Abstract

Despite the successful identification of causative genes and genetic variants of retinitis pigmentosa (RP), many patients have not been molecularly diagnosed. Our recent study using targeted short-read sequencing showed that the proportion of carriers of pathogenic variants in EYS, the cause of autosomal recessive RP, was unexpectedly high in Japanese patients with unsolved RP. This result suggested that causative genetic variants, which are difficult to detect by short-read sequencing, exist in such patients. Using long-read sequencing technology (Oxford Nanopore), we analysed the whole genomes of 15 patients with RP with one heterozygous pathogenic variant in EYS detected in our previous study along with structural variants (SVs) in EYS and another 88 RP-associated genes. Two large exon-overlapping deletions involving six exons were identified in EYS in two patients with unsolved RP. An analysis of an independent patient set (n=1189) suggested that these two deletions are not founder mutations. Our results suggest that searching for SVs by long-read sequencing in genetically unsolved cases benefits the molecular diagnosis of RP.

Keywords: Sequence Analysis, DNA; Eye Diseases

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP; OMIM:268000) is a prevailing form of inherited retinal dystrophy (IRD) and a major cause of blindness worldwide. RP is inherited in autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-linked inheritance patterns following Mendel’s law of inheritance, with very few exceptions.1 So far, more than 80 genes have been reported as genetic causes of RP. As with other Mendelian disorders,2 3 40%~70% of patients with RP do not have a molecular diagnosis.1 4–6 Nevertheless, advances in sequencing technology have enabled scientists to reveal the genetic causes of RP.1 6–9 Previous studies have demonstrated that EYS, USH2A, RPGR and RHO are the frequent causative genes of RP across ethnicities.1 6 7 For Japanese patients with RP, EYS, which is the cause of autosomal recessive RP (ARRP), has been reported as the most frequent causative gene.6 10

We previously reported the targeted short-read sequencing of 83 RP-associated genes in 1204 Japanese patients with RP.11 In that study, custom-made multiplex PCR-based targeted resequencing was performed using a next-generation sequencer. As a result, causative genes were determined in 29.6% of patients; however, the remaining cases remained unsolved. Importantly, the study indicated that more than a quarter of unsolved patients had one pathogenic variant in EYS,11 suggesting that EYS is a promising candidate as the causative gene.11 Although the exact reason for this observation has not been clarified, it is possible that variants that are difficult to identify by short-read targeted resequencing, such as structural variants (SVs) and intronic variants, are another causative variant. Indeed, SVs, intronic variants and hypomorphic variants have been uncovered as a second pathogenic variant in patients with IRD.9 12–15 Therefore, we considered whether carriers of pathogenic variants in EYS have second causative variants that are not detectable by short-read target sequencing.11

Long-read sequencing technology has several advantages compared with short-read sequencing, such as accurate SV detection.16 17 In order to increase the number of solved patients with RP and to deepen our knowledge about the genetic basis of RP, here we conducted a sequencing study of 15 patients with RP who are carriers of one pathogenic variant in EYS using long-read sequencing and examined the frequencies of the identified SVs from an independent patient group in our previous study (n=1189).11

