing a video of postural reminders (2 min), then a video of the exercise(s) for the day (7 min), followed by postural reminders once again (2 min). The videos were available Monday to Friday, weekly, for 9 months. Participants were asked not to perform any formal physical activity routine during the training period. |

Web based email with links to online resources. Each participant was assigned a username and password to access the system, and the treatment program was explained to them. | Primary outcome measures included STarT Back Screening Tool (SBST), Roland Morris score, and European Quality of Life Questionnaire – 5 dimensions – 3 levels. | At 9 months, SBST was analyzed and compared with the baseline and controls. Significant positive effects were found on mean scores recorded in the online occupational exercise intervention group for risk of chronicity (p < 0.019). A correlation between functional disability, health-related quality of life and risk of chronicity of low back pain was observed. |

| Sample Size | Study/Intervention | Telehealth Medium | Outcomes | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priebe et al., 2020 [53] | 312 Control 933 Telehealth | Control: standard of care for the treatment of LBP coordinated by the general practitioner after signing the informed consent. It was considered that the control GPs use the German national guidelines as their “standard of care” | Kaia Health is a multiplatform app for iOS, Android, and native Web solutions. Kaia is available via the App Store (iOS), the Google Play Store, or as a native website. App sign up involves extensive medical screening and a general fitness screen to tailor a specific exercise regimen for each patient. The exercise content features a pool of each different exercises (physiotherapy, mindfulness, and education). Exercises in each of the categories are customized more clearly to the user's feedback. PT exercises are subdivided into 19 different difficulty levels. The exercises are based on the concept of lumbar motor control exercise. | The primary outcome was pain intensity measured on a 11-point numeric ratings scale for the current pain as well as for maximum and average pain over the previous 4 weeks. | The intervention group showed significantly stronger pain reduction compared to the control group after 3 months (IG: M = −33.3% vs CG: M = −14.3%). The Rise-uP group was also superior in | |

| Intervention: The Rise-uP treatment protocol was inspired by the German National Guideline for the treatment of NLBP. Treatment was initiated using the STarT Back screening tool. Risk scoring initiated a teleconsultation with pain specialists was initiated. The patient was supplied with the Kaia App via the Kaia server. | Secondary outcomes included functional ability, psycho pathological and wellbeing parameters as well as pain graduation. The Depression-Anxiety-Stress-Scale (DASS) was applied for measuring psycho pathological symptoms. The Hannover Functional Ability Questionnaire (HFAQ) was used to determine functional ability. The Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey (VR-12) measured mental and physical wellbeing. The Graded Chronic Pain Status GCPS was used for grading pain severity. | secondary outcomes. | ||||

| Krein et al., 2013 [54] | 118 Control 111 Telehealth | Control: Enhanced usual care participants received the uploading pedometer and monthly email reminders to upload their pedometer data. However, they did not receive any goals or feedback and their access to the study website was limited. | Website developed by the authors to upload pedometer data, establish weekly goals, and find graphical and written feedback about their progress toward goals. Informational messages are emailed to participants that included quick tips, which changed every other day, and weekly updates about topics in the news. Back class materials, which included handouts about topics such as body mechanics, use of cold packs, lumbar rolls, and good posture, as well as a video demonstrating specific strengthening and stretching exercises were also available on the website. Finally, the website-based e-community or forum allowed participants to post suggestions, ask questions, and share stories. | Primary outcome measure was Roland Morris Disability Quotient (RDQ). | At 6 months, average RDQ scores were 7.2 for intervention participants compared to 9.2 for usual care, an adjusted difference of 1.6 (95% CI 0.3–2.8, P = 0.02) for the complete case analysis and 1.2 (95% CI -0.09 to 2.5, P = 0.07) for the all case analysis. A post hoc analysis of patients with baseline RDQ scores ≥4 revealed even larger adjusted differences between groups at 6 months but at 12 months the differences were no longer statistically significant. | |