Materials and methods

Study patients

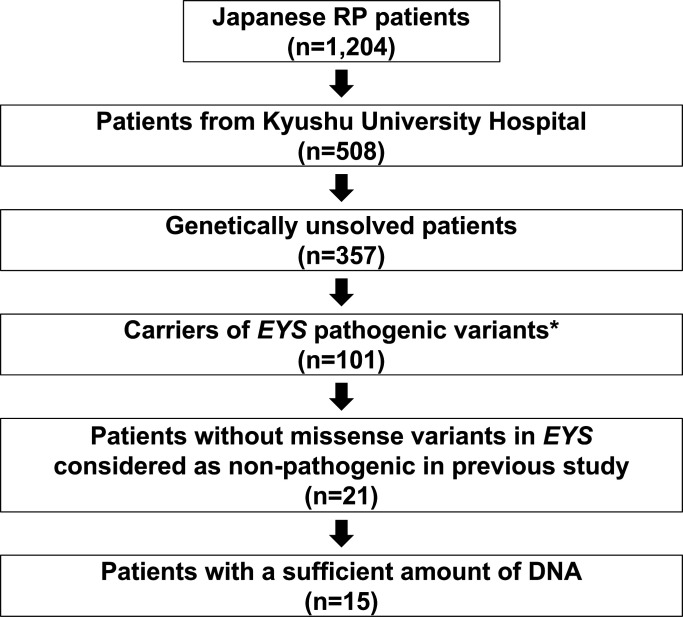

The clinical diagnosis of RP was based on the patient’s history, visual field and electroretinography outcomes, as well as ophthalmological findings by trained ophthalmologists. We selected 15 cases (figure 1) with heterozygous pathogenic variants in EYS from our previous study11 for whole-genome long-read sequencing. To assess founder effects of the identified variants in the Japanese population, we examined the frequencies of the SVs in the independent patient group from our previous study (n=1189).11 For validation purposes, we performed multiplex PCR-based targeted sequencing18 using the independent RP patient set.

Figure 1.

Details of the sample selection. Of the 1204 cases included in the previous study, 508 were patients with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) at Kyushu University Hospital. Among them, we selected 101 genetically unresolved cases with heterozygous pathogenic variants (known pathogenic or loss of function variants) in the EYS gene. Among these cases, 80 cases had missense variants of unknown pathogenic significance in addition to the above-mentioned pathogenic variants. Considering the possible pathogenesis of missense variants not considered pathogenic in our previous study, patients with such variants were excluded. Of the remaining 21 cases, 15 cases with a sufficient amount of DNA were selected for long-read sequencing using the Oxford Nanopore sequencer.

Library preparation and sequencing for whole-genome long-read sequencing

Libraries for long-read sequencing were prepared using the SQK-LSK109 Ligation Sequencing Kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) following the manufacturer’s protocol, and the sequencing itself was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using FLO-MIN106 R9.4.1 flow cells (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) for 96 hours. The number of sequencing runs was adjusted to obtain at least 45 Gb of data for each sample (online supplemental table S1).

jmedgenet-2022-108428supp001.pdf (3.3MB, pdf)

Identification and validation of SVs in RP-associated genes

Base-calling was performed using Guppy V.4.4.1 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). We mapped reads to the reference sequence (GRCh38) and focused on SVs, because long-read sequencing does not have high detection accuracy for single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) or short indels.17 19 We used the CAMPHOR17 pipeline to detect indels (≥50 bp), inversions, duplications and translocations. After the variant-calling, SVs longer than 1 Mb were excluded due to the possibility of variant-calling errors.

To select candidate pathogenic SVs for RP, we analysed EYS and another 88 RP-associated genes listed in the Retinal Information Network (RetNet) (https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/) as of 14 April 2021 (online supplemental table S2). We proceeded to search for the following types of SVs: (1) SVs in the coding region of EYS, which is one of the most promising candidate causative genes, (2) SVs which overlap human retina-specific exons of EYS that may play important roles in retinal diseases,20 (3) SVs within 500 bp of the exon boundaries of EYS that could affect splicing or promoter functions and (4) SVs in the RefSeq coding regions of other RP genes that could be causative variants. Variant classification was performed for the detected variants according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG).21

To prioritise pathogenic SVs, the allele frequencies (AFs) of the SVs were compared with those in our in-house long-read whole-genome sequencing data (53 Japanese healthy control samples), Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD SVs v2.1) and dbVar database.22 We removed variants using the following criteria: (1) variants found in the 53 Japanese control samples, and (2) variants with an AF>0.5% for recessive genes and >0.01% for dominant genes in gnomAD SVs or dbVar.

Among the SVs overlapping the EYS region, we excluded three large SVs (110 Mb inversion, 82 Mb inversion and 97 Mb translocation) to avoid variant-calling errors using the following criteria: (1) the size of the SVs was too large, (2) there were only two reads supporting the breakpoints of the SVs and (3) the 1 kb sequence around the breakpoint was aligned with multiple regions of the human genome and likely to be a repeat region. We noted that the excluded SVs were less likely to be pathogenic, since their breakpoints did not overlap with the regions of RP-associated genes.

We tried to identify SNVs from long-read data and compared the results with our previous study11 (online supplemental table S3). Long-read sequencing identified a much larger number of SNVs than short-read sequencing, suggesting a higher error rate in the former. Therefore, we did not take SNVs into consideration in the current study.

To validate the identified SVs, we amplified the SV junction regions by PCR using KOD Multi&Epi enzyme (TOYOBO), and amplicons were subjected to Sanger sequencing.

To examine the frequencies of the SVs in the independent patient group (n=1189),11 we performed multiplex PCR-based targeted sequencing. Three types of PCR primer sets were designed for each of the identified SVs to amplify the upstream breakpoint regions, downstream breakpoint regions and deleted regions of the large deletions (online supplemental figure 1 and table S4). The details of the sequencing method have been described previously.18

Results

We selected 15 patients with RP with one pathogenic variant in EYS from our previous study11 and confirmed that all of them had typical RP. We performed whole-genome sequencing with the Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencer. The average number of reads and their lengths were 6 623 354.7 and 8136.7 bp, respectively (online supplemental figure 2, table S1), and 93.7% of the reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) (online supplemental table S5). The mean depth of the EYS region was 16.5. The most the EYS region (94.1%) was covered by ≥10 reads (online supplemental figure 3, table S6).

We confirmed that the pathogenic variants of EYS detected in our previous targeted resequencing study11 could be found by long-read sequencing all patients (online supplemental figure 4, table S7). We then focused on identified SVs. In the 15 patients with RP sequenced, 46 899 SVs consisting of 22 786 deletions, 22 790 insertions, 89 inversions, 765 duplications and 469 translocations were identified across the genome. We observed 176 exon-overlapping SVs per patient on average, which included 103 deletions, 44 insertions, 7 inversions, 10 duplications and 12 translocations (online supplemental table S8). Next, we focused on SVs overlapping 89 RP-associated genes and found 15 candidate SVs (table 1). In the ARRP genes, 12 candidate SVs in EYS (9 deletions, 3 insertions), 1 deletion and 1 insertion in RP1L1, and 1 duplication in ARHGEF18 were identified. The three deletions and two insertions in EYS did not overlap with the coding region but were within 500 bp of an exon (table 1). However, no exon-overlapping SVs were detected in autosomal dominant and X-linked recessive RP genes.

Table 1.

Summary of SVs identified in RP-associated genes

| Chr | Start | End | Length (bp) | Type of SV | Gene | Overlap with coding regions of RP-associated genes |

Distance (bp)* | Frequency in in-house data | Frequency in gnomAD | Frequency in dbVar | Sample |

| chr6 | 63 957 115 | 63 958 454 | 1340 | Deletion | EYS | + | – | 14% | – | – | OPH217, OPH517, OPH641, OPH690, OPH861, OPH125, OPH556, OPH595, OPH693 |

| chr6 | 65 001 113 | 65 005 820 | 4708 | Deletion | EYS | + | – | 21% | – | – | OPH125, OPH217, OPH693, OPH556 |

| chr6 | 65 550 144 | 65 552 138 | 1995 | Deletion | EYS | + | – | 81% | – | – | All samples |

| chr6 | 65 689 153 | 65 694 794 | 5642 | Deletion | EYS | + | – | 31% | – | – | OPH125, OPH176, OPH531, OPH556, OPH566, OPH641, OPH693, OPH831, OPH861, OPH332 |

| chr6 | 63 942 754 | 64 337 844 | 395 091 | Deletion | EYS | + | – | – | – | – | OPH861 |

| chr6 | 64 423 168 | 64 798 962 | 375 795 | Deletion | EYS | + | – | – | – | – | OPH641 |

| chr6 | 65 454 074 | 65 454 074 | 305 | Insertion | EYS | + | – | 17% | – | – | OPH217, OPH125, OPH447, OPH517, OPH556, OPH566, OPH690, OPH831, OPH861, OPH693 |

| chr6 | 64 296 539 | 64 296 632 | 94 | Deletion | EYS | – | 66 | – | – | 56% | OPH556, OPH531, OPH517, OPH595, OPH176, OPH641, OPH566, OPH693 |

| chr6 | 65 204 982 | 65 205 044 | 63 | Deletion | EYS | – | 157 | – | 2.4% | – | OPH566, OPH176, OPH690, OPH125 |

| chr6 | 65 564 961 | 65 565 284 | 324 | Deletion | EYS | – | 154 | 80% | – | – | All samples |

| chr6 | 64 295 413 | 64 295 413 | 118 | Insertion | EYS | – | 148 | 27% | – | – | All samples |

| chr6 | 65 278 329 | 65 278 329 | 59 | Insertion | EYS | – | 59 | – | 2.7% | – | All samples |

| chr8 | 10 607 821 | 10 608 503 | 683 | Deletion | RP1L1 | + | – | – | – | – | OPH690 |

| chr8 | 10 610 105 | 10 610 105 | 94 | Insertion | RP1L1 | + | – | 15% | – | – | All samples |

| chr19 | 7 450 130 | 7 451 150 | 1021 | Duplication | ARHGEF18 | + | – | – | – | 7.2% | OPH861, OPH831, OPH693, OPH690, OPH566, OPH556, OPH531, OPH517, OPH595 |

*The shortest distance between the exon boundary and SV breakpoint.

RP, retinitis pigmentosa; SV, structural variant.

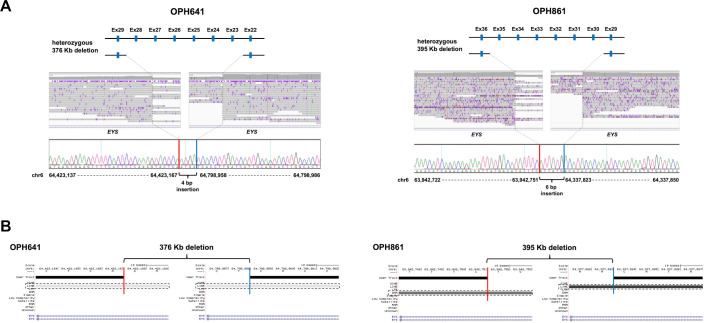

Two large exon-overlapping deletions in EYS were found in OPH641 and OPH861 (figure 2A). The lengths of the identified deletions were approximately 376 kb and 395 kb in OPH641 and OPH861, respectively. We performed Sanger sequencing and detected the exact breakpoint sequences for each SV. One deletion which involved six exons (exon 23–28) was accompanied by a 4 bp insertion within the breakpoints (NM_001142800.1:c.3443+14 421_5927+13 006delinsTCAT; figure 2A). This deleted region fully encompasses and overlaps a region in which an inverted duplication was previously reported.23 Similarly, a 6 bp insertion within the breakpoints was found in the other deletion that overlapped with six exons (exon 30–35) of EYS (NM_001142800.1:c.6079–30740_7055+41 631delinsCATAAT; figure 2A). The breakpoints of both SVs were located in repetitive sequences (figure 2B). Insertions of short fragments were detected at the breakpoints, which suggests that the insertions were caused by fork stalling and template switching (FoSTeS)/microhomology-mediated break-induced replication (MMBIR).24 According to the ACMG guidelines,21 the PVS1 and PM2 criteria were applied to these SVs, and they were considered likely pathogenic. We also confirmed the pathogenicity of SNVs identified in our previous study (Supplementary Note). Considering that two causative variants were present in the ARRP causative gene, we regarded EYS as the causative gene for both OPH641 and OPH861. Clinical information for these two patients is provided in the Supplemental material (online supplemental figure 5). Both probands were sporadic cases according to the medical interviews. Although we were unable to investigate the segregation of the SVs with phenotypes in the pedigrees, this family history is consistent with the ARRP gene (EYS) being the causative gene. For the other thirteen candidate SVs for the ARRP gene, three control data (in-house, gnomAD SVs, dbVar) were used to prioritise variants by AF. A 683 bp heterozygous deletion in RP1L1 found in OPH690 remained, and the other 12 candidates were excluded. According to the ACMG guidelines,21 the PVS1 and PM2 criteria were applied to this SV, and it was considered likely pathogenic. However, the other pathogenic variants in RP1L1 were not detected in OPH690 by our previous targeted resequencing (online supplemental table S9),11 therefore, we did not consider RP1L1 as the causative gene for this patient.

Figure 2.

The causative structural variants (SVs) in EYS. (A) A schematic diagram of heterozygous deletions (top), an integrative genomics viewer (IGV) visualisation of the breakpoints of deletions (middle), and the exact breakpoint sequences confirmed by Sanger sequencing (bottom) in OPH641/OPH861 are shown. In each patient, 4 bp (OPH641)/6 bp (OPH861) insertions were identified within the deletion breakpoints. For example, exon. (B) The genetic elements to which the breakpoints belong to are shown. The downstream breakpoint of the deletion in OPH861 belongs in a repetitive region, and others belong in Long Interspersed Elements (LINE). Red and blue bars display the downstream/upstream breakpoint junctions. The dashed rectangles indicate the genetic elements where the breakpoints are localised.

Finally, we examined the frequencies of the two large SVs in EYS in other patients with RP. We conducted multiplex PCR-based targeted sequencing18 to evaluate these SVs in 1189 independent Japanese patients with RP. However, the two SVs were not detected, suggesting that they are not founder mutations.

Discussion

In this study, we identified likely pathogenic SVs in two previously unsolved RP cases by long-read sequencing. The proportion of patients with a new molecular diagnosis was 2 out of 15, which is consistent with previous reports using short-read whole-genome sequencing (4.8%–12.5%). 23 25

Short-read and long-read sequencing can be applied to whole-genome sequencing. Although the former has the advantage of detecting SNVs and short indels, functional experiments are generally required to assess the causality of intronic variants. On the other hand, long-read sequencing may identify pathogenic SVs, such as exon-overlapping SVs. Indeed, our study identified two likely pathogenic SVs. Although the utility of long-read sequencing for Mendelian diseases is not well established, this study indicates that long-read sequencing contributes to the molecular diagnosis of Mendelian diseases. Our previous and current studies have comprehensively investigated SNVs and short indels in the coding regions and SVs in EYS for 15 cases.11 However, 87% (13/15) of the cases still remain unsolved. Considering that variants in coding regions were well investigated with sufficient coverage (online supplemental table S6), variants in non-coding regions could be the cause for these patients.

This study did not analyse intronic SNVs for three reasons: (1) pathogenic deep intronic EYS variants have not been reported previously, (2) the pathogenicity of intronic variants requires functional validation and (3) long-reads sequencing does not have sufficient accuracy for SNV identification. While long-read sequencing has contributed to molecular diagnosis in some cases, an inadequate search for variants in deep introns may result in the low detection rate of pathogenic variants. Therefore, further evaluation of non-coding regions in patients with unresolved RP by short-read sequencing and functional validation should increase the number of genetically solved patients. Additionally, an analysis of other candidate genes is recommended.

Another limitation of this study is that the haplotypes of the pathogenic variants in the patients could not be examined. A segregation analysis of the patients observed in the present study will further clarify the impact of the identified SVs.

In conclusion, we identified likely pathogenic SVs in an ARRP gene by long-read sequencing. Our results imply that searching for SVs and the comprehensive evaluation of non-coding regions in genetically unsolved cases will contribute to the molecular diagnosis of RP.

Acknowledgments

The super-computing resource was provided by the Human Genome Centre, Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo.

Footnotes

Contributors: MA and AF designed the study. YS performed long-read sequencing. YS, YK and AF analysed the data. YS, MA and AF contributed to data interpretation. ME, TA and Y Momozawa performed Multiplex PCR-based target sequencing. YK, Y Murakami, KF, KH, TN, YW, SU, DG, AM, YH, YI, KMN and KHS collected the samples. YS, JHW, MA and AF contributed to the manuscript preparation and editing. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by AMED under Grant Number JP21km0908001 (A.F.) and by the Japanese Retinitis Pigmentosa Society (M.A.).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

Ethics approval

The ethics committees of Kyushu University Hospital, the University of Tokyo, and all collaborating hospitals have approved this study. All participants have provided written consent to participate in the study. This study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- 1. Verbakel SK, van Huet RAC, Boon CJF, den Hollander AI, Collin RWJ, Klaver CCW, Hoyng CB, Roepman R, Klevering BJ. Non-Syndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res 2018;66:157–86. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG, Bainbridge MN, Willis A, Ward PA, Braxton A, Beuten J, Xia F, Niu Z, Hardison M, Person R, Bekheirnia MR, Leduc MS, Kirby A, Pham P, Scull J, Wang M, Ding Y, Plon SE, Lupski JR, Beaudet AL, Gibbs RA, Eng CM. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of Mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1502–11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1306555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willig LK, Petrikin JE, Smith LD, Saunders CJ, Thiffault I, Miller NA, Soden SE, Cakici JA, Herd SM, Twist G, Noll A, Creed M, Alba PM, Carpenter SL, Clements MA, Fischer RT, Hays JA, Kilbride H, McDonough RJ, Rosterman JL, Tsai SL, Zellmer L, Farrow EG, Kingsmore SF. Whole-genome sequencing for identification of Mendelian disorders in critically ill infants: a retrospective analysis of diagnostic and clinical findings. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:377–87. 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00139-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ge Z, Bowles K, Goetz K, Scholl HPN, Wang F, Wang X, Xu S, Wang K, Wang H, Chen R. NGS-based molecular diagnosis of 105 eyeGENE® probands with retinitis pigmentosa. Sci Rep 2015;5:1–9. 10.1038/srep18287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao L, Wang F, Wang H, Li Y, Alexander S, Wang K, Willoughby CE, Zaneveld JE, Jiang L, Soens ZT, Earle P, Simpson D, Silvestri G, Chen R. Next-Generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of 82 retinitis pigmentosa probands from Northern Ireland. Hum Genet 2015;134:217–30. 10.1007/s00439-014-1512-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oishi M, Oishi A, Gotoh N, Ogino K, Higasa K, Iida K, Makiyama Y, Morooka S, Matsuda F, Yoshimura N. Comprehensive molecular diagnosis of a large cohort of Japanese retinitis pigmentosa and Usher syndrome patients by next-generation sequencing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:7369–75. 10.1167/iovs.14-15458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin-Merida I, Avila-Fernandez A, Del Pozo-Valero M, Blanco-Kelly F, Zurita O, Perez-Carro R, Aguilera-Garcia D, Riveiro-Alvarez R, Arteche A, Trujillo-Tiebas MJ, Tahsin-Swafiri S, Rodriguez-Pinilla E, Lorda-Sanchez I, Garcia-Sandoval B, Corton M, Ayuso C. Genomic landscape of sporadic retinitis pigmentosa: findings from 877 Spanish cases. Ophthalmology 2019;126:1181–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pieras JI, Barragán I, Borrego S, Audo I, González-Del Pozo M, Bernal S, Baiget M, Zeitz C, Bhattacharya SS, Antiñolo G. Copy-Number variations in EYS: a significant event in the appearance of arRP. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:5625–31. 10.1167/iovs.11-7292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zampaglione E, Kinde B, Place EM, Navarro-Gomez D, Maher M, Jamshidi F, Nassiri S, Mazzone JA, Finn C, Schlegel D, Comander J, Pierce EA, Bujakowska KM. Copy-number variation contributes 9% of pathogenicity in the inherited retinal degenerations. Genet Med 2020;22:1079–87. 10.1038/s41436-020-0759-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hosono K, Ishigami C, Takahashi M, Park DH, Hirami Y, Nakanishi H, Ueno S, Yokoi T, Hikoya A, Fujita T, Zhao Y, Nishina S, Shin JP, Kim IT, Yamamoto S, Azuma N, Terasaki H, Sato M, Kondo M, Minoshima S, Hotta Y. Two novel mutations in the EYS gene are possible major causes of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa in the Japanese population. PLoS One 2012;7:e31036. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koyanagi Y, Akiyama M, Nishiguchi KM, Momozawa Y, Kamatani Y, Takata S, Inai C, Iwasaki Y, Kumano M, Murakami Y, Omodaka K, Abe T, Komori S, Gao D, Hirakata T, Kurata K, Hosono K, Ueno S, Hotta Y, Murakami A, Terasaki H, Wada Y, Nakazawa T, Ishibashi T, Ikeda Y, Kubo M, Sonoda K-H. Genetic characteristics of retinitis pigmentosa in 1204 Japanese patients. J Med Genet 2019;56:662–70. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fadaie Z, Whelan L, Ben-Yosef T, Dockery A, Corradi Z, Gilissen C, Haer-Wigman L, Corominas J, Astuti GDN, de Rooij L, van den Born LI, Klaver CCW, Hoyng CB, Wynne N, Duignan ES, Kenna PF, Cremers FPM, Farrar GJ, Roosing S. Whole genome sequencing and in vitro splice assays reveal genetic causes for inherited retinal diseases. NPJ Genom Med 2021;6. 10.1038/s41525-021-00261-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Schil K, Naessens S, Van de Sompele S, Carron M, Aslanidis A, Van Cauwenbergh C, Kathrin Mayer A, Van Heetvelde M, Bauwens M, Verdin H, Coppieters F, Greenberg ME, Yang MG, Karlstetter M, Langmann T, De Preter K, Kohl S, Cherry TJ, Leroy BP, De Baere E, CNV Study Group . Mapping the genomic landscape of inherited retinal disease genes prioritizes genes prone to coding and noncoding copy-number variations. Genet Med 2018;20:202–13. 10.1038/gim.2017.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jespersgaard C, Fang M, Bertelsen M, Dang X, Jensen H, Chen Y, Bech N, Dai L, Rosenberg T, Zhang J, Møller LB, Tümer Z, Brøndum-Nielsen K, Grønskov K. Molecular genetic analysis using targeted NGS analysis of 677 individuals with retinal dystrophy. Sci Rep 2019;9:1–7. 10.1038/s41598-018-38007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ellingford JM, Horn B, Campbell C, Arno G, Barton S, Tate C, Bhaskar S, Sergouniotis PI, Taylor RL, Carss KJ, Raymond LFL, Michaelides M, Ramsden SC, Webster AR, Black GCM. Assessment of the incorporation of CNV surveillance into gene panel next-generation sequencing testing for inherited retinal diseases. J Med Genet 2018;55:114–21. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou A, Lin T, Xing J. Evaluating nanopore sequencing data processing pipelines for structural variation identification. Genome Biol 2019;20:1–13. 10.1186/s13059-019-1858-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujimoto A, Wong JH, Yoshii Y, Akiyama S, Tanaka A, Yagi H, Shigemizu D, Nakagawa H, Mizokami M, Shimada M. Whole-Genome sequencing with long reads reveals complex structure and origin of structural variation in human genetic variations and somatic mutations in cancer. Genome Med 2021;13:1–15. 10.1186/s13073-021-00883-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Momozawa Y, Akiyama M, Kamatani Y, Arakawa S, Yasuda M, Yoshida S, Oshima Y, Mori R, Tanaka K, Mori K, Inoue S, Terasaki H, Yasuma T, Honda S, Miki A, Inoue M, Fujisawa K, Takahashi K, Yasukawa T, Yanagi Y, Kadonosono K, Sonoda K-H, Ishibashi T, Takahashi A, Kubo M. Low-Frequency coding variants in CETP and CFB are associated with susceptibility of exudative age-related macular degeneration in the Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet 2016;25:5027–34. 10.1093/hmg/ddw335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sedlazeck FJ, Lee H, Darby CA, Schatz MC. Piercing the dark matter: bioinformatics of long-range sequencing and mapping. Nat Rev Genet 2018;19:329–46. 10.1038/s41576-018-0003-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farkas MH, Grant GR, White JA, Sousa ME, Consugar MB, Pierce EA. Transcriptome analyses of the human retina identify unprecedented transcript diversity and 3.5 Mb of novel transcribed sequence via significant alternative splicing and novel genes. BMC Genomics 2013;14:486. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lappalainen I, Lopez J, Skipper L, Hefferon T, Spalding JD, Garner J, Chen C, Maguire M, Corbett M, Zhou G, Paschall J, Ananiev V, Flicek P, Church DM, DbVar CDM. DbVar and DGVa: public Archives for genomic structural variation. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:D936–41. 10.1093/nar/gks1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nishiguchi KM, Tearle RG, Liu YP, Oh EC, Miyake N, Benaglio P, Harper S, Koskiniemi-Kuendig H, Venturini G, Sharon D, Koenekoop RK, Nakamura M, Kondo M, Ueno S, Yasuma TR, Beckmann JS, Ikegawa S, Matsumoto N, Terasaki H, Berson EL, Katsanis N, Rivolta C. Whole genome sequencing in patients with retinitis pigmentosa reveals pathogenic DNA structural changes and NEK2 as a new disease gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:16139–44. 10.1073/pnas.1308243110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang F, Khajavi M, Connolly AM, Towne CF, Batish SD, Lupski JR. The DNA replication FoSTeS/MMBIR mechanism can generate genomic, genic and exonic complex rearrangements in humans. Nat Genet 2009;41:849–53. 10.1038/ng.399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carss KJ, Arno G, Erwood M, Stephens J, Sanchis-Juan A, Hull S, Megy K, Grozeva D, Dewhurst E, Malka S, Plagnol V, Penkett C, Stirrups K, Rizzo R, Wright G, Josifova D, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Scott RH, Clement E, Allen L, Armstrong R, Brady AF, Carmichael J, Chitre M, Henderson RHH, Hurst J, MacLaren RE, Murphy E, Paterson J, Rosser E, Thompson DA, Wakeling E, Ouwehand WH, Michaelides M, Moore AT, Webster AR, Raymond FL, NIHR-BioResource Rare Diseases Consortium . Comprehensive rare variant analysis via whole-genome sequencing to determine the molecular pathology of inherited retinal disease. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100:75–90. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jmedgenet-2022-108428supp001.pdf (3.3MB, pdf)